Introduction

Oral mucositis refers to erythematous and ulcerative lesions of the oral mucosa observed in patients with cancer being treated with chemotherapy, and/or with radiation therapy to fields involving the oral cavity. Lesions of oral mucositis are often very painful and compromise nutrition and oral hygiene as well as increase risk for local and systemic infection. Mucositis can also involve other areas of the alimentary tract; for example, gastrointestinal (GI) mucositis can manifest as diarrhea. Thus, mucositis is a highly significant and sometimes dose-limiting complication of cancer therapy 1, 2.

Epidemiology of Mucositis

Oral mucositis is a significant problem in patients undergoing chemotherapeutic management for solid tumors. In one study, it was reported that 303 of 599 patients (51 %) receiving chemotherapy for solid tumors or lymphoma developed oral and/or GI mucositis 3. Oral mucositis developed in 22% of 1236 cycles of chemotherapy, GI mucositis in 7% of cycles and both oral and GI mucositis in 8% of cycles. An even higher percentage (approximately 75–80%) of patients who receive high-dose chemotherapy prior to hematopoietic cell transplantation develop clinically significant oral mucositis 4.

Patients treated with radiation therapy for head and neck cancer typically receive an approximately 200 cGy daily dose of radiation, five days per week, for 5–7 continuous weeks. Almost all such patients will develop some degree of oral mucositis. In recent studies, severe oral mucositis occurred in 29–66% of all patients receiving radiation therapy for head and neck cancer 5, 6. The incidence of oral mucositis was especially high in 1) patients with primary tumors in the oral cavity, oropharynx or nasopharynx, 2) those who also received concomitant chemotherapy, 3) those who received a total dose over 5000 cGy, and 4) those who were treated with altered fractionation radiation schedules (e.g. more than one radiation treatment per day).

Clinical Significance of Oral Mucositis

Oral mucositis can be very painful and can significantly affect nutritional intake, mouth care, and quality of life 1, 7. For patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy prior to hematopoietic cell transplantation, oral mucositis has been reported to be the single most debilitating complication of transplantation 8. Infections associated with the oral mucositis lesions can cause life-threatening systemic sepsis during periods of profound immunosuppression 9. Moderate to severe oral mucositis has been correlated with systemic infection and transplant-related mortality 10. In patients with hematologic malignancies receiving allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, increased severity of oral mucositis was found to be significantly associated with an increased number of days requiring total parenteral nutrition and parenteral narcotic therapy, increased number of days with fever, incidence of significant infection, increased time in hospital and increased total inpatient charges 4.

In patients receiving chemotherapy for solid tumors or lymphoma, the rate of infection during cycles with mucositis was more than twice that during cycles without mucositis and was directly proportional to the severity of mucositis 3. Infection-related deaths were also more common during cycles with both oral and GI mucositis. In addition, the average duration of hospitalization was significantly longer during chemotherapy cycles with mucositis. Importantly, a reduction in the next dose of chemotherapy was twice as common after cycles with mucositis than after cycles without mucositis 3. Thus, mucositis can be a dose-limiting toxicity of cancer chemotherapy with direct effects on patient survival.

The majority of patients receiving radiation therapy for head and neck cancer are unable to continue eating by mouth due to mucositis pain and often receive nutrition through a gastrostomy tube or intravenous line. It has been demonstrated that patients with oral mucositis are significantly more likely to have severe pain and a weight loss of ≥ 5%6. In one study, approximately 16% of patients receiving radiation therapy for head and neck cancer were hospitalized due to mucositis 11. Further, 11% of the patients receiving radiation therapy for head and neck cancer had unplanned breaks in radiation therapy due to severe mucositis 11. Thus, oral mucositis is a major dose-limiting toxicity of radiation therapy to the head and neck region.

Economic Impact of Mucositis

Chemotherapy patients who have significant oral mucositis require supportive care measures such as use of total parenteral nutrition, fluid replacement and prophylaxis against infections. These can add substantially to the total cost of care. For example, in patients receiving chemotherapy for solid tumors or lymphoma, the estimated cost of hospitalization was $3893 per chemotherapy cycle without mucositis, $6277 per cycle with oral mucositis and $9132 per cycle with both oral and GI mucositis 3. A single point increase in peak mucositis scores in hematopoietic cell transplant patients is associated with one additional day of fever, a 2.1 fold increase in risk of significant infection, 2.7 additional days of total parenteral nutrition, 2.6 additional days of injectable narcotic therapy, 2.6 additional days in hospital and a 3.9 fold increase in 100-day mortality risk, collectively contributing to over $25,000 in additional hospital charges 12. Radiation-induced oral mucositis also has a significant economic impact due to costs associated with pain management, liquid diet supplements, gastrostomy tube placement or total parenteral nutrition, management of secondary infections and hospitalizations. In one study of patients receiving radiation therapy for head and neck cancer, oral mucositis was associated with an increase in costs ranging from $1700–$6000 per patient, depending on the grade of oral mucositis 6. This is fully discussed in the article, “Psychosocial and Economic Implications of Cancer.”

