Abstract

Complement is a major pro-inflammatory innate immune system whose serum activity correlates with systolic blood pressure in humans. To date, no studies using in vivo models have directly examined the role of individual complement components in regulating vessel function, hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy. Herein, in vivo responses to angiotensin (ang) II were characterized in mice deficient in CD59a or C3. CD59a–/– mice had slightly but significantly elevated systolic blood pressure (107·2 ± 1·7 mmHg versus 113·8 ± 1·31 mmHg, P < 0·01, for wild-type and CD59a–/–, respectively). Aortic rings from CD59a–/– mice showed significantly less platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) expression, with elevated deposition of membrane attack complex. However, acetylcholine- and sodium nitroprusside-dependent dilatation, plasma nitrate/nitrite and aortic cyclic guanosine monophosphate levels were unchanged from wild-type. Also, in vivo infusion with either ang II or noradrenaline caused similar hypertension and vascular hypertrophy to wild-type. Mice deficient in C3 had similar basal blood pressure to wild type and showed no differences in hypertension or hypertrophy responses to in vivo infusion with ang II. These data indicate that CD59a deficiency is associated with some vascular alterations that may represent early damage occurring as a result of increased complement attack. However, a direct role for CD59a or C3 in modulating development of ang II-dependent hypertension or hypertrophy in vivo is excluded and we suggest caution in development of complement intervention strategies for hypertension and heart failure.

Keywords: complement, CD59a, angiotensin, vascular, hypertension

Introduction

Many studies suggest an important role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of vascular disease and hypertension. However, what is often not clear is whether a particular inflammatory signalling pathway is a direct contributor to the disease or is simply a risk marker (e.g. consistently elevated but not actively participating). This distinction is important as millions of dollars is spent each year researching the therapeutic potential of blocking inflammatory pathways based on repeated observations of their activation in atherosclerosis or hypertension. A salient example of this is C-reactive protein (CRP), demonstrated as a predictor of myocardial infarction in numerous studies, including the Physicians' Health Study, Helsinki Heart Study, Women's Health Study, Iowa 65 + Rural Health Study, Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Study, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 11 A Trial and FRISK Trial.1–10 However, some investigators have cautioned that impurities such as endotoxin and sodium azide account for the in vitro effects of CRP, and recent studies using mice transgenic for human CRP have found that it is not pro-atherogenic in apolipoprotein E–/–.11–13

An important contributor to inflammation is the complement system which comprises serum proteins involved in host defence. Studies have suggested that complement may play a pathogenic role in hypertension, particularly that associated with elevated angiotensin (ang) II activity. Serum levels of C3 and C4 correlate with systolic blood pressure in humans.14,15 Additionally, studies demonstrating elevated C1q, C3, C3c and C5b-9 have suggested a role for complement in ang II-induced organ damage and smooth muscle proliferation in ang II-dependent hypertension.16,17 However, these studies are indirect, and do not address the question as to whether complement plays a direct pathogenic role in ang II signalling per se, using genetic models of complement deficiency. Making this distinction is important as discussed above, and so we examined ang II-dependent blood pressure (BP) and hypertrophy in mice deficient in C3 or CD59a, to determine their involvement in ang II responses in vivo and to delineate whether this pathway is an active participant or simply a risk marker of ang II-dependent vascular disease.14,15

Materials and methods

Materials

Rabbit anti-endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and rat anti-mouse platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) antisera were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA), goat anti-rat and anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) – Alexa 568 were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Rabbit anti-rat C9 cross-reactive with mouse C9 and membrane attack complex (MAC) was generated by immunizing rabbits with pure rat C9 as previously described.18 Unless otherwise stated, all compounds were from Sigma (Poole, UK).

Animal studies

All animal experiments were performed in accordance to the United Kingdom Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986. CD59a–/– or C3–/– mice on the C57Bl/6 background were generated as described previously.19,20 Age-matched wild-type male C57BL/6 mice (25–30 g) were obtained from Harlan (Oxford, UK). All mice were kept in constant temperature cages (20–22°) and given free access to water and standard chow.

