Summary

We have outlined the carefully orchestrated process of CD4+ T-cell differentiation from naïve to effector and from effector to memory cells with a focus on how these processes can be studied in vivo in responses to pathogen infection. We emphasize that the regulatory factors that determine the quality and quantity of the effector and memory cells generated include (i) the antigen dose during the initial T-cell interaction with antigen-presenting cells; (ii) the dose and duration of repeated interactions; and (iii) the milieu of inflammatory and growth cytokines that responding CD4+ T cells encounter. We suggest that heterogeneity in these regulatory factors leads to the generation of a spectrum of effectors with different functional attributes. Furthermore, we suggest that it is the presence of effectors at different stages along a pathway of progressive linear differentiation that leads to a related spectrum of memory cells. Our studies particularly highlight the multi-faceted roles of CD4+ effector and memory T cells in protective responses to influenza infection and support the concept that efficient priming of CD4+ T cells that react to shared influenza proteins could contribute greatly to vaccine strategies for influenza.

Overview and history

Over the past decade, others and we have concluded that naïve precursor T cells must undergo many steps of division and differentiation before they acquire the effector functions necessary for their many regulatory activities (1). One of these activities is ‘help’ for B cells, which promotes B-cell isotype switching, somatic mutation, and differentiation in germinal centers to plasma cells and memory cells (2–4). Another key regulatory activity carried out by CD4+ T cells involves help for naïve CD8+ T cells to promote their optimum differentiation into cytotoxic effectors and memory cells and to support their maintenance (5–7). In addition, there are a host of other regulatory effects of CD4+ effectors on macrophages as well as other antigen-presenting cells (APCs). These CD4+ T-cell functions are mediated by surface coreceptors on the effector cells, including CD40L, CD28, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4, etc., that interact with receptors on B cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, or other APCs, and by potent cytokines secreted by the CD4+ effectors upon recognition of antigen on APCs.

CD4+ T-cell effectors represent a collection of distinct subsets characterized in part by their abilities to produce different patterns of cytokines. The two best characterized subsets are designated T-helper 1 (Th1), producing interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and Th2, producing interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13 as ‘signature’ cytokines. Recently, evidence has accumulated for a third subset that produces IL-17 (Th-17) (8). The development of the distinct subsets is itself determined to a great extent by cytokines. Development of Th1-polarized cells is promoted by IL-12 and IFN-γ and inhibited by IL-4 (9, 10), and the development of Th2-polarized T cells is promoted by IL-4 and inhibited by IFN-γ. Thus, as subsets become polarized, their autocrine secretion of cytokines intensifies the further development of their Th1 or Th2 pattern. The development of Th-17 is dependent on IL-23 and inhibited by either IL-4 or IFN-γ (8). Most probably the APCs that stimulate the naïve CD4+ T cells are also the initial source of cytokines that imprint these subsets in situ (11). It is also increasingly accepted that the polarizing cytokines secreted by the APCs are dictated by the context of the antigen, be it from a pathogen or some alternate source. Alternately, CD4+ T cells can become regulatory T cells, which act to down-modulate CD4+ T-cell responses. These cells have been extensively reviewed in recent publications (12, 13) and will not be included here.

The different cytokine-defined CD4+ T-cell subsets have very different functions related directly to the spectrum of cytokines they produce. Th1 effectors are most important in regulating responses to intracellular pathogens, while Th2 effectors seem most essential for clearance of certain parasites (14). The Th-17 cells have been implicated in autoimmune pathogenesis (15, 16), but they also would be expected to have some role in control of some disease, although this role is not yet clearly identified.

The effectors, once generated, carry out their multifaceted activities upon re-encounter with peptide antigen/APC (17). They also have the potential to develop into long-lived memory CD4+ T cells that can respond more quickly and vigorously when they again recognize antigen (18). This secondary or ‘primed’ response is one of the key factors in protection against pathogens after either primary infection or vaccination.

In this review, we focus on the regulation of the transition of CD4+ effectors to CD4+ memory T cells. In particular, we focus on the issue of whether different effectors at different stages in their development are able to progress to memory and whether this progression is induced by specific positive signals or is stochastic, and whether the transition is inherently rapid or more gradual.

Throughout this review, we have used a model of influenza infection to evaluate the generation of CD4+ T-cell effector subsets and their progression to memory cells (19). Many of the conclusions we have reached in the more simplified and reductionist model antigen systems have been found to apply to this more complex setting of viral infection. Moreover, the infection model has started to reveal additional aspects of the CD4+ T-cell response that we did not anticipate. The growing threat of the development of a new pandemic strain of influenza from the circulating avian influenza strains, due to mutation or to reassortment between the avian and human strains, reinforces our appreciation of the importance of developing vaccine approaches that promote the best possible immunity to the broadest range of influenza strains. The ability of T cells immune to heterosubtypic determinants to participate in protective responses to influenza is well-established, and we believe that vaccines based on strategies to optimize CD4+ T-cell immunity will have substantial potential to provide cross-species protection from the lethal effects of emerging strains of influenza.

Rules governing effector generation

Many factors that regulate the generation of CD4+ effector T cells from naïve T cells have been identified over the last two decades. The ability to generate CD4+ effectors in vitro (10, 20, 21) facilitated the identification of necessary components, which at the very least include antigen presented by class II positive APCs and costimulatory ligands coexpressed on the APCs, such as the combination of B7 (B7.1, B7.2; CD80, CD86) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (CD54) (22, 23). These peptide-expressing APCs need to be present for at least 2–3 days for optimum effector development (24, 25). The antigen must be present at sufficient density, and IL-2, either autocrine, produced by the responding naïve cells, or added exogenously (26), is necessary for sustained division (25) and for the sustained differentiation of the responding cells into highly differentiated effectors (25, 27). The importance of IL-2 is underscored by the defects seen in naïve CD4+ T cells from aged animals. The most obvious defect in the aged cells is a reduced ability to make IL-2, which results in diminished effector generation and production of poorly functional memory (27–29). The defects in effector generation are overcome to a large extent by addition of exogenous IL-2 to the ‘aged’ cells (27).