Pathogenesis of Mucositis

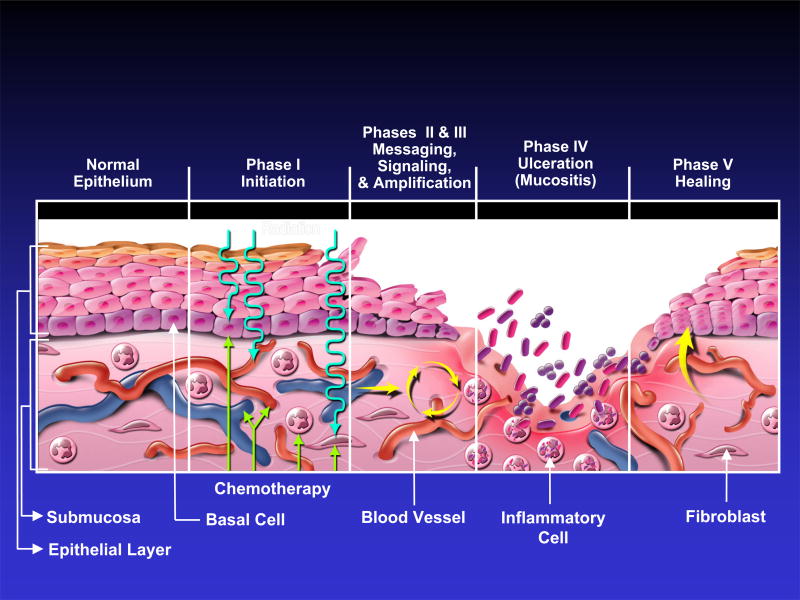

Recent studies have indicated that the fundamental mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of mucositis are much more complex than direct damage to epithelium alone 2. Mechanisms for radiation-induced and chemotherapy-induced mucositis are believed to be similar. The following five-stage model 13 for the pathogenesis of mucositis is based on the evidence available to date (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Current five-phase pathobiologic model of oral mucositis. (Reprinted from Sonis ST. A Biological Approach to Mucositis. J Support Oncol 2004; 2:21–36).

Initiation of tissue injury: Radiation and/or chemotherapy induce cellular damage resulting in death of the basal epithelial cells. The generation of reactive oxygen species (free radicals) by radiation or chemotherapy is also believed to exert a role in the initiation of mucosal injury. These small highly reactive molecules are byproducts of oxygen metabolism and can cause significant cellular damage.

Upregulation of inflammation via generation of messenger signals: In addition to causing direct cell death, free radicals activate second messengers that transmit signals from receptors on the cellular surface to the inside of the cell. This leads to upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, tissue injury and cell death.

Signaling and amplification: Upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor- alpha (TNF-α), produced mainly by macrophages, causes injury to mucosal cells, and also activates molecular pathways that amplify mucosal injury.

Ulceration and inflammation: There is a significant inflammatory cell infiltrate associated with the mucosal ulcerations, based in part on metabolic byproducts of the colonizing oral microflora. Production of pro-inflammatory cytokines is also further upregulated due to this secondary infection 14.

Healing: This phase is characterized by epithelial proliferation as well as cellular and tissue differentiation 15, restoring the integrity of the epithelium.

The degree and extent of oral mucositis that develops in any particular patient and site appears to depend on factors such as age, gender, underlying systemic disease and race as well as tissue specific factors (e.g. epithelial types, local microbial environment and function). The effects of patient age and gender on the development of oral mucositis are not clear. One study reported increased prevalence of mucositis in children 16, while other studies reported increased prevalence and/or severity in older patients 17–19. Similarly, there is conflicting evidence for the effects of gender on risk for mucositis with some studies reporting increased risk for mucositis in females 18, 20, and others finding no gender effect 19.

Interactions of such factors, coupled with underlying genetic influences, are postulated to govern the risk, course and severity of mucositis21. For example, epidermal growth factor (EGF) in luminal secretions may affect the response of intestinal mucosa to chemotherapy although over-expression of EGF in a transgenic mouse model did not reduce intestinal mucositis22. Recent studies have indicated that pathways associated with pro-inflammatory molecules including cyclo-oxygenase-2, nuclear factor-kappa B, and interleukin-6 are upregulated in oral mucositis. Thus, these may provide potential therapeutic targets for new therapies 23, 24.