Hypertension studies

Male 10–12-week-old wild-type, C3–/– or CD59a–/– mice were anaesthetized by inhalation of 2% isoflurane (98% oxygen). Osmotic minipumps (Alzet Model 1002, DURECT Corp, Cupertino, CA) containing ang II (1·1 mg/kg/day), NA (4 mg/kg/day), or vehicle, were implanted subcutaneously in the midscapular area. Systolic blood pressure (BP) was monitored daily for 2 days preimplantation (training period) and up to 7 days postimplantation via tail cuff plethysmography (World Precision Instruments, Stevenage, UK) in conscious mice.

Assessment of heart:body weight ratio, aortic medial area and immunohistochemistry

Seven days postimplantation, mice were killed by cervical dislocation and heart and body weights recorded. The descending thoracic aorta was removed, cleaned of adipose tissue and fixed in paraffin wax. For measurement of medial area, 15 µm sections were taken using a microtome, placed on glass slides, fixed using acetone, then stained with haematoxylin. Images were acquired using 5× air lens, with an Axiovert S100TV microscope and Hamamatsu Orca Digital Camera, and medial area calculated using Scion Image (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD). For each aorta, three separate sections were analysed and averaged. For immunohistochemistry, 10 µm sections were methanol-fixed on glass slides, permeabilized using 0·1% (w/v) Triton-X-100/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), blocked using 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin/PBS. MAC deposition was visualized using rabbit anti-rat C9 and goat anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa 568. PECAM-1 (CD31) expression was visualized using rabbit anti-PECAM-1 and goat anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa 568. AT1-R expression was visualized using rabbit anti-AT1-R (1:50, Santa Cruz), and goat anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa 568. Negative controls utilized equivalent concentrations of rabbit serum or isotype control IgG. Imaging was performed on an Axiovert 100 inverted microscope connected to a Bio-Rad MRC 1024ES laser scanning system (Bio-Rad Microscience, Hemel Hempstead, UK) and using standard analysis software (Lasersharp 2000, Bio-Rad Microscience). Images were acquired using a 10x air lens, with excitation at 568 nm and emission 595/35 nm. Quantification of protein expression was determined by averaging pixel intensity across the area of antigen expression using Lasersharp 2000. Each group consisted of four to five separate animals. For each animal, three separate aortic sections were quantified with three to four separate determinations per section. Post-acquisition processing was carried out using Adobe Photoshop.

Griess reaction for NO metabolites

The NO metabolites nitrate and nitrite (NOx) were determined using the Griess reaction.21 Briefly, whole blood was centrifuged to recover plasma, which was then centrifuged through a 10 000 MW filter (Microcon, Millipore, Bedford, MA) for 30 min. Filtrate was analysed for NOx by addition of sulphanilamide/HCl (1 mmol/l, 0·6 mol/l, respectively) and N-(1-naphtyl)-ethylenediamine (NEDA, 1 mmol/l), either with or without prior reduction using nitrate reductase (Aspergillus, Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) for 2 hr, 37°. Absorbances were measured at 530 nm and compared with standard curves generated using sodium nitrate or nitrite.

Radioimmunoassay of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)

Aortae were weighed, then homogenized in ice-cold trichloracetic acid (TCA) to give a final concentration of 10% TCA (w/v). Homogenates were centrifuged at 2000 g, then supernatants washed four times with 5 volumes of water-saturated diethyl ether. Aqueous extracts were dried then analysed for cGMP using a commercial radioimmunoassay kit (Biotrak, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Isometric tension functional studies

Male wild-type or CD59a–/– mice (25–30 g) were killed by cervical dislocation. The thoracic aorta was removed and placed in Krebs-Henseleit buffer (NaCl 120 mm; KCl 4·7 mm; MgSO4·7H2O 1·2 mm; NaHCO3 24 mm; KH2PO4 1·1 mm; glucose 10 mm; CaCl2·2H2O 2·5 mm). The aorta was dissected free of adipose tissue, taking care to retain adventitia, cut into rings (2–3 mm) and suspended in an isometric tension myograph (model 610: DMT, Aarhuis, Denmark) containing Krebs buffer at 37° and gassed with 5% CO2/95% O2. A resting tension of 3 mN was maintained, and changes in isometric tension recorded via Myodaq software (DMT). Following a 60 min equilibration period, vessels were primed with 48 mm KCl before a concentration (0·1 µm) of phenylephrine producing approximately 75% contraction was added. Once the response stabilized, 1 µm acetylcholine (ACh) was added to assess endothelial integrity. Any rings that did not maintain contraction, or relaxed <50% of the phenylephrine-induced tone were discarded. Then, the vessels were constricted to approximately 80% using 0·1 µm phenylephrine. Once a stable response to phenylephrine was observed, cumulative concentration–response curves were constructed to 1 nm−10 µm ACh and 1 nm−10 µm sodium nitroprusside (SNP) to assess endothelium-dependent and independent relaxations, respectively. Responses were expressed as a percentage of contracted tension (vasodilation). Responses from patent rings of each animal (two to four rings) were combined to produce an average for each sample (n). In some experiments, 300 µmN-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) was included in Ach dose–response experiments.

