Abstract

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the primary cause of bronchiolitis in young children. Upon infection both T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 cytokines are produced. Because RSV-induced Th2 responses have been associated with severe immunopathology and aggravation of allergic reactions, the regulation of the immune response following RSV infection is crucial. In this study we examined the influence of RSV on the activation and function of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (DCs). RSV induced the expression of maturation markers on myeloid DCs (mDCs) in vitro. The mDCs stimulated with RSV and ovalbumin (OVA) enhanced proliferation of OVA-specific T cells, which produced both Th1 and Th2 cytokines. In contrast to mDCs, RSV did not induce the expression of maturation markers on plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), not did it enhance the proliferation of OVA-specific T cells that were cocultured with pDCs. However, RSV stimulated the production of interferon-α (IFN-α) by pDCs. Our findings indicate a clear difference in the functional activation of DC subsets. RSV-stimulated mDCs may have immunostimulatory effects on both Th1 and Th2 responses, while RSV-stimulated pDCs have direct antiviral activity through the release of IFN-α.

Keywords: allergy, dendritic cells, flow cytometry, lung immunology/disease, respiratory syncytial virus

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection is the primary cause of pneumonia and bronchiolitis in young children. By the age of 2 years RSV has infected about 90% of all infants and young children, and about 2% of these infections results in hospitalization.1 Upon RSV infection a strong T helper 1 (Th1) response is induced. However, a severe RSV infection may be associated with a shift towards a Th2 response.2,3 Recently, Hoebee et al. found a genetic association between the interleukin-4 (IL-4) locus and severe RSV infection, providing further evidence for the involvement of the Th2 pathway in severe RSV infection.4 However, other studies failed to find confirmation of a more pronounced Th2 immune response in infants with severe RSV infection.5 In mice a primary RSV infection results in a predominant Th1-type immune response characterized by high levels of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and relatively low levels of IL-4 mRNA expression in the lung.6

Some aspects of severe RSV-associated pathology resemble asthma. The immune pathology of asthma is characterized by a Th2 immune response, including an influx of eosinophils and production of IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13 by T cells.2,7 Studies have also been performed to investigate the role of RSV in the development of asthma in children, but epidemiological studies so far report controversial results.8–10 In mice, RSV infection aggravated allergic respiratory disease by enhancing particular Th2 cytokine responses.6 Therefore the regulation of the immune response following RSV infection, in particular the Th1/Th2 ratio, appears crucial in determining both the outcome of infection and the influence of infection on allergic responses.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells and may modulate the Th1/Th2 balance upon antigen exposure by producing specific cytokines.11 Hence we decided to study their role in the onset and regulation of T-cell-mediated immune responses following RSV infection. In the lungs, DCs lie directly underneath the mucosal epithelium of the airways and are probably the primary antigen-presenting cell involved in detecting and presenting the antigens of respiratory viruses.

Two major subtypes of DCs, myeloid DCs (mDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), have been distinguished. Both mDCs and pDCs are involved in the immune mechanisms in the lung. For example, mDCs exposed to influenza virus induced a Th1 response to influenza when used to immunize BALB/c mice.12 However, when mDCs encountered non-infectious inhaled antigens, they induced Th2-dominated sensitization leading to eosinophilic airway inflammation.13 It may be that pDCs have a role in mounting a protective immune response to virus infections by producing large amounts of IFN-α, which has both antiviral and immunoregulatory activities. Activation of pDCs by pathogens has also been reported to profoundly promote Th1 immune responses and to suppress Th2 immune responses.14

The exact role of DCs in the response to RSV still needs to be elucidated. Because responses to RSV may include both Th1 and Th2 responses, we hypothesized that RSV has different effects on mDCs and pDCs that may therefore differentially influence the balance between Th1/Th2 cells. We therefore examined the influence of RSV on maturation, cytokine production, and antigen-presenting capacity of both mDCs and pDCs. This antigen-presenting capacity was determined by studying the proliferation and cytokine production of ovalbumin (OVA)-specific T cells that were stimulated by OVA-pulsed and RSV-exposed DCs.

