Abstract

Bcl-2 family proteins can be classified into two subfamilies – anti-apoptotic members and pro-apoptotic members. Mechanistically, these two subfamilies can antagonize each other through heterodimerization while homodimerization have been proposed for each subfamily to carry out their corresponding anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic functions. To date, many small-molecule antagonists against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins have been developed, which are monomeric modulators. In this study, a series of BH3I-1 based dimeric modulators were developed with structure-activity relationship explored. Dimeric modulators compared to the monomeric antagonists have enhanced binding activity against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. In addition, the acidic functional group was demonstrated to be critical for the binding interaction of the small-molecule antagonists with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. Finally, the representative dimeric modulator revealed enhanced activity in inducing cytochrome c release from mitochondria compared to its monomeric counterpart. Taken together, dimerization of monomeric modulators is one practical approach to enhance the bioactivity of Bcl-2 antagonists.

Keywords: Bcl-2, apoptosis, BH3I-1, dimeric, modulator

Drug resistance is a major challenge in cancer chemotherapy.1 The over-expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins which protect cells from apoptosis is one mechanism for tumors to acquire drug resistance.2-4 Inhibiting anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, therefore, is one promising strategy to nullify drug resistance in cancer treatment, which has been proved valid through anti-sense approach.5 Mechanistically, anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins protect cells from apoptosis by antagonizing pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins through dimerization.6,7 Structural studies of a complex of Bcl-XL protein and a pro-apoptotic peptide (Bak BH3) have revealed a hydrophobic cleft on Bcl-XL protein as the binding pocket for the pro-apoptotic peptide8 and molecules binding to that hydrophobic cleft may overcome the protective effect of the Bcl-XL protein.9 These observations have stimulated the recent discovery of small-molecule based antagonists - a few of which are currently at various stages of clinical evaluation, such as gossypol, apogossypol, TW-37, and ABT-737.10-14

As Bcl-2 proteins form homo/hetero oligomers for their physiological functions, multivalent modulators may potentially possess unique functions that are not present in the monomeric modulators.15 In addition, it is well established that multivalency of ligands could enhance potency compared to the monomeric ones.16,17 To test these concepts in the Bcl-2 protein family, we developed a series of dimeric analogs of 3e based on BH3I-1, a small-molecule Bcl-2 antagonist developed by Degterev et al.18 Several dimeric modulators demonstrated enhanced potency to inhibit the binding of a BH3-domain Bak peptide binding to the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins while dimerization through the carboxylic acid group on 3e resulted in substantial loss of the activity. Further SAR studies confirmed that the carboxylic acid was critical for the antagonism of the small molecule against the Bcl-2 proteins. The enhanced potency of the dimeric modulators was further confirmed by its ability to induce cytochrome c release from isolated mitochondia. The cytochrome c release study also suggested that the dimeric modulator functionally mimics the monomeric antagonist.

