Abstract

The outcome of an encounter between a cytotoxic cell and a potential target cell depends on the balance of signals from inhibitory and activating receptors. Natural Killer group 2D (NKG2D) has recently emerged as a major activating receptor on T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. In both humans and mice, multiple different genes encode ligands for NKG2D, and these ligands are non-classical major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. The NKG2D–ligand interaction triggers an activating signal in the cell expressing NKG2D and this promotes cytotoxic lysis of the cell expressing the ligand. Most normal tissues do not express ligands for NKG2D, but ligand expression has been documented in tumour and virus-infected cells, leading to lysis of these cells. Tight regulation of ligand expression is important. If there is inappropriate expression in normal tissues, this will favour autoimmune processes, whilst failure to up-regulate the ligands in pathological conditions would favour cancer development or dissemination of intracellular infection.

Keywords: NKG2D, activating receptor, MICA, RAET1, UL16

Introduction

Cytotoxic cells express a range of activating receptors including Natural Killer group 2D (NKG2D), 2B4, NKp80 and the natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs) NKp30, NKp44 and NKp46.1 The NKG2D receptor is a key activating receptor on natural killer (NK) and T cells. NK cell stimulation through activating receptors is opposed by signalling through inhibitory receptors such as the killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) molecules, NKR-P1 and CD94/NKG2(A/B), which are also expressed on cytotoxic NK cells and recognize ‘self’ major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules expressed on healthy cells. The inhibitory CD94/NKG2A and CD94/NKG2B receptors recognize the non-classical MHC class I molecule human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-E, which can be thought of as a ‘marker’ for intracellular health.2–4 This interaction prevents the activation of the effector cell and the subsequent lysis of the cell expressing HLA-E. Loss of expression of MHC class I molecules in pathological conditions abolishes the inhibitory signal to cytotoxic effector cells. According to the ‘missing self’ hypothesis, failure to express these indicators of health allows the inhibitory signals to cytotoxic cells to be overridden by triggering of activating receptors, which leads to target cell lysis by effector cells.5,6 However, tumour and virus-infected cells not only down-regulate or lose the expression of MHC class I molecules, but can also induce the expression of other ‘self’ molecules that are markers of cellular stress. A set of these molecules is recognized by the NKG2D activating receptor, which has been considered a dominant activating receptor, such that triggering of NKG2D can induce cytotoxic lysis of the stressed target cells expressing ligands for NKG2D, despite the expression of normal levels of MHC class I molecules.7,8 The current consensus is that NK cell activation and cytotoxicity result from the integration of signals produced by ‘missing self’ and ‘induced self’ interactions and a shifting of the balance in the signalling strength between the inhibitory and activating receptors (reviewed by Malarkannan9).

NKG2D is a C-type lectin-like molecule. The archetypal C-type lectins bind carbohydrates in a Ca2+-dependent manner through a common structural motif, but NKG2D has no features to suggest that it binds carbohydrates. It is a homodimeric type II transmembrane glycoprotein encoded on human chromosome 12, within the NK gene complex, and in a syntenic position on mouse chromosome 6.10 Human NKG2D is expressed on NK cells, CD8+ T-cell receptor (TCR)-αβ T cells and TCR-γδ T cells. Murine NKG2D is also expressed on NK cells, but is only present on activated and memory CD8+ TCR-αβ T cells and only 25% of splenic TCR-γδ T cells. Neither mouse nor human NKG2D is normally expressed on CD4+ TCR-αβ T cells. Murine NKG2D has also been detected on NKT cells, some interferon-producing killer dendritic cells, and at the mRNA level in macrophages (reviewed by Coudert and Held10).

Signalling through NKG2D

Certain activating NK cell receptors, such as the NCR, associate with a transmembrane signalling adaptor molecule, which possesses an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM). These adaptors include CD3ζ, FcεRIγ and DAP12.1 There are two isoforms of NKG2D in the mouse, which differ in the length of their intracellular cytoplasmic tail. The shorter form is known to associate with ITAM-bearing DAP12, which transduces the NKG2D activating signal via recruitment of the ZAP-70 and Syk tyrosine kinases. However, the cytoplasmic tail of the longer form appears to prevent interaction with this adaptor.10,11 Both forms of murine NKG2D can also associate with another adaptor molecule, DAP10, which lacks an ITAM but instead bears a YxxM motif for Src homology 2 (SH2) domain binding.12 NKG2D engagement results in the phosphorylation of DAP10 by Src family kinases and recruitment of the p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Grb2, and ultimately leads to calcium flux and cytotoxicity.11 The short form of murine NKG2D is only expressed in activated NK cells, whilst the long form is constitutively expressed. Human NKG2D has no short form and only associates with DAP10. In both humans and mice, NKG2D signalling through DAP10 is sufficient for cell-mediated cytotoxicity (reviewed by Upshaw and Leibson11).

Role of NKG2D in primary activation and costimulation

On activated NK cells, NKG2D serves as a primary activation receptor, such that NKG2D engagement alone is sufficient to trigger NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. In contrast, NKG2D appears to act as a costimulatory receptor in CD8+ T cells, requiring TCR-mediated signalling for full activation of these effector cells (reviewed10). There is controversy over whether NKG2D is capable of mediating activation in the absence of other stimuli in T cells13–16. The actual function of NKG2D may be determined by additional factors, such as the activation status of the effector cell or the cellular environment e.g. effector cell priming by exposure to cytokines (reviewed by Coudert and Held10).

