Abstract

Background and purpose:

Chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 may mediate influx of neutrophils in models of acute and chronic inflammation. The potential benefits of oral administration of a CXCR1/2 inhibitor, DF 2162, in adjuvant-induced polyarthritis (AIA) were investigated.

Experimental approach:

A model of AIA in rats was used to compare the therapeutic effects of the treatment with DF2162, anti-TNF or anti-CINC-1 antibodies on joint inflammation and local production of cytokines and chemokines.

Key results:

DF2162 prevented chemotaxis of rat and human neutrophils induced by chemokines acting on CXCR1/2. DF2162 was orally bioavailable and metabolized to two major metabolites. Only metabolite 1 retained CXCR1/2 blocking activity. Treatment with DF2162 (15 mg kg−1, twice daily) or metabolite 1, but not metabolite 2, starting on day 10 after arthritis induction diminished histological score, the increase in paw volume, neutrophil influx and local production of TNF, IL-1β, CCL2 and CCL5. The effects of DF2162 were similar to those of anti-TNF, and more effective than those of anti-CINC-1, antibodies. DF2162 prevented disease progression even when started 13 days after arthritis induction.

Conclusions and implications:

DF 2162, a novel orally-active non-competitive allosteric inhibitor of CXCR1 and CXCR2, significantly ameliorates AIA in rats, an effect quantitatively and qualitatively similar to those of anti-TNF antibody treatment. These findings highlight the contribution of CXCR2 in the pathophysiology of AIA and suggest that blockade of CXCR1/2 may be a valid therapeutic target for further studies aiming at the development of new drugs for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Keywords: chemokine receptor, CXCR2, experimental arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, neutrophil, TNF-α

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis is a common chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the infiltration of monocytes, T cells and neutrophils into several joints (Olsen and Stein, 2004; Firestein, 2006; Garrood and Pitzalis, 2006). In the joints, leukocytes interact with resident cells and matrix and produce several mediators of inflammation, degradative enzymes and oxygen species, all of which may injure the tissue (Olsen and Stein, 2004; Firestein, 2006; Palmer et al., 2006). Chemokines are relatively small proteins (8–10 kDa) that direct the recruitment of leukocytes from the blood stream to the extravascular tissues. Four different subfamilies of chemokines and chemokine receptors have been identified: CC, CXC, CX3C and C (Murphy et al., 2000; Pease and Williams, 2006). Chemokines are produced in a coordinated and controlled manner during inflammation and act on receptors that are differentially expressed on leukocyte subsets (Murphy et al., 2000; Gerard and Rollins, 2001; Pease and Williams, 2006). The blockade of chemokine receptors may represent an interesting possibility in the development of novel drugs for the treatment of inflammatory diseases (Bizzarri et al., 2006; Pease and Williams, 2006; Wells et al., 2006).

There are data supporting a role for the chemokine system in mediating leukocyte infiltration and chronic tissue damage in animal models of arthritis that mimic some aspects of human rheumatoid arthritis. For example, the chemokine CCL5 (RANTES) and its receptors CCR1 and CCR5 are expressed in the joints of rats with adjuvant-induced arthritis (AIA; Shahrara et al., 2003, 2005; Haas et al., 2005). More importantly, blockade of these receptors with met-RANTES ameliorates AIA in rats (Shahrara et al., 2005). Another group of chemokines that may also be of interest in the setting of arthritis are the CXC chemokines, and specifically CXC chemokines that act on CXCR1 and CXCR2. The latter receptors are expressed on activated T lymphocytes and, especially, on neutrophils (Murphy et al., 2000; Pease and Williams, 2006). Blockade of CXCR1/2 or blockade of chemokines, which act on these receptors, such as CXCL8 (interleukin-8 (IL-8)), have been shown to prevent neutrophil influx and tissue injury in several models of acute and chronic inflammation (Gerard and Rollins, 2001; Kasama et al., 2005; Bizzarri et al., 2006; Wells et al., 2006). The possible role of CXC chemokines in the pathophysiology of experimental arthritis has received relatively less attention. It has been shown that CXCL8 is detectable in synovial fluid of patients with active disease and in joints of animals injected with monosodium urate crystals or lipopolysaccharide (Nishimura et al., 1997; Matsukawa et al., 1999; Murphy et al., 2000). On the basis of these findings, anti-IL-8 antibodies have been tested in patients with rheumatoid arthritis but not found to have any significant effect (reviewed by Bizzarri et al., 2006; Wells et al., 2006). There still remains the possibility that other chemokines acting on CXCR1/2, such as CXCL1 and CXCL2, may still be unopposed after anti-CXCL8 treatment and still be capable of inducing neutrophil influx and arthritis. A single study has determined the effects of a low molecular weight, non-peptide CXCR2 receptor antagonist in a model of arthritis in rabbits (Podolin et al., 2002). In these animals, the molecule had a significant effect on neutrophil influx at day 15 and TNF-α production at 24 h in a model of antigen-induced arthritis (Podolin et al., 2002).

