Abstract

Defecation in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is a readily observable ultradian behavioral rhythm that occurs once every 45–50 s and is mediated in part by posterior body wall muscle contraction (pBoc). pBoc is not regulated by neural input but instead is likely controlled by rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations in the intestinal epithelium. We developed an isolated nematode intestine preparation that allows combined physiological, genetic, and molecular characterization of oscillatory Ca2+ signaling. Isolated intestines loaded with fluo-4 AM exhibit spontaneous rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations with a period of ∼50 s. Oscillations were only detected in the apical cell pole of the intestinal epithelium and occur as a posterior-to-anterior moving intercellular Ca2+ wave. Loss-of-function mutations in the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor ITR-1 reduce pBoc and Ca2+ oscillation frequency and intercellular Ca2+ wave velocity. In contrast, gain-of-function mutations in the IP3 binding and regulatory domains of ITR-1 have no effect on pBoc or Ca2+ oscillation frequency but dramatically increase the speed of the intercellular Ca2+ wave. Systemic RNA interference (RNAi) screening of the six C. elegans phospholipase C (PLC)–encoding genes demonstrated that pBoc and Ca2+ oscillations require the combined function of PLC-γ and PLC-β homologues. Disruption of PLC-γ and PLC-β activity by mutation or RNAi induced arrhythmia in pBoc and intestinal Ca2+ oscillations. The function of the two enzymes is additive. Epistasis analysis suggests that PLC-γ functions primarily to generate IP3 that controls ITR-1 activity. In contrast, IP3 generated by PLC-β appears to play little or no direct role in ITR-1 regulation. PLC-β may function instead to control PIP2 levels and/or G protein signaling events. Our findings provide new insights into intestinal cell Ca2+ signaling mechanisms and establish C. elegans as a powerful model system for defining the gene networks and molecular mechanisms that underlie the generation and regulation of Ca2+ oscillations and intercellular Ca2+ waves in nonexcitable cells.

INTRODUCTION

Genetic model organisms provide a number of powerful experimental advantages for defining the genes and genetic pathways involved in biological processes such as Ca2+ signaling. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is a particularly attractive model system (Barr, 2003; Strange, 2003). C. elegans is well suited for mutagenesis and forward genetic analysis and has a fully sequenced and well annotated genome. Gene expression in nematodes is relatively easy and economical to manipulate using RNA interference (RNAi), knockout, and transgenesis. Genomic sequence as well as many other biological data on this organism are assembled in readily accessible public databases and numerous reagents, including mutant worm strains and cosmid and YAC clones spanning the genome, are freely available through public resources.

C. elegans exhibits a number of relatively simple stereotyped behaviors that have formed the basis for powerful forward genetic screens. The defecation cycle is one such behavior. Defecation is an ultradian rhythm that occurs once every 45–50 s when nematodes are feeding and is mediated by sequential contraction of the posterior body wall muscles, anterior body wall muscles, and enteric muscles (Iwasaki and Thomas, 1997). Posterior body wall muscle contraction (pBoc) appears to be controlled by nonneuronal mechanisms (McIntire et al., 1993; Dal Santo et al., 1999). Loss-of-function mutations in the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) gene itr-1 (also termed dec-4) slow or eliminate (Iwasaki et al., 1995; Dal Santo et al., 1999) the pBoc cycle, whereas overexpression of the gene increases pBoc frequency (Dal Santo et al., 1999). Oscillatory changes in intestinal epithelial cell Ca2+ levels track the defecation cycle with Ca2+ levels peaking just before the initiation of pBoc. Calcium oscillations are slowed or absent in animals with loss-of-function mutations in itr-1 (Dal Santo et al., 1999). Dal Santo et al. (1999) have suggested that IP3-dependent Ca2+ signals may control the secretion of a factor from the intestinal epithelium that regulates contraction of surrounding posterior body wall muscles.

The ability to combine physiological tools such as patch clamp analysis and Ca2+ imaging with behavioral assays and forward and reverse genetic screening provides a powerful approach for defining the molecular details of oscillatory Ca2+ signaling. However, physiological characterization of somatic cells in C. elegans is difficult due to the small size of the animal and the presence of a tough, pressurized cuticle that limits access. The recent development of primary cell culture methods (Christensen et al., 2002) circumvented this problem and has allowed detailed investigation of intestinal cell Ca2+ conductances (Estevez et al., 2003; Estevez and Strange, 2005).

While invaluable for electrophysiological studies, cultured worm intestinal cells do not exhibit spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations (unpublished data). To study oscillatory Ca2+ signaling events directly, we developed an isolated intestine preparation that allows physiological access to the intestinal epithelium. The focus of the current study was to validate the use of the intestine preparation and to begin characterizing the molecular mechanisms of oscillatory Ca2+ signaling. We show here that isolated intestines exhibit spontaneous, rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations that occur with the same frequency as pBoc. Calcium oscillations were only detected in the apical pole of the intestinal epithelium and occur as an intercellular Ca2+ wave that moves in the posterior to anterior direction. Physiological and genetic analyses demonstrate that wave velocity as well as the frequency and rhythmicity of the Ca2+ oscillations require the combined function of PLC γ and β homologues and the IP3R ITR-1. PLC-γ functions primarily to generate IP3 that regulates ITR-1 activity while PLC-β may function to control phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) levels and/or G protein signaling events. The molecular and genetic tractability of C. elegans combined with the physiological accessibility of the isolated intestine preparation and cultured intestinal cells (Estevez et al., 2003; Estevez and Strange, 2005) provides a powerful new model system in which to develop an integrated genetic and molecular understanding of oscillatory Ca2+ signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. elegans Culture and Strains

Nematodes were cultured using standard methods (Brenner, 1974). Wild-type worms were the Bristol N2 strain. The following alleles were used: itr-1(sa73, sy290, sy327), egl-8(n488), ipp-5(sy605), lfe-2(sy326), dgk-1(sy428), dgk-2(gk124), dgk-3(gk110), rde-1(ne219), plc-3(tm1340), and glo-1(zu391). itr-1(sa73) is a temperature-sensitive allele. Worms harboring this mutation were grown at the permissive temperature of 16°C. Approximately 12 h before an experiment, growth temperature was increased to the restrictive temperature of 25°C. All other strains were grown at 25°C.

The C. elegans intestine contains numerous highly autofluorescent lysosomes or “granules.” Where possible, Ca2+ imaging experiments were performed in glo-1(zu391) (gut granule loss) mutant animals. glo-1 encodes a predicted Rab GTPase involved in lysosome biogenesis (Hermann et al., 2005). The number of gut granules and autofluorescence is greatly reduced in glo-1 worms. The characteristics of the defecation cycle and intestinal Ca2+ oscillations and waves were not significantly different in glo-1 versus wild-type N2 worms (not depicted).

Dissection and Fluorescence Imaging of Intestines

Intestines were isolated by placing worms in control saline (137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM glucose, 2 mM l-asparagine, 0.5 mM l-cysteine, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.5 mM l-methionine, 1.6 mM l-tyrosine, 26 mM sucrose, pH 7.3, 340 mOsm) and cutting them behind the pharynx using a 26-gauge needle. The hydrostatic pressure in the worm spontaneously extruded the intestine, which remained attached to the rectum and the posterior end of the animal. Isolated intestines were transferred by pipette to a 35-mm Petri dish with a 14-mm microwell (MatTek Corp.). The bottom of the microwell was covered with a glass coverslip coated with Cell-Tak (BD Biosciences) and the chamber was mounted onto the stage of a Nikon TE2000 inverted microscope. Bath perfusion was performed using an RC-37 35-mm culture dish perfusion chamber insert (Warner Instrument Corp.).

Fluo-4 AM was dissolved in DMSO as a 5 mM stock. Intestines were incubated in the bath chamber for 5–15 min at room temperature in control bath saline containing 1 or 5 μM fluo-4 AM and 1% BSA. Imaging was performed at room temperature (21–22°C) using a Superfluor 20X/0.75 N.A. objective lens or a Superfluor 40X/1.3 N.A. oil objective lens, a Photometrics Cascade 512B cooled CCD camera (Roper Industries) and MetaFluor software (Universal Imaging Corporation). Fluo-4 was excited using a 490-500BP filter, and a 523-547BP filter was used to detect fluorescence emission. Changes in fluo-4 intensity were quantified using region-of-interest selection and MetaFluor software (Universal Imaging Corporation).

Calcium oscillation period, rise time (RT), and fall time (FT) were quantified as described by Prakash et al. (Prakash et al., 1997). Oscillation period is the time between Ca2+ spikes. Rise time is defined as the time to peak fluo-4 fluorescence change after intracellular Ca2+ begins to rise above baseline. Fall time is the time it takes for the peak Ca2+ levels to return to baseline.

Fluorescence images were typically acquired once every 10 s to avoid photobleaching and damage to the intestinal epithelium. However, when Ca2+ wave velocity and Ca2+ spike rise and fall times were quantified, images were acquired once every second over two to three oscillations. The rhythmicity of Ca2+ oscillations in individual intestines was assessed by calculating the coefficient of variance (CV), which is the standard deviation of the Ca2+ spike period expressed as a percent of the mean.

Confocal Microscopy

Intestines were imaged at room temperature (21–22°C) with a Plan-Neofluar 40X/1.3 N.A. oil objective lens on an LSM510-Meta confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). Fluo-4 and GFP were excited with 1–5% nominal power from the 488-nm laser line and fluorescence emission was discriminated with either a 505LP or 505-550BP filter. The confocal z-resolution was set at 1–3 microns. Dynamic range was optimized by setting the detector gain to allow the fluo-4 signal maxima to reach the maximum detector values without going off scale and the detector offset was set to zero. Images were taken at 5-s intervals. Changes in fluo-4 intensity were quantified using region-of-interest selection and thresholding criteria established using negative control background values. Image analysis was performed using MetaMorph (Universal Imaging Corp.).

