Abstract

The neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) protects immunoglobulin G (IgG) from catabolism and is also responsible for IgG absorption in the neonatal small intestine. However, whether it mediates the transfer of IgG from plasma to milk still remains speculative. In the present study, we have generated transgenic mice that over-express the bovine FcRn (bFcRn) in their lactating mammary glands. Significantly increased IgG levels were observed in the sera and milk from transgenic animals, suggesting that the over-expressed bFcRn could bind and protect endogenous mouse IgG and thus extend its lifespan. We also found that injected human IgG showed a significantly longer half-life (7–8 days) in the transgenic mice than in controls (2·9 days). Altogether, the data suggested that bFcRn could bind both mouse and human IgG, showing a cross-species FcRn–IgG binding activity. However, we found no selective accumulation of endogenous mouse IgG or injected bovine IgG in the milk of the transgenic females, supporting a previous hypothesis that IgG was transported from serum to milk in an inverse correlation to its binding affinity to FcRn.

Keywords: immunoglobulin G, neonatal Fc receptor, transgenic mice

Introduction

Transfer of maternal antibodies [mainly immunoglobulin G (IgG)] from mother to fetuses or newborns is essential for the development of their immune system and the protection of young animals from various pathogens in their early lives.1–5 Depending on species, animals use different approaches to transfer maternal antibodies. Maternal IgG is transferred mainly through the placenta before birth in guinea pigs, rabbits and humans,6,7 whereas in ungulates such as sheep, cows and pigs, newborns receive maternal antibodies exclusively through colostrum.5 In rodents, maternal antibodies are transported to their offspring both antenatally and neonatally.4,8,9

A pivotal molecule responsible for the transfer of maternal IgG is neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn), which was first identified in the small intestine of neonatal rats where it mediates uptake of IgG from milk.10 FcRn is a major histocompatibility complex class I related molecule consisting of an α-chain and β2-microglobulin and its major roles are to protect both IgG and albumin from catabolism and so extend their half-lives3,11,12 in addition to transporting IgG through multiple mucosal barriers.

In the small intestine of newborn rodents, suckled milk IgGs are absorbed into the circulation by FcRn.10,13 However, whether FcRn is involved in the accumulation of IgG in colostrum remains controversial. Evidence derived in ruminants is in favour of the hypothesis that FcRn selectively transports IgG from serum to milk.14–17 Previous studies have shown that expression of the Fc receptor in the mammary gland correlates with the period of highest IgG-transfer into milk in three species: possum, sheep and pigs.15,18,19 However, the data obtained from rodent models supports the notion either that FcRn was not involved in IgG transfer from serum to milk or that transport of IgG was in an inverse correlation with their binding affinity to FcRn.9,13 In 1995, Israel et al. measured the milk IgG level in mid-lactation of β2-microglobulin gene (β2m) knockout mice. They revealed no obvious difference between β2m-deficient and heterozygous mice,13 suggesting that FcRn may not transport IgG back from blood to the mammary gland. Another study also showed that FcRn could be identified in the epithelial cells of the acini in the mammary glands of lactating mice, and that the FcRn may function as a recycling receptor rather than a transport receptor.9

The postulated function of FcRn in ruminants to transport IgG from serum to milk so far relies only on indirect evidence obtained by studies on FcRn messenger RNA (mRNA) expression and protein distribution in the mammary gland around parturition.15,16,18,20 To address this question, we have generated a transgenic mouse model in which bovine FcRn (bFcRn) is over-expressed in the lactating mammary gland. Our particular objective was to test the hypothesis that the bFcRn selectively transports IgG from serum to milk. As only colostrum contains a high concentration of IgG in large domestic animals, it would be of interest, for therapeutic purposes, to be able to maintain selective IgG transfer during the whole lactation period. Animal milk has become a safe, attractive source for purification of biologically or pharmaceutically important proteins. Recently, transchromosomic calves producing human immunoglobulins were generated.21 One of the major technical concerns is how to selectively transport the expressed human polyclonal IgG from serum to milk, which would dramatically decrease the production cost and enhance the biological safety of the immunoglobulin preparations.

Materials and methods

Construction of the bFcRn expression vectors

Bovine FcRn α-chain14 and bovine bovine β2-microglobulin (bβ2m) cDNAs, respectively, were cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI), (a plasmid containing the cDNA of the bβ2m was a kind gift from Dr Shirley A. Ellis, Institute for Animal Health, Compton, UK). Both the cDNA fragments were re-amplified with addition of the Xho I site to their ends and again cloned into a T vector. The bFcRn α-chain and bβ2m cDNA fragments were subsequently inserted into the pBC1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using the Xho I site, generating two expression vectors, pBC1-bFcRn and pBC1-bβ2m.

