Abstract

Fractures of the posterior wall are the most common of the acetabular fractures. The aim of this study was to assess the medium-term results of reconstruction of comminuted posterior wall fractures of the acetabulum by using the buttress technique. This is a retrospective review conducted at a level 1 trauma centre. Thirty-two patients (25 men, 7 women, mean age 41 years, range 14–80 years) with comminuted posterior wall fracture of the acetabulum underwent reconstruction of the posterior wall during the period of July 1998 to February 2004. The average follow-up was 43 months (range 24–70 months). Clinical evaluation was based on modified Merle d’Aubigne and Postel scoring. Radiographic evaluation was according to criteria developed by Matta. The postoperative reduction was graded as anatomical in 28 patients (88%) and imperfect in 4 patients (12%). The clinical outcome was excellent in 11 (34% ), very good in 9 (28%), good in 4 (12%), fair in 3 (9%) and poor in 5 (15%). Radiological grading at the final follow-up was excellent 12 (37%), good 11 (34%), fair 4 (12%) and poor 5 (15%). Reconstruction of comminuted posterior wall acetabular fractures by buttress technique can be expected to produce good results. It can provide a stable fixation of the posterior wall amenable to early range of motion and weight bearing.

Résumé

Les fractures du mur postérieur sont les plus fréquentes des fractures du cotyle. Nous présentons les résultats rétrospectifs à moyen terme, dans un centre de traumatologie de niveau 1, de la reconstruction des fractures comminutives du mur postérieur par la technique de l’étayage. Il y avait 32 patients (25 hommes, 7 femmes, d’âge moyen 41 ans) traités entre Juillet 1998 et Février 2004 avec un recul de 43 mois (24–70). L’évaluation clinique était faite selon les critères modifiés de Merle d’Aubigné et Postel et l’évaluation radiographique selon les critères de Matta. La réduction obtenue était anatomique pour 28 patients (88%) et imparfaite pour 4 (12%). L’évolution clinique était excellente pour 11 patients (34%), très bonne pour 9 (28%), bonne pour 4 (12%), moyenne pour 3 (9%) et mauvaise pour 5 (15%). L’évaluation radiologique au dernier examen était excellente 12 fois (37%), bonne 11 fois (34%), moyenne 4 fois (12%) et mauvaise 5 fois (15%). Cette technique d’étayage permet donc d’obtenir des bons résultats dans les fractures comminutives du mur postérieur. Elle permet une mobilisation et une remise en charge rapide.

Introduction

Fractures of the posterior wall are the most common of the acetabular fractures [1, 2, 9, 15]. They accounted for nearly 47% of the total acetabular fractures in the study by Letournel and Judet [9]. Operative treatment of these fractures has produced varying results by different authors [1, 9, 11, 14, 16, 19, 21]. Though the initial appearance of these fractures appears simple, surgery can be fraught with difficulties if the standard surgical techniques are not adhered to. Most of these fractures are comminuted, thus making it difficult to achieve anatomical reduction [2]. In this study, after reconstructing the posterior wall, the fragments were buttressed by spring plates before being overlapped by a reconstruction plate. The aim of this study is to report the medium-term results of internal fixation of posterior wall fractures by buttress technique.

Materials and methods

A retrospective analysis of posterior wall fractures of the acetabulum was conducted. All fractures were treated by the senior author from July 1998 to February 2004 at a single level 1 trauma centre. A total of 43 patients were identified but only 32 had adequate follow-up. There were 25 males and 7 females, all with unilateral injuries. The right acetabulum was involved in 13 patients while the left was involved in 19 patients. Mean age of patients at the time of injury was 41 years (range of 14–80 years). The inclusion criterion for this study was posterior wall fracture with communition and a minimum follow-up of 2 years (except in three cases of poor clinical outcome where the follow-up was less than 2 years) [17]. The exclusion criteria included (1) open fractures (2) acetabulum fractures operated on for removal of incarcerated fragments without any hardware fixation for the fracture.

The mechanism of injury was as follows: motor vehicle accidents: 25, motorcycle accidents: 3, fall from heights: 2, Pedestrian motor vehicle accidents: 1 and snow board injuries: 1 (this patient was initially managed conservatively at a different hospital, but because of his later instability symptoms, he was referred for surgical intervention).

