Abstract

Worldwide, several regions suffer from water scarcity and contamination. The infiltration and subsurface storage of rain and river water can reduce water stress. Artificial groundwater recharge, possibly combined with bank filtration, plant purification and/or the use of subsurface dams and artificial aquifers, is especially advantageous in areas where layers of gravel and sand exist below the earth’s surface. Artificial infiltration of surface water into the uppermost aquifer has qualitative and quantitative advantages. The contamination of infiltrated river water will be reduced by natural attenuation. Clay minerals, iron hydroxide and humic matter as well as microorganisms located in the subsurface have high decontamination capacities. By this, a final water treatment, if necessary, becomes much easier and cheaper. The quantitative effect concerns the seasonally changing river discharge that influences the possibility of water extraction for drinking water purposes. Such changes can be equalised by seasonally adapted infiltration/extraction of water in/out of the aquifer according to the river discharge and the water need. This method enables a continuous water supply over the whole year. Generally, artificially recharged groundwater is better protected against pollution than surface water, and the delimitation of water protection zones makes it even more save.

Keywords: Artificial groundwater recharge, Natural attenuation, Water management

INTRODUCTION

The growing population and an increase of industrialisation and agricultural production in numerous countries require more and more water of adequate quality. In many regions there is a lack of surface water and severe water contamination is to be found. Shallow groundwater resources are often of insufficient quality and over-exploited. Therefore, it is of high priority to take into consideration all the proved water techniques that could help to reduce the existing disaster.

Artificial groundwater recharge is an approved method that has been improved during the last decades. It has been found that also the new kinds of polluting agents, especially organic compounds, can be minimized or even removed by natural purification processes in the subsurface.

ARTIFICIAL GROUNDWATER RECHARGE

Artificial groundwater recharge is the infiltration of surface water into shallow aquifers to increase the quantity of water stored in the subsurface and to improve its quality by processes of natural attenuation (Balke et al., 2000). It can be practiced especially in river valleys and sedimentary plains by infiltrating river or lake water into shallow sand and gravel layers. The infiltration technique is chosen according to the hydrogeological conditions, the available ground space, the water need, the composition of the infiltrated water, and the degree of purification to be achieved (Schmidt, 1980; Schmidt and Balke, 1980; 1985). In order to improve the efficiency of natural purification processes in the subsurface, artificial groundwater recharge can be combined with pre-treatment, bank filtration, plant purification, subsurface dams and artificial aquifers (Balke et al., 2000; Preuß and Schulte-Ebbert, 2000).

Natural purification processes

Surface water contains inorganic and organic compounds of natural origin as suspended matter and dissolved substances. In most cases, water in river and lake is contaminated by waste, sewage, chemicals, hydrocarbons, medicine, hormones, antibiotics, bacteria, viruses, fertilizers, plant-protective agents, etc. and their decay products (Balke, 1990; 2003; Balke and Zhu, 2003; Remmler and Schulte-Ebbert, 2003). For drinking purposes, the contaminations in water must be removed or destroyed by purifying processes as completely as possible.

Natural purification effects within filter layers and in the subsurface are caused mainly by filtration, sedimentation, precipitation, oxidation-reduction, sorption-desorption, ion-exchange and biodegradation.

In plants for artificial groundwater recharge, the water being infiltrated at first passes an artificially installed layer of filter sand. This filter layer retains coarser particles by filtration.

Chemical reactions between infiltrated water, solid inorganic and organic substances in the subsurface, and the groundwater flowing towards the extraction well may cause precipitation of sparingly soluble carbonates, hydroxides and sulphides—governed by pH-value and redox-potential—within the filter layer and the aquifer.

The oxygen content of the water is decisive for oxidation processes and activities of microorganisms. The presence of reducing substances such as humic matter, causing a lack of oxygen, is responsible for chemical reductions. pH-value and redox-potential influence these reactions, too.

