Abstract

Context: Sex steroid hormones potentiate whereas increased body mass index (BMI) represses GH secretion. Whether sex steroids modify the negative effect of BMI on secretagogue-induced GH secretion in men is not known. The issue is important in designing GH-stimulation regimens that are relatively insensitive to both gonadal status and adiposity.

Objective: Our objective was to compare the relationships between BMI and peptide-stimulated GH secretion in men with normal and reduced testosterone and estradiol availability.

Setting: The study was performed at an academic medical center.

Subjects: Healthy young men were included in the study.

Interventions: Randomized separate-day iv infusion of saline and/or maximally effective doses of L-arginine/GHRH, L-arginine/GH-releasing peptide (GHRP)-2, and GHRH/GHRP-2 in eugonadal (n = 12) and experimentally hypogonadal (n = 10) men was performed.

Outcomes: Regression of paired secretagogue-induced GH responses on BMI was determined.

Results: In eugonadal men, peak GH concentrations correlated negatively with BMI. In particular, BMI accounted for only 38% of the response variability after L-arginine/GHRH (P = 0.0165), but 62% after GHRH/GHRP-2 (P = 0.0012) and 65% after L-arginine/GHRP-2 (P = 0.00075). In contrast, in hypogonadal men, GH responses were uncorrelated with BMI. The negative effects of BMI on peak GH responses in eugonadal and hypogonadal states differed most markedly after stimulation with GHRH/GHRP-2 (P = 0.0019). This contrast was corroborated using integrated GH responses (P = 0.0007).

Conclusions: Short-term experimental gonadal sex hormone depletion attenuates dual secretagogue-stimulated GH secretion in lean young men. The inhibitory effect of relative adiposity on GH secretion appears to predominate over that of acute sex steroid withdrawal.

Designing GH-stimulation regimens is complicated by the fact that sex hormones potentiate GH secretion whereas increased body mass index (BMI) represses GH secretion. This study shows that short-term sex-steroid withdrawal in lean, young men attenuates dual secretagogue-stimulated GH secretion, suggesting that the inhibitory effect of relative adiposity on GH secretion predominates over that of acute sex-steroid withdrawal.

Body mass index (BMI) and other indices of fat burden correlate negatively with pulsatile GH secretion and GH responses to individual secretagogues (1,2,3,4,5). Whether the same relationship applies to combined secretagogue stimulation in healthy men is not known, except in the case of L-arginine/GHRH (6). In mechanistic terms, the negative impact of adiposity is mediated via attenuation of the size rather than the number of GH secretory bursts (1,7). The size of GH pulses is governed in turn by interactions among the agonistic peptides, GHRH and ghrelin [a GH-releasing peptide (GHRP)], and the inhibitory peptide, somatostatin (8,9,10,11,12,13). Interactive or ensemble control of GH secretion has been documented experimentally by demonstrating that transgenic silencing of any one of GHRH, ghrelin, or somatostatin receptors alters regulation of GH secretion by the other two peptides (8,9). Clinical and analytical models of ensemble control of GH secretion illustrate the plausible basis for three-peptide interactions (13,14,15). Nonetheless, how BMI modulates such interactions is not known (2).

Testosterone (Te) and estradiol (E2) stimulate pulsatile GH secretion, augment the amount of GH secreted per burst, and elevate total IGF-I concentrations (2,16,17,18). Conversely, chronic reductions in Te and E2 concentrations decrease pulsatile GH secretion (2). In contradistinction, whether short-term hypogonadism depresses secretagogue-stimulated GH secretion remains uncertain. Moreover, whether BMI modulates the effects of sex hormones on multipeptide control of GH secretion is unknown, although androgens and BMI jointly determine GH secretion in multivariate regression analyses (2,3,19,20,21). These questions are significant, inasmuch as: 1) BMI varies widely among otherwise healthy subjects, 2) no single secretagogue or inhibitory peptide acts alone or may be considered alone in directing GH secretion, 3) hypogonadism is a common outcome of both acute and chronic pathophysiologies (22,23,24), and 4) increased BMI and hypogonadism may occur in the same individual (25). For example, protracted critical illness, sepsis, cardiorespiratory failure, trauma, cachexia, uncontrolled diabetes, and other multisystem diseases reduce testicular steroidogenesis (26).

One approach to dissecting how BMI and secretagogues interact with gonadal sex steroids is the use of clinical paradigms of short-term sex steroid deprivation (27,28,29). Gonadal suppression models obviate the confounding effects of inflammation, hypoxia, acidosis, infection, and organ failure otherwise present in critical illness (30). Accordingly, the present investigation uses a clinical model of GnRH agonist-induced hypogonadism to test the hypothesis that the systemic availability of gonadal sex steroids and relative adiposity together control GH responses to dual secretagogues. Paired secretagogues were selected a priori to facilitate dissection of response pathways. In particular, combined stimulation with GHRH and GHRP-2 provides a measure of two-peptide synergy, L-arginine/GHRP-2 permits an estimate of GHRP-2 efficacy, and L-arginine/GHRH confers an index of GHRH efficacy (13,15).