Characterization of pBoc Cycle

Posterior body wall muscle contraction (pBoc) was monitored at room temperature (21–22°C) in 2-d-old adult worms. Worms were imaged using a Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc. Stemi SV11 M2BIO stereo dissecting microscope (Kramer Scientific Corp.) equipped with a DAGE-MTI DC2000 CCD camera. pBoc rhythmicity in individual worms was assessed by calculating CV as described above.

Brood Assay

Brood size was quantified by transferring L4 larvae to individual plates every 24 h for 4 d at 25°C. The number of progeny on each plate was counted 1 d after eggs hatched.

RNA Interference

RNAi was induced by feeding worms bacteria producing double stranded RNA (dsRNA) to target genes (Kamath et al., 2000). In brief, cDNAs encoding regions of the target gene were obtained by PCR using an oligo dt-primed cDNA library (provided by R. Barstead, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, OK). cDNAs were inserted into vector pPD129.36 using KpnI and Xba1 restriction sites flanked by T7 RNA polymerase promoters. pPD128.110, a derivative of pPD129.36 containing a GFP cDNA, was used as a control in all feeding experiments. HT115(DE3) Escherichia coli were transformed with engineered vectors and fed to worms as described previously (Kamath et al., 2000). The location of cDNAs used for each gene studied were as follows: itr-1, 427–1241 bp; egl-8, 1853–2721 bp; plc-1, 325–1323 bp; plc-3, 1946–3018 bp; plc-2, 362–1447 bp; pll-1, 1430–2368 bp; plc-4, 1312–2219 bp.

Worms were fed egl-8, plc-1, plc-2, plc-4, and pll-1 dsRNAs for two generations beginning at the L1 stage. Because plc-3(RNAi) induces sterility (Yin et al., 2004), L1 worms were fed plc-3 dsRNA for 48 h. rde-1(ne219) and rde-1(ne219);kbEx200 worms were fed egl-8, plc-3, or itr-1 dsRNA for two generations.

Construction of Transgenes and Transgenic Worms

Expression of rde-1 in intestinal cells was driven by a 4-kb sequence upstream of the nhx-2 start codon (provided by K. Nehrke, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY). This sequence was flanked by NheI and NotI restriction sites. Full-length rde-1 genomic DNA was amplified by PCR from wild-type worm DNA using flanking primers containing NotI and SacII restriction sites. A new vector designated pXYY2004.1 was engineered from pPD95.75 (Fire Lab C. elegans Vector Kit; Addgene; http://www.addgene.org/pgvec1?f=c&cmd=showcol&colid=1) by cutting out the GFP coding region using HindIII and EcoRI and inserting a linker containing NheI, NotI, and SacII between these sites. The Pnhx-2::RDE-1 vector was generated by inserting the nhx-2 promoter and rde-1 sequentially into pXYY2004.1. rde-1(ne219) worms were microinjected (Mello et al., 1991) with rol-6 as a transformation marker and Pnhx-2::RDE-1 to generate an extrachromosomal array (kbEx200).

The expression pattern of plc-3 was determined using a transcriptional GFP reporter (termed Pplc-3::GFP). In brief, a vector designated pXYY2004.2 was engineered from pPD95.75 by inserting a NotI restriction site between existing HindIII and BamHI sites. A 4.4-kb plc-3 genomic DNA fragment upstream of the BamHI site in exon 1 was amplified by PCR from wild-type worm DNA and inserted into pXYY2004.2 between NotI and BamHI sites. Transgenic worms were generated by microinjection as described above.

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using Student's two-tailed t test or ANOVA followed by a Tukey-Kramer or Dunn multiple comparisons test. P values of <0.05 were taken to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Intestinal Ca2+ Oscillations

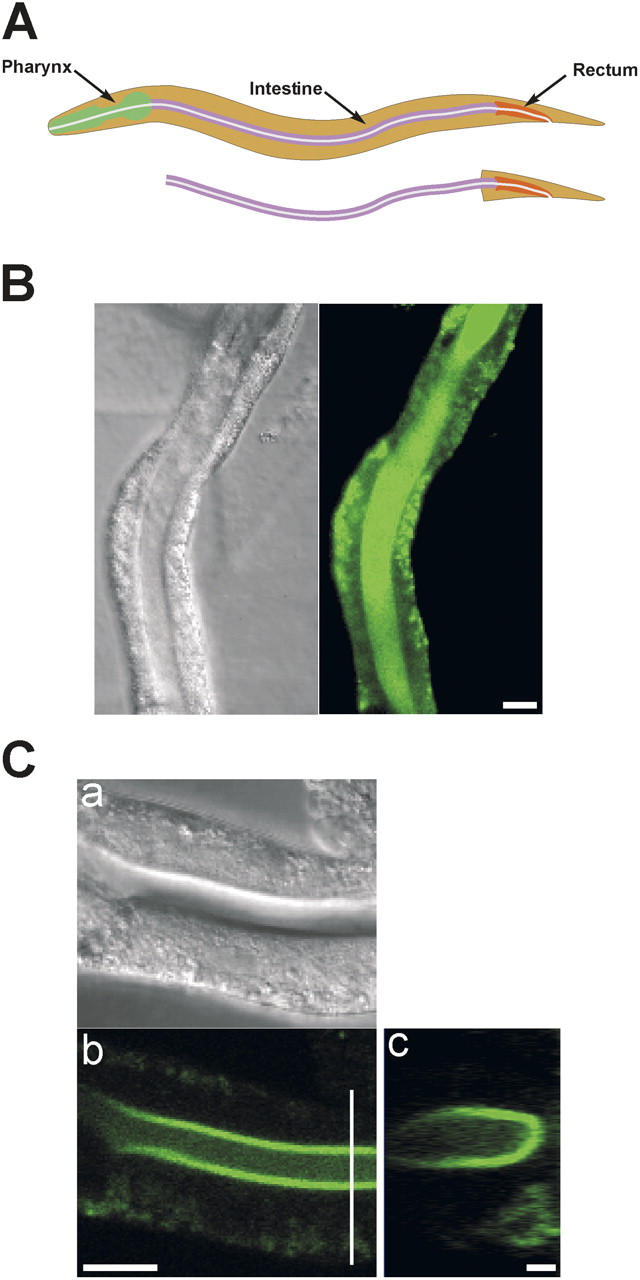

The C. elegans digestive tract consists of a pharynx, intestine, and rectum (Fig. 1 A). The pharynx is a muscular organ that pumps food into the pharyngeal lumen, grinds it up, and then moves it into the intestine. 20 epithelial cells with extensive apical microvilli form the main body of the intestine, which is ∼750 μm long in a full-grown adult worm. Intestinal epithelial cells secrete digestive enzymes, absorb nutrients, and store lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates (White, 1988; Leung et al., 1999; Ashrafi et al., 2003).

Figure 1.

Isolated intestine preparation. (A) Schematic diagrams of worm digestive tract and isolated intestine. (B) Differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence micrographs of an isolated intestine loaded with fluo-4 AM. Bar, 20 μm. (C) DIC and fluorescence confocal micrographs (panels a and b) of an isolated intestine loaded with fluo-4 AM. Panel c is a reconstruction of a series of cross sections. Location of the cross sections is shown by the white vertical line in panel b. Bars in panels b and c are 20 μm and 2 μm, respectively.

Isolated intestines loaded readily with a number of Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent probes. However, probe loading was not uniform. Fluorescence intensity was considerably brighter in the apical pole of the tissue (Fig. 1 B). When viewed by standard widefield fluorescence microscopy, this loading pattern gave the impression that the probe was present in the intestine lumen (e.g., Fig. 1 B).

We used confocal microscopy to characterize the fluorescent probe loading pattern in more detail. Fig. 1 C shows confocal fluorescence and differential interference contrast micrographs of an isolated intestine and a serial reconstruction of a fluorescence Z-series. The fluorescent probe, in this case fluo-4, is clearly present in the intestinal cells and not the intestine lumen. Probe loading is most intense in the apical pole of the cells, which consists of an extensive brush border membrane comprised of numerous microvilli (e.g., Macqueen et al., 2005). The cytoplasm in the basal pole contains a dense network of fat droplets and organelles including yolk granules, endosomes, vacuoles, and lysosomes (White, 1988; Leung et al., 1999; Ashrafi et al., 2003; Hermann et al., 2005). The presence of large numbers of fat droplets and organelles most likely limits the total cytoplasm volume available for probe loading on the basal side of the intestinal epithelium. (The basal pole of the epithelium also loaded intensely with fluo-4 AM when intestines were incubated with the probe for >15 min. However, under these conditions, we were not able to observe Ca2+ oscillations, presumably because of excessive Ca2+ buffering by fluo-4.)

Not all intestines showed Ca2+ oscillations. Oscillations were observed most frequently (∼40% of all intestines studied) in intestines loaded with the acetoxymethyl (AM) ester of fluo-4 (fluo-4, AM). Furthermore, we only detected oscillations in intestines left attached to the rectum and posterior end of the animal (Fig. 1 A). This suggests that complete dissection of the intestine damages posterior intestinal cells that trigger Ca2+ oscillations or that nonintestinal cells secrete an agonist that initiates Ca2+ signaling in the intestinal epithelium.

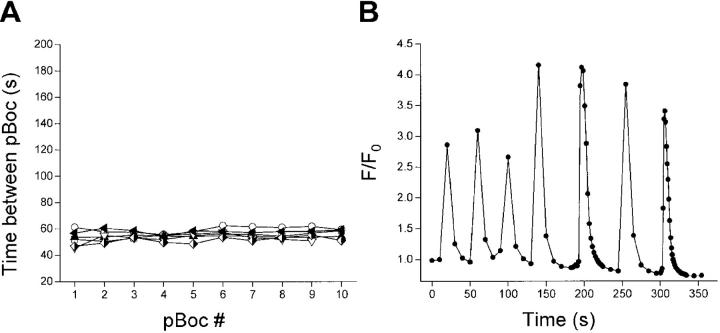

Fig. 2 shows the pBoc cycle in glo-1 worms and an example of typical Ca2+ oscillations in an isolated glo-1 intestine. Under control conditions, the mean Ca2+ oscillation period in glo-1 animals was 49 s, which was not significantly (P > 0.1) different from the mean pBoc period of 55 s (Table I). Both Ca2+ oscillations and pBoc were rhythmic, as indicated by relatively low coefficients of variance (Table I). Mean Ca2+ spike rise and fall times were 8 and 23 s, respectively (Table I).

