Abstract

Using T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice, we demonstrate that TCR stimulation of naive CD4+ T cells induces transient T-bet expression, interleukin (IL)-12 receptor β2 up-regulation, and GATA-3 down-regulation, which leads to T helper (Th)1 differentiation even when the cells are stimulated with peptide-loaded I-Ab-transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells in the absence of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and IL-12. Sustained IFN-γ and IL-12 stimulation augments naive T-cell differentiation into Th1 cells. Intriguingly, a significant Th1 response is observed even when T-bet–/– naive CD4+ T cells are stimulated through TCR in the absence of IFN-γ or IL-12. Stimulation of naive CD4+ T cells in the absence of IFN-γ or IL-12 with altered peptide ligand, whose avidity to the TCR is lower than that of original peptide, fails to up-regulate transient T-bet expression, sustains GATA-3 expression, and induces differentiation into Th2 cells. These results support the notion that direct interaction between TCR and peptide-loaded antigen-presenting cells, even in the absence of T-bet expression and costimulatory signals, primarily determine the fate of naive CD4+ T cells to Th1 cells.

Keywords: helper T cells (Th cells, Th0, Th1, Th2, Th3); MHC–peptide interactions; T-cell receptor (TCR); transcription factors/gene regulation

Introduction

The helper T cell is responsible for orchestrating an appropriate immune response against a wide variety of pathogens. Naive CD4+ T cells recognize antigenic peptide in context of class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and subsequently differentiate into effector T helper (Th) cells. CD4+ Th cells are classified into two subsets of Th cells, Th1 and Th2.1,2 Th1 cells secrete interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-2, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and TNF-β, and are responsible for cell-mediated immunity and the eradication of intracellular pathogens. Th1 cells are also involved in transplant rejection, and protection from neoplasms.3 Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, these cytokines are crucial for optimal antibody production, and are essential for the effective elimination of extracellular organisms, such as helminths and nematodes.3 Excessive production of Th1-type cytokines has been associated with the tissue destruction found in various autoimmune diseases, whereas over production of Th2-type cytokines have been implicated in atopy and allergic asthma. Therefore, elucidation of the mechanisms involved in the activation of naive CD4+ T cells and differentiation of the T cells into each Th subset is of central importance in understanding immune regulation. Our knowledge of Th cell biology has increased substantially over the past two decades4 but the molecular mechanisms regulating the initiation of either a Th1 or Th2 response remain incompletely understood.

The CD4+ T-cell differentiation process is initiated when the T-cell receptor (TCR) on a naive Th cell encounters its cognate antigen, which is bound to MHC class II molecules on APC. The stimulus delivered via the TCR, in conjunction with activation of costimulatory pathways, is essential for the progression of Th cell differentiation. Upon TCR engagement a number of factors influence the differentiation process toward the Th1 or Th2 lineage, including the type of APC, the concentration of antigen (duration and strength of signal), the ligation of costimulatory molecules, and the local cytokine environment.5–7 The most clearly defined factors determining Th subset differentiation from naive CD4+ T cells are cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-12 present at the initiation of the immune response both during and after the TCR ligation. Using mice deficient for signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), it has been shown that activation of the IL-12 receptor (R)/STAT4 signalling pathway is important for the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Th1 subset.8,9 In contrast, the IL-4R/STAT6 signalling pathway plays a central role in the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Th2 subset.10–12 Determination of Th cell differentiation is also regulated by changes in the chromatin structure surrounding the Th cytokine genes, ifn-γ and il-4/il-13.13

The activation of naive CD4+ T cells requires two separate signals. The TCR/CD3 complex delivers the first signal after its interaction with MHC peptide complex on APC. Several studies claim that the potency of TCR signalling regulates the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Th1 and Th2 subsets. Stimulation with high affinity peptides and high antigen dose favours Th1 differentiation and stimulation with low affinity peptides and low antigen dose favours Th2 differentiation.14–16 However, it is still controversial whether TCR signals play a critical role in the fate of Th cell differentiation. The second signal is costimulatory, and acts through several accessory molecules on the APC that interact with their ligands on T cells such as CD28-CD80/CD86, CD152 (cytolytic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4)–CD80/CD86, CD134 (OX40)–CD252 (OX40 ligand), CD278 (inducible costimulator)–CD275 (B7h), and CD11a (leucocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1))–CD54 (intracellular adhesion molecule-1).17–23

A critical stage in the differentiation process naive to Th1 CD4+ T cells occurs with the induction of a transcription factor, T-bet.24,25 T-bet is a ‘master regulator’ of Th1 differentiation through the up-regulation of IFN-γ and suppression of Th2-associated cytokine expression. In CD4+ T cells, T-bet is rapidly and specifically induced in developing Th1 cells but not Th2 cells. T-bet expression appears to be controlled by both the TCR and the IFN-γR/STAT1 signal transduction pathways.26,27 A regulatory circuit involving IFN-γR signalling maintains, via STAT1, a high-level T-bet expression in developing Th1 cells.26,27 Thus, T-bet mediates STAT1-dependent processes involved in Th1 development. T-bet also induces IL-12Rβ2 expression27,28 allowing IL-12/STAT4 signalling to optimize IFN-γ production, thereby completing the Th1 developmental commitment process. From these studies it is still unclear whether TCR signals enable T-bet to specify commitment towards Th1, IL-12Rβ2 expression and primary IFN-γ production, or whether TCR signals act to stabilize pre-existing Th1/Th2 commitment decisions.

Ag85B elicits a strong Th1 response in vitro in T cells both from purified protein derivatives-positive asymptomatic human subjects and Ag85B-primed cells of C57BL/6 (I-Ab) mice. Peptide-25 (aa240–254 FQDAYNAAGGHNAVF) of Ag85B is a major epitope recognized by Th1 cells. Active immunization of C57BL/6 mice with Peptide-25 induces the differentiation of CD4+ TCR Vβ11+ T cells into Th1 cells.29–32 To elucidate molecular mechanisms of Th1 differentiation and examine the role of TCR signalling on T-bet expression, we analysed T-bet expression in naive CD4+ T cells of TCR transgenic mice (P25 TCR-Tg) that recognize Peptide-25 in conjunction with I-Ab. Here we present evidence that indicates that direct interaction between TCR and Peptide-25-loaded APC directly determines the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells towards the Th1 subset without T-bet expression, cytokine costimulation or surface bound molecular costimulation.