Overview of NKG2D ligands

A distinctive feature of the NKG2D system is that there are multiple ligands for this receptor, all of which are distantly related homologues of MHC class I proteins. The first ligands identified were the MHC class I chain-related proteins (MIC) A and MICB, which are encoded within the human MHC (6p21.3).17 Their sequence homology to MHC class I proteins is only approximately 25%, and although they have α1, α2 and α3 domains, they do not associate with β2-microglobulin or peptide.17,18 There are no known orthologues of the MIC molecules in the mouse MHC. However, MIC molecules are conserved in non-human primates, cattle and pigs.17,19,20 A second family of NKG2D ligands, the UL16 binding protein (ULBP) family, is encoded outside the MHC (6q24.2–25·3).21 The ULBPs are also known as the retinoic acid early transcript 1 (RAET1) family, as they show sequence homology to the mouse retinoic acid early 1 (Rae1) proteins (Rae1α-ε). In total there are 10 members of the human RAET1 gene family, of which only five are expressed and encode functional proteins, which are able to bind NKG2D.21,22 The ULBPs were named for their ability to bind the human cytomegalovirus UL16 protein23 although it is now known that only ULBP1, ULBP2 and RAET1G bind UL16.22,24–26 MICB has also been shown to associate with UL16.27 Like the MIC proteins, RAET1E and RAET1G are type I transmembrane proteins,22 whilst ULBP1–3 are glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked proteins.21 The ULBP/RAET1 family lack an α3 domain and contain only α1 and α2 domains. Mapping close to the murine Raet1 genes on chromosome 10 are H60 and murine ULBP-like transcript 1 (MULT1), ligands for murine NKG2D for which there are no human equivalents.20 The various human and mouse ligands are presented in Fig. 1, and the evolutionary relationships between the ligands are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 1.

Multiple ligands for the human and mouse NKG2D receptor. Like major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules, MHC class I chain related proteins (MIC) A and MICB have α1, α2 and α3 extracellular domains and transmembrane domains. The remaining human and mouse ligands lack the α3 extracellular domain. Within the UL16 binding protein (ULBP) family, retinoic acid early transcript 1E (RAET1E) and RAET1G also have transmembrane domains, whilst ULBP1–3 are glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked proteins. Murine retinoic acid early 1 (Rae1) proteins are also GPI-linked to the membrane, whilst H60 and murine ULBP-like transcript 1 (MULT1) harbour transmembrane domains. The equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) for the NKG2D–ligand interactions, as determined by surface plasmon resonance studies, are also presented (ND, not determined).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree illustrating the evolutionary relationships between the different human (dark grey) and mouse (light grey) NKG2D ligands, generated using Clustalw (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/). Accession numbers: MHC class I chain related proteins (MIC) A, NP_000238; MICB, NP_005922; UL16 binding protein 1 (ULBP1), NP_079494; ULBP2, NP_079493; ULBP3, NP_078794; retinoic acid early transcript 1E (RAET1E), NP_631904; RAET1G, NP_001001788; retinoic acid early 1α (Rae1α), NP_033042; Rae1β, NP_033043; Rae1γ, NP_033044; Rae1δ, NP_064414; Rae1ε, NP_937836; H60, NP_034530; murine ULBP-like transcript 1 (MULT1), NP_084251.

Structural and binding studies of NKG2D interactions

A key question is whether the different ligands are equivalent in their capacities to trigger NKG2D signalling. Structural and binding studies have been carried out for some of the ligand interactions.28–32 The different ligands bind to relatively equal surface areas on the same region of NKG2D, but significant differences in affinities exist and may have functional implications.30 The affinities of binding range from around 6 nm to 1 µm for the interactions that have been investigated to date (Fig. 1), and structural and binding studies suggest that the ligands can compete with each other for receptor binding.30

Polymorphism of MIC genes

The MIC molecules are encoded by the most highly polymorphic human genes after the standard HLA molecules. At least 60 and 25 alleles have been identified for MICA and MICB, respectively,20,33 and the various alleles have different affinities for NKG2D as measured by the interaction of soluble recombinant NKG2D with the surface of cells transfected with different MICA alleles.34 Unlike the classical MHC class I molecules in which polymorphisms cluster in the exons encoding the peptide-binding α1 and α2 domains, polymorphisms in MICA and MICB are evenly distributed throughout the entire genes.20 The functional significance of MIC polymorphisms is not yet well understood, although there is some evidence for selective pressure generating this diversity (reviewed by Stephens17). There are documented disease associations with certain alleles of MICA, including genetic linkage to Crohn's disease, type I diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis and Behçet's disease (reviewed by Bahram et al.20), although some of these associations could arise from linkage disequilibrium with the HLA genes or with other neighbouring genes.

