Abstract

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (ERAD) is a specialized activity of the ubiquitin–proteasome system that is involved in clearing the ER of aberrant proteins and regulating the levels of specific ER-resident proteins. Here we show that the yeast ER-SNARE Ufe1, a syntaxin (Qa-SNARE) involved in ER membrane fusion and retrograde transport from the Golgi to the ER, is prone to degradation by an ERAD-like mechanism. Notably, Ufe1 is protected against degradation through binding to Sly1, a known SNARE regulator of the Sec1–Munc18 (SM) protein family. This mechanism is specific for Ufe1, as the stability of another Sly1 partner, the Golgi Qa-SNARE Sed5, is not influenced by Sly1 interaction. Thus, our findings identify Sly1 as a discriminating regulator of SNARE levels and indicate that Sly1-controlled ERAD might regulate the balance between different Qa-SNARE proteins.

Keywords: ERAD, SM proteins, SNARE, ubiquitin, Ufe1

Introduction

Membrane fusion and vesicular transport is crucially controlled by SNARE proteins, which are typically single spanning transmembrane proteins (Jahn & Scheller, 2006). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the syntaxin (Qa-SNARE) Ufe1 controls homotypic membrane fusion of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes and retrograde transport of coatomer (COPI)-coated vesicles from the cis-Golgi to the ER (Downing & Storms, 1996; Lewis et al, 1997; Patel et al, 1998). By contrast, the related Qa-SNARE Sed5 mediates anterograde transport of COPII-coated vesicles from the ER to the Golgi, and also the fusion of Golgi membranes (Hardwick & Pelham, 1992; Peng & Gallwitz, 2002). For these different functions, Ufe1 and Sed5 collaborate with a specific set of cognate SNAREs of three other SNARE classes—Qb-, Qc- and R-SNARE—to form a tetrameric SNARE bundle (Jahn & Scheller, 2006). SNARE pairing seems to be guided by proteins of the Sec1–Munc18 (SM) family, but how these proteins direct protein transport is largely unknown (Toonen & Verhage, 2003).

Accumulating evidence indicates that ubiquitin (Ub)–proteasome-dependent ER-associated degradation (ERAD) has a prominent role as regulator of several membrane-related functions (Meusser et al, 2005). Notable examples include regulated degradation of the ER-embedded enzymes HMG-CoA reductase, which regulates cholesterol levels, and Ole1, the Δ9-fatty acid desaturase from yeast, which supplies cells with unsaturated fatty acids (Braun et al, 2002; Meusser et al, 2005).

Here, we show that Ufe1 is prone to ubiquitylation and degradation by an ERAD-like mechanism. We found that Ufe1 degradation is negatively controlled by direct binding to the SM protein Sly1. Remarkably, although Sly1 binds to the Golgi synatxin Sed5 in an analogous manner, it does not regulate Sed5 stability. Thus, our findings underscore the importance of ERAD for controlling membrane function and indicate that the SM protein Sly1 might control the balance between functionally opposing SNARE proteins.

Results

The ER-SNARE Ufe1 is ubiquitylated

Previous studies have indicated that Ufe1, a Qa-SNARE that is embedded in the membrane by its carboxy-terminal tail, is short-lived but only in cells defective in protein kinase-C (Lin et al, 2001). However, as no relevant phosphorylation target for this process could be identified, the mechanism of controlled Ufe1 degradation remained unsolved.