Materials and methods

Mice

P25 TCR-Tg mice were generated as previously described.33 C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Japan SLC Inc. (Hamamatsu, Japan). RAG-2–/– mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and backcrossed five times with C57BL/6 mice. IFN-γ–/– mice (C57BL/6 background) were kindly provided by Dr Y. Iwakura (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan). T-bet–/– mice34 were kindly provided by Dr L. H. Glimcher (Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA), and were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice more than six generations. IL-12/IL-18–/– mice35 (C57BL/6 background) were kindly provided by Dr K. Nakanishi (Hyogo College of Medicine, Nishinomiya, Japan). STAT1–/– mice (C57BL/6 Background) were kindly provided by Dr R. D. Schreiber (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO). P25 TCR-Tg mice were bred to RAG-2–/–, IFN-γ–/–, STAT1–/– or T-bet–/– mice. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in our animal facility according to our Institute's guideline, and used at 8–15 weeks of age.

Reagents and antibodies

Peptide-25 (FQDAYNAAGGHNAVF), and altered peptide ligand (APL) (G248A: FQDAYNAAAGHNAVF) were synthesized by Funakoshi Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Contamination of lipopolysaccharide in peptide preparations was undetectable (< 0·05 EU/ml), assessed by EndosafeR-PTS (Japanese Charles River Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Anti-IFN-γ–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; XMG1.2), anti-IL-4-allophycocyanin (11B11), anti-Vβ11–phycoerythrin (PE; RR3-15), anti-CD3ε–FITC (145-2C11), anti-CD4–FITC or –PE(GK1.5), anti-CD25–FITC (7D4), anti-CD28–FITC (37.51), anti-CD44–PE (IM7), anti-CD62 ligand (L)–FITC (MEL-14), anti-CD69–FITC (H1.2F3) and anti-LFA−1-FITC (2D7) were purchased from BD Bioscience PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Purified anti-CD3ε, anti-IFN-γ (R4-6A2) and anti-IL-12 (C17.8) were purchased from BD Bioscience PharMingen. IL-4 was purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Preparation of naive CD4+ T cells and APC

Splenic CD4+ T cells from P25 TCR-Tg or wild type (WT) C57BL/6 mice were enriched by using BDTM IMag mouse CD4 T lymphocyte enrichment system (BD Bioscience PharMingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. CD44low CD62Lhigh CD4+ T cells were purified from splenic CD4+ T cells by sorting with FACSAria (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) after staining with anti-CD44–PE and anti-CD62L–FITC and were used as naive CD4+ T cells. The purity of naive cells was > 99%.

Splenocytes from WT or IL-12/IL-18–/– mice were labelled with a mixture of biotin anti-Thy1.2, biotin anti-DX5 and streptavidin particle-DM (BD Bioscience PharMingen) to deplete T cells and natural killer (NK) cells. Cells were then recovered by magnetic separation. Recovered cells were irradiated with a total of 3500 rad, and used as APCs. Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing I-Ab (I-Ab-CHO) (kindly provided by Dr Y. Fukui, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan) were incubated with peptides for 12 hr, extensively washed and incubated with 50 µg/ml of mitomycin C for 15 min at 37° and used as APCs.

In vitro culture of CD4+ T cells

For cell culture throughout the present experiments, complete medium consisting of RPMI-1640 with 8% fetal calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), 50 µm 2-mercaptoethanol, 50 IU/ml of penicillin and 50 µg/ml of streptomycin was used.

To examine Th differentiation in vitro, two-step cultures were employed. For the first culture, purified naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 105 cells/ml) were activated for 6 days with peptides in the presence of T cell- and NK cell-depleted APC (2·5 × 106 cell/ml) or with peptide-loaded I-Ab-CHO cells (2·5 × 105 cells/ml) in a 48-well plate. IL-12 (10 ng/ml) and anti-IL-4 (10 µg/ml) were added to the culture to create Th1-skewing conditions, IL-4 (5 ng/ml), anti-IFN-γ (10 µg/ml) and anti-IL-12 (10 µg/ml) were added to create Th2-skewing conditions, or there was no addition of exogenous cytokines or antibodies, hereafter referred to as non-skewing conditions. In some experiments, purified naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with 10 µg/ml of soluble anti-CD3 in the presence of T cell- and NK-cell depleted APC. For the second culture, the cells collected from the first culture were washed, and the viable primed CD4+ T cells were re-stimulated with 1 µg/well of plate-coated anti-CD3.

Intracellular cytokine staining and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis

Cytokine-producing cells were identified by cytoplasmic staining with anti-cytokine antibodies as previously described.36 Briefly, the stimulated cells were stained for Vβ11 or CD4, fixed, permeabilized and stained for IFN-γ and IL-4. The cells stained were gated on live Vβ11- or CD4-positive cells and analysed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson). The percentages of IL-4- and IFN-γ-producing cells are presented in the upper left and the lower right regions of Figs 1–3, 5, respectively.

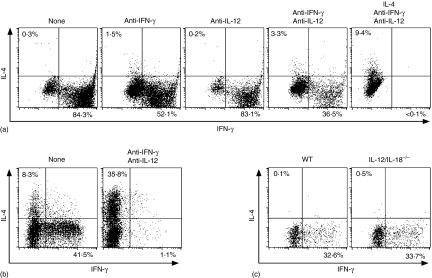

Figure 1.

Th1 differentiation of P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells upon Peptide-25 stimulation is independent on IFN-γ, IL-12 and IL-18. (a) Naive CD4+ T cells from RAG-2–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were stimulated in vitro with 10 µg/ml of Peptide-25 for 6 days in the presence of splenic APC. On day 0, some groups of culture received anti-IFN-γ, anti-IL-12, IL-4 or a combination of these, as depicted in (a). After the culture the primed cells were re-stimulated and IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were assessed. Events shown are gated on live Vβ11+ cells. Results are presented for one of three experiments performed, with similar results in each experiment. (b) Naive CD4+ T cells from WT C57BL/6 were stimulated in vitro with 10 µg/ml of soluble anti-CD3 in the presence of splenic APC. On day 0, a group of culture received anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL12. After the culture the primed cells were re-stimulated and IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were assessed. Events shown are gated on live CD4+ cells. Representative results of two separate experiments were displayed. (c) P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated in vitro with 10 µg/ml of Peptide-25 in the presence of splenic APC from WT or IL-12/IL-18–/– mice. After the culture the primed cells were re-stimulated and IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were assessed. Events shown are gated on live Vβ11+ cells. Representative results of two separate experiments were displayed.