Figure 2.

pBoc cycle and intestinal Ca2+ oscillations in control (glo-1) worms. (A) Individual pBoc cycles in six glo-1 worms. Data are plotted on an expanded y axis scale to facilitate comparison with pBoc cycles in RNAi and mutant worms strains. (B) Intracellular Ca2+ oscillations in an intestine isolated from a glo-1 worm. Images were acquired at 2- or 10-s intervals. The mean ± SEM Ca2+ oscillation period for this intestine was 48 ± 4 s.

TABLE I.

Characteristics of pBoc and Intestinal Ca2+ Oscillations and Ca2+ Waves in Control Worms (glo-1) and itr-1 Mutants

| Allele | pBoc period | pBoc CV | Ca2+ oscillation period | Ca2+ oscillation CV | Ca2+ oscillation rise time | Ca2+ oscillation fall time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | % | s | % | s | s | |

| glo-1 | 55 ± 1 (6) | 4 ± 1 (6) | 49 ± 3 (6) | 16 ± 1 (6) | 8 ± 1 (5) | 23 ± 3 (5) |

| itr-1(sa73) | 111 ± 10a (6) | 9 ± 3 (6) | 271 ± 30a , b (6) | 24 ± 7 (6) | 17 ± 2a (6) | 30 ± 6 (6) |

| itr-1(sy290) | 49 ± 1 (6) | 4 ± 1 (6) | 50 ± 3 (6) | 10 ± 3 (6) | 6 ± 1 (6) | 17 ± 3 (6) |

| itr-1(sy327) | 53 ± 2 (9) | 8 ± 2 (9) | 42 ± 2 (7) | 11 ± 1 (7) | 5 ± 1 (7) | 20 ± 1 (7) |

Values are means ± SEM (n = number of worms or intestines). Fluorescence images were acquired at 1–10-s intervals.

P < 0.001 compared with glo-1 control animals.

P < 0.002 compared with pBoc in itr-1(sa73) worms.

Calcium oscillations occurred as a Ca2+ wave that began in the distal end of the intestine and proceeded in a posterior-to-anterior direction. Mean Ca2+ wave velocity was 33 μm/s (Table II). Waves traveled 80 ± 3% (n = 10) of the length of the dissected intestine before terminating. Wave velocity was unaffected by rapid perfusion of the extracellular bath against the direction of wave movement (unpublished data) suggesting that wave propagation does not require a paracrine signal released from the basal side of the epithelium. Calcium oscillations continued for up to 2 h after intestines were isolated and exposed to bath perfusion and multiple solution changes.

TABLE II.

Calcium Wave Velocity in Control Worms (N2 and glo-1) and itr-1 Mutants

| Allele | Ca2+ wave velocity | No. of waves observed | No. of waves with velocities too rapid to quantify |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm/s | |||

| N2/glo-1 | 33 ± 3 (10;28) | 30 | 2 |

| itr-1(sa73) | 10 ± 1a (6;16) | 16 | 0 |

| itr-1(sy327) | 64 ± 11b (6;11) | 22 | 11 |

| itr-1(sy290) | 91 ± 16c (5;6) | 13 | 7 |

Values are means ± SEM (n = number of intestines; number of waves). Images were acquired at 1-s intervals.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001 compared with N2/glo-1 control animals.

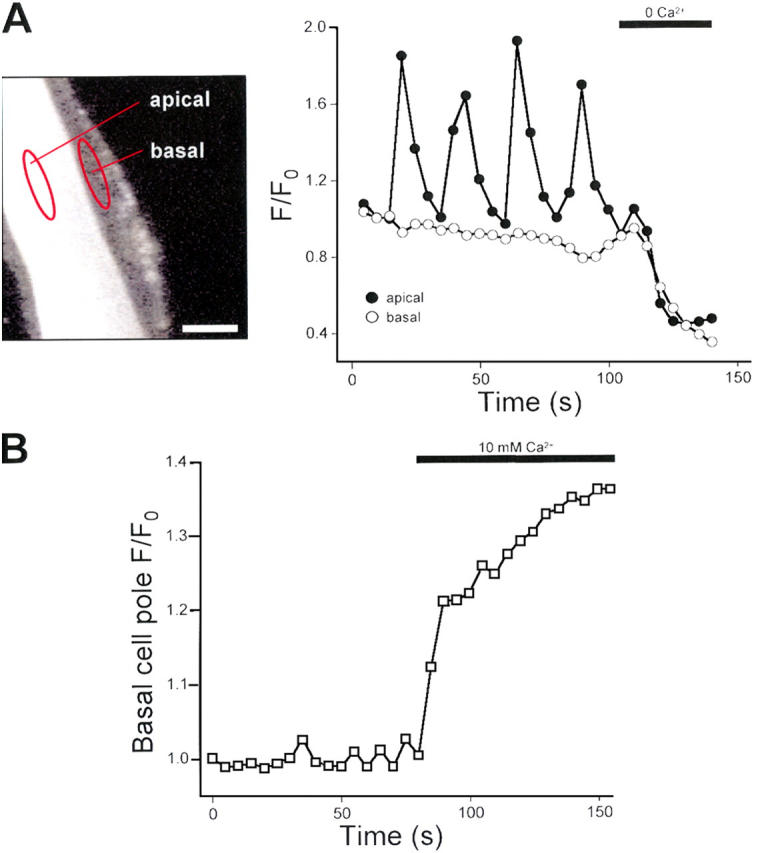

Spatial Localization of Intestinal Cell Ca2+ Oscillations

We used confocal microscopy to determine if Ca2+ oscillations were polarized to apical or basal poles of intestinal cells. A confocal fluorescence micrograph of a fluo-4–loaded intestine is shown in the left panel of Fig. 3 A. The focal plane of the image is located above the apical cell pole at the bottom of the intestine. Two regions of interest are outlined in this image. One region is located in the lumen over the apical membrane and the other in the basal cell pole adjacent to the brush border. Relative changes in fluo-4 intensity are shown in the right panel of Fig. 3 A. Calcium oscillations were detected in the apical pole only.

Figure 3.

Confocal imaging of Ca2+ oscillations in isolated glo-1 intestines. (A, left) Confocal micrograph of a glo-1 intestine loaded with fluo-4 AM. Focal plane is located at the apical pole on the bottom of the intestine. Fluo-4 intensity was quantified in regions of interest outlined in red. One region is located over the apical pole of the intestine. A second region is located in the basal pole adjacent to the apical region. Bar, 10 μm. (A, right) Changes in apical and basal pole fluo-4 intensity. Calcium oscillations are detected only in the apical pole of the epithelium. Removal of extracellular Ca2+ induces similar reductions in fluo-4 intensity in both apical and basal poles. Similar results were obtained in two additional intestines. (B) Effect of elevation of bath Ca2+ on fluo-4 intensity in the basal cell pole. A region of the basal cell pole only was imaged by laser scanning. Elevation of bath Ca2+ to 10 mM induced a rapid rise in basal cell pole fluo-4 fluorescence intensity. Similar results were obtained in two additional intestines.

Given the nonuniform loading of fluo-4, we were concerned that reduced levels of the probe in the basal pole might lead to fluorescence changes that were too small to quantify reliably. To examine this possibility, we removed Ca2+ from the bath. As shown in Fig. 3 A, Ca2+ removal induced a rapid drop in fluo-4 fluorescence. The magnitude of the drop was comparable in the apical and basal poles. Similar results were observed in two other isolated intestines.

Calcium oscillations may not be detected in the basal cell pole if fluo-4 in this region is saturated with Ca2+ and hence unresponsive to cytoplasmic Ca2+ elevation. To test this possibility, we imaged a region of the basal cell pole and monitored the effect of elevation of bath Ca2+ to 10 mM. As shown in Fig. 3 B, the intensity of fluo-4 in the basal cell pole rapidly increased in response to bath Ca2+ elevation. Similar results were observed in two other isolated intestines. Taken together, data in Fig. 3 demonstrate that, while fluo-4 loading is reduced in the basal pole, sufficient free probe is present to detect cytoplasmic Ca2+ changes. These results suggest that Ca2+ oscillations may be polarized to the apical pole of intestinal epithelial cells.

Intestinal Ca2+ Oscillations in itr-1 Mutants

A single gene, itr-1, encodes the IP3R in C. elegans (Baylis et al., 1999; Dal Santo et al., 1999). As discussed previously, itr-1 is required for maintaining normal pBoc rhythm. Consistent with the findings of others (Iwasaki et al., 1995; Dal Santo et al., 1999), we observed that the itr-1 loss-of-function allele sa73 prolonged pBoc cycle time approximately twofold (P < 0.001; Fig. 4 A; Table I). Mean pBoc period was 111 s and was rhythmic, as indicated by a low coefficient of variance (Table I).

Figure 4.

pBoc cycle and intestinal Ca2+ oscillations in itr-1(sa73) loss-of-function worms. (A) Individual pBoc cycles in six itr-1(sa73) worms. (B) Intracellular Ca2+ oscillations in an intestine isolated from an itr-1(sa73) worm. Images were acquired at 10-s intervals. The mean ± SEM Ca2+ oscillation period for this intestine was 314 ± 16 s.

Calcium oscillations in intestines isolated from itr-1(sa73) worms were also rhythmic and prolonged (Fig. 4 B and Table I). The mean Ca2+ oscillation period was 271 s, which was significantly (P < 0.001) different from that observed in control worm intestines. Both Ca2+ oscillation rise time (Table I; P < 0.001) and wave velocity (P < 0.05; Table II) were also slowed significantly compared with control animals.