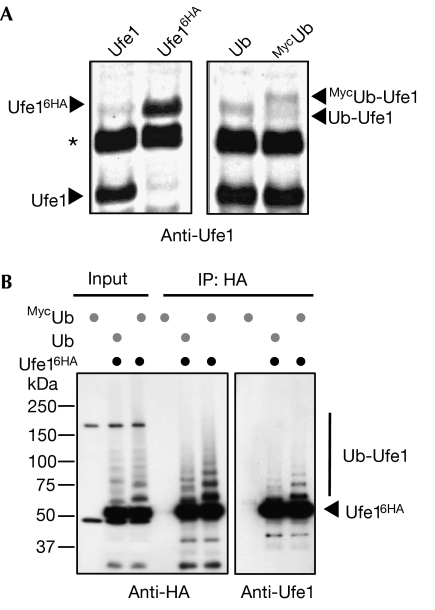

When we tested whether Ufe1 is ubiquitylated in vivo, we found that it exists at a steady state predominantly in a non-modified form (Fig 1A, left panel). However, when we overexpressed either Ub or a larger, amino-terminally Myc-tagged ubiquitin (MycUb) variant, we observed additional slower migrating species, which corresponded to the predicted Ub- or MycUb-modified forms, respectively (Fig 1A, right panel). To extend these findings, we expressed C-terminally haemagglutinin (HA)-epitope-tagged Ufe1 (Ufe16HA) in Δufe1 cells overexpressing either Ub or MycUb and then immunoprecipitated anti-HA-reactive proteins from lysates. Western blot analysis using HA- or Ufe1-specific antibodies identified a characteristic evenly spaced protein ladder, indicating that a fraction of Ufe1 is most likely modified by a polyubiquitin chain (Fig 1B). Notably, Ufe1 ubiquitylation was enhanced when we used a MycUb-expressing strain, which is consistent with the observation that conjugation with MycUb can slow down proteasomal degradation (Ellison & Hochstrasser, 1991).

Figure 1.

The ER-SNARE Ufe1 is ubiquitylated in vivo. (A) Anti-Ufe1 immunoblots of extracts from cells expressing Ufe1 or a carboxy-terminally epitope-tagged Ufe1 form (Ufe16HA; left panel), or from cells coexpressing ubiquitin or an amino-terminally epitope-tagged ubiquitin (MycUb; right panel). UFE1 (UFE16HA) was expressed from its chromosomal locus. The positions of ubiquitin- (Ub-) and MycUb-modified Ufe1 forms are indicated by arrowheads. The asterisk denotes an unrelated crossreacting protein. (B) Immunoprecipitation of C-terminally HA-tagged Ufe1 (Ufe16HA) under denaturing conditions. WT and tagged Ufe1 proteins were expressed in Δufe1 cells at endogenous levels in combination with overexpressed Ub or MycUb. The input and the precipitated material were analysed by western blots using HA- (left panel) or Ufe1-specific antibodies (right panel). The positions of unmodified Ufe1 (Ufe16HA) and ubiquitin-modified Ufe1 forms (Ub-Ufe1) are indicated. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; HA, haemagglutinin; Ub, ubiquitin; WT, wild type.

Sly1 is crucial for Ufe1 but not Sed5 stability

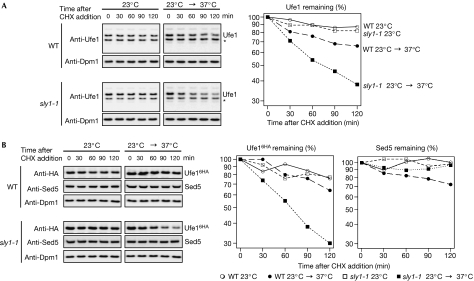

To investigate the turnover of endogenously expressed Ufe1, we performed an expression shut-off experiment by monitoring Ufe1 protein levels after the addition of the translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) to the growth medium. In agreement with the observed low level of polyubiquitylation, Ufe1—and Ufe16HA—was stable at 23°C, but moderately short-lived at 37°C (Fig 2A,B). However, when we repeated this experiment in a temperature-sensitive sly1-1 mutant (Dascher et al, 1991; Cao et al, 1998; Kosodo et al, 2002), Ufe1 degradation was significantly accelerated at 37°C, the restrictive temperature of this mutant allele. As Sly1 is a direct interactor of Ufe1, this finding indicated that Sly1 might control Ufe1 stability through direct physical interaction.

Figure 2.

Ufe1 but not Sed5 is unstable in the sly1-1 mutant. (A) CHX-chase experiment with WT (upper panel) and sly1-1 cells (lower panel). Cells were grown in YPD to an OD600 of 0.5 at 23°C and maintained at this temperature (left) or shifted up to 37°C after the addition of CHX (right). At each time point, the cellular level of Ufe1 was analysed by anti-Ufe1 immunoblots. As a control, the blots were re-probed with an antibody against the stable ER membrane protein Dpm1. The asterisk indicates a crossreactive band. The graph shows the quantification of the immunoblot signals from the Ufe1 decay (time point zero was set as 100%). (B) Similar to (A) but with strains expressing HA-tagged Ufe1 (Ufe16HA). Extracts were probed with HA (for tagged Ufe1), Sed5 or Dpm1 antibodies. CHX, cycloheximide; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; HA, haemagglutinin; OD, optical density; WT, wild type.