Production of the bFcRn transgenic mice

Kunming White mice were purchased from Beijing Laboratory Animal Research Centre (Beijing, China). To perform microinjection, both the heavy chain (pBC1-bFcRn) and light chain (pBC1-bβ2m) constructs were digested with NotI and SalI for linearization to remove the prokaryotic sequence. The fragments containing the 16·9 kilobase (kb) heavy chain and the 16·1-kb light chain were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and electro-elution. These two DNA fragments were mixed at an equal concentration (3 ng/μl) and microinjected into fertilized Kunming White mouse eggs that were subsequently re-implanted into pseudo-pregnant females. The mice were housed in the specific pathogen-free transgenic mouse centre at the China Agricultural University, Beijing.

Polymerase chain reaction and Southern blot analysis of the transgenic mice

Genomic DNA was isolated from tail tissues of mice. A pair of pBC1 vector-specific primers was used to screen for transgenic mice (upstream primer: 5′-GATTGACAAGTAATACGCTGTTTCCTC-3′ and downstream primer: 5′-CATCAGAAGTTAAACAGCACAGTTAG-3′). The primers were able to amplify both the α-chain (2·3 kb) and β2m (1·2 kb). The PCR parameters were: 30 cycles of 94° for 1 min, 58° for 1 min, and 72° for 2 min 30 seconds. After polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screening, the identities of transgenic mice were further confirmed by Southern blot. Integration of the constructs was identified by Nco I digestion of genomic DNA (10 μg) extracted from the tail.22 DNA fragments were separated on a 0·8% agarose gel and blotted on HybondTM-N+ membrane (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). Transgene integration, integrity and copy number were determined using a 6-kb NcoI-digested fragment including part of the promoter and the α-chain and another 5-kb Nco I-digested fragment was used for detection of the β2m. Probes were labelled with α-32P-dCTP using a random primer DNA labelling kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Copy numbers of transgenes were estimated by comparing the hybridization signal density of the genomic DNA samples and plasmid DNA.

Northern blot analysis of transgene expression

Total RNA was extracted from the mammary gland and additional tissues (heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) using TRIzol (Tiangen Technologics, Beijing, China). Transgene expression was measured at 8 or 12 days of lactation. Northern blot analysis was performed according to a standard protocol using the bFcRn cDNA as a probe.23 Briefly, the RNA preparations were separated by electrophoresis under a denaturing condition on a 0·7% agarose 3-[N-MorphoLino] propane-sulfonic acid (MOPS)/formaldehyde gel and subsequently transferred to HybondTM-N+ membrane (Amersham) using downward alkaline capillary blotting. Endogenous expression of the mouse FcRn (mFcRn) gene and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were measured using the mFcRn (1·2 kb) and GAPDH (1 kb) cDNA as probes.18

Quantitative real-time PCR (SYBR green assay)

First-strand cDNA was synthesized using 2 μg RNA (at 8 or 12 days lactation) with oligo-dT (16) primer (Promega). Mouse and bovine FcRn messenger expression levels were monitored on the ABI PRISM 7900 Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The PCR primers were designed in such a way that they spanned an intron in the genomic DNA, with about five or six bases of the 3′ end of one primer being complementary to the adjacent exon24 (Table 1). The presence of intron sequences prevents the primer from priming on a genomic DNA template. Primers for the internal control (mouse GAPDH) were obtained from Applied Biosystems.

Table 1.

Primers used in real-time PCR amplifications

| Target | Forward primer (5′→3′) | Reverse primer (5′→3′) | Product length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | CGTGCCGCCTGGAGAAACCTG | AGAGTGGGAGTTGCTGTTGAAGTCG | 140 |

| mFcRn | CAGCCTCTCACTGTGGACCTAGA | TCGCCGCTGAGAGAAAGC | 164 |

| bFcRn | CGATGTCCTCCCTCTGGATTT | TTTCCAGTCGCAGTCAATTCAA | 131 |

Data analysis

For each sample, expression of the GAPDH gene was used to normalize the amount of the investigated transcript. Relative mouse FcRn and bovine FcRn mRNA expression levels were calculated using the threshold cycle (ΔΔCt) method25 in relation to mouse FcRn expression in wild-type mice. In the ΔΔCt method, ΔCt values represent values from wild-type (WT) mice (calibrator or one-fold sample) in relation to the ΔCt value representing mRNA from mammary cells over-expressing bovine FcRn (WT/bFcRn) such that: ΔCt (WT/bFcRn) − ΔCt (WT) = ΔΔCt (WT/bFcRn). The relative mRNA values were calculated as 2– ΔΔCt based on the results of control experiments with an efficiency of the PCR of approximately 96–98%.25