Results

Activation of complement and decreased expression of PECAM-1 in aortae of CD59a–/– mice

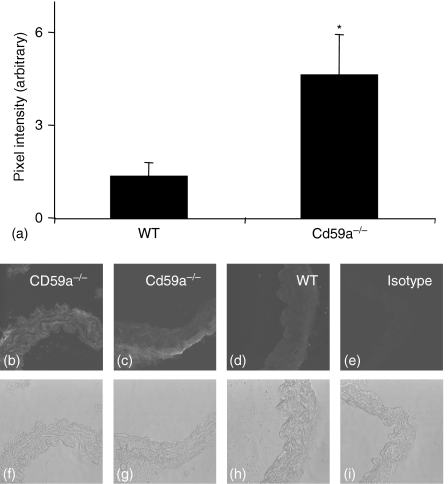

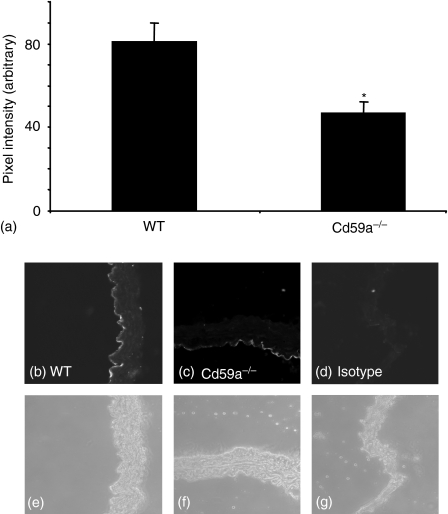

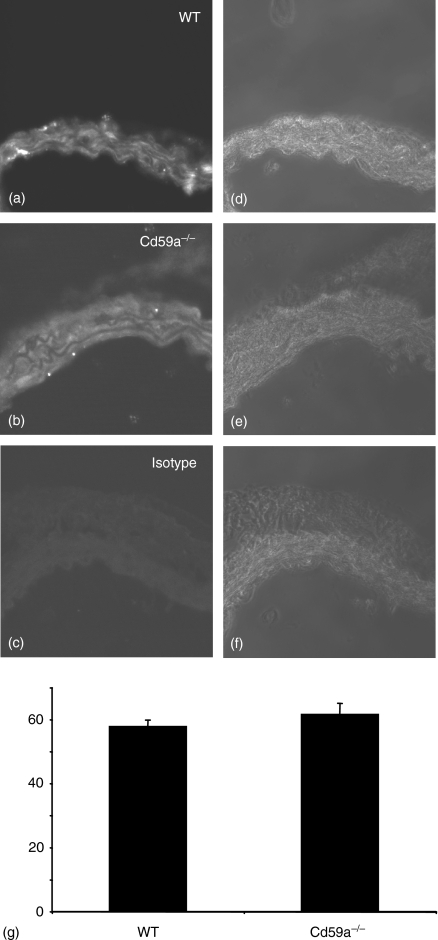

CD59a is the major inhibitor of complement activation in mice.22 To examine whether CD59a deficiency resulted in elevated complement attack in the vessel wall, we characterized deposition of MAC and expression of PECAM-1 in the thoracic aorta using immunohistochemistry. Because of the low levels of these proteins it is not possible to quantitate by Western blotting. Pixel intensity was measured at multiple sites in each section, using several sections per animal, as described in Methods. There was some small staining for C9 (a component of MAC) on wild type vessels, when compared to isotype control. However, MAC deposition was consistently and significantly increased in CD59a–/– vessels (Fig. 1b–i). Localization of MAC deposits in CD59a–/– vessels was variable, with expression either throughout the vessel wall (Fig. 1b), or in some animals colocalizing with outer layers of muscle and adventitia predominantly (Fig. 1c). Reasons for this variability are unclear but may be a characteristic of increased complement attack in vessels. Multiple pixel intensity determinations revealed approximately threefold elevations in staining for MAC in CD59a–/– aortae compared with wild-types (Fig. 1a). PECAM-1 staining revealed a clear endothelial localization in both wild type and CD59a–/–(Fig. 2b–g). However, expression of this protein was significantly decreased in CD59a–/– vessels, as revealed by pixel intensity determinations for endothelium (Fig. 2a). These data indicate that CD59a deficiency results in elevated vascular complement activity and some endothelial damage, as revealed by decreased PECAM-1 staining.

