Abstract

To explore the roles of 4-1BB (CD137) and CD28 in corneal transplantation, we examined the effect of 4-1BB/4-1BB ligand (4-1BBL) and/or CD28/CD80/CD86 blockade on corneal allograft survival in mice. Allogeneic corneal transplantation was performed between two strains of wild-type (WT) mice, BALB/c and C57BL/6 (B6), and between BALB/c and B6 WT donors and various gene knockout (KO) recipients. Some of the WT graft recipients were treated intraperitoneally with agonistic anti-4-1BB or blocking anti-4-1BBL monoclonal antibody (mAb) on days 0, 2, 4 and 6 after transplantation. Transplanted eyes were observed over a 13-week period. Allogeneic grafts in control WT B6 and BALB/c mice treated with rat immunoglobulin G showed median survival times (MST) of 12 and 14 days, respectively. Allogeneic grafts in B6 WT recipients treated with anti-4-1BB mAb showed accelerated rejection, with an MST of 8 days. In contrast, allogeneic grafts in BALB/c 4-1BB/CD28 KO and B6 CD80/CD86 KO recipients had significantly prolonged graft survival times (MST, 52·5 days and 36 days, respectively). Treatment of WT recipients with anti-4-1BB mAb resulted in enhanced cellular proliferation in the mixed lymphocyte reaction and increased the numbers of CD4+ CD8+ T cells, and macrophages in the grafts, which correlated with decreased graft survival time, whereas transplant recipients with costimulatory receptor deletion showed longer graft survival times. These results suggest that the absence of receptors for the 4-1BB/4-1BBL and/or CD28/CD80/CD86 costimulatory pathways promotes corneal allograft survival, whereas triggering 4-1BB with an agonistic mAb enhances the rejection of corneal allografts.

Keywords: corneal allograft, T lymphocyte, costimulation, rodent

Introduction

Allogeneic rejection is the most common cause of corneal graft failure, and antigen-specific T-cell activation, which is a critical step in corneal allograft rejection, is the leading cause of corneal graft failure.1,2 Two signals are needed to activate T cells. The first, which gives specificity to the immune response, is provided by the interaction between the alloantigen–major histocompatibility complex expressed on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and the T-cell receptor–CD3 complex expressed on the T cell.3 The second, a costimulatory signal, is mediated through various receptor–ligand pairs. Generally, costimulatory receptors can be classified into the following families: (1) the CD28/inducible costimulator family, (2) the tumour necrosis factor receptor family, to which 4-1BB belongs, and (3) the integrin and immunoglobulin supergene families, which include cell adhesion molecules such as leucocyte function antigen-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1, respectively.

The interaction of CD28 and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) with their APC ligands, CD80/CD86, is one of the dominant costimulatory pathways. The blockade of the pathway has been shown to result in the prevention of allograft rejection in corneal transplantation models.4–7 Although allograft survival is prolonged in many species, induction of tolerance has been more difficult to demonstrate, suggesting that costimulation can be effected by another CD28-independent pathway. In this respect, interaction of 4-1BB (CD137) with the 4-1BB ligand (4-1BBL) on APCs can be a candidate.

4-1BB (CD137) is expressed on activated CD4+ CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and NK T cells. The 4-1BB binds 4-1BB-ligand (4-1BBL) on activated APCs, and provides CD28-independent costimulation of T-cell activation.8–10 Recent studies have shown that expression of 4-1BB is not restricted to subpopulations of lymphoid cells but is distributed across a variety of blood cells. This expression pattern raises the possibility that 4-1BB/4-1BBL interactions may be involved in multiple steps in various innate and adaptive immune responses. The 4-1BB pathway may also be important for allograft rejection because inhibition with an anti-4-1BBL antibody significantly prolongs murine cardiac allograft survival.11

Although the effect of the blockade of these costimulatory signals has been investigated in a number of models, including cardiac, pancreatic islet and skin transplantation models, 4-1BB pathway blockade has never been reported for corneal graft, and therefore such an attempt has been made here. We have used an agonistic anti-4-1BB and blocking anti-4-1BBL monoclonal antibody (mAb) as well as knockout (KO) mice deficient of 4-1BB, CD28, 4-1BB/CD28 or CD80/86 and examined the roles of 4-1BB and CD28 pathway in corneal allograft survival.

Materials and methods

Mice

Inbred adult female WT BALB/c mice (H-2d) and C57BL/6 (B6) mice (H-2b), 8–10 weeks old, were purchased from NCI-Frederick Animal Production Area, Charles River Breeding Laboratory (Frederick, MD). The 4-1BB KO mice were established as previously described12 and backcrossed to BALB/c or B6 backgrounds for more than nine generations. The 4-1BB/CD28 double knockout (DKO) mice were established as previously described13 and backcrossed to BALB/c backgrounds for more than nine generations. CD28 KO and CD80/CD86 DKO mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). The 4-1BB/CD28 DKO mice on B6 background and CD80/CD86 DKO mice on BALB/c mice were not available in our facility. All of the KO mice (4-1BB KO, 4-1BB/CD28 DKO, CD28 KO and CD80/86 DKO) were maintained and bred in a specific pathogen-free facility in Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center animal care facility. Animal studies were conducted in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. A summary of each donor/recipient pair is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of corneal graft survival

| Type of graft | Treatment | Survival (days) | MSTs (days) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c graft in WT B6 | Rat IgG (200 mg) | 9, 10, 10, 10, 12, 14, 15 | 12 | Control |

| BALB/c graft in WT B6 | 3H3 (200 mg) | 6, 7, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8 | 8 | 0·0007*** |