The associated injuries are presented in Table 1. There were more than two associated injuries in four patients, two injuries in seven patients and single injuries in nine patients. Among the 32 patients, 16 were referred from an outside institution. Posterior dislocation occurred in 20 patients. Seven of them had their hips reduced within 12 h, two patients within 12–24 h of injury and one patient after 24 h. Out of the 10 patients admitted to our hospital with dislocation, 6 of them were reduced within 12 h of injury and 3 of them within 12–24 h of injury and 1 patient after 2 weeks. All hips were reduced closed except for the patient noted at 2 weeks. There were no cases of anterior dislocation. Preoperatively, patients with a history of dislocation were treated with skeletal traction while others were treated with bed rest. The patients were taken up for surgery as soon as their general medical condition permitted. The time from injury to operation averaged 4 days (range of 1–26 days).

Table 1.

Associated injuries

| Type of injury | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Abdomen | 2 |

| Chest | 1 |

| Extremity | 16 |

| Facial | 2 |

| Head | 2 |

| Spine | 1 |

All the patients had standard plain radiographs of the pelvis in three views (anteroposterior and two 45° oblique Judet views) and two-dimensional CT scans preoperatively. Indications for surgery were hip subluxation and >50% involvement of the posterior wall. One gram of IV Cefotaxime was used in the perioperative period. Vancomycin was used in patients having allergies to penicillin.

DVT prophylaxis included Enoxaparin 40 mg daily and IVC filter in those patients having contra-indication to anticoagulation. There were no cases with Morel-Lavalle’ lesions. All the patients were positioned in a lateral position and the acetabulum was approached as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Acetabular exposures

| Type of exposure | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Kocher Langenbeck (KL) | 15 |

| KL with sliding trochanteric osteotomy | 12 |

| Anterior extension of KL with osteotomy | 5 |

Anterior extension and osteotomy were used in those patients where the superior dome could not be visualised using the standard approach. Sliding trochanteric osteotomy was carried out using the upper border of the insertion of the gluteus medius and lower border of origin of the vastus lateralis as two reference points. Two holes were predrilled in the direction of the lesser trochanter to facilitate anatomical reduction later. Extra capsular osteotomy was carried out from a posterior to anterior direction with an oscillating saw, 2–3 mm lateral to the line along the two reference points. The thickness of the osteotomised portion was about 1–1.5 cm. The osteotomised fragment was reattached by two 3.5-mm-cortical screws using the lag technique.

In all the cases, the sciatic nerve was first identified and then protected. Intraoperative nerve monitoring was not used. Femoral head injury was identified in 1 patient. The size of the fragment was very small and was discarded. Marginal impaction of the posterior acetabular wall was present in 10 patients. The impaction was elevated with osteotome and derotated back to its original position. Cancellous bone graft from the greater trochanter was used to fill the defect. Multiple small osteochondral fragments were found in 17 patients.

An attempt was made to anatomically reduce the posterior wall fragments and hold them temporarily with K-wires. One-third semi-tubular plates were used in the form of spring plates by flattening and contouring them into a ‘C’ shape. The end of one of the holes was clipped creating small hooks. These hooks were placed onto the wall fragments and were fixed with screws to the posterior column. The plates were overlapped by a long 3.5 mm reconstruction plate along the posterior column from ileum to ischium. Care was taken to insert screws away from the joint. Intraoperative fluoroscopy was used to confirm the reduction and hardware position.

The distribution of plates used for reconstruction of the fracture is shown in Table 3. The choice regarding the number of plates used depended entirely on the extent of communition of the posterior wall. As the study involved fractures with extreme posterior wall communition not amenable to the lag screw technique, it required multiple plates to achieve a stable reduction. Two reconstruction plates were used in communition with more than one concentric fracture line.

Table 3.