Interestingly, mean Ca2+ oscillation period was 2.4-fold slower than the pBoc cycle (P < 0.002; Table I). The difference between pBoc period and the Ca2+ oscillation period in isolated sa73 intestines conflicts with the findings of Dal Santo et al. (1999). These investigators demonstrated that Ca2+ oscillations measured in vivo in sa73 worms had a cycle time similar to the pBoc period.

In many cell types, the frequency of IP3-dependent Ca2+ oscillations is modulated by Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane (for review see Shuttleworth and Mignen, 2003). Calcium entry may modulate oscillation frequency by triggering CICR via IP3Rs (for review see Shuttleworth and Mignen, 2003). The sa73 mutation is located in the modulatory region of ITR-1 close to a putative Ca2+ binding domain (Dal Santo et al., 1999). It is conceivable that this mutation alters the sensitivity of the protein to plasma membrane Ca2+ entry, which is influenced by extracellular Ca2+ levels. Thus, the disparity between Ca2+ oscillation frequency observed in vivo (Dal Santo et al., 1999) compared with isolated sa73 intestines could be explained by differences in Ca2+ entry due to differing ionic composition of C. elegans pseudocoelomic fluid, which is unknown, and the saline used to bathe isolated intestines. To test this, we quantified the effect of raising bath Ca2+ from 2 to 4 mM on Ca2+ oscillations. The mean ± SEM oscillation period decreased significantly (P < 0.002) from 166 ± 8 to 62 ± 11 s (n = 5) when extracellular Ca2+ was raised to 4 mM. These results demonstrate that Ca2+ oscillation frequency in the intestinal epithelium is modulated by plasma membrane Ca2+ entry. The differences in Ca2+ oscillation frequency observed in vivo (Dal Santo et al., 1999) and in isolated sa73 intestines are thus likely due to differences in the ionic composition of the pseudocoelomic fluid and bath saline used in our studies.

In addition to sa73, we also examined the effect of the itr-1 gain-of-function alleles, sy290 and sy327, on pBoc and Ca2+ oscillations. pBoc and Ca2+ periods were unaffected by either mutation (Table I). However, as shown in Table II, the velocities of Ca2+ waves were significantly (P < 0.01) increased in both sy290 and sy327 animals. It should be stressed here that the wave velocities reported in Table II are underestimates of the true values. The velocities of 50–54% of the waves observed in intestines of these mutants were too rapid to quantify accurately with our imaging system. In contrast, the velocities of all waves detected in sa73 animals were quantifiable and only 2 out of 30 waves could not be quantified in N2/glo-1 control animals (Table II).

PLC-β and PLC-γ Homologues Regulate Intestinal Ca2+ Oscillations

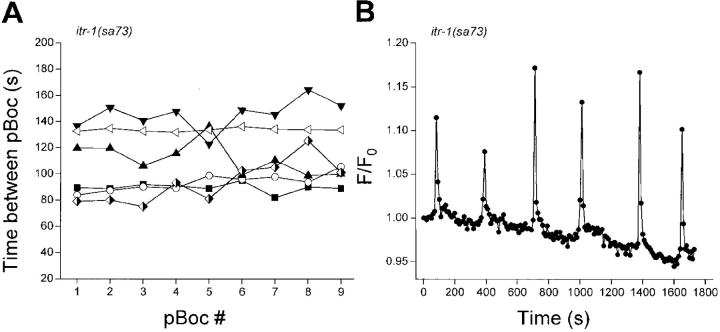

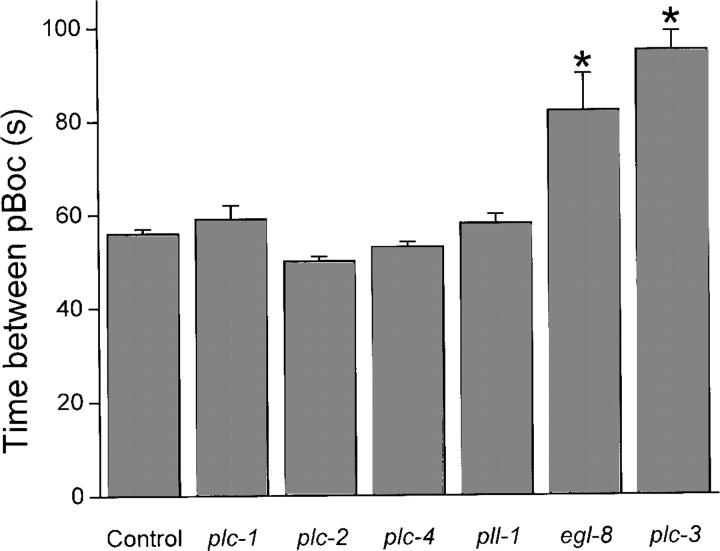

IP3 is generated by PLC-mediated hydrolysis of the membrane lipid PIP2. Six predicted PLC-encoding genes are present in the C. elegans genome: egl-8, plc-1, plc-2, plc-3, plc-4, and pll-1. (pll-1 is the C. elegans homologue of mammalian PLC-like proteins that are catalytically inactive [Kanematsu et al., 1996; Otsuki et al., 1999]. A histidine residue critical for phospholipase activity is mutated in these proteins. The same mutation is present in PLL-1, suggesting that is also catalytically inactive.) Systemic knockdown of gene expression by RNAi can be induced in C. elegans simply by feeding the animals dsRNA-producing bacteria (Kamath and Ahringer, 2003; Kamath et al., 2003; Simmer et al., 2003). To identify the PLCs that regulate pBoc and intestinal Ca2+ oscillations, worms were fed bacteria producing dsRNA homologous to each of the six PLC-encoding genes. As shown in Fig. 5, PLC-1, PLC-2, PLC-4, and PLL-1 RNAi worms had normal pBoc cycles. In contrast, pBoc cycles in EGL-8 and PLC-3 RNAi worms were significantly (P < 0.001) prolonged. egl-8 and plc-3 encode predicted PLC-β and PLC-γ homologues, respectively.

Figure 5.

Effect of PLC RNAi on pBoc period. Worms were fed plc-1, plc-2, plc-4, pll-1, or egl-8 dsRNA for two generations beginning at the L1 stage. RNAi of plc-3 induces sterility (Yin et al., 2004). L1 worms were therefore fed plc-3 dsRNA for 48 h before characterization of pBoc. Values are means ± SEM (n = 8). *, P < 0.001 compared with control worms.

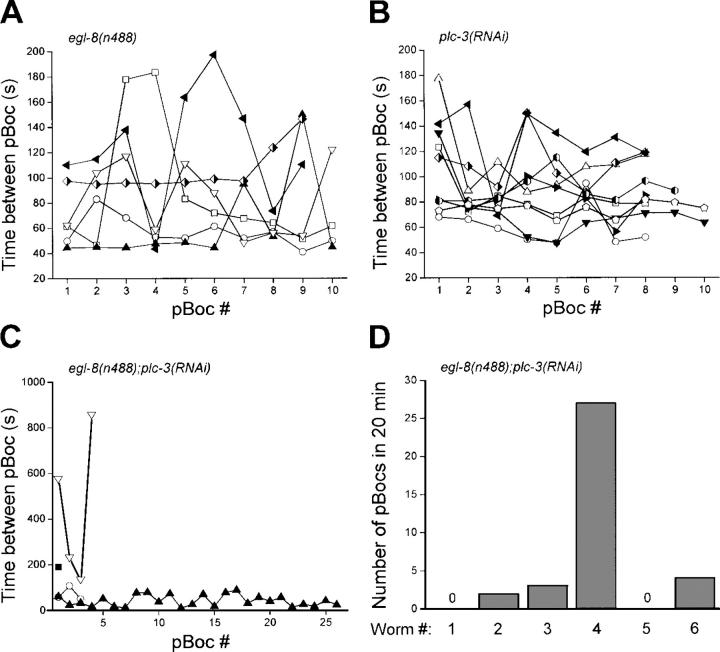

Loss-of-function mutations in egl-8 have been shown previously to disrupt the defecation cycle in C. elegans (Lackner et al., 1999). Fig. 6 shows the effect of the egl-8 loss-of-function allele, n488, and plc-3(RNAi) on pBoc cycles in individual worms. In addition to prolonging cycle time, loss of EGL-8 and PLC-3 activity induces striking pBoc arrhythmia. Mean ± SEM pBoc coefficients of variance for egl-8(n488) and plc-3(RNAi) worms were 38 ± 7% (n = 6) and 22 ± 3% (n = 9). These values were significantly (P < 0.01) different from the mean ± SEM pBoc CV of 6 ± 1% (n = 10) observed in control animals. Worms carrying the plc-3 deletion allele plc-3(tm1340) also exhibited a highly arrhythmic pBoc cycle (mean ± SEM CV = 53 ± 8%; n = 11).

Figure 6.

Effect of egl-8(n488) loss-of-function mutation and plc-3(RNAi) on pBoc rhythm. (A and B) Individual pBoc cycles in egl-8(n488) and plc-3(RNAi) worms. (C and D) pBoc cycles in individual egl-8(n488) worms fed plc-3 dsRNA.

Data in Fig. 6 (A and B) indicate that EGL-8 and PLC-3 both function to maintain a normal pBoc cycle. To determine whether the activities of EGL-8 and PLC-3 are additive, we fed egl-8(n488) mutant worms plc-3 dsRNA. Fig. 6 C shows pBoc cycles measured over a 20-min period in six egl-8(n488);plc-3(RNAi) worms. The phenotype of these worms was considerably more severe than that observed in either egl-8(n488) or plc-3(RNAi) animals (compare Fig. 6, A and B). pBoc was not detected in two of the egl-8(n488);plc-3(RNAi) worms, three of the worms showed one to four pBocs, and one worm exhibited a continuous but highly arrhythmic cycle. The number of pBocs observed in each worm over the 20-min recording period is summarized in Fig. 6 D. Taken together, the results in Fig. 6 demonstrate that pBoc is regulated by both EGL-8 and PLC-3 and that the functions of the two proteins are additive.