| BALB/c graft in WT B6 | 3H3 (100 mg) | 8, 9, 9, 10, 11, 12 | 9 | 0·065 |

| BALB/c graft in WT B6 | TKS-1 (200 mg) | 10, 11, 11, 12, 12, 13 | 10·5 | 0·095 |

| BALB/c graft in WT B6 | TKS-1 (100 mg) | 8, 8, 11, 12, 12, 15 | 11·5 | 0.413 |

| B6 graft in WT BALB/c | None | 10, 10, 11, 11, 13, 13, 14, 14, 26, 26 | 14 | Control |

| B6 graft in 4-1BBKO BALB/c | None | 13, 19, 23, 42, 76, 91 | 21·5 | 0·0085** |

| B6 graft in CD28KO BALB/c | None | 13, 13, 26, 26, 54, 54, 91, 91 | 40 | 0·047* |

| B6 graft in 4-1BB/CD28KO BALB/c | None | 19, 20, 21, 42, 63, 91, 91 | 52·5 | 0·0001*** |

| BALB/c graft in WT B6 | None | 9, 9, 9, 10, 10, 12, 12, 13, 13, 14, 14, 15 | 12 | Control |

| BALB/c graft in 4-1BBKO B6 | None | 10, 14, 17, 21, 23 | 21 | 0·001** |

| BALB/c graft in CD28KO B6 | None | 10, 15, 21, 23, 32 | 23 | 0·001** |

| BALB/c graft in CD80/86KO B6 | None | 14, 17, 18, 24, 36, 55, 91 | 36 | 0·0001*** |

P-value by the Mantel–Cox log-rank test.

P < 0·05

P < 0·01

P < 0·001.

Orthotopic corneal transplantation

Orthotopic corneal transplantation was performed in the right eye of each animal as previously described.14,15 Briefly, the recipient mouse was anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 3 mg ketamine and 0·0075 mg xylazine. A central 2-mm diameter donor graft was excised and secured in a same-size recipient graft bed with eight interrupted 11-0 nylon sutures (Sharppoint; Vanguard, Houston, TX), after which the anterior chamber was reformed with sterile saline and ofloxacin ointment (Santen Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan). All grafted eyes were examined daily, and grafts with technical difficulties (hyphaema, infection, postoperative cataract, formation of anterior synechiae, or loss of anterior chamber) were excluded from further consideration. In all cases, the sutures were removed on day 7.

Assessment of graft survival

Grafts were evaluated daily by slit lamp biomicroscopy for 13 weeks (91 days). Opacification was scored on a scale of 0–5, as follows: 0, clear graft; 1, minimal superficial non-stromal opacity; 2, minimal deep stromal opacity with pupil margin and iris vessels (iris structure) visible; 3, moderate deep stromal opacity with only the pupil margin visible; 4, intense stromal opacity with the anterior chamber visible; 5, maximal stromal opacity with total obscuration of the anterior chamber. Rejection was defined as a score of 2 or higher at any time from 2 weeks after transplantation to the end of the study. Grafts that displayed transient opacification followed by clearing were not rejected.15,16

Reagents and antibodies

Hybridoma cells producing antibodies to 4-1BB (3H3) and 4-1BBL (TKS-1) were gifts from Dr Robert S. Mittler (Emory University, Atlanta, GA) and Drs H. Yagita and K. Okumura (Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan), respectively. The mAbs were purified from culture supernatant on a protein G column (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). The Fc blocker (2.4G2) was purchased from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA). The following antibodies were purchased from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA): Cyfluorescein (Cy)-Chrome-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 mAb (Clone: GK1.5), Cy-Chrome-conjugated anti-mouse CD8α mAb (Clone: 53-6.7), phycoerythrin (PE) -conjugated anti-mouse CD44 (IM7), PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD11c (HL3), PE-conjugated anti-mouse pan-NK cells (DX5), PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-mouse T-cell receptor-β, fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD11b (M1/70), and PE-conjugated anti-mouse Ly-6G (Gr-1). Anti-mouse interferon-γ (IFN-γ; Clone: R4-6A2) was produced from a hybridoma purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

In vivotreatment with anti-4-1BB or anti-4-1BBL mAb

Recipient mice were treated with i.p. injection of 100 μg or 200 μg of rat anti-mouse 4-1BB or rat anti-mouse 4-1BBL on days 0, 2, 4 and 6 after transplantation. Rat immunoglobulin G (IgG; 200 μg) was given to control recipient mice. Graft rejection was normally noted from day 9 of transplantation. Therefore, mAbs were given until day 6, which is 3 days before the potential rejection.

Isolation and flow cytometry of infiltrating cells in the cornea

To isolate the infiltrating leucocytes, the corneas (4 mm in diameter) were excised aseptically from the limbus, cut into small fragments and incubated with 100 U/ml collagenase type IV (Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7·4 for 60 min at 37° in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The fragments were disrupted by grinding and passage through a cell strainer (70 μm; BD Falcon, Bedford, MA). The cells (5 × 104) were washed with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (Dulbecco's PBS containing 1% fetal bovine saline and 0·1% sodium azide), incubated with an Fc blocker (2.4G2) for 15 min on ice, then stained with the indicated antibodies and analysed by flow cytometry (FACS Calibur; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Mixed lymphocyte reaction

The mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) was performed as previously described17 with some modification. On days 7, 14 and 21 after transplantation (n = 3 at the indicated time-point), mice were killed and draining lymph nodes (DLN) (cervical) were collected. The lymph node cells were passed through a nylon wool column to enrich the T lymphocytes. The responder lymph node cells (2 × 105 cells) from the recipient mice were cultured with X-irradiated (2000 rads) stimulator cells (splenocytes from the naive donor strain) in a final volume of 200 μl at ratios of 2 : 1, 10 : 1 and 50 : 1 responder cells : stimulator cells. The plates were incubated at 37° in 5% CO2 under humidified conditions for 48 hr. An indicator dye (Alamar Blue; Sigma) was added to the culture medium at 20 μl/well.18,19 Responder lymph node cells (2 × 105 cells in 200 μl of the same culture medium) without stimulator cells were cultured with the indicator dye as a control. Fluorescence was measured consecutively at various intervals over the last 72 hr of incubation (Synergy HT plate reader; Bio-TEK Instruments, Winooski, VT). The intensity of each well was calculated and expressed as follows: intensity = (sample fluorescence unit)/(control fluorescence unit). Results are shown as means ± SD.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Mice were killed 0, 3, 6 and 9 days (n = 9 at the indicated time-points) after transplantation, and RNA was extracted from the transplanted corneas, the unoperated contralateral corneas, and the DLN using TRIzol reagent (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). The corneas (4 mm in diameter) were excised from the limbus and immediately stored at − 80°. RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a PCR cDNA synthesis kit (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA). PCR was performed using sense/antisense primers. PCR conditions were as follows: for detection of 4-1BB, 4-1BBL, interleukin-10 (IL-10), and IFN-γ; 94° for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°, 1 min at 55° and 1 min at 72°, with a final extension at 72° for 5 min. For the detection of 4-1BBL and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA, annealing was performed at 60°. PCR primer sequences were as follows: mouse 4-1BB, forward 5′-TGTGTGCAGGCTATTTCAGG-3′ and reverse 5′-GAGCTGCTCCAGTGGTCTTC-3′[expected size, 504 base pairs (bp)]; mouse 4-1BBL, forward 5′-ATTCACAAACACAGGCCACA-3′ and reverse 5′-GATAAGCCCTCAGACCCAC A-3′ (expected size, 203 bp); IL-10, forward 5′-GGACAACATACTGCTAACCGACTC-3′ and reverse 5′-AAAATCACTCTT CACCTGCTCCAC-3′ (expected size, 256 bp); mouse IFN-γ, forward 5′-TGAACGCTACACACTGCATCTTGG-3′ and reverse 5′-CGACTCCTTTTCCGCTTCCT GAG-3′ (expected size, 460 bp); and mouse GAPDH, forward 5′-TGAAGGTCGGTGTGA ACGGATTTGGC-3′ and reverse 5′-CACCACCTGGAGTACCGGATGTAC-3′ (expected size, 982 bp). PCR products were visualized with ethidium bromide after electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels.

RNase protection assay (RPA)

Mice were killed on days 0, 3, 6 and 9 after transplantation (n = 9 at the indicated time-points), and total RNA was isolated from the transplanted corneas, the unoperated contralateral corneas, and the cervical DLN using Fenozol reagent (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). The corneas (4 mm in diameter) were excised from the limbus and immediately stored at −80°. Chemokine mRNA levels were quantified by RPA according to the manufacturer's instructions (Riboquant; BD PharMingen). Five micrograms of total RNA was hybridized with [α-32P]UTP-labelled riboprobes, overnight at 56°. After hybridization, unhybridized single-strand RNA was digested by RNase treatment. Double-stranded RNA was purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The samples underwent electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide/7 m urea gel, and then the gel was dried and subjected to autoradiographic analysis.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

For histopathological analysis, eyes were embedded in optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Ted Pella, Redding, CA). Sections (7-μm thick) were cut, air-dried overnight, and stained with haematoxylin & eosin (Sigma-Aldrich). For immunohistochemistry, sections were cut, air-dried and fixed in acetone at 4° for 10 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 99% methanol containing 1·0% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min at room temperature. Sections were blocked with 5% normal rabbit serum in PBS. Antibody dilutions were made in 1% normal rabbit serum-PBS. For detection of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, anti-mouse CD4 mAb (clone GK1.5; e-Biosciences) or anti-mouse CD8α mAb (clone 53-6.7) was diluted 1/100 and incubated overnight at 4°. Sections were then treated with avidin-biotinylated enzyme complex for 30 min (Vectastain Elite PK-6100 ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), followed by 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate (SK-4100 DAB Kit, Vector Laboratories), and counterstained with haematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich). Irrelevant biotinylated rat antibodies and normal rabbit serum were used as negative controls. Positive cells were counted in × 100 fields, and the distribution of positively stained cells was investigated in high-power fields (× 400 fields). Three eyes, two sections per eye, were assayed for a total of n = 6. Results are shown as means ± SD for the six samples.

Statistical analysis

Actuarial graft survival was analysed using the Kaplan–Meier survival method.20 The Mantel–Cox log-rank test was used to examine for statistical differences between the groups. Student's t-test was used to analyse MLR, cell counts in the immunohistochemistry studies, cell count data and duration of corneal opacity before graft rejection. P < 0·05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

Corneal allograft survival

All of the syngeneic grafts in WT BALB/c recipients (n =8) and B6 recipients (n = 7) survived and remained transparent throughout the 13-week observation period (data not shown). In contrast, all of the allogeneic grafts in both types of recipients were rejected. Survival of B6 donor grafts in BALB/c recipients (n = 10) ranged from 10 to 26 days, with a median survival time (MST) of 14 days. Survival of BALB/c donor grafts in B6 recipients (n = 12) ranged from 9 to 15 days, with an MST of 12 days (Table 1).