Dissolved compounds, among them also contaminants, can be adsorbed especially by clay minerals, iron-hydroxides, amorphous silicic acid, and organic substances. If the chemical composition of the water changes, desorption may happen.

Ion exchange processes take place mainly in the presence of organic matter and clay minerals. One kind of ion is exchanged against another in stoichiometric relation, e.g.,

. .

|

In this way, contaminating ions can also be fixed at underground.

The forming of ionic and molecular complexes changes the solubility, precipitation and sorption of substances such as heavy metals and organic compounds.

Within the layer of filter sand and the aquifer, a great variety of natural microorganisms exist, which are highly involved in rehabilitation processes (Balke and Griebler, 2003). Biodegradation, the decay of organic compounds by microorganisms, reduces the amount of organics, no matter they are of natural origin or stemming from contaminations.

The community of purifying organisms mainly consists of autochthonous bacteria, protozoa and metazoa. The group of protozoa includes flagellates, ciliates, amoebas, etc., and the group of metazoa includes worms, nematodes, annelids and arthropods. The density of this population of organisms decreases, as well as the removal efficiency (Fig.1).

Fig. 1.

Purification process during vertical infiltration of water (Preuß and Schulte-Ebbert, 2000)

Allochthonous microorganisms, especially pathogenous bacteria such as Salmonellae, Legionellae, Streptococcus, Vibrio cholerae, Escherichia coli, and endangering viruses such as hepatitis-A and -B, poliomyelitis, etc. that have been introduced into the subsurface by the seepage of contaminated water or sewage, are normally eliminated after a certain period of time.

In order to reduce the danger of groundwater contamination from the landside, the groundwater recharge area of waterwork wells has to be protected by groundwater protection zones.

Techniques of artificial groundwater recharge

Water can be infiltrated into aquifers with the help of basins, pipes, ditches and wells (Balke, 2004).

Infiltration basins (Fig.2) positioned above an aquifer with sufficient hydraulic permeability often have sizes ranging from 100 to 10 000 m2. The thickness of the uppermost layer of filter sand ranges from 50 to 100 cm, and the grain size should be less than 3 mm. The water to be infiltrated passes over a cascade in order to enrich its oxygen content. Then it percolates the sand filter and the unsaturated zone and finally reaches the groundwater table. The slopes of infiltration basins can be stabilized with concrete parts or designed in a natural mode.

Fig. 2.

Cross section of an infiltration basin with cascade (ORL-ETHZ, 1970)

The quantitative efficiency of the filter sand layer is influenced by the permeability of the filter sand, the mode of rain fall, the growing up of algae, etc. The rate of filtration drops in the course of time, and after a certain period the filter layer must be cleaned or replaced.

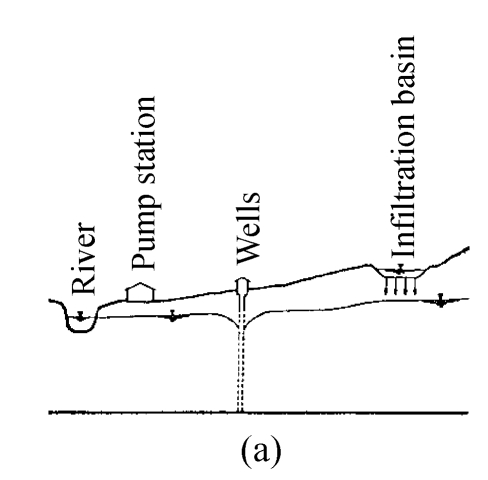

A plant for artificial groundwater recharge consists of a source of surface water, a pump station, an infiltration basin and extraction wells (Fig.3).

Fig. 3.