IgG transfer and clearance

Transgenic female mice were mated with non-transgenic male mice. At mid-lactation, the mice were injected intravenously with 500 μg bovine IgG1 and IgG2 mixture (containing equal amounts of IgG1 and IgG2, Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX). Three mice from each transgenic line were used. Milk and serum samples were collected after injection. Clearance of human IgG in lactating mice was determined as described elsewhere.26 Briefly, 1 mg human IgG (Bayer HealthCare, Berkeley, CA) was injected intravenously into mice and sera, prepared from retro-orbital plexus blood, were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Determination of IgG concentration in milk and serum

Milk and sera were collected during mid-lactation. ELISA was performed using quantification kits for murine and bovine IgG (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The standard IgG solution (0·2 mg IgG/ml) (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.) was used to create the standard curve. The analysis of variance (anova) test was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Construction of the bFcRn expression vectors and generation of transgenic mice

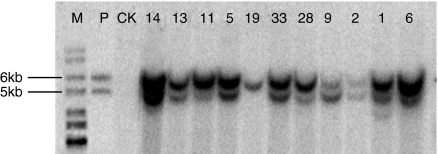

We made two expression constructs containing the bFcRn α-chain and bβ2m subunit cDNA sequences using the pBC1 vector, respectively. Transgenic mice were generated by co-microinjection of Not I and Sal I linearized DNA fragments from the two constructs. Both PCR and Southern blot analysis were conducted to identify transgenic mice. To test the integrity of the integrated transgenes, we digested the genomic DNA using the Nco I that would generate a DNA fragment containing both promoter and cDNA insert. Ten transgenic F0 mice, possessing both the α-chain and β2m, and one having only the α-chain were identified (Fig. 1). The integrated genes in all lines were shown to be intact and copy numbers of the transgenes varied from 1 to 15 copies per cell. Six female transgenic mice were generated and lines 2, 6, 9, 11, 14 and 19 were established. Five of these lines contained both the α-chain and bβ2m with copy numbers varying from 1 to 15. Line 19 contained only the α-chain.

Figure 1.

Southern blot analysis of the genomic DNA digested by Nco I from 11 transgenic founders. M, 1-kb DNA ladder; P, plasmid DNA as a positive control; CK, 10 μg genomic DNA of non-transgenic mice used as a negative control. Transgenic lines are indicated at the top of lanes. Signal quantification was performed by scanning band density using Alphaimager 2200 (Alpha Imaging System, US).

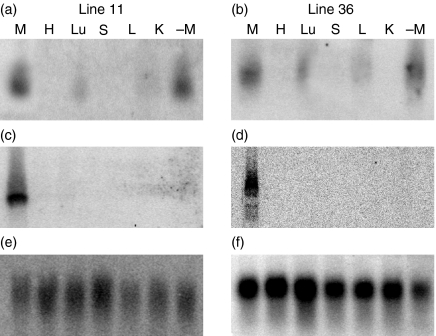

Tissue specificity of bFcRn transgene expression

Tissue specificity of bFcRn α-chain expression (at 8 or 12 days lactation) was determined by Northern blot analysis using total RNA isolated from six different tissues (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and mammary gland). It showed one transcript, which was estimated to be approximately 1·7 kb, only in the mammary gland of the transgenic mice (Fig. 2c,d). This was not unexpected because the bFcRn expression should be under the control of a mammary-gland-specific promoter, β-casein promoter. The size of the detected transcript was consistent with that of the predicted cDNA according to the vector design. Expression of the endogenous mouse FcRn α-chain was mainly detected in the lung and mammary gland (Fig. 2a,b).

Figure 2.

Tissue specificity of the bFcRn transgene expression. Northern blot analysis of total RNA (20 μg per lane) from six different tissues of two transgenic lines: line 11 (mouse 11, F0 generation, day 10 after onset of lactation) and line 36 (mouse 36, F1 generation from line 6, day 12 after onset of lactation). Tissues analysed: H, heart; L, liver; S, spleen; Lu, lung; K, kidney; M, mammary gland; –M, mammary gland of a non-transgenic littermate (day 10). Mouse GAPDH was used as loading control. (a, b) Blots were hybridized with a 1·2-kb mouse FcRn cDNA probe. (c, d) Blots were hybridized with a 6-kb Nco I-digested fragment including part of the promoter and the bovine FcRn α-chain (transgene expression). (e, f) GAPDH hybridizations.