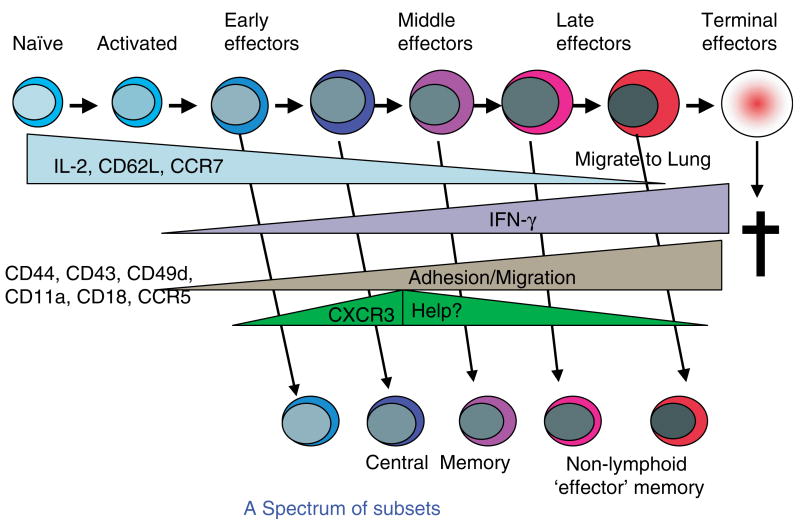

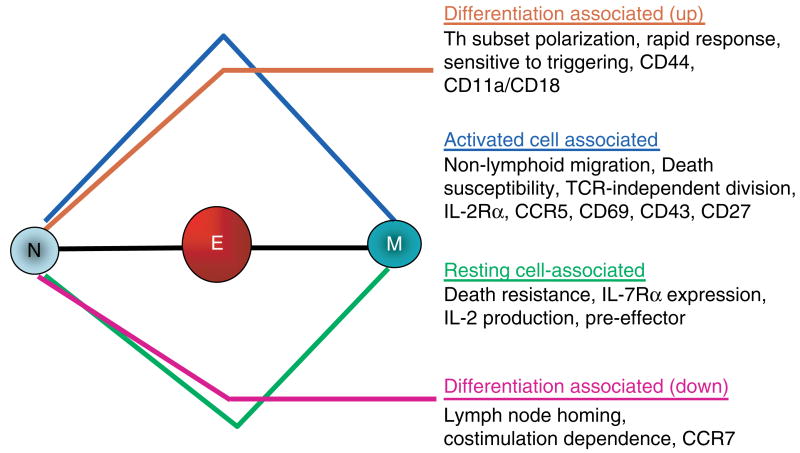

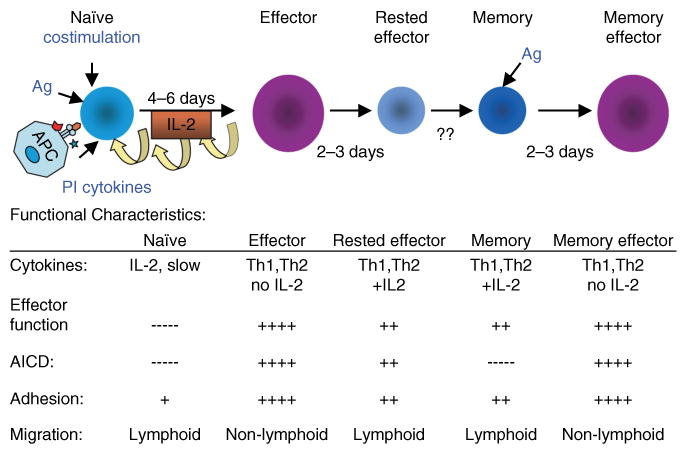

Many laboratories reported long ago that cytokines now classified as ‘proinflammatory’ (PI), including IL-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), also dramatically augmented effector cell generation (30–32). Over the years, these PI cytokine pathways have received less attention than the costimulatory receptor : co-receptor interactions such as CD28 : CD80/86 and others. However, we are beginning to see evidence that they may be obligatory players in models of infection. Infectious agents express ligands for Toll-like receptors (TLRs) expressed on APC precursors. Triggering of TLRs plays a central role in determining the quantity and quality of the CD4+ T-cell response generated (33). On one hand, TLR triggering induces APCs to make PI cytokines. On the other, TLR triggering causes APCs to become activated and further differentiate and to upregulate costimulatory ligands (33). This finding suggests that the naïve T cell interacting with a pathogen-activated APC may receive T-cell receptor (TCR) signals and both PI cytokines and costimulatory receptor-mediated signals (Fig. 1). We have shown recently that PI cytokines acting directly on naïve CD4+ T cells can augment not only the response of naïve CD4+ T cells from young mice but also the otherwise defective response of naïve CD4+ T cells from aged mice (28). Thus, we have added PI cytokines to our depiction of the components necessary for efficient effector generation. Fig. 1 shows the progressive differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells to effectors and memory cells and also indicates important functional characteristics of the cells at each stage.

Fig. 1. Stages of CD4+ T-cell differentiation.

This figure depicts the stages of CD4+ T-cell differentiation from naïve to memory, as we have found in our studies. Noted are the factors driving naïve expansion and differentiation, including Ag (antigen) and PI (proinflammatory) cytokines. Also shown under functional characteristics are benchmark features that distinguish the different stages.

The effectors produced under optimum conditions of antigen, costimulation, and PI cytokines in vitro develop benchmark characteristics that endow them with their functions. They are polarized toward either Th1 or Th2 cytokine production (26, 27) and are poised to respond rapidly by producing high levels of cytokines upon restimulation (34). Such fully differentiated effectors can be efficiently restimulated by a wide range of APCs, including those bearing very low levels of antigen and no costimulatory ligands (35) (Fig. 1, functional characteristics). The process of differentiating to a full effector state takes 4–5 days in vitro (26, 35) and a day or so longer in vivo after introduction of either protein in adjuvant (36) or to infection with influenza virus (19).

In vitro cytokine polarization can be achieved efficiently by addition of IFN-γ or IL-12 and blocking of IL-4 to generate effectors with a Th1 profile and addition of IL-4 and blocking of IFN-γ to generate a Th2 profile (9, 10, 20). These polarizing conditions produce Th1 effectors, which secrete IFN-γ and other canonical Th1 cytokines [TNF-β, lymphotoxin-α (Ltα)] but no IL-2 or IL-4, and Th2 effectors, which produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 but little or no IFN-γ. This state of extensive polarization is stable in that it is not easily reversed, because it is maintained by epigenetic changes at the level of chromatin (37, 38). Indeed, we showed over a decade ago that in vitro-generated Th1 and Th2 effectors would develop into comparably polarized memory cells after adoptive transfer, and even a year later when we recovered CD4+ memory cells, they responded by producing the appropriate pattern of cytokines (39).

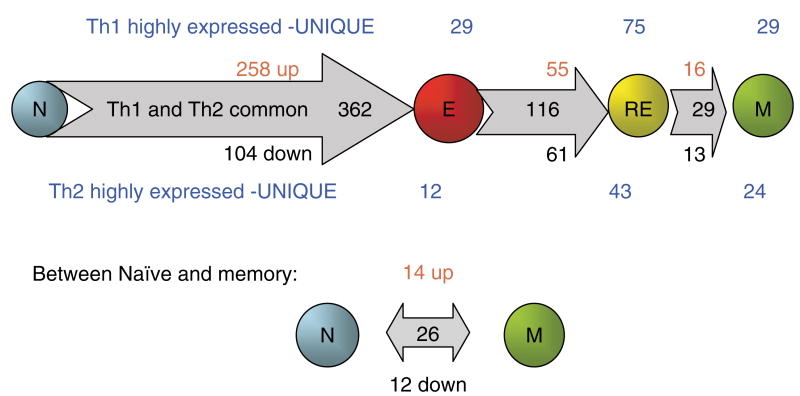

In collaborative studies, we have characterized the gene expression profile of both Th1 and Th2 effectors compared with the naïve CD4+ T cells that gave rise to them (Fig. 2). We observed that effectors had a dramatically altered profile compared with naïve CD4+ T cells. We used custom-made gene filters that contained over 4000 distinct mouse lymphocyte-expressed genes obtained by screening over 15 000 unique cDNA clones. The differentially expressed genes expressed by each subset were identified based on statistical analysis and confirmed using real time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Of 4000 selected lymphocyte-expressed genes analyzed, 362 (nearly 10%), which were common to Th1 and Th2 effectors, were altered greater than twofold as naïve cells progressed to effectors in vitro. Some 258 genes were upregulated, and 104 were downregulated. As expected, the genes that were highly expressed in effector compared with naïve CD4+ T cells included a large number of induced genes related to (i) cell cycle and proliferation (cyclin B2, cyclin H, and others); (ii) apoptosis (caspase-3, modulator of apoptosis 1, and others); (iii) chromatin and transcription alteration (high mobility group box 1, high mobility group box 2, and others); and (iv) elevated effector and immune functions (granzyme A, granzyme B, etc.). This global change in the expression of genes involved in function is accompanied by the large size of effectors and by important functional changes indicated below. Together, this dramatic change, in a broad pattern, expressed genes suggests that the ‘effector’ phenotype constitutes a unique stage of differentiation.

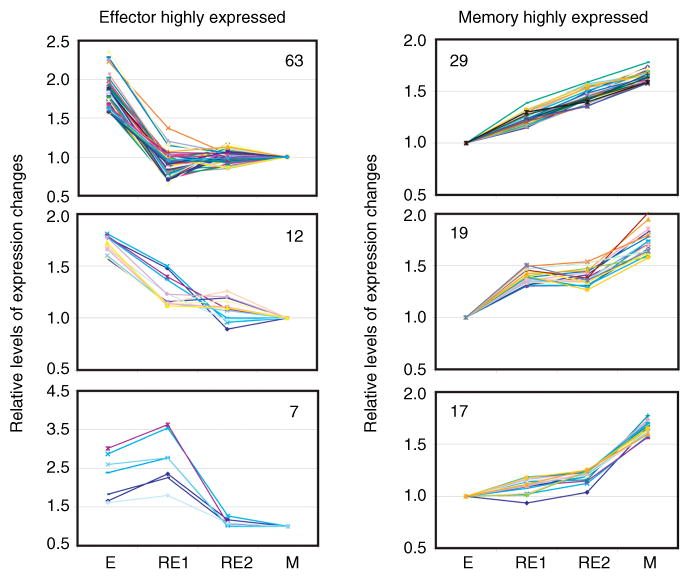

Fig. 2. Changes in gene expression: from naïve to effector to rested effector to memory CD4+ T cells.

AND T-cell receptor transgenic mice that recognize a fragment of pigeon cytochrome c (PCCF; amino acids 88–104) presented by I-Ek were used for isolation and generation of naïve, effector, rested effector, and memory CD4+ T cells (1). Th1 and Th2 effector cells were generated in vitro through incubation of naïve CD4+ T cells for 4 days with antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and PCCF in the presence of interleukin (IL)-2, IL-12, and anti-IL-4 antibody for Th1 and IL-2, IL-4, and anti-interferon-γ for Th2. Rested effector cells were derived from the effector cells, after removal of antigen and cytokines, cultured for additional 3 days in vitro. Memory cells were isolated from host mice after 4–12 weeks of adoptive transfer of rested effector cells. RNA were isolated from CD4+ subsets of both Th1 and Th2 lineages and were used for cDNA synthesis as probes. A custom-made cDNA microarray filter consists of 4000 genes that were selected from screening over 15 000 unique cDNA clones for their expression in mouse lymphocytes. The data were derived from three independent microarray experiments. The differentially expressed genes met the two criteria: (i) they are statistically significant determined by the false discovery rate (FDR) analysis (FDR ≤ 0.05) and (ii) the intensity difference is greater than two.