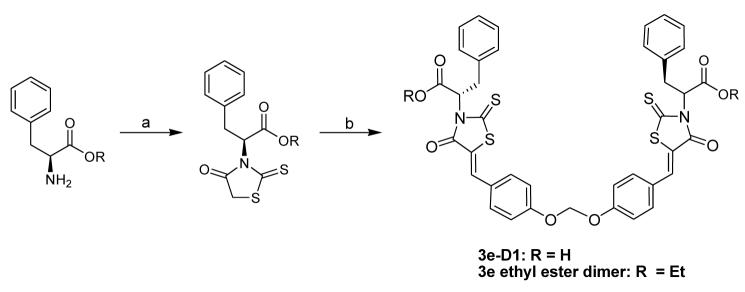

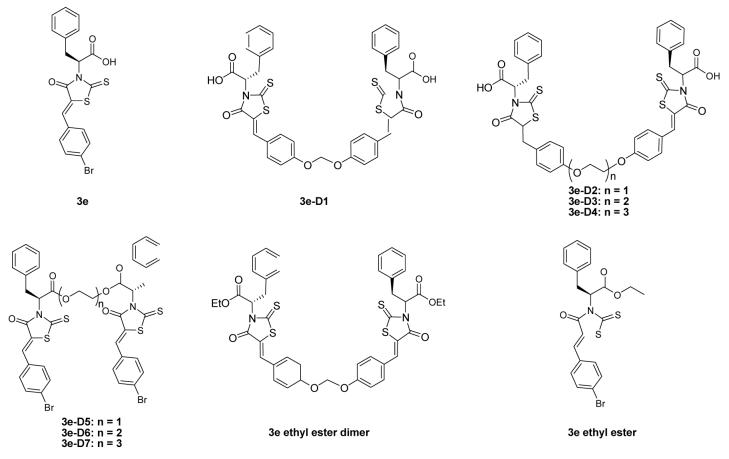

The preparation of the dimeric modulators (3e-D1 – D4 ) followed the general synthetic route outlined in Scheme 1 (The preparation of the dimeric modulators 3e-D5 – D7 followed a similar synthetic route detailed in Supplementary Materials).19 Briefly, the syntheses of 3e-D1 – D4 started with L-phenylalanine, which first reacted with carbon disulfide and cyclized upon chloroacetate treatment to form the rhodanine compound in 45% yield. The rhodanine compound (2.2 equivalent) was then condensed with various dimeric aldehydes in refluxing toluene to afford compound 3e-D1 – D4 in 76-92% yield. These four dimeric analogs were evaluated in the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins binding assays.19 The binding was assessed for their activity to prevent the binding of Bak peptide binding to anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Bcl-w. All of the four dimeric modulators demonstrated improved potency to prevent the binding of Bak peptide to the three anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins tested (Table 1). The best candidate, 3e-D2 demonstrated 5 – 16 fold increase of potency compared to the monomeric 3e. The optimal linker between the monomers is a four-atom ethylene glycolic liner – increase or decrease of linker length would result in decreased activity.

Scheme 1.

General synthetic route for the syntheses of the bottom-linked dimeric modulators. Reagents and conditions: (a) CS2, NaOH; ClCH2COONa; 5.5M HCl, reflux, overnight; (b) 4,4′-[methylenebis(oxy)]bis Benzaldehyde (0.45 equivalent), NH4OAc in Toluene, reflux, 16h. (For the syntheses of 3e-D2, D3, and D4, 4,4′-Ethanediyldioxydibenzaldhyde, 4,4′-(3-Oxapentanediyldioxy)dibenzaldehyde, and 4,4′-(3,6-Dioxaoctanediyldioxy)dibenzaldehyde were used respectively instead of 4,4′-[methylenebis(oxy)]bis Benzaldehyde).

Table 1.

The inhibitory potency of BH3I-1 based modulators against Bak peptide binding to anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins.

| Ki (μM)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bcl-2 | Bcl-XL | Bcl-w | |

| 3e | 14.2 | 5.25 | 21.5 |

| 3e-D1 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| 3e-D2 | 1.7 | 0.97 | 1.3 |

| 3e-D3 | 4.3 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| 3e-D4 | 21.2 | 8.7 | 13.7 |

| 3e-D5 | 243 | 134 | 101 |

| 3e-D6 | >1000 | 104 | 99 |

| 3e-D7 | 161 | 112 | 88.3 |

| 3e-dimer ethyl ester | 226 | 58.4 | 39.2 |

| 3e ethyl ester | 260 | 176 | 116 |

Values (Ki) are given as an average of 3 experiments with triplicate performed in each individual experiment.