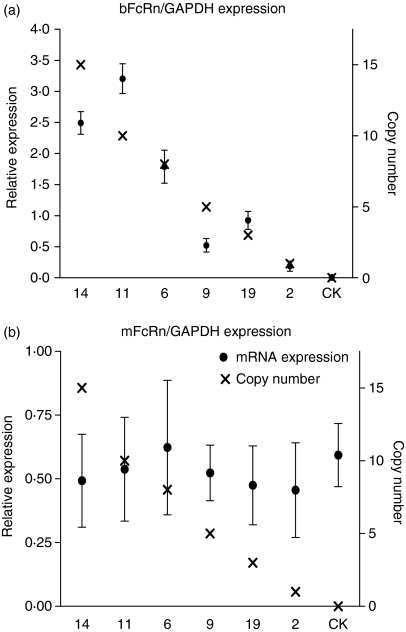

Transgenic mice with a greater copy number of bFcRn transgenes showed higher bFcRn mRNA expression in their mammary gland

Copy numbers of the transgenes were analysed by scanning the signal bands obtained by Southern blot compared to the plasmid control.27 To check the expression levels of the transgenes, total RNA was isolated from the mammary gland of the transgenic F1 female mice at 8–12 days after the onset of lactation. The levels of bFcRn mRNA were measured using quantitative real-time PCR. Both bFcRn and endogenous mFcRn expression levels were determined. As presented in Fig. 3(a), whereas line 2 with one transgene copy per cell exhibited the lowest bFcRn expression level, expression levels of the bFcRn in lines 6, 11 and 14 were markedly higher than those of the endogenous mFcRn (Fig. 3a,b), suggesting that a higher copy number conferred a higher mRNA expression level. Line 6, containing eight copies of transgene per cell, expressed bFcRn at a level approximately three times higher than the endogenous mFcRn, while line 11, containing 10 copies of the transgene, showed approximately six times higher bFcRn expression (Table 2). In the mammary gland of the non-transgenic mice, no bFcRn-specific transcript was detected.

Figure 3.

Bovine FcRn and mouse FcRn mRNA levels (relative to mouse GAPDH expression) in mammary gland during mid-lactation. (a) Relative expression of the bovine FcRn α-chain in different lines measured by quantitative real-time PCR. (b) Relative expression of the mouse FcRn α-chain in these lines. CK, non-transgenic mice; the transgene copy numbers refer only to the bovine FcRn α-chain. Note: As the bovine α-chain could bind the murine β2-chain, we do not know the percentage of heterodimer consisting of the bovine α-chain plus bovine β2-chain in the mammary gland of these transgenic mice.

Table 2.

Transgene expression and IgG concentrations in six bFcRn transgenic lines

| Copy no. | Relative IgG level2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line | bFcRn | bβ2m | RNA levels1 | Milk (μg/ml) | Serum (mg/ml) |

| WT | – | – | – | 127·7 | 0·67 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | + | 152·8 | 0·91 |

| 19 | 3 | – | + + + | 253·1 | 2·43 |

| 9 | 5 | 3 | + + | 158·2 | 1·01 |

| 6 | 8 | 5 | + + + + | 188·7 | 1·41 |

| 11 | 10 | 1 | + + + + | 258·3 | 2·51 |

| 14 | 15 | 10 | + + + + | 262·3 | 2·64 |

Relative RNA levels in mammary gland of the female transgenic mice at 8 or 12 days of lactation are indicated by: +, low; ++, intermediate; ++ +, high and ++ + +, very high.

Total IgG concentrations in milk and serum of the transgenic mice during mid-lactation; the values presented in the table represent mean value of three female mice from each line.

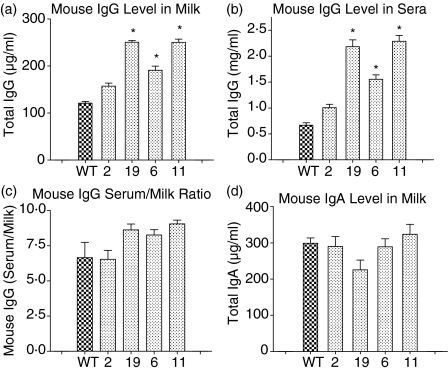

Over-expression of bFcRn in mammary gland resulted in increased IgG levels in both serum and milk of the transgenic mice

