Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate tibiofemoral kinematics after double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstructions and compare them with those of successful single-bundle reconstructions and contralateral normal knees using open MR images. We obtained MR images based on the flexion angle without weight-bearing, from 20 patients with successful unilateral single-bundle (10 patients) and double-bundle (10 patients) ACL reconstructions with tibialis anterior allografts and a minimum 1-year follow-up. The MR images of the contralateral uninjured knees were used as normal controls. Sagittal images of the mid-medial and mid-lateral sections of the tibiofemoral compartments were used to measure the translation of the femoral condyles relative to the tibia. The mean translations of the medial femoral condyles on the tibial plateaus during knee joint motion showed no significant differences among normal, single-bundle, and double-bundle ACL reconstructed knees (all p>0.05). The mean translations of the lateral femoral condyles showed a significant difference between normal and single-bundle reconstructed knees, or between single-bundle and double-bundle reconstructed knees (p<0.05). However, there was no significant difference between normal and double-bundle reconstructed knees (p=0.220). These findings suggest that double-bundle ACL reconstruction restores normal kinematic tibiofemoral motion better than single-bundle reconstruction.

Keywords: Tibiofemoral, Kinematics, Double-bundle, Anterior cruciate ligament, Reconstruction

Résumé

Le but de cette étude était d’évaluer, par les images de résonnance magnétique, la cinématique tibio-fémorale après reconstruction du ligament croisé antérieur par double tunnel et de la comparer avec celle obtenue après réussite des reconstructions à un seul tunnel et celle du genou normal controlatéral. Nous avons étudié des images basées sur l’angle de flexion en décharge chez 20 patients après reconstruction par allogreffe tibiale antérieure suivis au moins un an : 10 avec succés de la reconstruction par un seul tunnel et 10 avec reconstruction par un double tunnel. Les images du genou controlatéral non traumatisé servaient de contrôle. Des images sagittales de la partie moyenne des compartiments fémoro-tibiaux permettaient la mesure de la translation des condyles fémoraux par rapport au tibia. La translation du condyle interne pendant la flexion du genou n’était pas différente entre le genou normal et la reconstruction par simple ou double tunnel (p>0,05). La translation du condyle externe était significativement différente entre le genou normal et la reconstruction par simple tunnel et entre les reconstructions par simple et double tunnel (p<0,05). Cependant il n’y avait pas de différence entre le genou normal et la reconstruction par double tunnel (p=0,220). Ces résultats suggèrent que la reconstruction du croisé antérieur par double tunnel restore mieux la cinématique du genou que la reconstruction par simple tunnel.

Introduction

The primary goal of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is to reduce joint laxity, with the hope of restoring knee stability and normal tibiofemoral kinematics. ACL reconstruction techniques have improved over the last several decades, but improvements in function are achieved with single-bundle ACL reconstruction only by addressing the anteromedial bundle (AMB), which does not reproduce completely the anatomy and function of the ACL. Thus, some patients are not able to return to pre-injury physical activity levels, and they demonstrate a residual pivot shift phenomenon and long-term degenerative changes on radiographs despite successful reconstruction.

Biomechanical studies have demonstrated that standard single-bundle ACL reconstruction successfully restores anteroposterior stability to the knee. However, these techniques involve only AMB reconstruction and are inherently poor at restoring stability in response to a combined rotatory and internal rotation force with valgus torque, such as would occur during a pivot shift [21]. In order to improve knee stability and to approximate the complex biomechanical role of the ACL, several authors have recently proposed an anatomical ACL reconstruction that involves both AMB and posterolateral bundle (PLB) reconstruction [1, 2, 7, 16, 18, 22, 23].

Our hypothesis was that successful double-bundle reconstruction would provide more normal tibiofemoral kinematics than would successful single-bundle reconstructions.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the tibiofemoral kinematics after double-bundle reconstructions and compare them with those of successful single-bundle reconstructions and contralateral normal knees using open magnetic resonance (MR) images.

Materials and methods

We obtained, with consent, MR images from 20 patients with successful unilateral single-bundle (10 patients, group A) and double-bundle (10 patients, group B) ACL reconstructions with tibialis anterior allografts with a minimum 1-year follow-up. The MR images of the contralateral uninjured knees (with no history of a previous injury or subjective complaint) were used as normal controls. Patients with a Lysholm Knee Score > 90 points, side-to-side differences < 3 mm as determined with a Telos device (Telos Stress Device, Austin & Associates, Inc.; Fallston, MD, U.S.A.), and a time period of more than 1 year after ACL reconstruction were included. Patients were excluded if they had an associated meniscal or collateral ligament injury, a symptomatic contralateral knee, symptoms in the ipsilateral hip, ankle or foot, a history of neuromuscular pathology, pain at the time of the initial examination, or grade III or IV radiological degenerative changes.