Sly1 is also known to bind to the SNARE Sed5, which is implicated in anterograde transport from the ER to the Golgi. As Sed5 belongs to the same SNARE family as Ufe1 and interacts with Sly1 in an analogous manner (Toonen & Verhage, 2003; Jahn & Scheller, 2006), we asked next whether Sed5 stability is equally affected by the sly1-1 mutation. However, we observed that under the same conditions Sed5 levels remained constant in the sly1-1 mutant (Fig 2B), indicating that Sly1 discriminates between the two related SNAREs.

Ufe1 stability is linked to interaction with Sly1

Sly1 carrying an R266K substitution expressed from the sly1-1 mutant allele fails to interact with Sed5 at the non-permissive temperature (Kosodo et al, 2002). Mutation studies indicated that a crucial determinant within the Qa-SNAREs is a conserved short N-terminal stretch, in which a conserved phenylalanine residue (F10 in Sed5 and F9 in Ufe1) contacts a hydrophobic pocket of Sly1 (Bracher & Weissenhorn, 2002; Yamaguchi et al, 2002; Peng & Gallwitz, 2004). However, as the amino acid altered by the sly1-1 allele lies outside this pocket, the observed defect in SNARE binding might be caused by a structural defect of this mutant protein.

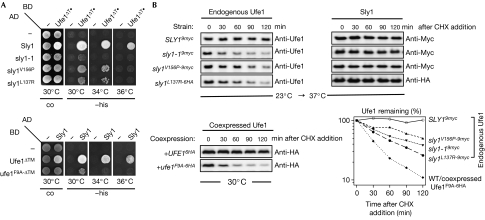

To investigate whether Ufe1 stability is linked directly to Sly1 interaction, we introduced mutations that affected the Ufe1–Sly1 interaction specifically either in the N-terminal, Sly1-interacting domain of Ufe1 (Ufe1F9A) or, reciprocally, in the SNARE-binding pocket of Sly1 (Sly1L137R or Sly1V156P). To confirm the anticipated interaction defects, we performed two-hybrid assays using a soluble Ufe1 variant that lacked the transmembrane (TM) domain of the SNARE (UFE1ΔTM). Indeed, analogous to Sed5 (Peng & Gallwitz, 2004), Ufe1 failed to interact with pocket mutant variants of Sly1 (and the Sly1-1 protein; Fig 3A); the reciprocal Ufe1 mutant protein (Ufe1F9A-ΔTM) also failed to interact with wild-type (WT) Sly1 in this assay.

Figure 3.

Loss of Ufe1–Sly1 interaction results in degradation of Ufe1. (A) Two-hybrid interactions between WT or mutant forms of Sly1 and Ufe1 fused to the activating domain (AD) or DNA-binding domain (BD) of Gal4. Transformants were spotted onto control (co) or media plates without histidine (−his) and incubated for 2–3 days. (B) Upper panel: CHX-chase experiments with Δsly1 cells expressing epitope-tagged proteins of either WT SLY1 or different sly1 mutants at endogenous level. The experimental set-up was essentially as described in Fig 2. Protein stability of Ufe1 and the respective Sly1 variant was monitored by anti-Ufe1 (left) and anti-Myc- or anti-HA immunoblots (right), respectively. Lower left panel: anti-HA immunoblot of CHX chase performed at 30°C with WT cells coexpressing plasmid-borne copies of HA-tagged variants of WT UFE1 or ufe1-F9A at endogenous level. The graph (lower right) shows quantified levels of endogenous Ufe1 and coexpressed Ufe1-F9A6HA in the respective strain backgrounds as indicated. CHX, cycloheximide; HA, haemagglutinin; WT, wild type.

Remarkably, when we examined the stability of endogenously expressed Ufe1 in these strains—sly1-1, sly1V156P, sly1L137R—we observed rapid Ufe1 degradation in all mutant backgrounds (Fig 3B, upper panel). By contrast, WT and mutant Sly1 proteins were metabolically stable in this assay, indicating that defective Ufe1–Sly1 interaction does not trigger Sly1 instability.