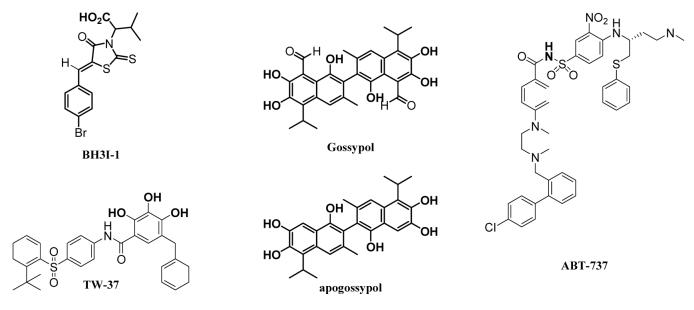

Delighted by these results, we further explored the other dimerization of the monomeric 3e. 3e-D5 – D7 were prepared by using L-phenylalanine based rhodanine, which first reacted with various ethylene glycol to form the dimeric rhodanines in 34 – 81% yield (Supplementary Materials). The dimeric rhodanines were then condensed with 5-bromobenzaldehyde (2.2 equivalent) for 3e-D5 – D7 (82 – 95%). These three dimers, however, all demonstrated substantial decrease of potency to prevent Bak peptide binding to anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (Table 1). One potential cause for the loss of activity would be due to the mask of the carboxylic acid functional group on 3e. To test this hypothesis, we synthesized 3e ethyl ester and 3e ethyl ester dimer by following the same procedure for the preparation of 3e19 and 3e-D1 except that the ethyl ester of L-phenylalanine was used instead of L-phenylalanine. As hypothesized, 3e ethyl ester and 3e ethyl ester dimer all demonstrated substantially weakened ability to prevent Bak peptide binding to the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins relative to 3e (> 5 fold loss) and 3e-1D (> 15 fold loss) respectively. 3e ethyl ester dimer still revealed better potency than the monomeric 3e ethyl ester. These SAR studies demonstrate the carboxylic acid functional group on 3e is critical for its interaction with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. In fact, quite a few of the reported small-molecule antagonists against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins have acidic functional groups, such as gossypol, apogossypol, ABT-737, TW-37, and the recent flavonoid compound developed by Wang et al (The acidic protons are highlighted in Figure 1). Wang et al also observed that masking the acidic functional group resulted in dramatic loss of the activity against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins.20,21 Our study herein, in combination with the other studies, suggest that an acidic functional group may be optimal for small-molecule antagonists against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins.

Figure 1.

Structures of some reported small molecule antagonists against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (the acidic protons are highlighted).

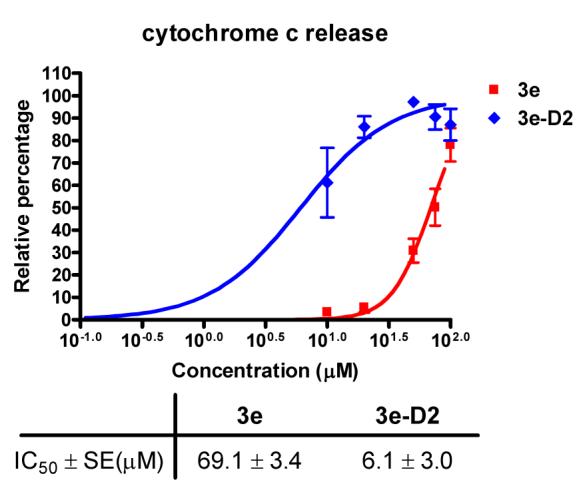

To explore whether the monomeric modulator and dimeric modulator may function differently, we evaluated 3e and 3e-D2 for their ability to induce cytochrome c release from mitochondria, a key feature for mitochondrial-mediated apoptotic cascade. Both candidates induced cytochrome c release from the isolated mitochondria (Figure 3). The respective concentration to induce 50% cytochrome c release for 3e was about 69 μM while that for 3e-D2 was ∼ 6 μM, correlating with their potency to antagonize the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins.

Figure 3.

The potency of 3e and 3e-D2 in releasing cytochrome c from isolated mitochondria.