Total mouse IgG levels in the milk and sera of the six bFcRn transgenic lines during mid-lactation were measured using ELISA. As shown in Fig. 4 and Table 2, line 2 mice (low bFcRn expression) showed a slightly increased total IgG level compared to non-transgenic mice. In lines 6, 11 and 19, IgG levels in both milk and sera were significantly higher (P < 0·05) than in controls. The increased IgG levels are likely to be ascribed to the expression of bFcRn, which has previously been shown to be able to bind mouse IgG (Imre Kacskovics, unpublished data). To validate this point, we also measured the IgG levels in the male transgenic mice in which bFcRn is not expressed. The results revealed no significant difference in the serum IgG levels between wild-type and transgenic mice (data not shown), strongly supporting the notion that the increased IgG levels resulted from bFcRn expression in the transgenic mice. To check if the effect was specific to IgG, we further measured the IgA levels in the milk of both transgenic and control mice and again found no significant difference. These data suggested that over-expression of the bFcRn in mammary gland led to increased endogenous mouse IgG levels in both serum and milk of the lactating transgenic mice.

Figure 4.

Immunoglobulin levels in serum and milk of bFcRn transgenic mice. IgG (a, b) and IgA (d) levels were determined in milk and serum samples from three mice per line during mid-lactation by sandwich ELISA. Mean values and the standard deviation are shown. WT, control mice; transgenic line number: 2, 19, 6 and 11. (c) The serum : milk ratio of mouse IgG. Significance of P < 0·05 of the statistical analysis (anova) is indicated by an asterisk.

To analyse if the over-expressed bFcRn transported mouse IgG selectively from the serum to milk, we further compared the mouse IgG in serum : IgG in milk ratios in transgenic and control mice. As shown in Fig. 4(c), line 2 mice (low bFcRn expression) showed roughly the same serum : milk IgG ratio as controls. However, the serum : milk IgG ratios in lines 6, 9 and 11 were all significantly higher than in controls, suggesting no unidirectional transport of mouse IgG from serum to milk but rather, a retention of mouse IgG in serum in transgenic mice.

Extended human IgG half-life in the serum of transgenic mice during lactation

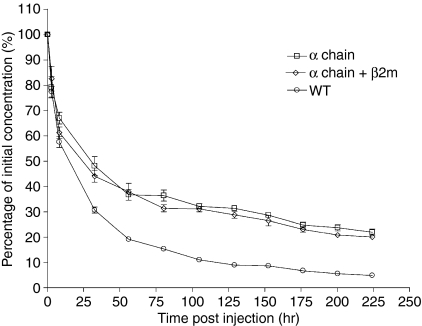

It was recently shown that bFcRn is able to bind human IgG.29 To further validate the theory that over-expressed bFcRn protects the mouse IgG and thus increases its concentration, human IgG tracer antibody was injected into the mice. The clearance curves for human IgG in both transgenic and non-transgenic mice are shown in Fig. 5. The curves are biphasic, with phase α representing equilibration between the intravascular and extravascular compartments and phase β representing the elimination of the protein from the intravascular space. The pharmacokinetic parameters derived from the elimination curves show that human IgG had a longer half-life (both α and β-phase) in transgenic mice than in controls (Table 3), and the areas under the curves (AUC) reflect the calculated values for the half-lives of human IgG in these mice. The half-life of human IgG was 2·9 days in the wild-type animals but increased to 8·5 days (in α-chain-only transgenic mice) and 7·9 days (in both α-chain and β2-chain transgenic mice) in the transgenic mice (Table 3). Human IgG was eliminated more rapidly in wild-type mice than in transgenic mice. There was also a significant difference in IgG clearance in FcRn α-chain-only transgenic mice and transgenic mice containing two bFcRn chains. These experiments clearly showed that expressed bFcRn could prevent the injected human IgG from secretion or catabolism.

Figure 5.

The clearance rate of the injected human IgG in transgenic mice. Human IgG was injected intravenously at 0 hr and blood samples were collected for IgG detection at 0·15, 2·4, 8, 32, 56, 80, 104, 128, 152, 176, 200 and 224 hr after administration. WT indicates wild-type mice; α-chain indicates transgenic mice with only bFcRn α-chain; and α-chain + β2m indicates transgenic mice with double chain.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetics of human IgG in bFcRn transgenic mice

| Half-life (day) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse group | No. of mice | Genotype1 | α-phase | β-phase | AUC (per day)2 |

| WT | 3 | WT | 0·233 ± 0·03 | 2·931 ± 0·105 | 177·89 ± 18·32 |

| α | 3 | α | 0·220 ± 0·121 | 8·547 ± 0·304 | 573·26 ± 96·18 |

| α + β | 3 | α + β | 0·201 ± 0·07 | 7·935 ± 0·415 | 521·26 ± 22·19 |

WT, wild-type mice; α, α-chain integrated mice; α + β, both α-chain and β2m-chain integrated mice.