Role of NKG2D in the pathogenesis of tumours and other diseases

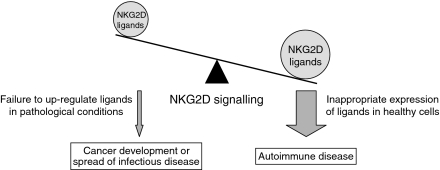

NKG2D signalling is of particular importance as deregulation of this system could have detrimental consequences. Failure to stimulate effector cytotoxic cells through this receptor in pathological conditions could lead to tumorigenesis or dissemination of intracellular infection. Conversely, inappropriate signalling through NKG2D in healthy cells could result in autoimmune disease (Fig. 3). Most of the data regarding association of the NKG2D system with autoimmune disease relate to the MIC molecules.35 Aberrant expression of NKG2D ligands, which inappropriately activate NKG2D, has been linked to rheumatoid arthritis, coeliac disease and type I diabetes mellitus.35

Figure 3.

Stringent regulation of NKG2D ligands is important. Failure to up-regulate the ligands in pathological situations, resulting in too little NKG2D signalling (left), can lead to the development of cancer, or the spread of infection. Conversely, inappropriate expression of the ligands, and hence too much NKG2D signalling in healthy cells (right), can lead to autoimmune disease.

NKG2D plays a critical role in the elimination of tumour cells by cytotoxic effector cells.7,8,23,36–41In vitro studies have demonstrated that the expression of an NKG2D ligand is sufficient to trigger cytolysis by an effector cell expressing NKG2D.15,40,42–45 Furthermore, the formation of tumours could be prevented through NKG2D signalling.46,47 Therefore, NKG2D is important both in tumour immunosurveillance to prevent tumour initiation and also in immune-mediated rejection of tumour cells to prevent tumour progression.

The significance of NKG2D signalling in protecting against infection and tumorigenesis is highlighted by the development of mechanisms by viruses and tumour cells to evade detection by this system. NKG2D is down-regulated on effector cells following chronic exposure to its ligands on tumour cells, which results in defective NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity.46,48,49 The cell surface expression of ligands for NKG2D is also down-regulated by proteolytic shedding mediated by metalloproteinases that are secreted by tumour cells.50–53 This results in the release of soluble forms of the ectodomains of these ligands, which have been detected in the sera of patients with a number of different cancers.51,54 Not only does this mechanism down-regulate ligand expression on target tumour cells, but soluble MICA released by tumour cells also causes the internalization and lysosomal degradation of NKG2D, and hence a reduction in NKG2D levels on NK cells and CD8+ T cells.51,55 Furthermore, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β produced by tumour cells and human and mouse CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells down-regulates both NKG2D and its ligands on cytotoxic effector and tumour cells, respectively.10 Viruses have also developed mechanisms to avoid alerting the immune system through NKG2D. The human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein UL16 binds ULBP1, ULBP2 and MICB, and retains these molecules intracellularly, thereby reducing cell surface expression levels and susceptibility to NK cell cytotoxicity.24,25,27,56 Furthermore, murine cytomegalovirus proteins can also down-regulate the mouse NKG2D ligands.20

Expression of NKG2D ligands in normal healthy cells

Most normal healthy tissues do not express ligands for NKG2D,57–59 but there are exceptions to this general rule. There is developmental regulation of the ligands during embryonic development. Murine Rae1β and Rae1γ are expressed at the transcript level in the early embryo, particularly in the brain.57,59 There is also evidence for developmental regulation during normal haematopoiesis. Ligand expression (mainly ULBP1) is detected on the surfaces of B cells, platelets, monocytes and granulocytes in peripheral blood from healthy donors, but is absent on erythrocytes, monocyte-derived dendritic cells, T cells and NK cells.60 Bone marrow (BM)-derived CD34+ progenitor cells are negative for ULBP1–3 expression, but ligand expression (in particular ULBP1) is induced during normal myeloid differentiation, characterized by loss of the CD34 early haematopoietic marker and expression of the myeloid markers CD33 and CD14.60 ULBP1 expression can also be induced by in vitro culture of CD34+ cells with myeloid growth and differentiation factors.60 Furthermore, retinoic acid-induced differentiation of embryocarcinoma cells stimulated expression of Rae1,57 consistent with the idea that NKG2D ligands are developmentally regulated. High levels of MICA, ULBP1 and ULBP3, and lower levels of ULBP2, are also detected on BM stromal cells,61 and NKG2D ligands, in particular ULBP3, have been shown to be expressed on human mesenchymal stem cells.62 Furthermore, murine Rae1 and H60 are expressed on BM cells (mainly myeloid progenitors) from BALB/c mice after repopulation of an irradiated host.63 Interestingly, expression of these ligands appears to be strain-dependent, as C57BL/6 BM cells express little NKG2D ligand. Indeed, both single positive and double positive thymocytes from BALB/c, but not from C57BL/6, mice express ligands for NKG2D.43,64

Both MICA and MICB are expressed on normal intestinal epithelial cells.58 This is believed to result from stimulation by bacterial flora in the gut. At the mRNA level, there is also some evidence that the ULBPs are expressed in other healthy tissues.23,65 Similarly, MULT1 mRNA is detected in a number of normal tissues.29,66 However, cell surface expression levels of the ligands were not investigated in these studies, and there have been some reports that the expression of ULBP mRNA does not always correlate with cell surface expression levels in peripheral blood60 and in tumour cell lines,23 which suggests regulation of ULBP expression at a level other than transcription.