In contrast to the many changes noted between naïve and effectors that were common to both Th1 and Th2 effectors, the differences in gene expression were confined to a few genes (Fig. 2). Only 41 genes of the repertoire studied showed distinct expression (greater than twofold relative difference) between Th1 and Th2 at the effector stage. This finding supports the concept that the differentiation of naïve cells to the effector stage involves a large coordinated change in the behavior of the cell that is shared by both Th1 and Th2 effectors. This contrasts to the cytokine polarization process that leads to developmentally related subsets that differ in a relatively few expressed genes, at least before restimulation of the cells by antigen.

In addition to the lower requirements for restimulation and the more rapid response, a key feature of effectors, one critically involved in their function, is their ability to migrate in large numbers to nonlymphoid tissues and also to appropriate locations within lymphoid organs (40). This relocation of effector cells is necessary so they can interact with infected cells and be stimulated in those sites to carry out their functional programs. In vitro-generated effectors express high levels of adhesion molecules including integrins, such as leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 (CD11a/CD18), very late antigen-4 (CD49), and others, such as CD44. These effectors have altered expression of selectins with the loss of L-selectin (CD62L), which is needed for lymph node homing, and increased expression of P-selectin ligand (CD162), which is needed for nonlymphoid homing. Effectors produce high levels of chemokines and express shifts in chemokine receptors including loss of CCR7 (19, 40–42), involved in lymphoid tissue location, and expression of CCR5 and other receptors, which interact with chemokines induced by inflammation in nonlymphoid sites. While resting naïve cells preferentially home to lymph node and spleen (34), in vitro-generated Th1 and Th2 effectors are able to enter all organs examined, including the lungs, peritoneum, and fat pads (42). The shift is dramatically visualized in situ, where the widespread dispersion has been widely noted (43, 44).

We have visualized effector generation in vivo by transferring naïve CD4+ T cells from TCR transgenic (Tg) mice (Thy1.1, HNT) specific for a determinant in influenza hemagglutinin (HA) to normal BALB/c mice. The donor cells were carboxyfluoresein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled, and response of the transferred cohort of cells to influenza infection can be tracked in the host by staining for the Thy1.1 congenic marker. Division is indicated by their loss of CFSE (19). The Tg T cells respond first in the draining lymph nodes (DLNs), where effectors divide at least eight times before they are found in the lung. There is also a vigorous response in the spleen, commencing 1–2 days after that in the DLNs. As effectors reach peak numbers and are most divided, a unique cohort with properties similar to the highly differentiated in vitro-generated Th1 effectors accumulate in the infected lung, where large numbers of CD4+ (and CD8+) effectors are found between 6 and 8 days after infection (19). In agreement with the profile of ‘optimum’ in vitro-derived effectors, the in vivo effectors that are recovered from lung are CFSE negative (highly divided) and have the phenotype of in vitro-generated effectors. They are also CD43 high and CD27 low. Like the most advanced effectors generated in vitro (26), they secrete IFN-γ without IL-2, and in the lung where influenza antigens are concentrated, they do so without restimulation ex vivo. This finding suggests that the effectors in the lung have been restimulated in situ (19).

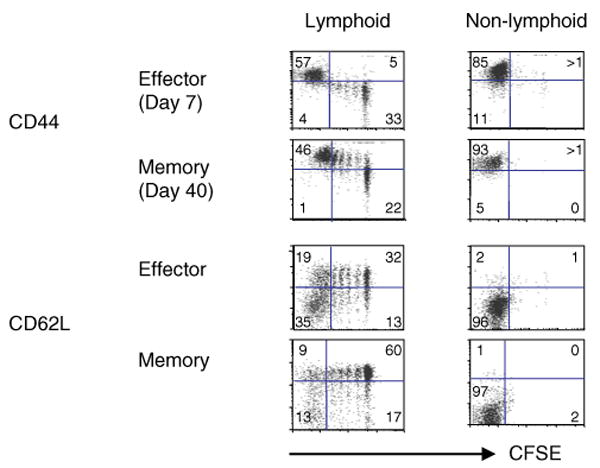

One of the striking observations from this model is that the effectors found in secondary lymphoid organs are heterogeneous (19) (Fig. 3). This heterogeneity is easily visualized in the transfer model when large numbers of naïve cells specific for influenza are added at the initiation of infection. At this high frequency of donor cells, the rate of division is slower, making the differences that occur with progressive differentiation more readily seen when a combination of CFSE staining and cell surface staining is used to visualize the donor cells (45, Roman, Jelley-Gibbs, and Swain, unpublished data) (Fig. 3). The phenotypic heterogeneity in expression of CD62L, CD49d, CCR7, and other markers linked to migration, as well as functional heterogeneity in cytokine production is still pronounced when two logs fewer naïve cells are present, although in this case, all the naïve precursors undergo extensive division (46, Roman et al., unpublished data). Therefore, when smaller numbers of donor naïve CD4+ T cells are transferred, the visualization of the subsets, which is facilitated by the distinct CFSE profiles, is less clear. Thus, this model affords us the opportunity to examine in situ the potential for the progression of a heterogeneous range of effectors to memory cells, which is discussed below.

Fig. 3. Maintenance of phenotypic heterogeneity: effector to memory.

Naïve carboxyfluoresein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled CD4+ T cells from HNT.TCR Tg.Thy1.1 mice (5 × 106) were transferred into intact BALB/c hosts. Recipient mice were infected intranasally with 0.5 LD50 of influenza A virus (A/PR8/34) a day later (19). After day 7 and 6 weeks postinfluenza infection, cell suspensions from lymphoid organs of individual mice (spleen, peripheral LN, draining LN) and nonlymphoid tissues (lung and bronchoalveolar lavage) were stained with anti-Thy1.1-biotin followed by streptavidin- allophycocyanin and anti-CD4-cychrome to identify donor T cells. The dot plots (one representative from lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues) show the expression of CD44 and CD62L against residual CFSE on gated donor cells at effector and memory stages. The dot plots representing lymphoid tissues show that heterogeneity, in terms of subpopulations at different stages of cell division and expression of CD44 and CD62L, were maintained into memory cells. Donor cells from nonlymphoid tissues remained CFSEloCD44hiCD62Llo. The maintenance of phenotypic heterogeneity was similar for the expression of many other markers analyzed (CD49d, CD11a, CCR7). These data are a representation of three individual experiments using three mice per group.

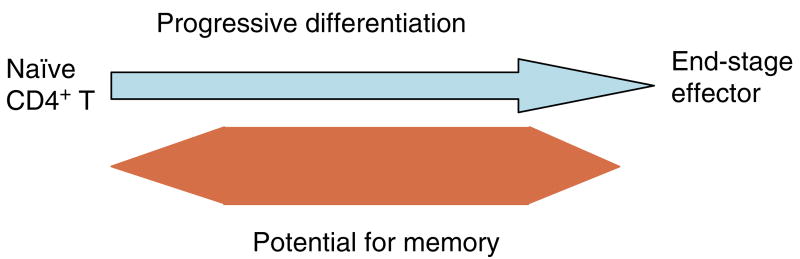

The generation of heterogeneous effectors as a consequence of progressive differentiation is illustrated in the model presented in Fig. 4 (upper portion). This model also illustrates the progressive changes in phenotypic and functional characteristics that we have observed in situ.

Fig. 4. Generating effector and memory heterogeneity.

A model depicting the postulated progressive differentiation of CD4+ T cells as they become fully differentiated effector cells. The model indicates phenotypic and functional changes that occur. The expression of helper function in the distinct subsets has not yet been tested, as indicated by the question mark. Arrows indicate the direction of progression. It is suggested that most effector subsets can become small resting memory cells, except for the naïve precursors and terminally differentiated effectors, which undergo activation-induced or programmed cell death.