AUC, area under the curve.

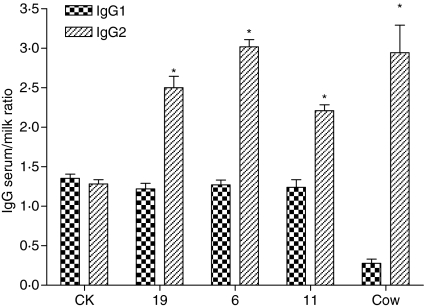

More bovine IgG2 is retained in the serum of transgenic mice

We used the transgenic mice to investigate if over-expressed bFcRn in the mammary gland could selectively increase the transfer of bovine IgG from serum to milk. Bovine IgG (equal amounts of IgG1 and IgG2) was injected intravenously into the mouse tail and their concentrations in milk and serum were measured using ELISA in lines 6, 11 and 19. The serum : milk ratio of the bovine IgG isotype was used as an index for IgG transport. The ratios of bovine IgG1 appeared to be roughly the same in both transgenic mice and controls, suggesting no selective transport of the bovine IgG1 in our transgenic mouse model (Fig. 6). However, the ratios of bovine IgG2 were significantly higher in transgenic mice than in controls, indicating that more IgG2 was retained in the serum of the transgenic mice than in controls (P < 0·05).

Figure 6.

Serum : milk ratios of the injected bovine IgG subclasses in transgenic mice. CK, control mice. The bovine serum : colostrum IgG ratio is according to a previous publication.35 The P-value of the statistical analysis (anova) is indicated.

Discussion

In the present study, we have generated transgenic mice that over-express the bFcRn in their mammary glands during lactation. Using these mice as models, we tried to study if over-expressed FcRn could result in the selective transport of IgG from serum into milk.

We observed significantly higher IgG levels both in serum and milk in the transgenic mice, suggesting that the IgG homeostasis between blood and milk during lactation is perturbed. In cows, bFcRn is hypothesized to be an important candidate receptor in charge of IgG transport during lactation and bFcRn haplotype markers are related to immunoglobulin concentration in milk and calves.17 It has recently also been shown that the bFcRn binds to human IgG more strongly than to bovine IgG, suggesting a cross-species activity that was also previously observed for human and mouse FcRn.28,29 Despite a lack of direct evidence, it might be reasonable to assume that the bFcRn might thus bind to mouse IgG. FcRn is thought to be a saturable IgG receptor30 and more FcRn may bind more pinocytosed IgG and effectively protect more IgG from a degradative fate in lysosomes by transporting it back to the cell surface where, under the influence of neutral pH, it dissociates from the receptor and is free to recycle.31 In the small intestine, milk IgG from the mother will be released at the basolateral surface of intestinal epithelial cells.5 In the mouse mammary gland, FcRn appears to play a role in recycling IgG to maintain constant serum IgG levels during lactation.9

As discussed above, the increase in endogenous murine IgG levels could also be because the serum IgG is prevented from being secreted into milk more effectively because of the over-expression of the bFcRn. To validate this notion, we further investigated the clearance of human IgG in these transgenic mice and clearly showed that the human IgG was prevented from being secreted more effectively and/or degraded more slowly in transgenic mice than in controls. A recent study demonstrated that the bFcRn could bind strongly to human IgG and accordingly, human IgG showed a half-life of 33 days in cattle, which is more than twice as long as that of bovine IgG.29

Interestingly, the transgenic mice containing only the bovine FcRn α-chain also showed increased IgG levels in their serum and milk, suggesting that the bovine FcRn α-chain and mouse β2m may form a functional bovine–mouse chimeric molecule that binds to mouse IgG in vivo. This is in accordance with the high homology of the bovine and mouse β2m and, furthermore, data derived from β2m gene knockout mice have suggested that the FcRn α-chain itself may not bind to IgG.26,31 In BeWo cells, in which the human FcRn α-chain is over-expressed, β2m levels and cellular retention of β2m are increased.32 In our transgenic mice, over-expressed bFcRn α-chain may also retain more mouse β2m to form chimeric FcRn molecules. Increased IgG concentrations in both serum and milk of the transgenic mice should thus be a consequence of over-expression of the bFcRn in their mammary gland.