Materials and methods

Virus

Human RSV type A2 (RSV A2) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). The virus was cultured on Hep-2 cells (ATCC) in medium (RPMI-1640, Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) containing, 2 mm glutamine, 100 IE/ml penicillin and 100 U/ml streptomycin. After 77 hr of culture, cells were harvested and centrifuged for 10 min at 1000 g at 4°. The supernatant was collected and snap-frozen in aliquots, which were stored at − 80°. The infectivity of the virus stock (1·2 × 107 plaque-forming units RSV/ml) was assessed by quantitative plaque-forming assay.15,16 The supernatant of an uninfected Hep-2 cell culture was used as a mock control.

To inactivate RSV, the original stock was divided into small subsamples and irradiated with UV light (302 nm, dose 1·5 × 10−2 μW/mm2, Transilluminator, ultra-violet products, San Gabriel, CA) for 45 min.17

Animals

All experiments were performed using 6- to 12-week-old female BALB/c (H-2d) mice (Harlan, Zeist, the Netherlands) and ovalbumin-specific, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-restricted, T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice (DO11.10; NVI, Bilthoven, the Netherlands). Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at the animal care facility at the Netherlands Vaccine Institute (NVI). All experimental procedures used in this study were approved by the National institute for public health and the environment (RIVM) committee for animal experiments.

Collection of cells

Myeloid dendritic cells

Bone marrow cells were collected from naive mice by flushing femurs and tibiae with 5 ml sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The mDCs were generated by stimulating bone marrow with granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) as described.18 Briefly, after red blood cell lysis, bone marrow cells were resuspended at 2 × 105 cells/ml in DC culture medium [DC-CM; RPMI-1640 containing glutamax-I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 50μmβ-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 50 μg/ml gentamycin (Gibco) and 20 ng/ml recombinant mouse GM-CSF (a kind gift from Prof K. Thielemans, VUB, Brussels, Belgium)] and 5 × 105 cells/well were seeded in a six-well plate (day 0). On day 3, 2 ml fresh DC-CM was added. On days 6 and 8, 2 ml from each well was centrifuged and resuspended in 2 ml fresh DC-CM. On day 8, cells were pulsed with lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-free OVA (LPS, < 20 pg/mg protein; Seikagaku, Tokyo, Japan) and stimulated with RSV for 24 hr or 48 hr with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. As controls, cells were stimulated with UV-inactivated RSV (UV-RSV), or mock, or LPS (500 ng/ml).

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells

Cells were cultured using fresh bone marrow from naive mice. Cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells/ml supplemented with Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (FLT3-L, 200 ng/ml) and 10 × 106 cells/well were seeded in bacterial Petri dishes. On day 4 the FLT3-L-culture cells were collected and replated in bacterial Petri dishes at 1 × 106 cells/ml and supplemented with FLT3-L (200 ng/ml). On day 8 FLT3-L-culture cells were purified under sterile conditions on a FACS ARIA flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). The FLT3-L culture was stained as described below and pDCs were defined and sorted as 120G8high, B220high, CD11blow, CD11cint.19 After cell sorting the percentage of pDCs was 98%. Sorted cells were resuspended at 1·5 × 105 cells/ml per well in DC culture medium and were seeded in 24-well plate. Cells were pulsed with LPS-free OVA (LPS < 20 pg/mg protein; Seikagaku) and stimulated with RSV for 24 hr (MOI 10). Stimulation with UV-RSV, mock or CpG [ISS-ODN 1668, tcc atg acg ttc ctg atg ct (Sigma-genosys)] were used as a control.

Lymph nodes

Cell suspensions were made from pooled peripheral lymph nodes isolated from OVA323−339-specific, MHC class II-restricted, TCR-transgenic (DO11.10) mice. These cells were labelled with the mitosis-sensitive dye carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) molecular probes (Eugene, OR) as previously described20 and 5 × 104 cells/well were cocultured in a 96-well plate together with OVA-stimulated and RSV-stimulated DCs (5 × 103 cells/well). After 96 hr, cells were harvested and T-cell proliferation and cytokine production were analysed.