Scheme of artificial groundwater recharge by infiltration basins. (a) Profile; (b) Map (ORL-ETHZ, 1970)

Besides the purification effects, artificial groundwater recharge also enables a better water management (Zhu and Balke, 2005). During periods with mean river water discharge and mean groundwater levels (Curve a in Fig.4), as much water can be infiltrated and naturally purified as needed by the consumers. With regard to later periods with low river water discharge, a surplus of water can be infiltrated into the aquifer. This operation during periods with mean and high river water discharges increases the amount of stored water that is documented by a rising groundwater level (Curve b in Fig.4).

Fig. 4.

Management of water storage and availability, the lines represent the river water and the appertaining groundwater levels

During periods with low river water discharge and a reduced possibility to infiltrate river water, the water stored underground by former infiltration and even a surplus can be pumped out. By this, the groundwater level can be lowered from Phase b to Phase c (Curve c in Fig.4), according to the thickness of the aquifer and the depth of the well. In this way it is possible to manage the water supply. Besides, in the case of extreme river water contamination by chemical accidents or ship collisions, the withdrawal from the river can be stopped temporarily until the highly contaminated water passed away.

For the infiltration of smaller quantities of water, infiltration pipes, surrounded by filter sand and located 1 to 3 m below the earth’s surface, can be used (Fig.5a); for bigger quantities of water, infiltration galleries are recommended (Fig.5b).

Fig. 5.

Scheme of an infiltration pipe (ORL-ETHZ, 1970). (a) Infiltration pipes; (b) Infiltration galleries

In many cases, infiltration ditches, filled with filter sand, are applied with lengths between 10 and 100 m, width of ca. 1 m, and depths of 4 to 6 m (Fig.6).

Fig. 6.

Scheme of an infiltration ditch (Wolters and Hantke, 1982)