We did not observe increased transport of mouse IgG from serum to milk during lactation in our transgenic mice in spite of the increased IgG levels in both serum and milk compared to controls. As shown in Fig. 4(c), except for transgenic line 2 (the bFcRn α-chain is expressed at a low level in this line), all the other three transgenic lines exhibited significantly higher IgG serum : milk ratios than controls. It thus seems that over-expression of bFcRn leads to retention of IgG in serum rather than accumulation of IgG in milk. This result is in accordance with a previous observation that IgG subclasses are transferred with an inverse correlation to their binding affinity for FcRn in mice,9 as an enhanced FcRn expression obviously increases the chance for IgG to bind to the FcRn.

Many studies support the notion that IgG transport from serum to colostrum is a highly selective process in cows because in bovine colostrum, the concentration of IgG1 is four or five times higher than in serum. To mimic this process, we injected bovine IgG1 and IgG2 into the transgenic mice to see whether over-expressed bFcRn in the mammary gland would result in selective transport. However, we did not observe accumulation of bovine IgG1 in the milk. In control mice, the serum : milk ratios of bovine IgG1 and IgG2 appeared to be roughly the same as the IgG1 ratios in transgenic mice. However, the ratios of the bovine IgG2 in transgenic mice were significantly higher than in controls. It has previously been suggested that bovine IgG2 has a longer half-life than IgG1, probably reflecting its higher binding affinity to FcRn.33,34 Accepting this hypothesis, the data again suggest that FcRn transports IgG from serum to milk with an inverse correlation with their FcRn binding affinity. On the other hand, it has previously been shown that IgG transfer across the neonatal intestine correlates closely with its affinity for FcRn.3 The latter process may thus be able to compensate for the former, ensuring that the IgG subclass ratio in neonatal serum is roughly similar to that in maternal blood. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms responsible for the differential IgG transfer still require more study. As FcRn–IgG binding is pH dependent, the pH difference in serum, milk and intestine may be a key factor in these processes.

Based on the available data, it is still difficult to understand how bovine IgG1 is selectively transported into the colostrum. As different species utilize different mechanisms to pass their maternal immunity, a comparative study on FcRn expression and its activities in different animals may reveal significant clues for understanding the process of IgG transfer in mammals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Scientific Foundation of China and the Natural Scientific Foundation of Beijing, the Swedish Research council and the National Research Foundation of Hungary (OTKA049015). We thank Li Li Wang and Min Zheng for excellent technical assistance in generation of the transgenic mice. We also thank Chong Liu and Meili Wang for their help with milking the transgenic mice.