Figure 1.

C9 is elevated in aortae from CD59a–/– aortic rings. Aortic sections from wild type and CD59a–/– were sectioned and stained for C9, as described in Materials and methods. (a) Pixel intensity was determined following fluorescence staining of aortic sections as described in Materials and methods (n = 5 separate aortae, mean ± SEM, *P < 0·05, unpaired Student's t-test). Representative sections are shown for each condition. (b, c, f, g) CD59a–/–, (d, h). wild type, (e, i) isotype control antibody. (b–e) C9 fluorescence, (f–i). corresponding phase contrast images.

Figure 2.

PECAM-1 is decreased in aortae from CD59a–/– aortic rings. Aortic sections from wild type and CD59a–/– were sectioned and stained for PECAM-1, as described in Materials and methods. (a) Pixel intensity was determined following fluorescence staining of aortic sections as described in Materials and methods (n = 4 separate aortae, mean ± SEM, *P < 0·02, unpaired Student's t-test). Representative sections are shown for each condition. (b, e) wild type, (c, f) CD59a–/–, (d, g) isotype control antibody. (b, c, d) PECAM-1 fluorescence, (e, f, g) corresponding phase contrast images.

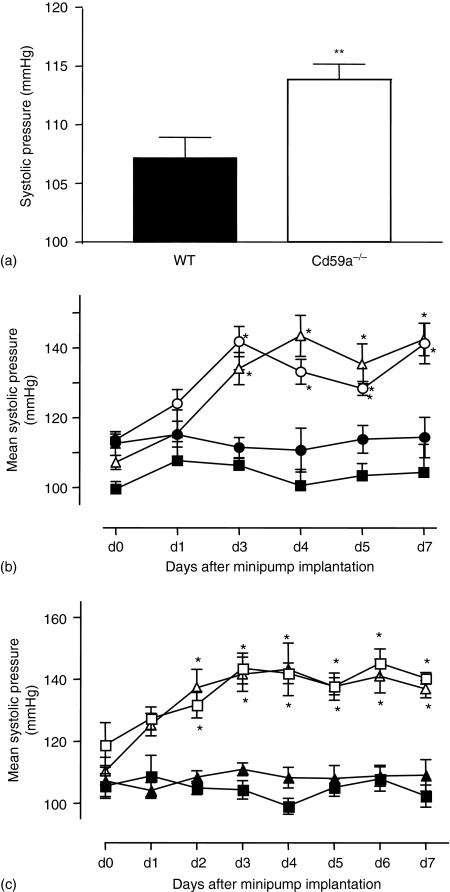

Blood pressure elevations in response to ang II are not altered in CD59a–/– or C3–/– mice

Basal BP of CD59a–/– mice was significantly higher than in wild type controls; however, the difference was only small (107·2 ± 1·7 mmHg, n = 23 versus 113·8 ± 1·31 mmHg, n = 16; P < 0·01, for wild type and CD59a–/–, respectively, mean ± SEM, Fig. 3a). Infusion of ang II (1·1 mg/kg/day) increased systolic BP in wild-type mice (Fig. 3b, c). Similarly, in CD59a–/– or C3–/– mice, ang II caused an increase in pressure, which was significantly different from baseline (Fig. 3b, c). Importantly, BP increases in complement-deficient strains were not significantly different from those of wild type ang II-infused mice (Fig. 3b, c). These data demonstrate that deletion of CD59a is associated with a small but significant increase in basal BP, but deletion of either CD59a or C3 resulted in no changes in induction of ang II-induced induced systolic hypertension.

Figure 3.