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Volunteers provided written informed consent approved by the Mayo Institutional Review Board and reviewed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration under an investigator-initiated new drug number. Exclusion criteria were: exposure to psychotropic or neuroactive drugs within five elimination half-lives; BMI less than 18 and more than 32.5 kg/m2; anemia (hemoglobin < 12.8%); drug or alcohol abuse, psychosis, depression, mania, or severe anxiety; acute or chronic organ-system disease; use of Te, other anabolic steroids, or glucocorticoids; endocrinopathy, other than primary thyroidal failure receiving replacement; nightshift work or recent transmeridian travel (exceeding three time zones within 7-d admission); acute weight change (loss or gain of > 2 kg in 6 wk); allergy to administered peptides; and unwillingness to provide written informed consent. Each subject had an unremarkable medical history and physical examination, and normal screening laboratory tests of hepatic, renal, endocrine, metabolic, and hematological function. The men reported normal sexual development and function.

Protocol

There were 10 healthy young men that received two consecutive injections of depot leuprolide acetate (3.75 mg im 3 wk apart) to deplete systemic Te and E2 concentrations. Secretagogue infusions were scheduled 10–18 d after the second dose of leuprolide. There were 12 other young men not given leuprolide. Each subject was studied three times in the Clinical-Translational Research Unit (CRU). Admissions were scheduled at least 48 h apart on separate mornings after a standardized overnight fast.

The study design was a parallel cohort, double blind, and prospectively randomized. Subjects were admitted to the CRU before 1700 h and stayed overnight, or arrived by 0630 h on the day of infusion. To limit nutritional confounds, a constant meal (vegetarian or nonvegetarian) was given to ingest at home or in the CRU at 1800 h the night before the study comprising 8 kcal/kg distributed as 50% carbohydrate, 20% protein, and 30% fat. Volunteers then remained fasting, alcohol abstinent, and caffeine-free overnight until the end of the infusion the next day.

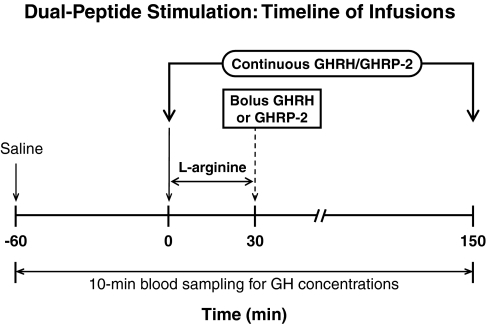

In the CRU, iv catheters were placed into contralateral forearm veins at 0700 h to allow simultaneous infusion of secretagogues and blood sampling every 10 min beginning at 0800 h on separate days at least 48 h apart. Sampling consisted of a 1-h baseline and 2.5-h post-infusion interval. Intravenous infusions comprised: 1) combined GHRH and GHRP-2 delivery both at a constant rate of 1 μg/kg·h; 2) L-arginine 30 g over 30 min, followed immediately by 1 μg/kg bolus GHRH (GEREF; Serono, Norwalk, MA); and 3) L-arginine as in step 2, followed by 3 μg/kg bolus GHRP-2 (Fig. 1). These doses of L-arginine and peptides are maximally stimulatory in adults (31,32,33). L-arginine was used to antagonize GH autofeedback-induced somatostatin outflow (34,35).

Figure 1.

Time line of sequential iv infusion of maximally stimulatory doses of L-arginine (30 g over 30 min) and bolus GHRH (1 μg/kg) or GHRP-2 (3 μg/kg), and combined continuous iv infusion of GHRH and GHRP-2 (both 1 μg/kg·min for 150 min).

Blood was also withdrawn at 0800 h for later assay of serum E2, Te, LH, FSH, IGF-I, IGF binding protein (IGFBP)-1, IGFBP-3, and SHBG concentrations. Lunch was provided after sampling before discharge from the CRU.

Remuneration

Study participants were given $450.00 each as institutional review board-approved reimbursement for time spent in the outpatient and inpatient visits.