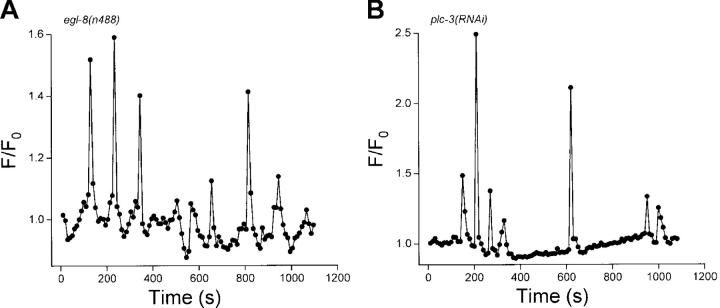

Fig. 7 shows examples of Ca2+ oscillations observed in intestines isolated from egl-8(n488) or plc-3(RNAi) worms. Like pBoc (Figs. 5 and 6), loss of EGL-8 or PLC-3 activity gave rise to Ca2+ oscillation periods that were highly arrhythmic. Calcium oscillations in intestines from egl-8(RNAi) worms showed similar arrhythmia (unpublished data). Mean ± SEM Ca2+ oscillation coefficients of variance were 48 ± 11% (n = 7) (coefficients of variance for Ca2+ oscillations in egl-8(n488) and egl-8(RNAi) worms were not significantly different and were therefore averaged together) and 54 ± 11% (n = 6) for EGL-8 and PLC-3 loss-of-function animals, respectively. These coefficients of variance were significantly (P < 0.01) different from the mean CV of 16% for Ca2+ oscillations observed in intestines of control worms (Table I). The mean ± SEM Ca2+ oscillation CV observed in plc-3(tm1340) worms was 36 ± 4% (n = 4) and was not significantly (P > 0.2) different from that of plc-3(RNAi) animals. Consistent with the severe disruption of pBoc induced by combined loss of EGL-8 and PLC-3 function (Fig. 6, C and D), we were unable to detect Ca2+ oscillations in 40 intestines isolated from egl-8(n488);plc-3(RNAi) worms.

Figure 7.

Calcium oscillations in single intestines isolated from an (A) egl-8(n488) loss-of-function or a (B) plc-3(RNAi) worm. Images were acquired at 10-s intervals.

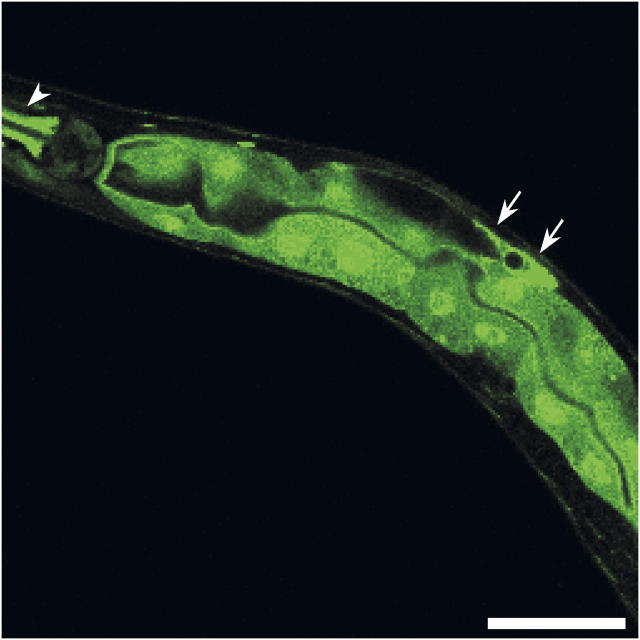

PLC-3 Is Expressed in the Intestine

Previous studies have demonstrated that EGL-8 is expressed in the intestine (Lackner et al., 1999; Miller et al., 1999) and is apparently localized to the apical pole of intestinal epithelial cells (Miller et al., 1999). To determine if PLC-3 is expressed in the gut, we generated transgenic worms expressing a plc-3::GFP transcriptional reporter. As shown in Fig. 8, Pplc-3::GFP was expressed throughout the intestine.

Figure 8.

Confocal fluorescence micrograph of an adult worm showing Pplc-3::GFP expression in the intestine. Strong expression of Pplc-3::GFP was also detected in the spermatheca and gonadal sheath as described previously (Yin et al., 2004; arrows) and the isthmus of the pharynx (arrowhead). Similar observations were made in two independent worms strains. Bar, 50 μm.

EGL-8, PLC-3, and ITR-1 Function in the Intestinal Epithelium

Because it was necessary to leave the posterior end of the animal attached to the intestine (Fig. 1 A), it is conceivable that EGL-8, PLC-3, and/or ITR-1 function in a nonintestinal cell type to regulate Ca2+ oscillations. To address this issue, we exploited the rde-1(ne219) mutation. rde-1 (RNAi defective) encodes a protein involved in translation initiation (Tabara et al., 1999; Fagard et al., 2000) and rde-1 loss-of-function mutants are strongly resistant to RNAi induced by dsRNA injection, feeding, or expression (Tabara et al., 1999). We selectively rescued rde-1 in the intestinal epithelium by generating transgenic worms expressing wild-type rde-1 under the control of the promoter for nhx-2. nhx-2 encodes an intestine-specific Na+/H+ exchanger, and the nhx-2 promoter has been used previously to drive GFP transgene expression selectively in the gut (Nehrke and Melvin, 2002; Nehrke, 2003).

The results of these studies are shown in Table III. pBoc rhythm was normal in rde-1(ne219) mutants fed plc-3 dsRNA, consistent with the defective RNAi response of these worms. In contrast, pBoc was highly arrhythmic in rde-1(ne219);kbEx200 rescued worms fed plc-3 or egl-8 dsRNA. pBoc was also disrupted in rde-1(ne219);kbEx200;itr-1(RNAi) worms.

TABLE III.

Characteristics of pBoc and Intestinal Ca2+ Oscillations in rde-1(ne219) and rde-1(ne219);kbEx200 Worms

| Experiment | Brood size | pBoc period | pBoc CV | Ca2+ oscillation period | Ca2+ oscillation CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. eggs/4 d | s | % | s | % | |

| rde-1(ne219); | 143 ± 16 (5) | 48 ± 2 (6) | 8 ± 1 (6) | ND | ND |

| rde-1(ne219);plc-3(RNAi) | 114 ± 22 (5) | 55 ± 2 (6) | 6 ± 1 (6) | ND | ND |

| rde-1(ne219);kbEx200 | 134 ± 8 (5) | 47 ± 3 (6) | 7 ± 1 (6) | 66 ± 13 (4) | 9 ± 2 (4) |

| rde-1(ne219);kbEx200; plc-3(RNAi) | 122 ± 16 (5) | 75 ± 3a (10) | 27 ± 3b (10) | 52 ± 21 (7) | 29 ± 3b (7) |

| rde-1(ne219);kbEx200; egl-8(RNAi) | ND | 50 ± 9 (6) | 32 ± 2b (6) | 71 ± 12 (4) | 33 ± 2b (4) |

| rde-1(ne219);kbEx200; itr-1(RNAi) | ND | c | c | ND | ND |

Values are means ± SEM (n = number of worms or intestines). Fluorescence images were acquired at 5-s intervals.

P < 0.01 compared with rde-1(ne219);kbEx200 control worms.

P < 0.001 compared with rde-1(ne219);kbEx200 control worms, unfed rde-1(ne219) worms, or rde-1(ne219) worms fed plc-3 dsRNA.

pBoc was analyzed in six rde-1(ne219);kbEx200; itr-1(RNAi) worms. No pBocs were detected in four of the worms during a 20-min observation period. The remaining two worms had relatively normal pBoc cycles. This variability may reflect the presence of mosaicism (e.g., Yochem and Herman, 2003) and/or an incompletely penetrant RNAi effect.

To assess the selectively of the rescue, we monitored brood size. PLC-3 is required for fertility and plc-3(RNAi) worms are sterile (Yin et al., 2004). As shown in Table III, brood size was not significantly (P > 0.05) different in unfed or plc-3 dsRNA-fed rde-1(ne219) or rde-1(ne219);kbEx200 worms. These results indicate that rde-1 has been rescued selectively in the intestine.

Table III also shows data for Ca2+ oscillations in rde-1 rescued worms. rde-1(ne219);kbEx200 worms exhibited rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations, as evidenced by a low coefficient of variance. However, Ca2+ oscillations were arrhythmic in rescued worms fed plc-3 or egl-8 dsRNA. Coefficients of variance were significantly (P < 0.001) greater in rde-1(ne219);kbEx200;plc-3(RNAi) and rde-1(ne219);kbEx200;egl-8(RNAi) worms compared with unfed controls. Taken together, the results in Table III indicate that EGL-8, PLC-3, and ITR-1 function within the intestinal epithelium to control Ca2+ oscillations and pBoc.

EGL-8 and PLC-3 Function in Separate Signaling Pathways

The additive effect of loss of EGL-8 and PLC-3 activity on both pBoc and intestinal Ca2+ oscillations implies that the two enzymes function in separate signaling pathways. However, it is unclear whether the proteins function to coregulate intracellular Ca2+ release via ITR-1. We performed epistasis analysis (Avery and Wasserman, 1992) to determine if EGL-8 and PLC-3 function upstream of ITR-1. Epistasis analysis compares the phenotype of an organism carrying mutations in two separate genes to the phenotype induced by a mutation in a single gene. The ability of one gene mutation to alter the phenotype induced by another mutant gene suggests that the two genes interact in a common pathway (Avery and Wasserman, 1992).