Basal systolic blood pressure is slightly elevated in CD59a–/– mice, although ang II-dependent elevations in systolic blood pressure are unchanged in CD59a–/– or C3–/– mice (a) Basal systolic blood pressure (total mean pressures) monitored as described in Methods using tail-cuff plethysmography was significantly higher in CD59a–/– mice (**P < 0·01 with respect to wild type (WT) mice). (b) Ang II (1·1 mg/kg/day) was infused into male 10–12-week-old WT or CD59a–/– mice by osmotic minipump as described in Methods. Systolic blood pressure (blood pressure) was monitored for 2 days preimplantation and 7 days postimplantation. (▪) WT, (▵) ang II-infused WT, (•) CD59a–/–, (○) ang II-infused CD59a–/– (n = 4–9 animals per group, mean ± SEM. (c) Ang II (1·1 mg/kg/day) was infused into male 10–12-week-old C3–/– or WT mice by osmotic minipump. Systolic blood pressure (blood pressure) was monitored for 2 days preimplantation and 7 days postimplantation. (▪) WT, (▴) C3–/–, (□) WT + ang II, (▵) C3–/–+ ang II (n = 6–8 animals per group, mean ± SEM, *P < 0·01 with respect to day 0; using anova test with Dunnett's post-hoc test to isolate differences).

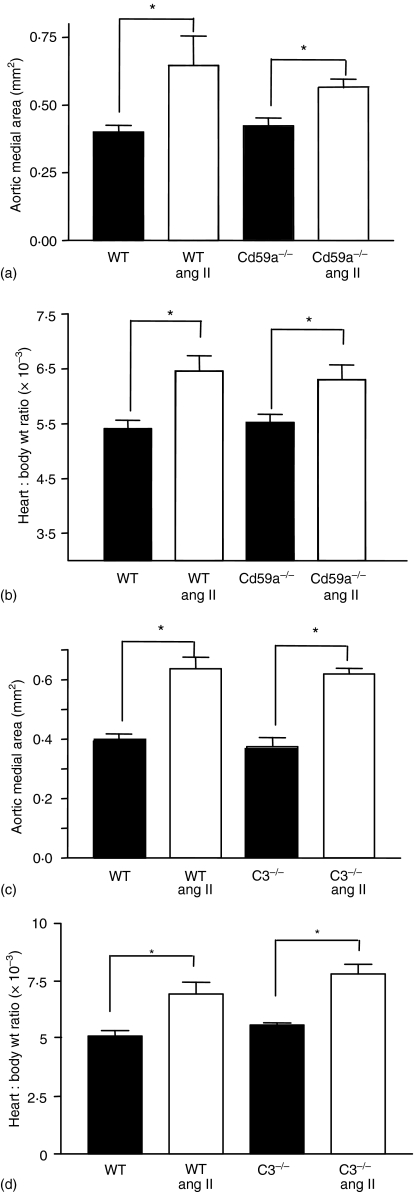

Ang II induces similar cardiac and aortic hypertrophy in wild type, CD59a–/– or C3–/– mice

Before ang II infusion, heart:body weight ratio and aortic medial area were similar for wild type, CD59a–/– or C3–/– mice (Fig. 4). Subcutaneous infusion of ang II caused similar increases in heart:body weight ratio and aortic medial area in all three strains (Fig. 4). These data demonstrate that CD59a or C3 expression does not influence heart size or vascular thickness, or ang II-induced cardiac and vascular hypertrophy in vivo.

Figure 4.

Development of ang II-induced vascular or cardiac hypertrophy is unchanged in CD59a–/– or C3–/– mice. Aortic sections were hematoxylin-stained and intima quantified as described in Materials and methods. (a) Aortic medial area was determined as described in Materials and methods, for wild type (WT) and CD59a–/– mice. For each aorta, 3 sections were analysed and averaged (n = 5 separate animals, mean ± SEM, *P < 0·05, with respect to wild type, or CD59a–/– group; unpaired Student's t-test). (b) Heart and body weight was recorded and compared before and after ang II-infusion (n = 4–5, mean ± SEM, *P < 0·05, with respect to wild type, or the CD59a–/– group; unpaired Student's t-test). (c) Aortic medial area was determined as described in (a), for WT and C3–/– mice. (n = 5 separate animals, mean ± SEM, *P < 0·05, with respect to wild type, or the CD59a–/– group; unpaired Student's t-test). (d) Heart and body weight was recorded and compared before and after ang II-infusion (n = 4–5, mean ± SEM, *P < 0·05, with respect to wild type, or the C3–/– group; unpaired Student's t-test).