Cytokine measurements

Levels of IL-10 and IL-12p70 in culture supernatants were measured using OptEIA kits (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. IFN-α in culture supernatants was measured using an IFN-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA kit; ebioscience, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and IL-6 concentration was assessed by ELISA according to the protocol described by Boelen et al.15 The culture supernatants of the DC/T-cell cocultures were tested for multiple cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13 and IFN-γ) using the Lumina-based Bio-Plex system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Flow cytometry

The effects of RSV stimulation on the expression of costimulatory and adhesion molecules on DCs were measured using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. Cells were stained in PBS containing 5% FCS and 5 mm sodium azide (FACSwash) using monoclonal antibodies directed against the following antigens: 120G8 labelled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (a kind gift from Carine Asselin-Paturel, Laboratory for Immunological Research, Schering-Plough Research Institute, Dardilly, France), CD11c labelled with allophycocyanin, and CD40, CD80, CD86 and MHC class II labelled with phycoerythrin. To reduce non-specific antibody binding, anti-FcγRII antibody (2.4G2, ATCC, Manassas, VA) was included in all cell-surface stainings. Propidium iodide (Sigma Aldrich) was used to determine the viability of the cells. (Other cells were excluded in analysis by gating for DCs.)

To recognize OVA-specific TCR-transgenic CD4+ T cells, the cells were labelled with αCD4-allophycocyanin in combination with the anticlonotypic DO11.10-TCR antibody KJ1-26 conjugated to phycoerythrin, which was obtained from Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Dead cells were excluded by labelling with propidium iodide before acquisition. To examine the number of cell divisions, T cells were labelled with CFSE. The division index was defined as the average number of divisions that a cell from the starting population had undergone.

All fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences; 5 × 104 to 1·5 × 106 events were acquired on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and were analysed with Flowjo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least in triplicate. Cytokine data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test (Excel, Microsoft Corporation Redmond). P-values less than 0·05 were considered significant.

Results

The influence of RSV on maturation and functional activation of mDCs

First the response of bone marrow-derived mDCs upon RSV inoculation was studied. In pilot dose–response experiments in which the cells were stained for the expression of maturation markers, we established the optimal amount of virus at an MOI of 10. RSV stimulation for 48 hr at an MOI of 10 induced a consistent up-regulation of maturation markers, while RSV stimulation for 24 hr induced only a minimal and inconsistent up-regulation. Incubation of mDCs with RSV did not lead to a decrease in viability of these cells (data not shown).

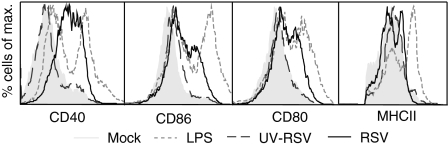

On day 8 of culture mDCs were inoculated with RSV or with equal amounts of UV-RSV or mock control. After 48 hr of stimulation RSV enhanced the expression of CD40, CD80 and CD86 on mDCs in comparison with mock (Fig. 1). To examine the influence of virus replication on mDC activation, we inoculated the cells with UV-RSV, which, in contrast to live RSV, was not able to induce up-regulation of the analysed maturation markers (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Maturation of mDCs by RSV. Expression of MHC class II, CD40, CD80 and CD86 on murine bone marrow-derived mDCs was determined after stimulation for 48 hr with RSV (black line), UV-RSV (dark grey striped line), LPS (light grey striped line), or as a negative control, mock (shaded histogram). The experiment was carried out three times; one representative experiment is depicted.

Subsequently, we examined whether RSV-activated mDCs produced IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70 and IFN-α 48 hr after stimulation. However RSV was not able to induce production of any of these cytokines by mDCs (data not shown).