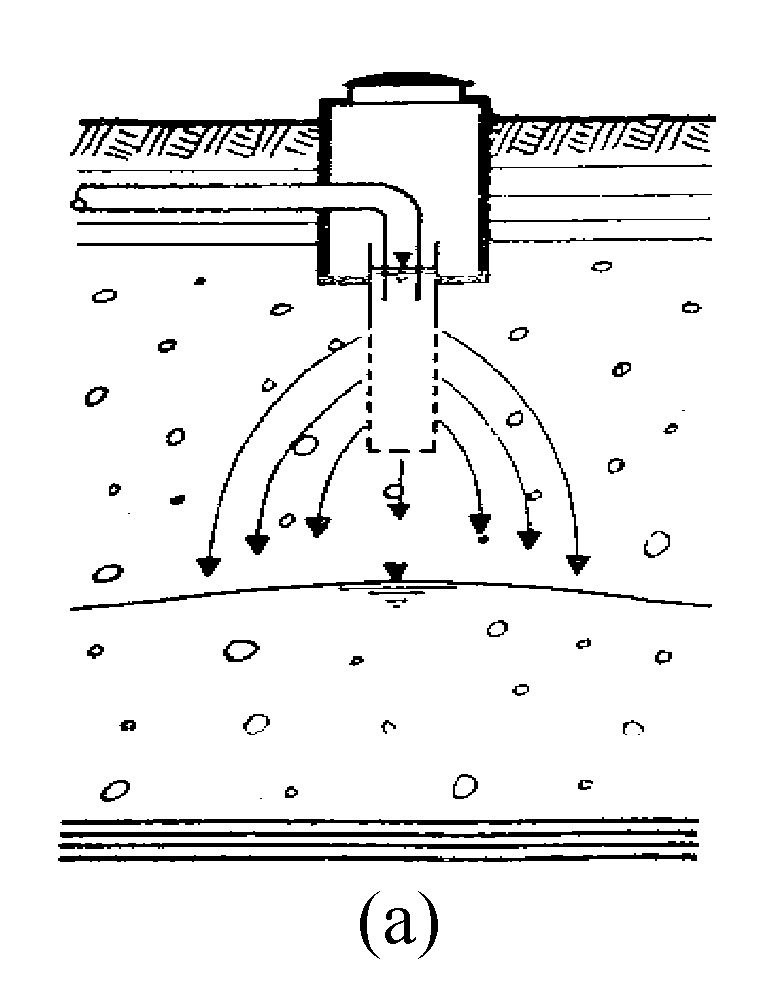

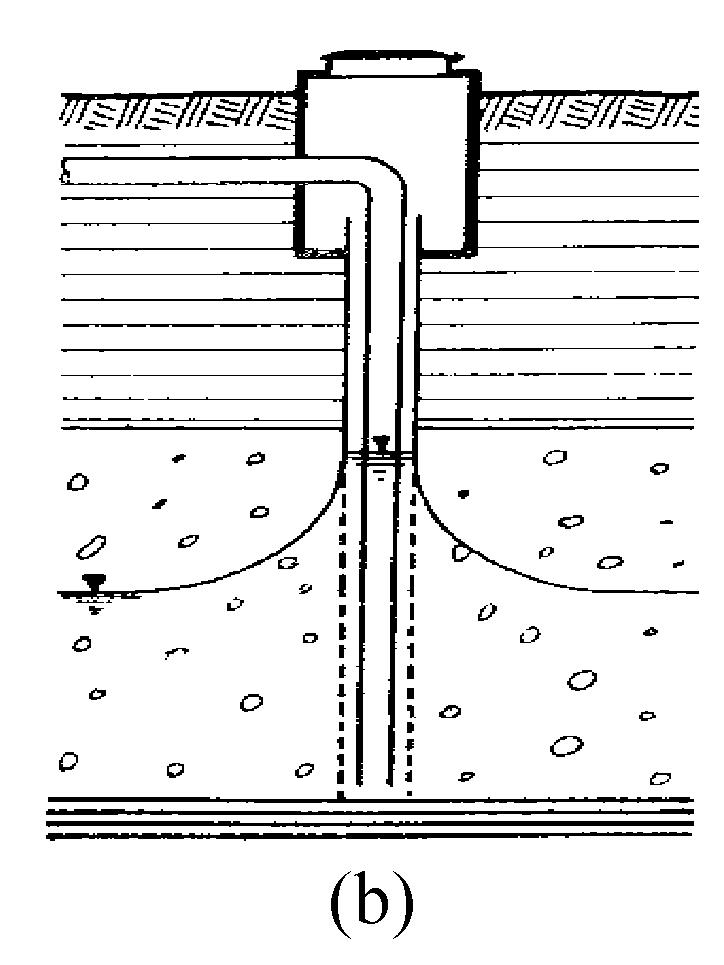

Often infiltration wells are in use, dug wells (Fig.7a) for shallow aquifers and drilled wells (Fig.7b) for deeper located aquifers.

Fig. 7.

Dug well (a) and drilled well (b) for infiltration (ORL-ETHZ, 1970)

Example: Waterwork Wiesbaden-Schierstein, Germany

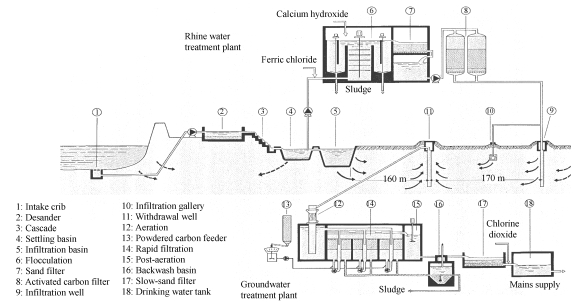

The Waterwork Wiesbaden-Schierstein, Germany, is an example of a plant applying artificial groundwater recharge by using infiltration basins, infiltration wells, infiltration pipes and extraction wells in connection with water treatment plants (Fig.8). The raw water is extracted from the Rhine River. It passes a sedimentation basin, a cascade and flows into infiltration basins. A certain part of the water is pumped to a water treatment plant, treated by flocculation and filtration, and then infiltrated into the aquifer by infiltration wells and infiltration pipes. After a subsurface passage, the artificially recharged groundwater is extracted from the aquifer by wells. Finally, a rapid sand filtration and a slight addition of chlorine dioxide, in order to avoid a growing up of microorganisms in the distribution network, complete the water treatment.