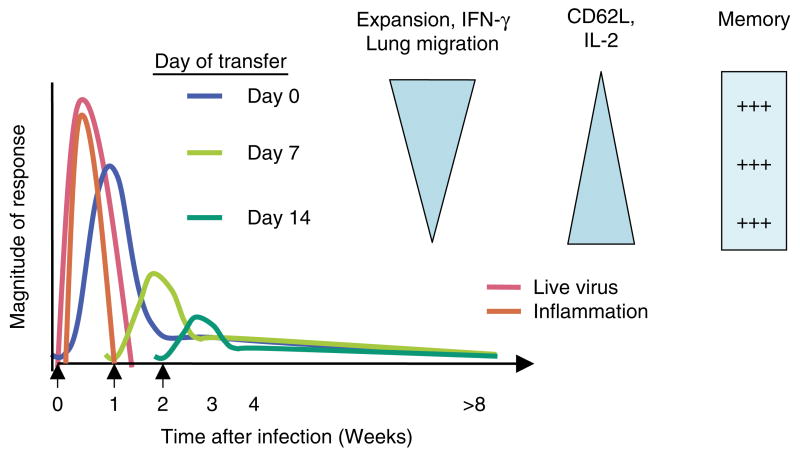

The progressive differentiation model of effector generation is useful for interpreting our recently published in vivo studies, in which we either transferred naïve CD4+ T cells at day 0, at the time of influenza virus inoculation, or added them a week or more after infection (47). In the first case, the naïve T cells were exposed to very high levels of virus for a prolonged period of time, and they were present during the time of the maximum viral induced inflammatory response (Fig. 5). Alternatively, when naïve CD4+ T cells are added 1 or 2 weeks after infection, they are exposed to much lower levels of or no live virus, resulting in fewer antigens and very little inflammation and presumably resulting in lower levels of costimulation and PI cytokines. The impact on effector generation of these different protocols is revealing. When naïve T cells are introduced coincident with viral infection, they divide extensively and expand into a large number of effectors that are highly differentiated, as indicated by phenotype (CD62Llo, CD49dhi, CD11/CD18hi, CCR7lo, etc.), by cytokine production (maximum IFN-γ without IL-2), and by their recruitment to the lung, where large numbers accumulate and make IFN-γ (19, 47) (Fig. 5). In contrast, naïve CD4+ T cells introduced 1 or 2 weeks after infection also divided extensively, but they expanded progressively less, displayed a somewhat less-differentiated phenotype, and were not found in appreciable numbers in the lung (47). This finding suggests that only the fully differentiated effectors go to the lung and that these represent the cohort that has developed under conditions of maximal stimulation (19). This study identifies variables such as the level and duration of exposure to antigen and inflammation that appear to dictate how far along the total differentiation pathway a cell will progress.

Fig. 5. Effect of antigen dose and duration and inflammation on effector differentiation and memory.

This figure depicts a summary of the results and conclusions in Jelley-Gibbs et al. (47). When naïve CD4+ influenza-specific indicator cells are introduced at day 0, they encounter high levels of virus (pink lines) and inflammation (orange line). They expand (blue lines), becoming effectors capable of high levels of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production and nonlymphoid migration to the lung. They also lose ability to produce interleukin (IL)-2. Naïve cells introduced at successively later times (1 and 2 weeks are shown) expand less and have a less pronounced effector phenotype and function, as indicated by the triangles. Memory generation, in terms of recovery of memory cells at 4 or more weeks, is equivalent.

We conclude from the effector generation studies that there are multiple stages of effector differentiation that cells progress along, as they receive signals first during direct interaction with APCs and subsequently from cytokines (25) (Fig. 4). We postulate that the extent of differentiation of responding naïve CD4+ T cells is determined by their experience of antigen dose and duration of stimulation, by the APCs with which they interact that differ in extent of activation, expression of costimulatory ligands, and by their exposure to PI cytokines from the APCs or other sources. Their extent of differentiation is also determined by the availability of growth and differentiation cytokines such as IL-2. In earlier in vitro studies, the higher levels of IL-2 supported the most differentiation (26). We also suggest that individual naïve CD4+ T cells can continue to be recruited throughout the course of the primary response and that those recruited late in the response will, because of limitations on stimulation outlined above, become progressively less differentiated with later times of recruitment (47) (Fig. 4). We also postulate that the heterogeneity so achieved contributes to the plasticity and multifaceted functionality of the CD4+ T-cell-driven components of the immune response. For instance, as we discuss below, the most highly differentiated CD4+ effectors generated in response to influenza are strongly Th1 polarized, and many migrate to the lung, where they participate in influenza clearance (19, Brown, Dilzer, Meents, and Swain, manuscript submitted) (Fig. 6, Table 1). When they re-encounter antigen in the lung, they are likely to undergo activation-induced cell death (48, 49) (Fig. 1). However, the generation of isotype-switched, somatically mutated antibody responses is probably best achieved by CD4+ helper T cells present in secondary lymphoid organs and especially by those that can access germinal centers, as suggested by Butcher and colleagues (50). Perhaps some of the somewhat less differentiated CD4+ T cells that remain in lymph node and spleen provide the most of the help, as is suggested in our model (Fig. 4), or perhaps the migration to the lung once CD4+ T cells are well differentiated is a stochastic process, and the location of the cells and what cells present antigen to them dictates their expressed function.

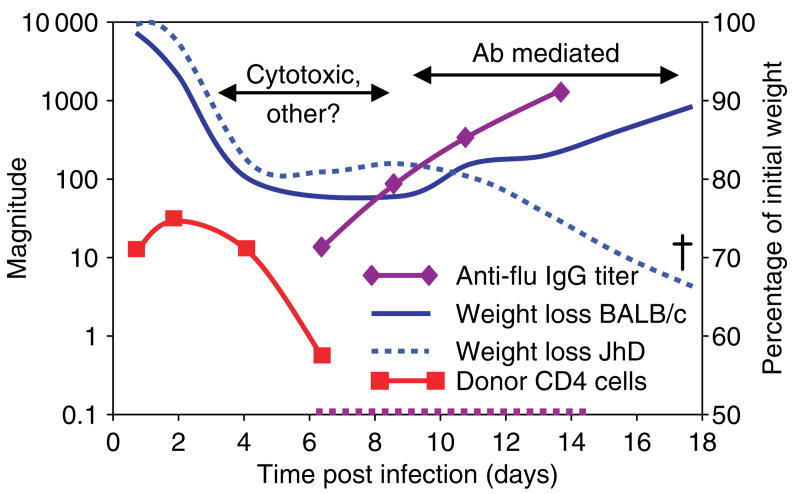

Fig. 6. Mechanism of protection by Th1 effectors: a 1–2 punch.

This illustration depicts the major mechanisms of protection revealed by the responses seen in wildtype and B-cell-deficient JhD mice. In both strains, transferred donor CD4+ Th1 cells appear in the lung soon after transfer and then decay after a few days (red line). Antibody develops early (relative to a primary encounter) in the wildtype mouse (magenta solid line), but of course not in the JhD (magenta dotted line). Weight loss plateaus in both groups, but the wildtype mice go on to gain weight (solid blue line) and recover, while the JhD mice again lose weight and die (dotted blue line). Antibody from convalescent wildtype mice, added in small amounts (10 μL), rescues the JhD hosts (not shown, see Table 1). Thus, we suggest the CD4+ effector T cells work in two stages. First, they help in the clearance of infected cells (days 3–8) using cytotoxic and perhaps other mechanisms. Second, they help host B cells to make antibody responses, which mediate viral clearance after 8 days (Brown, Dilzer, Meents, and Swain, manuscript submitted).

Table 1. Protection from otherwise lethal influenza infection.

| Donor | Host | Degree of protection |

|---|---|---|

| None | Intact, WT | − |

| Th1 (in vitro) | Intact, WT | ++++ |

| T-cell deficient (Nu/Nu) | ++++ | |

| IFN-γ KO | ++++ | |

| B-cell deficient (JhD) | ± | |

| JhD + flu antiserum (day 7) | +++ | |

| Th1. IFN-γ KO | Intact, WT | ++++ |

| T-cell deficient (Nu/Nu) | ++++ | |

| IFN-γ KO | ++++ | |

| B-cell deficient (JhD) | ± | |

| JhD + flu antiserum (day 7) | +++ | |

| Th1. Perforin KO | Intact | ++ |

| Th2 (in vitro) | Intact | ++ |

| Th2. IFN-γ KO | Intact | ± |

| Polyclonal (in vivo) | ||

| Lung CD4+ | +++ | |

| DLN CD4+ | +++ | |

| Spleen CD4+ | +++ | |

| IFN-γ−/− Lung total | +++ | |

| IFN-γ−/− Lung CD4+ | − | |

| IFN-γ−/− DLN CD4+ | − | |

| IFN-γ−/− Spleen CD4+ | − |

In all cases, hosts were mice on a BALB/c background infected with a lethal dose of PR8 influenza. Donor CD4+ Th1 or Th2 effectors were generated in vitro from HNT.T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic (Tg) mice (19) that were otherwise normal, or were interferon (IFN)-γ KO, or perforin KO. Polyclonal effectors were isolated from indicated organs at days 7–9 of an in vivo response of BALB/c mice to influenza. (Brown, Dilzer, Meents, and Swain, manuscript submitted). Degree of protection is a reflection of the rate of ‘survival’ of the mice.

Role of CD4+ effectors in influenza protection

Many of the large number of influenza-specific CD4+ effector T cells that accumulate in the lung just prior to viral clearance are secreting IFN-γ (19), suggesting that CD4+ effectors are playing one or more critical roles in the resolution of influenza. Induction of CD4+ T-cell immunity could be an important component of vaccine-induced protection against influenza, because CD4+ T cells recognize epitopes in internal influenza proteins, such as nucleoprotein and polymerase subunit PA, that are likely to be shared among strains (51). The main weakness of current vaccine strategies for influenza is that the vaccines induce antibody that is specific for exterior proteins that change each year. Influenza viruses mutate both because they are RNA viruses that lack proofreading mechanisms and because they have a segmented genome. With the eight major genes each on a separate segment, the segments readily recombine with those of other influenza viruses when coinfection occurs. A comparison of the evolutionary changes in influenza virus genes circulating in the last 100 years confirms that the HA and neuraminidase (NA) subtypes have varied extensively both because of reassortment (antigenic shift) and because of nonsilent mutations (antigenic drift). Variability in the internal proteins has been much less extensive (52–54).