There are compounds that provide symptomatic relief of arthritis, including paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and low-dose steroids. There are also drugs that have some disease-modifying properties, including gold and chloroquine. These are relatively safe drugs but do not appear to modify significantly the fundamental pathological processes responsible for chronic inflammation (Olsen and Stein, 2004). Cytokine-based therapies, especially anti-tumour-necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) antibodies or the soluble TNF-α receptor 1, have been used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and found to be useful in preventing progression of chronic arthritis in groups of patients. However, these therapies do not benefit all patients and entail the use of exogenous proteins (such as antibodies), which are costly to produce, require administration by injection or infusion and have the inherent possibility of an immune response against the exogenous protein (Olsen and Stein, 2004).

We have recently described a class of derivatives of 2-arylphenylpropionic acids, which are effective, non-competitive, allosteric inhibitors of the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 (Bertini et al., 2004; Souza et al., 2004; Bizzarri et al., 2006). In the present study, we have made use of 2-arylphenylpropionic acid derivatives to evaluate the potential of developing inhibitors of CXCR1 and CXCR2 for the treatment of arthritis. To this end, we evaluated the effects of the CXCR1/2 inhibitor DF 2162 (Figure 1a) in a model of AIA in rats and compared the effects of the compound with those provided by treatment of animal antibodies against TNF-α or the rat homologue of human CXCL1 (cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-1 (CINC-1)).

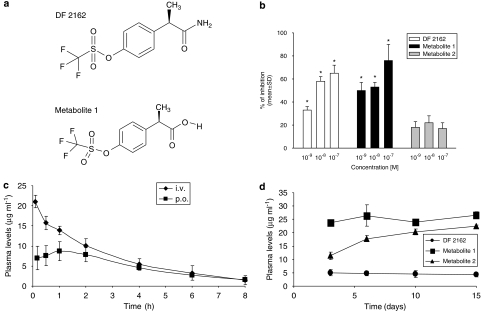

Figure 1.

Chemical structure, pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profile of DF 2162 in rats. The chemical structures of DF 2162 and metabolite 1 are shown in (a). In (b), the inhibitory effects of DF 2162 and its two major metabolites against CINC-1 (2.5 nM)-induced neutrophil chemotaxis are shown. Only DF 2162 and metabolite 1 significantly (P<0.05) inhibited neutrophil chemotaxis. Plasma levels after single i.v. or p.o. administration of DF 2162 (15 mg kg−1) are shown in (c). The steady-state concentrations of DF 2162 (15 mg kg−1, twice daily) are shown in (d). In all experiments, there were five animals in each group, with the exception of (b) where results are expressed as percentage of inhibition of chemokine-induced chemotaxis from at least three experiments (6–18 replicates). *P<0.01 compared to CINC-1-induced chemotaxis.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (in Brazil) or conformed to institutional guidelines (in Italy) and were in compliance with national (D.L. no. 116, G.U. suppl. 40; 18 February 1992) and international regulations (EEC Council Directive 86/609, OJ L 358, 1; 12 December 1987; NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, US National Research Council, 1996).

Female Holtzman rats (140–170 g) were used throughout this study, except for the pharmacokinetic studies (see below). Animals were kept in cages (maximum of six animals per cage) at a room with controlled temperature (23° C) and on a 12-h light–dark cycle. Water and food were provided ad libitum. Animals were purchased from the animal facility of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais and kept at the animal room of the laboratory after arthritis induction. For the pharmacokinetic studies, experiments were carried out in male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–250 g).

Human and rat neutrophil chemotaxis

Cell migration of human PMN and peritoneal elicited rodent PMN was evaluated using a 48-well microchemotaxis chamber, as previously described (Falk et al., 1980). Rat PMN were elicited in the peritoneal cavity by injecting 5% glycogen. Cell suspensions (1.5–3 × 106 cells ml−1) were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min in the presence of vehicle or of indicated concentrations of DF 2162, metabolite 1, metabolite 2 or reparixin (also called repertaxin; all from Dompé pha.r.ma) and then placed, in triplicate, in the upper compartment of the chemotactic chamber. Different agonists were placed in the lower compartment of the chamber at the following concentrations: 1 nM CXCL8, 10 nM CXCL1 and 2.5 nM CINC-1. The two compartments of the chemotactic chamber were separated by a 5-μm PVP-free polycarbonate filter. The chemotactic chamber was incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere for 45 min (human PMN) or 1 h (rodent PMN). At the end of incubation, the filter was removed, fixed, stained with Diff-Quik (according to the supplied instructions) and five oil immersion fields at high magnification ( × 100) were counted for each migration well after sample coding.