One surgeon randomly performed both single-bundle and double-bundle arthroscopic ACL reconstruction techniques with tibialis anterior allografts. The femoral side fixation was performed with EndoButton CL® (Smith & Nephew®; Andover, Ma, U.S.A.) and the tibial side fixation was performed with a bioabsorbable interference screw and a staple in all the patients. There were no significant differences between the two groups during the average time from injury to reconstruction and the average follow-up time.

Surgical techniques

The allografts were prepared as two double-looped grafts of more than 12 cm in length and 5–6 mm (PLB) or 7 mm (AMB) in diameter. The graft loop ends were connected to EndoButton CL® with 15 mm (PLB) and 20 mm (AMB) loops, and the free ends were prepared with whip stitches. Standard anterolateral and anteromedial arthroscopic portals were established. In order to prepare the PLB tibial tunnel, an ACL tibial drill guide was placed at the centre of the PL bundle footprint on the tibia (5–7 mm anterior to the PCL) just anterior to the superficial medial collateral ligament fibres at a set angle of 55°. The AMB tunnel was positioned in a more anteromedial position on the tibial footprint (7 mm anterior and 5 mm medial to the PL tunnel) using the tibial drill guide set at an angle of 45°, with a starting point on the tibial cortex, which was more anterior and central than the PL tunnel. The AM femoral tunnel through the AM portal was prepared at the 1:00 o’clock position on the left or at the 11:00 o’clock position on the right. The PL femoral tunnel was drilled through an accessory AM portal at 5–8 mm anterior to the posterior femoral articular surface. The grafts for the PL and AM bundles were then passed through and the EndoButton loop was flipped over the anterolateral femoral cortical surface in order to establish a femoral fixation. The knee was then cycled through a full range of motion approximately ten times. The PL graft was fixed, first with the knee in 10–20° of flexion, and then the AM graft was fixed at 60–70° of flexion with bio-absorbable interference screws, BioScrew® (Linvatec®; Largo, Fl, U.S.A.). One ligament staple was used for additional graft fixation on the tibial side.

The single-bundle ACL reconstructions with tibialis anterior allografts of 8–9 mm in diameter were performed in the usual manner (AMB reconstruction) and graft fixation material was the same as that described above for the AMB reconstructions at the nearly full extension position of the knee.

Postoperative rehabilitation

All the patients followed the same post-operative rehabilitation protocol. Range of motion exercises were started immediately after surgery. Partial weight-bearing with crutches was allowed within several days of surgery and was gradually increased to tolerable weight-bearing by the first week. Quadriceps muscle strengthening exercises during the early post-operative phase was performed mainly with closed kinetic chain exercises. Return to sporting activities was allowed 6 months after surgery.