Immunity induced by current inactivated subunit vaccines is mediated mostly by circulating neutralizing antibody. The antibody generated is directed primarily to the external surface HA and to a lesser extent to the NA. These antibodies are strain specific and not very effective in combating yearly variants that represent mutations within a subtype, and they are not at all effective against new subtypes. Heterosubtypic T-cell immunity does not by itself provide ‘sterilizing immunity’ like that provided by neutralizing antibody (55). Antibody, especially secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA), presents at the site and time of viral exposure and can prevent significant infection (56). Because T cells will only recognize antigen peptides generated following viral infection of cells, replication, and uptake by bystander APCs, virus will infect and replicate before T cells respond. Once primed, resting memory T cells can very rapidly secrete cytokines following restimulation (19), but our studies suggest that CD4+ memory cells take 2–3 days after that to become effectors that efficiently migrate to nonlymphoid sites such as the lung (42, Agrewala, Brown, and Swain, unpublished data) (Fig. 1, memory effectors). Thus, T-cell immunity mediated by resting or ‘central memory’ will be delayed compared with that mediated by memory cells already in the lung that are ‘effector memory’ (57). Nonetheless, even a response delayed by a few days could conceivably protect from the lethal effects of influenza infection if it were sufficiently robust.

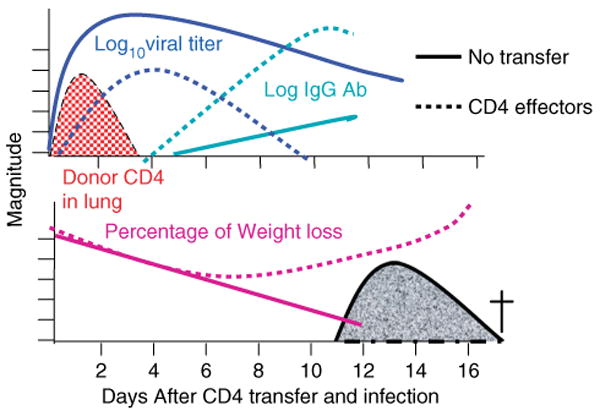

We wanted to identify to what extent specific CD4+ T-cell immunity could protect against lethality due to influenza infection and what CD4+ T-cell-mediated mechanisms were able to mediate protection. We transferred influenza-specific, in vitro-generated, TCR Tg Th1-polarized effectors into normal syngeneic hosts (19) that were then challenged with a lethal dose of PR8, a relatively pathogenic strain of influenza. Introducing CD4+ effector cells abrogated the weight loss otherwise observed after the first week of infection (Brown et al., manuscript submitted) (Fig. 7, Table 1). Most dramatically, the transferred CD4+ T cells supported survival at a range of viral doses. Mice that did not receive primed CD4+ T cells or which received naïve influenza-specific cells were not protected from weight loss, and they succumbed to lethal doses of virus (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Protection due to CD4+ effector T-cell transfer.

Influenza-specific CD4+ Th1-polarized effectors were generated in vitro. Effectors were transferred to adoptive hosts (dotted lines). Controls received no cells (solid lines). All mice were infected intranasally with 5 LD50 PR8 influenza virus. Depicted are levels of virus (log10 live viral titers) in blue, donor CD4+ T cells (log number in lung) in red, IgG antibody to influenza in serum in green, and percentage weight loss.

Several facets of this response reveal hints about the mechanism of the protection afforded by the primed CD4+ T cells. First, the in vitro CD4+ effectors were as effective in T-cell-deficient nu/nu hosts, and they did not depend on production of IFN-γ, because they were equally protective when they were derived form IFN-γ knockout donor (Brown et al., manuscript submitted) (Table 1). The in vitro-generated effectors were able to specifically kill peptide-pulsed targets by a mechanism dependent on perforin, and in turn, perforin-deficient effectors were less efficient in reversing weight loss and promoting survival (Table 1). This finding suggests that some component of the primed CD4+ T-cell efficacy is due to cytotoxic attack, presumably on virally infected host epithelial cells.

A major clue to other aspects of the mechanism of action of CD4+ effector T cells came from the fact that CD4+ effectors failed to protect when they were introduced into B-cell-deficient JhD mice that were then challenged with influenza. The addition of effectors did have a transient effect, slowing weight loss in the first week of infection; however, in a few days, the B-cell-deficient mice again started to lose weight and eventually died (Table 1, Fig. 6). One interpretation of the failure of protection in B-cell-deficient mice is that the donor CD4+ T cells act in large part indirectly, by inducing an antibody response, which is then directly responsible for protection. Indeed, the antibody titers in adoptive hosts receiving transferred CD4+ T cells rose much more rapidly and dramatically in response to influenza infection (Brown et al., manuscript submitted). To further evaluate this hypothesis, we introduced small amounts of antibody-containing serum 1 week after the transfer of CD4+ effector T cells and lethal virus infection. The influenza-specific serum, but not control serum, protected the B-cell-deficient hosts reconstituted with CD4+ T cells but not those without T cells (Table 1). Mice receiving serum alone did not survive. These observations support the concept that there are multiple roles for CD4+ T cells in protection against lethal influenza infection. They suggest that CD4+ T cells can provide both killer and helper type activities. Furthermore, these results provide proof of principle that primed CD4+ T cells in consort with host B cells can provide effective protection against influenza infection.

Although a monoclonal population of in vitro-generated CD4+ effectors could promote survival to lethal influenza, we wondered to what extent broadly specific CD4+ T-cell immunity generated by sublethal infection would protect against lethal influenza. Such in situ-generated cells are most likely to include ones that can react against new emerging influenza strains as well as historical ones, which will not share HA or NA determinants but will share ‘heterosubtypic’ ones. Mice were primed by a sublethal (500 EIU) dose of influenza PR8 and isolated from both nonlymphoid (lung) and lymphoid (spleen DLN) tissues. Most impressive was the ability of in vivo-primed CD4+ effectors from all organs tested to provide protection upon adoptive transfer (Table 1). IFN-γ knockout mice did not generate protective CD4+ effectors. This outcome could be a consequence of a requirement for IFN-γ at any point in effector generation or action. It is tempting to suggest that IFN-γ produced by in vivo effectors also can contribute to protection. Further studies of the mechanisms of protection used by the in vivo-generated effectors are in progress.

Our data strongly support the concept that CD4+ T cells have multiple functions that contribute to their ability to protect from lethal influenza infection. As discussed above, the mechanisms used by effector cells to mediate help for B cells may be fundamentally distinct from those that mediate other CD4+ T-cell functions, such as the cytotoxic activity we detect among Th1-polarized in vitro-generated effectors.

Recently, we have been examining the impact of deficiency in SLAM-associated protein (SAP) on helper T-cell function. In response to influenza infection, SAP-deficient CD4+ T cells expand normally, develop into Th1 effector cells, and are maintained long-term in normal numbers after infection with influenza; yet, they are defective in their ability to drive B-cell responses (Kamperschroer, manuscript submitted). SAP-deficient mice develop a nearly normal anti-influenza IgM antibody response, but primary expansion of B cells and plasma cells of all other isotypes are dramatically reduced, leaving the mice with approximately 100-fold less circulating antiviral IgG. Interestingly, IgA responses are more independent of SAP expression. Mice with defective SAP can control a ‘sublethal’ influenza infection. However, when mice primed by such sublethal infection receive a secondary high dose challenge, the wildtype but not the SAP-deficient mice control infection. Additionally, ‘immune’ serum from wild-type mice transferred into naïve mice allows them to survive a dose of influenza that is lethal for unprimed mice, whereas immune serum from SAP-deficient mice does not transfer protection from lethal influenza infection (Kamperschroer, unpublished observations). Although SAP-deficient CD4+ T cells have a defect in production of Th2 cytokines, this defect does not seem to be responsible for their inability to promote B-cell responses because polarization of SAP-deficient CD4+ T cells toward Th2 in vitro restores Th2 cytokine production but does not restore B-cell help upon adoptive transfer into mice. These studies support the concept that B-cell help for generation of mature antibody responses is mediated by SAP-dependent CD4+ functions that are distinct from other CD4+ functions that are SAP independent. This supports the hypothesis, discussed above, that CD4+ effectors that help B cells use different mechanisms than those that act directly in the lung to clear virus. They may be either distinct cells or cells at different stages in development (as depicted in Fig. 3), or they may be the same cells that carry out a spectrum of functions dictated by the particular signals they receive when they are restimulated by an APC.

Effector to memory transition: effector to rested effector to memory

In contrast to the many steps involved and factors required in the generation of highly differentiated effector T cells, the transition from effector to memory cells seems a simple one. When effectors generated in vitro (or in vivo) are transferred to adoptive hosts, they develop into memory cells without any intentional stimulation (39, 58, 59, Roman and Swain, unpublished data) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Patterns of expression of stage-specific genes: the transition from effector to rested effector to memory.