Pharmacokinetic studies

After in vivo administration, DF 2162 is transformed into two major metabolites (unpublished data on file Dompé pha.r.ma), referred to as metabolites 1 and 2 in the present paper. The pharmacokinetic profile of DF 2162 was evaluated after single p.o. (15 mg kg−1) or i.v. (15 mg kg−1) administration of the compounds to male Sprague–Dawley rats. Metabolites 1 and 2 were given orally at the doses of 3 and 12 mg kg−1, respectively. Venous blood samples (0.15 ml) were collected (tail vein) at different times (5, 30 min, 1, 2, 4, 6 and 8 h) after i.v. and p.o. administration of the compounds. The blood volume withdrawn has been shown not to cause significant disturbance to the normal physiology of the animals (Diehl et al., 2001). The plasma levels of metabolites were also measured at 5, 6, 10 and 15 days after p.o. treatment with DF 2162 for 15 days (15 mg kg−1 twice daily).

To obtain the pharmacokinetic profile of the compounds, plasma samples were analysed by a validated HPLC method (Garau et al., 2006). Pharmacokinetic analysis was performed on the concentration–time profiles of DF 2162, metabolites 1 and 2 in rat plasma with non-compartmental analysis using the Kinetica Version 4.4 software. The main pharmacokinetic parameters considered were plasma concentration at time zero (C0), area under the curve (AUCtot), half-life (t1/2), total body clearance (CL), steady-state distribution volume (Vss) and p.o. bioavailability (F).

Induction of arthritis by adjuvant

For the induction of arthritis, animals were anaesthetized i.p. with a ketamine and xylazine mixture (3.2 and 0.16 mg kg−1, respectively) and then injected subcutaneously with a single dose of 0.2-ml mineral oil–water emulsion (10:1, v/v) containing 400 μg of dried Mycobacterium butyricum into the dorsal root of the tail, as previously described (Francischi et al., 2000). Control animals were those injected subcutaneously with a single dose of 0.2-ml mineral oil–water emulsion (10:1) without M. butyricum in the same location. The time of adjuvant injection is referred to as day 0.

Treatment schedules

DF 2162 and its metabolites 1 and 2 were synthesized in the laboratories of Dompé pha.r.ma. The compounds were suspended in an aqueous solution of carboxymethylcellulose (0.5% w/v). Control arthritic animals received the vehicle only. Preliminary experiments using the chemokine CINC-1 (Peprotech, Veracruz, Mexico) were used to determine the optimal dose of DF 2162 (data not shown). DF 2162 (7, 15, 30 mg kg−1, twice daily), its metabolites (3 and 12 mg kg−1, twice daily, respectively, for metabolites 1 and 2) or vehicle were administered via oral gavage. Treatment was initiated on day 10 after arthritis induction, when the first signs of joint inflammation are usually noted (Francischi et al., 2000; Barsante et al., 2005) and maintained until day 15. On day 16, the animals were killed for histopathological, biochemical and cytokine analyses. In a few animals, treatment was started on day 13, closer to the peak of arthritis in AIA rats (established arthritis) and maintained until day 15 or 20.

For the treatment with antibodies, animals were given anti-TNF-α or anti-CINC-1 polyclonal antibodies raised in sheep (5 ml of anti-serum kg−1, s.c.) on days 10 and 13 after arthritis induction. These antibodies, used at these doses, have been shown to prevent the action of the respective chemokines in an effective and selective manner (Souza et al., 2001, 2004; Lorenzetti et al., 2002). Control animals received non-immune sheep serum.

Measurement of oedema

Hind-paw volume was used as an indicator of paw oedema and was measured daily using an Ugo Basile hydroplethysmometer (model 7150). Results are reported as changes in paw volume (ml). All measurements were obtained at the same time of the day.

Histopathological processing and analysis

Arthritic paws were collected 16 days after the induction of arthritis and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. The fragments were then treated with a 10% nitric acid solution for decalcification, dehydrated, cleared and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections of the whole paw were cut (3 μm thick), stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined for the degree of synovitis and bone destruction by one of the authors (WT), without knowledge of the treatments. The following variables were assessed histologically: oedema, synovial inflammation, bone and cartilage erosion and accumulation of neutrophils. Animals then received a semi-quantitative score ranging from 0 to 3 (0=no erosion, 3=extensive erosion, oedema, cellular infiltration and bone destruction) depending on the intensity of the findings observed. The tibiotarsal joints of four animals were observed in each experimental group.