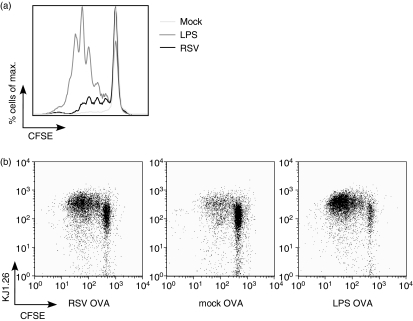

Next we examined whether RSV enhanced the capacity of OVA-pulsed mDCs to induce the proliferation of OVA-specific T cells. After a coculture of 96 hr the cells were harvested and the division index of the OVA-specific T cells was determined by measuring their CFSE dilution profile. T cells stimulated by RSV- and OVA-treated mDCs induced proliferation of OVA-specific T cells with a division index of 0·21, in comparison with 0·05 for T cells stimulated with mock-treated and OVA-treated mDCs, or with 0·75 for T cells stimulated with LPS-treated and OVA-treated mDCs (Fig. 2a,b). When mDCs were stimulated with RSV alone they were not able to induce T-cell proliferation. (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Proliferation of T cells stimulated with RSV-pulsed and OVA-pulsed mDCs. T cells were obtained from mice that were transgenic for the OVA T-cell receptor (CD4+ OVA TCR Tg T cells). CFSE-labelled T cells were cocultured with mDCs that were pulsed with RSV and OVA, LPS and OVA, or mock and OVA. After 96 hr cells were collected and CFSE+ CD4+ OVA TCR Tg T cell proliferation was analysed and is represented as a histogram (a) and a dot plot analysis (b). The experiment was performed three times; one representative experiment is depicted.

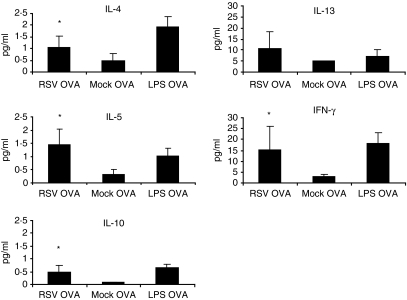

We next analysed the production of cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13 and IFN-γ in the supernatant of the DC-T-cell cocultures. In comparison with the mock control, coculture of RSV-treated and OVA-treated mDCs and OVA-specific T cells resulted in a statistically significant (P < 0·05) enhanced production of IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IFN-γ(Fig. 3). As expected, LPS-treated and OVA-treated DCs induced the highest level of the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ. However this treatment also induced large amounts of IL-13.

Figure 3.

Cytokine production of T cells stimulated with RSV-pulsed and OVA-pulsed mDCs. T cells were cocultured with mDCs that were pulsed with RSV and OVA, LPS and OVA, or mock and OVA. After 96 hr cytokine concentrations were examined by a multiplex bead assay. Mean values ± standard deviation (n = 5) are depicted. Statistical differences between T cells stimulated with mDCs pulsed with RSV and OVA, and T cells stimulated with mDCs pulsed with mock and OVA are indicated by *P < 0·05.

The influence of RSV on maturation and functional activation of pDCs

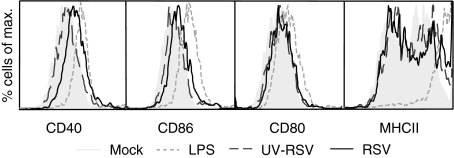

Besides the influence of RSV on mDCs, we examined the response of pDCs upon RSV stimulation. The pDCs were purified from a FLT3-L-stimulated bone marrow culture by flow cytometry and were defined as 120G8high, B220high, CD11blow and CD11cint cells. Because the viability of the pDC culture decreased over time after inoculation with RSV (data not shown), we stimulated pDCs for 24 hr. During that period RSV was unable to up-regulate the expression of any of the maturation markers CD86, CD80 and MHC class II on pDCs and only slightly up-regulated CD40 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Lack of maturation of pDCs by RSV. Expression of MHC class II, CD40, CD80 and CD86 on pDCs was determined after stimulation for 24 hr with RSV (black line), UV-RSV (dark grey striped line), LPS (light grey striped line), or as a negative control, mock (shaded histogram). The experiment was performed three times; one representative experiment is depicted.