Effect of anti-4-1BB and anti-4-1BBL mAb on corneal allograft survival

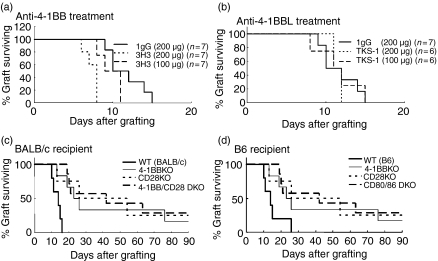

To investigate the role of the 4-1BB costimulatory pathway in the corneal allograft, we compared the BALB/c grafts transplanted into WT B6 mice treated with agonistic anti-4-1BB or blocking anti-4-1BBL (TKS-1) (Table 1). Treatment with 200 μg anti-4-1BB resulted in significantly accelerated rejection of the corneal allograft, compared with control rat IgG treatment. Treatment with a lower dose of anti-4-1BB (100 μg) resulted in some enhancement of rejection, but the effect was not significant compared with the control (Table 1, Fig. 1a). Treatment with anti-4-1BBL did not significantly affect allogeneic graft survival, compared with control rat IgG treatment (Table 1,Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Role of 4-1BB, CD28 and/or CD80/86 in the survival of corneal allografts. (a) Corneal allografts in B6 WT recipients untreated or treated with anti-4-1BB mAb. Recipients treated with anti-4-1BB showed accelerated rejection in a dose-dependent manner. The decreased survival with the larger dose was significantly different from the survival of the IgG-treated control (P < 0·0007). Graft survival data are presented as Kaplan–Meier survival curves. (b) Corneal allografts in B6 WT untreated recipients or in recipients treated with anti-4-1BBL mAbs. Treatment with anti-4-1BBL did not significantly affect allogeneic graft survival, compared with control rat IgG treatment. (c) Corneal allograft in BALB/c mice deficient in 4-1BB and/or CD28. Survival in KO recipients was significantly longer than the survival of the control WT BALB/c recipients (P < 0·0085, 0·047, and 0·0001, respectively). The 4-1BB KO, CD28KO and 4-1BB/CD28 DKO recipients had no significant difference among them. (d) Corneal allograft in B6 mice deficient for 4-1BB, CD28 or CD80/86. All of the survival in KO recipients was significantly longer than the survival of the control WT B6 recipients (P < 0·001 for 4-1BB KO, CD28 KO and P < 0·0001 for CD80/86 KO).

Survival of B6 corneal allografts in 4-1BB KO, CD28 KO, and 4-1BB/CD28 DKO BALB/c mice

To investigate the role of the 4-1BB and CD28 costimulatory pathways, we compared the B6 allograft survival in BALB/c 4-1BB KO, CD28 KO, or 4-1BB/CD28 DKO mice. Corneal allografts from WT B6 mice showed significantly enhanced graft survival in 4-1BB KO, CD28 KO, or 4-1BB/CD28 DKO BALB/c recipient mice, compared with control WT B6 grafts in WT BALB/c recipient mice. However, contrary to our expectation, there was no additive effect in 4-1BB/CD28 DKO mice (Table 1, Fig. 1c). The absence of both 4-1BB and CD28 molecules in the corneal allograft resulted in some promotion of survival, but the overlapped effect was not significant compared with the single deficiency of 4-1BB or CD28 costimulatory pathway.

Survival of BALB/c corneal allografts in 4-1BB KO, CD28 KO and CD80/86 DKO C57BL/6 mice

To investigate the role of 4-1BB and CD28/CD80/CD86 costimulatory pathways, we compared the BALB/c allograft survival in B6 4-1BB KO, CD28 KO and CD80/CD86 DKO mice. The survival of BALB/c grafts in B6 4-1BB KO, CD28 KO and CD80/CD86 DKO mice was significantly enhanced, compared with the survival of control BALB/c grafts in WT B6 mice. Among the KO mice, CD80/CD86 DKO recipients showed significantly longer survival of corneal allografts (P < 0·01) than the 4-1BB KO mice. The longest survival of the corneal grafts was seen in the CD80/CD86 DKO recipients (Table 1, Fig. 1d).