Measurement of inflammatory mediators in tissue

For the measurement of tissue cytokine and chemokine level, the subcutaneous tissue of the right hind paw and tissue surrounding the tibiotarsal joints were removed and placed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 0.1 mM benzethonium chloride, 10 mM EDTA and 20 kallikrein international units of aprotinin A. The tissue was homogenized, centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min and stored at −70 °C until further analysis. The levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, CCL5 (RANTES) and CCL2 (MCP-1) were evaluated using sandwich ELISA. ELISA kits for TNF-α and IL-1β were from the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (Potters Bar, UK) and antibody pairs for CCL5 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) and CCL2 (Peprotech, Veracruz, Mexico) were obtained commercially and used according to the instructions supplied by the manufacturer.

Determination of myeloperoxidase activity

The extent of neutrophil accumulation in the hind paw was measured by assaying myeloperoxidase activity, as previously described (Matos et al., 1999). Using the conditions described below, the methodology is very selective for the determination of neutrophils over macrophages (Barcelos et al., 2005). Briefly, the left hind-paw tissue was removed and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Upon thawing, the tissue (0.1 g of tissue per 1.9 ml buffer) was homogenized in pH 4.7 buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 0.2 M NaPO4 and 0.015 M NaEDTA), centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min and the pellet subjected to hypotonic lysis (1.5 ml of 0.2% NaCl solution followed 30 s later by addition of an equal volume of a solution containing NaCl 1.6% and glucose 5%). After a further centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 0.05 M NaPO4 buffer (pH 5.4) containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HTAB) and rehomogenized. Aliquots (1 ml) of the suspension were transferred into 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes followed by three freeze–thaw cycles using liquid nitrogen. The aliquots were then centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 g, the pellet was resuspended to a volume of 1 ml and samples of hind paw were assayed. Myeloperoxidase activity in the resuspended pellet was assayed by measuring the change in optical density at 450 nm using tetramethylbenzidine (1.6 mM) and H2O2 (0.5 mM). Results were expressed as ‘myeloperoxidase index' and were calculated by comparing the optical density of hind-paw tissue supernatant with a standard curve of neutrophil (>95% purity) numbers.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean±s.e.mean (or mean±s.d. for chemotaxis and pharmacokinetic data) of the shown number of experiments. For experiments evaluating effect of drugs on paw volume, the area under the curve was calculated and used to assess differences between groups. Results were analysed using analysis of variance and Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test. Values that were not normally distributed were log transformed prior to the application of the parametric tests. P-values <0.05 were considered significant. Histological evaluations are presented as medians (with interquartile ranges) and were evaluated using Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn's post hoc test. All tests were carried out using Graph Prism Software (Version 3.0).

Results

Pharmacological analysis of DF 2162 and its metabolites

DF 2162 {4-[(1R)-2-amino-1-methyl-2-oxoethyl]phenyl trifluoromethanesulphonate} (Figure 1a) is a novel lead compound derived from a molecular modelling-driven structure–activity relationship study that led to the identification of a new class of non-competitive, allosteric inhibitors of CXCR1/2 to which reparixin belongs (Bertini et al., 2004). DF 2162 potently blocked both the human CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors, as demonstrated by the ability of the compound to inhibit the chemotaxis of neutrophils induced by CXCL8 (mainly an agonist at CXCR1) and CXCL1 (an agonist at CXCR2) with a 10-fold difference (see Table 1). In the same conditions, reparixin was found to have greater than 400-fold selectivity for CXCR1 over CXCR2 (Bertini et al., 2004). DF 2162 also effectively prevented the in vitro chemotactic effects of CINC-1 on rat neutrophils (Table 1; Figure 1b).

Table 1.

Inhibitory effects of reparixin, DF 2162 and its metabolites 1 and 2 on the chemotaxis of human and rat neutrophils

|

IC50 for neutrophil chemotaxis (nM) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Agonists |

Reparixin |

DF 2162 |

Metabolite 1 |

Metabolite 2 |

| Species | |||||

| Human neutrophils | CXCL8 | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | >1000 |

| CXCL1 | 400 | 10 | 2 | >1000 | |

| Rat neutrophils | CINC-1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | >1000 |

Human or rat cell migration was induced by the indicated chemokines in the absence or presence of reparixin, DF 2162, metabolites 1 and 2 (0.1 nM–1 μM). Results, expressed as percentage of inhibition of chemokine-induced chemotaxis, from at least three experiments (6–18 replicates) were used to calculate IC50 values.

DF 2162 showed long-lasting activity after p.o. administration. The main pharmacokinetic parameters obtained after administration of DF 2162 are given in Table 2. After i.v. injection, the plasma concentration of DF 2162 declined according to a mono-exponential model. After p.o. administration, the pharmacokinetic profile indicated a rapid absorption of DF 2162. The maximum concentration (Cmax) in plasma was reached at 42 min after administration and the bioavailability of the compound following p.o. administration in fasted animals was 72% (Figure 1c; Table 2).