Hormone assays

Serum GH concentrations were determined in duplicate by automated ultrasensitive double-monoclonal immunoenzymatic, magnetic particle-capture chemiluminescence assay using 22-kDa recombinant human GH as assay standard (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur Access, Chaska, MN). Sensitivity is 0.010 μg/liter (defined as three sd values above the zero-dose tube). Interassay coefficients of variation (CVs) were 7.9 and 6.3% at GH concentrations of 3.4 and 12 μg/liter, respectively. Intraassay CVs were 4.9% at 1.1 μg/liter and 4.5% at 20 μg/liter. No values decreased to less than 0.020 μg/liter. Cross-reactivity with 20-kDa GH is less than 5% on a molar basis. Te concentrations were quantitated by automated competitive chemiluminescent immunoassay (ACS Corning, Bayer, Tarrytown, NY). Mean intraassay and interassay CVs were 6.8 and 8.3%, with an assay sensitivity of 8 ng/dl (multiply by 0.0347 for nmol/liter) (18). E2 was measured by double-antibody RIA (Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA). Intraassay CVs are 18.3% at 3.6 pg/ml, 3.8% at 40 pg/ml, and 7.2% at 297 pg/ml. Interassay CVs are 8.1, 4.7, and 4.9% at 16.0, 31, and 119 pg/ml, respectively (multiply by 3.47 for pmol/liter). IGFBP-1, IGFBP-3, and total IGF-I concentrations were measured by immunoradiometric assay (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX) (18,36). Interassay CVs for IGF-I were 9% at 64 μg/liter and 6.2% at 157 μg/liter. Intraassay CVs were 3.4% at 9.4, 3% at 55, and 1.5% at 264 μg/liter.

Statistical analysis

Two-way ANOVA (2 × 3 factorial design) was used to examine the individual and interactive effects of normal vs. low Te/E2 (two factors) and secretagogue type (three factors) on: 1) peak GH concentrations (μg/liter); and 2) integrated GH concentrations over 2.5 h after secretagogue infusion (μg/liter × min). Post hoc contrasts were made via Tukey’s honestly significantly different test (37). Linear regression analysis was applied to examine the relationship between peak or integrated GH concentrations and BMI in the two separate cohorts. Slopes in the two groups of subjects were compared by z-score transformation using the pooled sem adjusted for group size. An unpaired Student’s t test was used to compare baseline (unstimulated) hormone concentrations in the two groups.

Data are presented as the mean ± sem. Experiment-wise P < 0.05 was construed as statistically significant.

Statistical power analysis

Data from nine studies in hypogonadal or normal males (n = 76 subjects total) indicated that Te supplementation increases mean GH concentrations by a median value of 2.83-fold (absolute range 1.8–4.3) (16,18,38,39,40). Power analysis assumed that Te/E2 depletion exerts an opposite effect of similar relative magnitude [viz. a decrease of (1 − 1/2.83) × 100% or 65%]. For comparison via a one-tailed unpaired Student’s t test at P ≤ 0.05, studying 22 subjects would achieve more than 99, 82, and 98% power to detect a 65% reduction in GH responses to GHRH/GHRP-2, L-arginine/GHRH, and L-arginine/GHRP-2, respectively.

Results

Table 1 summarizes cohort mean age, BMI, and fasting concentrations of GH, LH, FSH, total IGF-I, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-3, E2, Te, and SHBG obtained on the morning of the first infusion. Differences between the groups included lower LH, Te, E2, and IGFBP-1 concentrations in gonadally suppressed than eugonadal men. On the other hand, age, BMI, and concentrations of GH, IGF-I, IGFBP-3, FSH, and SHBG did not differ in the two groups. BMI averaged 25.8 ± 0.92 and ranged from 21–32 kg/m2 in eugonadal men, and 24.8 ± 0.98 with a range from 20–30 kg/m2 in hypogonadal men [P = not significant (NS)]. Individual values are given for all 22 men in the regression plots.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and preinfusion hormone concentrations

| Endpoints | Eugonadal | Hypogonadal | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 22.7 ± 0.71 | 22.8 ± 1.3 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.8 ± 0.92 | 24.8 ± 0.98 | NS |

| LH (IU/liter) | 2.9 ± 0.27 | 1.3 ± 0.33 | 0.002 |

| FSH (IU/liter) | 1.8 ± 0.25 | 2.0 ± 0.38 | NS |

| GH (μg/liter) | 0.60 ± 0.22 | 0.62 ± 0.23 | NS |

| IGF-I (μg/liter) | 384 ± 22 | 425 ± 56 | NS |

| IGFBP-1 (μg/liter) | 21 ± 4.4 | 12 ± 2.7 | 0.05 |

| IGFBP-3 (μg/liter) | 4432 ± 142 | 4560 ± 258 | NS |

| E2 (pmol/liter) | 87 ± 7.3 | 30 ± 3.0 | <0.0001 |

| Te (nmol/liter) | 19 ± 1.7 | 1.8 ± 0.04 | <0.0001 |

| SHBG (nmol/liter) | 20 ± 2.4 | 20 ± 3.0 | NS |

Data are the mean ± sem (n = 12 eugonadal and n = 10 hypogonadal men). P values are one-tailed under the a priori hypothesis that sex steroid deprivation reduces GH-related measures.