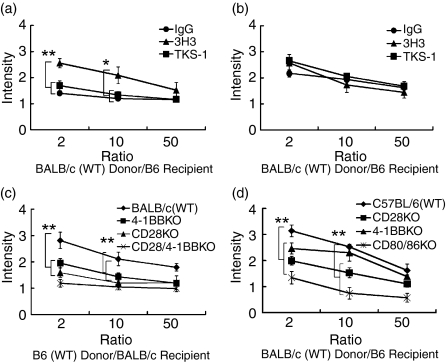

Effect of anti-4-1BB and anti-4-1BBL mAb treatment on MLR

We utilized in vitro MLR evaluation to measure on-going cellular responses that were reflective of allograft rejection. B6 recipients with BALB/c grafts were killed on days 7 and 14 after transplantation, and DLN were collected for MLR assay (n = 3 in each treatment group). Cellular proliferation was greater in the anti-4-1BB-treated group on day 7, compared with the anti-4-1BBL (TKS-1)- or IgG-treated groups (Fig. 2a). This finding was consistent with the enhanced rejection seen in the 3H3-treated recipient mice in the graft survival studies. However, no significant differences in the DLN were seen on day 14 (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Roles of 4-1BB, CD28 and/or CD80/86 in MLR. Effect of anti-4-1BB and anti-4-1BBL on MLR between WT BALB/c donor and WT B6 recipients on day 7 (a) and day 14 (b). C57BL/6 recipients were treated with either control IgG, anti-4-1BB, or anti-4-1BBL (200 μg/mouse, i.p.) on days 0, 2, 4 and 6 after transplantation. On days 7 and 14, mice were killed and DLN (cervical) cells were collected (n = 3 in each group). Enumeration of antigen-specific recall responses by in vitro MLR revealed greater proliferation in the DLN of anti-4-1BB-treated recipients on day 7, compared with anti-4-1BBL-treated or IgG-treated recipients, but no significant differences on day 14 in DLN. *P < 0·01, **P < 0·001, compared with IgG-treated WT controls. Results are shown as mean ± SD. Effect of costimulatory receptor gene deletion on MLR between WT B6 donor and BALB/c KO recipients (c), or MLR between WT BALB/c donor and B6 KO recipients (d). Both KO recipients showed reduced MLR responses on day 14 (**P < 0·001). Results are shown as means ± SD.

Effect of costimulatory receptor gene deletion on MLR

In parallel experiments, the effect of a gene deletion in the costimulatory pathways was evaluated. BALB/c (Fig. 2c) or B6 (Fig. 2d) KO recipients of allogeneic WT grafts (n = 3 in each group) were killed on day 14 after corneal transplantation, and DLN (cervical) cells were collected for MLR assay. The results demonstrated reduced proliferation in the mice with longer graft survival time.

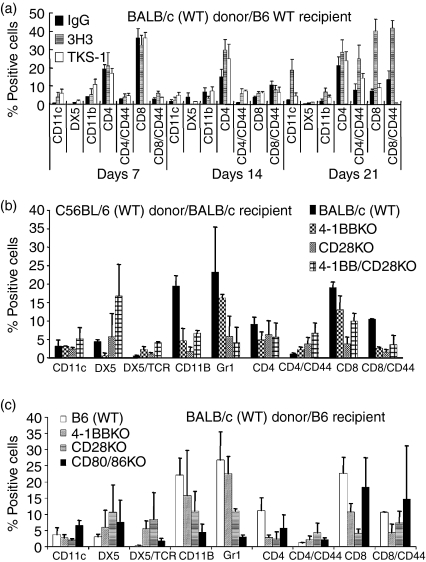

Flow cytometric analysis of infiltrating leucocytes in corneal allografts

B6 recipients with WT BALB/c grafts were treated with control IgG, anti-4-1BB, or anti-4-1BBL (200 μg) on days 0, 2, 4 and 6 after transplantation. Mice in which the grafts had opacity scores of 2–3 were killed on days 7, 14 and 21 after transplantation (n = 3 for each treatment and time period), and infiltrating leucocytes were analysed by flow cytometry. No significant differences in the infiltrating cell populations were found in the corneal allografts from anti-4-1BB- or anti-4-1BBL-treated mice on day 7, compared with IgG-treated controls. By day 14, however, the CD4+ T-cell population had increased in grafts from the anti-4-1BB-treated mice, and by day 21, increased populations of CD11c+, CD4+ and CD8+ cells were seen in the grafts from the anti-4-1BB-treated mice (Fig. 3a). CD11c+ cell infiltration in anti-4-1BBL-treated mice was significantly less than that seen in anti-4-1BB-treated mice (P = 0·018).

Figure 3.

Profiles of infiltrating leucocytes in corneal allografts by flow cytometry. (a) Mice were killed on days 7, 14 and 21 after transplantation and the population of infiltrating leucocytes in the corneal allografts was measured by flow cytometry. By day 21, CD11c+ cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells were increased in the anti-4-1BB (3H3)-treated recipients. (n = 3 in each group). (b) BALB/c recipient mice were killed on day 14 after transplantation (n = 3 in each group). 4-1BB/CD28 KO recipients showed increased numbers of DX5+ cells. All of the KO recipients showed reduced numbers of CD11b+ and CD8+ cells, and tended to have a reduced population of Gr-1+ cells, which matched the observed longer graft survival times. (c) C57BL/6 KO recipients were killed on day 14 after transplantation (n = 3 in each group). Similarly to the BALB/c recipients in (b), increased numbers of DX5+ cells, as well as reduced populations of CD11c+, Gr-1+, CD4+ and CD8+ cells, were seen in the grafts with longer survival times. The CD80/86 KO mice showed an increased CD8+ T-cell population, similar to that seen in the WT control. Results shown in (b) and (c) are representative of triplicate experiments with similar results. Data are expressed as means ± SD.

WT B6 grafts with opacity scores of 2–3 in BALB/c KO recipients were excised on day 14 and the infiltrating leucocytes were analysed. The 4-1BB/CD28 DKO recipient mice showed larger number of DX5+ cells, compared with WT BALB/c recipient controls (Fig. 3b). However, the 4-1BB KO, CD28 KO and 4-1BB/CD28 DKO mice showed smaller numbers of CD11b+ cells. Smaller numbers of Gr-1+ cells were seen in the KO recipients, which correlated with longer graft survival times in these mice.

Parallel studies in B6 KO recipients showed larger numbers of DX5+ cells in B6 CD28 KO and CD80/CD86 DKO recipients, compared with WT B6 recipients. CD80/CD86 DKO mice showed no significant difference in numbers of infiltrating CD8+ T cells, compared with WT recipients, despite the fact that this strain had the longest graft survival time among the B6 recipients. All of the B6 KO mice showed smaller numbers of CD11b+ and Gr-1+ cells, which correlates with the longer graft survival times in these groups.