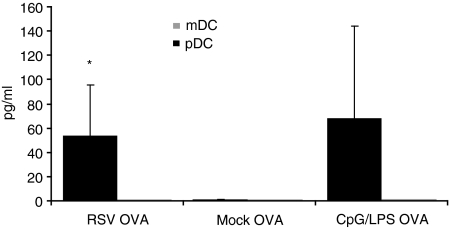

Similarly, RSV was unable to induce the production of IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12p70 by pDCs. However, RSV strongly enhanced IFN-α production by pDCs in comparison to mock-stimulated pDCs (P < 0·05). In contrast to RSV, UV-RSV was not able to induce IFN-α production in pDCs, indicating the relevance of virus replication. As mentioned above, mDCs were unable to produce IFN-α after 48 hr of RSV stimulation (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

IFN-α production by pDCs exposed to RSV. The mDCs (grey) and pDCs (black) were exposed to RSV. After 24 hr IFN-α production was assessed by ELISA. Mean values ± standard deviation (n = 5) are depicted. Statistical differences are indicated by *P < 0·05.

Subsequently, we examined the ability of stimulated pDCs to induce proliferation of OVA-specific T cells. However RSV-treated and OVA-treated pDCs did not induce proliferation of OVA-specific T cells after 24 hr as shown by a division index of 0·03, which is not above baseline level. CPG-treated and OVA-treated pDCs were also unable to induce proliferation of OVA-specific T cells (data not shown). Similarly, RSV and OVA-treated pDCs were not able to induce IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13 and IFN-γ production by T cells (data not shown).

Discussion

Different types of DCs may play different roles in the onset of a Th1 or Th2 immune response and in the induction of allergy.13,14,21 We studied the influence of RSV on the maturation and antigen-presenting capacity of DCs using OVA as an allergen.

RSV induced up-regulation of the maturation markers CD40, CD80 and CD86 on murine mDCs. These findings are in agreement with the results of studies using human monocyte-derived DCs.22,23 Up-regulated expression of maturation markers on mDCs occurred after 48 hr of RSV stimulation. This long stimulation period may suggest that replication of RSV is necessary to induce maturation of mDCs, which is supported by our finding that UV-inactivated RSV is unable to up-regulate the analysed markers. Interestingly, Kondo et al. demonstrated RSV replication in murine mDCs by detecting viral RNA after 24 hr of RSV stimulation.24 Assuming a lag period between RSV replication and up-regulation of maturation marker expression, the data of Kondo et al. concur with our data.

Although we observed up-regulation of maturation markers, RSV-stimulated mDCs did not produce IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12p70. This finding indicates activation of the mDC via a MyD88-independent pathway, which is characterized by a lack of cytokine production in the presence of up-regulated expression of maturation markers.25 In contrast, MyD88-dependent activation results in expression of maturation markers and production of cytokines.25,26

Next, the influence of RSV on the capacity of DCs to stimulate and polarize allergen-specific T cells in vitro was examined. Murine models of allergen-induced pulmonary inflammation share many features with human asthma, including the development of antigen-induced pulmonary eosinophilia and the production of Th2 cytokines. Since OVA is the most widely used antigen to induce eosinophilic airway inflammation,27 we used OVA in our study to asses the role of RSV on the antigen-presenting capacity of DCs. Enhanced T-cell proliferation is seen after coculture of T cells with RSV-treated and OVA-treated mDCs, but not after coculture with UV-RSV-treated and OVA-treated mDCs. This enhanced T-cell proliferation is most likely the result of the enhanced expression of the costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80 and CD86 on the mDCs. The significance of these costimulatory molecules is illustrated by the observation that mice deficient in B7.1 (CD80) and B7.2 (CD86) were severely impaired in their effector T-cell induction.28 Others also showed an impaired effector T-cell development using CD80/CD86–/– DCs, which however, did induce T-cell proliferation.29