Characterization of in vitro regulation of vessel tone, aortic cGMP, plasma NO metabolites and AT1-R expression in WT and CD59a–/– aortic rings

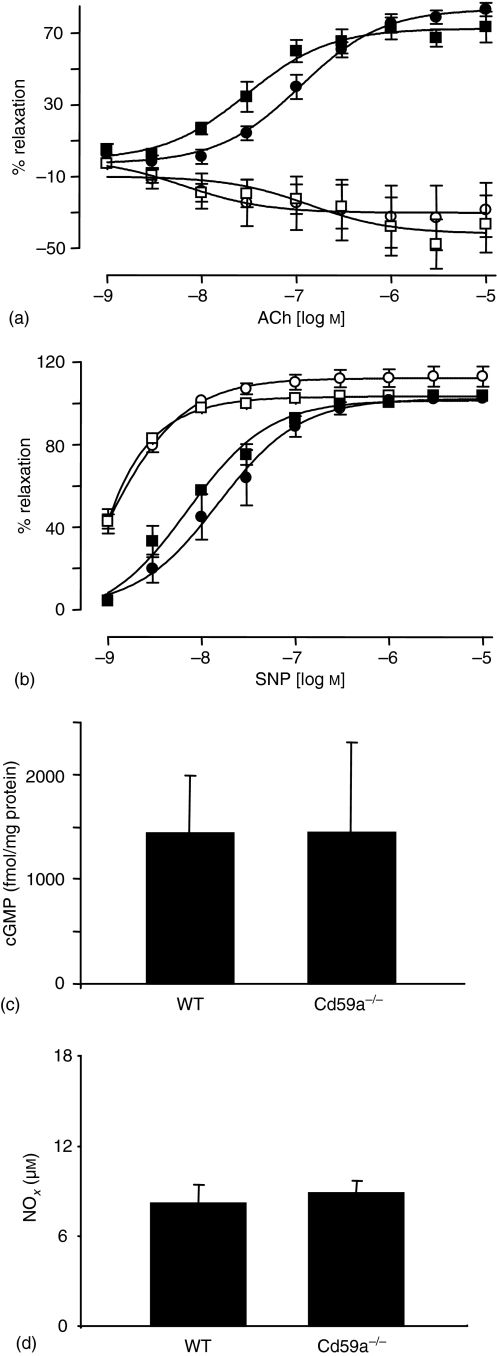

Basal systolic BP was slightly higher in CD59a–/– mice (Fig. 3a). Therefore, in vitro regulation of vessel tone and AT1-R expression was characterized in mice deficient in CD59a. To determine the influence of NO in regulation of tone, ACh and SNP responses of thoracic aortic rings were examined in the presence and absence of L-NAME, using standard myography techniques. There were no differences in the dose–response curves to ACh or SNP between wild type and CD59a–/– aortae (Fig. 5a, b). Additionally, inclusion of L-NAME abolished relaxation to ACh to a similar extent in both strains, while similarly sensitizing rings to SNP-mediated relaxation (Fig. 5a, b). Demonstration of identical responses to ACh and SNP indicate no changes to NO signalling between wild type and CD59a–/– mice. Furthermore, aortic cGMP and plasma nitrate/nitrite showed no significant differences between wild-type and CD59a–/– (Fig. 5c, d). This data indicates that NO bioactivity is unchanged with CD59a deficiency. To examine expression of AT1-R, sections of murine aorta were examined using immunohistochemistry. Clear vascular expression of AT1-R, particularly within the smooth muscle was apparent for wild type and CD59a–/– aorta. Quantification using pixel intensity showed identical levels of expression of AT1R for both strains (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Characterization of in vitro regulation of vessel tone in CD59a–/– aortic rings. Aortic ring functional responses were determined as described in Methods. (a) ACh-relaxation dose–response curves in wild-type or CD59a–/– rings (n = 2–5), with/without L-NAME (300 µm). (▪) WT, (□) WT + l-NAME, (•) CD59a–/–, (○) CD59a–/– + L-NAME. (b) Dose–response curves to SNP in wild type or CD59a–/– rings (n = 2–5), with/without L-NAME, (▪) WT, (□) WT + L-NAME, (•) CD59a–/–, (○) CD59a–/– + L-NAME. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. (c) cGMP levels were determined in aortic rings from CD59a–/– (n = 4) and wild type (n = 6) mice as described in Methods (mean ± SEM). (d) Nitrate/nitrite (NOx) levels in plasma from wild type (n = 6) or CD59a–/– (n = 4) mice were determined as described in Methods (mean ± SEM).