Kinematic study

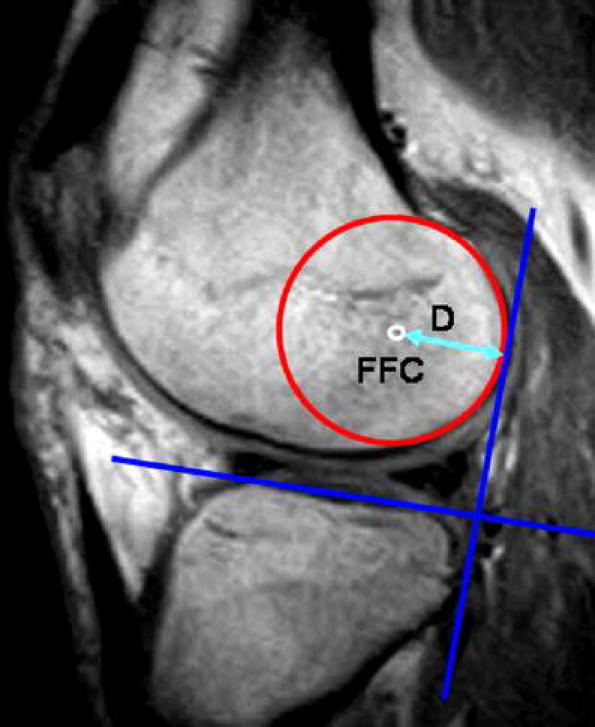

All the patients were scanned with an open MR system (0.3T, AIRIS®, Hitachi®; Tokyo, Japan). MR T1-weighted images were taken with the patients in a non-weight bearing decubitus position with the knees in extension and at 30°, 60°, 90°, and 120° of flexion. Sagittal images of the mid-medial and mid-lateral sections of the tibiofemoral compartments were used to measure the locations of the posterior femoral condyles relative to the tibia [10]. The centres of the posterior circular surfaces of the femoral condyles were identified, and the distances between these flexion facet centers (FFC) and a vertical line drawn from the posterior tibial cortices were measured for each position and were corrected for magnification (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Measurement of distance (d) from a flexion facet centre (FFC) to the posterior tibial cortex

The kinematic data for normal, single-bundle, and double-bundle ACL reconstructed knees were compared using the Mann--Whitney test (SPSS for Window Release 11.0, SPSS®, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

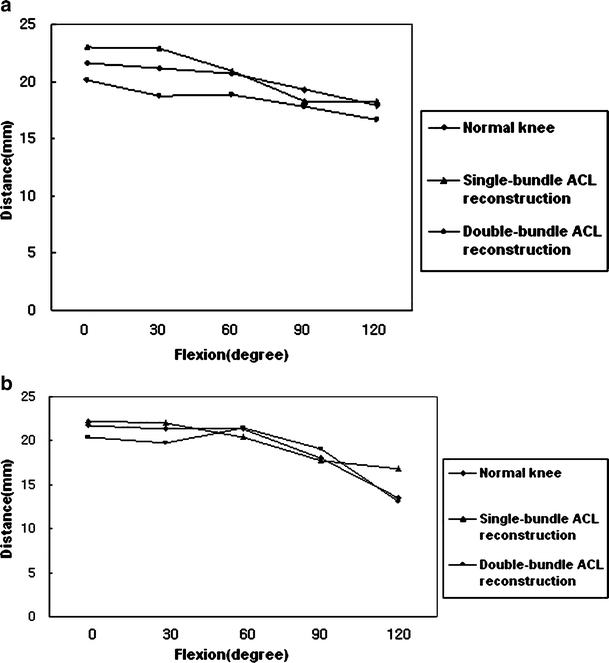

In the medial compartments, the mean distances between the FFCs and the posterior tibial cortices at 0° of extension in normal, single-bundle, and double-bundle ACL reconstructed knees, were 21.6, 23.0, and 20.2 mm, respectively; and at 120° of knee flexion these distances were 17.9, 18.3, and 16.7 mm, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 2a). In the lateral compartments, the mean distances between the FFCs and the posterior tibial cortices at 0°of extension in normal, single-bundle, and double-bundle ACL reconstructed knees, were 21.7, 22.3, and 20.4 mm, respectively; and at 120° of knee flexion these distances were 13.5, 16.8, and 13.1 mm, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 2b).

Table 1.

The position of the flexion facet centre relative to the posterior tibial cortex in the medial tibiofemoral compartment (mm)

| 0° | 30° | 60° | 90° | 120° | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal knee | 21.6 | 21.2 | 20.7 | 19.3 | 17.9 |

| Single-bundle reconstruction | 23.0 | 22.9 | 20.9 | 18.3 | 18.3 |

| Double-bundle reconstruction | 20.2 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 17.9 | 16.7 |

Fig. 2.

The position of a flexion facet centre relative to the posterior tibial cortex in the medial (a) and lateral (b) tibiofemoral compartments during knee joint motion

Table 2.

The position of the flexion facet center relative to the posterior tibial cortex in the lateral tibiofemoral compartment (mm)

| 0° | 30° | 60° | 90° | 120° | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal knee | 21.7 | 21.3 | 21.3 | 18.0 | 13.5 |