Table 2.

Main pharmacokinetic parameters of DF 2162 and its major metabolites, metabolites 1 and 2, in male rats after administration of a single i.v. or p.o. dose

| Parameter | Units |

DF 2162 |

Metabolite 1 | Metabolite 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i.v. | p.o. | i.v. | i.v. | ||

| C0 | μg ml−1 | 19.9±1.1 | — | 96.9±7.0 | 17.0±1.1 |

| Cmax | μg ml−1 | — | 8.8±2.4 | — | — |

| tmax | h | — | 0.7±0.4 | — | — |

| AUCtot | h μg ml−1 | 63.4±16.8 | 45.7±6.5 | 2212±356 | 358±23 |

| t1/2 | h | 2.2±0.8 | — | 27.1±4.8 | 25.3±3.2 |

| CL | ml h−1 kg-1 | 247.7±55.8 | — | 6.9±1.1 | 39.0±2.3 |

| Vss | ml kg−1 | 716±57 | — | 258±37 | 1333±160 |

| F | % | — | 72 | 100 | 85 |

Abbreviations: AUCtot, area under the curve; C0, plasma concentration at time zero; Cmax, maximum concentration; CL, total body clearance; F, oral bioavailability; t1/2, half-life; Vss, steady-state distribution volume; tmax, time at which maximal plasma concentration is achieved.

DF 2162 was given at the dose of 15 mg kg-1. Metabolites 1 and 2 were given at doses 3 and 12 mg kg-1, respectively. Data are mean±s.d. of four rats.

DF 2162 is metabolized into two main metabolites—metabolites 1 and 2. Metabolite 1 (Figure 1a) retained the ability of DF 2162 to block the action of both CXCL1 and CXCL8 on human neutrophils and was slightly more potent than DF 2162 (Table 1). Metabolite 2 failed to affect the chemotaxis of neutrophils induced by both chemokines. Consistently, metabolite 1, but not metabolite 2, prevented the chemotaxis of rat neutrophils induced by CINC-1 (Figure 1b). The levels of these metabolites after repeated p.o. administration of DF 2162 (15 mg kg−1 twice daily) are shown in Figure 1d. Pharmacokinetic analysis showed that metabolite 1 was very slowly eliminated and virtually completely absorbed (Table 2). Metabolite 2 had a relatively higher distribution, was very slowly eliminated and 85% was absorbed after p.o. administration (Table 2).

Treatment with DF 2162 ameliorates AIA in rats

Induction of AIA in rats induced a parallel increase in the levels of MPO, an index of neutrophil influx, and of the CXCR1/2-acting chemokine CINC-1 (the rat homologue of human GRO-α; data not shown), justifying an evaluation of the importance of CXCR1/2 in rat AIA.