Figure 6.

Expression of AT1-R in aortae from wild type and CD59a–/– mice. Sections of mouse aorta were stained for AT1R as described in Materials and methods. (a–c) Fluorescence images of wild-type, CD59a–/– and isotype control, respectively. (d–f) Corresponding phase contrast images for (a–c). (g) Quantitation of AT1R expression in aortae (n = 12, mean ± SEM).

Discussion

MAC is frequently found in human atheromatous plaque, while elevated serum C3 and C4 correlate with human systolic blood pressure.14,15 Also, up-regulation of complement inhibitors, including CD59, by statins or CRP has suggested a protective role for these in preventing vascular injury. It must be stressed that the role of complement in vascular disease is still controversial because studies of atherosclerosis in animals deficient in several complement components have been contradictory.23–25 To determine the role of MAC formation and C3 inhibition in regulating vessel function and hypertension-associated vascular pathology, we evaluated control of vessel tone in vivo and in vitro in two murine strains with altered complement activity: (i) mice lacking CD59a, the primary regulator of MAC in mice, whose deficiency is associated with constitutively elevated MAC activation in vivo and (ii) mice lacking C3.19,22

Aortae from CD59a–/– mice had elevated vascular MAC deposition and decreased endothelial PECAM-1 (Figs 1 and 2). PECAM-1 is a transmembrane glycoprotein (CD31) that has important functions in inhibiting cell death. Decreased expression of PECAM-1 may indicate early damage to the vessel as a result of elevated complement attack. Basal BP was slightly elevated in CD59a–/– mice; however, in vitro studies showed regulation of vessel tone was largely normal, with most responses preserved as for wild type mice. In particular, ACh and SNP-dependent relaxation of isolated aortic rings, aortic cGMP and plasma nitrate/nitrite levels were all normal (Figs 5 and 6). These data indicate that the NO signalling pathway behaves normally in these mice, and that vessel changes have not yet progressed to reveal abnormal aortic functional responses. The reason(s) for elevated BP are unknown, but could involve changes in endogenous vasoconstrictors for example, endothelin, thromboxane or catecholamines.

In vivo infusion of ang II induced a similar degree of hypertension and vascular/cardiac hypertrophy in wild type, CD59a–/– and C3–/– mice (Fig. 3 and 4). These observations argue against either a protective role for CD59a or participation of C3 in the pathogenesis of ang II-dependent hypertension and hypertrophy. The data also suggest that a background of elevated vascular MAC activity does not promote the progression of ang II-dependent disease. Two recent studies have shown elevated complement activation products in rat models of ang II-induced disease, and the authors have suggested a pathogenic role in ang II-dependent pathologies. In one, elevations in C1q, C3, C3c, C5b-9 preceded ang II-dependent albuminuria.16 However, a direct causal role in mediating renal damage was not shown (e.g. using blockers of complement activation). In the second study microarray analysis of smooth muscle from spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats found elevated C3 expression and led to speculation that this might be the gene responsible for exaggerated smooth muscle growth, and therefore a new target for hypertension treatment.17 However, observations demonstrating elevations in specific pathways do not prove a pathogenic role, or address the in vivo relevance of their activation. Therefore, we studied mice genetically deficient in C3 and CD59, an approach that has not been used up to now to address their role in ang II disease. The studies would suggest that C3 and MAC are bystanders rather than participants, although extrapolation to human ang II-dependent vascular disease is guarded.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Wellcome Trust (V.B.O., BPM) is gratefully acknowledged. S.B. is a Wellcome Trust Travelling Fellow.

