Abstract

Background and purpose:

Ligand affinity has been a fundamental concept in the field of pharmacology and has traditionally been considered to be constant for a given receptor–ligand interaction. Recent studies have demonstrated that this is not true for all three members of the Gs-coupled β-adrenoceptor family. This study evaluated antagonist affinity measurements at a different Gs-coupled receptor, the histamine H2 receptor, to determine whether antagonist affinity measurements made at a different family of GPCRs were constant.

Experimental approach:

CHO cells stably expressing the human histamine H2 receptor and a CRE-SPAP reporter were used and antagonist affinity was assessed in short-term cAMP assays and longer term CRE gene transcription assays.

Key results:

Nine agonists and seven antagonists, of sufficient potency at the H2 receptor to examine in detail, were identified. Measurements of antagonist affinity were the same regardless of the efficacy of the competing agonist, time of agonist incubation, cellular response measured or presence of a PDE inhibitor.

Conclusions and implications:

Antagonist affinity at the Gs-coupled histamine H2 receptor obeys the accepted dogma for antagonism at GPCRs. This study further confirms that something unusual is indeed happening with the β-adrenoceptors and is not an artefact related to the transfected cell system used. As the human histamine H2 receptor does not behave in a similar manner to any of the human β-adrenoceptors, it is clear that information gathered from one GPCR cannot be simply extrapolated to predict the behaviour of another GPCR. Each GPCR therefore requires careful and detailed evaluation on its own.

Keywords: histamine, GPCR, antagonist, affinity, reporter gene, cAMP

Introduction

Ligand affinity, that is, how well a given ligand binds to a given receptor, has been a fundamental concept in the field of pharmacology. Following the discovery of agonists and the realization that their actions could be manipulated by other drugs, namely antagonists, early pharmacologists, such as Clark, Gaddum and Schild, developed methods to estimate the strength of the drug–receptor binding, that is, antagonist affinity (Rang, 2006 and references therein). It was recognized that different antagonists bound to different receptors with different affinities and thus drugs and receptors were grouped into families, for example, adrenaline, β-blockers and β-adrenoceptors; histamine, antihistamines and histamine receptors. However, some anomalies remained. For example, classical antihistamines did not block all the actions of histamine—although allergic responses were improved, the early antihistamines had no effect on gastric acid secretion (Hill, 1990; Parsons and Ganellin, 2006 and references therein). This led to the idea that receptors could exist in sub-populations and some antagonists could bind to these and others could not (Ash and Schild, 1966). Antagonists to the different subgroups of receptors were then developed and this in turn led to the discovery and definition of the different receptor subtypes (Ash and Schild, 1966; Black et al., 1972; Hill, 1990; Parsons and Ganellin, 2006).

Black and colleagues developed the early selective β-adrenoceptor antagonists (β-blockers) and H2 antihistamines (Black et al., 1965, 1972). They recognized that as a given antagonist binds to a given receptor with the same affinity, the different affinities of the antagonists observed in different tissues was due to the presence of different receptor subtypes, for example, H1, H2 and β1, β2. Since the advent of subtype-selective antagonists, the affinity of the different antagonists to a tissue has been used as the main mechanism to define which subtypes of receptors are present in a given tissue (Hill, 2006).

These discoveries and techniques led to the later development of the many G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) antagonists, which are one of the biggest classes of drugs in clinical use today. All these developments have been based on the premise that the affinity of an antagonist remains constant for a given receptor (Hill, 2006 and references therein). This is because the ability of an antagonist to bind to a given receptor is traditionally considered to be a reflection of the specific chemical interaction between that ligand and the receptor (Kenakin et al., 1995; Hill, 2006). However, more recently, when each member of the Gs-coupled β-adrenoceptor family has been studied in isolation, this has been found not to be the case.

Changes in antagonist affinity were first noted with the β1-adrenoceptor. In recombinant systems expressing only the β1-adrenoceptor, responses to isoprenaline were inhibited by low concentrations of antagonist, whereas much greater concentrations of the same antagonist were required to inhibit agonist responses to CGP 12177 (Pak and Fishman, 1996; Konkar et al., 2000a; Baker et al., 2003a; Baker, 2005a). In a homogenous recombinant system expressing only the β1-adrenoceptor (which has no splice variants), clearly this cannot be explained by the presence of different receptor subtypes. This has been repeated using the β1-adrenoceptor from different species in recombinant systems (for example, Pak and Fishman, 1996; Konkar et al., 2000a), seen in native cells and tissues (including human, Kaumann 1996; Konkar et al., 2000b; Lowe et al., 2002; Lewis et al., 2004) observed in whole animal physiological measurements (Malinowska and Schlicker, 1996; Zakrzeska et al., 2005) and confirmed in knockout animals (Konkar et al., 2000b; Kaumann et al., 1998, 2001). And thus several different values for the antagonist affinity of a single drug can be determined for the β1-adrenoceptor, depending on which drug is used as the competing agonist. This has led to the current view that the β1-adrenoceptor exists in (at least) two different conformations that are activated by different agonists, and antagonists bind to the different conformations with different affinities (Granneman, 2001; Molenaar, 2003).

Similar findings were seen at the human β3-adrenoceptor, suggesting that this receptor also exists in at least two conformations and antagonists bind to these with different affinities (Baker, 2005b). Different antagonist affinities have also been measured at the human β2-adrenoceptor that were once again dependent on which agonist was present. The precise reason for this was unclear but it may be a time-dependent process possibly related to the efficacy of the competing agonist or the phosphorylation state of the receptor (Baker et al., 2003b).

A recent study examining the Gi-coupled human adenosine A1 receptor demonstrated that antagonist affinity measurements appeared constant over a range of responses and different G-protein-coupled states of the receptor (Baker and Hill, 2007). What is unknown therefore is whether the different antagonist affinity measurements seen at the β-adrenoceptors is an unusual property of that particular GPCR family, a property that is common to primarily Gs-coupled receptors, or a more widespread phenomenon across many different GPCRs.