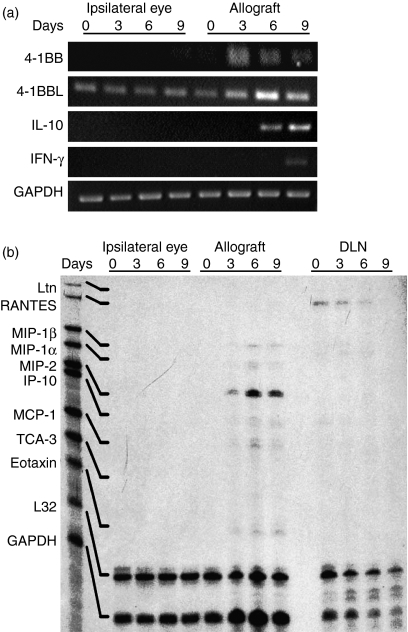

4-1BB, 4-1BBL, cytokine and chemokine gene expression during corneal allograft rejection

Expression of 4-1BB mRNA was seen in the allografted corneas but not in the normal contralateral corneas. 4-1BBL mRNA was significantly elevated in the allografted corneas compared with the normal contralateral corneas, and reached a peak on day 6 after transplantation. In the allografted corneas, IL-10 was expressed on days 6 and 9, and IFN-γ mRNA was expressed on day 9 (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

4-1BB, 4-1BBL, cytokine and chemokine gene expression during orthotopic corneal allograft rejection in B6 recipients. (a) RT-PCR was performed on total RNA isolated from corneal allografts and contralateral normal corneas (negative controls) from B6 WT recipients on days 0, 3, 6 and 9 after transplantation. 4-1BB and 4-1BBL mRNA was expressed in allografted corneas on days 3, 6 and 9. The 4-1BBL was significantly elevated on day 6 after transplantation. IL-10 mRNA was expressed on days 6 and 9, and IFN-γ mRNA on day 9 (n = 9 in each group). (b) Chemokine mRNA levels were quantified by RPA analysis. Samples from corneal allografts, contralateral normal corneas (negative control), and DLN were evaluated on days 0, 3, 6 and 9 after transplantation. On the basis of the migration patterns of undigested probes, specific bands were identified for each chemokine. In comparison with the chemokine mRNA levels in the contralateral normal corneas, the allografts showed significant expression of MIP-2 mRNA that peaked on day 6 and weak expression of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, IP-10, MCP-1 and eotaxin mRNA from days 3 to 9. Expression of Ltn, RANTES and TCA-3 was undetectable in all the eyes studied. Declining expression of RANTES was detectable in DLN from day 0 through day 6 (n = 9 in each group).

RPA (Fig. 4b) showed that the chemokine mRNAs were not expressed constitutively in the contralateral normal corneas on any of the days tested or in the allografted corneas on day 0. Thereafter, however, the allografted corneas showed weak expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β, IFN-γ-inducible protein-10 (IP-10), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and eotaxin mRNA on days 3, 6 and 9, as well as significant expression of MIP-2 mRNA that peaked on day 6. Expression of Ltn, RANTES and TCA-3 mRNA was not detected in any of the corneas. RANTES expression was detected in DLN on days 0, 3 and 6.

Histology and immunohistochemical staining of grafts

Immunohistochemical staining of rejected allografts obtained from anti-4-1BB-treated B6 or BALB/c WT or KO recipient mice on day 14 after transplantation showed heavy infiltration of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and other inflammatory cells, especially at the host–graft interface. The numbers of CD4+ T cells in the anti-4-1BB-treated group were significantly higher on days 7 and 14, compared with IgG-treated controls (P < 0·05) (Fig. 5a). Similarly, CD8+ T-cell numbers were significantly higher on day 21 (P < 0·01), compared with IgG-treated controls. Allografts from anti-4-1BBL-treated mice showed no significant differences, compared with IgG-treated controls.

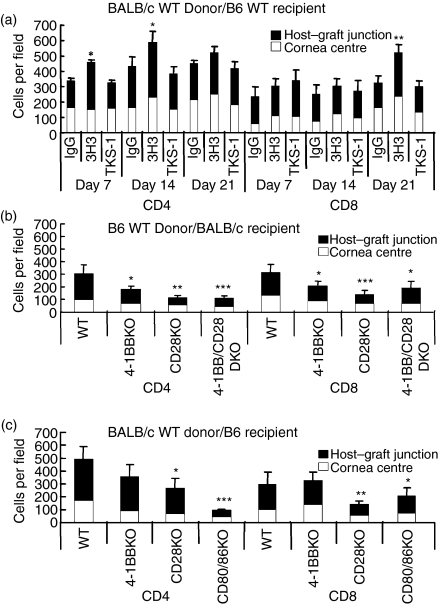

Figure 5.

Comparison of the number of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells infiltrating into corneal grafts. (a) C57BL/6 mice treated i.p. with anti-4-1BB, anti-4-1BBL, or control rat IgG (200 μg) on days 0, 2, 4 and 6 after transplantation, were killed on days 7, 14 and 21. Corneal sections were stained immunohistochemically, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were counted under × 100 magnification (two sections/eye and three eyes/time-point). Agonistic anti-4-1BB treatment significantly increased both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration into the corneal grafts. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, compared with IgG-treated WT control. Data are expressed as means ± SD. (b) BALB/c and (c) B6 WT and KO recipient mice were killed 14 days after transplantation. Corneal sections were stained immunohistochemically and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were counted under × 100 magnification (two sections/eye and three eyes/time-point). Cells were counted separately at the host–graft junction and in the central cornea. Results are shown as means ± SD. The absence of costimulatory ligands or receptors significantly decreased leucocyte infiltration into the corneal grafts. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001, compared with WT control.