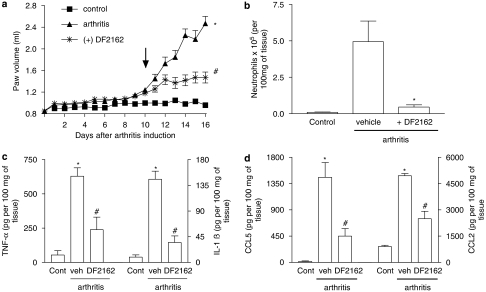

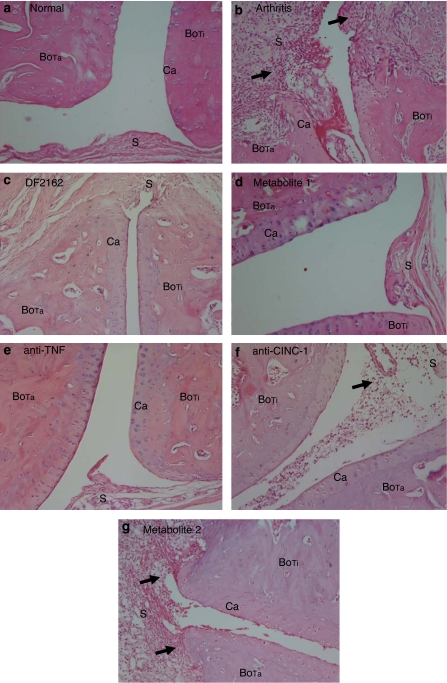

The effects of the treatment with DF 2162 starting from day 10 on AIA are shown in Figure 2. At a dose (15 mg kg−1, twice daily) found to optimally reduce the actions of CINC-1 in rats (data not shown), DF 2162 significantly reduced the increase of paw volume observed in arthritic rats (Figure 2a). This was associated with inhibition of neutrophil influx, as assessed by the measurement of MPO levels (Figure 2b). The histopathological evaluation concurred with the previous findings. In arthritic animals, the articular cavity was larger and there was a marked leukocyte infiltration into the knee joint and surrounding tissues. Neutrophils were found infiltrating the synovium, and there was clear bone and cartilage erosion. At times, bone destruction by the expanded synovial pannus was so intense that there was loss of tissue architecture (Figure 3b). Treatment with DF 2162 resulted in inhibition of the inflammatory changes, including neutrophil influx (Figure 3c). A mild degree of inflammation was still apparent compared to non-arthritic animals (Figure 3a). Semi-quantitative pathological analysis concurred with the quantification of oedema (arthritis, 3 (0); arthritis treated with DF 2162, 1 (1), n=4 in each group, P<0.05, data shown as median (interquartile range)). Inhibition of the increase in paw volume and histological changes were already observed when DF 2162 was used at the dose of 7 mg kg−1 twice daily (data not shown). The levels of the cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β and the chemokines CCL2 and CCL5 were increased at day 16 in animals with AIA. Treatment with DF 2162 prevented the arthritis-associated increase of cytokine levels by 60% or more (Figures 2c–d).

Figure 2.

Effects of treatment with DF 2162 in a model of adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. Treatment with DF 2162 (15 mg kg−1, twice daily) from day 10 after induction of disease (see arrow) inhibited the increase (a) in paw volume, (b) neutrophil influx, and local production of (c) TNF-α, IL-1β and (d) the chemokines CCL5 and CCL2. Results are mean±s.e.m. of six animals in each arthritic group and five non-arthritic animals. *P<0.01 compared to non-arthritic animals (control (cont)); #P<0.01 compared to vehicle-treated arthritic (vehicle (veh)) rats. For experiments in (a), comparisons were made between areas under the curve.

Figure 3.

Effects of the treatment with DF 2162, metabolite 1, metabolite 2, anti-TNF-α or anti-CINC-1 in a model of adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. Representative photographs of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections ( × 200) of tibiotarsal joints of arthritic animals at day 16 after arthritis induction. Note the marked inflammatory infiltrate (arrows) and tissue destruction in vehicle-treated animals (b, arthritis) when compared to non-arthritic animals (a). Also note the beneficial effects of the treatment with DF 2162 (c), metabolite 1 (d) and anti-TNF-α antibody (e). Treatment with anti-CINC-1 (f) and metabolite 2 (g) were less effective. See the text for detailed description of the effects of the various treatments. The pictures were labelled as follows to point out the changes: S (synovium), BoTa (tarsal bone), BoTi (tibial bone) and Ca (cartilage).

Treatment with DF 2162 ameliorates established AIA in rats

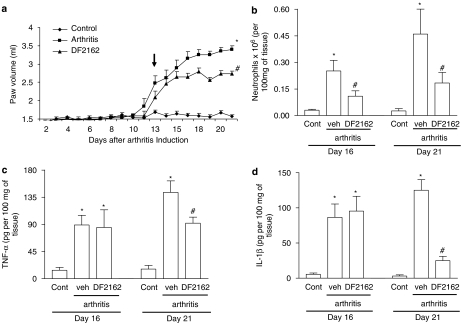

Next, we examined the effects of a more delayed treatment with DF 2162 on AIA in rats. Treatment was started on day 13, closer to the peak of the disease, and animals were evaluated daily for paw oedema and group were killed on days 16 and 21 for measurement of inflammatory parameters and cytokines. As seen in Figure 4a, delayed treatment with DF 2162 halted progression of the increase in paw volume, an inhibition that was significantly different from vehicle-treated animals from day 16 onwards. There was also partial inhibition of neutrophil influx, but not of the local concentration of IL-1β and TNF-α, at day 16 (Figures 4b–d). Neutrophil influx, TNF-α and IL-1β levels increased from days 16 to 21, reflecting the worsening of the disease, but treatment with DF 2162 significantly inhibited all of these parameters (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of the delayed treatment with DF 2162 in a model of adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. Treatment with DF 2162 (15 mg kg−1, twice daily) from day 13 after induction of disease (see arrow) inhibited the increase (a) in paw volume, (b) neutrophil influx, and local production of (c) TNF-α, IL-1β and (d) the chemokines CCL5 and CCL2. Results are mean±s.e.mean of five animals in each group. *P<0.01 when compared to non-arthritic animals (control (cont)); #P<0.01 compared to vehicle-treated arthritic (vehicle (veh)) rats. For experiments in (a), comparisons were made between areas under the curve.