Up-regulation of NKG2D ligands in activated immune cells

NKG2D ligand expression can also be induced when immune cells are activated, such as when B cells are treated with concanavalin A (ConA) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS)43 and when T cells are stimulated with a variety of stimuli such as phytohemagglutinin (PHA), ConA, or anti-CD3 or anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody plus phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate.43,67–70 MICA and MICB are induced on dendritic cells after interferon (IFN)-α stimulation71 and ULBP1 is up-regulated on the surface of normal monocytes and leukaemic blasts in response to growth factors plus IFN-γ treatment.60 High doses of LPS induce the transcription and cell surface expression of ULBP1-3 and the cell surface expression of constitutively transcribed MICA on human macrophages, which triggers NKG2D-mediated NK cell cytotoxicity.72

Expression of NKG2D ligands on tumour cells

NKG2D ligands are constitutively expressed on a wide variety of tumour cells and tumour cells lines.36,50,51 Transformation alone is not sufficient for induction of ligand expression, as expression of a number of oncogenes (K-ras, c-myc, Akt, E6, E7, E1A or Ras V12) in murine ovarian cells did not up-regulate NKG2D ligands.73 However, when ovarian cell lines transformed with K-ras and c-myc or Akt and c-myc were implanted into the ovaries of nude mice, this resulted in the formation of tumours, and high levels of NKG2D ligand were detected in cell lines established from these tumours.73 This suggests that ligand expression is acquired during some stage of the process of tumorigenesis. However, there are some conflicting reports which demonstrate that E1A expression is sufficient to up-regulate mouse and human NKG2D ligands in primary mouse cells, and mouse and human tumour cell lines,74 and that pharmacological and siRNA-mediated silencing of BCR/ABL activity or oncogene expression could down-regulate MICA and MICB cell surface expression in the K562 chronic myelogenous leukaemia cell line.75 Loss of tumour suppressor function has also been shown to up-regulate NKG2D ligands. Rae1ε cell surface expression is enhanced on JunB-deficient cells.76 However, absence of the tumour suppressor p53 does not induce expression of any of the murine ligands.73 The constitutive expression of NKG2D ligands on some tumour cells may result from chronic activation of the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase, which plays a key role in the DNA damage response pathway.73

It is important to note that each of the NKG2D ligands has diverse expression patterns on tumour cells.23,36,77 This may reflect functional differences among the various ligands. The MIC ligands are frequently found on epithelial tumours derived from various tissues, but not commonly on haematological maligancies. In general, the ULBP family displays a converse pattern of expression; they are infrequently found on epithelial tumours, but are commonly found on T-cell leukaemia cell lines and have been detected on leukaemic cells from patients (reviewed by Coudert and Held10).

Up-regulation of NKG2D ligands on infected cells

NKG2D ligand expression is readily detected on cells infected with bacteria78,79 or viruses.24,56 MICA expression was increased in epithelial cell lines following infection by adherent Escherichia coli,79 in dendritic and epithelial cells after Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection,80 and in cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts and endothelial cells.81 Human macrophages infected with influenza virus or Sendai virus exhibited augmented levels of MICB.82

Stimuli known to up-regulate NKG2D ligand expression

Heat shock treatment up-regulates MICA on epithelial cells.58 Indeed, the MICA and MICB promoters contain heat shock transcriptional elements similar to those found in the promoters of heat shock proteins, such as heat shock protein 70 (HSP70).58 Oxidative stress has also been shown to increase MICA and MICB transcript levels in a colon carcinoma cell line.83 Recently, a wide variety of stimuli causing genotoxic stress or resulting in DNA replication arrest, including treatments with ionizing radiation, cisplatin, aphidicolin, mitomycin C or hydroxyurea, were shown to significantly up-regulate NKG2D ligands in transformed murine ovarian epithelial cells and normal adult fibroblasts, and in human secondary foreskin fibroblasts.73 The DNA damage response pathway, initiated by the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) or ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related (ATR) kinases, was implicated in the regulation of NKG2D ligands in response to these insults. Inhibition of ATM, of ATR and of a downstream mediator of these pathways, Checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1), suppressed the observed up-regulation of the ligands for NKG2D in response to the different treatments,73 demonstrating that these pathways play an important role in ligand regulation. Interestingly, p53, which is also a downstream mediator of the ATM/ATR pathways,84,85 was not necessary for the induction of ligand expression in response to the various treatments.73 Treatments that modify chromatin, resulting in a more open structure, have also been shown to up-regulate NKG2D ligand expression.73,86

Molecular mechanisms triggering NKG2D ligand expression

Relatively little is known about the molecular mechanisms that trigger NKG2D ligand gene expression.58,68,73,77,87–89 The DNA damage response pathway is frequently activated in cells infected with viruses and in tumour cells.73,90,91 Furthermore, the induction of MICA expression following T-cell activation was shown to involve the phosphorylation of ATM.70 Therefore, it is possible that this pathway could play a common essential role in NKG2D ligand induction in tumorigenesis, infection and T-cell activation, as well as in other situations of cellular stress caused by DNA damage and DNA replication inhibition. Heat shock transcriptional elements58,87,88 and nuclear factor (NF)-κB signalling68,70 have also been implicated in the regulation of MICA. Figure 4 illustrates the variety of stimuli that can induce the expression of NKG2D ligands, and some of the regulatory pathways that have been documented to date.