Allografts from BALB/c 4-1BB KO, CD28 KO, and 4-1BB/CD28 DKO recipient mice showed reduced CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell infiltration in both host–graft junction and central cornea, in comparison with grafts from control BALB/c WT recipients. Actual CD4+ T-cell and CD8+ T-cell numbers were significantly reduced in these grafts (Fig. 5b).

Allografts from B6 CD28 KO and CD80/CD86 DKO recipient mice also showed reduced cellular infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at both the host–graft junction and in the central cornea, and were nearly free of inflammatory cells, in comparison with the B6 WT or B6 4-1BB KO allografts. Actual CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell numbers were significantly reduced in the allografts from the B6 CD28 KO and CD80/CD86 DKO recipient mice, compared with the B6 WT recipients (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

We have studied the role and functional importance of 4-1BB/4-1BBL and/or CD28/CD80/CD86 costimulatory pathways in the rejection of an allogeneic corneal graft. The results provide three new and significant insights: (1) agonistic anti-4-1BB accelerated corneal allograft rejection, whereas 4-1BB-deficient mice showed prolonged allograft survival; (2) recipient mice deficient of CD28 or 4-1BB gene showed somewhat prolonged allograft survival, but did not display the additive effect of the combined deficiency of 4-1BB and CD28; and (3) B6 mice deficient for the CD80 and CD86 genes demonstrate much longer allograft survival than B6 4-1BB KO recipients.

Treatment of WT recipients with anti-4-1BB accelerated graft rejection and anti-4-1BBL showed no effect on corneal allograft survival, whereas the 4-1BB KO recipients showed prolonged corneal allograft survival. Blockade of 4-1BB/4-1BBL interactions has been previously reported to increase cardiac allograft survival in 4-1BB KO mice.11 Cho et al. also reported that anti-4-1BBL had a much greater suppressive effect on cardiac allograft rejection compared with 4-1BB-deficient recipients.11 DeBenedette et al.21 reported that 4-1BBL-deficient mice showed a delay in skin allograft rejection only on a CD28-deficient background. Several possibilities may account for this discrepancy. One is that 4-1BB-deficient recipients can completely block the interaction between 4 and 1BB and 4-1BBL, in comparison with anti-4-1BBL treatment which may provide only partial blockade. Another possibility may be that the cornea is an avascular tissue, and that the antigen-presenting mechanism after corneal transplantation may be different from that in vascularized tissue such as is found in a cardiac graft. In other words, anti-4-1BBL may not completely block an interaction between 4 and 1BB and 4-1BBL.

A striking finding was the absence of an additive effect of deficiency in both 4-1BB and CD28. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a corneal allo-transplantation using 4-1BB KO and 4-1BB/CD28 DKO recipient mice. Our data suggest that the combined blockade of both the 4-1BB and CD28 costimulatory pathways somewhat enhances corneal allograft survival, compared with the blockade of each pathway alone, but the differences in lengths of survival were not statistically significant. We have earlier reported that 4-1BB co-operates with CD28, in the context of T-cell receptor/CD3 ligation, to amplify the T-cell immune response.22 Our previous studies and the studies of others have indicated that anti-4-1BB costimulation had a profound effect upon the up-regulation of IFN-γ production by CD8+ cells, but had no effect on IL-4 and IL-10 production and in contrast, anti-CD28 costimulation had only a slight effect on IFN-γ production in either subset. In contrast, anti-CD28 costimulation markedly enhanced IL-2, IL-4 and IL-10 production in CD4+ T cells.8,25 The deficiency of 4-1BB on CD28 KO background (4-1BB/CD28 DKO) does not display any of the aspects associated with 4-1BB KO mice, but continues to exhibit the characteristics of CD28-deficient mice.15 This is one of the potential explanations; the role of 4-1BB may be negligible without CD28 in allograft responses. In fact, 4-1BB and 4-1BBL are an inducible costimulatory receptor/ligand and their expressions require antigen stimulation and constitutive costimulatory signals such as CD28.12

Another finding was that B6 mice deficient for CD80 and CD86 genes demonstrated much longer allograft survival than B6 4-1BB KO recipients, while corneal allograft survival between 4 and 1BB KO and CD28 KO recipients showed few significant differences. It has been reported that the combined use of anti-CD80 and anti-CD86 mAbs is effective in prolonging corneal allograft survival, demonstrating a significant role for the CD28/CD80/CD86 costimulatory pathway in the induction of allogeneic responses after corneal transplantation.7 It has also been reported that corneal allograft rejection in CD28 KO mice treated with CTLA-4–immunoglobulin was accelerated, compared with that in untreated CD28 KO.6 This is in agreement with the results of cardiac transplantation23 and is probably the result of blocking negative signalling interactions between CD80/CD86 and CTLA-4 (CD152) on activated T cells. Taken together, CD80/CD86 expression in the recipient APCs probably plays a much more significant role than expression in the donor graft, and the lack of both CD80 and CD86 molecules on recipient APCs might be more effective for allograft survival than simply the deficiency of 4-1BB or CD28 on T cells.

Although we have not examined the roles of regulatory T cells in the present studies, it is important to address their roles in different combinations of corneal allografts in future investigations.