This study therefore evaluated antagonist affinity measurements at the human histamine H2 receptor, to determine whether antagonist affinity measurements made at a different Gs-coupled receptor were indeed constant. The human H2 receptor was chosen because it is another well-studied Gs-coupled GPCR with a large number of different antagonists and many agonists that would allow the question of agonist efficacy to be addressed.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing a cyclic AMP response element-secreted placental alkaline phosphatase (CRE-SPAP) reporter gene were secondarily transfected with the human histamine H2 receptor (DNA from UMR cDNA Resource Centre) using Lipofectamine and OPTIMEM as per the manufacturer's instructions. The transfected cells were selected using resistance to neomycin (1 mg ml−1; for H2 receptor) and hygromycin (200 μg ml−1; for CRE-SPAP reporter gene) for 3 weeks and passaged twice during this period. A single clone (CHO-H2-SPAP cells) was then isolated by dilution cloning. The parent cell line (CHO-SPAP cells) (that is, cells stably expressing the CRE-SPAP reporter gene but no transfected receptor) was also used. All cells were grown and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/nutrient mix F12 containing 10% fetal calf serum and 2 mM L-glutamine in a humidified 5% CO2:95% air atmosphere at 37 °C unless otherwise stated.

CRE-SPAP gene transcription

Cells were grown to confluence in 96-well tissue culture plates. Once confluent, the cells were serum starved by removing the media and replacing it with 100 μl serum-free media (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/nutrient mix F12 containing 2 mM L-glutamine). The cells were then incubated for a further 24 h. Where used, Pertussis toxin (PTX) was added to the serum-free media at a final concentration of 100 ng ml−1 and was thus incubated with the cells for 24 h prior to experimentation. On the day of experimentation, the serum-free media was removed and replaced with 100 μl serum-free media or 100 μl serum-free media containing an antagonist at the final required concentration and the cells were incubated for 1 h. Agonist in 10 μl (diluted in serum-free media) was then added to each well and the cells were incubated for 5 h. After 5 h, the media and drugs were removed, 40 μl serum-free media was added to each well and the cells were incubated for a further 1 h. The plates were then incubated at 65 °C for 30 min to destroy any endogenous phosphatases. The plates were then cooled to 37 °C. 4-Nitrophenyl phosphate (100 μl, 5 mM) in diethanolamine buffer was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37 °C in a normal atmosphere until the yellow colour developed. The plates were then read on a Dynatech MRX plate reader at 405 nm.

In all plates using CHO-H2-SPAP cells, 10 μM histamine was used as a positive control and acted as a standard to compare ligand efficacies. Whenever PTX was used, parallel experiments on cells expressing the Gi-coupled human H3 receptor were also performed to ensure that the PTX prevented Gi-coupled signalling. In all plates using CHO-SPAP cells, 4 μM forskolin was used as a positive control.

3H-cAMP accumulation

Cells were grown to confluence in 24-well plates. The media were removed and the cells pre-labelled for 3 h with 3H-adenine by incubation with 2 μCi ml−1 3H-adenine in serum-free media (0.5 ml per well). The 3H-adenine was removed and each well was washed by the addition and removal of 1 ml serum-free media. Serum-free media (1 ml) containing 100 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) with or without the final required concentration of antagonist were added to each well and the cells were incubated for 30 min. Agonist (in 10 μl serum-free media) was added to each well and the plates were incubated for 30 min. When the intrinsic activity of the antagonists was assessed (for example, Figure 6), the ligands were incubated for 5 h in the presence of 100 μM IBMX to maximize the changes in 3H-cAMP accumulation. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 50 μl concentrated HCl per well. The plates were then frozen, thawed and 3H-cAMP was separated from other 3H-nucleotides by sequential Dowex and alumina column chromatography, as previously described (Donaldson et al., 1988).

In all plates of CHO-H2-SPAP cells, 10 μM histamine was used as a positive control and acted as a standard to compare ligand efficacies. In all plates using CHO-SPAP cells 10 μM forskolin was used as a positive control.

Data analysis

Sigmoidal agonist concentration–response curves were fitted to the data using the following equation through computer-assisted nonlinear regression using the program Graphpad Prism 2:

|

where Emax is the maximal response, [A] is the agonist concentration and EC50 is the concentration of agonist that produces 50% of the maximal response.

Antagonist KD values were then calculated from the shift of the agonist concentration–responses in the presence of a fixed concentration of antagonist using the following equation:

|

where DR (dose ratio) is the ratio of the agonist concentration required to stimulate an identical response in the presence and absence of a fixed concentration of antagonist [B].

In experiments where three different fixed concentrations of the same antagonist were used, Schild plots were constructed using the following equation:

These points were then fitted to a straight line. A slope of 1 then indicates competitive antagonism (Arunlakshana and Schild, 1959).

In Figure 5a, the concentration–response curve is best fitted to a two-component response, the following equation was used:

where N is the percentage of site 1, [A] is the concentration of agonist and EC150 and EC250 are the respective EC50 values for the two agonist sites.

All data are presented as mean±s.e.mean of triplicate determinations and n in the text refers to the number of separate experiments.

Materials

4-Methylhistamine, N-α-methylhistamine, R-α-methylhistamine, S-α-methylhistamine, amthamine, dimaprit, ICI 162846 (N-[1-(4-carboxamidobutyl)-1H-prazol-3-yl)]-N′-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)guanidine), histamine trifluoromethyl toluidide (HTMT), 2-pyridylethylamine, imetit, immepip, impentamine, proxyfan, tiotidine and zolatidine were obtained from Tocris Cookson (Avonmouth, Bristol, UK). Fetal calf serum was from PAA Laboratories (Teddington, Middlesex, UK). PTX was from Calbiochem (Nottingham, UK). 3H-Adenine and 14C-cAMP were from Amersham International (Buckinghamshire, UK). Histamine, cimetidine, nizatidine, ranitidine, famotidine, 1-methylhistamine, 3-methylhistamine, IBMX and forskolin were from Sigma Chemicals (Poole, Dorset, UK) who also supplied all other reagents.

Results

H2 receptor-mediated CRE-SPAP production

Of the many histamine ligands that were screened for agonist activity at the human H2 receptor in the CRE gene transcription assay, nine were found to have significant agonist activity (Table 1). Histamine and N-α-methylhistamine are traditionally considered to be non-selective histamine agonists and amthamine and dimaprit to be H2-selective agonists (Hill et al., 1997). The stereoisomers R-α-methylhistamine and S-α-methylhistamine as well as 4-methylhistamine (originally described to have H2 selectivity, but now considered to be an H4-selective agonist; Lim et al., 2005) were also found to have agonist activity. The H1 agonist 2-pyridylethylamine (Martínez-Mir et al., 1992) also had agonist action at the H2 receptor. HTMT, previously shown to have agonist actions in lymphocytes (Qiu et al., 1990), was also found to have H2 agonist properties. Very similar agonist responses were obtained for all ligands after 24 h pre-incubation with PTX (Table 1). Interestingly, the fold increase over basal was slightly greater following PTX pre-incubation. This probably reflects the removal of the ‘Gi-brake' from endogenous receptors and is similar to that previously seen (Baker and Hill, 2007). For each of these experiments, the response to the Gi-coupled histamine H3 receptor was assessed at the same time to demonstrate the efficacy of the treatment with PTX, and in each case the H3-Gi response was obliterated. Both 1-methylhistamine (log EC50=−4.42±0.05, n=4; after pre-incubation with PTX log EC50=−4.41±0.09, n=3) and 3-methylhistamine (log EC50=−4.66±0.11, n=4; after pre-incubation with PTX log EC50=−4.78±0.05, n=3) were found to have agonist activity. However, the low potency for each of these ligands gave little space for assessing rightward antagonist shifts of the response and they were therefore not investigated further. The H3 agonists imetit, immepip, impentamine and proxyfan had no agonist action at the human H2 receptor.