References

- 1.Berger M, Novick O. Antibody transfer from mother to fetus. Bibl Gynaecol. 1964;28:30–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elahi S, Buchanan RM, Babiuk LA, Gerdts V. Maternal immunity provides protection against pertussis in newborn piglets. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2619–27. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2619-2627.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghetie V, Ward ES. Multiple roles for the major histocompatibility complex class I-related receptor FcRn. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:739–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kandil E, Noguchi M, Ishibashi T, Kasahara M. Structural and phylogenetic analysis of the MHC class I-like Fc receptor gene. J Immunol. 1995;154:5907–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van de Perre P. Transfer of antibody via mother's milk. Vaccine. 2003;21:3374–6. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller MA, Rodgriguez AL, Alvarez S, Wheeler NC, Reisinger D. Transfer of tuberculin immunity from mother to infant. Pediatr Res. 1987;22:277–81. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198709000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simister NE. Placental transport of immunoglobulin G. Vaccine. 2003;21:3365–9. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breniere S, Viens P. Trypanosoma musculi: transfer of immunity from mother mice to litter. Can J Microbiol. 1980;26:1090–5. doi: 10.1139/m80-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cianga P, Medesan C, Richardson JA, Ghetie V, Ward ES. Identification and function of neonatal Fc receptor in mammary gland of lactating mice. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2515–23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199908)29:08<2515::AID-IMMU2515>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simister NE, Mostov KE. An Fc receptor structurally related to MHC class I antigens. Nature. 1989;337:184–7. doi: 10.1038/337184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhury C, Mehnaz S, Robinson JM, Hayton WL, Pearl DK, Roopenian DC, Anderson CL. The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan. J Exp Med. 2003;197:315–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghetie V, Hubbard JG, Kim JK, Tsen MF, Lee Y, Ward ES. Abnormally short serum half-lives of IgG in beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:690–6. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel EJ, Patel VK, Taylor SF, Marshakrothstein A, Simister N. Requirement for a beta(2)-microglobulin-associated Fc receptor for acquisition of maternal IgG by fetal and neonatal mice. J Immunol. 1995;154:6246–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kacskovics I, Wu Z, Simister NE, Frenyo LV, Hammarstrom L. Cloning and characterization of the bovine MHC class I-like Fc receptor. J Immunol. 2000;164:1889–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer B, Zolnai A, Frenyo LV, Jancsik V, Szentirmay Z, Hammarstrom L, Kacskovics I. Redistribution of the sheep neonatal Fc receptor in the mammary gland around the time of parturition in ewes and its localization in the small intestine of neonatal lambs. Immunology. 2002;107:288–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer B, Doleschall M, Bender B, Bartyik J, Bosze Z, Frenyo LV, Kacskovics I. Expression of the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) in the bovine mammary gland. J Dairy Res. 2005;72:107–12. doi: 10.1017/s0022029905001135. Spec. no. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laegreid WW, Heaton MP, Keen JE, et al. Association of bovine neonatal Fc receptor alpha-chain gene (FCGRT) haplotypes with serum IgG concentration in newborn calves. Mammalian Genome. 2002;13:704–10. doi: 10.1007/s00335-002-2219-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Western AH, Eckery DC, Demmer J, Juengel JL, McNatty KP, Fidler AE. Expression of the FcRn receptor (alpha and beta) gene homologues in the intestine of suckling brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) pouch young. Mol Immunol. 2003;39:707–17. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00260-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stirling CMA, Charleston B, Takamatsu H, Claypool S, Lencer W, Blumberg RS, Wileman TE. Characterization of the porcine neonatal Fc receptor – potential use for trans-epithelial protein delivery. Immunology. 2005;114:542–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.02121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adamski FM, King AT, Demmer J. Expression of the Fc receptor in the mammary gland during lactation in the marsupial Trichosurus vulpecula (brushtail possum) Mol Immunol. 2000;37:435–44. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(00)00065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuroiwa Y, Kasinathan P, Choi YJ, et al. Cloned transchromosomic calves producing human immunoglobulin. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:889–94. doi: 10.1038/nbt727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laird PW, Zijderveld A, Linders K, Rudnicki MA, Jaenisch R, Berns A. Simplified mammalian DNA isolation procedure. Nucl Acids Res. 1991;19:4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kevil CG, Walsh L, Laroux FS, Kalogeris T, Grisham MB, Alexander JS. An improved, rapid Northern protocol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;238:277–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bustin SA. Quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR): trends and problems. J Mol Endocrinol. 2002;29:23–39. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0290023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christianson GJ, Brooks W, Vekasi S, et al. Beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice are protected from hypergammaglobulinemia and have defective antibody responses because of increased IgG catabolism. J Immunol. 1997;159:4781–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu S, Liang M, Fan B, et al. Maternally derived recombinant human anti-hantavirus monoclonal antibodies are transferred to mouse offspring during lactation and neutralize virus in vitro. J Virol. 2006;80:4183–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.4183-4186.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ober RJ, Radu CG, Ghetie V, Ward ES. Differences in promiscuity for antibody–FcRn interactions across species: implications for therapeutic antibodies. Int Immunol. 2001;13:1551–9. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.12.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kacskovics I, Kis Z, Mayer B, et al. FcRn mediates elongated serum half-life of human IgG in cattle. Int Immunol. 2006;18:525–36. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brambell FW, Hemmings WA, Morris IG. A theoretical model of gamma-globulin catabolism. Nature. 1964;203:1352–4. doi: 10.1038/2031352a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Junghans RP, Anderson CL. The protection receptor for IgG catabolism is the beta2-microglobulin-containing neonatal intestinal transport receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5512–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellinger I, Reischer H, Lehner C, Leitner K, Hunziker W, Fuchs R. Overexpression of the human neonatal Fc-receptor alpha-chain in trophoblast-derived BeWo cells increases cellular retention of beta2-microglobulin. Placenta. 2005;26:171–82. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nansen P, Nielsen K. Metabolism of bovine immunoglobulin. I. Metabolism of bovine IgG in cattle with chronic pyogenic infections. Can J Comp Med Vet Sci. 1966;30:327–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Husband AJ, Brandon MR, Lascelles AK. Absorption and endogenous production of immunoglobulins in calves. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1972;50:491–8. doi: 10.1038/icb.1972.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrell HM, Jimenez-Flores R, Bleck GT, et al. Nomenclature of the proteins of cows' milk – sixth revision. J Dairy Sci. 2004;87:1641–74. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]