Clinical Course of Oral Mucositis

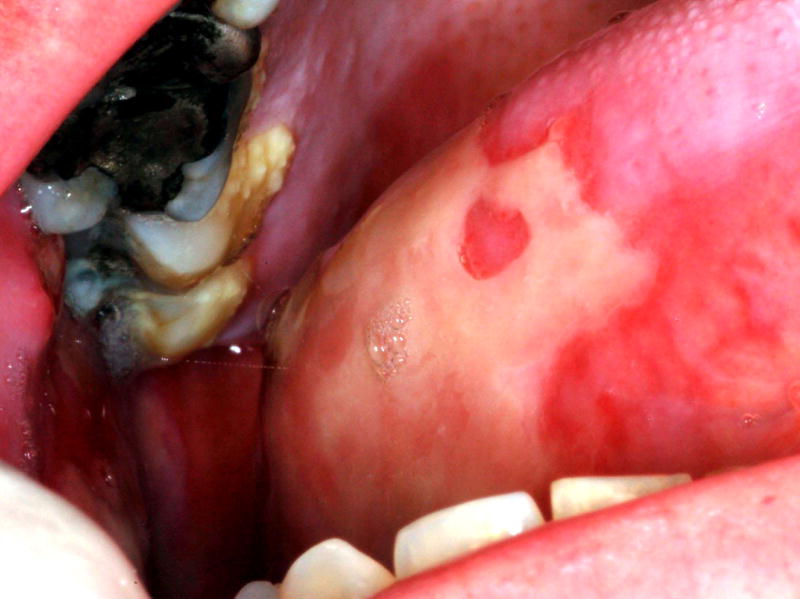

Oral mucositis initially presents as erythema of the oral mucosa which then often progresses to erosion and ulceration. The ulcerations are typically covered by a white fibrinous pseudomembrane (Figures 2 and 3). The lesions typically heal within approximately 2–4 weeks after the last dose of stomatotoxic chemotherapy or radiation therapy. In immunosuppressed patients (eg. patients undergoing hematopoetic cell transplantation), resolution of oral mucositis usually coincides with granulocyte recovery; however, this temporal relationship may or may not be causal.

Figure 2.

Oral mucositis lesion on the buccal mucosa of a patient who had received 4600 cGy of a total planned dose of 6200 cGy, without concurrent chemotherapy, for treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue.

Figure 3.

Mucositis ulcer involving the lateral tongue in the same patient as Figure 2.

Several factors affect the clinical course of mucositis. In chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis, lesions are usually limited to non-keratinized surfaces (i.e. lateral and ventral tongue, buccal mucosa and soft palate) 1. Ulcers typically arise within two weeks after initiation of chemotherapy. Selected agents such as antimetabolites and alkylating agents cause a higher incidence and severity of oral mucositis 25. In radiation-induced oral mucositis, lesions are limited to the tissues in the field of radiation, with non-keratinized tissues affected more often. The clinical severity is directly proportional to the dose of radiation administered. Most patients who have received more than 5000 cGy to the oral mucosa will develop severe ulcerative oral mucositis 26.

The clinical course of oral mucositis may sometimes be complicated by local infection, particularly in immunosuppressed patients. Viral infections such as recrudescent herpes simplex virus (HSV) and fungal infections such as candidiasis can sometimes be superimposed on oral mucositis. Although HSV infections do not cause oral mucositis 27, they can complicate its diagnosis and management.

Measurement of Oral Mucositis

A wide variety of scales have been used to record the extent and severity of oral mucositis in clinical practice and research. The World Health Organization (WHO) scale is a simple, easy to use scale that is suitable for daily use in clinical practice. This scale combines both subjective and objective measures of oral mucositis (Table 1). The National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0 includes separate subjective and objective scales for mucositis 28 (Table 2). The Oral Mucositis Assessment Scale (OMAS) is an objective scale, suitable for research purposes, that measures erythema and ulceration at nine different sites in the oral cavity. This scale has been validated in a multi-center trial with high inter-observer reproducibility and strong correlation of objective mucositis scores with patient symptoms 29. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) common toxicity criteria are also used in oncology trials to document severity of oral mucositis 30.

Table 1.

World Health Organization (WHO) scale for oral mucositis

| Grade 0 = No oral mucositis |

| Grade 1 = Erythema and Soreness |

| Grade 2 = Ulcers, able to eat solids |

| Grade 3 = Ulcers, requires liquid diet (due to mucositis) |

| Grade 4 = Ulcers, alimentation not possible (due to mucositis) |

Table 2.

National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0

| Oral mucositis (clinical exam) |

| Grade 1 = Erythema of the mucosa |

| Grade 2 = Patchy ulcerations or pseudomembranes |

| Grade 3 = Confluent ulcerations or pseudomembranes; bleeding with minor trauma |

| Grade 4 = Tissue necrosis; significant spontaneous bleeding; life-threatening consequences |

| Grade 5 = Death |

| Oral mucositis (functional/symptomatic) |

| Grade 1 = Minimal symptoms, normal diet |

| Grade 2 = Symptomatic but can eat and swallow modified diet |

| Grade 3 = Symptomatic and unable to adequately aliment or hydrate orally |

| Grade 4 = Symptoms associated with life-threatening consequences |

| Grade 5 = Death |

Clinical Management of Oral Mucositis

Management of oral mucositis has been largely palliative to date, although targeted therapeutic interventions are now being developed 31. Based on a comprehensive systematic review of the literature, the Mucositis Study Group of the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer and the International Society of Oral Oncology (MASCC/ISOO) has developed clinical practice guidelines for the management of mucositis 32. These guidelines are referenced below as applicable. Management of oral mucositis is divided into the following sections: nutritional support, pain control, oral decontamination, palliation of dry mouth, management of oral bleeding and therapeutic interventions for oral mucositis.

Pain control

The primary symptom of oral mucositis is pain. This pain significantly affects nutritional intake, mouth care and quality of life. Thus, management of mucositis pain is a primary component of any mucositis management strategy. Many centers use saline mouth rinses, ice chips and topical mouthrinses containing an anesthetic such as 2% viscous lidocaine. The lidocaine may be mixed with equal volumes of diphenhydramine and a soothing covering agent such as Maalox (Novartis Consumer Health, Inc., Fremont, MI) or Kaopectate (Chattem, Inc., Chattanooga, TN) in equal volumes. Such topical anesthetic agents may provide short-term relief.