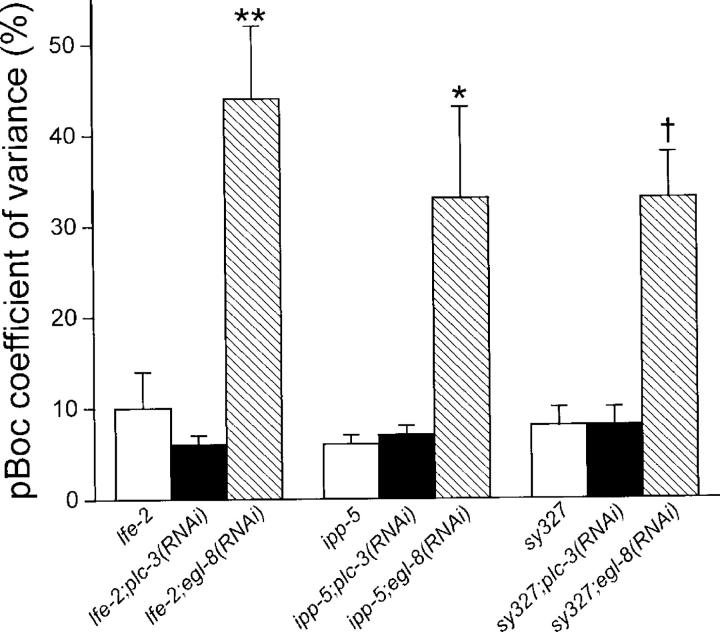

Gain-of-function mutations in itr-1 suppress phenotypes induced by loss of activity in upstream signaling components such as agonists and their receptors, and PLCs (Clandinin et al., 1998; Bui and Sternberg, 2002; Kariya et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2004). We fed itr-1(sy327) gain-of-function worms either egl-8 or plc-3 dsRNA and monitored pBoc rhythmicity. As shown in Fig. 9, itr-1(sy327) fully suppressed the pBoc arrhythmia induced by RNAi of plc-3, but had no effect on egl-8(RNAi)-induced arrhythmia.

Figure 9.

Effect of mutations in ITR-1, the IP3 kinase LFE-2, and the IP3 phosphatase IPP-5 on pBoc arrhythmia (quantified as coefficients of variance) induced by RNAi-mediated loss of EGL-8 or PLC-3 activity. lfe-2(sy326) and ipp-5(sy605) loss-of-function and itr-1(sy327) gain-of-function mutant worms were fed either plc-3 or egl-8 dsRNA. itr-1, lfe-2, and ipp-5 mutations fully suppress arrhythmia induced by plc-3 RNAi (see Fig. 5 B). Values are means ± SEM (n = 6–9). 10 pBoc cycles were measured for each worm. **, P < 0.001 compared with lfe-2 or lfe-2;plc-3(RNAi). *, P < 0.05 compared with ipp-5 or ipp-5;plc-3(RNAi). †, P < 0.001 compared with sy327 or sy327-2;plc-3(RNAi).

lfe-2 and ipp-5 encode an IP3 kinase and phosphatase, respectively (Clandinin et al., 1998; Bui and Sternberg, 2002). Loss-of-function mutations in these genes can suppress phenotypes induced by loss of PLC activity (Kariya et al., 2004), presumably by preventing IP3 conversion into IP4 or IP2 and thereby elevating intracellular IP3 levels. We fed lfe-2(sy326) and ipp-5(sy605) loss-of-function worms egl-8 or plc-3 dsRNA. lfe-2(sy326) and ipp-5(sy605) fully suppressed plc-3 dsRNA-induced arrhythmia, but had no effect on the pBoc arrhythmia induced by loss of EGL-8 activity (Fig. 9).

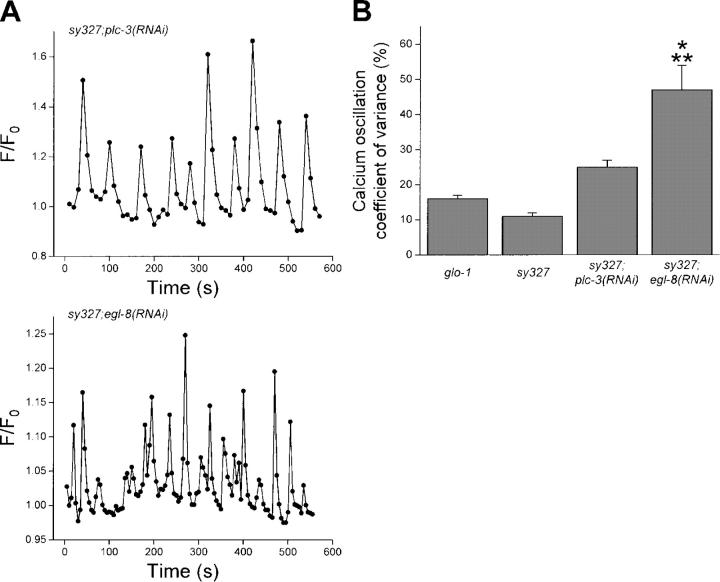

Fig. 10 A shows examples of Ca2+ oscillations in intestines isolated from itr-1(sy327);plc-3(RNAi) and itr-1(sy327);egl-8(RNAi) worms. itr-1(sy327) suppressed the Ca2+ oscillation arrhythmia induced by RNAi of plc-3 but had no effect on egl-8(RNAi). The mean CV for Ca2+ oscillations in itr-1(sy327);plc-3(RNAi) worms was not significantly (P > 0.05) different from that observed in either control glo-1 animals or itr-1(sy327) mutants (Fig. 10 B). In contrast, mean CV for itr-1(sy327);egl-8(RNAi) worms was 47% (Fig. 10 B), which was significantly (P < 0.001) greater than control animals. Taken together, the data in Figs. 9 and 10 indicate that PLC-3 functions to generate IP3 that regulates Ca2+ release from intracellular stores via ITR-1. EGL-8 in contrast appears to function in a separate signaling pathway required for maintaining rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations.

Figure 10.

Effect of itr-1(sy327) gain-of-function mutation on Ca2+ oscillation arrhythmia induced by RNAi-mediated loss of EGL-8 or PLC-3 activity. (A) Calcium oscillations in intestines isolated from a itr-1(sy327);plc-3(RNAi) and itr-1(sy327);egl-8(RNAi) worm. Oscillations are largely normal in the itr-1(sy327);plc-3(RNAi) intestine, but arrhythmic in the intestine isolated from an itr-1(sy327);egl-8(RNAi) worm. (B) Coefficients of variance for Ca2+ oscillations observed in intestines from glo-1, itr-1(sy327), itr-1(sy327);plc-3(RNAi) and itr-1(sy327);egl-8(RNAi) worms. itr-1(sy327) suppresses Ca2+ oscillation arrhythmia induced by RNAi of plc-3, but not arrhythmia induced by egl-8(RNAi). Values are means + SEM (n = 4–7). *, P < 0.001 compared with glo-1 and itr-1(sy327). **, P < 0.01 compared with itr-1(sy327);plc-3(RNAi).

In the C. elegans nervous system, EGL-8 generates diacylglycerol (DAG) that regulates neurotransmission (Lackner et al., 1999; Miller et al., 1999). egl-8 loss-of-function mutations are suppressed by exposure to phorbol esters (Lackner et al., 1999; Miller et al., 1999) and loss-of-function mutation in dgk-1, which encodes a diacylglycerol kinase that converts DAG into phosphatidic acid (Miller et al., 1999). To determine whether EGL-8–mediated DAG signaling regulates intestinal Ca2+ signaling, we treated egl-8(n488) worms for 3 h with 0.1 μM of the phorbol ester PMA. In addition, we characterized the effect of egl-8 RNAi on worms harboring deletion mutations in dgk-1 and the two other predicted C. elegans DAG kinase-encoding genes, dgk-2 and dgk-3.

The pBoc arrhythmia induced by the egl-8 n488 loss-of-function mutation was not suppressed by PMA. Coefficients of variance were not significantly (P > 0.4) different in control and PMA-treated egl-8(n488) worms (Tables II and IV). Deletion mutations in dgk-1, dgk-2, and dgk-3 also failed to suppress the pBoc arrhythmia in egl-8(RNAi) animals (Table IV). Taken together, data in Table IV suggest that EGL-8–generated DAG does not play a significant role in regulating intestinal Ca2+ oscillations.

TABLE IV.

Effect of PMA and Loss of Diacylglycerol Kinase Activity on egl-8(n488)- or egl-8(RNAi)-induced pBoc Arrhythmia

| Experiment | pBoc coefficient of variance (%) |

|---|---|

| egl-8(n488) exposed to 0.1 μM PMAa | 48 ± 8 (6) |

| egl-8(RNAi) | 39 ± 5 (6) |

| dgk-1(sy428) | 12 ± 2 (5) |

| egl-8(RNAi);dgk-1(sy428) | 57 ± 7 (5) |

| dgk-2(gk124) | 7 ± 2 (6) |

| egl-8(RNAi);dgk-2(gk124) | 30 ± 4 (6) |

| dgk-3(gk110) | 14 ± 4b (6) |

| egl-8(RNAi);dgk-3(gk110) | 29 ± 7 (6) |

The frequency of pBoc in egl-8(n488) worms exposed to PMA was severely reduced. pBoc rhythm was therefore quantified over a fixed 20-min observation period. In the six worms examined, two to nine pBocs were detected. For all other worms, pBoc rhythm was quantified over 10 cycles. Values are means ± SEM (n = number of worms).

P < 0.05 compared with N2/glo-1 control animals.

DISCUSSION

C. elegans provides a powerful model system in which to define the genes and molecular mechanisms underlying fundamental biological processes, such as oscillatory Ca2+ signaling. We describe here a novel isolated intestine preparation that allows physiological access to the intestinal epithelium and characterization of intracellular Ca2+ oscillations in wild-type, mutant, and transgenic worms as well as worms in which gene expression has been disrupted selectively by RNAi.

Isolated intestines exhibit spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations (e.g., Fig. 2). Oscillations were only observed in intestines left attached to the rectum and posterior end of the animal (Fig. 1 A), suggesting that oscillations may be triggered by a factor secreted from an unidentified posterior cell type. Alternatively, a pacemaker cell analogous to the interstitial cells of Cajal that regulate rhythmic smooth muscle contraction in the mammalian gut (Camborova et al., 2003) could be located in or adjacent to the posterior end of the intestine and may be responsible for triggering anterior moving Ca2+ waves and oscillations.