Figure 4.

A variety of stimuli that can regulate NKG2D ligands (NKG2DL) have been identified. However, little is known about the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of these ligands. There is evidence of transcriptional regulation, but the ligands may also be regulated at a level other than transcription. The solid arrows demonstrate the major regulatory pathways that have been identified. Indirect or less well-established pathways are shown as dotted arrows (ATM, ataxia telangiectasia mutated; ATR, ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related; Chk1, Checkpoint kinase 1; ConA, concanavalin A; IFN, interferon; IR, ionizing radiation; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NF, nuclear factor; PHA, phytohemagglutinin; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate).

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Some conventional therapies against cancer may already target NKG2D signalling through up-regulation of the ligands for this receptor, in addition to directly having cytotoxic and other effects.73 It is clear that tight regulation of NKG2D ligands is essential to ensure effective tumour immunosurveillance and rejection, and elimination of pathogen-infected cells, whilst also preventing inappropriate killing of healthy cells, which could lead to autoimmune disease. Perhaps this can explain the evolution of the multitude of NKG2D ligands, which are distinct in terms of their tissue expression patterns, levels and kinetics of expression, and affinities for their common receptor, suggesting that they are not simply redundant in function. It is entirely conceivable that the expression of the different ligands is governed by the type and degree of cellular or environmental stress, which can ultimately direct an appropriate and adequate response through NKG2D signalling. Furthermore, this diversity may be a consequence of selective pressure exerted by viruses and tumours, which have used a range of mechanisms to evade detection by NKG2D. Future investigations directed at dissecting the mechanisms controlling the regulation of NKG2D ligands should offer a better understanding of the role of the NKG2D system in immunity and how deregulation of this system results in disease, and also the potential for using NKG2D ligands as targets for therapy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Charita Christou, Aleksandra Watson, Da Lin, Gerald Moncayo and Zoe Lundy for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Moretta A, Bottino C, Vitale M, Pende D, Cantoni C, Mingari MC, Biassoni R, Moretta L. Activating receptors and coreceptors involved in human natural killer cell-mediated cytolysis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braud VM, Allan DS, O'Callaghan CA, et al. HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature. 1998;391:795–9. doi: 10.1038/35869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Callaghan CA. Molecular basis of human natural killer cell recognition of HLA-E (human leucocyte antigen-E) and its relevance to clearance of pathogen-infected and tumour cells. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;99:9–17. doi: 10.1042/cs0990009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Callaghan CA. Natural killer cell surveillance of intracellular antigen processing pathways mediated by recognition of HLA-E and Qa-1b by CD94/NKG2 receptors. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:371–80. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karre K, Ljunggren HG, Piontek G, Kiessling R. Selective rejection of H-2-deficient lymphoma variants suggests alternative immune defence strategy. Nature. 1986;319:675–8. doi: 10.1038/319675a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ljunggren HG, Karre K. In search of the ‘missing self’: MHC molecules and NK cell recognition. Immunol Today. 1990;11:237–44. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90097-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerwenka A, Baron JL, Lanier LL. Ectopic expression of retinoic acid early inducible-1 gene (RAE-1) permits natural killer cell-mediated rejection of a MHC class I-bearing tumor in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11521–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201238598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diefenbach A, Jensen ER, Jamieson AM, Raulet DH. Rae1 and H60 ligands of the NKG2D receptor stimulate tumour immunity. Nature. 2001;413:165–71. doi: 10.1038/35093109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malarkannan S. The balancing act: inhibitory Ly49 regulate NKG2D-mediated NK cell functions. Semin Immunol. 2006;18:186–92. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coudert JD, Held W. The role of the NKG2D receptor for tumor immunity. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:333–43. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Upshaw JL, Leibson PJ. NKG2D-mediated activation of cytotoxic lymphocytes: unique signaling pathways and distinct functional outcomes. Semin Immunol. 2006;18:167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J, Song Y, Bakker ABH, Bauer S, Spies T, Lanier LL, Phillips JH. An activating immunoreceptor complex formed by NKG2D and DAP10. Science. 1999;285:730–2. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meresse B, Chen Z, Ciszewski C, et al. Coordinated induction by IL15 of a TCR-independent NKG2D signaling pathway converts CTL into lymphokine-activated killer cells in celiac disease. Immunity. 2004;21:357–66. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verneris MR, Karami M, Baker J, Jayaswal A, Negrin RS. Role of NKG2D signaling in the cytotoxicity of activated and expanded CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2004;103:3065–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maccalli C, Pende D, Castelli C, Mingari MC, Robbins PF, Parmiani G. NKG2D engagement of colorectal cancer-specific T cells strengthens TCR-mediated antigen stimulation and elicits TCR independent anti-tumor activity. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2033–43. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nitahara A, Shimura H, Ito A, Tomiyama K, Ito M, Kawai K. NKG2D ligation without T cell receptor engagement triggers both cytotoxicity and cytokine production in dendritic epidermal T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1052–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens HA. MICA and MICB genes: can the enigma of their polymorphism be resolved? Trends Immunol. 2001;22:378–85. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01960-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bahram S, Bresnahan M, Geraghty DE, Spies T. A second lineage of mammalian major histocompatibility complex class I genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;96:6879–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seo JW, Walter L, Gunther E. Genomic analysis of MIC genes in rhesus macaques. Tissue Antigens. 2001;58:159–65. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.580303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bahram S, Inoko H, Shiina T, Radosavljevic M. MIC and other NKG2D ligands: from none to too many. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:505–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radosavljevic M, Cuillerier B, Wilson MJ, et al. A cluster of ten novel MHC class I related genes on human chromosome 6q24.2-q25.3. Genomics. 2002;79:114–23. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bacon L, Eagle RA, Meyer M, Easom N, Young NT, Trowsdale J. Two human ULBP/RAET1 molecules with transmembrane regions are ligands for NKG2D. J Immunol. 2004;173:1078–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cosman D, Mullberg J, Sutherland CL, Chin W, Armitage R, Farnslow W, Kubin M, Chalupny NJ. ULBPs, novel MHC class I related molecules, bind to CMV glycoprotein UL16 and stimulate NK cytotoxicity through the NKG2D receptor. Immunity. 2001;14:123–33. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welte SA, Sinzger C, Lutz SZ, Singh-Jasuja H, Sampaio KL, Eknigk U, Rammensee HG, Steinle A. Selective intracellular retention of virally induced NKG2D ligands by the human cytomegalovirus UL16 glycoprotein. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:194–203. doi: 10.1002/immu.200390022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunn C, Chalupny NJ, Sutherland CL, Dosch S, Sivakumar PV, Johnson DC, Cosman D. Human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein UL16 causes intracellular sequestration of NKG2D ligands, protecting against natural killer cell cytotoxicity. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1427–39. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vales-Gomez M, Browne H, Reyburn HT. Expression of the UL16 glycoprotein of human cytomegalovirus protects the virus-infected cell from attack by natural killer cells. BMC Immunol. 2003;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu J, Chalupny NJ, Manley TJ, Riddell SR, Cosman D, Spies T. Intracellular retention of the MHC class I-related chain B ligand of NKG2D by the human cytomegalovirus UL16 glycoprotein. J Immunol. 2003;170:4196–200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McFarland BJ, Strong RK. Thermodynamic analysis of degenerate recognition by the NKG2D immunoreceptor: not induced fit but rigid adaptation. Immunity. 2003;19:803–12. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carayannopoulos LN, Naidenko OV, Fremont DH, Yokoyama WM. Cutting edge: Murine UL16-binding protein-like transcript 1: a newly described transcript encoding a high-affinity ligand for murine NKG2D. J Immunol. 2002;169:4079–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Callaghan CA, Cerwenka A, Willcox BE, Lanier LL, Bjorkman PJ. Molecular competition for NKG2D. H60 and RAE1 compete unequally for NKG2D with dominance of H60. Immunity. 2001;15:201–11. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li P, Morris DL, Willcox BE, Steinle A, Spies T, Strong RK. Complex structure of the activating immunoreceptor NKG2D and its class I-like ligand MICA. Nature Immunol. 2001;2:443–51. doi: 10.1038/87757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carayannopoulos LN, Naidenko OV, Kinder J, Ho EL, Fremont DH, Yokoyama WM. Ligands for murine NKG2D display heterogeneous binding behavior. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:597–605. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200203)32:3<597::aid-immu597>3.3.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elsner HA, Schroeder M, Blasczyk R. The nucleotide diversity of MICA and MICB suggests the effect of overdominant selection. Tissue Antigens. 2001;58:419–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.580612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinle A, Li P, Morris DL, Groh V, Lanier LL, Strong RK, Spies T. Interactions of human NKG2D with its ligands MICA, MICB, and homologs of the mouse RAE-1 protein family. Immunogenetics. 2001;53:279–87. doi: 10.1007/s002510100325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caillat-Zucman S. How NKG2D ligands trigger autoimmunity? Hum Immunol. 2006;67:204–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pende D, Rivera P, Marcenaro S, et al. Major histocompatibility complex class I-related chain A and UL16-binding protein expression on tumor cell lines of different histotypes: analysis of tumor susceptibility to NKG2D-dependent natural killer cell cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6178–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poggi A, Venturino C, Catellani S, et al. Vδ1 T lymphocytes from B-CLL patients recognize ULBP3 expressed on leukemic B cells and up-regulated by trans-retinoic acid. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9172–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groh V, Rhinehart R, Secrist H, Bauer S, Grabstein KH, Spies T. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived gamma-delta T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6879–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu J, Groh V, Spies T. T cell antigen receptor engagement and specificity in the recognition of stress-inducible MHC class I-related chains by human epithelial gamma delta T cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:1236–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bauer S, Groh V, Wu J, Steinle A, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Spies T. Activation of natural killer cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science. 1999;285:727–30. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayakawa Y, Kelly JM, Westwood JA, Darcy PK, Diefenbach A, Raulet D, Smyth MJ. Cutting edge: Tumor rejection mediated by NKG2D receptor–ligand interaction is dependent upon perforin. J Immunol. 2002;169:5377–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conejo-Garcia JR, Benencia F, Courreges MC, et al. Letal, a tumor-associated NKG2D immunoreceptor ligand, induces activation and expansion of effector immune cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:446–51. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diefenbach A, Jamieson AM, Liu SD, Shastri N, Raulet DH. Ligands for the murine NKG2D receptor: expression by tumor cells and activation of NK cells and macrophages. Nature Immunol. 2000;1:119–26. doi: 10.1038/77793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cerwenka A, Bakker ABH, McClanahan T, Wagner J, Wu J, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. Retinoic acid early inducible genes define a ligand family for the activating NKG2D receptor in mice. Immunity. 2000;12:721–7. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pende D, Cantoni C, Rivera P, et al. Role of NKG2D in tumor cell lysis mediated by human NK cells: cooperation with natural cytotoxicity receptors and capability of recognizing tumors of nonepithelial origin. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1076–86. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1076::aid-immu1076>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oppenheim DE, Roberts SJ, Clarke SL, Filler R, Lewis JM, Tigelaar RE, Girardi M, Hayday AC. Sustained localized expression of ligand for the activating NKG2D receptor impairs natural cytotoxicity in vivo and reduces tumor immunosurveillance. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:928–37. doi: 10.1038/ni1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smyth MJ, Swann J, Cretney E, Zerafa N, Yokoyama WM, Hayakawa Y. NKG2D function protects the host from tumor initiation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:583–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiemann K, Mittrucker HW, Feger U, Welte SA, Yokoyama WM, Spies T, Rammensee HG, Steinle A. Systemic NKG2D down-regulation impairs NK and CD8 T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;175:720–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coudert JD, Zimmer J, Tomasello E, Cebecauer M, Colonna M, Vivier E, Held W. Altered NKG2D function in NK cells induced by chronic exposure to NKG2D-ligand expressing tumor cells. Blood. 2005;106:1711–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salih HR, Rammensee HG, Steinle A. Cutting edge: Down-regulation of MICA on human tumors by proteolytic shedding. J Immunol. 2002;169:4098–102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Groh V, Wu J, Yee C, Spies T. Tumour-derived soluble MIC ligands impair expression of NKG2D and T-cell activation. Nature. 2002;419:734–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salih HR, Goehlsdorf D, Steinle A. Release of MICB molecules by tumor cells: mechanism and soluble MICB in sera of cancer patients. Hum Immunol. 2006;67:188–95. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waldhauer I, Steinle A. Proteolytic release of soluble UL16-binding protein 2 from tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2520–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu JD, Higgins LM, Steinle A, Cosman D, Haugk K, Plymate SR. Prevalent expression of the immunostimulatory MHC class I chain-related molecule is counteracted by shedding in prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:560–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI22206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raffaghello L, Prigione I, Airoldi I, et al. Downregulation and/or release of NKG2D ligands as immune evasion strategy of human neuroblastoma. Neoplasia. 2004;6:558–68. doi: 10.1593/neo.04316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rolle A, Mousavi-Jazi M, Eriksson M, Odeberg J, Soderberg-Naucler C, Cosman D, Karre K, Cerboni C. Effects of human cytomegalovirus infection on ligands for the activating NKG2D receptor of NK cells: up-regulation of UL16-binding protein (ULBP) 1 and ULBP2 is counteracted by the viral UL16 protein. J Immunol. 2003;171:902–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nomura M, Zou Z, Joh T, Takihara Y, Matsuda Y, Shimada K. Genomic structures and characterization of RAE1 family members encoding GPI-anchored cell surface proteins and expressed predominantly in embryonic mouse brains. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1996;120:987–95. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Groh V, Bahram S, Bauer S, Herman A, Beauchamp M, Spies T. Cell stress-regulated human major histocompatibility complex class I gene expressed in gastrointestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12445–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zou Z, Nomura M, Takihara Y, Yasunaga T, Shimada K. Isolation and characterization of retinoic acid-inducible cDNA clones in F9 cells: a novel cDNA family encodes cell surface proteins sharing partial homology with MHC class I molecules. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1996;119:319–28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nowbakht P, Ionescu MC, Rohner A, et al. Ligands for natural killer cell-activating receptors are expressed upon the maturation of normal myelomonocytic cells but at low levels in acute myeloid leukemias. Blood. 2005;105:3615–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poggi A, Prevosto C, Massaro AM, et al. Interaction between human NK cells and bone marrow stromal cells induces NK cell triggering: role of NKp30 and NKG2D receptors. J Immunol. 2005;175:6352–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Becchetti S, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) /natural killer (NK) cell interactions: evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSC while MSC can inhibit IL-2-induced NK cell proliferation. Blood. 2005;107:1484–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ogasawara K, Benjamin J, Takaki R, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. Function of NKG2D in natural killer cell-mediated rejection of mouse bone marrow grafts. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:938–45. doi: 10.1038/ni1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li J, Rabinovich BA, Hurren R, Cosman D, Miller RG. Survival versus neglect: redefining thymocyte subsets based on expression of NKG2D ligand(s) and MHC class I. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:439–48. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jan Chalupny N, Sutherland CL, Lawrence WA, Rein-Weston A, Cosman D. ULBP4 is a novel ligand for human NKG2D. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:129–35. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00714-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Diefenbach A, Hsia JK, Hsiung MY, Raulet DH. A novel ligand for the NKG2D receptor activates NK cells and macrophages and induces tumor immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:381–91. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zwirner NW, Fernandez-Vina MA, Stastny P. MICA, a new polymorphic HLA-related antigen, is expressed mainly by keratinocytes, endothelial cells, and monocytes. Immunogenetics. 1998;47:139–48. doi: 10.1007/s002510050339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Molinero LL, Fuertes MB, Girart MV, Fainboim L, Rabinovich GA, Costas MA, Zwirner NW. NF-kappa B regulates expression of the MHC class I-related chain A gene in activated T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2004;173:5583–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rabinovich BA, Li J, Shannon J, Hurren R, Chalupny J, Cosman D, Miller RG. Activated, but not resting, T cells can be recognized and killed by syngeneic NK cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3572–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cerboni C, Zingoni A, Cippitelli M, Piccoli M, Frati L, Santoni A. Antigen-activated human T lymphocytes express cell surface NKG2D ligands via an ATM/ATR-dependent mechanism and become susceptible to autologous NK cell lysis. Blood. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-052720. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jinushi M, Takehara T, Kanto T, et al. Critical role of MHC class I-related chain A and B expression on IFN-alpha-stimulated dendritic cells in NK cell activation: impairment in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Immunol. 2003;170:1249–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nedvetzki S, Sowinski S, Eagle RA, et al. Reciprocal regulation of human natural killer cells and macrophages associated with distinct immune synapses. Blood. 2007;109:3776–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-052977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gasser S, Orsulic S, Brown EJ, Raulet DH. The DNA damage pathway regulates innate immune system ligands of the NKG2D receptor. Nature. 2005;436:1186–90. doi: 10.1038/nature03884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Routes JM, Ryan S, Morris K, Takaki R, Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Adenovirus serotype 5 E1A sensitizes tumor cells to NKG2D-dependent NK cell lysis and tumor rejection. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1477–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boissel N, Rea D, Tieng V, et al. BCR/ABL oncogene directly controls MHC class I chain-related molecule A expression in chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Immunol. 2006;176:5108–16. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.5108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nausch N, Florin L, Hartenstein B, Angel P, Schorpp-Kistner M, Cerwenka A. Cutting edge: The AP-1 subunit JunB determines NK cell-mediated target cell killing by regulation of the NKG2D-ligand RAE-1epsilon. J Immunol. 2006;176:7–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Eagle RA, Traherne JA, Ashiru O, Wills MR, Trowsdale J. Regulation of NKG2D ligand gene expression. Hum Immunol. 2006;67:159–69. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vankayalapati R, Garg A, Porgador A, et al. Role of NK cell-activating receptors and their ligands in the lysis of mononuclear phagocytes infected with an intracellular bacterium. J Immunol. 2005;175:4611–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tieng V, Le Bouguenec C, du Merle L, Bertheau P, Desreumaux P, Janin A, Charron D, Toubert A. Binding of Escherichia coli adhesin AfaE to CD55 triggers cell-surface expression of the MHC class I-related molecule MICA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2977–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032668099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Das H, Groh V, Kuijl C, Sugita M, Morita CT, Spies T, Bukowski JF. MICA engagement by human Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells enhances their antigen-dependent effector function. Immunity. 2001;15:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Groh V, Rhinehart R, Randolph-Habecker J, Topp MS, Riddell SR, Spies T. Costimulation of CD8alpha-beta T cells by NKG2D via engagement by MIC induced on virus-infected cells. Nature Immunol. 2001;2:255–60. doi: 10.1038/85321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Siren J, Sareneva T, Pirhonen J, Strengell M, Veckman V, Julkunen I, Matikainen S. Cytokine and contact-dependent activation of natural killer cells by influenza A or Sendai virus-infected macrophages. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2357–64. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yamamoto K, Fujiyama Y, Andoh A, Bamba T, Okabe H. Oxidative stress increases MICA and MICB gene expression in the human colon carcinoma cell line (CaCo-2) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1526:10–2. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tibbetts RS, Brumbaugh KM, Williams JM, et al. A role for ATR in the DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53. Genes Dev. 1999;13:152–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.2.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shiloh Y. ATM and ATR: networking cellular responses to DNA damage. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:71–7. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Armeanu S, Bitzer M, Lauer UM, et al. Natural killer cell-mediated lysis of hepatoma cells via specific induction of NKG2D ligands by the histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium valproate. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6321–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Groh V, Steinle A, Bauer S, Spies T. Recognition of stress-induced MHC molecules by intestinal epithelial gamma-delta T cells. Science. 1998;279:1737–40. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Venkataraman GM, Suciu D, Groh V, Boss JM, Spies T. Promoter region architecture and transcriptional regulation of the genes for the MHC class I-related chain A and B ligands of NKG2D. J Immunol. 2007;178:961–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lopez-Soto A, Quinones-Lombrana A, Lopez-Arbesu R, Lopez-Larrea C, Gonzalez S. Transcriptional regulation of ULBP1, a human ligand of the NKG2D receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30419–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Weitzman MD, Carson CT, Schwartz RA, Lilley CE. Interactions of viruses with the cellular DNA repair machinery. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bartek J, Lukas J. Chk1 and Chk2 kinases in checkpoint control and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:421–9. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]