Next, in a reciprocal experiment, we investigated whether the Ufe1 mutant protein defective in Sly1 interaction (Ufe1F9A) is also short-lived. However, as this mutant protein cannot sustain viability of a ufe1 deletion strain (data not shown), we addressed this question by coexpressing Ufe1F9A as a C-terminally HA-tagged form (Ufe1F9A−6HA) in WT cells. Indeed, this variant was short-lived in vivo (Fig 3B, lower panel), indicating that abrogating Sly1–Ufe1 interaction by whichever means results in Ufe1 degradation.

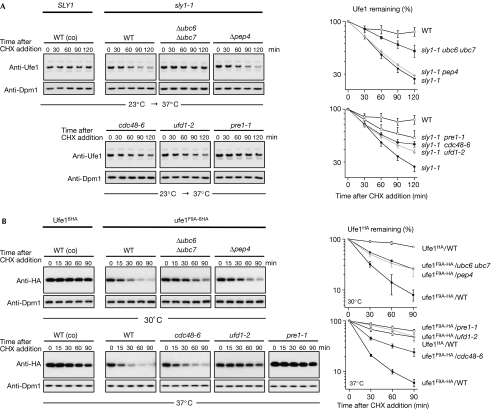

Ufe1 degradation is mediated by ERAD

Ufe1 is a SNARE of ER membranes, and thus we wondered whether Ufe1 degradation is mediated by ERAD. This pathway typically involves the ER-bound Ub-conjugating enzymes Ubc6 and/or Ubc7 (Sommer & Jentsch, 1993; Biederer et al, 1997) and the chaperone-like enzyme Cdc48, which is thought to participate in membrane extraction (Meusser et al, 2005). We introduced the corresponding mutations into the sly1-1 background and asked whether they affect Ufe1 degradation. Degradation of endogenous Ufe1 was indeed proteasome dependent and not mediated by the lysosome, as indicated by a robust stabilization in the conditional proteasomal mutant pre1-1 (Heinemeyer et al, 1991), but not in Δpep4, a mutant defective in lysosomal degradation (Fig 4A). Furthermore, Ufe1 degradation in the sly1-1 background was significantly reduced in strains deficient in Ubc6 and Ubc7 (Δubc6 Δubc7), as well as in temperature-sensitive mutants of Cdc48 (cdc48-6) or its substrate-recruiting cofactor Ufd1 (ufd1-2; Fig 4A).

Figure 4.

Destabilized Ufe1 is degraded by an ERAD-like pathway. (A) Anti-Ufe1 immunoblots of CHX-chase experiments using WT (control; co) and sly1-1 mutant cells in which additional mutations (Δubc6 Δubc7, Δpep4, cdc48-6, ufd1-2, pre1-1) were introduced. The experimental set-up was essentially as in Fig 2. Representative experiments are shown and the graphs present the quantification of the Ufe1 decay resulting from 3 to 4 independent data sets; symbols and bars represent mean and s.e. (B) Anti-HA immunoblots of a CHX-chase experiment using WT (control; co) and mutants (same as above) coexpressing HA-tagged proteins of WT UFE1 or ufe1-F9A at endogenous UFE1 levels. The experimental procedure was similar to (A) except that the strains shown in the upper panel were grown to an OD600 of 0.6 at 30°C and kept at this temperature during the time course, whereas the strains shown in the lower panel were grown to an OD600 of 0.4 at 23°C and then shifted for an additional 2 h to 37°C before the CHX chase was started. Graphs: mean and s.e. of 3–4 independent data sets (Δpep4, n=2; error bars are deviation from the mean). CHX, cycloheximide; HA, haemagglutinin; OD, optical density; WT, wild type.

Conversely, we exogenously expressed the Sly1-interaction-defective Ufe1 (ufe1F9A−6HA) variant (in addition to endogenously expressed WT Ufe1; see above) in the same set of strains and monitored its turnover. Indeed, the tested ERAD mutations also caused a stabilization of the substrate in this assay, although only partly in some mutants (Fig 4B). Apparently, the lysosome also contributed to its degradation, suggesting that a small fraction of the mutant Ufe1 variant is routed to the lysosome. Nonetheless, the above findings are consistent with the model that ERAD is the main reason for the observed instability of Ufe1 triggered by defective Ufe1–Sly1 interaction.