| Single-bundle reconstruction | 22.3 | 22.0 | 20.4 | 17.8 | 16.8 |

| Double-bundle reconstruction | 20.4 | 19.8 | 21.5 | 19.0 | 13.1 |

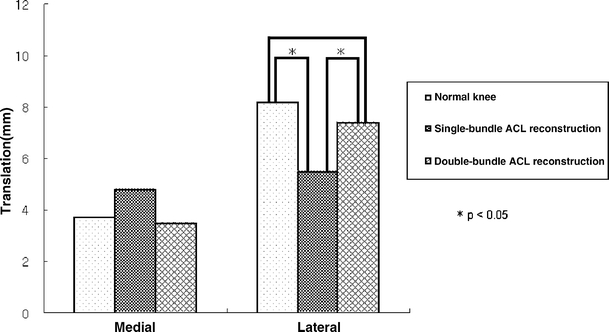

The mean translations of the medial flexion facet centres on the tibial plateaus during knee joint motion from 0° to 120° in normal, single-bundle, and double-bundle ACL reconstructed knees, were 3.7, 4.8, and 3.5 mm, respectively. There were no significant differences observed between the knees in terms of the extent of excursion of the femurs posteriorly on the tibias (normal vs. single-bundle reconstructed, p=0.551; normal vs. double-bundle reconstructed, p=0.979; and single-bundle vs. double-bundle reconstructed, p=0.579).

The mean translations of lateral flexion facet centres on the tibial plateaus during knee joint motion from 0° to 120° in normal, single-bundle, and double-bundle ACL reconstructed knees, were 8.2, 5.5, and 7.4 mm, respectively. There were significant differences between normal and single-bundle reconstructed knees (p=0.001), and between single-bundle and double-bundle reconstructed knees (p=0.023); but there was no significant difference between normal and double-bundle reconstructed knees in this respect (p=0.220) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The translation of the femoral condyles on the tibial plateaus during knee joint motion from 0° to 120° in normal, single-bundle, and double-bundle ACL reconstructed knees * Indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) when compared with each other

Discussion

Anatomically, the ACL can be divided into two functional bundles: the anteromedial (AM) and posterolateral (PL) bundles [5]. The AM bundle appears to be an important stabiliser against anteroposterior loads, particularly when a knee is flexed by more than 15°; whereas, the PL bundle provides additional anteroposterior knee stability when the knee is in the near-extended position [20]. Moreover, both the AM and PL bundles provide significant stabilisation against rotatory loads [20]. Cadaveric studies indicate that double-bundle ACL reconstruction may restore knee biomechanics more closely to normal than do single-bundle ACL reconstruction, and that it may provide better rotational stability of the knee joint [22]. Moreover, in vivo studies demonstrate that even though single-bundle ACL reconstruction may restore anteroposterior knee stability, it does not restore knee joint rotational stability, and therefore, cannot restore normal knee kinematics [6].

In the clinical setting, different surgical techniques restoring the AM and PL bundles have been described. Recently, there have been reports of superior results of double-bundle reconstruction with respect to Lachman’s test and the pivot shift phenomenon compared with single-bundle reconstruction [17, 24]. However, there have been no reports about the in vivo kinematics of double-bundle ACL reconstructed knees. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first kinematic study that has been performed in vivo.

Relative tibiofemoral motions medially and laterally were found to be markedly different, as previously described [9, 10, 13, 14]. The medial femoral condyles were found to have less relative movement on the tibias and anteroposterior roll back from extension to 120° of flexion compared with the lateral compartments. Whereas, the lateral femoral condyles moved posteriorly more than the medial femoral condyles did on the lateral tibias during flexion and much more roll back occurred. In this study, although the medial femoral condyles moved posteriorly from full extension to 120° of flexion in all the groups, there were no significant differences between single-bundle and normal knees, or between double-bundle reconstructed and normal knees.

However, there were significant differences between normal and single-bundle reconstructed knees, and single-bundle and double-bundle reconstructed knees with respect to posterior movement of the lateral femoral condyles. There was no significant difference between normal and double-bundle reconstructed knees.

In conclusion, the posterior translation of the lateral femoral condyles in the double-bundle reconstructed knees was closer to the translation in the normal knees than in the single-bundle reconstructed knees. These findings suggest that double-bundle ACL reconstruction restores kinematic tibiofemoral motion to near normal better than single-bundle reconstruction.

However, this kinematic study with MR imaging data has a limitation: it is a non-weight bearing, static study, rather than a weight-bearing dynamic study, which would have been ideal. Therefore, further long-term clinical and dynamic kinematic studies after double-bundle ACL reconstructions are necessary in order to achieve general acceptance as an improved method of ACL reconstruction.