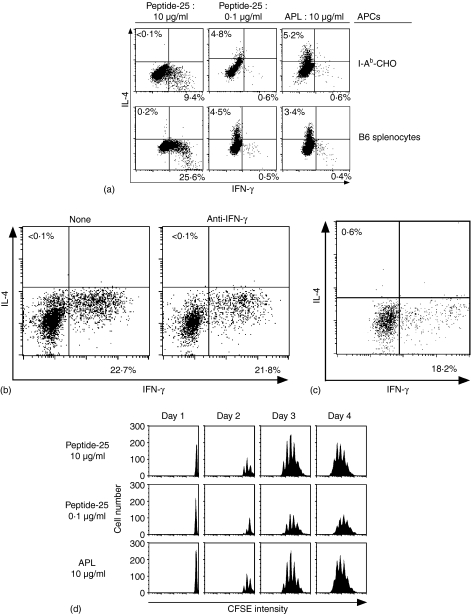

Figure 3.

Th1 differentiation of P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells can be induced in Peptide-25-loaded antigen-presenting cells lacking nominal costimulatory molecules. (a) P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated in vitro with 10 µg/ml or 0·1 µg/ml of Peptide-25 or 10 µg/ml of APL in the presence of I-Ab-CHO or splenic APC. After the culture the primed cells were re-stimulated and IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were assessed. Events shown are gated on live Vβ11+ cells. Representative results of three separate experiments were displayed. (b) Naive CD4+ T cells from P25 TCR-Tg were stimulated in vitro with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO in the presence or absence of anti-IFN-γ. After the culture the primed cells were re-stimulated and IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were assessed. Events shown are gated on live Vβ11+ cells. Results are presented for one of three experiments performed, with similar results in each experiment. (c) Naive CD4+ T cells from STAT1–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were stimulated in vitro with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO. After the culture the primed cells were re-stimulated and IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were assessed. Events shown are gated on live Vβ11+ cells. Results are presented for one of three experiments performed, with similar results in each experiment. (d) Naive CD4+ T cells from P25 TCR-Tg mice were labeled with 5 µm of CFSE and stimulated with 10 µg/ml or 0·1 µg/ml of Peptide-25 or 10 µg/ml of APL in the presence of splenic APC. On the days indicated, CD4+ T cells were harvested, stained for CD4 and Vβ11, and then analysed for dilution of CFSE intensity by FACSCalibur. Events shown are gated on live CD4+− Vβ11+ cells.

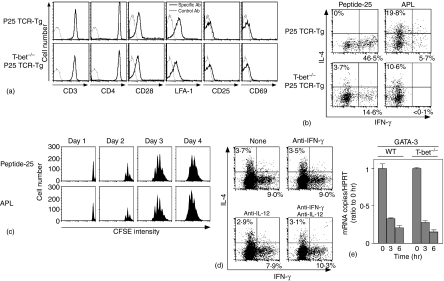

Figure 5.

Induction of GATA-3 transcripts is down-regulated in Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO-stimulated T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg naive T cells. (a) Naive CD4+ T cells from P25 TCR-Tg or T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were stained for CD3, CD4, CD28, LFA-1, CD25 and CD69. Events shown were gated on live cells. (b) Naive CD4+ T cells from P25 TCR-Tg or T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were stimulated in vitro with 10 µg/ml of Peptide-25 in the presence of splenic APC under non-skewing conditions. After the culture the primed cells were re-stimulated and IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were assessed. Events shown are gated on live Vβ11+ cells. Representative results of four separate experiments were displayed. (c) Naive CD4+ T cells from T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were labelled with CFSE and stimulated with 10 µg/ml of Peptide-25 or 10 µg/ml of APL in the presence of splenic APC. On the days indicated, CD4+ T cells were harvested, stained for CD4 and Vβ11, and analysed for dilution of CFSE intensity by FACSCalibur. Events shown are gated on live CD4 ± Vβ11+ cells. (d) Naive CD4+ T cells from T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were stimulated with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO. On day 0, some groups of culture received anti-IFN-γ, anti-IL-12 or a combination of these, as depicted in (d). After the culture the primed cells were re-stimulated and IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were assessed. Events shown are gated on live Vβ11+ cells. Results are presented for one of three experiments performed, with similar results in each experiment. (e) Naive CD4+ T cells from P25 TCR-Tg or T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were stimulated for indicated periods of time (hr) with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO. Cells were collected at the indicated time points and RNA was extracted. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed for assessing the mRNA expression of GATA-3 and HPRT. Each sample was normalized to HPRT. Data shown are ratios of test mRNA copies to mRNA copies of unstimulated cells. The values represent the mean and SD. Representative results of three separate experiments were displayed.

To examine expression of cell surface molecules on naive CD4+ T cells, purified CD4+ T cells were stained with antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD25, CD28, CD69, or LFA-1. The cells stained were gated on live cells and analysed on a FACSCalibur.

Proliferation assay

Division cycle number of CD4+ T cells was determined according to procedures previously described.37 Purified naive CD4+ T cells from P25 TCR-Tg mice were suspended in RPMI-1640 at 1 × 107 cells/ml and incubated with 5 µm of 5-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at room temperature for 15 min. The labelled CD4+ T cells were washed with culture medium and then cultured with peptide in the presence of T cell- and NK cell-depleted APC for various periods of time. After the culture, the cells recovered were stained for CD4 and Vβ11, and then suspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% fetal calf serum, 0·05% sodium azide and 2 µg/ml 7-amino-actinomycin D (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) to exclude dead cells from the analysis. Analyses of cell division cycle number among viable cells were conducted using FACSCalibur.