A number of other topical mucosal bioadherent agents are also available that are not anesthetics but are postulated to reduce pain by forming a protective coating over ulcerated mucosa. Of these, sucralfate is the most widely studied. The MASCC/ISOO guidelines recommend against the use of sucralfate in radiation-induced oral mucositis due to lack of efficacy. No recommendation has been made for the use of sucralfate in chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis due to lack of consistent results 33–35. In addition to the use of topical agents, most patients with severe mucositis require systemic analgesics, often including opioids, for satisfactory pain relief. The MASCC/ISOO guidelines recommend patient-controlled analgesia with morphine for patients undergoing hematopoetic cell transplantation 35.

Nutritional Support

Nutritional intake can be severely compromised by the pain associated with severe oral mucositis. In addition, taste changes can also occur secondary to chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy 36; 37. It is essential that nutritional intake and weight be monitored by a dietician or other professional working together with family caregivers. A soft diet and liquid diet supplements are more easily tolerated than a normal diet when oral mucositis is present. In patients expected to develop severe mucositis, a gastrostomy tube is sometimes placed prophylactically although this varies considerably from center to center. In patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation, total parenteral nutrition is usually given via an indwelling catheter such as a Hickman line.

Oral Decontamination

Oral decontamination may result in significant positive outcomes in this population. Firstly, it has been hypothesized that microbial colonization of oral mucositis lesions exacerbates the severity of oral mucositis and therefore, decontamination may help to reduce mucositis. Indeed, multiple studies have demonstrated that maintenance of good oral hygiene can reduce the severity of oral mucositis 38–40. Patients who have undergone hematopoietic cell transplantation and who develop oral mucositis also have been found to be three times more likely to develop bacteremias resulting in increased length of hospital stays as compared to patients without mucositis 10. Therefore, oral decontamination may reduce mucositis that in turn, may reduce bacteremia. Furthermore, oral decontamination can reduce infection of the oral cavity by opportunistic pathogens 41. Therefore, a second function of oral decontamination can be to reduce the risk of systemic sepsis from resident oral and/or opportunistic pathogens. This is especially true in patients who are immunosuppressed due to chemotherapy. The risk of systemic sepsis from oral mucositis has not been well studied although one study found that an intensive oral care protocol decreased risk of oral mucositis but not the percentage of patients with a documented septicemia 40. Patients receiving radiation therapy alone are less likely to develop sepsis of oral origin.

The MASCC/ISOO guidelines recommend use of a standardized oral care protocol including brushing with a soft toothbrush, flossing and the use of non-medicated rinses (e.g. saline or sodium bicarbonate rinses). Patients and caregivers should be educated regarding the importance of effective oral hygiene 42. Alcohol-containing chlorhexidine mouthrinse may be difficult for patients to tolerate during clinical oral ulceration, thus formulations without alcohol are used at some centers. Multiple studies have examined the role of chlorhexidine mouthrinse in oral mucositis but have not demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing severity of mucositis35,. Therefore, the MASCC/ISOO guidelines recommend against the use of chlorhexidine mouthrinse for prevention or treatment of oral mucositis.

Nystatin rinse has not been found to be effective in reducing the severity of chemotherapy-induced mucositis 43. On the other hand, a recent study indicated that systemic fluconazole vs. no treatment significantly and dramatically reduced both candidal carriage and incidence of severe mucositis induced by radiation therapy (15% vs. 45%) in patients with head and neck cancer. 44. The MASCC/ISOO guidelines recommend against the routine use of antimicrobial lozenges or of acyclovir and its analogues to prevent oral mucositis 35. However, drugs such as acyclovir and valacycovir have a well-established role in prophylaxis and treatment of lesions caused by HSV in this patient population 45, 46 (see the article, “Management of Oral Infections in the Patient with Cancer”).

Palliation of dry mouth

Patients undergoing cancer therapy often develop transient or permanent xerostomia (subjective symptom of dryness) and hyposalivation (objective reduction in salivary flow). Hyposalivation can further aggravate inflamed tissues, increase risk for local infection and make mastication difficult. Many patients also complain of a thickening of salivary secretions due a decrease in the serous component of saliva. The following measures can be taken for palliation of a dry mouth:

Sip water as needed to alleviate mouth dryness. Several supportive products including artificial saliva are available.

Rinse with a solution of 1/2 tsp baking soda (and/or ¼ or ½ teaspoon of table salt) in 1 cup warm water several times a day to clean and lubricate the oral tissues and to buffer the oral environment

Chew sugarless gum to stimulate salivary flow.

Use cholinergic agents as necessary

Please also see the article by Fischer and Epstein, “Management of Patients Who Have Undergone Head and Neck Cancer Therapy,” for more details.

Management of bleeding

In patients who are thrombocytopenic due to high-dose chemotherapy (eg hematopoietic cell transplant recipients), bleeding may occur from the ulcerations of oral mucositis. Local intraoral bleeding can usually be controlled with the use of topical hemostatic agents such as fibrin glue or gelatin sponge 47. Patients whose platelet counts fall below 20,000 require platelet transfusion due to risk for spontaneous internal bleeding which may have grave consequences especially in the central nervous system.

Therapeutic Interventions

Several agents have been tested to reduce the severity of, or prevent mucositis. These different classes of agents are discussed briefly below in the context of the MASCC/ISOO guidelines where applicable.