Fig. 8.

Water course during the artificial and natural treatment (Waterwork Wiesbaden-Schierstein, Germany)

But it has to be taken into consideration that normally it is sufficient to use only one infiltration and purification technique, and a final water treatment with chlorine dioxide (ClO2) can be added in cases of emergency. In order to increase the efficiency of the system, especially in cases of increased pollution of the surface water, it can be useful to combine artificial groundwater recharge with some other techniques of water treatment by natural purification.

PRE-FILTRATION

Pre-filtration is the filtration of water before the artificial groundwater recharge. It takes place in shallow basins with an impermeable bottom made, e.g., of concrete, which are filled with a layer of gravel and sand of about 1 m thickness as filter material. Entering over a cascade, the water flows horizontally through the filter layer to a collector pipe located at the opposite side of the basin. During the passage, the purification processes described in Section 2 take place. Finally, the water is conducted to slow sand filtration basins where artificial groundwater recharge happens by vertical seepage of the water.

BANK FILTRATION

Artificial bank filtration (Fig.9) is the extraction of river or lake water by wells that are located near the bank of the surface water (Firch and Wichmann, 2005). At adjusted pumping rates, the hydraulic gradient between the surface water level and the lowered groundwater level at the well is directed towards the well. In this way, surface water is forced to flow into the aquifer and finally into the well. The well extracts a mixture of surface water and groundwater.

Fig. 9.

Scheme of bank filtration

The portion of surface water that contributes to the extracted water depends on the permeability of the river bed and the aquifer. The quality of the extracted water as a mixture of surface water and groundwater is especially influenced by the properties of the surface water and the efficiency of natural attenuation during the passage in the subsurface. The purification processes are the same as described in Subsection 2.1.

For the extraction of surface water also collector wells can be applied. They consist of a shaft of 2 to 5 m in diameter and horizontally installed screen strings of 10 to 50 m length. The screens can be positioned below the river or lake. With such wells large quantities of water can be extracted.

PLANT PURIFICATION PLANTS

A plant purification plant consists of shallow basins that are equipped with special aquatic plants. The purification of more or less polluted water flowing through the basins is executed by bacteria that are located at the roots of the aquatic plants and within the soil. Because a relatively large area is needed for such a treatment, a combination with artificial groundwater recharge is possible but restricted to cases with small water need.

SUBSURFACE DAMS

In regions with dry seasons it may be advantageous to construct a subsurface dam for the storage of the groundwater contained in the unconsolidated rocks below an ephemeral river (Fig.10). Especially in narrow river valleys where loose sediments of sand and gravel are underlain by more or less impervious bedrock in shallow depths, this method can be very advantageous.

Fig. 10.

Scheme of a subsurface dam

The subsurface barrier can be build up with bricks or concrete. The upper crest of the dam should be located about 1 m below the level of the river bed. Upstream the subsurface dam, a discharge well has to be located and, if water can be brought up from adjacent areas, infiltration wells may be added.

ARTIFICIAL AQUIFERS

In mountainous areas artificial aquifers can be established in narrow valleys of brooks and rivers. For this purpose, small dams of 3 to 5 m height are built up in the valley for retaining sediment which is transported by the river during flood periods. After the open space upwards the dam is filled up with sand and gravel, the water stored in the pore space of this sediment can be used. Compared with an open water reservoir, the storage capacity is reduced to 20%~30% of the whole space. But on the other hand, evaporation is reduced and water can be stored for a longer period. Discharge pipes with valves installed in the dam at different levels, allow the withdrawal of water in a controlled way and adjusted to the need.