Abbreviations

- Ang

angiotensin

- BP

blood pressure

- l-NAME

N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester

- MAC

membrane attack complex

- NO

nitric oxide

- PECAM-1

platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

References

- 1.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH. Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000;101:1767–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.15.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Pfeffer MA, Sacks FM, Moye LA, Goldman S, Flaker GC, Braunwald E. Inflammation, pravastatin, and the risk of coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) Investigators. Circulation. 1998;98:839–44. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.9.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Roitman-Johnson B, Stampfer MJ, Allen J. Plasma concentration of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and risks of future myocardial infarction in apparently healthy men. Lancet. 1998;351:88–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:836–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ridker PM, Glynn RJ, Hennekens CH. C-reactive protein adds to the predictive value of total and HDL cholesterol in determining risk of first myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;97:2007–11. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.20.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roivainen M, Viik-Kajander M, Palosuo T, et al. Infections, inflammation, and the risk of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2000;101:252–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, et al. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am J Med. 1999;106:506–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrow DA, Rifai N, Antman EM, Weiner DL, McCabe CH, Cannon CP, Braunwald E. C-reactive protein is a potent predictor of mortality independently of and in combination with troponin T in acute coronary syndromes: a TIMI 11A substudy. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1460–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindmark E, Diderholm E, Wallentin L, Siegbahn A. Relationship between interleukin 6 and mortality in patients with unstable coronary artery disease: effects of an early invasive or noninvasive strategy. Jama. 2001;286:2107–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.17.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindahl B, Toss H, Siegbahn A, Venge P, Wallentin L. Markers of myocardial damage and inflammation in relation to long-term mortality in unstable coronary artery disease. FRISC Study Group. Fragmin during Instability in Coronary Artery Disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1139–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010193431602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor KE, Giddings JC, van den Berg CW. C-reactive protein-induced in vitro endothelial cell activation is an artefact caused by azide and lipopolysaccharide. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1225–30. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000164623.41250.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oroszlan M, Herczenik E, Rugonfalvi-Kiss S, et al. Proinflammatory changes in human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells can be induced neither by native nor by modified CRP. Int Immunol. 2006;18:871–8. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lafuente N, Azcutia V, Matesanz N, Cercas E, Rodriguez-Manas L, Sanchez-Ferrer CF, Peiro C. Evidence for sodium azide as an artifact mediating the modulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase by C-reactive protein. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005;45:193–6. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000154371.95907.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muscari A, Massarelli G, Bastagli L, Poggiopollini G, Tomassetti V, Volta U, Puddu GM, Puddu P. Relationship between serum C3 levels and traditional risk factors for myocardial infarction. Acta Cardiol. 1998;53:345–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomaszewski M, Zukowska-Szczechowska E, Grzeszczak W. [Evaluation of complement component C4 concentration and immunoglobulins IgA, IgG, and IgM in serum of patients with primary essential hypertension] Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2000;103:247–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shagdarsuren E, Wellner M, Braesen JH, et al. Complement activation in angiotensin II-induced organ damage. Circ Res. 2005;97:716–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000182677.89816.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin ZH, Fukuda N, Jin XQ, et al. Complement 3 is involved in the synthetic phenotype and exaggerated growth of vascular smooth muscle cells from spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2004;44:42–7. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000129540.83284.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones J, Laffafian I, Morgan BP. Purification of C8 and C9 from rat serum. Complement Inflamm. 1990;7:42–51. doi: 10.1159/000463125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt DS, Botto M, Bygrave AE, Hanna SM, Walport MJ, Morgan BP. Targeted deletion of the CD59 gene causes spontaneous intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2001;98:442–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.2.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wessels MR, Butko P, Ma M, Warren HB, Lage AL, Carroll MC. Studies of group B streptococcal infection in mice deficient in complement component C3 or C4 demonstrate an essential role for complement in both innate and acquired immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11490–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt H, Kelm M. Determination of nitrite and nitrate by the Griess reaction. In: Stamler F, Feelisch M, editors. Methods in Nitric Oxide Research. London: Wiley; 1996. pp. 491–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baalasubramanian S, Harris CL, Donev RM, Mizuno M, Omidvar N, Song WC, Morgan BP. CD59a is the primary regulator of membrane attack complex assembly in the mouse. J Immunol. 2004;173:3684–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmiedt W, Kinscherf R, Deigner HP, et al. Complement C6 deficiency protects against diet-induced atherosclerosis in rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1790–5. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.11.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel S, Thelander EM, Hernandez M, et al. ApoE (–/–) mice develop atherosclerosis in the absence of complement component C5. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:164–70. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buono C, Come CE, Witztum JL, Maguire GF, Connelly PW, Carroll M, Lichtman AH. Influence of C3 deficiency on atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:3025–31. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000019584.04929.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]