Our confocal microscopy studies suggest that Ca2+ oscillations are localized to the apical pole of the intestine (Fig. 3). Polarized Ca2+ signaling has been observed in numerous epithelial cells types (Ashby and Tepikin, 2002). In exocrine glands for example, Ca2+ signals are localized to the apical cell pole where fluid and exocytotic secretion occur (Ashby and Tepikin, 2002).

Dal Santo et al. (1999) proposed that intestinal Ca2+ oscillations induce secretion of a factor at the basal cell pole that induces contraction of the posterior body wall muscles. While speculative, this model raises interesting questions when viewed within the context of our findings. Specifically, how is the apical Ca2+ signal propagated to the basal cell pole? It is possible that a Ca2+ signal at the basolateral cell membrane that is undetectable in our imaging systems regulates secretion of the putative contraction factor. Alternatively, signal propagation could be mediated by apical-to-basal diffusion of second messengers and/or translocation of signaling proteins. Additional genetic and physiological studies are required to determine how intestinal Ca2+ oscillations are triggered and how apical Ca2+ oscillations induce contraction of posterior body wall muscles.

The isolated intestine preparation in combination with primary cell culture methods developed previously by us (Christensen et al., 2002) allows physiological characterization of both intracellular Ca2+ signals as well as ion channel activity that participates in Ca2+ signaling events (Estevez et al., 2003; Estevez and Strange, 2005). A unique aspect of C. elegans is the ability to combine these physiological approaches with powerful forward and reverse genetic screening methods. pBoc is an easily observable and quantifiable behavior that is controlled by intestinal Ca2+ oscillations. Mutagenesis and RNAi screens of pBoc thus allow identification of the genes, gene networks, and molecular mechanisms that underlie intestinal Ca2+ oscillations and waves.

RNAi feeding screens of the six C. elegans predicted PLC-encoding genes demonstrated that EGL-8 and PLC-3, which are homologues of PLC-β and PLC-γ, respectively, function additively in regulating pBoc and intestinal Ca2+ signaling (Figs. 5–7). Epistasis analysis indicated that PLC-3 functions primarily to regulate intracellular Ca2+ release via generation of IP3 (Figs. 9 and 10). The pBoc phenotype (Figs. 5 and 6) induced by loss of PLC-3 activity is similar to that described by Walker et al. (2002). These investigators overexpressed the IP3 binding domain of ITR-1, a protein they termed “IP3 sponge,” in the worm intestine and observed a doubling of the pBoc period and a striking decrease in pBoc rhythmicity. Like loss of PLC-3 activity, overexpression of the IP3 sponge is expected to decrease cellular IP3 levels and disrupt intestinal Ca2+ signaling.

In contrast to PLC-3, the pBoc and Ca2+ oscillation arrhythmia induced by loss of EGL-8 function was not suppressed by a gain-of-function mutation in ITR-1 or loss-of-function mutations in the IP3 kinase or IP3 phosphatase (Figs. 9 and 10). These results suggest that IP3 generated by EGL-8 does not play a significant role in regulating intracellular Ca2+ release. EGL-8 may be localized to a cellular microdomain less accessible to ITR-1 compared with PLC-3 and/or where IP3 is rapidly converted to other lipid metabolites. It is also possible that the rate of IP3 production by EGL-8 may be slow relative to that of PLC-3.

Deletion mutations in either of the three predicted C. elegans DAG kinase-encoding genes or treatment of worms with phorbol ester have no suppressing effect on the pBoc arrhythmia induced by loss of EGL-8 activity (Table IV). These results suggest that DAG generated by EGL-8 may therefore not play a significant role in regulating intestinal Ca2+ signaling events. EGL-8 could function primarily to regulate PIP2 signaling and/or DAG generated by EGL-8 could be metabolized to other signaling molecules such as phosphatidic acid and polyunsaturated fatty acids. PIP2 and DAG metabolites have been shown to regulate several types of ion channels that could mediate or control plasma membrane Ca2+ entry required for intracellular Ca2+ signaling events (e.g., Taylor, 2002; Hardie, 2003; Lei et al., 2003; Chemin et al., 2005). In addition, PIP2 has been shown to regulate the activity of plasma membrane Ca2+ pumps and Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (Hilgemann et al., 2001) that play essential roles in maintaining low resting cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels.

EGL-8 could also function as GTPase activating protein. PLC-β was shown recently to stimulate GTP hydrolysis and G protein signal termination (Mukhopadhyay and Ross, 1999; Cook et al., 2000). Regulation of G protein signaling by EGL-8 could control a variety of cellular functions, including plasma membrane ion channel activity (Wickman and Clapham, 1995) and IP3R gating (e.g., Zeng et al., 2003), that in turn control intestinal Ca2+ signaling events. Ongoing genetic analysis suggests that G protein signaling plays a role in regulating oscillatory Ca2+ signaling in the intestine (Norman et al., 2005; unpublished data).

Random mutagenesis screening and forward genetic analysis provides an unbiased approach for the identification of genes underlying a given phenotype. In addition, forward genetics allows the ordering of genes into pathways and can provide unique insights into protein structure/function (Jorgensen and Mango, 2002). Mutagenesis screening of reproduction in C. elegans has created a wealth of mutants for the study of IP3 signaling. Consistent with the findings of Dal Santo et al. (1999), we observed that pBoc and Ca2+ oscillation period are prolonged in mutant worms expressing the itr-1 loss-of-function allele sa73 (Fig. 4). Importantly, both pBoc and Ca2+ oscillations remain rhythmic in sa73 animals as evidenced by low coefficients of variance (Table I). With few exceptions, we have observed that disruption of numerous other genes that function in intestinal Ca2+ signaling, including plc-3 and egl-8 (e.g., Fig. 6), induces pBoc and Ca2+ oscillation arrhythmia.

The sa73 mutation substitutes tyrosine for cysteine at amino acid residue 1525 (Dal Santo et al., 1999). This mutation lies close to a putative Ca2+ binding domain, suggesting that the increased Ca2+ oscillation period in sa73 worms may be due to reduced ITR-1 Ca2+ sensitivity with subsequent reduction in the rate of channel activation, as suggested previously by Dal Santo et al. (1999). Consistent with this idea, we observed that elevating extracellular Ca2+ from 2 to 4 mM, which presumably increases Ca2+ influx and cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels, decreases Ca2+ oscillation period in sa73 intestines by >2.5-fold.

The itr-1 gain-of-function alleles sy290 and sy327 have no effect on pBoc or Ca2+ oscillation period (Table I). However, both mutations cause a striking increase in the velocity of the posterior-to-anterior Ca2+ wave (Table II). sy290 is an arginine to cysteine substitution at residue 511, which is located in the IP3 binding domain (Clandinin et al., 1998). This mutation increases the in vitro binding affinity for IP3 approximately twofold (Walker et al., 2002). sy327 substitutes leucine 899 with phenylalanine in a putative Ca2+ binding domain (unpublished data).

How sy290 and sy327 affect ITR-1 gating is unknown. Also unknown is how these mutations increase Ca2+ wave velocity but have no effect on Ca2+ oscillation frequency. Gain-of-function is solely a genetic definition that implies no underlying biophysical mechanism. sy290 and sy327 were isolated as dominant mutations that suppress or “rescue” the phenotype induced by loss-of-function mutations in upstream IP3 signaling components (Clandinin et al., 1998). An important determinant of the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations in C. elegans intestinal cells may be the time it takes ITR-1 to recover from inhibition induced by elevated cytosolic Ca2+ levels (e.g., Taylor and Laude, 2002). sy290 and sy327 may have no effect on this recovery process and therefore no effect on oscillation frequency.

One mechanisms by which Ca2+ waves are thought to be propagated between cells is by diffusion of IP3 and/or Ca2+ through gap junctions (Berridge et al., 2000; Rottingen and Iversen, 2000). The sy290 and sy327 mutations may increase Ca2+ wave velocity by increasing the IP3 and Ca2+ sensitivity of ITR-1. By increasing IP3 and Ca2+ sensitivity, less time would be required for diffusion to elevate local IP3 and/or Ca2+ concentrations to levels sufficient for channel activation. Patch clamp analysis of heterologously expressed mutant and wild-type C. elegans ITR-1 using methods described by Foskett and coworkers (Boehning et al., 2001) should allow detailed characterization of channel biophysical properties and correlation with intestinal Ca2+ oscillations and waves. The relative ease and economy of creating transgenic worms also makes it feasible to characterize intestinal Ca2+ signaling in animals expressing mutant IP3Rs that have been engineered with specific gating and regulatory properties.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated for the first time that the isolated C. elegans intestine generates spontaneous rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations. Oscillatory Ca2+ signaling in vitro is regulated by the IP3R ITR-1 and by the combined function of the PLC-γ and PLC-β homologues PLC-3 and EGL-8. PLC-3 functions primarily to generate IP3 and regulate ITR-1 activity, whereas EGL-8 may function to regulate PIP2 levels and/or G protein signaling. The combination of physiological analysis of Ca2+ signaling events in the isolated intestine and ion channel activity in cultured intestinal cells (Estevez et al., 2003; Estevez and Strange, 2005) with molecular biology and forward and reverse genetic analyses of pBoc provides a unique opportunity for elucidation of the gene networks and molecular mechanisms underlying oscillatory Ca2+ signaling in nonexcitable cells.

Acknowledgments

Worm strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN). Confocal microscopy was performed in the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Cell Imaging Shared Resource, which is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants CA68485, DK20593, DK58404, HD15052, and EY08126. We thank Dr. Sam Wells for extensive advice and assistance with confocal microscopy, Rebekah Karns for technical assistance, and Dr. Shohei Mitani (Tokyo Women's Medical University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan) of the National BioResource Project for providing worms carrying the plc-3 deletion allele plc-3(tm1340).

These studies were supported by an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship to M.V. Espelt and by a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellowship and an NIH IRACDA Award (GM#68543) to A.Y. Estevez.