Table 1.

Log EC50 values and % histamine maximal responses of CRE-SPAP production from CHO-H2-SPAP cells for nine different agonists, in the absence and following 24 h pre-incubation with Pertussis toxin (PTX)

| Agonist | Log EC50 | % histamine | n | +PTX |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log EC50+PTX | % histamine | n | ||||

| Histamine | −7.75±0.04 | 100 | 21 | −7.73±0.07 | 100 | 4 |

| N-α-Methylhistamine | −7.55±0.03 | 107.1±1.37 | 11 | −7.68±0.06 | 90.1±4.9 | 3 |

| Amthamine | −8.10±0.03 | 104.2±1.4 | 14 | −8.26±0.01 | 100.6±0.5 | 3 |

| 4-Methylhistamine | −7.16±0.03 | 103.4±1.8 | 11 | −7.23±0.01 | 103.0±4.4 | 3 |

| Dimaprit | −6.82±0.02 | 93.3±1.6 | 11 | −7.09±0.06 | 96.8±3.4 | 3 |

| R-α-Methylhistamine | −5.53±0.04 | 96.5±2.8 | 10 | −5.55±0.07 | 99.3±1.7 | 3 |

| S-α-Methylhistamine | −5.65±0.04 | 100.1±1.7 | 12 | −5.66±0.06 | 90.4±4.1 | 3 |

| PEA | −5.04±0.04 | 97.6±1.8 | 12 | −5.10±0.04 | 87.1±4.0 | 3 |

| HTMT | −5.26±0.04 | 86.8±2.7 | 12 | −5.28±0.11 | 90.6±4.7 | 3 |

Abbreviations: CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; CRE-SPAP, cyclic AMP response element-secreted placental alkaline phosphatase; HTMT, histamine trifluoromethyl toluidide; PEA, 2-pyridylethylamine.

Values represent mean±s.e.mean of n separate experiments. The response to histamine was 2.63±0.04-fold increase over basal and following PTX pre-incubation was 3.17±0.06-fold over basal.

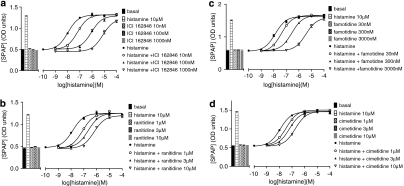

Histamine stimulated a one-component sigmoidal concentration–response curve for CRE-SPAP gene transcription in CHO-H2-SPAP cells that was 2.63±0.04-fold increased over basal (log EC50=−7.75±0.04, n=21; Figure 1a and Table 1). This response was antagonized by ICI 162846 (Wilson et al., 1986) to give a log KD value of −8.67±0.05 (n=19). When a Schild plot was constructed from experiments using three different concentrations of the antagonist, the slope of the line was 1.06±0.04 (n=6), suggesting that the interaction between histamine and ICI 162846 was competitive. When other H2 antagonists were examined, all were found to be competitive antagonists of histamine at the histamine H2 receptor with Schild slopes of 1 (see Figure 1 and Tables 2a and 2b).

Figure 1.

Cyclic AMP response element-secreted placental alkaline phosphatase (CRE-SPAP) gene transcription in response to histamine in the absence and presence of (a) ICI 162846, (b) ranitidine, (c) famotidine and (d) cimetidine in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-H2-SPAP cells. Bars in each graph show basal CRE-SPAP gene transcription, that in response to 10 μM histamine, and that in response to the three different concentrations of antagonist used in each experiment. Data points are mean±s.e.mean of triplicate values from a single experiment and are representative of (a) six, (b) five, (c) five and (d) four separate experiments.

Table 2a.

Log KD values for cimetidine, nizatidine, ranitidine, tiotidine, ICI 162846, famotidine and zolatidine as determined from measurements of CRE-SPAP production from CHO-H2-SPAP cells made in the presence of the nine different agonists

|

Log KD |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cimetidine | n | Nizatidine | n | Ranitidine | n | Tiotidine | n | ICI 162846 | n | Famotidine | n | Zolatidine | n | |

| Histamine | −6.14±0.05 | 15 | −6.92±0.03 | 16 | −6.86±0.03 | 16 | −7.83±0.06 | 16 | −8.67±0.05 | 19 | −7.93±0.03 | 17 | −7.35±0.07 | 16 |

| Nαmh | −6.10±0.04 | 15 | −6.83±0.04 | 15 | −6.85±0.04 | 15 | −7.66±0.06 | 12 | −8.58±0.05 | 15 | −7.94±0.03 | 15 | −7.33±0.06 | 14 |

| Amthamine | −6.04±0.07 | 14 | −6.82±0.04 | 16 | −6.72±0.03 | 15 | −7.57±0.06 | 15 | −8.56±0.05 | 15 | −7.90±0.05 | 15 | −7.24±0.05 | 14 |

| 4-mh | −5.95±0.04 | 12 | −6.72±0.05 | 12 | −6.80±0.03 | 11 | −7.78±0.07 | 12 | −8.91±0.08 | 11 | −7.93±0.05 | 9 | −7.50±0.08 | 12 |

| Dimaprit | −6.14±0.07 | 14 | −6.83±0.04 | 15 | −6.90±0.05 | 15 | −7.69±0.06 | 11 | −8.56±0.07 | 10 | −7.98±0.08 | 11 | −7.31±0.08 | 9 |

| Rαmh | −6.01±0.08 | 5 | −6.90±0.03 | 4 | −6.93±0.07 | 5 | −7.75±0.13 | 6 | −8.60±0.12 | 6 | −7.87±0.08 | 4 | −7.29±0.12 | 5 |

| Sαmh | −5.86±0.07 | 4 | −6.77±0.05 | 5 | −6.82±0.07 | 5 | −7.41±0.10 | 4 | −8.60±0.09 | 7 | −7.95±0.03 | 5 | −7.29±0.10 | 5 |

| PEA | −5.91±0.14 | 3 | −6.96±0.12 | 3 | −6.88±0.10 | 3 | −7.76±0.04 | 3 | −8.70±0.13 | 4 | −7.85±0.09 | 3 | −7.30±0.06 | 5 |

| HTMT | −5.91±0.05 | 5 | −6.86±0.08 | 5 | −6.95±0.05 | 5 | −7.68±0.12 | 5 | −8.68±0.07 | 5 | −8.04±0.13 | 5 | −7.21±0.12 | 5 |