References

- 1.Adachi N, Ochi M, Uchio Y, Iwasa J, Kuriwaka M, Ito Y (2004) Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Single- versus double-bundle multistranded hamstring tendons. J Bone Joint Surg 86–B:515–520 [PubMed]

- 2.Bellier G, Christel P, Colombet P, Djian P, Franceschi JP, Sbihi A (2004) Double-stranded hamstring graft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 20:890–894 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bonnin M, Carret JP, Dimnet J, Dejour H (1996) The weight-bearing knee after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. An in vitro biomechanical study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 3:245–251 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, Fithian DC, Rossman DJ, Kaufman KR (1994) Fate of the ACL-injured patient: a prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med 22:632–644 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dienst M, Burks RT, Greis PE (2002) Anatomy and biomechanics of the anterior cruciate ligament. Orthop Clin North Am 33:605–620 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gabriel MT, Wong EK, Woo SL, Yagi M, Debski RE (2004) Distribution of in situ forces in the anterior cruciate ligament in response to rotatory loads. J Orthop Res 22:85–89 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Hamada M, Shino K, Horibe S, Mitsuoka T, Miyama T, Shiozaki Y, Mae T (2001) Single- versus bi-socket anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autogenous multiple-stranded hamstring tendons with endoButton femoral fixation: A prospective study. Arthroscopy 17:801–807 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Harter RA, Osternig LR, Singer KM, James SL, Larson RL, Jones DC (1988) Long-term evaluation of knee stability and function following surgical reconstruction for anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency. Am J Sports Med 16:434–443 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hill PF, Vedi V, Williams A, Iwaki H, Pinskerova V, Freeman MA (2000) Tibiofemoral movement 2: the loaded and unloaded living knee studied by MRI. J Bone Joint Surg 82-B:1196–1198 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Iwaki H, Pinskerova V, Freeman MA (2000) Tibiofemoral movement 1: the shapes and relative movements of the femur and tibia in the unloaded cadaver knee. J Bone Joint Surg 82-B:1189–1195 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kaplan MJ, Howe JG, Fleming B, Johnson RJ, Jarvinen M (1991) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using quadriceps patellar tendon graft. Part II. A specific sport review. Am J Sports Med 19:458–462 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Laxdal G, Kartus J, Hansson L, Heidvall M, Ejerhed L, Karlsson J (2005) A prospective randomized comparison of bone-patellar tendon-bone and hamstring grafts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 21:34–42 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Logan M, Dunstan E, Robinson J, Williams A, Gedroyc W, Freeman M (2004) Tibiofemoral kinematics of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)-deficient weightbearing, living knee employing vertical access open "interventional" multiple resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med 32:720–726 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Logan MC, Williams A, Lavelle J, Gedroyc W, Freeman M (2004) Tibiofemoral kinematics following successful anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using dynamic multiple resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med 32:984–992 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Mannel H, Marin F, Claes L, Durselen L (2004) Anterior cruciate ligament rupture translates the axes of motion within the knee. Clin Biomech 19:130–135 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Marcacci M, Molgora AP, Zaffagnini S, Vascellari A, Iacono F, Presti ML (2003) Anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstrings. Arthroscopy 19:540–546 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Muneta T, Koga H, Morito T, Yagishita K, Sekiya I (2006) A retrospective study of the midterm outcome of two-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using quadrupled semitendinosus tendon in comparison with one-bundle reconstruction. Arthroscopy 22:252–258 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Muneta T, Sekiya I, Yagishita K, Ogiuchi T, Yamamoto H, Shinomiya K (1999) Two-bundle reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament using semitendinosus tendon with Endobuttons: Operative technique and preliminary results. Arthroscopy 15:618–624 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Sernert N, Kartus J, Kohler K, Stener S, Larsson J, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J (1999) Analysis of subjective, objective and functional examination tests after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A follow-up of 527 patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 7:160–165 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Tashman S, Collon D, Anderson K, Kolowich P, Anderst W (2004) Abnormal rotational knee motion during running after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 32:975–983 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Woo SL, Kanamori A, Zeminski J, Yagi M, Papageorgiou C, Fu FH (2002) The effectiveness of reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with hamstrings and patellar tendon. A cadaveric study comparing anterior tibial and rotational loads. J Bone Joint Surg 84-A:907–914 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Yagi M, Wong EK, Kanamori A, Debski RE, Fu FH, Woo SL (2002) Biomechanical analysis of an anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 30:660–666 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Yasuda K, Kondo E, Ichiyama H, Kitamura N, Tanabe Y, Tohyama H, Minami A (2004) Anatomic reconstruction of the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles of the anterior cruciate ligament using hamstring tendon grafts. Arthroscopy 20:1015–1025 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Yasuda K, Kondo E, Ichiyama H, Tanabe Y, Tohyama H (2006) Clinical evaluation of anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction procedure using hamstring tendon grafts: comparisons among 3 different procedures. Arthroscopy 22:240–251 [DOI] [PubMed]