Thus, RSV stimulated the antigen-presenting capacity of murine mDCs resulting in enhanced proliferation of OVA-specific T cells. In contrast, in vitro experiments using human monocytes showed an inhibitory effect of RSV on LPS-induced T-cell proliferation.22,23 Whether this discrepancy is related to differences in culture methods or study design needs to be determined. The heterologous infection used in our work and the use of OVA as a bystander antigen may have resulted in a different activation route in the DCs. Also, a species-specific suppressive effect of the viral fusion protein on T-cell activity was recently shown.30

In addition to T-cell proliferation, the balance between Th1 and Th2 cells is important and may determine the outcome of an immune response towards infection and allergy. We showed that RSV-pulsed and OVA-pulsed mDCs induced the production of both Th1 and Th2 cytokines by T cells, i.e. IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and IFN-γ. The lack of a clear Th polarization is most likely caused by failure of RSV to induce production of Th1 (IL-12) or Th2 (IL-10)-polarizing cytokines in DCs.

In contrast to mDCs, RSV was unable to induce the up-regulation of maturation markers on pDCs. RSV was also unable to enhance the antigen-presenting capacity of pDCs, as shown by a lack of enhanced proliferation and cytokine production by OVA-specific T cells. These data are in agreement with those of Wang et al. who also showed that RSV-infected pDCs were not able to induce antigen-specific T-cell proliferation.31 However, these authors found up-regulation of CD80 and CD86 on pDCs induced by RSV, which is in contrast to our findings. This discrepancy may be related to differences in study design. Although we observed a minimal up-regulation of the maturation markers on mDCs after a stimulation period with RSV for 24 hr, we cannot totally exclude the possibility that the observed differences between mDCs and pDCs are somewhat influenced by different stimulation times. However, a longer stimulation period with RSV resulted in a dramatic decrease in viability of pDCs.

Even though no up-regulation of maturation markers on pDCs was observed, RSV-stimulated pDCs did produce IFN-α, which is in agreement with other results.22,31 This is the major difference we observed between mDCs and pDCs upon stimulation with RSV. Our data suggest an important role for the production of IFN-α produced by pDCs in the immune response against RSV. In mouse models RSV infection was exacerbated in STAT1 and IFNαβγR knockout mice.32,33 Administration of IFN-α, or poly (IC), a potent IFN-α inducer, significantly enhanced the clearance of RSV even in pDC-depleted mice.34

We speculate that the observed differences between mDCs and pDCs are caused by their use of different pathogen recognition molecules on these cells. Pathogens are detected by TLRs, which are differently expressed by the different human DC types.35,36 Human mDCs express TLR4, while pDCs express TLR7.35,37 RSV is specifically recognized by TLR4, which binds the viral fusion protein F.38,39 IFN-α production by pDCs in our study might have been triggered by TLR7. This TLR has been shown to produce IFN-α after binding viral genomic single-stranded RNA.40–42 Interestingly, TLR4 is expressed extracellularly and TLR7 is expressed on endosomes.43,44 Future work should confirm whether the observed differences in the activity of RSV on mDCs and pDCs are really caused by different use of TLRs. Evidently DCs may also have been triggered by a TLR-independent route.

In conclusion, our data suggest that there is a clear difference in functional activation between mDCs and pDCs during RSV infection. RSV enhanced the functional maturation of mDCs and their capacity to induce adaptive T-cell responses. RSV-stimulated pDCs provide an early source of IFN-α necessary for limiting viral replication. However, RSV-stimulated pDCs do not seem to activate T-cell responses, at least to bystander antigens. Thus mDCs may enhance both beneficial and pathological immune responses, while pDCs may exert direct antiviral activity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank H. Strootman, J. van de Siepkamp and W. Vos for their assistance with the animal experiments. I. Boogaard is funded by ZonMw – Health Research and Development Counsil.