In summary, dimerization of monomeric antagonist 3e could enhance the potency to bind the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. The dimeric modulator also had enhanced activity to induce cytochrome c release from mitochondria. These studies demonstrated the dimerization is an effective approach to enhance the potency of Bcl-2 antagonists. In addition, our SAR studies in combination with others suggest that an acidic functional group is critical for the antagonism of the small molecules against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. Our current studies also suggest that the dimeric modulators have the same function as the monomeric antagonists.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Structures of BH3I-1 based monomeric modulators and dimeric modulators against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Reed JC, Miyashita T, Takayama S, Wang HG, Sato T, Krajewski S, Aime-Sempe C, Bodrug S, Kitada S, Hanada M. J. Cell. Biochem. 1996;60:23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960101)60:1%3C23::AID-JCB5%3E3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiechle FL, Zhang X. Clin. Chim. Act. 2002;326:27. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folkman J. Semi. Cancer Biol. 2003;13:159. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reinhold WC, Kouros-Mehr H, Kohn KW, Maunakea AK, Lababidi S, Roschke A, Stover K, Alexander J, Pantazis P, Miller L, Liu E, Kirsch IR, Urasaki Y, Pommier Y, Weinstein JN. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan SL, Lee MC, Tan KO, Yang L, Lee ASY, Flotow H, Fu NY, Butler MS, Soejarto DD, Buss AD, Yu VC. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reed JC. Oncogene. 1998;17:3225. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams JM, Cory S. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:61. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sattler M, Liang H, Nettesheim DN, Meadows RP, Harlan JE, Eberstadt M, Yoon HS, Shuker SB, Chang BS, Minn AJ, Thompson CB, Fesik SW. Science. 1997;275:983. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holinger EP, Chittenden T, Lutz RJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim R, Tanabe K, Emi M, Uchida Y, Toge T. Cancer. 2005;103:2199. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitada S, Leone M, Sareth S, Zhai D, Reed JC, Pellecchia M. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:4259. doi: 10.1021/jm030190z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, Armstrong RC, Augeri DJ, Belli BA, Bruncko M, Deckwerth TL, Dinges J, Hajduk PJ, Joseph MK, Kitada S, Korsmeyer SJ, Kunzer AR, Letai A, Li C, Mitten MJ, Nettesheim DJ, Ng S, Nimmer PM, O'Connor JM, Oleksijew A, Petros AM, Reed JC, Shen W, Tahir SK, Thompson CB, Tomaselli KJ, Wang B, Wendt MB, Zhang H, Fesik SW, Rosenberg SH. Nature. 2005;435:677. doi: 10.1038/nature03579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanabe K, Kim R, Inoue H, Emi M, Uchida Y, Toge T. Int. J. Oncol. 2003;22:875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Liu D, Zhang Z, Shan S, Han X, Srinivasula SM, Croce CM, Alnemri ES, Huang Z. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:7124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clackson T, Yang W, Rozamus LW, Hatada M, Amara JF, Rollins CT, Stevenson LF, Magari SR, Wood SA, Courage NL, Lu X, Cerasoli F, Jr., Gilman M, Holt DA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:10437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Z, Merritt EA, Ahn M, Roach C, Hou Z, Verlinde CLMJ, Hol WGJ, Fan E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12991. doi: 10.1021/ja027584k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green NS, Palaninathan SK, Sacchettini JC, Kelly JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13404. doi: 10.1021/ja030294z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degterev A, Lugovskoy A, Cardone M, Mulley B, Wagner G, Mitchison T, Yuan J. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:173. doi: 10.1038/35055085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xing C, Wang L, Tang X, Sham Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:2167. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.12.020. The general experimental procedure for preparing the BH3I-1 based antagonists is described below with the synthesis of analog 3e-D1 as an example. In a round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer, L-phenylalanine (1 mmol) was dissolved with sodium hydroxide (80 mg, 2 mmol) in water (10 ml). Then, carbon disulfide (60 μl, 1 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture, which was stirred vigorously overnight. An aqueous solution of ClCH2CO2Na (1 ml, 1 M, 1 mmol) was added and stirring was continued at 23 °C for 3 hours. Then hydrochloric acid solution (3 ml, 5.5 N, 16.5 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was refluxed overnight. The reaction mixture was neutralized with saturated NaHCO3 solution. The solvent was removed under vacuum and the cyclized product was purified by flash chromatography. In a round-bottom flask equipped with a reflux condenser and a magnetic stirrer, cyclized rhodanine intermediate (1 mmol) in toluene (20 ml) was added. To this, 4,4′-[methylenebis(oxy)]bis Benzaldehyde (0.45 mmol) was added along with ammonium acetate (3 mmol). The mixture was refluxed overnight and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The final rhodanine candidate was purified by flash chromatography. 