Sly1–Ufe1 imbalance is linked to Ufe1 degradation

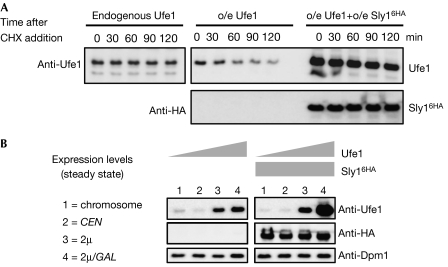

Next, we investigated whether an imbalance between Ufe1 and Sly1 triggers Ufe1 degradation. We experimentally altered the Sly1–Ufe1 ratio in cells and found that overexpressed Ufe1 was short-lived (Fig 5A). Intriguingly, however, simultaneous overexpression of Sly1 (Sly16HA) strongly stabilized overexpressed Ufe1, which thereby accumulated to high levels. We also gradually altered SNARE levels by expressing UFE1 from its genomic locus, a low-copy-number or a high-copy-number plasmid (all driven by the relatively weak UFE1 promoter), or even from a high-copy-number plasmid driven by the strong GAL1-10 promoter. Remarkably, Ufe1 levels accumulated to high steady-state levels only in those cells that also overexpressed Sly1 (Fig 5B).

Figure 5.

The ratio between Ufe1 and Sly1 affects Ufe1 stability. (A) Expression shut-off experiment monitoring Ufe1 protein stability when expressed endogenously (left panel) or on overexpression (o/e; right panel) in the absence or presence of additionally overexpressed Sly16HA. In case of overexpression, less sample was subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to visualize protein decay. (B) Steady-state levels of Ufe1 detected by anti-Ufe1 immunoblots (left panel). UFE1 was expressed from (1) its genomic locus, (2) a low-copy-number centromeric plasmid, or (3) a high-copy-number 2μ-based plasmid, in each case driven by the UFE1 promoter, or (4) from a 2μ-based plasmid driven by the GAL1-10 promoter. The panels on the right show the same experimental design except that Sly1 (Sly16HA) is co-overexpressed from a 2μ-based plasmid under the control of the GAL1-10 promoter. Dpm1 levels were used as control. HA, haemagglutinin.

Importance of Sly1–SNARE and Ufe1–Sed5 balances

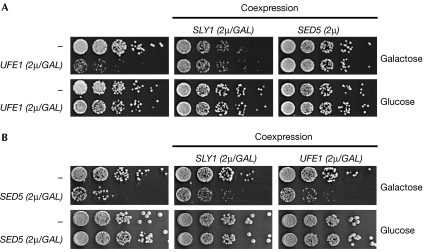

The aforementioned data indicate that one function of Sly1 is to protect Ufe1 against degradation by ERAD. We noticed that a double mutant of sly1-1 with pre1-1 (defective in proteasomal degradation) is inviable at temperatures at which the single mutants can grow (supplementary Fig S1 online); therefore, we wondered whether misregulated Ufe1 levels are detrimental to growth. Indeed, strong overexpression of Ufe1 is toxic for cells, which is, however, partly relieved by simultaneous overexpression of Sly1 to high levels (which is barely toxic on its own; Fig 6A). This indicates that it is not the high level of Ufe1 as such but the imbalance to Sly1 that is deleterious for cells. Remarkably, moderate overexpression of Sed5—the alternative SNARE partner of Sly1—restored viability, indicating that not only a Sly1–Ufe1 disparity but also an apparent imbalance between the two SNAREs is detrimental to cellular growth. Notably, strong Sed5 overexpresssion is also toxic, and either Sly1 or Ufe1 overexpression can alleviate this effect, at least in part (Fig 6B). In agreement with these genetic data, overexpression of Sed5 resulted in a moderate increase of Ufe1 degradation (supplementary Fig S2 online). These data indicate that balanced levels between Ufe1 and Sed5 SNAREs are particularly important for cells.

Figure 6.

The ratio between Ufe1, Sed5 and Sly1 affects cellular growth. (A) Cytotoxicity mediated by UFE1 overexpression is reverted by concomitant overexpression of SLY1 or SED5. Cells overexpressing UFE1 alone (left), or together with SLY1 (middle), or SED5 (right) were adapted to galactose-containing media and then plated in fivefold dilutions on media containing galactose or glucose (as control) and incubated for 2–3 days at 30°C. All constructs were expressed in the DF5 strain from 2μ-based high-copy-number plasmids under pGAL1-10 control (except SED5: endogenous promoter). Empty vectors are denoted as ‘−'. (B) Cytotoxicity mediated by SED5 overexpression is partly reverted by concomitant overexpression of SLY1 or UFE1. Cells overexpressing SED5 alone (left), or together with SLY1 (middle), or UFE1 (right) were grown in liquid synthetic media containing raffinose and then plated in fivefold dilutions on media containing galactose or glucose (as control) and incubated for 2–3 days at 30°C. All constructs were expressed in the W303 strain from high-copy-number plasmids under pGAL1-10 control.