Distribution of plates used for reconstruction of the posterior wall

| Reconstruction plates | Spring plates | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of each plate | Number of patients | |

| 1 | 16 | 2 |

| 2 | 15 | 17 |

| >2 | 1 | 13 |

The average duration of surgery was 2.34 h (range 1.38–3.54 h). Blood loss during the operation averaged 430 ml (range 300–1,400 ml). The average hospital stay was 9 days (range 7–23 days). Heterotopic ossification prevention was used in all patients. Three patients with NSAID intolerance were treated with a single dose of 700 cGy radiation. The remainder were treated with indomethacin 25 mg three times a day for 6 weeks.

Postoperatively all the patients were mobilised as soon as their medical condition permitted. By the second postoperative day, patients were encouraged to sit followed by muscle strengthening and active range of motion exercises. Toe touch weight bearing (10 kg of weight) with help of walkers was permitted. Full weight bearing was started at 3 months. Postoperative reduction was assessed by taking three standard plain radiographs of the pelvis (anteroposterior and two 45° oblique Judet views). A two-dimensional CT scan was not used in all cases. The reduction of fractures was evaluated by measuring the residual displacement in mm. They were graded according to one of the three categories: anatomical (0–1 mm of displacement), imperfect (2–3 mm), and poor (>3 mm).

The follow-up was scheduled at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and annually thereafter. The average follow-up was 43 months (range of 24–70 months). Three patients with poor clinical outcome who had follow-up for less than 2 years were also included in this study.

Clinical and radiological grading was assessed at the final follow-up. Clinical grading was based on Merle d’Aubigne and Postel scoring [12] which has been modified by Matta [11]. According to this clinical grading system, pain, gait, and range of motion of the hip are each assigned a maximum of 6 points. The three individual scores are summed to derive the final score. The clinical result was classified as excellent (18 points), very good (17 points), good (15 or 16 points), fair (13 or 14 points), or poor (<13 points). The radiographs were graded according to the criteria developed by Matta [11]. In this grading method, excellent is given to a normal appearing hip joint, good denotes mild changes with minimal sclerosis and joint narrowing (<1 mm), fair indicates intermediate changes with moderate sclerosis and joint narrowing (<50%) while poor signifies advanced changes. Heterotopic ossification was graded with the use of the classification system by Brooker et al. [3] as modified by Moed and Smith [13]. Avascular necrosis of hips was classified according to the Ficat and Arlet classification [5].

Results

The postoperative reduction was graded as anatomical in 28 patients (88%) and imperfect in 4 patients (12%). The results for clinical outcome according to modified Merle d’Aubigne and Postel scoring system were as follows: excellent 11 ( 34%), very good 9 (28%), good 4 (12%), fair 3 ( 9%) and poor 5 (15%). Figures 1 and 2 show a patient with an excellent functional result. Among the patients presenting with poor outcome, one had severe wear of femoral head, two had infections, one patient had avascular necrosis of the hip, and another had severe post traumatic arthritis.

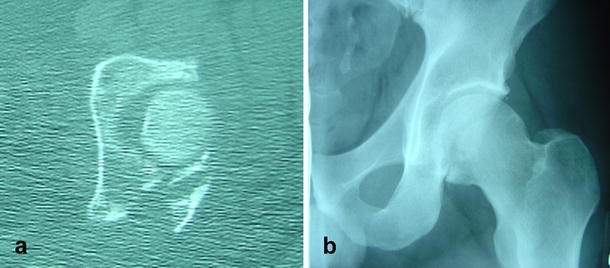

Fig. 1.

a, b Preoperative CT and radiograph of a 43-year-old male with communition of the posterior wall

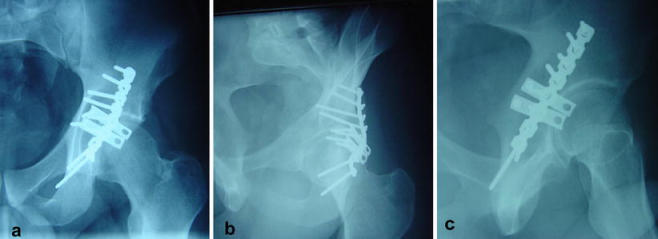

Fig. 2.

a–c At three years of follow up, postoperative radiographs showed an excellent functional result

Among the infected patients, one had intra-articular infection which did not subside with multiple debridements and ultimately had a Girdlestone procedure. This patient also had multiple medical comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, obesity). The other patient had an extra-articular infection which grew MRSA on culture and was treated with vancomycin. He also had multiple debridements and later recovered. Both had poor clinical outcome.