Th2 effector cells were generated in vitro as described in Fig. 2. Naïve CD4+ T cells, from an AND T-cell receptor (TCR) receptor mouse that was transgenic for green fluorescence protein (GFP), were incubated with antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and PCCF in the presence of interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, and anti-interferon-γ (IFN-γ) for 4 days. In vitro-rested effector cells (RE1) were derived from these effector cells, by washing and reculturing in the absence of antigen and cytokines for an additional 3 days. In vivo-rested effectors (RE2) were obtained by transferring Th2 effectors to class II knockout hosts. Donor cells were recovered 3 days later (RE2) from the hosts using fluorescence-assisted cell sorting for GFP+ cells. Memory cells were isolated from the host mice receiving effectors 4–12 weeks after adoptive transfer. Gene expression experiments and selection of differentially expressed genes were the same as shown in Fig. 2. Shown are the levels at each stage of the genes that were most highly expressed in effectors cells (left), or memory cells (right), grouped into clusters with similar patterns (Weng NP et al., unpublished data). E = effector; M = memory.

Many of the key functional attributes of effector cells are maintained by the memory cells to which they give rise. These attributes include the following: (i) rapid production of cytokines after restimulation (26, 60); (ii) polarization of cytokine production (39); (iii) responsiveness to relatively lower doses of antigen (61–64); and (iv) independence from most costimulatory requirements (64) (Fig. 1, functional characteristics). Memory cells also continue to express higher levels of some adhesion molecules, including CD44, CD49d, and CD11a/CD18, which may enable memory cells to interact more efficiently with APCs and stromal cells that provide survival factors (34, 61).

Memory cells also have a set of phenotypic and functional activities that represent a re-acquisition of features of naïve cells. They are small resting cells that are resistant to activation-induced cell death (62, 65), and they express lower levels than effectors of many adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors (19). This loss of activation-associated adhesion properties is presumably responsible for their loss of ready access to nonlymphoid sites (Agrewala et al., unpublished data) (Fig. 1, functional characteristics). In addition to their ability to produce polarized cytokines, memory CD4+ T cells also re-acquire the ability to produce IL-2 (26, Roman, McKinstry, and Swain, unpublished data), as depicted in Fig. 1.

Gene expression profile analysis also suggests that the majority of the changes associated with the transition from CD4+ effector to memory T cells occur coincident with the return of the cells to a resting state. Three days after washing and reculture in media without cytokines or antigen, cells return to a resting state (59). These ‘rested effectors’ display a pattern of gene expression that closely resembles that of resting memory cells. The pattern seen in gene array analysis depicted in Fig. 2 indicates that effector to rested effector transition in vitro involves changes in expression of a relatively large number of genes, 116 of the 4000 lymphocyte-expressed genes analyzed. This can be compared with the changes that occur over the remainder of the transition to memory. When the rested effectors are compared with effectors transferred to class II knockout hosts and left for 8 or more weeks to become memory cells, we observed changes in expression between them of only 29 of the 4000 genes. If effectors are rested in vivo, instead of in vitro, by transfer of effectors to class II negative hosts, the transition from effector to memory pattern of expression is even more pronounced (Fig. 9). When we analyzed in vivo-rested effectors, 3 days after transfer by re-isolating them from the hosts, the progression was even more complete. Fig. 9 shows the profile of selected genes that were highly expressed in either effectors (left) or memory cells (right). This analysis shows the comparison of in vitro-rested effectors (RE1) and in vivo-rested effectors (RE2). Of the 82 genes that decline from the effector to memory stage, all have changed to near memory levels after the in vivo rest. Of memory highly expressed genes, 48 of 65 were well on their way to memory levels in rested effectors. For only 17 of the 65 genes were the levels in effector and rested effectors comparable. This analysis of the 147 most differentially expressed genes between effector and memory thus indicates that 89% of the changes in expression occurred during the transition from effector to rested effector.

Fig. 9. Stages of CD4+ T-cell responses: receptors and functions.

Depicted are changes in known functions and related receptors and markers as naïve cells become effector and then memory cells. We have suggested a bipartite separation that occurs during the effector to memory transition. Many functions and surface receptors associated with activation state of the T cells go either up or down with effector development (blue, up; green, down), and these return to naïve levels when the cells become resting memory. Others, which are associated with differentiation and the improved response potential of memory cells, stay at effector levels (orange, up; magenta, down).

Genes highly expressed in memory cells include those involved in (i) cell survival and growth (Il7r, Ltb, etc.); (ii) signaling and immune function (Igtp, Tgtp, etc.), and chromatin modification and transcription (Dnmt3l, Jun, etc.). Both the naïve and the memory CD4+ T cells we examined in our studies are small resting lymphocytes, and the majority of genes they express in their resting state are shared. We detected significantly different expression of only 26 of the 4000 lymphocyte-expressed genes, when we compared the memory cells to the original naïve cells (Fig. 2). Thus, we suspect the changes in gene expression detected in the microarray analyses are to a large extent a reflection of the activation state of the cells. In contrast, we believe that epigenetic changes in chromatin structure that affect the potential for altered gene expression following restimulation are not usually detected in this analysis, because they are not expressed. Such epigenetic remodeling may be involved in facilitating a rapid memory response in the event of subsequent re-encounter of the same antigen. Analyses of stimulation-induced gene expression changes of both naïve and memory cells are currently underway and, combined with the results without restimulation, should point the way to genes whose expression explains the distinct function of memory cells compared with that of naïve cells.

On the basis of available data, we suggest that the naïve to effector transition could be conceptualized as a bipartite change, including, on one hand, the acquisition of permanent epigenetic changes that will be carried forward to memory, and on the other, activation-associated changes, which will be lost as effectors become resting memory cells. This concept is illustrated in Fig. 9.

For CD4+ T cells, the effector to memory transition can be defined by several important benchmark features that others and we have identified over the last decade. These features include the following: (i) reversion to a resting state; (ii) downregulation of expression of IL-2Rα and upregulation of IL-7Rα (Li and McKinstry, unpublished data); (iii) re-acquisition of the ability to produce IL-2 (Roman, McKinstry, and Swain, unpublished data); (iv) loss of susceptibility to activation-induced cell death (62); and (v) loss of the ability to migrate to nonlymphoid sites resulting in a concentration in secondary lymphoid organs (Agrewala et al., unpublished data). By those criteria, rested CD4+ effector cells are almost indistinguishable from memory cells. Effectors generated and rested in vitro are small cells in G0 of cell cycle. They are also IL-2Rα low, and unlike effectors, they do not divide in response to IL-2 or other common γ-chain cytokines (59). Resting causes effectors to re-express the IL-7Rα (CD127) (66, Roman et al., unpublished data). CD127 expression is highest on resting naïve and memory cells and is downregulated during the generation of effectors in vitro (66). Interestingly, resting effectors no longer migrate efficiently to nonlymphoid sites such as the lung and peritoneum, and they have partially downregulated a spectrum of adhesion receptors and ligands that are likely to be involved in that migration (Agrewala et al., unpublished data). Rested effectors also have regained the ability to produce IL-2 (Roman et al., unpublished data). We are currently evaluating whether and how quickly susceptibility to activation-induced cell death changes as effectors return to a resting state. However, the overall pattern that emerges examining these key functions is that the transition of effectors to memory cells seems to be largely completed by the time effectors return to a resting state.

Further support for the conclusion that CD4+ memory T cells are different from rested effector cells only in a few ways comes from two additional kinds of evidence. First, other than interaction with survival signals, we have found no signals required for the effector to memory transition. The transition in vitro and in vivo occurs quickly, once antigen and cytokines are removed experimentally (59). Transfer of effectors to class II knockout hosts results in their transition to resting non-dividing cells within a few days. The population of donor cells remains stable, and the cells display memory functions thereafter (59). This finding indicates that neither antigen nor class II recognition is required for the effector to memory transition. Moreover, the Rajewsky laboratory (67) has shown that survival of memory CD4+ T cells does not require TCR expression. We also found that the effector to memory transition that occurs in the adoptive transfer model can occur without division when rested effectors, rather than activated effectors, are transferred (59). In these analyses, the recovery of memory cells was sufficiently high as to suggest that most of the rested effector cells become memory cells. The only positive signals that have been identified are those that function by mediating survival. We found that IL-7, which at physiologic levels is a survival factor but does not support division, was necessary for the in vivo transition from effector to memory stages (66).

If, indeed, the resting effector to memory transition involves no ‘differentiation’ or division-dependent epigenetic events, one might predict that a functionally and phenotypically heterogeneous population of effectors should give rise in vivo to a comparably heterogeneous population of memory cells, once antigen is gone. This outcome would be particularly expected for those functions and markers that are shared between effectors and memory and that are not associated with the resting or activated state of the cells. We have started to evaluate whether this case applies in vivo in the response to influenza. When naïve CFSE-labeled cells are transferred and the response to influenza is visualized, heterogeneous effector populations are evident in peripheral lymphoid organs by the peak of response on days 6 and 7. After this time, virus titers decline quickly, and virus is cleared by day 10. We can compare the range of populations present just at the peak of the effector stage and a number of weeks later at the memory stage (Fig. 3, comparing effector and memory).