Discussion

Our finding that SM-controlled ERAD can control SNARE levels has several implications. First, it underscores the role of ERAD in regulating membrane-linked functions and also indicates that potentially unstable ER membrane proteins can be protected against ERAD by an association with partners. More specifically, our data indicate that SM proteins can differentially control SNARE levels.

The role of SM proteins in vesicle fusion events is poorly understood. It has been suggested that they function as safeguards that protect syntaxin SNAREs from mispairing (Toonen & Verhage, 2003). More recent data indicate that they might also protect SNAREs against degradation. For example, deletion of the murine gene for the SM protein Munc18-1 causes a reduction in the level of syntaxin-1 (Toonen et al, 2005). Similarly, the yeast SM protein Vps45 protects the SNARE Tlg2 from degradation (Bryant & James, 2001), which seems to be mediated in part by ERAD (supplementary Fig S3 online). Our finding that the SM protein Sly1 controls only Ufe1 but not Sed5 levels provides a possible raison d'être for this protective mechanism. As Ufe1 and Sed5 have largely opposing cellular activities, selective degradation of only one SNARE might tip the balance and facilitate one particular direction of vesicular transport. In this speculative model, relatively high Ufe1 levels might foster retrograde transport, whereas low Ufe1 levels caused by ERAD might perhaps stimulate anterograde transport. Indeed, our coexpression experiments indicate that balancing Ufe1 and Sed5 levels might be crucial for growth. As Sed5 has a higher affinity for Sly1 than Ufe1 (Yamaguchi et al, 2002), anterograde transport might thus be favoured under normal growth conditions. However, during sporulation, UFE1 transcripts are upregulated, whereas SED5 transcripts concomitantly decrease (Chu et al, 1998). This indicates that perhaps Ufe1 can accumulate (fostering retrograde transport) only when Sed5 levels are lowered. It will be interesting to see whether, as a general rule, the various routes of vesicular transport are controlled by regulated degradation of SNAREs. Such a mechanism would allow cells to adapt their transport system to demand, for example, for sporulation, active secretion, cellular growth, apoptosis or cell division.

Methods

Yeast strains and plasmids. Unless otherwise indicated, all strains are isogenic to DF5 (Braun et al, 2002), except for the experiment in Fig 6B and supplementary Fig S2 online, for which W303 was used for overexpression of SED5. Mutant alleles from other strain backgrounds were introduced into DF5 by repetitive mating and tetrad dissection. Further details are available as the supplementary information online.

Antibodies. For raising Ufe1-specific polyclonal antibodies, His-tagged Ufe1 which lacked the C-terminal SNARE and the transmembrane domain (Ufe1ΔSnΔTM, 237–347 aa) was bacterially expressed (pQE30; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and affinity-purified under denaturing conditions. The antiserum obtained was affinity-purified against Ufe1ΔSnΔTM–GST expressed from pGEX4 (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Antibodies against Sed5 and Tlg2 were gifts from D. Gallwitz and H. Pelham, respectively.

Immunotechniques. For examination of post-translational modifications, protein extracts were prepared under denaturing conditions (Knop et al, 1999), and subjected to immunoprecipitation in PBS supplemented with 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and 0.05% SDS. After several wash steps, the bound material was eluted with 1% SDS at 65°C and analysed by western blotting. Further details are available in the supplementary information online.