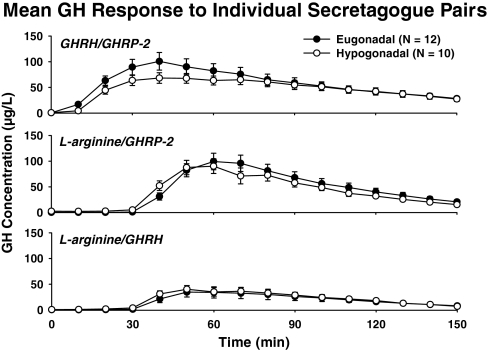

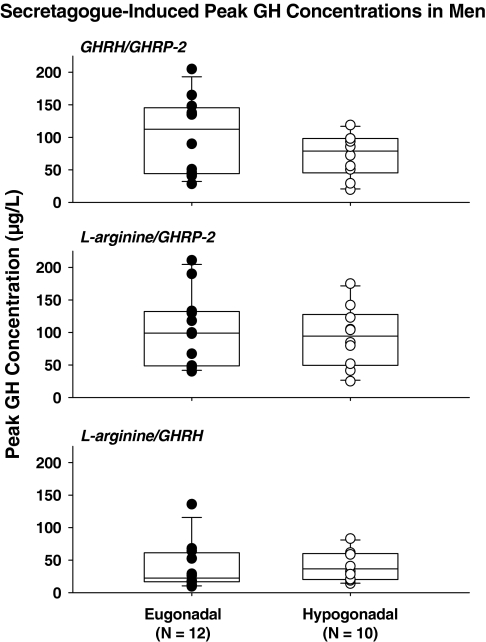

Figure 2 gives mean GH concentration profiles monitored every 10 min for 2.5 h during infusion of L-arginine/GHRH, L-arginine/GHRP-2, and GHRH/GHRP-2. Visual inspection revealed prompt responses to bolus peptide stimuli after priming infusion of L-arginine, and more gradual responses to continuous combined peptide infusion. Two-way analysis of covariance disclosed a significant effect of secretagogue type on peak and integrated GH concentrations (both P < 0.001). In particular, responses to GHRH/GHRP-2 and L-arginine/GHRP-2 were similar, and exceeded those to both L-arginine/GHRH and saline (P < 0.01). The L-arginine/GHRH effect also exceeded that of saline (P < 0.01). There were no significant effects of gonadal status on GH responses (P > 0.05). Unpaired t tests corroborated these inferences (Table 2). To illustrate group responses, Fig. 3 gives box-and-whisker plots that highlight 3- to 6-fold response variability in both cohorts after infusion of each secretagogue pair, raising the question as to what factors contribute to such marked variability.

Figure 2.

Mean GH concentrations monitored every 10 min over 2.5 h during and after iv infusion of GHRH/GHRP-2 (top), L-arginine/GHRP-2 (middle), and L-arginine/GHRH (bottom). Bolus peptide injections were given at 30 min. Data are the mean ± sem (n = 12 eugonadal and n = 10 hypogonadal men).

Table 2.

Comparison of stimulated GH concentrations in all subjects

| Eugonadal (n = 12) | Hypogonadal (n = 10) | t test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak (μg/liter) | |||

| Saline | 1.91 ± 0.753 | 1.98 ± 0.65 | 0.47 |

| GHRH/GHRP-2 | 102 ± 17 | 72 ± 10 | 0.076 |

| L-Arg/GHRH | 39 ± 11 | 42 ± 7 | 0.41 |

| L-Arg/GHRP-2 | 103 ± 16 | 93 ± 15 | 0.34 |

| Integrated (μg/liter × min) | |||

| Saline | 90 ± 33 | 93 ± 35 | 0.47 |

| GHRH/GHRP-2 | 6839 ± 849 | 4169 ± 775 | 0.024 |

| L-Arg/GHRH | 2857 ± 585 | 2160 ± 534 | 0.20 |

| L-Arg/GHRP-2 | 5851 ± 949 | 5878 ± 865 | 0.49 |

Data are the mean ± sem (number as indicated).

Figure 3.

Comparisons between peak stimulated GH concentrations in eugonadal (n = 12) and hypogonadal (n = 10) men after infusion of GHRH/GHRP-2 (top), L-arginine/GHRP-2 (middle), and L-arginine/GHRH (bottom). Data are box-and-whisker plots (median, interquartile, and extreme ranges). Table 2 gives the statistical comparisons.