The patient who developed avascular necrosis had dislocation which was reduced operatively after 2 weeks. She developed avascular necrosis, stage 4 according to the Ficat and Arlet classification and was awaiting total hip replacement at the time of this study. Another patient with severe wear of the femoral head underwent THR at 10 months. One patient had a broken spring plate after 67 months of follow-up. He had also developed severe post-traumatic arthritis and was being considered for total hip replacement at the time of the last follow-up.

The latest follow-up x-rays were used for radiological grading according to the criteria developed by Matta. The results were excellent in 12 (37%), good in 11 (34%), fair in 4 (12%) and poor in 5 (15%). Six patients developed heterotopic ossification, of which 4 had class I and 2 had class II; none developed class III or class IV. None of these patients suffered from head injury at the time of initial presentation. Out of five patients who had triradiate incision, two developed heterotopic ossification class I. The patient, whose hip became infected, developed class II ossification. One operation was performed for removal of the symptomatic greater-trochanter hardware.

There were two patients with post-traumatic nerve injury. The sciatic nerve was partially involved in both and the sciatic nerve was identified as contused but intact during operation. Recovery was complete and both had very good clinical outcome. There were no cases of acetabular nonunion, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. All the associated injuries healed without sequelae.

Discussion

Posterior wall fractures, which are the most common of acetabular fractures, are considered easy to address because of ease of access, familiarity with the posterior approach to the hip and the straightforward fixation of an apparently simple fracture pattern. However, results have not been good due to the frequent comminution of the posterior wall (35% in Letournel series) and failure to appreciate marginal impaction. Even achieving anatomical reductions in 94–100% of their cases, Letournel [9] and Matta [11] were able to get excellent to good results in only 68–82%. This difference in outcome has been explained by comminution of the posterior wall, osteonecrosis, marginal impaction and injury to the femoral head. Some recent studies [19] have reported loss of fixation of 30% of cases within the first year of follow-up, while others [4, 14, 16] had excellent to good results in more than 80%.

The spring plates were first used by Mast et al. [10] for communition of the posterior wall. The spring effect is produced by bending the plate into a slightly convex position and as the plate is secured to the posterior column, there is compression of the fragment by the hooks [18].

In the present study, 75% of patients had excellent to good outcome in the medium-term, which is comparable to other studies. The authors postulate that damage to the articular cartilage at the time of initial injury may play an important role in post-traumatic arthritis. Severity of this injury may not be of a high grade so as to cause necrosis of cartilage in the early period, but instead may cause slow degeneration over a longer period of time. This may be the reason for poor outcome even in anatomical reconstruction of the joint when cases are followed for a prolonged period. Further basic science research is needed to assess injury to the cartilage and perhaps predict prognosis, depending upon the severity, if the joint is reconstructed anatomically.

It is important to achieve stable fixation of the wall considering the amount of force delivered to it, especially during the immediate postoperative period and the early part of rehabilitation when range of motion is started. Studies by Goulet et al. [6] have demonstrated that fixation with spring plates and reconstruction plates have a higher load to failure than reconstruction plates alone, especially in concentrically comminuted fractures. Im et al. [7], in their study of 15 patients, used only screws for posterior wall fractures with single fragment or moderate communition. Though they had good results, a description of the exact percentage of communition or the minimum size of the fragments amenable to screw fixation was not reported. They also emphasised that using screws alone can prevent early weight bearing as compared to buttress plate fixation.

Stockle et al. [20], reporting on 45 acetabular fractures treated by 3.5-mm-cortical screws in a lag screw technique achieved excellent to good results in 38 patients. They recommended this technique in acetabular fractures with sufficiently large fragments followed by partial weight bearing at a minimum of 12 weeks. For patients with decreased compliance, osteopenic bone, or comminuted fractures, they suggested using an additional reconstruction plate.