Quantitative fluorogenic real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

For quantitative fluorogenic PCR experiments, real-time LightCycler PCR system (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) with FastStart Master Hybridization Probe (Roche Diagnostics) was used. After extracting RNA from primary or secondary stimulated cells with RNeasy (QIAGEN Inc. Valencia, CA), cDNA was reverse transcribed with 0·5 µg of Oligo(dT)12–18 and Superscript III (Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, CA) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Primers and probes were hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl-transferase (HPRT) sense primer, 5′-GTT AAG CAG TAC AGC CCC AA-3′, HPRT antisense primer, 5′-TCA AGG GCA TAT CCA ACA AC-3′, HPRT probes, 5′-TCC AAC AAA GTC TGG CCT GTA TCC AA-FITC-3′, 5′-LC Red640-ACT TCG AGA GGT CCT TTT CAC CAG CA-3′; IL-12Rβ2 sense primer, 5′-GGC ATT TAC TCT CCT GTC-3′, IL-12Rβ2 antisense primer, 5′-GAG ATT ATC CGT AGG TAG C-3′ IL-12Rβ2 probes, 5′-CAA TGG TAT AGC AGA ACC ATT CCA GAT C-FITC-3′, 5′-LC Red640-AGC AAA CAG CAC TTG GGT AAA GAA GTA TC-3′; T-bet sense primer, 5′-CCT CTT CTA TCC AAC CAG TAT C-3′, T-bet antisense primer, 5′-CTC CGC TTC ATA ACT GTG T-3′, T-bet probes, 5′-CAT ATC CTT GGG CTG GCC TGG AAG-FITC-3′, 5′-LC Red640-TCG GGG TAG AAA CGG CTG GGA A-3′; GATA-3 sense primer, 5′-GAA GGC ATC CAG ACC CGA AAC-3′, GATA-3 antisense primer, 5-ACC CAT GGC GGT GAC CAT GC-3′, GATA-3 probes, 5′-AGC TGC TCT TGG GGA AGT CCT-FITC-3′, 5′-LC Red640-CAG CGC GTC ATG CAC CTT T-3′.

Results

Th1 differentiation of P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells can be induced in an IFN-γ- and IL-12-independent manner

P25 TCR-Tg mice, that expressed TCR-α5 and -β11 chains on CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood, the spleen, lymph node and thymocytes, were generated. FACS analysis revealed that over 98% of splenic CD4+ T cells from RAG-2–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice expressed TCR Vβ11-chain. T-bet and IFN-γ mRNA expression was not detected, by RT-PCR, in splenic CD4+ cells of RAG-2–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice (data not shown), suggesting that CD4+ T cells in P25 TCR-Tg mice are not preactivated.

RAG-2–/– P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ splenic T cells were stimulated in vitro for 6 days with Peptide-25 in the presence of APC. After 6 days in culture, the proliferated cells were harvested and re-stimulated for another day with plate-coated anti-CD3. After culturing, IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were analysed by cytoplasmic staining. Naive CD4+ T cells stimulated with Peptide-25 in the presence of APC became solely IFN-γ-producing cells under non-skewing conditions (Fig. 1a, left hand panel). When RAG-2–/– P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with Peptide-25 in the presence of APC, IL-4, anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-12 (Th2-skewing conditions), a significant proportion of the T cells became IL-4-producing cells (Fig. 1a, right hand panel), while IFN-γ-producing T cells were undetectable. These results indicate that Peptide-25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells are not precommitted to differentiation towards Th1 before P25 stimulation and retain the potential to differentiate into both Th1 and Th2 lineages.

In addition to the TCR signals IFN-γ and IL-12 play an important role in Th1 development and differentiation. Naive CD4+ T cells from RAG-2–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were stimulated with Peptide-25 and APC in the presence of anti-IFN-γ, anti-IL-12 or a combination of them for 6 days. FACS analysis revealed that in cultures of CD4+ T cells from RAG-2–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice (Fig. 1a), substantial numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells were observed even when stimulated in the presence of anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-12.

To confirm bioactivities of anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-12, we stimulated naive CD4+ T cells from WT mice with anti-CD3 in the presence of splenic APC together with or without anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-12. Addition of anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-12 completely blocked anti-CD3-induced-Th1 differentiation (Fig. 1b). We also confirmed, in separate experiments by using bioassay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, that each of the anti-cytokine antibodies could completely neutralize relevant cytokine activity specifically.

Stimulation of P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells with IL-12/IL-18–/– splenic APC and Peptide-25 induced differentiation into IFN-γ-producing cells. This was quantitatively similar to the differentiation seen under conditions of Peptide-25 stimulation in the presence of WT APC (Fig. 1c). These results imply that IFN-γ and IL-12 are not essential for development of Th1 cells from naive CD4+ T cells in response to Peptide-25.

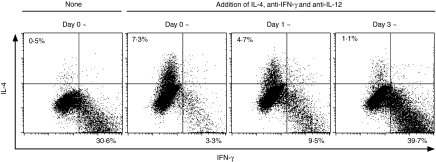

Commitment of P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells to Th1 differentiation is determined within 3 days after Peptide-25 and splenic APC stimulation

It has been shown that IFN-γ and IL-12 play important roles in sustained development and differentiation of Th1 cells. To examine the roles of IFN-γ and IL-12 in the stabilization of Th1 differentiation, we established four groups of P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells, cultured for 6 days in the presence of Peptide-25 and APC. During the culture periods, three groups of culture received a mixture of IL-4, anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-12 on day 0, 1, or 3, for converting non-skewing to Th2-skewing conditions. After culturing with Peptide-25 and APC, the proportions of IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were quantified. Adding IL-4, anti-IFN-γ, and anti-IL-12 on day 0 or 1 caused the proportion of cells producing IL-4 to be significantly increased, whereas the proportion of cells producing IFN-γ decreased (Fig. 2). Addition of IL-4, anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-12 to the culture on day 3 or thereafter was ineffective and predominant proportions of IFN-γ-producing cell were observed. These results suggest that IFN-γ and IL-12 are indispensable for the full commitment of naive CD4+ T cells to Th1 differentiation, and for the stabilization of Th1-developing cells within 3 days after onset of culture.

Figure 2.

Commitment to Th1 differentiation of P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells occurs within 3 days after stimulation with Peptide-25. P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells were separated into four groups. Each group was stimulated with 10 µg/ml of Peptide-25 in the presence of splenic APC. IL-4, anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-12 were added into each of three groups of culture on days 0, 1, and 3. After the culture the primed cells were re-stimulated and IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were assessed. Events shown are gated on live Vβ11+ cells. Representative results of three separate experiments were displayed.