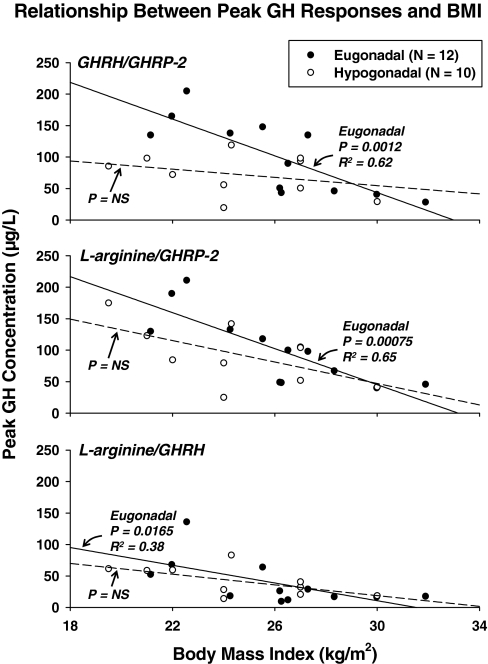

Figure 4 depicts linear regression analyses, wherein secretagogue-induced peak GH concentrations were regressed on BMI in the two cohorts separately. In eugonadal men, BMI correlated negatively with stimulated peak GH concentrations as follows: 1) R2 = 0.65, P = 0.00075 for L-arginine/GHRP-2; 2) R2 = 0.62, P = 0.0012 for GHRH/GHRP-2; and 3) R2 = 0.38, P = 0.0165 for L-arginine/GHRH. The first two regressions are strongly significant at a Bonferroni-protected critical value of P ≤ 0.0165, and explain 62–65% of the variability in peak GH responses in the presence of GHRP-2. In contrast, in hypogonadal men, BMI did not correlate significantly with peak GH concentrations, viz.: 1) R2 = 0.35, P = 0.037 for L-arginine/GHRP-2; 2) R2 = 0.10, P = 0.18 for GHRH/GHRHP-2; and 3) R2 = 0.36, P = 0.034 for L-arginine/GHRH, none of which is significant at protected P ≤ 0.0165. Slope comparisons revealed greater steepness (greater absolute slope values) in eugonadal than hypogonadal men in the case of stimulation with GHRH/GHRP-2 (P = 0.0019).

Figure 4.

Regression of peak secretagogue-stimulated GH concentrations on BMI in sex steroid-deficient (n = 10) and sufficient (n = 12) men. Stimulus pairs are as noted. Numerical values are the square of the correlation coefficient and associated one-tailed P value. P = NS denotes Bonferroni protected P > 0.0167.

To corroborate inferences, integrated GH-concentration responses were also regressed on BMI. Significant negative relationships were observed in eugonadal men after GHRH/GHRP-2 and L-Arg/GHRP-2 stimulation, viz. R2 = 0.64, P = 0.0017 and R2 = 0.52, P = 0.0084, respectively. Comparison of slopes of integrated GH concentrations regressed on BMI in eugonadal and hypogonadal men was significant at P = 0.0007 in the case of GHRH/GHRP-2 synergy.

Discussion

The salient outcomes of this investigation are that: 1) marked gonadal suppression enforced by 35 (±4) d of leuprolide exposure restricts maximal paired-secretagogue drive of GH secretion in lean but not overweight young men; and 2) regression of GHRH/GHRP-2 and L-arginine/GHRP-2-stimulated peak GH concentrations on BMI explains 62 and 65% of agonist-specific response variability in eugonadal men (P < 0.005), but nonsignificantly in hypogonadal men. These data indicate that the attenuating influence of relative adiposity on GH secretory responses may be independent of and dominant over that of an acute reduction in sex steroid availability.

In the case of GHRH/GHRP-2 synergy, the slope of the regression of peak GH responses on BMI was 4.5-fold steeper in eugonadal than hypogonadal individuals (P = 0.0019). This outcome was not biased by evaluating peak GH concentrations because the same relationship applied to integrated values (P = 0.0007). According to a simplified three-peptide model of regulated GH secretion (13,15), the hypogonadism-associated decrease in GH secretion observed in lean men under maximal combined-peptide (GHRH/GHRP-2) drive could reflect reduced efficacy of GHRH and/or GHRP-2, or increased hypothalamic somatostatin restraint. Aging and chronic hypogonadism in men do not consistently diminish the combined efficacies of GHRH and GHRP (2,19,41). In addition, the acute inhibitory effect of a low sex steroid milieu cannot be explained by less secretion of GHRH or endogenous GHRP (ghrelin) because in the dual-peptide paradigm, the effects of variable amounts of endogenous GHRH and ghrelin are replaced by a maximally effective dose of the exogenous peptides. Thus, a more plausible hypothesis would be that experimental depletion of sex steroids for 1 month increases somatostatin outflow in nonobese men.

Previous studies have evaluated the impact of BMI on GH secretion after administration of single but not paired secretagogues (2,4,6,7). An exception is a recent investigation showing that increased BMI restricts GH responses to combined L-arginine/GHRH stimulation in healthy adults (6). The results prompted the suggestion that graded threshold criteria should be applied for GH deficiency when this secretagogue pair is used, namely, a peak GH concentration of 4.2 μg/liter in obese, 8.0 μg/liter in normal weight, and 11.5 μg/liter in lean volunteers. Our data confirm this negative relationship. However, unlike GH responses to GHRH/GHRP-2, we found that responses to L-arginine/GHRH were not reduced additionally by short-term sex steroid depletion. Although the reason for this peptide specificity is not yet evident, GHRPs differ substantially from GHRH by having both GHRH-dependent and GHRH-independent mechanisms of action (2,42).

Administration of the GnRH agonist reduced Te and E2 concentrations to castration levels. Protracted critical illness also decreases Te and E2 concentrations markedly, while suppressing GH, IGF-I, and IGFBP-3 concentrations (22,30). On the other hand, the present model of short-term hypogonadism is not confounded by concurrent effects of inflammation, infection, hypoxia, acidosis, and hepatorenal failure. Therefore, the present data document that short-term reduction of Te/E2 concentrations in lean young men is sufficient, even without superimposed organ-system disease, to impair GHRH/GHRP-2 synergy. Whether lesser noncastration level reductions in Te and E2 concentrations would lead to the same outcome is not known.

One earlier investigation using a GnRH agonist down-regulation model in five young men inferred that the individual effects of GHRH or exercise on GH secretion are preserved in the face of short-term Te/E2 depletion (27). The current investigation differs by examining the impact of short-term gonadal-steroid deprivation on GH responses to paired secretagogues in 22 men with BMI 19–32 kg/m2. Regression of GH responses on BMI revealed that attenuating effects of acute gonadal-hormone withdrawal are observable in lean but not overweight men with a rank order of inferred Te/E2 dependence of GHRH/GHRP-2 = L-arginine/GHRP-2 ≫ L-arginine/GHRH. Accordingly, comparisons of GH secretion in hypogonadal and eugonadal individuals that do not account for strong repression influences of BMI may underestimate or fail to detect sex steroid effects.

Regression analyses predicted that overweight/obese men (BMI 30 kg/m2) have lower GH responses than lean men (BMI 20 kg/m2), regardless of gonadal status and the secretagogue pair. In particular, the synergistic effects of GHRH and GHRP-2, L-arginine and GHRP-2, and L-arginine and GHRH failed to overcome putative somatostatinergic inhibition associated with increased BMI (2,19). The collective outcomes suggest that relative adiposity reduces GH secretion by an as yet undefined mechanism that at minimum: 1) does not involve isolated deficiency of endogenous GHRH or ghrelin/GHRP, and 2) cannot be reversed by GHRH/GHRP-2 or L-arginine stimulation. The last finding suggests that the negative effect of obesity may not involve excessive somatostatinergic inhibition, at least to the extent that L-arginine limits somatostatin outflow. Decreased somatostatin release and action are strongly inferred by the capability of L-arginine to antagonize GH autofeedback (34,35,43).

Caveats include the need to conduct similar studies in other age groups, and, to the degree practicable, after longer intervals and variable degrees of gonadal suppression. The gonadal down-regulation paradigm could be combined with transdermal supplementation of sex steroids, as performed recently in women (28,29), and evaluated in relation to other secretagogues of importance (2). A larger sample size might allow one to establish differences in dual secretagogue-stimulated GH secretion among varying subsets of lean, overweight, and obese eugonadal and hypogonadal subjects.

In summary, implementation of a gonadal down-regulation paradigm in young men disclosed that short-term (1 month) sex steroid withdrawal attenuates GHRH/GHRP-2 and L-arginine/GHRP-2 synergy in a BMI-dependent fashion. The extent to which earlier studies of hypogonadism were underpowered by not accounting for this tripartite relationship is not known.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kay Nevinger for support of manuscript preparation, Ashley Bryant for data analysis and graphics, the Mayo Immunochemical Laboratory for assay assistance, and the Mayo research nursing staff for implementing the protocol.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part via the Center for Translational Science Activities Grant 1 UL 1 RR024150 to the Mayo Clinic and Foundation from the National Center for Research Resources (Rockville, MD), and R01 NIA AG019695 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online December 11, 2007

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; CRU, Clinical-Translational Research Unit; CV, coefficient of variation; E2, estradiol; GHRP, GH-releasing peptide; IGFBP, IGF binding protein; NS, not significant; Te, testosterone.

References

- Weltman A, Weltman JY, Hartman ML, Abbott RD, Rogol AD, Evans WS, Veldhuis JD 1994 Relationship between age, percentage body fat, fitness, and 24-hour growth hormone release in healthy young adults: effects of gender. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78:543–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Roemmich JN, Richmond EJ, Bowers CY 2006 Somatotropic and gonadotropic axes linkages in infancy, childhood, and the puberty-adult transition. Endocr Rev 27:101–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Liem AY, South S, Weltman A, Weltman J, Clemmons DA, Abbott R, Mulligan T, Johnson ML, Pincus SM, Straume M, Iranmanesh A 1995 Differential impact of age, sex-steroid hormones, and obesity on basal versus pulsatile growth hormone secretion in men as assessed in an ultrasensitive chemiluminescence assay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:3209–3222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T, Berelowitz M, Joffe SN, Thorner MO, Rivier J, Vale WW, Frohman LA 1984 Impaired growth hormone responses to growth hormone-releasing factor in obesity. A pituitary defect reversed with weight reduction. N Engl J Med 311:1403–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahl N, Jorgensen JO, Jurik AG, Christiansen JS 1996 Abdominal adiposity and physical fitness are major determinants of the age-associated decline in stimulated GH secretion in healthy adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:2209–2215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneli G, Di Somma C, Baldelli R, Rovere S, Gasco V, Croce CG, Grottoli S, Maccario M, Colao A, Lombardi G, Ghigo E, Camanni F, Aimaretti G 2005 The cut-off limits of the GH response to GH-releasing hormone-arginine test related to body mass index. Eur J Endocrinol 153:257–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iranmanesh A, Lizarralde G, Veldhuis JD 1991 Age and relative adiposity are specific negative determinants of the frequency and amplitude of growth hormone (GH) secretory bursts and the half-life of endogenous GH in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 73:1081–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo KE, Miller T, DeAlmeida V, Godfrey P, Zheng J, Cunha SR 2000 Regulation of the pituitary somatotroph cell by GHRH and its receptor. Recent Prog Horm Res 55:237–266 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuto Y, Shibasaki T, Otagiri A, Kuriyama H, Ohata H, Tamura H, Kamegai J, Sugihara H, Oikawa S, Wakabayashi I 2002 Hypothalamic growth hormone secretagogue receptor regulates growth hormone secretion, feeding, and adiposity. J Clin Invest 109:1429–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low MJ, Otero-Corchon V, Parlow AF, Ramirez JL, Kumar U, Patel YC, Rubinstein M 2001 Somatostatin is required for masculinization of growth hormone-regulated hepatic gene expression but not of somatic growth. J Clin Invest 107:1571–1580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantel J, Legendre M, Cabrol S, Hilal L, Hajaji Y, Morisset S, Nivot S, Vie-Luton MP, Grouselle D, de Kerdanet M, Kadiri A, Epelbaum J, Le Bouc Y, Amselem S 2006 Loss of constitutive activity of the growth hormone secretagogue receptor in familial short stature. J Clin Invest 116:760–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iranmanesh A, Bowers CY, Veldhuis JD 2004 Activation of somatostatin-receptor subtype-2/-5 suppresses the mass, frequency, and irregularity of growth hormone (GH)-releasing peptide-2-stimulated GH secretion in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:4581–4587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhy LS, Veldhuis JD 2005 Deterministic construct of amplifying actions of ghrelin on pulsatile growth hormone secretion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288:R1649–R1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers CY, Granda-Ayala R 1996 GHRP-2, GHRH and SRIF interrelationships during chronic administration of GHRP-2 to humans. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 9(Suppl 3):261–270 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhy LS, Bowers CY, Veldhuis JD 2007 Model-projected mechanistic bases for sex differences in growth-hormone regulation in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292:R1577–R1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs CJ, Plymate SR, Rosen CJ, Adler RA 1993 Testosterone administration increases insulin-like growth factor-I levels in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 77:776–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giustina A, Scalvini T, Tassi C, Desenzani P, Poiesi C, Wehrenberg WB, Rogol A, Veldhuis JD 1997 Maturation of the regulation of growth hormone secretion in young males with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism pharmacologically exposed to progressive increments in serum testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:1210–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentili A, Mulligan T, Godschalk M, Clore J, Patrie J, Iranmanesh A, Veldhuis JD 2002 Unequal impact of short-term testosterone repletion on the somatotropic axis of young and older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:825–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giustina A, Veldhuis JD 1998 Pathophysiology of the neuroregulation of growth hormone secretion in experimental animals and the human. Endocr Rev 19:717–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Roemmich JN, Richmond EJ, Rogol AD, Lovejoy JC, Sheffield-Moore M, Mauras N, Bowers CY 2005 Endocrine control of body composition in infancy, childhood and puberty. Endocr Rev 26:114–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iranmanesh A, South S, Liem AY, Clemmons D, Thorner MO, Weltman A, Veldhuis JD 1998 Unequal impact of age, percentage body fat, and serum testosterone concentrations on the somatotrophic, IGF-I, and IGF-binding protein responses to a three-day intravenous growth hormone-releasing hormone pulsatile infusion in men. Eur J Endocrinol 139:59–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berghe G, de Zegher F, Bouillon R 1998 Acute and prolonged critical illness as different neuroendocrine paradigms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:1827–1834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel AV, Peake GT, Rada RT 1985 Pituitary-testicular axis dysfunction in burned men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 60:658–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Chan V, Yeung RTT 1978 Effect of surgical stress on pituitary-testicular function. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 9:255–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PY, Iranmanesh A, Nehra AX, Keenan DM, Veldhuis JD 2005 Mechanisms of hypoandrogenemia in healthy aging men. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 34:935–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Iranmanesh A, Keenan DM 2004 An ensemble perspective of aging-related hypoandrogenemia in men. In: Winters SJ, ed. Male hypogonadism: basic, clinical, and theoretical principles. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 261–284 [Google Scholar]