Abbreviations: CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; CRE-SPAP, cyclic AMP response element-secreted placental alkaline phosphatase; HTMT, histamine trifluoromethyl toluidide; 4-mh, 4-methylhistamine; Nαmh, N-α-methylhistamine; Rαmh, R-α-methylhistamine; Sαmh, S-α-methylhistamine; PEA, 2-pyridylethylamine.

Values represent mean±s.e.mean of n separate experiments.

Table 2b.

Slope of the Schild plot from antagonism by cimetidine, nizatidine, ranitidine, tiotidine, ICI 162846, famotidine and zolatidine as determined from measurements of CRE-SPAP production from CHO-H2-SPAP cells made in the presence of the nine different agonists

|

Slope of Schild plot |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cimetidine | n | Nizatidine | n | Ranitidine | n | Tiotidine | n | ICI 162846 | n | Famotidine | n | Zolatidine | n | |

| Histamine | 1.012±0.03 | 4 | 1.04±0.03 | 5 | 1.05±0.05 | 5 | 1.04±0.10 | 5 | 1.06±0.04 | 6 | 1.09±0.02 | 5 | 1.10±0.06 | 4 |

| Nαmh | 1.08±0.06 | 5 | 1.16±0.06 | 5 | 1.06±0.05 | 5 | 1.13±0.10 | 3 | 1.09±0.03 | 5 | 1.01±0.02 | 5 | 1.26±0.03 | 4 |

| Amthamine | 1.05±0.08 | 3 | 1.05±0.07 | 5 | 0.99±0.02 | 5 | 1.07±0.04 | 5 | 1.07±0.04 | 5 | 0.99±0.04 | 5 | 1.05±0.05 | 3 |

| 4-mh | 1.09±0.03 | 4 | 1.13±0.02 | 4 | 1.17±0.01 | 3 | 1.12±0.05 | 4 | a | 3 | 1.10±0.03 | 3 | a | 4 |

| Dimaprit | 0.98±0.05 | 3 | 1.08±0.05 | 5 | 1.18±0.03 | 4 | a | a | a | a | ||||

| Rαmh | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | |||||||

| Sαmh | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | |||||||

| PEA | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | |||||||

| HTMT | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | |||||||

Abbreviations: CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; CRE-SPAP, cyclic AMP response element-secreted placental alkaline phosphatase; HTMT, histamine trifluoromethyl toluidide; 4-mh, 4-methylhistamine; Nαmh, N-α-methylhistamine; Rαmh, R-α-methylhistamine; Sαmh, S-α-methylhistamine; PEA, 2-pyridylethylamine.

Values represent mean±s.e.mean of n separate experiments.

A Schild plot was not constructed because parallel shifts were not obtained––increasing concentrations of the antagonist cause a progressive decrease in maximal agonist responses (see Figure 2).

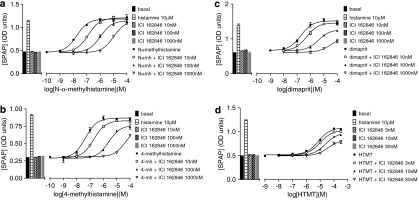

The agonist action of eight other histamine agonists was then examined. Of these most appear as full agonists at the H2 receptor when the response was measured at the level of CRE-SPAP production (Table 1). However, as increasing concentrations of ICI 162846 were used, the maximal responses obtained from 4-methylhistamine, dimaprit, R-α-methylhistamine, S-α-methylhistamine, 2-pyridylethylamine and HTMT decreased and thus the concentration–response curves were flattened (Figure 2). In these cases, it was not possible to construct a Schild plot. Estimations of antagonist log KD value of the antagonist were therefore obtained only from the first or first and second shift of the agonist curve when the maximal response was largely maintained (Tables 2a and 2b). The inhibitory properties of the other antagonists were also examined (Tables 2a and 2b). When, for example, ranitidine was used as the antagonist, less marked decreases in maximal effects were seen (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Cyclic AMP response element-secreted placental alkaline phosphatase (CRE-SPAP) gene transcription in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-H2-SPAP cells in response to (a) N-α-methylhistamine, (b) 4-methylhistamine, (c) dimaprit and (d) histamine trifluoromethyl toluidide (HTMT) in the absence and presence different concentrations of ICI 162846. Bars show basal CRE-SPAP gene transcription, that in response to 10 μM histamine, and that in response to the various concentrations of ICI 162846 alone as used in each experiment. Data points are mean±s.e.mean of triplicate values from single experiments that are representative of (a) five, (b) three, (c) four and (d) five separate experiments.

Figure 3.

Cyclic AMP response element-secreted placental alkaline phosphatase (CRE-SPAP) gene transcription in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-H2-SPAP cells in response to (a) N-α-methylhistamine (Nαmh), (b) 4-methylhistamine (4-mh) and (c) dimaprit in the absence and presence of 1, 3 or 10 μM raniditine and (d) histamine trifluoromethyl toluidide (HTMT) in the absence and presence of 1 μM raniditine. Bars show basal CRE-SPAP gene transcription, that in response to 10 μM histamine, and that in response 1, 3 or 10 μM ranitidine alone. Data points are mean±s.e.mean of triplicate values from single experiments that are representative of (a) five, (b) three, (c) four and (d) five separate experiments.