CONCLUSION

Artificial groundwater recharge is practiced for many purposes: drinking water production, improvement of raw water quality, storage of fresh water, aquifer recovery, infiltration of storm water runoff, preservation of natural wetland, disposal of treated sewage effluents, formation of hydraulic barriers against sea water intrusion.

Artificial groundwater recharge is a successful method in order to purify surface water and to improve the water management. The great variability of infiltration, extraction and purification methods allows several combinations and adapted designs for various hydrological, hydrogeological and hydrochemical situations as well as for various water requirements.

Compared with other methods of water treatment, artificial groundwater recharge is ecologically sustainable and cheaper than chemically induced coagulation, ozone floc filtration, the application of reverse osmosis, ultraviolet beams, ultra-filtration, or activated charcoal.

Artificial groundwater recharge has proved very successful at many sites in Germany over a period of more than 100 years.

References

- 1.Balke KD. Investigation of the Groundwater Resources in the Irrigation Area West of Ismailia/Egypt. Part I. Vol. 4. Stuttgart: 1990. ISBN 3-443-01014-8 (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balke KD. Surplus or Absence of Chemical Components in Water and Its Consequences for Public Health. In: Balke KD, Zhu Y, editors. Water and Development. Beijing, China: Geology Press; 2003. pp. 36–42. ISBN 7-116-03831-0/X·17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balke KD. Water Supply by Bank Filtration and Artificial Groundwater Recharge. In: Balke KD, Zhu Y, Prinz D, editors. Water and Development II. Beijing, China: Geology Press; 2004. pp. 18–25. ISBN 7-116-04217-2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balke KD, Griebler C. Groundwater Use and Groundwater Protection. In: Griebler C, Mösslacher F, editors. Groundwater Ecology. Wien: Facultas UTB; 2003. p. 495. ISBN 3-8252-2111-3(in German) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balke KD, Zhu Y. Sources of Water Pollution. In: Balke KD, Zhu Y, editors. Water and Development. Beijing, China: Geology Press; 2003. pp. 3–9. ISBN 7-116-03831-0/X·17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balke KD, Beims U, Heers FW, et al. Groundwater Exploitation. Hydrogeological Textbook. Vol. 4. Berlin-Stuttgart: 2000. p. 740. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Firch M, Wichmann K. Influence of Limiting Factors upon the Purification Capacity of an Optimized Bank Filtration. Final Report of the Project B5 of the BMBF-Research Project Export-Oriented Research and Development in the Field of Water Supply and Sewage. Part I: Drinking Water. Technical University Hamburg-Harburg; 2005. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 8.ORL-ETHZ (Swiss Technical University, Zuerich, Switzerland) Guideline for Artificial Groundwater Recharge. Zuerich: 1970. p. 516023. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preuß G, Schulte-Ebbert U. Artificial Groundwater Recharge and Bank filtration. In: Rehm HJ, Reed G, editors. Biotechnology. Vol. 11c. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2000. pp. 425–444. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Remmler F, Schulte-Ebbert U. Development of understanding the process of self-purification of groundwater. Vom Wasser. 2003;101:77–90. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt H. Groundwater Recharge and Water Production. Zbl. Bakt. Hyg. I, Abt. Orig. B. 1980. pp. 134–155. (in German) [PubMed]

- 12.Schmidt H, Balke KD. Possibilities of artificial groundwater recharge and storage in the Federal Republic of Germany. Z Dt Geol Ges. 1980;131:93–109. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt H, Balke KD. Requirements and Registration of Sites for Artificial Groundwater Recharge in the Federal Republic of Germany. Berlin: 1985. p. 186. UBA-FB 80-179 (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolters N, Hantke H. Experiments with infiltration methods in the hessian ried area. DVWK-Bulletin. 1982;14:97–118. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu Y, Balke KD. The Coastal Areas of China, Proceedings Con. Soil. Bordeaux: 2005. Practical Operating Approach to Urban Groundwater Management; pp. 301–305. [Google Scholar]