3e-D1 (54%) Yellow powder. TLC (CH2Cl2 / MeOH = 9:1), Rf 0.18. m.p. 242–3 C°. IR (KBr, γmax, cm−1): 3700-2200, 2923, 2852, 1695, 1590, 1506, 1344, 1273, 1239, 1218, 1170, 999 cm−1. 1HNMR (CDCl3): 7.60(2H, s, 4-H, 4'-H), 7.40(4H, d, J=9Hz, 10-H, 11-H, 10'-H, 11'-H), 7.30-7.10(14H, m, 5-H, 6-H, 7-H, 8-H, 9-H, 12-H, 13-H, 5'-H, 6'-H, 7'-H, 8'-H, 9'-H, 12'-H, 13'-H), 6.10(2H, t, J=6.9Hz, 2-H, 2'-H), 5.81(2H, s, 1-H), 3.62(4H, d, J=6.9Hz, 3-H, 3'-H) ESI-MS (negative): m/z 446, 448 (M−-H); 402, 404 (M−-H-CO2). ESIMS (m/z, negative): 781(M-1). The binding assay of small-molecule antagonists to anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins was run essentially as described in. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Wang R, Fang X, Pan H, Tomita Y, Li P, Roller PP, Krajewski K, Saito NG, Stuckey JA, Wang S. Anal. Biochem. 2004;332:261. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.05.055. Human recombinant Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Bcl-w were prepared. To determine the binding affinity of small molecules for an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein, a series of 3-fold dilutions of small molecules were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide, i.e., 10 mM, 3.33 mM, 1.11 mM, 0.37 mM, 0.123 mM, 0.041 mM, 0.014 mM, and 0 mM. To each well in a 96-well half-area black plate, 5 μl of the small molecule stock solution was added. A solution containing 50 nM Flu-Bak peptide and the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein to be tested in PBS buffer, pH 7.0, 1 mM DTT was prepared and incubated at 23 °C for one hour. The concentration of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein used corresponds to the one that resulted in 60% of Flu-Bak peptide complex with the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein and such a concentration was determined in the Flu-Bak and Bcl-2 protein saturation binding experiment. The corresponding concentrations of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Bcl-w needed to achieve 60% complex formation under the assay conditions are 1000 nM, 880nM, and 1200 nM respectively. To each well the Flu-Bak peptide and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein solution (45 μl) was added by auto-injection at a rate of 200 μl/second. The sample was incubated at 23 °C for one hour and shaken for two seconds before fluorescence polarization (in mP unit) was measured. Controls included dose-response measurements in the absence of proteins to assess for any interactions between the compounds and the Flu-Bak peptide. Eventual effects were taken into account by subtraction. The inhibitory constant (Ki) was determined by fitting the FP changes to the concentration of the small molecule competing ligand by using an equation developed in. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Frezza C, Cipolat S, Scorrano L. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:287. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.478. For cytochrome c release, mitochondria was isolated from mouse liver using differential centrifugation for incubation with exogenous proteins as described by. Briefly, livers were removed from euthanized animals and immersed in isolation buffer, IBc (10mM Tris-MOPS, 1mM EGTA/Tris, 0.2M sucrose, pH 7.4). Samples were washed 5 times with IBc to remove excess blood and minced on ice in IBc. The tissue was then homogenized in a glass potter using a Teflon pestle for 4 strokes in fresh IBc. The homogenate was centrifuged at 600g for 10 minutes at 4 °C in a JA 25.4 rotor (Beckman). The supernatant was then centrifuged at 7,000g for 10 minutes to pellet mitochondria. The pellet was washed in fresh IBc. The final pellet was resuspended in a small amount of IBc. Samples were quantified by Bradford and diluted to 1mg/ml in experimental buffer, EBc (125mM KCl, 1mM Tris/MOPS, 0.1mM EGTA/Tris, 0.1mM KH2PO4). Isolated mitochondria were incubated with increasing concentrations of Monomer and Dimer solubilized in DMSO. All samples contained an equal concentration of DMSO. Mitochondria were incubated for 1 hour at 30 °C, after which the membranes were spun at 13,000g in a microcentrifuge for 10 minutes to pellet mitochondria. Samples from the supernatant and pellet were run on a 10% Tricene gel and immunoblotted for cytochrome c using a sheep anti-cytochrome c antibody (Ex Alpha Biologicals). Percent cytochrome c release was determined using ImageQuant 5.2 (Molecular Dynamics) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang G, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Yang CY, Wang R, Tang G, Guo J, Shangary S, Qiu S, Gao W, Yang D, Meagher J, Stuckey J, Krajewski K, Jiang S, Roller PP, Abaan HO, Tomita Y, Wang S. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:6139. doi: 10.1021/jm060460o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang G, Ding K, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Yang CY, Qiu S, Shangary S, Wang R, Guo J, Gao W, Meagher J, Stuckey J, Krajewski K, Jiang S, Roller PP, Wang S. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:3163. doi: 10.1021/jm070383c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.