Abbreviations

- CFSE

carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- DC

dendritic cell

- DC-CD

dendritic cell culture medium

- FACS

fluorescent-activated cell sorting

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- FLT3-L

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand

- GM-CSF

granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- mDC

myeloid DC

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- NVI

Netherlands Vaccine Institute

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- pDC

plasmacytoid DC

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- Th1

T helper 1

- Th2

T helper 2

- UV-RSV

ultraviolet-inactivated RSV

References

- 1.Collins C. Fields Virology. Philadelphia: Raven Publishers; 2001. Murphy. Respiratory Syncytial Virus; pp. 1443–85. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roman M, Calhoun WJ, Hinton KL, Avendano LF, Simon V, Escobar AM, Gaggero A, Diaz PV. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants is associated with predominant Th-2-like response. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:190–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.1.9611050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendelja K, Gagro A, Bace A, Lokar-Kolbas R, Krsulovic-Hresic V, Drazenovic V, Mlinaric-Galinovic G, Rabatic S. Predominant type-2 response in infants with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection demonstrated by cytokine flow cytometry. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121:332–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoebee B, Rietveld E, Bont L, et al. Association of severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis with interleukin-4 and interleukin-4 receptor alpha polymorphisms. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:2–11. doi: 10.1086/345859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandenburg AH, Kleinjan A, van Het Land B, et al. Type 1-like immune response is found in children with respiratory syncytial virus infection regardless of clinical severity. J Med Virol. 2000;62:267–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barends M, Boelen A, de Rond L, Kwakkel J, Bestebroer T, Dormans J, Neijens H, Kimman T. Influence of respiratory syncytial virus infection on cytokine and inflammatory responses in allergic mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:463–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuipers H, Lambrecht BN. The interplay of dendritic cells, Th2 cells and regulatory T cells in asthma. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:702–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein RT, Sherrill D, Morgan WJ, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Taussig LM, Wright AL, Martinez FD. Respiratory syncytial virus in early life and risk of wheeze and allergy by age 13 years. Lancet. 1999;354:541–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sigurs N, Bjarnason R, Sigurbergsson F, Kjellman B. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy is an important risk factor for asthma and allergy at age 7. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1501–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9906076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigurs N, Gustafsson PM, Bjarnason R, Lundberg F, Schmidt S, Sigurbergsson F, Kjellman B. Severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy and asthma and allergy at age 13. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:137–41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-730OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalinski P, Hilkens CM, Wierenga EA, Kapsenberg ML. T-cell priming by type-1 and type-2 polarized dendritic cells: the concept of a third signal. Immunol Today. 1999;20:561–7. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez CB, Fernandez-Sesma A, Schulman JL, Moran TM. Myeloid dendritic cells stimulate both Th1 and Th2 immune responses depending on the nature of the antigen. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2001;21:763–73. doi: 10.1089/107999001753124499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambrecht BN, De Veerman M, Coyle AJ, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Thielemans K, Pauwels RA. Myeloid dendritic cells induce Th2 responses to inhaled antigen, leading to eosinophilic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:551–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI8107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlender J, Hornung V, Finke S, et al. Inhibition of toll-like receptor 7- and 9-mediated alpha/beta interferon production in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells by respiratory syncytial virus and measles virus. J Virol. 2005;79:5507–15. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5507-5515.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boelen A, Andeweg A, Kwakkel J, Lokhorst W, Bestebroer T, Dormans J, Kimman T. Both immunisation with a formalin-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine and a mock antigen vaccine induce severe lung pathology and a Th2 cytokine profile in RSV-challenged mice. Vaccine. 2000;19:982–91. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waris M, Ziegler T, Kivivirta M, Ruuskanen O. Rapid detection of respiratory syncytial virus and influenza A virus in cell cultures by immunoperoxidase staining with monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1159–62. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1159-1162.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Binnendijk RS, van Baalen CA, Poelen MC, de Vries P, Boes J, Cerundolo V, Osterhaus AD, UytdeHaag FG. Measles virus transmembrane fusion protein synthesized de novo or presented in immunostimulating complexes is endogenously processed for HLA class I- and class II-restricted cytotoxic T cell recognition. J Exp Med. 1992;176:119–28. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, Rossner S, Koch F, Romani N, Schuler G. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Meth. 1999;223:77–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asselin-Paturel C, Brizard G, Pin JJ, Briere F, Trinchieri G. Mouse strain differences in plasmacytoid dendritic cell frequency and function revealed by a novel monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 2003;171:6466–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambrecht BN, Pauwels RA, Fazekas De St Groth B. Induction of rapid T cell activation, division, and recirculation by intratracheal injection of dendritic cells in a TCR transgenic model. J Immunol. 2000;164:2937–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Heer HJ, Hammad H, Soullie T, Hijdra D, Vos N, Willart MA, Hoogsteden HC, Lambrecht BN. Essential role of lung plasmacytoid dendritic cells in preventing asthmatic reactions to harmless inhaled antigen. J Exp Med. 2004;200:89–98. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guerrero-Plata A, Casola A, Suarez GYuX, Spetch L, Peeples ME, Garofalo RP. Differential response of dendritic cells to human metapneumovirus and respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:320–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0287OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Graaff PM, de Jong EC, van Capel TM, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of monocyte-derived dendritic cells decreases their capacity to activate CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:5904–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondo Y, Matsuse H, Machida I, et al. Regulation of mite allergen-pulsed murine dendritic cells by respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:494–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200305-663OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:135–45. doi: 10.1038/35100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Hoshino K, Akira S. Endotoxin-induced maturation of MyD88-deficient dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5688–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Rijt LS, Lambrecht BN. Role of dendritic cells and Th2 lymphocytes in asthma: lessons from eosinophilic airway inflammation in the mouse. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;53:256–72. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borriello F, Sethna MP, Boyd SD, et al. B7-1 and B7-2 have overlapping, critical roles in immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity. 1997;6:303–13. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Rijt LS, Vos N, Willart M, Kleinjan A, Coyle AJ, Hoogsteden HC, Lambrecht BN. Essential role of dendritic cell CD80/CD86 costimulation in the induction, but not reactivation, of TH2 effector responses in a mouse model of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:166–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlender J, Walliser G, Fricke J, Conzelmann KK. Respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein mediates inhibition of mitogen-induced T-cell proliferation by contact. J Virol. 2002;76:1163–70. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1163-1170.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Peters N, Schwarze J. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells limit viral replication, pulmonary inflammation, and airway hyperresponsiveness in respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Immunol. 2006;177:6263–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson TR, Mertz SE, Gitiban N, Hammond S, Legallo R, Durbin RK, Durbin JE. Role for innate IFNs in determining respiratory syncytial virus immunopathology. J Immunol. 2005;174:7234–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hashimoto K, Durbin JE, Zhou W, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in the absence of STAT 1 results in airway dysfunction, airway mucus, and augmented IL-17 levels. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:550–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smit JJ, Rudd BD, Lukacs NW. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells inhibit pulmonary immunopathology and promote clearance of respiratory syncytial virus. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1153–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadowaki N, Ho S, Antonenko S, Malefyt RW, Kastelein RA, Bazan F, Liu YJ. Subsets of human dendritic cell precursors express different toll-like receptors and respond to different microbial antigens. J Exp Med. 2001;194:863–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards AD, Diebold SS, Slack EM, Tomizawa H, Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Toll-like receptor expression in murine DC subsets: lack of TLR7 expression by CD8 alpha+ DC correlates with unresponsiveness to imidazoquinolines. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:827–33. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visintin A, Mazzoni A, Spitzer JH, Wyllie DH, Dower SK, Segal DM. Regulation of Toll-like receptors in human monocytes and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:249–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurt-Jones EA, Popova L, Kwinn L, et al. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:398–401. doi: 10.1038/80833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haynes LM, Moore DD, Kurt-Jones EA, Finberg RW, Anderson LJ, Tripp RA. Involvement of toll-like receptor 4 in innate immunity to respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol. 2001;75:10730–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10730-10737.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303:1529–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibson SJ, Lindh JM, Riter TR, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells produce cytokines and mature in response to the TLR7 agonists, imiquimod and resiquimod. Cell Immunol. 2002;218:74–86. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00517-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuchsberger M, Hochrein H, O'Keeffe M. Activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83:571–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]