The main indication for using spring plates is communition of the posterior wall, which makes it difficult to use of screws alone. Although the fixation is not as rigid as compared to that of screws, it provides a stable construction to start early range of motion of the hip and weight bearing. There are some limitations to this study. A significant number of patients were lost in follow-up (25%) and their clinical outcome is not known. Correlation between the clinical and radiological outcome and the type/number of plates could not be determined due to the small sample size.

There were six cases (18%) of heterotopic ossification of class 1 and II in our study, which is less than other studies [8, 14] in which prophylaxis was used. This shows the effectiveness of using prophylaxis for heterotopic ossification (HO) especially in triradiate incisions even though statistical significance was not determined because of the small number.

In conclusion, reconstruction of comminuted posterior-wall fractures of the acetabulum via the buttress technique can be expected to produce good results. They can provide a stable fixation of the posterior wall amenable to early range of motion and weight bearing.

References

- 1.Aho AJ, Isberg UK, Katevuo VK (1986) Acetabular posterior wall fracture: 38 cases followed for 5 years. Acta Orthop Scand 57:101–105 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Baumgartner MR (1999) Fractures of the posterior wall of the acetabulum. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 7:54–65 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Brooker AF, Bowerman JW, Robinson RA, Riley LH Jr (1973) Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement: incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am 55:1629–1632 [PubMed]

- 4.Chiu FY, Lo WH, Chen TH, Chen CM, Huang CK, Ma HL (1996) Fractures of posterior wall of acetabulum. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 115:273–275 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Ficat P, Arlet J (1980) Necrosis of the femoral head. In: Hungerford DS (ed) Ischemia and necrosis of bone. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD, pp 53–74

- 6.Goulet J, Rouleau J, Mason D, Goldstein S (1994) Comminuted fractures of the posterior wall of the acetabulum: a biomechanical evaluation of fixate on methods. J Bone Joint Surg Am 76(10):1457–1463 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Im GI, Shin YW, Song YJ (2005) Fractures to the posterior wall of the acetabulum managed with screws alone. J Trauma 58(2):300–303 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kumar A, Shah N, Kershaw S, Clayson A (2005) Operative management of acetabular fractures:a review of 73 fractures. Injury 36(5):605–612 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Letournel E, Judet R (1993) Fractures of the acetabulum. In: Elson RA (ed) Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York

- 10.Mast J, Jakob R, Ganz R (1989) Planning and reduction technique in fracture surgery. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, New York

- 11.Matta JM (1996) Fractures of the acetabulum: accuracy of reduction and results in patients managed operatively within three weeks after the injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am 78:1632–1645 [PubMed]

- 12.Merle d’Aubigne R, Postel M (1954) Functional results of hip arthroplasty with acrylic prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 36:451–475 [PubMed]

- 13.Moed BR, Smith S (1996) Three-view radiographic assessment of heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture surgery. J Orthop Trauma 10(2):93–98 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Moed BR, WillsonCarr SE, Watson JT (2002) Results of operative treatment of fractures of the posterior wall of the acetabulum. J Bone Joint Surg Am 84:752–758 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Olson SA, Finkemeier CG (1999) Posterior wall fractures. Op Tech Orthop 9:148–160 [DOI]

- 16.Pantazopoulos T, Nicolopoulos CS, Babis GC, Theodoropoulos T (1993) Surgical treatment of acetabular posterior wall fractures. Injury 24:319–323 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Reilly MC, Matta JM (1997) The correlation between early radiographic results and long-term clinical outcome following fracture of the acetabulum. Orthop Trans 21:1349

- 18.Richter H, Hutson JJ, Zych G (2004) The use of spring plates in the internal fixation of acetabular fractures. J Orthop Trauma 18(3):179–181 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Saterbak AM, Marsh JL, Nepola JV, Brandser EA, Turbett T (2000) Clinical failure after posterior wall acetabular fractures: the influence of initial fracture patterns. J Orthop Trauma 14:230–237 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Stockle U, Hoffmann R, Nittinger M, Sudkamp NP, Haas NP (2000) Screw fixation of acetabular fractures. Int Orthop 24(3):143–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Wright R, Barrett K, Christie MJ, Johnson KD (1994) Acetabular fractures: long-term follow-up of open reduction and internal fixation. J Orthop Trauma 8(5):397–403 [DOI] [PubMed]