In conclusion, we have shown that, although blockade of these different costimulatory pathways at the time of transplantation is effective in extending graft survival, it does not abolish allograft rejection. Our data provide direct evidence that the 4-1BB/4-1BBL pathway also plays an important role in corneal allograft rejection, similar to the CD28/CD80/CD86 costimulatory pathways. Taken together, these data suggest that blockade of the 4-1BB/4-1BBL and/or CD28/CD80/CD86 costimulatory pathways promotes corneal allograft survival.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Josie Everly and Edwin Kwon for their editorial assistance. These studies were supported in part by USPHS grants R01EY013325 (BSK) and P30EY002377 (LSU Eye Center core grant) from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; grants KRF-2005-201-E00008 and KRF-2005-084-E00001 from the Korean Research Foundation; and the SRC Fund to the IRC at the University of Ulsan from KOSEF and the Korean Ministry of Science and Technology.

Abbreviations

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- bp

base pairs

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4

- DAB

3,3-diaminobenzidine

- DKO

double knockout

- DLN

draining lymph nodes

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IL-10

interleukin-10

- i.p.

intraperitoneally

- IP

inducible protein

- KO

knockout

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MCP

monocyte chemoattractant

- MIP

macrophage inflammatory protein

- MLR

mixed lymphocyte reaction

- MST

median survival time

- NK

natural killer cells

- OCT

optimal cutting temperature

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PE

phycoerythrin

- RPA

RNase protection assay

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

- WT

wild-type

References

- 1.Lindstrom RL. Advances in corneal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:57–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607033150110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price FW, Jr, Whitson WE, Collins KS, Marks RG. Five-year corneal graft survival. A large, single-center patient cohort. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:799–805. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090060087029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrack P, Kappler J. The T cell receptor. Science. 1987;38:1073–9. doi: 10.1126/science.3317824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comer RM, King WJ, Ardjomand N, Theoharis S, George AJ, Larkin DF. Effect of administration of CTLA4-Ig as protein or cDNA on corneal allograft survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1095–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffmann F, Zhang EP, Pohl T, Kunzendorf U, Wachtlin J, Bulfone-Paus S. Inhibition of corneal allograft reaction by CTLA4-Ig. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1997;235:535–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00947013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ardjomand N, McAlister JC, Rogers NJ, Tan PH, George AJ, Larkin DF. Modulation of costimulation by CD28 and CD154 alters the kinetics and cellular characteristics of corneal allograft rejection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3899–905. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kagaya F, Hori J, Kamiya K, et al. Inhibition of murine corneal allograft rejection by treatment with antibodies to CD80 and CD86. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74:131–9. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinay DS, Kwon BS. Role of 4-1BB in immune responses. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:481–9. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melero I, Johnston JV, Shuford WW, Mittler RS, Chen LNK. 1.1 cells express 4-1BB (CDw137) costimulatory molecules and are required for tumor immunity elicited by anti-4-1BB monoclonal antibodies. Cell Immunol. 1998;190:167–72. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon B, Moon CH, Kang S, Seo SK, Kwon BS. 4-1BB. still in the midst of darkness. Mol Cells. 2000;30:119–26. doi: 10.1007/s10059-000-0119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho HR, Kwon B, Yagita H, et al. Blockade of 4-1BB (CD137)/4-1BB ligand interactions increases allograft survival. Transpl Int. 2004;17:351–61. doi: 10.1007/s00147-004-0726-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon BS, Hurtado JC, Lee ZH, et al. Immune responses in 4-1BB (CD137)-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:5483–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinay DS, Wolisi GO, Yu KY, Choi BK, Kwon BS. Immunity in the absence of CD28 and CD137 (4-1BB) molecules. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;81:176–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2003.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.She SC, Steahly LP, Moticka EJ. A method for performing full-thickness, orthotopic, penetrating keratoplasty in the mouse. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990;21:781–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonoda Y, Streilein JW. Orthotopic corneal transplantation in mice – evidence that the immunogenetic rules of rejection do not apply. Transplantation. 1992;54:694–704. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199210000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sano Y, Ksander BR, Streilein JW. Minor H, rather than MHC, alloantigens offer the greater barrier to successful orthotopic corneal transplantation in mice. Transpl Immunol. 1996;4:53–6. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(96)80035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers NJ, Mirenda V, Jackson I, Dorling A, Lechler RI. Costimulatory blockade by the induction of an endogenous xenospecific antibody response. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:163–8. doi: 10.1038/77853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhi-Jun Y, Sriranganathan N, Vaught T, Arastu SK, Ahmed SA. A dye-based lymphocyte proliferation assay that permits multiple immunological analyses: mRNA, cytogenetic, apoptosis, and immunophenotyping studies. J Immunol Meth. 1997;210:25–39. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwack K, Lynch RG. A new non-radioactive method for IL-2 bioassay. Mol Cells. 2000;10:575–8. doi: 10.1007/s10059-000-0575-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeBenedette MA, Wen T, Bachmann MF, Ohashi PS, Barber BH, Stocking KL, Peschon JJ, Watts TH. Analysis of 4-1BB ligand (4-1BBL)-deficient mice and of mice lacking both 4-1BBL and CD28 reveals a role for 4-1BBL in skin allograft rejection and in the cytotoxic T cell response to influenza virus. J Immunol. 1999;163:4833–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurtado JC, Kim SH, Pollok KE, Lee ZH, Kwon BS. Potential role of 4-1BB in T cell activation: comparison with the costimulatory molecule CD28. J Immunol. 1995;155:3360–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin H, Rathmell JC, Gray GS, Thompson CB, Leiden JM, Alegre ML. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) blockade accelerates the acute rejection of cardiac allografts in CD28-deficient mice. CTLA4 can function independently of CD28. J Exp Med. 1998;188:199–204. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]