Cryotherapy

It has been hypothesized that topical administration of ice chips to the oral cavity during administration of chemotherapy results in decreased delivery of the chemotherapeutic agent to the oral mucosa. This effect is presumably mediated through local vasoconstriction and reduced blood flow. Several studies have demonstrated that cryotherapy reduces the severity of oral mucositis in patients receiving bolus doses of chemotherapeutic agents 48–50. The MASCC/ISOO guidelines recommend the use of cryotherapy to reduce oral mucositis in patients receiving bolus doses of 5-fluorouracil, melphalan and edatrexate 51. Ice chips are placed in the mouth, beginning 5 minutes before administration of chemotherapy and replenished as needed for up to 30 minutes. Cryotherapy is only useful for short bolus chemotherapeutic infusions, may not be well tolerated in some subjects and does not have a role in radition-induced oral mucositis.

Growth Factors

Reduction in the proliferative capacity of oral epithelial cells is thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of mucositis. Therefore, various growth factors that can increase epithelial cell proliferation have been studied for the management of oral mucositis. Recent evidence shows that IV recombinant human keratinocyte growth factor-1 (Palifermin, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) significantly reduced incidence of WHO grade 3 and 4 oral mucositis in patients with hematologic malignancies (e.g. lymphoma and multiple myeloma) receiving high-dose chemotherapy and total body irradiation before autologous hematopoetic cell transplantation 52. Based on this, the MASCC/ISOO guidelines recommend the use of this growth factor in this specific population53. Palifermin has also been approved by the United States (U.S.) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients with hematologic malignancies receiving myelotoxic therapies requiring hematopoietic cell support. Interestingly, a related compound, human keratinocyte growth factor-2 (Repifermin, Human Genome Sciences, Rockville, MD), was found to be ineffective in reducing the percentage of subjects who experienced severe mucositis 54. Intravenous human fibroblast growth factor-20 (Velafermin, Curagen Corp., Branford, CT) is currently in clinical development for reduction of mucositis secondary to high dose chemotherapy in autologous hematopoetic cell transplant patients 55.

The safety of this class of growth factors has not been established in patients with nonhematologic malignancies. There is a theoretical concern that these growth factors may promote growth of tumor cells, which may have receptors for the respective growth factor. However, one recent study found no significant difference in survival between subjects with colorectal cancer receiving palifermin or placebo at a median follow-up duration of 14.5 months 56. Further studies are ongoing to confirm the safety of epithelial growth factors in the solid tumor setting including patients receiving radiation therapy for head and neck cancer.

Anti-inflammatory agents

Benzydamine hydrochloride is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug that inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α. In one Phase III trial, benzydamine hydrochloride mouthrinse reduced the severity of mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiation therapy of cumulative doses up to 50 Gy radiation therapy 57. Based on this and previous studies, the MASCC/ISOO guidelines recommended use of this agent in patients receiving moderate-dose radiation therapy 58. However, this agent has not received approval for this use from the U.S. FDA; furthermore, most patients with head and neck cancer receive well over 50 Gy radiation therapy with concomitant chemotherapy. A more recent Phase III trial of this agent in radiation-induced oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer was halted based on negative results of an interim analysis.

Saforis (MGI Pharma) is a proprietary oral suspension of L-glutamine that enhances the uptake of this amino acid into epithelial cells. Glutamine may reduce mucosal injury by reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines and cytokine-related apoptosis 59, 60 and may promote healing by increasing fibroblast and collagen synthesis 61. In a Phase III study, this topical agent reduced the incidence of clinically significant chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis as compared to placebo 62. By comparison, the MASCC/ISOO guidelines recommend that systemically administered glutamine not be used for the prevention of GI mucositis 35, because of lack of efficacy 63.

Antioxidants

Amifostine (Ethylol, MedImmune, Gaithersburg, MD) is thought to act as a scavenger for harmful reactive oxygen species which are known to potentiate mucositis 64. However, due to insufficient evidence of benefit, a MASCC/ISOO guideline could not be established regarding the use of this agent in oral mucositis in chemotherapy or radiation therapy patients. The use of amifostine was recommended for the prevention of esophagitis in patients receiving chemo-radiation for non-small-cell lung cancer 65. RK-0202 (RxKinetix) consists of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine in a proprietary matrix for topical application in the oral cavity. In a placebo-controlled phase II trial in patients with head and neck cancer, this agent significantly reduced the incidence of severe oral mucositis up to doses of 50 Gy radiation therapy 66.

Low-Level Laser Therapy

Multiple studies have indicated that low-level laser therapy can reduce the severity of chemotherapy and radiation-induced oral mucositis 67–69, although the mechanism of such an effect is not understood. It has been speculated that low-level laser therapy may reduce levels of reactive oxygen species and/or pro-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to the pathogenesis of mucositis. Studies are difficult to compare due to varying laser types and parameters (such as wavelength). Nevertheless, based on the encouraging results to date, the MASCC/ISOO guidelines suggest the use of low-level laser therapy in chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis at centers able to support the necessary technology and training 51.

Future Directions in Mucositis Research

As evident from the above discussion, this is an exciting period in mucositis research. One drug (Palifermin) has received FDA approval for reducing the severity and duration of oral mucositis in patients with hematologic malignancies receiving myelotoxic therapies requiring hematopoietic cell support. Several other promising agents are in clinical development that eventually may be approved for the management of this debilitating condition. Future studies should evaluate if agents that work by different mechanisms can be used in combination for greater clinical effectiveness. Another approach that warrants further investigation is the use of novel drug delivery technologies that increase uptake of the active agent (e.g. glutamine) to the oral epithelial cells. In addition, developing improved algorithms to predict the risk for the development of clinically significant mucositis would also be valuable so that patients at increased risk can be targeted for therapy in a more cost-effective manner. Reducing the morbidity of mucositis will help to avoid unwanted dose reductions or unscheduled breaks in cancer therapy and thus improve outcomes of cancer therapy.

Summary

Oral mucositis is a clinically important and sometimes dose-limiting complication of cancer therapy. Mucositis lesions can be painful, affect nutrition and quality of life, and have a significant economic impact. The pathogenesis of oral mucositis is multifactorial and complex. The present review discusses the morbidity, economic impact, pathogenesis and clinical course of mucositis. Current clinical management of oral mucositis is largely focused on palliative measures such as pain management, nutritional support and maintenance of good oral hygiene. However, several promising therapeutic agents are in various stages of clinical development for the management of oral mucositis. These agents are discussed in the context of recently updated evidence-based clinical management guidelines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant Number K23DE016946 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Lalla has served as a paid consultant for MGI Pharma.

Dr. Sonis has received research support from Amgen, Medimmune, and Novartis. He is a consultant to Biomodels LLC and Clinical Assistance Programs LLC.

Dr. Peterson has served as paid consultant for MGI Pharma and Nuvelo.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lalla RV, Peterson DE. Oral mucositis. Dent Clin North Am. 2005 Jan;49(1):167–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treister N, Sonis S. Mucositis: biology and management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007 Apr;15(2):123–129. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3280523ad6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elting LS, Cooksley C, Chambers M, Cantor SB, Manzullo E, Rubenstein EB. The burdens of cancer therapy. Clinical and economic outcomes of chemotherapy-induced mucositis. Cancer. 2003 Oct 1;98(7):1531–1539. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vera-Llonch M, Oster G, Ford CM, Lu J, Sonis S. Oral mucositis and outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in patients with hematologic malignancies. Support Care Cancer. 2007 May;15(5):491–496. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vera-Llonch M, Oster G, Hagiwara M, Sonis S. Oral mucositis in patients undergoing radiation treatment for head and neck carcinoma. Cancer. 2006 Jan 15;106(2):329–336. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elting LS, Cooksley CD, Chambers MS, Garden AS. Risk, outcomes, and costs of radiation-induced oral mucositis among patients with head-and-neck malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007 Mar 28; doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncan GG, Epstein JB, Tu D, et al. Quality of life, mucositis, and xerostomia from radiotherapy for head and neck cancers: a report from the NCIC CTG HN2 randomized trial of an antimicrobial lozenge to prevent mucositis. Head Neck. 2005 May;27(5):421–428. doi: 10.1002/hed.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellm LA, Epstein JB, Rose-Ped A, Martin P, Fuchs HJ. Patient reports of complications of bone marrow transplantation. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8(1):33–39. doi: 10.1007/s005209900095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rapoport AP, Miller Watelet LF, Linder T, et al. Analysis of factors that correlate with mucositis in recipients of autologous and allogeneic stem-cell transplants. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2446–2453. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruescher TJ, Sodeifi A, Scrivani SJ, Kaban LB, Sonis ST. The impact of mucositis on alpha-hemolytic streptococcal infection in patients undergoing autologous bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Cancer. 1998;82(11):2275–2281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trotti A, Bellm LA, Epstein JB, et al. Mucositis incidence, severity and associated outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy: a systematic literature review. Radiother Oncol. 2003 Mar;66(3):253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sonis ST, Oster G, Fuchs H, et al. Oral mucositis and the clinical and economic outcomes of hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(8):2201–2205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonis ST, Elting LS, Keefe D, et al. Perspectives on Cancer Therapy-Induced Mucosal Injury: Pathogenesis, Measurement, Epidemiology, and Consequences for Patients. Cancer. 2004;100(S9):1995–2025. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonis ST, Peterson RL, Edwards LJ, et al. Defining mechanisms of action of interleukin-11 on the progression of radiation-induced oral mucositis in hamsters. Oral Oncol. 2000;36(4):373–381. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorr W, Emmendorfer H, Haide E, Kummermehr J. Proliferation equivalent of ‘accelerated repopulation’ in mouse oral mucosa. Int J Radiat Biol. 1994;66(2):157–167. doi: 10.1080/09553009414551061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonis ST, Sonis AL, Lieberman A. Oral complications in patients receiving treatment for malignancies other than of the head and neck. J Am Dent Assoc. 1978 Sep;97(3):468–472. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1978.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarthy GM, Awde JD, Ghandi H, Vincent M, Kocha WI. Risk factors associated with mucositis in cancer patients receiving 5-fluorouracil. Oral Oncol. 1998 Nov;34(6):484–490. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zalcberg J, Kerr D, Seymour L, Palmer M. Haematological and nonhaematological toxicity after 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with advanced colorectal cancer is significantly associated with gender, increasing age and cycle number. Tomudex International Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1998 Nov;34(12):1871–1875. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rocke LK, Loprinzi CL, Lee JK, et al. A randomized clinical trial of two different durations of oral cryotherapy for prevention of 5-fluorouracil-related stomatitis. Cancer. 1993 Oct 1;72(7):2234–2238. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931001)72:7<2234::aid-cncr2820720728>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vokurka S, Bystricka E, Koza V, et al. Higher incidence of chemotherapy induced oral mucositis in females: a supplement of multivariate analysis to a randomized multicentre study. Support Care Cancer. 2006 Sep;14(9):974–976. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0031-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anthony L, Bowen J, Garden A, Hewson I, Sonis S. New thoughts on the pathobiology of regimen-related mucosal injury. Support Care Cancer. 2006 Jun;14(6):516–518. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang FS, Kemp CJ, Williams JL, Erwin CR, Warner BW. Role of epidermal growth factor and its receptor in chemotherapy-induced intestinal injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002 Mar;282(3):G432–442. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00166.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonis S, Haddad R, Posner M, et al. Gene expression changes in peripheral blood cells provide insight into the biological mechanisms associated with regimen-related toxicities in patients being treated for head and neck cancers. Oral Oncol. 2007 Mar;43(3):289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Logan RM, Gibson RJ, Sonis ST, Keefe DM. Nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression in the oral mucosa following cancer chemotherapy. Oral Oncol. 2007 Apr;43(4):395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barasch A, Peterson DE. Risk factors for ulcerative oral mucositis in cancer patients: unanswered questions. Oral Oncol. 2003 Feb;39(2):91–100. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(02)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epstein JB, Gorsky M, Guglietta A, Le N, Sonis ST. The correlation between epidermal growth factor levels in saliva and the severity of oral mucositis during oropharyngeal radiation therapy. Cancer. 2000;89(11):2258–2265. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11<2258::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woo SB, Sonis ST, Sonis AL. The role of herpes simplex virus in the development of oral mucositis in bone marrow transplant recipients. Cancer. 1990 Dec 1;66(11):2375–2379. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901201)66:11<2375::aid-cncr2820661121>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v30 (CTCAE) [Accessed 10 May, 2007];Internet document. Available at: http://ctep.info.nih.gov/reporting/ctc_v30.html.

- 29.Sonis ST, Eilers JP, Epstein JB, et al. Validation of a new scoring system for the assessment of clinical trial research of oral mucositis induced by radiation or chemotherapy. Mucositis Study Group. Cancer. 1999;85(10):2103–2113. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990515)85:10<2103::aid-cncr2>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Group ECO. ECOG Common Toxicity Criteria. [Accessed 30 August, 2007];Internet Document]

- 31.Lalla RV, Peterson DE. Treatment of mucositis, including new medications. Cancer J. 2006 Sep-Oct;12(5):348–354. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keefe DM, Schubert MM, Elting LS, et al. Updated clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of mucositis. Cancer. 2007 Mar 1;109(5):820–831. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dodd MJ, Miaskowski C, Greenspan D, et al. Radiation-induced mucositis: a randomized clinical trial of micronized sucralfate versus salt & soda mouthwashes. Cancer Invest. 2003;21(1):21–33. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120016400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nottage M, McLachlan SA, Brittain MA, et al. Sucralfate mouthwash for prevention and treatment of 5-fluorouracil-induced mucositis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2003 Jan;11(1):41–47. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barasch A, Elad S, Altman A, Damato K, Epstein J. Antimicrobials, mucosal coating agents, anesthetics, analgesics, and nutritional supplements for alimentary tract mucositis. Support Care Cancer. 2006 Jun;14(6):528–532. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng KK. Oral mucositis, dysfunction, and distress in patients undergoing cancer therapy. J Clin Nurs. 2007 Feb 20; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raber-Durlacher J, Barasch A, Peterson DE, Lalla RV, Schubert MM, Fibbe WE. Oral Complications and Management Considerations in Patients Treated with High-Dose Cancer Chemotherapy. Supportive Cancer Therapy. 2004;1(4):219–229. doi: 10.3816/SCT.2004.n.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng KK, Molassiotis A, Chang AM, Wai WC, Cheung SS. Evaluation of an oral care protocol intervention in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis in paediatric cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2001 Nov;37(16):2056–2063. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levy-Polack MP, Sebelli P, Polack NL. Incidence of oral complications and application of a preventive protocol in children with acute leukemia. Spec Care Dentist. 1998 Sep-Oct;18(5):189–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1998.tb01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borowski B, Benhamou E, Pico JL, Laplanche A, Margainaud JP, Hayat M. Prevention of oral mucositis in patients treated with high-dose chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation: a randomised controlled trial comparing two protocols of dental care. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1994;30B(2):93–97. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoneda S, Imai S, Hanada N, et al. Effects of oral care on development of oral mucositis and microorganisms in patients with esophageal cancer. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2007 Feb;60(1):23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGuire DB, Correa ME, Johnson J, Wienandts P. The role of basic oral care and good clinical practice principles in the management of oral mucositis. Support Care Cancer. 2006 Jun;14(6):541–547. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Epstein JB, Vickars L, Spinelli J, Reece D. Efficacy of chlorhexidine and nystatin rinses in prevention of oral complications in leukemia and bone marrow transplantation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73(6):682–689. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90009-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicolatou-Galitis O, Velegraki A, Sotiropoulou-Lontou A, et al. Effect of fluconazole antifungal prophylaxis on oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients receiving radiotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2006 Jan;14(1):44–51. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saral R, Ambinder RF, Burns WH, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis against herpes simplex virus infection in patients with leukemia. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1983 Dec;99(6):773–776. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-6-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saral R, Burns WH, Laskin OL, Santos GW, Lietman PS. Acyclovir prophylaxis of herpes-simplex-virus infections. N Engl J Med. 1981 Jul 9;305(2):63–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198107093050202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aframian DJ, Lalla RV, Peterson DE. Management of dental patients taking common hemostasis-altering medications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007 Mar;103(Suppl):S45 e41–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cascinu S, Fedeli A, Fedeli SL, Catalano G. Oral cooling (cryotherapy), an effective treatment for the prevention of 5-fluorouracil-induced stomatitis. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1994 Jul;30B(4):234–236. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aisa Y, Mori T, Kudo M, et al. Oral cryotherapy for the prevention of high-dose melphalan-induced stomatitis in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Support Care Cancer. 2005 Apr;13(4):266–269. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0726-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahood DJ, Dose AM, Loprinzi CL, et al. Inhibition of fluorouracil-induced stomatitis by oral cryotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1991 Mar;9(3):449–452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Migliorati CA, Oberle-Edwards L, Schubert M. The role of alternative and natural agents, cryotherapy, and/or laser for management of alimentary mucositis. Support Care Cancer. 2006 Jun;14(6):533–540. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spielberger R, Stiff P, Bensinger W, et al. Palifermin for oral mucositis after intensive therapy for hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 16;351(25):2590–2598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.von Bultzingslowen I, Brennan MT, Spijkervet FK, et al. Growth factors and cytokines in the prevention and treatment of oral and gastrointestinal mucositis. Support Care Cancer. 2006 Jun;14(6):519–527. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Human Genome Sciences reports results of phase 2 clinical trial of Repifermin in patients with cancer therapy-induced mucositis. Rockville, MD: Human Genome Sciences; 2 February, 2004. (Press Release) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lalla RV. Velafermin (CuraGen) Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005 Nov;6(11):1179–1185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosen LS, Abdi E, Davis ID, et al. Palifermin reduces the incidence of oral mucositis in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Nov 20;24(33):5194–5200. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Epstein JB, Silverman S, Jr, Paggiarino DA, et al. Benzydamine HCl for prophylaxis of radiation-induced oral mucositis: results from a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled clinical trial. Cancer. 2001;92(4):875–885. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4<875::aid-cncr1396>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lalla RV, Schubert MM, Bensadoun RJ, Keefe D. Anti-inflammatory agents in the management of alimentary mucositis. Support Care Cancer. 2006 Jun;14(6):558–565. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coeffier M, Marion R, Leplingard A, Lerebours E, Ducrotte P, Dechelotte P. Glutamine decreases interleukin-8 and interleukin-6 but not nitric oxide and prostaglandins e(2) production by human gut in-vitro. Cytokine. 2002 Apr 21;18(2):92–97. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Evans ME, Jones DP, Ziegler TR. Glutamine prevents cytokine-induced apoptosis in human colonic epithelial cells. J Nutr. 2003 Oct;133(10):3065–3071. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.10.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bellon G, Monboisse JC, Randoux A, Borel JP. Effects of preformed proline and proline amino acid precursors (including glutamine) on collagen synthesis in human fibroblast cultures. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987 Aug 19;930(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(87)90153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peterson DE, Jones JB, Petit RG., 2nd Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of Saforis for prevention and treatment of oral mucositis in breast cancer patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15;109(2):322–331. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pytlik R, Benes P, Patorkova M, et al. Standardized parenteral alanyl-glutamine dipeptide supplementation is not beneficial in autologous transplant patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002 Dec;30(12):953–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mantovani G, Maccio A, Madeddu C, et al. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidant mechanisms, and serum cytokine levels in cancer patients: impact of an antioxidant treatment. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2003;22(1):17–28. doi: 10.1615/jenvpathtoxoncol.v22.i1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bensadoun RJ, Schubert MM, Lalla RV, Keefe D. Amifostine in the management of radiation-induced and chemo-induced mucositis. Support Care Cancer. 2006 Jun;14(6):566–572. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.RxKinetix completes its end of phase 2 meeting with the FDA for RK-0202 in oral mucositis and is now moving into phase 3. Boulder, CO: RxKinetix, Inc.; 1 March, 2006. (Press Release) [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barasch A, Peterson DE, Tanzer JM, et al. Helium-neon laser effects on conditioning-induced oral mucositis in bone marrow transplantation patients. Cancer. 1995 Dec 15;76(12):2550–2556. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951215)76:12<2550::aid-cncr2820761222>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bensadoun RJ, Franquin JC, Ciais G, et al. Low-energy He/Ne laser in the prevention of radiation-induced mucositis. A multicenter phase III randomized study in patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer. 1999 Jul;7(4):244–252. doi: 10.1007/s005200050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schubert MM, Eduardo FP, Guthrie KA, et al. A phase III randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial to determine the efficacy of low level laser therapy for the prevention of oral mucositis in patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Support Care Cancer. 2007 Mar 29; doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]