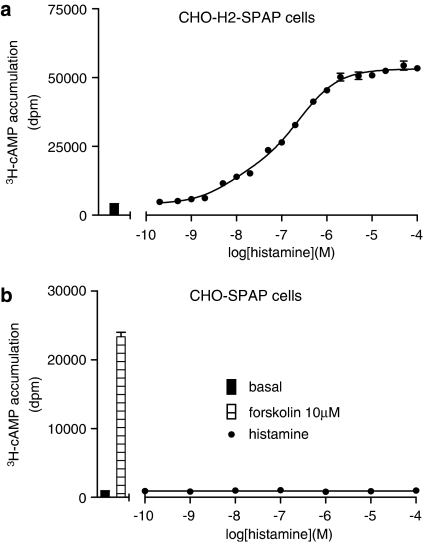

H2 receptor-mediated 3H-cAMP accumulation

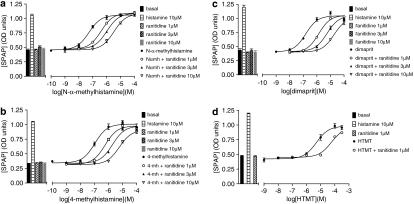

When the same nine agonists were examined in the 3H-cAMP accumulation assay, the partial agonist nature of several ligands was more apparent (Figure 4 and Table 3). When these responses were inhibited by ranitidine and tiotidine, the resulting log KD values were the same as those obtained in the CRE gene transcription assay (Table 4). As even the lowest concentrations of ranitidine and tiotidine required to shift the concentration–response curves of 2-pyridylethylamine or HTMT caused a significant reduction in the maximal response obtained, log KD values for ranitidine and tiotidine in these cases could not be determined.

Figure 4.

3H-cAMP accumulation in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-H2-SPAP cells in response to (a) histamine, (b) N-α-methylhistamine (Nαmh), (c) dimaprit and (d) histamine trifluoromethyl toluidide (HTMT) in the absence and presence of 1 μM ranitidine. Bars show basal 3H-cAMP accumulation, that in response to 10 μM histamine, and that in response to 1 μM ranitidine alone. Data points are mean±s.e.mean of triplicate values from single experiments that are representative of (a) four, (b) four, (c) five, and (d) four separate experiments.

Table 3.

Log EC50 values and % histamine maximal responses of 3H-cAMP accumulation from CHO-H2-SPAP cells for nine different agonists (as determined from a one-component sigmoidal concentration–response curve; 30 min agonist incubations)

| Agonist | Log EC50 | % histamine | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histamine | −7.08±0.10 | 100 | 5 |

| N-α-Methylhistamine | −7.00±0.06 | 104.6±2.2 | 5 |

| Amthamine | −7.61±0.10 | 100.6±1.9 | 5 |

| 4-Methylhistamine | −6.56±0.06 | 106.7±2.2 | 4 |

| Dimaprit | −6.31±0.09 | 98.4±2.8 | 5 |

| R-α-Methylhistamine | −5.08±0.11 | 87.8±2.9 | 5 |

| S-α-Methylhistamine | −5.21±0.06 | 82.0±5.5 | 5 |

| PEA | −5.00±0.03 | 70.3±6.6 | 4 |

| HTMT | −5.13±0.06 | 53.5±2.4 | 6 |

Abbreviations: CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; HTMT, histamine trifluoromethyl toluidide; PEA, 2-pyridylethylamine; SPAP, secreted placental alkaline phosphatase.

Values represent mean±s.e.mean of n separate experiments. The response to histamine was 9.1±1.4-fold over basal.

Table 4.

Log KD values for ranitidine and tiotidine as determined from 3H-cAMP accumulation measurements made in the presence of the nine different agonists

| Agonist | Log KD ranitidine | n | Log KD tiotidine | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histamine | −6.98±0.05 | 4 | −7.90±0.07 | 4 |

| N-α-Methylhistamine | −6.93±0.03 | 4 | −7.78±0.06 | 4 |

| Amthamine | −7.04±0.07 | 4 | −7.84±0.01 | 4 |

| 4-Methylhistamine | −7.01±0.03 | 4 | −7.93±0.05 | 4 |

| Dimaprit | −6.95±0.06 | 5 | −7.91±0.05 | 4 |

| R-α-Methylhistamine | −7.04±0.08a | 4 | −7.92 ±0.04a | 3 |

| S-α-Methylhistamine | −7.01±0.07a | 4 | −7.88±0.10a | 3 |

| PEA | b | 4 | b | 4 |

| HTMT | b | 4 | b | 4 |

Abbreviations: HTMT, histamine trifluoromethyl toluidide; PEA, 2-pyridylethylamine.

Values represent mean±s.e.mean of n separate experiments. There is no statistical difference between any of the log KD values obtained for ranitidine determined in the presence of the different agonists. Likewise there is no difference for the log KD values for tiotidine (P>0.05, ANOVA, Newman–Keuls post hoc).

Estimates of log KD values for antagonists. The log KD value was determined as described in the Materials and methods; however, there was a small reduction in maximum response of the agonist in the presence of the antagonist.

Log KD values were not obtained, as a parallel shift in the presence of antagonist was not obtained (the maximal response to PEA and HTMT was decreased significantly in the presence of antagonists, see Figure 4d).

A more detailed examination of the concentration–response curves to histamine suggests that the concentration–response is best fitted to a two-component curve (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

3H-cAMP accumulation in (a) Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-H2-SPAP and (b) the CHO-SPAP cells (stably expressing the Cyclic AMP response element-secreted placental alkaline phosphatase (CRE-SPAP) reporter but not the transfected receptor) in response to histamine. Bars show basal 3H-cAMP accumulation, that in response to 10 μM forskolin alone. Data points are mean±s.e.mean of triplicate values from a single experiment that is representative of (a) five and (b) four separate experiments. For (a), analysis of the curve fit using the F ratio in Prism 2 to compare the fit of the two-site component concentration–response curve and the traditional one-site sigmoidal concentration–response curve gives a P-value of <0.0001 for the curve fitting best to the two-site component curve.