Expression shut-off experiments. CHX shut-off experiments were performed essentially as described previously (Braun et al, 2002). Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports. org).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures

Acknowledgments

We thank U. Cramer and M. Kost for technical assistance, and S. Mishra for experimental help, A. Buchberger, G. Qin and D. Siepe for discussions and comments on the manuscript, and K.-U. Fröhlich, D. Gallwitz, M. Hochstrasser, M. Knop, H. Pelham and H.-D. Schmitt for reagents. This study was supported (to S.J.) by the Max Planck Society, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

References

- Biederer T, Volkwein C, Sommer T (1997) Role of Cue1p in ubiquitination and degradation at the ER surface. Science 278: 1806–1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher A, Weissenhorn W (2002) Structural basis for the Golgi membrane recruitment of Sly1p by Sed5p. EMBO J 21: 6114–6124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun S, Matuschewski K, Rape M, Thoms S, Jentsch S (2002) Role of the ubiquitin-selective CDC48(UFD1/NPL4) chaperone (segregase) in ERAD of OLE1 and other substrates. EMBO J 21: 615–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant NJ, James DE (2001) Vps45p stabilizes the syntaxin homologue Tlg2p and positively regulates SNARE complex formation. EMBO J 20: 3380–3388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Ballew N, Barlowe C (1998) Initial docking of ER-derived vesicles requires Uso1p and Ypt1p but is independent of SNARE proteins. EMBO J 17: 2156–2165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu S, DeRisi J, Eisen M, Mulholland J, Botstein D, Brown PO, Herskowitz I (1998) The transcriptional program of sporulation in budding yeast. Science 282: 699–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascher C, Ossig R, Gallwitz D, Schmitt HD (1991) Identification and structure of four yeast genes (SLY) that are able to suppress the functional loss of YPT1, a member of the RAS superfamily. Mol Cell Biol 11: 872–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing TA, Storms RK (1996) Molecular analysis of UFE1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene essential for spore formation and vegetative growth. Curr Genet 30: 396–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison MJ, Hochstrasser M (1991) Epitope-tagged ubiquitin. A new probe for analyzing ubiquitin function. J Biol Chem 266: 21150–21157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick KG, Pelham HR (1992) SED5 encodes a 39-kD integral membrane protein required for vesicular transport between the ER and the Golgi complex. J Cell Biol 119: 513–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemeyer W, Kleinschmidt JA, Saidowsky J, Escher C, Wolf DH (1991) Proteinase yscE, the yeast proteasome/multicatalytic-multifunctional proteinase: mutants unravel its function in stress induced proteolysis and uncover its necessity for cell survival. EMBO J 10: 555–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn R, Scheller RH (2006) SNAREs—engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 631–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop M, Siegers K, Pereira G, Zachariae W, Winsor B, Nasmyth K, Schiebel E (1999) Epitope tagging of yeast genes using a PCR-based strategy: more tags and improved practical routines. Yeast 15: 963–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosodo Y, Noda Y, Adachi H, Yoda K (2002) Binding of Sly1 to Sed5 enhances formation of the yeast early Golgi SNARE complex. J Cell Sci 115: 3683–3691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MJ, Rayner JC, Pelham HR (1997) A novel SNARE complex implicated in vesicle fusion with the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J 16: 3017–3024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Patel S, Latterich M (2001) Regulation of organelle membrane fusion by Pkc1p. Traffic 2: 698–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meusser B, Hirsch C, Jarosch E, Sommer T (2005) ERAD: the long road to destruction. Nat Cell Biol 7: 766–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SK, Indig FE, Olivieri N, Levine ND, Latterich M (1998) Organelle membrane fusion: a novel function for the syntaxin homolog Ufe1p in ER membrane fusion. Cell 92: 611–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng R, Gallwitz D (2002) Sly1 protein bound to Golgi syntaxin Sed5p allows assembly and contributes to specificity of SNARE fusion complexes. J Cell Biol 157: 645–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng R, Gallwitz D (2004) Multiple SNARE interactions of an SM protein: Sed5p/Sly1p binding is dispensable for transport. EMBO J 23: 3939–3949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer T, Jentsch S (1993) A protein translocation defect linked to ubiquitin conjugation at the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 365: 176–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toonen RF, Verhage M (2003) Vesicle trafficking: pleasure and pain from SM genes. Trends Cell Biol 13: 177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toonen RF, de Vries KJ, Zalm R, Sudhof TC, Verhage M (2005) Munc18-1 stabilizes syntaxin 1, but is not essential for syntaxin 1 targeting and SNARE complex formation. J Neurochem 93: 1393–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Dulubova I, Min SW, Chen X, Rizo J, Sudhof TC (2002) Sly1 binds to Golgi and ER syntaxins via a conserved N-terminal peptide motif. Dev Cell 2: 295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures