Abstract

Context: Human β-cell gene profiling is a powerful tool for understanding β-cell biology in normal and pathological conditions. Assessment is complicated when isolated islets are studied because of contamination by non-β-cells and the trauma of the isolation procedure.

Objective: The objective was to use laser capture microdissection (LCM) of human β-cells from pancreases of cadaver donors and compare their gene expression with that of handpicked isolated islets.

Design: Endogenous autofluorescence of β-cells facilitated procurement of purified β-cell tissue from frozen pancreatic sections with LCM. Gene expression profiles of three microdissected β-cell samples and three isolated islet preparations were obtained. The array data were normalized using DNA-Chip Analyzer software (Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA), and the lower confidence bound evaluated differentially expressed genes. Real-time PCR was performed on selected acinar genes and on the duct cell markers, carbonic anhydrase II and keratin 19.

Results: Endogenous autofluorescence facilitates the microdissection of β-cell rich tissue in human pancreas. When compared with array profiles of purified β-cell tissue, with lower confidence bound set at 1.2, there were 4560 genes up-regulated and 1226 genes down-regulated in the isolated islets. Among the genes up-regulated in isolated islets were pancreatic acinar and duct genes, chemokine genes, and genes associated with hypoxia, apoptosis, and stress. Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed the differential expression of acinar gene transcripts and the duct marker carbonic anhydrase II in isolated islets.

Conclusion: LCM makes it possible to obtain β-cell enriched tissue from human pancreas sections without the trauma and ischemia of islet isolation.

This study finds laser capture microdissection an effective way to obtain and analyze β-cell enriched preparations from the human pancreas without contamination by non-β-cells and the trauma and ischemia of islet isolation.

Pancreatic β-cell phenotype is maintained by the expression of a unique set of genes and the suppression of others (1,2). Gene expression profiles provide new insights into the β-cell biology of normal and pathological conditions. Currently, data are available from studies on the cell line MIN-6 (3) and rat β-cells purified with flow cytometry (2). In humans, data have been obtained on islets isolated from organ donors using gene arrays and proteomics (4,5,6,7). A weakness in using isolated islets is the duration and traumatic nature of isolation that cause changes in gene expression (8,9); moreover, islet preparations are inevitably contaminated with exocrine tissue (6,10). These limitations can be overcome by dissecting β-cells from pancreas directly using laser capture microdissection (LCM), which allows sampling of groups of cells that can be analyzed for gene or protein expression (11). The technique has been applied to rodent islets, allowing the dissection of β-cell rich cores from frozen pancreatic sections (12,13,14,15).

The use of LCM is complicated by the complex anatomy of human islets. Unlike rodent islets with a central core of β-cells surrounded by a mantle of non-β-cells, human islets consist of multiple subunits with β-cells clumped together, each with their individual mantles. Thus, non-β-cells can be in the middle of some islets. In the present study, a protocol was developed that took advantage of intrinsic autofluorescence of β-cells to allow LCM of purified β-cell tissue from pancreases of cadaver donors. Gene expression of these cells was then compared with that from handpicked isolated islets. It was predicted that these highly purified isolated islets would be contaminated with exocrine cells, and have increased expression of genes associated with hypoxia, stress, and apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Tissue samples and islet isolation

Pancreases from the New England Organ Bank were processed in the Joslin Islet Cell Resource Center. Pieces of pancreas from three different donors were excised, placed in cryomolds, embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT (Sakura Finetek U.S.A., Inc., Torrance, CA), frozen in chilled isopentane, and stored at −80 C, pending sectioning at 8 μm. From remaining pancreas, islets were isolated using standard techniques (16). The final purity of the islets was determined by hematoxylin staining of 1-μm plastic sections of the islet preparations. The three preparations of isolated islets were initially 75, 85, and 50% pure. Islet viability, determined by fluorescein diacetate and propidium iodide, for the three islet preparations was 85, 90, and 95%, respectively. Of the samples used, two were from the same pancreases as the frozen samples, and one was from a different donor.

The human islets were cultured for 12 h at 37 C in Final Wash Solution (Mediatech 99–785-CV; Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA) supplemented with 2.5% (wt/vol) human serum albumin. Islets were handpicked to obtain purity as close to 100% as possible. Groups of about 3000 islets were used for RNA extraction.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunostaining of insulin and glucagon, frozen sections were fixed by immersion in 4% buffered formaldehyde for 20 min and rinsed twice in PBS. Nonspecific antibody binding was blocked with 2% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 C with guinea pig antiinsulin antibody (1:200; LINCO Research, Inc., St. Charles, MO) or guinea pig antiglucagon antibody (1:3000; LINCO). After rinsing sections twice in PBS, direct staining was performed by incubation with Texas Red-conjugated donkey antiguinea pig IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 1 h. Sections were then rinsed twice in PBS and mounted with 1,4-diazabicyclo(2.2.2)octane glycerol antifading medium.

Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 410 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY) using excitation wavelengths of 488 nm for green fluorescence (autofluorescence) and 568 nm for red fluorescence (immunofluorescence).

LCM

Immediately before LCM, frozen pancreatic sections were dehydrated in 70% ethanol for 30 sec, 100% ethanol twice for 1 min, and xylene for 4 min. The sections were air dried, and LCM was performed using PixCell II Laser Capture Microdissection System (Arcturus Engineering, Mountain View, CA). LCM was performed by melting thermoplastic films mounted on transparent LCM caps (Arcturus) on selected populations of cells with autofluorescence. For the smallest spot size, the system was set to the following parameters: 35 mW for the laser power, 4.5 msec pulse duration, and 7.5 μm spot size. The thermoplastic film containing the microdissected cells was incubated with 10 μl of a guanidine thiocyanate and polyethylene glycol octylphenol ether-based buffer for 30 min at 42 C. Each microdissection session was performed in less than 30 min, during which no more than four sections were processed; each section typically contained three to seven islets. For each islet there may be two to four clumps of bright cells resulting in about 20–50 pulses per islet, or about 200–250 pulses per section. Thus, 20 sections were used to obtain at least 5000 pulses that are needed to obtain sufficient RNA for arrays.

RNA extraction, amplification, and biotinylation

Total RNA was extracted from isolated islets using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), followed by RNA cleanup using QIAGEN RNAeasy kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and treatment with DNase I for 15 min at RT (RNase Free DNase Set; QIAGEN). RNA quantity and purity were evaluated spectrophotometrically by readings at 260 nm (A260) and 280 nm (A280). RNA integrity was assessed running 3 μg sample in 1% agarose gel. Total RNA was extracted from captured cells using PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit (Arcturus). Genomic DNA was removed by incubation with DNase I for 15 min at RT (QIAGEN).

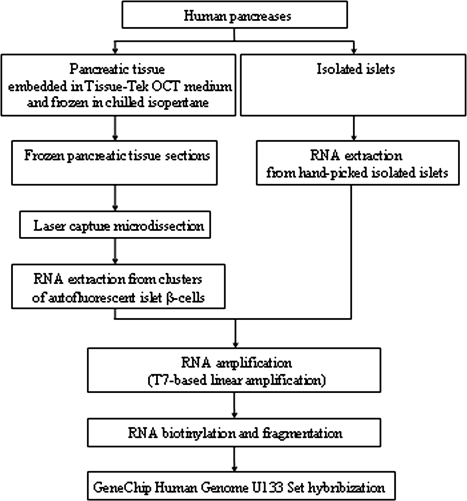

The RNA from the laser-captured cells and isolated islets was amplified by T7-based amplification using T7-oligo-dT-primers. Two rounds of amplification were performed using RiboAmp HS RNA Amplification Kits (Arcturus) to standardize the protocol for both isolated islets and laser-captured cells (17). Amplified RNA (aRNA) quantity was determined by absorbance at 260 and 280 nm, and the quality of RNA was assessed on 1% agarose gel. aRNA (1.5 μg) obtained from each sample was converted into double-stranded cDNA using the RiboAmp HS RNA Amplification Kit. Biotinylated cRNA was generated from cDNA by in vitro transcription reaction using the BioArray High Yield RNA Transcript Labeling Kit (Enzo Diagnostics, Farmingdale, NY). RNA products were purified using the MiraCol Purification Columns (Arcturus). A flow chart of the approach is contained in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the experimental design and the procedures used.

Microarray analysis

Biotinylated cRNA was fragmented to nucleotide stretches of 30–200 nucleotides and hybridized to the GeneChip Human Genome U133 Set (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The chips contain more than 45,000 probe sets representing 39,000 transcript variants, of which more than 33,000 are well-characterized human genes. Array data were normalized and analyzed using the DNA-Chip Analyzer software (Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA), which normalizes data of multiple arrays to a common baseline array having the median overall brightness (18). Thus, it is possible to assess ses for expression indexes and to calculate confidence intervals for fold changes (19). A lower confidence bound (LCB) cutoff of 1.2 was used to assess differentially expressed genes.

Genes were classified on functional clusters identified on the Gene Ontology web site (http://www.geneontology.org) (20), and pathway analysis was performed using Ingenuity Software Knowledge Base (Redwood City, CA).

Principal components analysis (PCA)

PCA projects high-dimensional data into lower dimensions, and calculates the proportion of variation in the data by determining the first principal component and the second principal component (21). Samples were projected into a two-dimensional space; each dimension was normalized to mean zero and sd one.

Determination of β-cell enrichment by LCM and real-time PCR

To evaluate β-cell enrichment in laser-captured β-cell samples, insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin transcripts were quantified by real-time PCR. Comparison was made between samples obtained by LCM of clumps of autofluorescent cells vs. LCM of islet tissue purposely ignoring the autofluorescence to ensure that all islet cell types would be collected. To avoid artifact from amplification, enough tissue was dissected so that RNA did not need to be amplified before PCR analysis. Each specimen was obtained from not less than 7000 hits. Two sets of experiments were performed: with one pancreas, two β-cell samples were compared with one islet sample; with another organ, one β-cell sample was compared with one islet sample. In total three comparisons were performed using pancreas from two different donors. Total RNA was extracted as previously described. RNA quantity and purity were evaluated by absorbance readings at 260 and 280 nm using the NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). cDNA templates were synthesized from 35.5 ng total RNA using TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was used to perform real-time PCR in the presence of 0.3 ng cDNA, 1 μm primers, and 0.25 μm probe in a total volume of 20 μl. The housekeeping gene ribosomal protein S18 (RPS18) transcript was used as a reference. Primers and probes were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems) and were purchased from MWG-Biotech Inc. (MWG-Biotech Inc., High Point, NC), except for RPS18, which was obtained from Assay on Demand (Applied Biosystems). Primers and probe sequences except for RPS18 are reported in Table 1. The expression of each transcript was evaluated in triplicate. ΔCycle Threshold (CT) values of glucagon or somatostatin in the β-cell samples were used to calculate the differences between glucagon or somatostatin and insulin gene expression in β-cell or islet samples using the ΔΔCT method. The fold changes obtained were used to calculate ratios of expression of glucagon or somatostatin to insulin in β-cell enriched and islet samples.

Table 1.

Primer set and probe for the real-time PCR analysis of islet hormones and acinar transcripts

| cDNA | GenBank accession no. | Primer | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Probe sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INS | NM_000207 | F | GCAGCCTTTGTGAACCAACA | TGCGGCTCACACCTGGTGGAAG |

| R | TTCCCCGCACACTAGGTAGAGA | |||

| GCG | NM_002054 | F | CAAGGCAGCTGGCAACGT | CAGGCAGACCCACTCAGTGATCCTGAT |

| R | CTGGTGAATGTGCCCTGTGA | |||

| SST | NM_001048 | F | GATGCCCTGGAACCTGAAGA | CTGTCCCAGGCTGCTGAGCAGGA |

| R | CTGCAGCTCAAGCCTCATTTC | |||

| AMY2A | NM_000699 | F | ACTGGACATTTTCTTTAACTTTGCAA | TGGTCTTCCTGCTGGCACATACTGTGA |

| R | GCCATTAATTTTATCTCCAGAAATGAC | |||

| PRSS1 | NM_002769 | F | CATGTTCTGTGTGGGCTTCCT | AGGGAGGCAAGGATTCATGTCAGGGT |

| R | ACCACAGGGCCACCAGAAT | |||

| PRSS2 | NM_002770 | F | TCCTGCCAGGGTGATTCTG | TGGCCCTGTGGTCTCCAATGGAGA |

| R | ATAGCCCCAGGAGACAATTCC | |||

| ELA3A | NM_005747 | F | TGCCCCACAGAGGATGGT | AGCTTTGTTTCTGGCTTTGGCTGCAAC |

| R | CCGTGGGCTTCCAGATGA | |||

| CPA2 | NM_001869 | F | GCCAGCCCGTCAGATCCT | CCCACAGCCGAGGAGACCTGGC |

| R | ATGCTCCATGATTGCCTTCAA | |||

| CPB1 | NM_001871 | F | TCACTGCACGGCACCAAGT | CACATATGGCCCGGGAGCTACAACA |

| R | CCCCCAGCAGCAGGATAGA | |||

| PNLIP | NM_000936 | F | AGATTATAGTGGAGACAAATGTTGGAAA | CAGTTCAACTTCTGTAGTCCAGAAACCGTCAGG |

| R | GTGAGGGTGAGCAGAACTTCCT | |||

| CA2 | NM_000067 | F | ACAATTGTTGACTAAAATGCTGCTTT | TGGTTGAGTGCAAATCCATAGCACAAGATAAA |

| R | CTATTTTACCTGATTTGCCTTAACTAGCT | |||

| CK19 | NM_002276 | F | GAGTACCAGCGGCTCATGGA | CAAGTCGCGGCTGGAGCAGGA |

| R | GCTGCGGTAGGTGGCAAT | |||

| RPL32 | NM_000994 | F | CTGGCCATCAGAGTCACCAA | CCCAATGCCAGGCTGCGCA |

| R | TGAGCTGCCTACTCATTTTCTTCA |

Oligonucleotide sequences for forward (F) and reverse (R) primers are shown. RPL32, Ribosomal protein L32.

Determination of acinar and duct cell contamination by real-time PCR

PCR measurements of selected acinar transcripts and duct marker genes, carbonic anhydrase II (CA2) and keratin 19 (CK19), were determined. cDNA templates were synthesized from 1 μg aRNA using TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents. TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix was used to perform real-time PCR in the presence of 0.2 ng cDNA, 1 μm primers, and 0.25 μm probe in a total volume of 20 μl. The housekeeping gene ribosomal protein L32 transcript was used as a reference. For each sample, triplicate amplifications were performed, and average measurements were taken for data analysis. The N-fold differential expression was expressed as 2−ΔΔCT.