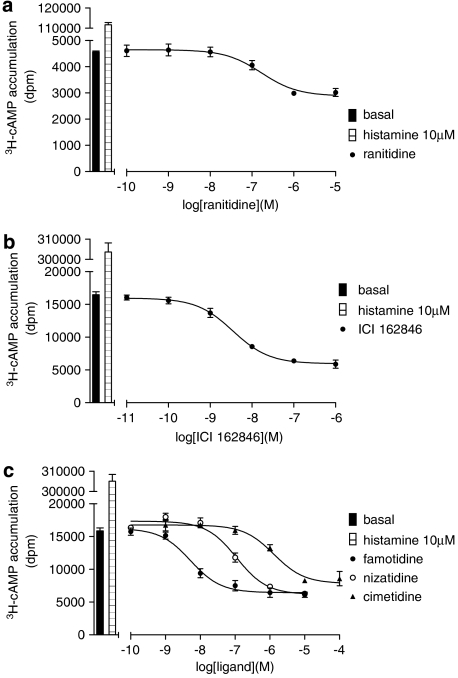

Intrinsic responses of the H2 receptor antagonists

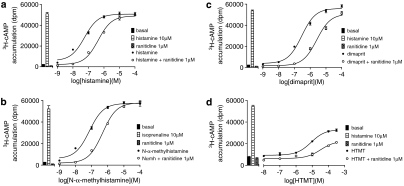

As many H2 antagonists have been reported to be inverse agonists (for example, Smit et al., 1996), the intrinsic properties of these compounds were examined in this cell system. Full concentration–response curves were therefore examined for all the seven antagonists used in this study in both assays. When the gene transcription responses were examined, none of the seven antagonists stimulated a change in CRE gene transcription. However, previous studies have shown that inverse agonism was more difficult to determine in the CRE gene transcription assay than in the 3H-cAMP accumulation assay (for example, Baker et al., 2003c). To maximize changes in 3H-cAMP accumulation, the ligands were incubated for 5 h with each of the antagonists. This confirmed that the antagonist ligands used were inverse agonists (Figure 6 and Table 5).

Figure 6.

3H-cAMP accumulation in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-H2-SPAP cells in response to (a) ranitidine, (b) ICI 162846 and (c) famotidine, nizatidine and cimetidine. Bars show basal 3H-cAMP accumulation, that in response to 10 μM histamine alone. Data points are mean±s.e.mean of triplicate values from a single experiment that is representative of (a) four, (b) three and (c) three separate experiments.

Table 5.

Log IC50 values and % basal responses of 3H-cAMP accumulation from CHO-H2-SPAP cells for seven different antagonists following 5 h ligand incubations

|

Inverse agonism |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Log IC50 | % basal | n | |

| Ranitidine | −6.79±0.06 | 58.2±4.2 | 4 |

| Cimetidine | −6.18±0.08 | 65.9±10.4 | 4 |

| Famotidine | −8.34±0.09 | 50.9±8.3 | 3 |

| ICI 162846 | −8.43±0.05 | 45.4±7.5 | 3 |

| Nizatidine | −7.10±0.06 | 48.8±11.9 | 3 |

| Tiotidine | −7.93±0.14 | 49.6±7.0 | 3 |

| Zolatidine | −7.39±0.10 | 49.2±5.9 | 4 |

Abbreviations: CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; SPAP, secreted placental alkaline phosphatase.

Values represent mean±s.e.mean of n separate experiments.

Lack of gene transcription responses in CHO-SPAP cells

Full, seven-point, concentration–response curves were performed in CHO-SPAP cells (that is, the parent CHO cell line stably expressing the CRE-SPAP reporter but not the human H2 receptor) and examined in the gene transcription assay in an identical manner to that performed in the CHO-H2-SPAP cells for every ligand used in this study (n=3 for each ligand). No gene transcription response was observed at any ligand (to a concentration of 100 μM, except for zolatidine and ICI 162846 where a maximum of 10 μM was used). Therefore, all the CRE-SPAP responses seen in this study were occurring via the transfected human H2 receptor and there was no contribution to the gene transcription response from a native receptor present in the parent cell line. Given the two-component response to histamine in the 3H-cAMP assay, the effects of histamine in the parental cell line were also examined in the 3H-cAMP accumulation assay (n=4). No responses were seen. There is therefore no endogenous receptor contributing to the two-component response to histamine seen in the CHO-H2-SPAP cells.

Discussion and conclusions

Antagonist affinity measurements have traditionally been considered to be constant for a given receptor–ligand interaction and this concept has been a fundamental property in the field of pharmacology. However, recent studies have demonstrated that this is not true for all three members of the β-adrenoceptor family. The β1- and β3-adrenoceptors appear to exist in at least two different conformations or states to which antagonists bind with different affinity (Pak and Fishman, 1996; Konkar et al., 2000a, 2000b; Lowe et al., 2002; Baker et al., 2003a; Baker, 2005a, 2005b). For the β2-adrenoceptor, antagonist affinity appears to vary depending upon the assay used, the time of agonist incubation and the efficacy of the competing agonist (Baker et al., 2003b). This study therefore evaluated antagonist affinity measurements made at the human histamine H2 receptor, in an identical cell background to previous β-adrenoceptor studies, to determine whether antagonist affinity varied in a Gs-coupled receptor from a different family.

Nine ligands were identified to have agonist action at the human histamine H2 receptor in this transfected CRE reporter gene cell system. When examined at the level of 3H-cAMP accumulation, the partial agonist nature of several of the agonists was clear. This is as would be expected from previous studies involving CRE reporter genes, as magnification occurs in the signalling cascade such that for downstream events (for example, CRE gene transcription), partial agonists appear more like full agonists (Baker et al., 2004). Examining the log EC50 values for the two responses, it can be seen that the ligands appear more potent (that is, have a left-shifted log EC50 value) in the CRE gene transcription assay than when measured at the level of 3H-cAMP accumulation. This is by no means a common finding for all GPCRs; for example, the Gi-mediated response from the human adenosine A1 receptor appeared more potent in the cAMP assay (Baker and Hill, 2007), the potencies were identical (except for the very weak partial agonists) in the two assays at the human β3-adrenoceptor (Baker, 2005b), and most catecholamine-site agonists appeared more potent at the β1-adrenoceptor in the CRE gene transcription assay (Baker, 2005a). For the β2-adrenoceptor, efficacious agonists appeared more potent in the cAMP assay, whereas the less efficacious agonists were more potent in the CRE gene transcription assay (Baker et al., 2003b). This was attributed to GRK phosphorylation and internalization of the β2-adrenoceptor, such that exposure to the efficacious agonists caused a desensitization of the response in the long-term downstream assay (January et al., 1997, 1998; Baker et al., 2003b). Changes in agonist potency between assays and between the different GPCRs are therefore likely to be related to different patterns of phosphorylation, internalization and desensitization that occur at different GPCRs (January et al., 1997; Clark et al., 1999).

When the seven antagonists used in this study were examined, they were found to be inverse agonists, in agreement with previous studies (Smit et al., 1996). When examined in the gene transcription assay, the lack of inverse agonist activity was not surprising—there is a much smaller assay window in which to observe responses (after 5 h 3H-cAMP accumulation, histamine stimulated a response of 20- to 30-fold over basal, whereas in the CRE gene transcription assay, the maximal stimulation was 2.6-fold over basal), and inverse agonist activity has previously been reported to be more difficult to determine in the CRE gene transcription system (Baker et al., 2003c).

All antagonists used in this study inhibited the histamine-stimulated gene transcription response in a competitive manner (Schild slope was 1 for all antagonists). The same was true of the other more efficacious agonists, for example, N-α-methylhistamine. However, for some agonists, incubation with increasing concentrations of antagonist resulted in a progressive reduction in the maximum agonist response. This occurred with the less efficacious agonists, where the receptor reserve was minimal or non-existent. Thus in these cases, the majority of receptors were required to be stimulated by the agonist to generate the maximum response. In the presence of an antagonist, the antagonist occupies some of the receptors thereby reducing those available to the agonist and thus the maximal response the agonist was able to generate was reduced. This has previously been seen at other GPCRs (Hopkinson et al., 2000). This effect is therefore greatest with the least efficacious agonists, the ‘stickiest' antagonists (that is, those with the slowest off-rate) and under conditions of non-equilibrium. It was not seen for the very efficacious agonists where so few receptors were required to stimulate a maximal response that even if many were occupied by antagonist, the few remaining would be sufficient for the efficacious agonist to generate a full response.

As would be expected, the agonists identified as partial agonists in the 3H-cAMP accumulation assay correlated well with those for whom a poor receptor reserve was seen in the CRE gene transcription assay. Also, antagonist co-incubation caused more of a decrease in maximum in the agonist responses in the 3H-cAMP accumulation assay, where the shorter incubation time means that less of an equilibrium would have been reached than in the longer term gene transcription assay.

Thus, a study of this nature allows comparison of ligands and the establishment of a rank order for both agonist efficacy and for the ‘stickiness' (that is, those with a slow off-rate) of the antagonists. In this case, histamine and N-α-methylhistamine were the most efficacious agonists and HTMT the least; ICI 162846, zolatidine and tiotidine were the ‘stickiest' antagonists, whereas ranitidine, cimetidine, etc. appeared to have a short duration of action. Furthermore, the affinity of every antagonist measured in the presence of each of the agonists was the same. This means that the efficacy of the competing agonist does not affect the measurements of antagonist affinity at the human histamine H2 receptor.

When antagonist affinities were determined for the upstream short-term response, generation and accumulation of 3H-cAMP, the antagonist affinities were found to be the same regardless of the competing agonist. Furthermore, the log KD values obtained were the same as those obtained in the CRE gene transcription assay.

Therefore, the affinity of every antagonist determined in both the longer term downstream CRE gene transcription assay and the shorter term upstream second messenger assay was the same. Thus, for the histamine H2 receptor (at least with the ligands used in this study), measurements of antagonist affinity follow the accepted dogma and are not dependent on the efficacy of the competing agonist, the level of the functional response measured, the time of agonist incubation or the presence of a phosphodiesterase inhibitor.

A close inspection of the concentration–response relationship for histamine and N-α-methylhistamine (Figures 4a and b) suggests that the concentration–response curve may not be best described by a one-component sigmoidal response curve. A more detailed examination of the concentration–response curves confirms the two-component nature of the response (log EC50: site 1=−8.07±0.16, site 2=−6.65±0.11; 38.2±5.6% site 1 for histamine, n=5; log EC50: site 1=−7.77±0.17, site 2=−6.39±0.09, 46.4±4.3% site 1 for N-α-methylhistamine, n=5; Figure 5). Analysis of the curve fits using the F ratio in Prism 2 shows that the curves fit better to a two-component fit than a one-component fit for every experiment using histamine or N-α-methylhistamine as the agonist. In this study, the differences in the two components are too small to allow a detailed study of antagonist affinity at the two components to be addressed. However, this does offer a tantalizing prospect that maybe ligand interaction at the human histamine H2 receptor is not as straightforward as the rest of the study makes it appear!

This study is therefore in sharp contrast to previous studies involving the human β-adrenoceptors. The recombinant system used in this study was very similar to that used in the previous studies and therefore allow direct comparisons to be made. Several important conclusions can therefore be drawn from this. At least with the drugs used in this study, antagonist affinities at the histamine H2 receptor remain constant regardless of the conditions in which they are measured. The H2 receptor, therefore like the Gi-coupled human adenosine A1 receptor, follows the traditional dogma of pharmacology and importantly, the varying antagonist affinity does not extend to all Gs-coupled receptors.

This also therefore further demonstrates that this recombinant cell system and gene transcription measurements are useful tools to examine GPCR interactions as it can detect both receptors that follow the traditional dogma and those that do not.

In conclusion, therefore, this study further validates that something unusual is indeed happening with the β-adrenoceptors. For the histamine H2 receptor, antagonist affinity measurements are the same regardless of which agonist is used as the competing agonist. Thus, the measurements do not vary with agonist efficacy, time of agonist incubation, response measured or presence of a PDE inhibitor, and this Gs-coupled GPCR obeys the accepted dogma for antagonism at GPCRs. The antagonist affinity measurements do not provide any suggestion of more than one ligand-binding pocket or conformation of the H2 receptor (at least with the ligands used in this study) analogous to that of the β1 and β3 adrenoceptors. This lack of change at the H2 receptor gives further weight to the suggestion that some modification of the β2-adrenoceptor occurs following exposure to different agonists to alter the affinity of antagonists, and this modification is receptor specific, and is not related to the artificial transfected cell system used to study it. As the human histamine H2 receptor does not behave in a manner similar to any of the human β-adrenoceptors, what is clear is that information gathered from one GPCR cannot be simply extrapolated to predict the behaviour of another GPCR. Each GPCR therefore requires careful and detailed evaluation on its own. This study does, however, offer the tantalizing possibility that not all drug interactions may be as simple as they appear, even at what appears to be the most straightforward of receptors, the human histamine H2 receptor (for example, Figure 5).