In the spleen and DLN cells, where a broad spectrum of division and expression of CD44, CD62L, and CD49 are seen at the peak of response, the pattern 5–8 weeks later is surprisingly similar. In the lung, where a much more homogeneous cohort is seen at the effector level, the memory cells recovered are also homogeneous (CD44hi, CD62Llo, and CD49d+). Thus, the pattern in each site at the peak of response is maintained during the memory phase.

Not only do these results suggest a default transition of effectors to memory, they also indicate that effectors at the various stages (preceding the most highly differentiated) can each give rise to memory. This hypothesis is implicit in the model in Fig. 4, which shows the progressive changes giving rise to a spectrum of effectors, which at any stage along the progression can become memory cells. Other experiments indicate that re-challenge with antigen in situ can drive these partially differentiated or ‘intermediate’ effectors to a more highly differentiated state (Roman and Swain, unpublished data).

We hypothesize this model differs from some similar progressive models from others that suggest a progressive loss of memory potential as effectors differentiate (68, 69). We suggest instead that cells at many of the stages of differentiation can become memory and that only the most (or least) differentiated lose their abilities to become memory. Our viewpoint is depicted in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10. Which effectors become memory cells?

This figure represents the model we have developed based on our studies. As naïve CD4+ T cells respond to infection, they progressively differentiate with successive rounds of division and exposure to growth and inflammatory cytokines, eventually becoming terminally differentiated effectors (as depicted also in Fig. 4). We suggest that all activated cells can become memory cells, except for those naïve cells that have not responded to antigen, and the end-stage effectors that either are destined to die or have progressed to a nonresponsive state (79).

The model also has implications for evaluating the efficiency of vaccines to induce CD4+ memory subsets. Our results suggest that the spectrum of effectors present during a CD4+ effector response to a vaccine should be predictive of the spectrum of the memory that will develop later, at least under the circumstances where there is not continuing stimulation or a high level of terminal differentiation.

Vaccine relevance

Because effector CD4+ T cells can use multiple mechanisms to combat influenza and because memory CD4+ T cells seem to differ little from the rested effector from which they are derived, we predict that memory CD4+ T cells, present in sufficient numbers, may also be able to provide protection against influenza. This concept is supported by Woodland's studies (70) and our own studies of memory CD4+ T-cell transfer (Roman and Swain, unpublished data) (Fig. 3). Many CD4+ memory functions are rapidly induced upon restimulation, but re-expression of the full effector stage requires 2–3 days (Fig. 1). Therefore, it is essential that we investigate to what extent CD4+ memory cells can be protective. These studies are now underway in the laboratory.

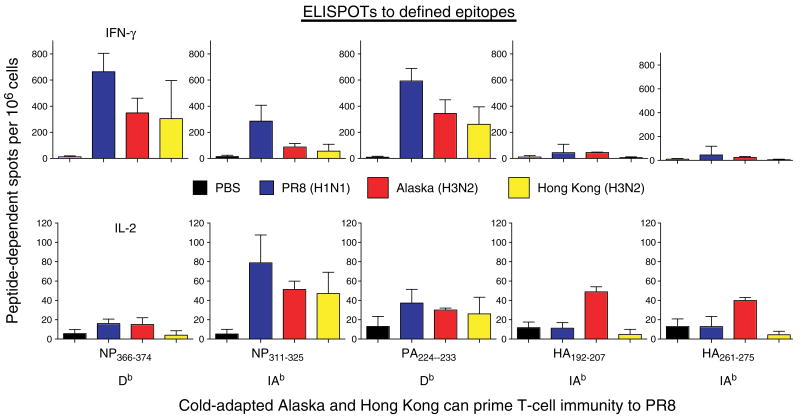

As proof of principle to support the general concept that CD4+ T-cell immunity could indeed be broadly specific, we evaluated whether CD4+ effector cells generated by strains of heterosubtypic influenza would react to epitopes of internal proteins. We examined whether T cells generated in vivo to several heterosubtypic strains of influenza will recognize epitopes identified in our PR8 virus. Cold-adapted viruses are used in the live-attenuated influenza vaccine. They replicate in the nose and upper respiratory track after intranasal administration but cannot replicate in the lower track or lung, because it is too warm (71). Thus, they might give a less vigorous response than wildtype virus. We used viruses that have been constructed with different HA and NA on the background of the cold-adapted Ann Arbor strain (kind gifts of Brian Murphy). We have mapped the class II determinants of PR8 virus in both B6 (70) and BALB/c mice (Brown, unpublished data). Indeed, the cold-adapted viruses primed T cells that reacted to both class I (presumably CD8) and class II-restricted peptides (Strutt, Hollenbaugh, Woodland, Dutton, Swain, unpublished data) (Fig. 11), as measured by IL-2 or IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot assay. Heterosubtypic protection is well established (73–78). Our recent studies support the concept that attenuated live viruses of one strain can induce quite impressive responses that cross-react with a different virulent strain (in this case mouse-adapted PR8) with different external proteins. The results warrant further exploration of the ability of cold-adapted viruses to prime CD4+ T-cell memory that could be harnessed to participate in protection against a new strain of influenza.

Fig. 11. Heterosubtypic CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses.

B6 mice were uninfected (black) or infected with either PR8 (blue), cold-adapted Alaska (red), or cold-adapted Hong Kong (yellow) influenza virus to test whether heterosubtypic responses to internal proteins (NP, PA) would be generated. Spleen cells from sublethally infected mice were tested for interferon-γ (IFN-γ)- and interleukin (IL)-2-producing enzyme-linked immunospots (ELISPOTs) following stimulation with influenza peptide-pulsed antigen-presenting cells (Strutt, Hollenbough, Dutton, Roberts, Woodland, and Swain, unpublished data). Peptides were identified using screening overlapping 15-mers, as described in our earlier report (71).

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: HL63925, AI021600, AI46530, AG025805, and Trudeau Institute, Inc.

The authors are most grateful to Dr Richard W. Dutton for his helpful comments during the editing process.

References

- 1.Swain SL. Lymphocyte effector functions – lymphocyte heterogeneity – is it limitless? Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:332–335. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkelman FD, et al. Lymphokine control of in vivo immunoglobulin isotype selection. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:303–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Antigen-specific memory B cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:487–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garside P, Ingulli E, Merica RR, Johnson JG, Noelle RJ, Jenkins MK. Visualization of specific B and T lymphocyte interactions in the lymph node. Science. 1998;281:96–99. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bevan MJ. Helping the CD8 (+) T-cell response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:595–602. doi: 10.1038/nri1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Northrop JK, Shen H. CD8+ T-cell memory: only the good ones last. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:451–455. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen EM, Lemmens EE, Wolfe T, Christen U, von Herrath MG, Schoenberger SP. CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature. 2003;421:852–856. doi: 10.1038/nature01441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynn TA. T(H)-17: a giant step from T(H)1 and T(H)2. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1069–1070. doi: 10.1038/ni1105-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swain SL, et al. Helper T-cell subsets: phenotype, function and the role of lymphokines in regulating their development. Immunol Rev. 1991;123:115–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seder RA, Paul WE. Acquisition of lymphokine-producing phenotype by CD4+ T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:635–673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ottenhoff TH, Bevan MJ. Host–pathogen interactions. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:439–442. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:345–352. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belkaid Y, Rouse BT. Natural regulatory T cells in infectious disease. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:353–360. doi: 10.1038/ni1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park H, et al. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langrish CL, et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubey C, Croft M, Swain SL. Naive and effector CD4 T cells differ in their requirements for T cell receptor versus costimulatory signals. J Immunol. 1996;157:3280–3289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dutton RW, Swain SL, Bradley LM. The generation and maintenance of memory T and B cells. Immunol Today. 1999;20:291–293. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01415-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roman E, et al. CD4 effector T cell subsets in the response to influenza: heterogeneity, migration, and function. J Exp Med. 2002;196:957–968. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swain SL, Weinberg AD, English M, Huston G. IL-4 directs the development of Th2-like helper effectors. J Immunol. 1990;145:3796–3806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swain SL, Weinberg AD, English M. CD4+ T cell subsets. Lymphokine secretion of memory cells and of effector cells that develop from precursors in vitro. J Immunol. 1990;144:1788–1799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Croft M, Duncan DD, Swain SL. Response of naive antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in vitro: characteristics and antigen-presenting cell requirements. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1431–1437. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dubey C, Croft M, Swain SL. Costimulatory requirements of naive CD4+ T cells. ICAM-1 or B7-1 can costimulate naive CD4 T cell activation but both are required for optimum response. J Immunol. 1995;155:45–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanzavecchia A, Lezzi G, Viola A. From TCR engagement to T cell activation: a kinetic view of T cell behavior. Cell. 1999;96:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80952-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jelley-Gibbs DM, Lepak NM, Yen M, Swain SL. Two distinct stages in the transition from naive CD4 T cells to effectors, early antigen-dependent and late cytokine-driven expansion and differentiation. J Immunol. 2000;165:5017–5026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers PR, Huston G, Swain SL. High antigen density and IL-2 are required for generation of CD4 effectors secreting Th1 rather than Th0 cytokines. J Immunol. 1998;161:3844–3852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haynes L, Linton PJ, Eaton SM, Tonkonogy SL, Swain SL. Interleukin 2, but not other common gamma chain-binding cytokines, can reverse the defect in generation of CD4 effector T cells from naive T cells of aged mice. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1013–1024. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haynes L, Eaton SM, Burns EM, Rincon M, Swain SL. Inflammatory cytokines overcome age-related defects in CD4 T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;172:5194–5199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haynes L, Eaton SM, Burns EM, Randall TD, Swain SL. CD4 T cell memory derived from young naive cells functions well into old age, but memory generated from aged naive cells functions poorly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15053–15058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2433717100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sepulveda H, Cerwenka A, Morgan T, Dutton RW. CD28, IL-2-independent costimulatory pathways for CD8 T lymphocyte activation. J Immunol. 1999;163:1133–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Croft M. Co-stimulatory members of the TNFR family: keys to effective T-cell immunity? Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:609–620. doi: 10.1038/nri1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banerjee D, Liou HC, Sen R. c-Rel dependent priming of naïve T cells by inflammatory cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:445–458. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawai T, Akira S. Pathogen recognition with Toll-like receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogers PR, Dubey C, Zhang X, Huston G, Lepak N, Swain S. Qualitative changes accompany memory T cell generation: faster, more effective responses at lower doses of antigen. J Immunol. 2000;164:2338–2346. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swain SL, et al. From naive to memory T cells. Immunol Rev. 1996;150:143–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1996.tb00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradley LM, Duncan DD, Tonkonogy S, Swain SL. Characterization of antigen-specific CD4+ effector T cells in vivo. immunization results in a transient population of MEL-14-, CD45RB- helper cells that secretes interleukin 2 (IL-2), IL-3, IL-4, and interferon gamma. J Exp Med. 1991;174:547–559. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ansel KM, Lee DU, Rao A. An epigenetic view of helper T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:616–623. doi: 10.1038/ni0703-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fitzpatrick DR, Wilson CB. Methylation and demethylation in the regulation of genes, cells, and responses in the immune system. Clin Immunol. 2003;109:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swain SL. Generation and in vivo persistence of polarized Th1 and Th2 memory cells. Immunity. 1994;1:543–552. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell DJ, Kim CH, Butcher EC. Chemokines in the systemic organization of immunity. Immunol Rev. 2003;195:58–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown DM, Roman E, Swain SL. CD4 T cell responses to influenza infection. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swain SL, Agrewala JN, Brown DM, Roman E. Regulation of memory CD4 T cells: generation, localization and persistence. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;512:113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marshall DR, et al. Measuring the diaspora for virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6313–6318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101132698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masopust D, Vezys V, Marzo AL, Lefrancois L. Preferential localization of effector memory cells in nonlymphoid tissue. Science. 2001;291:2413–2417. doi: 10.1126/science.1058867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marzo AL, Klonowski KD, Le Bon A, Borrow P, Tough DF, Lefrancois L. Initial T cell frequency dictates memory CD8+ T cell lineage commitment. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:793–799. doi: 10.1038/ni1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Powell TJ, et al. CD8+ T cells responding to influenza infection reach and persist at higher numbers than CD4+ T cells independently of precursor frequency. Clin Immunol. 2004;113:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jelley-Gibbs DM, Brown DM, Dibble JP, Haynes L, Eaton SM, Swain SL. Unexpected prolonged presentation of influenza antigens promotes CD4 T cell memory generation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:697–706. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang X, et al. Unequal death in T helper cell (Th)1 and Th2 effectors: Th1, but not Th2, effectors undergo rapid Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1837–1849. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang X, Giangreco L, Broome HE, Dargan CM, Swain SL. Control of CD4 effector fate: transforming growth factor beta 1 and interleukin 2 synergize to prevent apoptosis and promote effector expansion. J Exp Med. 1995;182:699–709. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell DJ, Kim CH, Butcher EC. Separable effector T cell populations specialized for B cell help or tissue inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:876–881. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lamb JR, Eckels DD, Phelan M, Lake P, Woody JN. Antigen-specific human T lymphocyte clones: viral antigen specificity of influenza virus-immune clones. J Immunol. 1982;128:1428–1432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:152–179. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.152-179.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Webster RG, Laver WG, Air GM, Schild GC. Molecular mechanisms of variation in influenza viruses. Nature. 1982;296:115–121. doi: 10.1038/296115a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gorman OT, Bean WJ, Kawaoka Y, Donatelli I, Guo YJ, Webster RG. Evolution of influenza A virus nucleoprotein genes: implications for the origins of H1N1 human and classical swine viruses. J Virol. 1991;65:3704–3714. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3704-3714.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ulmer JB, et al. Heterologous protection against influenza by injection of DNA encoding a viral protein. Science. 1993;259:1745–1749. doi: 10.1126/science.8456302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Treanor J, et al. Intranasal administration of a proteosome-influenza vaccine is well-tolerated and induces serum and nasal secretion influenza antibodies in healthy human subjects. Vaccine. 2005;24:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swain SL, Hu H, Huston G. Class II-independent generation of CD4 memory T cells from effectors. Science. 1999;286:1381–1383. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu H, Huston G, Duso D, Lepak N, Roman E, Swain SL. CD4(+) T cell effectors can become memory cells with high efficiency and without further division. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:705–710. doi: 10.1038/90643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stockinger B, Kassiotis G, Bourgeois C. CD4 T-cell memory. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Swain SL. Regulation of the generation and maintenance of T-cell memory: a direct, default pathway from effectors to memory cells. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:213–219. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carter LL, Zhang X, Dubey C, Rogers P, Tsui L, Swain SL. Regulation of T cell subsets from naive to memory. J Immunother. 1998;21:181–187. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199805000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carter LL, Swain SL. From naive to memory. Development and regulation of CD4+ T cell responses. Immunol Res. 1998;18:1–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02786509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Croft M, Dubey C. Accessory molecule and costimulation requirements for CD4 T cell response. Crit Rev Immunol. 1997;17:89–118. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v17.i1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grayson JM, Harrington LE, Lanier JG, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Differential sensitivity of naive and memory CD8+ T cells to apoptosis in vivo. J Immunol. 2002;169:3760–3770. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li J, Huston G, Swain SL. IL-7 promotes the transition of CD4 effectors to persistent memory cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1807–1815. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Polic B, Kunkel D, Scheffold A, Rajewsky K. How alpha beta T cells deal with induced TCR alpha ablation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8744–8749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141218898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Progressive differentiation and selection of the fittest in the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:982–987. doi: 10.1038/nri959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gourley TS, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Ahmed R. Generation and maintenance of immunological memory. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woodland DL, Hogan RJ, Zhong W. Cellular immunity and memory to respiratory virus infections. Immunol Res. 2001;24:53–67. doi: 10.1385/IR:24:1:53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murphy BR, Coelingh K. Principles underlying the development and use of live attenuated cold-adapted influenza A and B virus vaccines. Viral Immunol. 2002;15:295–323. doi: 10.1089/08828240260066242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Crowe SR, Miller SC, Woodland DL. Identification of protective and non-protective T cell epitopes in influenza. Vaccine. 2006;24:452–456. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Effros RB, Doherty PC, Gerhard W, Bennink J. Generation of both cross-reactive and virus-specific T-cell populations after immunization with serologically distinct influenza A viruses. J Exp Med. 1977;145:557–568. doi: 10.1084/jem.145.3.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fiers W, De Filette M, Birkett A, Neirynck S, Min Jou W. A ‘universal’ human influenza A vaccine. Virus Res. 2004;103:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liang S, Mozdzanowska K, Palladino G, Gerhard W. Heterosubtypic immunity to influenza type A virus in mice. Effector mechanisms and their longevity. J Immunol. 1994;152:1653–1661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Slepushkin VA, Katz JM, Black RA, Gamble WC, Rota PA, Cox NJ. Protection of mice against influenza A virus challenge by vaccination with baculovirus-expressed M2 protein. Vaccine. 1995;13:1399–1402. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)92777-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Epstein SL, et al. Mechanisms of heterosubtypic immunity to lethal influenza A virus infection in fully immunocompetent, T cell-depleted, beta2-microglobulin-deficient, and J chain-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:1222–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tumpey TM, Renshaw M, Clements JD, Katz JM. Mucosal delivery of inactivated influenza vaccine induces B-cell-dependent heterosubtypic cross-protection against lethal influenza A H5N1 virus infection. J Virol. 2001;75:5141–5150. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5141-5150.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]