Treatment with metabolite 1 but not metabolite 2 prevents AIA

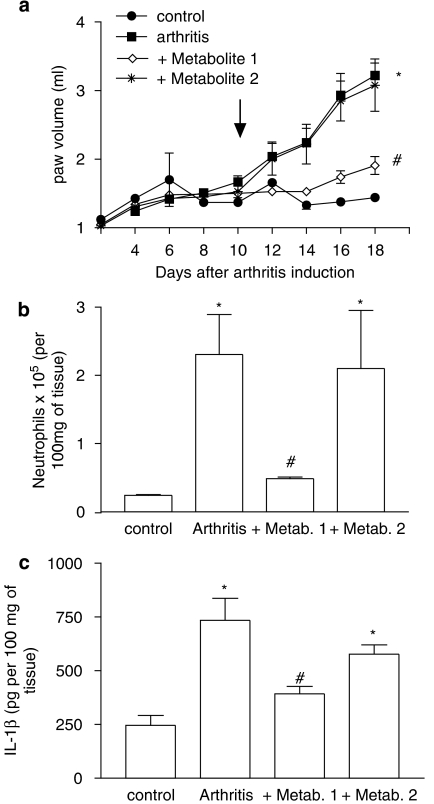

DF 2162 is metabolized into two major metabolites, 1 and 2. Whereas metabolite 1 retains the ability to block rat CXCR2, metabolite 2 is ineffective at this receptor (Figure 1b; Table 1). Figure 5 shows that only metabolite 1 effectively inhibited the increase of inflammatory parameters, including the increase of paw volume, neutrophil influx and the local production of IL-1β. Treatment with metabolite 2 resulted in inflammation virtually identical to vehicle-treated animals as assessed biochemically (Figure 5) and by histopathology (Figure 3g). Histopathological scores in arthritic animals treated with vehicle, metabolites 1 and 2 were 3 (0), 0.8 (1) and 2.8(1), respectively (P<0.05 when comparing vehicle and metabolite 1, data shown as median (interquartile range)).

Figure 5.

Effects of the treatment with the two major metabolites of DF 2162 in a model of adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. The effects of the treatment with metabolite 1 (3 mg kg−1, twice daily) and metabolite 2 (12 mg kg−1, twice daily) from day 10 after induction of disease (see arrow) on the increase (a) in paw volume, (b) neutrophil influx, and local production of (c) IL-1β are shown in the relevant panels. Results are mean±s.e.mean of five animals in each arthritic group and four non-arthritic animals. *P<0.01 compared to non-arthritic animals (control); #P<0.01 compared to vehicle-treated arthritic (vehicle) rats. For experiments in (a), comparisons were made between areas under the curve.

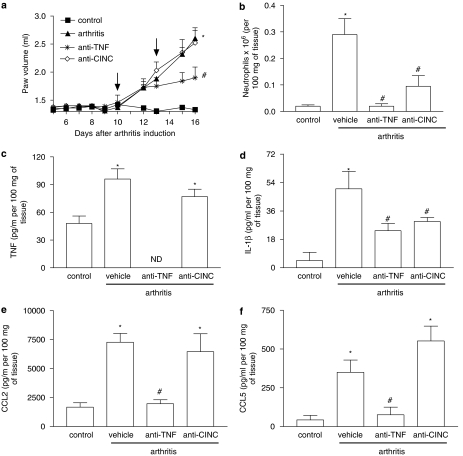

Effects of the treatment with anti-TNF-α and anti-CINC-1 antibodies on AIA

Treatment with anti-TNF-α antibody has become an important addendum to the available options for the care of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. As such, a series of experiments was conducted to evaluate the effects of anti-TNF-α antibody in our model of AIA in comparison to those of DF 2162. The effects of an anti-CINC-1 antibody were also evaluated in parallel. The antibodies were given at days 10 and 13 after arthritis induction. As seen in Figure 6, treatment with anti-TNF-α antibody partially inhibited the local increase in paw volume and greatly suppressed the infiltration of neutrophils and local production of cytokines, including IL-1β, CCL2 and CCL5. The anti-CINC-1 antibody was much less effective than the anti-TNF-α antibody and only partially inhibited the influx of neutrophils and the local production of IL-1β (Figure 6). Histological analysis concurred with the measurements above and showed a marked improved of joint inflammation in animals treated with anti-TNF-α (Figure 3e). There was less leukocyte infiltration in animals treated with anti-CINC-1 antibody, but cartilage and bone erosions were still present (Figure 3f). Histopathological scores in arthritic animals treated with control antibody, anti-TNF-α or anti-CINC-1 antibodies were 3 (0), 1 (0) and 1.8 (1), respectively (P<0.01 when comparing control and anti-TNF-α antibodies; data shown as median with (interquartile range)).

Figure 6.