Peptide-25-stimulated CD4+ T cells of P25 TCR-Tg mice are able to differentiate to Th1 cells independently of costimulatory molecules

The current dogma of Th cell differentiation is that costimulation of naive CD4+ T cells via membrane-bound molecules on the APC plays an important role in determining Th differentiation into Th1 or Th2 subset. To examine the role of costimulatory molecules in Th1 development, P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated for 6 days in vitro with various concentrations of Peptide-25 or APL in the presence of I-Ab-CHO, because I-Ab-CHO does not express detectable levels of CD54, CD80, CD86, CD252 and CD275. APL has weaker avidity to P25 TCR than Peptide-25 (less than 1/30).36 As a control, splenic APC was also used. The majority of cytokine-producing T cells were IFN-γ-producing cells, when 10 µg/ml (6·0 µm) of Peptide-25 in the presence of I-Ab-CHO was used as the stimulant (Fig. 3a, upper panel). The T cells stimulated with 0·1 µg/ml (0·06 µm) of Peptide-25 or 10 µg/ml (6·0 µm) of APL in the presence of I-Ab-CHO differentiated into IL-4-producing cells. Essentially similar results were obtained when P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with Peptide-25 or APL in the presence of splenic APC in place of I-Ab-CHO (Fig. 3a, lower panel). Considerable proportions of IFN-γ-producing cells were detected even when anti-IFN-γ was added during the culture of naive CD4+ T cells with Peptide-25 in the presence of I-Ab-CHO (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, naive CD4+ T cells from STAT1–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice could differentiate into solely IFN-γ-producing cells when they were cultured with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO (Fig. 3c).

There remains a possibility that our observation might be simply explained with the difference in proliferative rate between Th1 and Th2 cells. The cell recovery after culturing P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells stimulated with low dose Peptide-25 (0·1 µg/ml) that induced Th2 differentiation was approximately 65% of that stimulated with high dose Peptide-25 (10 µg/ml) that induced Th1 differentiation. On the other hand, the cell recovery after stimulation of P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells with APL (10 µg/ml) that induced Th2 differentiation was similar to that stimulation with high dose Peptide-25 (10 µg/ml). Furthermore, we examined the division cycle number of P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells on days 1–4 after the stimulation with 10 µg/ml or 0·1 µg/ml of Peptide-25 or 10 µg/ml of APL using the fluorescent dye CFSE. In all stimulation, the cells started to divide by 48 hr and stopped dividing by 96 hr after the stimulation (Fig. 3d). High-dose Peptide-25 and APL stimulation induced six to eight cell divisions. On the other hand, low-dose Peptide-25 induced five to seven cell divisions. These results suggest that the phenomenon described above might not be simply explained by the difference in proliferative rate between Th1 and Th2 cells.

Taken together, these results indicate that P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells do differentiate into Th1 cells in the absence of costimulatory molecules.

TCR stimulation induces T-bet up-regulation and GATA-3 down-regulation in an IFN-γ-independent manner

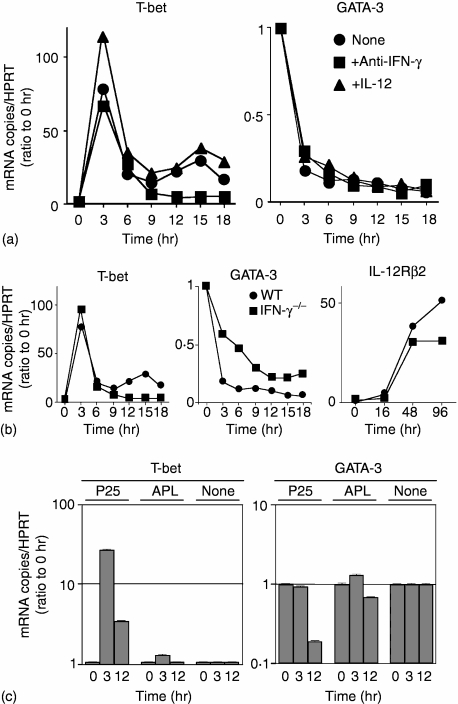

The expression of Th1 specific transcription factors is thought to induce chromatin remodelling of Th1-specific cytokine genes. P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated in vitro with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO for various periods of time. The expression of T-bet, GATA-3 and IL-12Rβ2 was analysed periodically by quantitative real-time PCR. Three hr after stimulation (early phase), T-bet expression was elevated up to 70–110-fold over unstimulated cells, by 9 hr after stimulation the expression level of T-bet sharply dropped. Moreover, anti-IFN-γ presence did not affect T-bet expression. The second-phase (late-phase) of T-bet expression began after 12 hr of stimulation and peaked (50-fold higher expression over control levels) at 15 hr after the stimulation (Fig. 4a). Addition of IL-12 in the culture slightly enhanced T-bet expression, in both early and late-phases. The late-phase T-bet expression was decreased to almost the same levels as naive CD4+ T cells when anti-IFN-γ was added. In contrast, GATA-3 expression was rapidly decreased after the Peptide-25 stimulation in all conditions tested. Similar analysis was carried out using naive CD4+ T cells from IFN-γ–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice. Results revealed that early phase T-bet expression in IFN-γ–/– P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells was enhanced to an extent similar to that seen in WT P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells, although no late-phase T-bet expression was seen in IFN-γ–/– P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells. GATA-3 expression was down-regulated in IFN-γ–/– P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells upon stimulation similarly to that seen in WT P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells, although a slightly slower and milder down-regulation was seen. The IL-12Rβ2 expression gradually increased for 48 hr after stimulation regardless of IFN-γ (Fig. 4b). Up-regulation of T-bet expression was also observed when naive CD4+ T cells from STAT1–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were stimulated in vitro with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO in the presence of anti-IFN-γ (data not shown). These results indicate that IFN-γ/STAT1 is dispensable to induce the T-bet expression although IFN-γ/STAT1 is indispensable to maintain the expression.

Figure 4.

Kinetics of induction of T-bet, GATA-3 and IL-12Rβ2 transcripts in Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO-activated T cells. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated for indicated periods of time (hr) with Peptide-25- or APL-loaded I-Ab-CHO. Cells were collected at the indicated time points and RNA was extracted. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed for assessing the mRNA expression of T-bet, GATA-3 or IL-12Rβ2. Each sample was normalized to HPRT. Data shown are ratios of test mRNA copies to mRNA copies of unstimulated cells. The values represent the mean and SD. When error bars are not visible they are smaller than the symbol width. Results are presented for one of three experiments performed, with similar results in each experiment. (a) P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO alone or in the presence of anti-IFN-γ (3 µg/ml) or rIL-12 (10 ng/ml). (b) Naive CD4+ T cells either from WT P25 TCR-Tg mice or IFN-γ–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were stimulated with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO. (c) P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO or APL-loaded I-Ab-CHO. As a control, cells were incubated without any stimulus.