Acknowledgments

JGB is a Wellcome Trust Clinician Scientist Fellow. I thank Richard Proudman and Javeria Ahmad for their technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- CRE

cyclic AMP response element

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- HTMT

histamine trifluoromethyl toluidide

- ICI 162846

N-[1-(4-carboxamidobutyl)-1H-prazol-3-yl)]-N′-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)guanidine

- PTX

Pertussis toxin

- SPAP

secreted placental alkaline phosphatase

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Arunlakshana O, Schild HO. Some quantitative uses of drug antagonists. Br J Pharmacol. 1959;14:48–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1959.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash ASF, Schild HO. Receptors mediating some actions of histamine. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1966;27:427–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1966.tb01674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG. Sites of action of β-ligands at the human β1-adrenoceptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005a;313:1163–1171. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.082875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG. Evidence for a secondary state of the human β3-adrenoceptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2005b;68:1645–1655. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG, Hall IP, Hill SJ. Agonist actions of ‘β-blockers' provide evidence for two agonist activation sites or conformations of the human β1-adrenoceptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2003a;63:1312–1321. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG, Hall IP, Hill SJ. Influence of agonist efficacy and receptor phosphorylation on antagonist affinity measurements: differences between second messenger and reporter gene responses. Mol Pharmacol. 2003b;64:679–688. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG, Hall IP, Hill SJ. Agonist and inverse agonist actions of ‘β-blockers' at the human β2-adrenoceptor provide evidence for agonist-directed signalling. Mol Pharmacol. 2003c;64:1357–1369. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.6.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG, Hall IP, Hill SJ. Temporal characteristics of CRE-mediated gene transcription: requirement for sustained cAMP production. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:986–998. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.4.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG, Hill SJ. A comparison of the antagonist affinities for the Gi and Gs-coupled states of the human adenosine A1 receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:218–228. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.113589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JW, Duncan WA, Durant CJ, Ganellin CR, Parsons ME. Definition and antagonism of histamine H2-receptors. Nature. 1972;236:385–390. doi: 10.1038/236385a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JW, Duncan WAM, Shanks RG. Comparison of some properties of pronethalol and propranolol. Br J Pharmacol. 1965;25:577–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1965.tb01782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RB, Knoll BJ, Barber R. Partial agonists and G-protein coupled receptor desensitization. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:279–286. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson J, Brown AM, Hill SJ. Influence of rolipram on the cyclic-3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate response to histamine and adenosine in slices of guinea-pig cerebral cortex. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:715–723. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granneman JG. The putative beta4-adrenergic receptor is a novel state of the beta1-adrenergic receptor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280:E199–E202. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.2.E199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SJ. Distribution, properties and functional responses of the three classes of histamine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1990;42:45–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SJ. G protein-coupled receptors: past, present and future. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:S27–S37. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SJ, Ganellin CR, Timmerman H, Schwartz JC, Shankley NP, Young JM, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XIII. Classification of histamine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1997;49:253–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson HE, Latif ML, Hill SJ. Non-competitive antagonism of β2-agonist-mediated cyclic AMP accumulation by ICI 118551 in BC3H1 cells endogenously expressing constitutively active β2-adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:124–130. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- January B, Seibold A, Allal C, Whaley B, Knoll BJ, Moore RH, et al. Salmeterol-induced desensitization, internalization and phosphorylation of the human β2-adrenoceptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:701–711. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- January B, Seibold A, Whaley B, Hipkin RW, Lin D, Schonbrunn A, et al. 2-Adrenergic receptor desensitization, internalization and phosphorylation in response to full and partial agonists. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23871–23879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann AJ. CGP 12177 induced increase of human atrial contraction through a putative third beta-adrenoceptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann AJ, Engelhardt S, Hein L, Molenaar P, Lohse M. Abolition of (−)-CGP 12177-evoked cardiostimulation in double beta1/beta2-adrenoceptor knockout mice. Obligatory role of beta1-adrenoceptors for putative beta4-adrenoceptor pharmacology. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;363:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s002100000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann AJ, Preitner F, Sarsero D, Molenaar P, Revelli JP, Giacobino JP. CGP 12177 causes cardiostimulation and binds to cardiac putative beta 4-adrenoceptors in both wild-type and beta 3-adrenoceptor knockout mice. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:670–675. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T, Morgan P, Lutz M. On the importance of the ‘antagonist assumption' to how receptors express themselves. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:17–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00137-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkar AA, Zhu Z, Granneman JG. Aryloxypropanolamine and catecholamine ligand interactions with the β1-adrenergic receptor: evidence for interaction with distinct conformations of β1-adrenergic receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000a;294:923–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkar AA, Zhai Y, Granneman JG. Beta1-adrenergic receptors mediate beta3-adrenergic-independent effects of CGP 12177 in brown adipose tissue. Mol Pharmacol. 2000b;57:252–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CJ, Gong H, Brown MJ, Harding SE. Overexpression of beta 1-adrenoceptors in adult rat ventricular myocytes enhances CGP 12177A cardiostimulation: implications for ‘putative' beta 4-adrenoceptor pharmacology. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:813–824. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HD, van Rijn RM, Ling P, Bakker RA, Thurmond RL, Leurs R. Evaluation of histamine H1-, H2-, and H3-receptor ligands at the human histamine H4 receptor: identification of 4-methylhistamine as the first potent and selective H4 receptor agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1310–1321. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.087965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe MD, Lynham JA, Grace AA, Kaumann AJ. Comparison of the affinity of β-blockers for the two states of the β1-adrenoceptor in ferret ventricular myocardium. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:451–461. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinowska B, Schlicker E. Mediation of the positive chronotropic effect of CGP 12177 and cyanopindolol in the pithed rat by atypical beta-adrenoceptors, different from beta 3-adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:943–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Mir MI, Estañ L, Morales-Olivas FJ, Rubio E. Effect of histamine and histamine analogues on human isolated myometrial strips. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;107:528–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb12778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar P. The ‘state′' of beta-adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:1–2. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak MD, Fishman PH. Anomalous behaviour of CGP 12177A on beta 1-adrenergic receptors. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 1996;16:1–23. doi: 10.3109/10799899609039938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons ME, Ganellin CR. Histamine and its receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:S127–S135. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu R, Melmon KL, Khan MM. Effects of histamine-trifluoromethyl-toluidide derivative (HTMT) on intracellular calcium in human lymphocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;253:1245–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rang HP. The receptor concept: pharmacology's big idea. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:S9–S16. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit MJ, Leurs R, Alewijnse AE, Blauw J, Van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Van De Vrede Y, et al. Inverse agonism of histamine H2 antagonist accounts for upregulation of spontaneously active histamine H2 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6802–6807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JA, Johnston DA, Penston J, Wormsley KG. Inhibition of human gastric secretion by ICI 162,846––a new histamine H2-receptor antagonist. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1986;21:685–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1986.tb05234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakrzeska A, Schlicker E, Kwolek G, Kozłowska H, Malinowska B. Positive inotropic and lusitropic effects mediated via the low-affinity state of beta1-adrenoceptors in pithed rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:760–768. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]