Statistical analysis

Correlation among samples was assessed using the Pearson’s correlation test. Comparisons between groups were performed by the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Statistical analysis of the pathways was performed using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

β-Cell autofluorescence

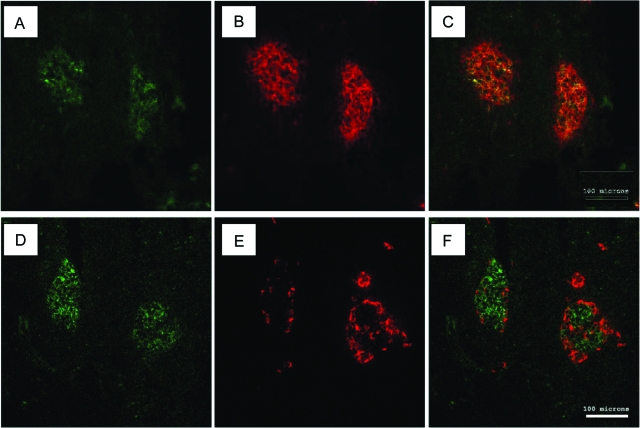

Autofluorescence of frozen pancreatic sections (Fig. 2, A and D) corresponds to β-cells as determined by insulin immunostaining (Fig. 2, B and C). In contrast, glucagon staining shows that α-cells form a mantle around the autofluorescent areas (Fig. 2, E and F).

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescent staining and autofluorescent signal of frozen pancreatic tissue. Insulin or glucagon antibody localization showed by Texas Red (red) and β-cell autofluorescent signal showed by green fluorescence. A and D, Autofluorescent signal in pancreatic islets. B, Pancreatic sections stained with insulin antibody. E, Pancreatic sections stained with glucagon antibody. C, Insulin and autofluorescent signals are colocalized. F, Glucagon signal is distinct from that of autofluorescence. Bar, 100 μm.

Quantity and quality of RNA

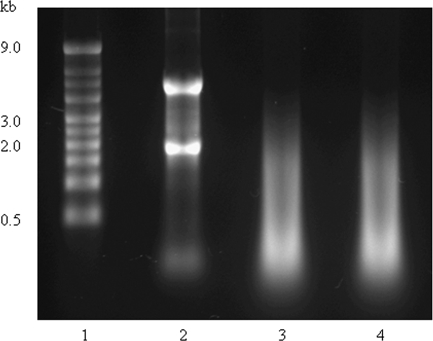

RNA extraction from handpicked isolated islets yielded 5.7 ± 0.4 μg total RNA with A260:A280 ratio ranging between 1.7 and 1.9; the amplification of 200 ng total RNA yielded 82.0 ± 25.8 μg aRNA with A260:A280 ratio between 2.1 and 2.2. RNA extraction and amplification from the laser-captured samples, obtained by microdissection of clusters of islet autofluorescent β-cells, yielded 34.3 ± 8.3 μg aRNA with A260:A280 ratio ranging from 2.4–2.6. The A260:A280 ratio of the aRNA was within the acceptable limits. The integrity of the RNA extracted from the isolated islets and the quality of the RNA amplified from the isolated islets and the laser-captured samples were evaluated by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3). The RNA extracted from the isolated islets showed two clear bands, 18S and 28S. The aRNA from the isolated islets or from the laser-captured samples as expected appeared as a smear ranging from 200-2000 bases in length (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Agarose electrophoresis of total and aRNA. Gel electrophoresis was performed to evaluate the integrity of total RNA extracted from isolated islets and the quality of RNA amplified from isolated islets and laser-captured β-cell samples. Total RNA from handpicked isolated islets shows two bands, corresponding to 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA (lane 2). aRNA from isolated islets (lane 3) and microdissected β-cells (lane 4) appear as a smear ranging between 200 and 2000 bases in length. Lane 1, RNA marker.

β-Cell enrichment in laser-captured β-cell samples

LCM samples were obtained from selected β-cell rich autofluorescent areas of islets or from generalized nonselected areas of islet tissue. Real-time PCR was performed on unamplified RNA to avoid artifacts from amplification. For the generalized nonselected LCM of islet tissue, the glucagon signal was 16.7% of the insulin signal (16.7% was found in two separate pancreases), whereas for the β-cell selected tissue, the percentages were 2.6 and 3.9% from two separate dissections of one pancreas and 2.2% from the other. With somatostatin, for the nonselected tissue, the signal was 13 and 16.7% of insulin in two separate pancreases. For the β-cell selected tissue, somatostatin was 5.5 and 4.1% of insulin in two separate dissections from one pancreas and 5.3% in the other pancreas.

Expression profiles in the isolated islets compared with the laser-captured cells

The number of genes differentially expressed depended on the LCB cutoff used. With the LCB set at two, there were 2351 genes up-regulated and 230 genes down-regulated in the isolated islets. When the LCB was changed to 1.2, the number of up-regulated genes in the isolated islets increased to 4560 and that of the down-regulated genes was 1226. Only those genes reliably overexpressed with present detection calls in at least two data sets were considered among those differentially expressed. Differentially expressed genes were categorized into top-level classes defined for their functions by the Gene Ontology Consortium (20). Within the differentially expressed genes, 3360 up-regulated and 892 down-regulated islet transcripts were defined by molecular functions and/or biological processes; among them, the largest classes were those coding proteins with binding activity, transcription regulator activity, enzyme and enzyme regulator activity (Table 2). The microarray data are available at http://www.joslinresearch.org/weirg_etal.

Table 2.

Molecular function or biological process classes of the genes differentially expressed in isolated islets

| Molecular or biological functions | No. of up-regulated genes (%) | No. of down-regulated genes (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Binding activity | 1161 (36) | 299 (33) |

| Transporter activity | 336 (10) | 88 (10) |

| Transcription regulator activity | 421 (13) | 123 (14) |

| Translation regulator activity | 99 (3) | 10 (1) |

| Signal transducer activity | 164 (5) | 68 (8) |

| Structural molecule activity | 78 (2) | 20 (2) |

| Enzyme and enzyme regulator activity | 449 (13) | 132 (15) |

| Catalytic activity | 102 (3) | 17 (2) |

| Receptor activity | 79 (2) | 22 (2) |

| Cell adhesion molecule activity | 49 (1) | 16 (2) |

| Inflammatory, immune, defense response genes | 47 (1) | 16 (2) |

| Apoptosis | 48 (1) | 10 (1) |

| Protein metabolism | 327 (10) | 71 (8) |

The number and percentage of differentially expressed transcripts within each functional class are reported.

Sample analysis

Correlation coefficients within groups were 0.96 ± 0.02 and 0.97 ± 0.01 for laser-captured β-cell samples and islet samples, respectively; correlation across samples in the two groups was 0.88 ± 0.02. PCA resulted in first principal component and second principal component explaining 88.3 and 7.2% proportion of variation, showing clear separation between laser-captured β-cell and islet samples.

Contamination of isolated islets with pancreatic exocrine cells

Acinar genes, except for CTRB1 and CPA1, were more expressed in isolated islets than in β-cell samples. The LCB values obtained from the array data analysis ranged between 1.4 (CTRC) and 17.3 (AMY2A) (supplemental Table 1, which is published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://jcem.endojournals.org), indicating a wide variation of the differential expression. The expression levels of AMY2A, PRSS1, PRSS2, ELA3A, CPA2, CPB1, and PNLIP were quantified by real-time PCR, and were significantly up-regulated in isolated islets (Table 3).

Table 3.

N-fold differential expression of acinar and duct cell transcripts between isolated islets and β-cell samples

| Gene symbol | N-fold differential expression

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean isolated islet samples ± se | Mean β-cell samples ± se | ||

| AMY2A | 305.6 ± 128.7 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.003 |

| PRSS1 | 67.0 ± 26.5 | 3.2 ± 1.8 | 0.013 |

| PRSS2 | 59.8 ± 19.5 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 0.004 |

| ELA3A | 82.8 ± 20.5 | 6.6 ± 4.3 | 0.049 |

| CPA2 | 53.5 ± 20.1 | 3.8 ± 1.7 | 0.020 |

| CPB1 | 1321.8 ± 545.7 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 0.001 |

| PNLIP | 101.1 ± 43.5 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 0.005 |

| CA2 | 16.2 ± 2.3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.013 |

| CK19 | 27.0 ± 12.0 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 0.089 |

See text in Materials and Methods for details.

For the duct cell markers, CA2 and CK19, the differences in expression signals in isolated islets compared with β-cell enriched samples were not significant in the arrays. However, by real-time PCR, CA2 in isolated islets was increased; trend to higher CK19 expression missed statistical significance.

Expression of proinflammatory genes in isolated islets

Chemokine genes were up-regulated in isolated islet samples. The C-X-C chemokine genes were the most abundant: they comprised IL-8, GRO1, GRO2, GRO3, and IP9. MIP3A was the only C-C chemokine differentially expressed (supplemental Table 1).

Increased expression of hypoxia induced and oxidative stress genes in isolated islets

HIF1A and HIF1B, the latter also known as hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), were up-regulated in isolated islet samples. These genes code the subunits HIF1α and HIF1β, which interact to form the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), a transcription factor implicated in the transcriptional activation of genes in hypoxic cells. Genes regulated by HIF-1, such as glucose transporter 3, HK2, PGK1, and lactate dehydrogenase A, were differentially expressed (supplemental Table 1). Other overexpressed genes modulated by HIF-1 were P4HA1, which encodes an enzyme involved in collagen synthesis, and BNIP3, a member of Bcl-2 proapoptotic family genes. EDN-1 and ADM, which code for proteins affecting insulin release in rodent islets (22,23), and TFRC, involved in iron uptake, were also overexpressed. In addition, some oxidative stress genes were up-regulated: CAT, MGST1, and most notably SOD2, which showed an LCB of 9.8.

Expression of apoptosis-associated genes in isolated islets

Isolated islets showed higher expression of genes related to apoptosis (supplemental Table 1). They were pro- and antiapoptotic genes belonging to the extrinsic pathways: mainly the TNF-mediated pathway; the intrinsic pathways, mitochondria-mediated and p53-dependent; or common to the three pathways. In particular, genes involved in the TNF pathway were TNFRSF10B and TNFRSF19, coding for receptor proteins, and TRAF3, which is involved in signal transduction. Also found were TNFAIP3 (A20) and TNFAIP8, which code proteins with antiapoptotic activity. Other up-regulated genes with antiapoptotic function were BIRC2, BIRC3, and BIRC4.

Genes of the mitochondria-mediated apoptotic pathway, which were up-regulated, included genes directly or indirectly involved in the regulation of the mitochondrial membrane permeability. These include those with either pro-apoptotic function, such as BID, IFT57, BNIP3, BNIP3L, and MOAP1, or antiapoptotic effects, such as BCL2 and TEGT. BNIP2, which acts as BNIP3, was also overexpressed. The other up-regulated mitochondria-pathway associated genes are reported in supplemental Table 1.

A few genes of the p53-dependent pathway (TP53BP2, TP53INP1, and HIPK2) were also overexpressed in isolated islet samples.

Expression of MAPK and other stress-associated genes in isolated islets

MAPK genes, SERP1, and molecular chaperones were up-regulated in isolated islet samples (supplemental Table 1). MAPKs are components of three kinase pathways: the ERKs pathway, activated by growth factors; the Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) and the p38 MAPKs, activated in response to stressful conditions. Among these three pathways, some of the overexpressed genes belonged to the ERK pathway (MAPK1, MAPK6, MAP2K1, MAP2K1IP1, and MAP3K8), many were genes of the JNK pathway (MAPK9, MAP2K4, MAP3K2, MAP3K5, MAP4K3, MAP4K4, and MAP4K5), and only two genes belonged to the p38 MAPKs pathway (MAP2K3 and MAP3K7IP2) (supplemental Table 1).

SERP1, which is induced by stress, causing the accumulation of unfolded proteins in endoplasmic reticulum, was also overexpressed. Finally, many of the molecular chaperone genes, belonging to the chaperonin and chaperone families, were overexpressed. In physiological conditions chaperonins and chaperones assist the folding of newly synthesized proteins; under stress conditions they act by retaining misfolded proteins.

Pathway analysis

Pathways activated in isolated islets include those concerned with hypoxia (P = 1.26-13), apoptosis (0.00012), ERK/MAPK (1.26-12), p38 MAPK (0.000112), and the death receptor signaling pathway (0.005754). Graphical presentations are reported in supplemental Figs. 1–5, which are published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://jcem.endojournals.org.

Discussion

Our finding that human β-cells have endogenous autofluorescence allows dissection of β-cell rich tissue using LCM. The origin of autofluorescence is unknown, but possible contributors include aromatic amino acids, pyridinic and flavin coenzymes, porphyrins, and lipopigments (24,25,26,27). Interestingly, autofluorescence seems less intense in pancreases from younger cadaver donors. Purification of β-cell tissue by LCM was confirmed by the relative expression of glucagon or somatostatin to insulin as determined by real-time PCR on unamplified RNA. It is not surprising that there was some contamination from islet non-β-cells and even some exocrine cells that may have been nonspecifically transferred to the cap surface (28). Nonetheless, the ability to obtain purified β-cell tissue directly from pancreases provides a major advantage over the study of artifact-ridden isolated islets.

Differential expression of many genes between the LCM purified β-cell tissue from pancreas and isolated islets was predictable. Isolated islets are removed from their rich blood supply and dependent upon oxygen diffusion from the media, which means that many cells will be hypoxic. Thus, there will be differential expression of genes from contaminating cells and genes that are induced by hypoxia apoptosis, and isolation stress.

The stress of islet isolation induces the expression of pro-inflammatory genes (29,30) and their gene products (8,30). Our data are in agreement with previous studies for the expression of IL-8 and GRO2 (8,29), but we did not observe differential expression of IL-1β and IL6 (8,29) or of the C-C chemokine MCP1 (29,30). In contrast, chemokines not previously investigated in isolated islets were found expressed, including C-X-C chemokines GRO1, GRO3, IP9, and a C-C chemokine, MIP3A. For IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP1, the discrepancies between our data and what was previously described might be related to the different times at which the studies were performed or, for MCP1, to the constitutive expression of the chemokine in β-cells (30). Previous studies evaluated the gene expression in islets cultured for periods of 2–11 d (8,29).

Hypoxia and oxidative stress related to the isolation procedure (31) induced genes that can promote survival and reestablish cell homeostasis. In particular, overexpression of glucose transporter 3, genes of the glycolytic pathway, and lactate dehydrogenase A indicate that islet cells adapt to the hypoxic condition by enhancing anaerobic metabolism. Changes in islet cell metabolism may modify physiological insulin release, to which EDN1 and ADM may contribute (22,23). Hypoxia activates oxidative stress, and islet expression of CAT, MGST1, and SOD2 may counteract this insult.

Along with β-cell death induced by isolation (32), a variety of pro- and antiapoptotic genes were up-regulated, including those of both the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. These are accompanied by the up-regulation of the TNF pathway. Vulnerability to intracellular stimuli such as hypoxia and oxidative stress is indicated by overexpression of mitochondrial pathway genes (33,34,35).

Although JNK and p38 MAPKs pathways are thought to be activated in islets during isolation (9), it is unclear whether overexpression of MAPK genes results from stress of isolation, or from contaminating acinar cells. The same issue concerns the chaperonin and chaperone genes, and SERP1, which, in agreement with other studies (6,7,36), were found in isolated islets. They might be from acinar tissue, which expresses chaperones (37).

In conclusion, this study describes a novel procedure to obtain and analyze β-cell enriched preparations from the human pancreas. We propose that LCM of β-cells from the native pancreas is an important advance for the study of human β-cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Lock and Christopher Cahill for valuable technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (National Center for Research Resources ICR U4Z RR 16606 and U19DK6125), the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, and the Diabetes Research and Wellness Foundation. Help was provided by the Advanced Microscopy and Genomics Cores of the Joslin Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center supported by the National Institutes of Health (DK36836).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online December 11, 2007

Abbreviations: aRNA, Amplified RNA; CA2, carbonic anhydrase II; CK19, keratin 19; CT, cycle threshold; HIF-1, hypoxia-inducible factor-1; JNK, Jun N-terminal kinases; LCB, lower confidence bound; LCM, laser capture microdissection; PCA, principal components analysis; RPS18, ribosomal protein S18.

References

- Sander M, German MS 1997 The β cell transcription factors and development of the pancreas. J Mol Med 75:327–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuit F, Flamez D, De Vos A, Pipeleers D 2002 Glucose-regulated gene expression maintaining the glucose-responsive state of β-cells. Diabetes 51(Suppl 3):S326–S332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb GC, Akbar MS, Zhao C, Steiner FD 2000 Expression profiling of pancreatic β cells: glucose regulation of secretory and metabolic pathway genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:5773–5778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev A, Pise-Masison CA, Radonovich M, Hoffmann SC, Hirshberg B, Brady JN, Harlan DM 2002 Oligonucleotide microarray analysis of intact human pancreatic islets: identification of glucose-responsive genes and a highly regulated TGFβ signaling pathway. Endocrinology 143:3695–3698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui H, Wang C, Li H, Bulotta A, D’Amico E, Khoury N, Nguyen E, Di Mario U, Chen IY, Perfetti R 2004 Gene expression profiling of cultured human islet preparations. Diabetes Technol Ther 6:481–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cras-Méneur C, Inoue H, Zhou Y, Ohsugi M, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Pape D, Clifton SW, Permutt MA 2004 An expression profile of human pancreatic islet mRNAs by Serial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE). Diabetologia 47:284–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M, Forsberg J, Bergsten P 2005 Protein profiling of human pancreatic islets by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res 4:931–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottino R, Balamurugan AN, Tse H, Thirunavukkarasu C, Ge X, Profozich J, Milton M, Ziegenfuss A, Trucco M, Piganelli JD 2004 Response of human islets to isolation stress and the effect of antioxidant treatment. Diabetes 53:2559–2568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelli S, Ansite J, Roduit R, Borsello T, Matsumoto I, Sawada T, Allaman-Pillet N, Henry H, Beckmann JS, Hering BJ, Bonny C 2004 Intracellular stress signaling pathways activated during human islet preparation and following acute cytokine exposure. Diabetes 53:2815–2823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TC, Barshes NR, Brunicardi FC, Alejandro R, Ricordi C, Nguyen L, Goss JA 2004 Procurement of the human pancreas for pancreatic islet transplantation. Transplantation 78:481–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner RF, Emmert-Buck M, Cole K, Pohida T, Chuaqui R, Goldstein S, Liotta LA 1997 Laser capture microdissection: molecular analysis of tissue. Science 278:1481–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laybutt DR, Sharma A, Sgroi DC, Gaudet J, Bonner-Weir S, Weir GC 2002 Genetic regulation of metabolic pathways in β-cells disrupted by hyperglycemia. J Biol Chem 277:10912–10921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laybutt DR, Kaneto H, Hasenkamp W, Grey S, Jonas JC, Sgroi DC, Groff A, Ferran C, Bonner-Weir S, Sharma A, Weir GC 2002 Increased expression of antioxidant and antiapoptotic genes in islets that may contribute to β-cell survival during chronic hyperglycemia. Diabetes 51:413–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toschi E, Gaudet J, Sharma A, Weir G, Sgroi D, Bonner-Weir S 2003. Delineation of phenotypic differences between new and old β-cells. Diabetes 52(Suppl 1):363 (Abstract 1573-P) [Google Scholar]

- Ahn YB, Xu G, Marselli L, Toschi E, Sharma A, Bonner-Weir S, Sgroi DC, Weir GC 2007 Changes in gene expression in β cells after islet isolation and transplantation using laser-capture microdissection. Diabetologia 50:334–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linetsky E, Bottino R, Lehmann R, Alejandro R, Inverardi L, Ricordi C 1997 Improved human islet isolation using a new enzyme blend, liberase. Diabetes 46:1120–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XJ, Salunga R, Tuggle JT, Gaudet J, Enright E, McQuary P, Payette T, Pistone M, Stecker K, Zhang BM, Zhou YX, Varnholt H, Smith B, Gadd M, Chatfield E, Kessler J, Baer TM, Erlander MG, Sgroi DC 2003 Gene expression profiles of human breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:5974–5979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wong WH 2001 Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:31–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wong WH 2001 Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: model validation, design issues and standard error application. Genome Biol 2:RESEARCH0032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gene Ontology Consortium 2001 Creating the gene ontology resource: design and implementation. Genome Res 11:1425–1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgrebe J, Wurst W, Welzl G 2002 Permutation-validated principal components analysis of microarray data. Genome Biol 3:RESEARCH0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen S, Thomsen JL, Brock B, Hermansen K 1996 Endothelin-1 stimulates insulin secretion by direct action on the islets of Langerhans in mice. Diabetologia 39:1030–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A, Weaver C, Lopez J, Bhathena SJ, Elsasser TH, Miller MJ, Moody TW, Unsworth EJ, Cuttitta F 1996 Regulation of insulin secretion and blood glucose metabolism by adrenomedullin. Endocrinology 137:2626–2632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monici M 2005 Cell and tissue autofluorescence research and diagnostic applications. Biotechnol Annu Rev 11:227–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Winkel M, Maes E, Pipeleers D 1982 Islet cell analysis and purification by light scatter and autofluorescence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 107:525–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Winkel M, Pipeleers D 1983 Autofluorescence-activated cell sorting of pancreatic islet cells: purification of insulin-containing β-cells according to glucose-induced changes in cellular redox state. 1983 Biochem Biophys Res Commun 114:835–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnop M, Grupping A, Hoorens A, Bouwens L, Pipeleers-Marichal M, Pipeleers D 2000 Endocytosis of low-density lipoprotein by human pancreatic β cells and uptake in lipid-storing vesicles, which increase with age. Am J Pathol 156:237–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fend F, Raffeld M 2000 Laser capture microdissection in pathology. J Clin Pathol 53:666–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson U, Olsson A, Gabrielsson S, Nilsson B, Korsgren O 2003 Inflammatory mediators expressed in human islets of Langerhans: implications for islet transplantation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 308:474–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piemonti L, Leone BE, Nano R, Saccani A, Monti P, Maffi P, Bianchi G, Sica A, Peri G, Melzi R, Aldrighetti L, Secchi A, Di Carlo V, Allavena P, Bertuzzi F 2002 Human pancreatic islets produce and secrete MCP-1/CCL2: relevance in human islet transplantation. Diabetes 51:55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan AN, Bottino R, Giannoukakis N, Smetanka C 2006 Prospective and challenges of islet transplantation for the therapy of autoimmune diabetes. Pancreas 32:231–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraskevas S, Maysinger D, Wang R, Duguid WP, Rosenberg L 2000 Cell loss in isolated human islets occurs by apoptosis. Pancreas 20:270–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emamaullee JA, Shapiro AMJ 2006 Perspectives in diabetes. Interventional strategies to prevent β-cell apoptosis in islet transplantation. Diabetes 55:1907–1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Martens GA, Hinke SA, Heimberg H, Pipeleers D, Van de Casteele M 2007 Increased oxygen radical formation and mitochondrial dysfunction mediate β cell apoptosis under conditions of AMP-activated protein kinase stimulation. Free Radic Biol Med 42:64–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran S, Desai NM, Goers TA, Benshoff N, Olack B, Shenoy S, Jendrisak MD, Chapman WC, Mohanakumar T 2006 Improved islet yields from pancreas preserved in perflurocarbon is via inhibition of apoptosis mediated by mitochondrial pathway. Am J Transplant 6:1696–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori O, Miyazaki M, Tamatani T, Ozawa K, Takano K, Okabe M, Ikawa M, Hartmann E, Mai P, Stern DM, Kitao Y, Ogawa S 2006 Deletion of SERP1/RAMP4, a component of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) translocation sites, leads to ER stress. Mol Cell Biol 26:4257–4267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakonczay Z, Takacs T, Boros I, Lonovics J 2003 Heat shock proteins and the pancreas. J Cell Biol 195:383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.