We also analysed expression of T-bet and GATA-3 in P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells in response to APL-loaded I-Ab-CHO. Surprisingly, neither enhancement of T-bet expression nor down-regulation of GATA-3 was observed (Fig. 4c).

Taken together, these results suggest that the interaction between Peptide-25/I-Ab and TCR directly regulates the expression of T-bet, GATA-3, and IL-12Rβ2, thereby determining the fate of naive CD4+ T cells for differentiation into Th1 subset.

Th1 differentiation can be induced in T-bet-dependent and T-bet-independent manners

We next examined the role of T-bet transcription factor in Th1 differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells from P25 TCR-Tg mice by priming with Peptide-25. Expression of T-cell activation markers on naive CD4+ T cells from T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice was comparable to these of WT P25 TCR-Tg mice (Fig. 5a). To confirm the functional deficiency of T-bet in T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice, we examined the IFN-γ production in primary response of naive CD4+ T cells from T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice to anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 according to procedures previously described by Szabo et al.34 Consistent with Szabo's report34, T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells did not produce IFN-γ, although WT P25 TCR-Tg T cells produced large amounts of IFN-γ (data not shown). These results indicate that T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells is functionally T-bet deficient.

We compared the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells from T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice and naive CD4+ T cells from WT P25 TCR-Tg mice in response to Peptide-25. Naive CD4+ T cells from T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice or WT P25 TCR-Tg mice were stimulated in vitro for 6 days with Peptide-25 in the presence of splenic APC. After 6 days in culture, the proliferated cells were harvested and re-stimulated for another day with plate-coated anti-CD3. After culturing, IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells were analysed by cytoplasmic staining. Intriguingly, naive CD4+ T cells from T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice differentiated into Th1 cells upon Peptide-25 stimulation (Fig. 5b). Naive CD4+ T cells from WT P25 TCR-Tg mice, when identically stimulated, showed far higher induction of IFN-γ production. When compared between WT and T-bet null background, the lack of T-bet protein clearly reduced proportions of IFN-γ-producing Th cells from 46·5% to 14·6%, indicating that about two-third of Th1 differentiation is contributed to T-bet and one-third of the response is T-bet independent. A significant proportion became IL-4-producing T cells when naive CD4+ T cells from T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were stimulated with Peptide-25. APL stimulation predominantly induced IL-4-producing T cells (Fig. 5b). As for proliferative response, Peptide-25 and APL induced six to eight cell divisions of the T cells similarly (Fig. 5c).

To examine whether IFN-γ and IL-12 affect Th1 differentiation in T-bet–/– T cells, we added neutralization antibodies of IFN-γ and IL-12 to the culture of CD4+ T cells from T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice. Results revealed that addition of anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-12 did not alter proportions of IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells significantly (Fig. 5d). We infer from these results that there may be T-bet-dependent and T-bet-independent pathways for Th1 commitment and its differentiation.

Upon Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO-stimulation, GATA-3 expression in CD4+ T cells of WT P25 TCR-Tg mice and T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice was then compared. Results revealed that Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO dependent GATA-3 expression in T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells was comparable to that seen in WT P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5e).

Discussion

The differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells to either Th1 or Th2 cells is a critical aspect of any immune response, with broad implications in host defence against disease pathogenesis. Many factors influence polarization of CD4+ T cells to Th1 or Th2, including those collectively termed ‘strength of stimulation’, such as peptide dose and duration of TCR engagement. T-cell activation requires signals emanating from the TCR complex along with those generated through costimulatory molecules, various cytokines and transcription factors, these are all key determinants of the differentiation into Th1 or Th2 cells, however, exactly what is the key primal signal is unclear.

The strength of interaction mediated through the TCR and MHC/peptide complex directly affect lineage commitment of Th cells.16,38,39 Stimulation with high affinity peptides and high antigen dose favours Th1 differentiation and stimulation with low affinity peptides and low antigen dose favours Th2 differentiation.14–16 The use of APL has provided convincing evidence that the strength of the signal transmitted via the TCR influences lineage commitment.14,16 Stimulation of P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells with high dose Peptide-25 (10 µg/ml (6·0 µm)) preferentially induces Th1 development. In contrast, when T cells were stimulated with low dose Peptide-25 (0·1 µg/ml (0·06 µm)), a dominant Th2 response was observed (Fig. 3). Our observations are consistent with the published data.15,38

It is well known that costimulation is indispensable in Th1 and Th2 differentiation.40 Our results showed that Th1 and Th2 differentiations could be induced when P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with Peptide-25-loaded and APL-loaded I-Ab-CHO, respectively (Fig. 3). As Chinese hamster ovary cells do not express detectable levels of CD54, CD80, CD86, CD252 and CD275, we are in favour of the hypothesis that preferential induction of Th1 and Th2 development upon Peptide-25 and APL stimulation, respectively, may be independent of these well-known costimulating signals from APC.

In this report, we used plate-coated anti-CD3 stimulation in second culture to evaluate the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells. It has been reported that plate-coated anti-CD3 induced the activation-induced cell death (AICD) in activated CD4+ T cells41 and Th1 cells appears to be more susceptible to AICD than Th2 cells.42 Therefore, we compared the ability of AICD induction between plate-coated anti-CD3 and another mitogenic stimulation such as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)/ionomycin. Purified naive CD4+ T cells from WT C57BL/6 mice were stimulated with soluble anti-CD3 in the presence of splenic APC under either Th1- or Th2-skewing conditions for 6 days. After the culture the viable cells were restimulated with plate-coated anti-CD3 for 24 hr or 10 ng/ml of PMA and 1 µm of ionomycin for 4 hr. The AICD was assayed by FACS using 7AAD. We did not observe a significant difference in the ability of AICD induction between plate-coated anti-CD3 and PMA/ionomycin stimulations. The cells positively stained with 7AAD were 26·3% and 18·2% in Th1 cells restimulated with plate-coated anti-CD3 and PMA/ionomycin, respectively, and 25·1% and 19·8% in Th2 cells restimulated with anti-CD3 and PMA/ionomycin, respectively.

A complex network of gene transcription events is likely to be involved in establishing an environment that promotes Th1 development. It has been reported that naive CD4+ T cells express little T-bet or IL-12Rβ2 and are unresponsive to IL-12, and T-bet appears to initiate Th1 lineage development from naive CD4+ T cells both by activating Th1 genetic programmes and by repressing the opposing Th2 programmes.24 It has been hypothesized that upon activation, TCR-derived signals alone may induce T-bet, but this alone is not sufficient to permit its optimal expression26. Interestingly, T-bet expression is markedly elevated, peaking 3 h after Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab CHO stimulation of IFN-γ–/– P25 TCR-Tg T cells (Fig. 4b) and STAT1–/– P25 TCR-Tg T cells as well (data not shown). Furthermore, naive CD4+ T cells from STAT1–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice were capable of differentiating into IFN-γ-producing cells upon stimulation with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO (Fig. 3b). IL-12Rβ2 expression detected at 24 hr after stimulation is also observed in IFN-γ–/– P25 TCR-Tg T cells. These results indicate that those T-bet and IL-12Rβ2 expressions are IFN-γ/STAT1 and costimulatory signal independent. The sustained T-bet and IL-12Rβ2 expression observed 15 h and 48 hr, respectively, after the peptide stimulation are IFN-γ/STAT1 dependent (Fig. 4b). Exposure of T cells after TCR activation to IFN-γ may be important for the sustained T-bet induction and may be relate to full Th1 differentiation. So the interaction between Peptide-25/I-Ab and P25 TCR may directly induce T-bet and IL-12Rβ2 that may lead to Th1 differentiation. Significant proportions of Peptide-25-stimulated T cells from T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice become IFN-γ-producing cells (Fig. 5), although large proportions of the T cells become IL-4-producing cells. Proportions of IFN-γ-producing cells in Peptide-25-stimulated T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg T cells are not altered even in the presence of anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-12 antibodies. Therefore, IFN-γ and IL-12 are dispensable for T-bet-independent Th1 differentiation.

GATA-3 is a Th2-specific transcription factor, which is thought to be induced by STAT6 and regulate chromatin remodelling of the Th2 cytokine locus. It has been reported that retroviral ectopic expression of T-bet does not suppress either GATA-3 or Th2 cytokine expression in committed Th2 cells.27 GATA-3 expression was rapidly decreased soon after the P25 TCR stimulation by Peptide-25, under the conditions tested. Activated CD4+ T cells from P25 TCR-Tg mice produced IFN-γ, but not IL-4, within 24 hr of stimulation with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO, determined by enzyme-linked immunospot assay (data not shown). These results suggest that the acute down-regulation of GATA-3 expression after stimulation with Peptide-25-loaded I-Ab-CHO may be induced primarily as a result of TCR signals, but this may not be caused by direct inhibition through T-bet.

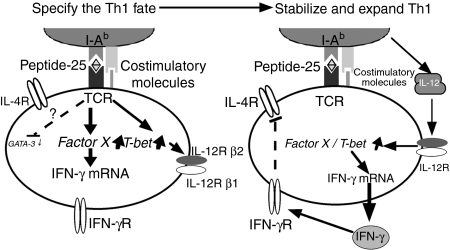

The results of this study have been integrated to suggest a mechanism of Th1 differentiation (Fig. 6). Immediately after TCR stimulation by Peptide-25/I-Ab, P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells express T-bet mRNA independently of IFN-γ signalling while GATA-3 expression is suppressed. This acute induction of T-bet may induce chromatin remodelling of the ifn-γ locus. As a result, the activated CD4+ T cells transcribe IFN-γ, but not IL-4, this enhances T-bet expression further through STAT1 activation, leading to IL-12Rβ2 up-regulation and the termination of IL-4 signal transduction. IL-12 produced by activated APC maintains T-bet and IFN-γ expression through STAT4 activation. Transcription factors other than T-bet may orchestrate, with T-bet, the commitment of naive Th cells towards Th1 development.

Figure 6.

The pathway of Th1 development illustrates how external TCR signals play a role differently from IFN-γ and IL-12, and how these pathways are intrinsically ordered. (Left-hand panel) Antigen receptor ligation enables T-bet to specify the Th1 fate, including T-bet auto-induction, IL-12Rβ2 induction, and primary remodelling of the ifn-γ locus. (Right-hand panel) The actions of T-bet then enable IFN-γ and probably IL-12 to signal for survival and growth of Th1 cells, and interact for secondary enhancement of IFN-γ gene expression.

In summary, we have presented that P25 TCR-Tg naive CD4+ T cells stimulated with Peptide-25/I-Ab polarize to Th1 differentiation preferentially in the absence of IFN-γ and IL-12. Furthermore, Th1 development of naive CD4+ T cells from T-bet–/– P25 TCR-Tg mice is inducible. We propose that direct interaction of the specific antigenic peptide MHC class II complex and TCR may primarily influence the determination of naive CD4+ T cell fate in development towards the Th1 subset. The regulatory effect seems to occur independently of costimulation and Th1 inducible cytokine, IFN-γ and IL-12, and controls the fate of naive CD4+ T cells for differentiation into Th1 subsets.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr S. Takaki and all lab members for their valuable suggestions and encouragement throughout this study. We thank Drs Y. Iwakura, L. H. Glimcher, K. Nakanishi, R. D. Schreiber and Y. Fukui for providing mice and cells. We are indebted to Richard Jennings for his critical review of this manuscript.

This work was supported by Special Coordination Funds on ‘Molecular Analysis of the Immune System and Its Manipulation on Development, Activation and Regulation’ for Promoting Science and Technology (K.T.); by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas and on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture; Grant-in-Aid for Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan; and by Uehara Foundation.