- Fryburg DA, Weltman A, Jahn LA, Weltman JY, Samolijik E, Veldhuis JD 1997 Short-term modulation of the androgen milieu alters pulsatile, but not exercise- or growth hormone (GH)-releasing hormone-stimulated GH secretion in healthy men: impact of gonadal steroid and GH secretory changes on metabolic outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:3710–3719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson D, Keenan DM, Mielke K, Bradford K, Bowers CY, Miles JM, Veldhuis JD 2004 Dual secretagogue drive of burst-like growth hormone secretion in postmenopausal compared with premenopausal women studied under an experimental estradiol clamp. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:4746–4754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson D, Keenan DM, Farhy LS, Mielke K, Bowers CY, Veldhuis JD 2005 Determinants of dual secretagogue drive of burst-like growth hormone secretion in premenopausal women studied under a selective estradiol clamp. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:1741–1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berghe G 2000 Novel insights into the neuroendocrinology of critical illness. Eur J Endocrinol 143:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SM, Shah N, Evans WS, Patrie JT, Bowers CY, Veldhuis JD 2001 Short-term estradiol supplementation augments growth hormone (GH) secretory responsiveness to dose-varying GH-releasing peptide infusions in healthy postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:551–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Evans WS, Bowers CY 2002 Impact of estradiol supplementation on dual peptidyl drive of growth-hormone secretion in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:859–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Evans WS, Bowers CY 2003 Estradiol supplementation enhances submaximal feedforward drive of growth hormone (GH) secretion by recombinant human GH-releasing hormone-1,44-amide in a putatively somatostatin-withdrawn milieu. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:5484–5489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghigo E, Arvat E, Valente F 1991 Arginine reinstates the somatotrope responsiveness to intermittent growth hormone-releasing hormone administration in normal adults. Neuroendocrinology 54:291–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alba-Roth J, Muller OA, Schopohl J, Von Werder K 1988 Arginine stimulates growth hormone secretion by suppressing endogenous somatostatin secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 67:1186–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SM, Wideman L, Patrie JT, Weltman A, Bowers CY, Veldhuis JD 2001 E2 supplementation selectively relieves GH’s autonegative feedback on GH-releasing peptide-2-stimulated GH secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:5904–5911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LD, van Belle G 1996 Descriptive statistics. In: Biostatistics: a methodology for the health sciences. New York: John Wiley, Sons; 58–74 [Google Scholar]

- Link K, Blizzard RM, Evans WS, Kaiser DL, Parker MW, Rogol AD 1986 The effect of androgens on the pulsatile release and the twenty-four hour mean concentrations of growth hormone in peripubertal males. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 62:159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondanelli M, Ambrosio MR, Margutti A, Franceschetti P, Zatelli MC, degli Uberti EC 2003 Activation of the somatotropic axis by testosterone in adult men: evidence for a role of hypothalamic growth hormone-releasing hormone. Neuroendocrinology 77:380–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Merriam GR, Sherins RJ 1987 Chronic sex steroid exposure increases mean plasma growth hormone concentration and pulse amplitude in men with isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 64:651–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Keenan DM, Mielke K, Miles JM, Bowers CY 2005 Testosterone supplementation in healthy older men drives GH and IGF-I secretion without potentiating peptidyl secretagogue efficacy. Eur J Endocrinol 153:577–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers CY, Chang JK, Wu S, Linse KD, Hurley DL, Veldhuis JD 2006 Biochemistry of the growth hormone-releasing peptides, secretagogues and ghrelin. In: Mantovani G, Anker SD, Inui A, Morley JE, Fanelli F, Scevola D, Schuster M, Yeh SS, eds. Cachexia and wasting: a modern approach. New York: Springer; 219–234 [Google Scholar]

- Chihara K, Minamitani N, Kaji H, Arimura A, Fujita T 1981 Intraventricularly injected growth hormone stimulates somatostatin release into rat hypophysial portal blood. Endocrinology 109:2279–2281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]