Lawrence G. Palmer served as editor.

Abbreviations used in this paper: AM, acetoxymethyl; CV, coefficient of variance; DAG, diacylglycerol; dsRNA, double stranded RNA; IP3R, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; RNAi, RNA interference.

References

- Ashby, M.C., and A.V. Tepikin. 2002. Polarized calcium and calmodulin signaling in secretory epithelia. Physiol. Rev. 82:701–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi, K., F.Y. Chang, J.L. Watts, A.G. Fraser, R.S. Kamath, J. Ahringer, and G. Ruvkun. 2003. Genome-wide RNAi analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans fat regulatory genes. Nature. 421:268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery, L., and S. Wasserman. 1992. Ordering gene function: the interpretation of epistasis in regulatory hierarchies. Trends Genet. 8:312–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr, M.M. 2003. Super models. Physiol. Genomics. 13:15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylis, H.A., T. Furuichi, F. Yoshikawa, K. Mikoshiba, and D.B. Sattelle. 1999. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors are strongly expressed in the nervous system, pharynx, intestine, gonad and excretory cell of Caenorhabditis elegans and are encoded by a single gene (itr-1). J. Mol. Biol. 294:467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge, M.J., P. Lipp, and M.D. Bootman. 2000. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehning, D., S.K. Joseph, D.O. Mak, and J.K. Foskett. 2001. Single-channel recordings of recombinant inositol trisphosphate receptors in mammalian nuclear envelope. Biophys. J. 81:117–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, S. 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 77:71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui, Y.K., and P.W. Sternberg. 2002. Caenorhabditis elegans inositol 5-phosphatase homolog negatively regulates inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate signaling in ovulation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:1641–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camborova, P., P. Hubka, I. Sulkova, and I. Hulin. 2003. The pacemaker activity of interstitial cells of Cajal and gastric electrical activity. Physiol. Res. 52:275–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemin, J., A. Patel, F. Duprat, M. Zanzouri, M. Lazdunski, and E. Honore. 2005. Lysophosphatidic acid-operated K+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 280:4415–4421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, M., A.Y. Estevez, X.M. Yin, R. Fox, R. Morrison, M. McDonnell, C. Gleason, D.M. Miller, and K. Strange. 2002. A primary culture system for functional analysis of C. elegans neurons and muscle cells. Neuron. 33:503–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin, T.R., J.A. DeModena, and P.W. Sternberg. 1998. Inositol trisphosphate mediates a RAS-independent response to LET-23 receptor tyrosine kinase activation in C. elegans. Cell. 92:523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, B., M. Bar-Yaacov, H. Cohen Ben-Ami, R.E. Goldstein, Z. Paroush, Z. Selinger, and B. Minke. 2000. Phospholipase C and termination of G-protein-mediated signalling in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Santo, P., M.A. Logan, A.D. Chisholm, and E.M. Jorgensen. 1999. The inositol trisphosphate receptor regulates a 50-second behavioral rhythm in C. elegans. Cell. 98:757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez, A.Y., R.K. Roberts, and K. Strange. 2003. Identification of store-independent and store-operated Ca2+ conductances in Caenorhabditis elegans intestinal epithelial cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 122:207–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez, A.Y., and K. Strange. 2005. Calcium feedback mechanisms regulate oscillatory activity of a TRP-like Ca2+ conductance in C. elegans intestinal cells. J. Physiol. 567:239–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagard, M., S. Boutet, J.B. Morel, C. Bellini, and H. Vaucheret. 2000. AGO1, QDE-2, and RDE-1 are related proteins required for post-transcriptional gene silencing in plants, quelling in fungi, and RNA interference in animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:11650–11654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie, R.C. 2003. Regulation of TRP channels via lipid second messengers. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65:735–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, G.J., L.K. Schroeder, C.A. Hieb, A.M. Kershner, B.M. Rabbitts, P. Fonarev, B.D. Grant, and J.R. Priess. 2005. Genetic analysis of lysosomal trafficking in Caenorhabditis elegans Mol. Biol. Cell. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann, D.W., S. Feng, and C. Nasuhoglu. 2001. The complex and intriguing lives of PIP2 with ion channels and transporters. Sci. STKE. 2001:RE19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, K., D.W. Liu, and J.H. Thomas. 1995. Genes that control a temperature-compensated ultradian clock in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:10317–10321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, K., and J.H. Thomas. 1997. Genetics in rhythm. Trends Genet. 13:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, E.M., and S.E. Mango. 2002. The art and design of genetic screens: Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3:356–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, R.S., and J. Ahringer. 2003. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods. 30:313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, R.S., A.G. Fraser, Y. Dong, G. Poulin, R. Durbin, M. Gotta, A. Kanapin, N. Le Bot, S. Moreno, M. Sohrmann, et al. 2003. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 421:231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, R.S., M. Martinez-Campos, P. Zipperlen, A.G. Fraser, and J. Ahringer. 2000. Effectiveness of specific RNA-mediated interference through ingested double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans Genome Biol. 2:2.1-2.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanematsu, T., Y. Misumi, Y. Watanabe, S. Ozaki, T. Koga, S. Iwanaga, Y. Ikehara, and M. Hirata. 1996. A new inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate binding protein similar to phospholipase C-δ1. Biochem. J. 313:319–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariya, K., B.Y. Kim, X. Gao, P.W. Sternberg, and T. Kataoka. 2004. Phospholipase Cɛ regulates ovulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 274:201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner, M.R., S.J. Nurrish, and J.M. Kaplan. 1999. Facilitation of synaptic transmission by EGL-30 Gqα and EGL-8 PLCβ: DAG binding to UNC-13 is required to stimulate acetylcholine release. Neuron. 24:335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Q., M.B. Jones, E.M. Talley, J.C. Garrison, and D.A. Bayliss. 2003. Molecular mechanisms mediating inhibition of G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying K+ channels. Mol. Cells. 15:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung, B., G.J. Hermann, and J.R. Priess. 1999. Organogenesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Dev. Biol. 216:114–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macqueen, A.J., J.J. Baggett, N. Perumov, R.A. Bauer, T. Januszewski, L. Schriefer, and J.A. Waddle. 2005. ACT-5 is an essential Caenorhabditis elegans actin required for intestinal microvilli formation. Mol. Biol. Cell. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire, S.L., E. Jorgensen, and H.R. Horvitz. 1993. Genes required for GABA function in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 364:334–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello, C.C., J.M. Kramer, D. Stinchcomb, and V. Ambros. 1991. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 10:3959–3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K.G., M.D. Emerson, and J.B. Rand. 1999. Goα and diacylglycerol kinase negatively regulate the Gqα pathway in C. elegans. Neuron. 24:323–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, S., and E.M. Ross. 1999. Rapid GTP binding and hydrolysis by Gq promoted by receptor and GTPase-activating proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:9539–9544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehrke, K. 2003. A reduction in intestinal cell pHi due to loss of the Caenorhabditis elegans Na+/H+ exchanger NHX-2 increases life span. J. Biol. Chem. 278:44657–44666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehrke, K., and J.E. Melvin. 2002. The NHX family of Na+-H+ exchangers in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 277:29036–29044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, K.R., R.T. Fazzio, J.E. Mellem, M.V. Espelt, K. Strange, M.C. Beckerle, and A.V. Maricq. 2005. The Rho/Rac family guanine exchange factor VAV-1 regulates rhythmic contractions in C. elegans Cell. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuki, M., K. Fukami, T. Kohno, J. Yokota, and T. Takenawa. 1999. Identification and characterization of a new phospholipase C-like protein, PLC-L2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 266:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, Y.S., M.S. Kannan, and G.C. Sieck. 1997. Regulation of intracellular calcium oscillations in porcine tracheal smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 272:C966–C975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottingen, J., and J.G. Iversen. 2000. Ruled by waves? Intracellular and intercellular calcium signalling. Acta Physiol. Scand. 169:203–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth, T.J., and O. Mignen. 2003. Calcium entry and the control of calcium oscillations. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:916–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmer, F., C. Moorman, A.M. Van Der Linden, E. Kuijk, P.V. Van Den Berghe, R. Kamath, A.G. Fraser, J. Ahringer, and R.H. Plasterk. 2003. Genome-wide RNAi of C. elegans using the hypersensitive rrf-3 strain reveals novel gene functions. PLoS Biol. 1:E12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange, K. 2003. From genes to integrative physiology: ion channel and transporter biology in Caenorhabditis elegans. Physiol. Rev. 83:377–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabara, H., M. Sarkissian, W.G. Kelly, J. Fleenor, A. Grishok, L. Timmons, A. Fire, and C.C. Mello. 1999. The rde-1 gene, RNA interference, and transposon silencing in C. elegans. Cell. 99:123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C.W. 2002. Controlling calcium entry. Cell. 111:767–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C.W., and A.J. Laude. 2002. IP3 receptors and their regulation by calmodulin and cytosolic Ca2+. Cell Calcium. 32:321–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, D.S., N.J. Gower, S. Ly, G.L. Bradley, and H.A. Baylis. 2002. Regulated disruption of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans reveals new functions in feeding and embryogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:1329–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, J. 1988. The anatomy. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans W.B. Wood and the Community of C. elegans Researchers, editors. Cold Srping Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 81–122.

- Wickman, K., and D.E. Clapham. 1995. Ion channel regulation by G proteins. Physiol. Rev. 75:865–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X., N.J. Gower, H.A. Baylis, and K. Strange. 2004. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling regulates rhythmic contractile activity of smooth muscle-like sheath cells in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:3938–3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochem, J., and R.K. Herman. 2003. Investigating C. elegans development through mosaic analysis. Development. 130:4761–4768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, W., D.O. Mak, Q. Li, D.M. Shin, J.K. Foskett, and S. Muallem. 2003. A new mode of Ca2+ signaling by G protein-coupled receptors: gating of IP3 receptor Ca2+ release channels by Gβγ. Curr. Biol. 13:872–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]