Abbreviations:

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- IL

interleukin

- Th

T helper

- IFN

interferon

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- R

receptor

- P25 TCR-Tg mice

TCR transgenic mice that recognize Peptide-25

- APL

altered peptide ligand

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- PE

phycoerythrin

- L

ligand

- WT

wild type

- I-Ab-CHO

Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing I-Ab

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- CFSE

5-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

References

- 1.Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136:2348–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbas AK, Murphy KM, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–93. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Garra A. Cytokines induce the development of functionally heterogeneous T helper cell subsets. Immunity. 1998;8:275–83. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy KM, Ouyang W, Farrar JD, Yang J, Ranganath S, Asnagli H, Afkarian M, Murphy TL. Signaling and transcription in T helper development. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:451–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Shea JJ, Paul WE. Regulation of TH1 differentiation – controlling the controllers. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:506–8. doi: 10.1038/ni0602-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy KM, Reiner SL. The lineage decisions of helper T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:933–44. doi: 10.1038/nri954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Peng SL, Glimcher LH. Molecular mechanisms regulating Th1 immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:713–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.140942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thierfelder WE, van Deursen JM, Yamamoto K, et al. Requirement for Stat4 in interleukin-12-mediated responses of natural killer and T cells. Nature. 1996;382:171–4. doi: 10.1038/382171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan MH, Sun YL, Hoey T, Grusby MJ. Impaired IL-12 responses and enhanced development of Th2 cells in Stat4-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;382:174–7. doi: 10.1038/382174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda K, Tanaka T, Shi W, et al. Essential role of Stat6 in IL-4 signalling. Nature. 1996;380:627–30. doi: 10.1038/380627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimoda K, van Deursen J, Sangster MY, et al. Lack of IL-4-induced Th2 response and IgE class switching in mice with disrupted Stat6 gene. Nature. 1996;380:630–3. doi: 10.1038/380630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan MH, Schindler U, Smiley ST, Grusby MJ. Stat6 is required for mediating responses to IL-4 and for development of Th2 cells. Immunity. 1996;4:313–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal S, Rao A. Modulation of chromatin structure regulates cytokine gene expression during T cell differentiation. Immunity. 1998;9:765–75. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfeiffer C, Stein J, Southwood S, Ketelaar H, Sette A, Bottomly K. Altered peptide ligands can control CD4 T lymphocyte differentiation in vivo. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1569–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosken NA, Shibuya K, Heath AW, Murphy KM, O'Garra A. The effect of antigen dose on CD4+ T helper cell phenotype development in a T cell receptor-alpha beta-transgenic model. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1579–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tao X, Grant C, Constant S, Bottomly K. Induction of IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells by antigenic peptides altered for TCR binding. J Immunol. 1997;158:4237–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rulifson IC, Sperling AI, Fields PE, Fitch FW, Bluestone JA. CD28 costimulation promotes the production of Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 1997;158:658–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato T, Nariuchi H. Polarization of naive CD4+ T cells toward the Th1 subset by CTLA-4 costimulation. J Immunol. 2000;164:3554–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohshima Y, Yang LP, Uchiyama T, Tanaka Y, Baum P, Sergerie M, Hermann P, Delespesse G. OX40 costimulation enhances interleukin-4 (IL-4) expression at priming and promotes the differentiation of naive human CD4+ T cells into high IL-4-producing effectors. Blood. 1998;92:3338–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akiba H, Miyahira Y, Atsuta M, et al. Critical contribution of OX40 ligand to T helper cell type 2 differentiation in experimental leishmaniasis. J Exp Med. 2000;191:375–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong C, Juedes AE, Temann UA, Shresta S, Allison JP, Ruddle NH, Flavell RA. ICOS co-stimulatory receptor is essential for T-cell activation and function. Nature. 2001;409:97–101. doi: 10.1038/35051100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salomon B, Bluestone JA. LFA-1 interaction with ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 regulates Th2 cytokine production. J Immunol. 1998;161:5138–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smits HH, de Jong EC, Schuitemaker JH, Geijtenbeek TB, van Kooyk Y, Kapsenberg ML, Wierenga EA. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1/LFA-1 ligation favors human Th1 development. J Immunol. 2002;168:1710–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, Zhang X, Fathman CG, Glimcher LH. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang WX, Yang SY. Cloning and characterization of a new member of the T-box gene family. Genomics. 2000;70:41–8. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lighvani AA, Frucht DM, Jankovic D, et al. T-bet is rapidly induced by interferon-γ in lymphoid and myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:15137–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261570598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Afkarian M, Sedy JR, Yang J, Jacobson NG, Cereb N, Yang SY, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. T-bet is a STAT1-induced regulator of IL-12R expression in naive CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:549–57. doi: 10.1038/ni794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullen AC, High FA, Hutchins AS, et al. Role of T-bet in commitment of TH1 cells before IL-12-dependent selection. Science. 2001;292:1907–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1059835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yanagisawa S, Koike M, Kariyone A, Nagai S, Takatsu K. Mapping of Vβ11+ helper T cell epitopes on mycobacterial antigen in mouse primed with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int Immunol. 1997;9:227–37. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kariyone A, Higuchi K, Yamamoto S, et al. Identification of amino acid residues of the T-cell epitope of Mycobacterium tuberculosisα antigen critical for Vβ11+ Th1 cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4312–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4312-4319.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takatsu K, Kariyone A. The immunogenic peptide for Th1 development. Int Immunopharmacol. 2003;3:783–800. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5769(02)00209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kariyone A, Tamura T, Kano H, Iwakura Y, Takeda K, Akira S, Takatsu K. Immunogenicity of Peptide-25 of Ag85B in Th1 development: role of IFN-γ. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1183–94. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kikuchi T, Uehara S, Ariga H, Tokunaga T, Kariyone A, Tamura T, Takatsu K. Augmented induction of CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell response and antitumour resistance by T helper type 1-inducing peptide. Immunology. 2006;117:47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Stemmann C, Satoskar AR, Sleckman BP, Glimcher LH. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-γ production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science. 2002;295:338–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1065543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seki E, Tsutsui H, Tsuji NM, et al. Critical roles of myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent proinflammatory cytokine release in early phase clearance of Listeria monocytogenes in mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:3863–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamura T, Ariga H, Kinashi T, et al. The role of antigenic peptide in CD4+ T helper phenotype development in a T cell receptor transgenic model. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1691–9. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyons AB, Parish CR. Determination of lymphocyte division by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1994;171:131–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Constant S, Pfeiffer C, Woodard A, Pasqualini T, Bottomly K. Extent of T cell receptor ligation can determine the functional differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1591–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Constant SL, Bottomly K. Induction of Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cell responses: the alternative approaches. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oosterwegel MA, Mandelbrot DA, Boyd SD, Lorsbach RB, Jarrett DY, Abbas AK, Sharpe AH. The role of CTLA-4 in regulating Th2 differentiation. J Immunol. 1999;163:2634–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Radvanyi LG, Mills GB, Miller RG. Religation of the T cell receptor after primary activation of mature T cells inhibits proliferation and induces apoptotic cell death. J Immunol. 1993;150:5704–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang X, Brunner T, Carter L, et al. Unequal death in T helper cell (Th) 1 and Th2 effectors: Th1, but not Th2, effectors undergo rapid Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1837–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]