Comparative effects of treatment with anti-TNF-α or anti-CINC-1 antibodies in a model of adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. The effects of the treatment with anti-TNF-α or anti-CINC-1 (5 μl g−1) on days 10 and 13 after induction of disease (see arrow) inhibited the increase (a) in paw volume, (b) neutrophil influx, and local production of (c) TNF-α, (d) IL-1β and the chemokines (e) CCL5 and (f) CCL2. Results are mean±s.e.mean of five animals in each group. *P<0.01 compared to non-arthritic animals (control (cont)); #P<0.01 compared to rats treated with non-immune serum (vehicle (veh)). For experiments in (a), comparisons were made between areas under the curve.

Discussion

The present study was conducted to investigate the potential effects of a therapeutic regimen using DF 2162 in a model of AIA in rats. DF 2162 was developed from reparixin, a non-competitive allosteric inhibitor of CXCL8 receptors (Bertini et al., 2004; Souza et al., 2004; Bizzarri et al., 2006). Our studies showed that DF 2162 was capable of inhibiting both hCXCR1 and hCXCR2 with only a 10-fold difference in potency. There is some controversy whether rats have both CXCR1 and CXCR2 (Dunstan et al., 1996; Murphy et al., 2000). Our results showed that DF 2162 blocked the action of CXCL1 on rat neutrophils, an action likely to be related to the rat CXCR2. DF 2162 was rapidly absorbed and possessed a half-life consistent with a twice-daily administration. Thus, DF 2162 was shown to be a novel, orally active inhibitor of both CXCR1 and CXCR2.

To mimic a potentially relevant clinical situation and to avoid any effect on the sensitization phase of arthritis induction, treatment with the compound was started on day 10 or 13 after disease induction. Our data clearly show that treatment with DF 2162 ameliorated the course of AIA when started at day 10 after disease induction. In DF 2162-treated animals, there was less oedema formation, less neutrophil influx, less local production of cytokines and amelioration of bone and cartilage erosion on histological sections of the joints. DF 2162 also prevented progression of AIA when started at day 13 after disease induction, although the effects of this treatment, more delayed, were not as marked as when the compound was started at day 10. Thus, treatment with an orally active, inhibitor of CXCR1/2 greatly ameliorated AIA in rats. In rabbits, treatment with N-(3-(aminosulphonyl)-4-chloro-2-hydroxyphenyl)-N′-(2,3-dichlorophenyl) urea, a CXCR2-selective receptor antagonist, inhibited neutrophil influx into the joint after administration of CXCL8 and lipopolysaccharide (Podolin et al., 2002). In contrast to the present study, the latter investigation dosed the compound daily from the day of challenge and did not investigate protection from joint damage. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation to demonstrate a clear-cut effect of an orally active CXCR1/2 antagonist given as a curative, not preventive, therapy for experimental arthritis.

DF 2162 is metabolized into two major metabolites in vivo (unpublished data on file in Dompé pha.r.ma). Although these molecules are structurally similar to DF 2162, only one retains the CXCR2-blocking activity of the molecule. The availability of these two structurally similar compounds gave us a unique opportunity to investigate the relevance of CXCR2 for the inhibitory effects of DF 2162 in our system. Our results showed that the metabolite active at CXCR2, but not the compound lacking action at CXCR2, ameliorated AIA in the rats. These data concur with the idea that blockade of CXCR2 is the relevant antiarthritic action of DF 2162.

CXCR1 and CXCR2 have been detected on neutrophils, macrophages/monocytes, cytokine-activated eosinophils, basophils, T lymphocytes, mast cells and dendritic cells (Pease and Williams, 2006). The role of both CXCR1 and CXCR2 for neutrophil migration in vivo has been demonstrated in several systems (Souza et al., 2004; Bizzarri et al., 2006; Rios-Santos et al., 2006). Much less is known of the relative functional in vivo importance for CXCR1/2 expression in many of the other cell types mentioned above. In our experiments, neutrophil influx was clearly diminished by treatment with DF 2162, suggesting that blockade of this cell type could underlie the beneficial antiarthritic effects observed. However, it is important to note that treatment with DF 2162 also diminished the production of the cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α, and of chemokines, CCL2 and CCL5, which have been shown to play a relevant role in driving tissue inflammation in models of experimental arthritis and in patients (Olsen and Stein, 2004; Shahrara et al., 2005; Haringman et al., 2006). Thus, blockade of CXCR1/2 by DF 2162 would be followed not only by inhibition of neutrophil influx but also by inhibition of the recruitment of different cell types and of the production of several relevant mediators of the inflammatory process. The blockade of the recruitment of these important cells and production of mediators, including TNF-α, could explain the overall prevention of cartilage and bone destruction. This is not to say that neutrophils themselves produce (or are the only producers of) the mediators responsible for the attraction of other cell types, including macrophages, or that they are necessarily the primary inducers of joint injury. In this regard, we have recently shown that prevention of PMN recruitment was associated with a strong reduction of tissue oedema, the main feature of contact hypersensitivity, suggesting that CXCR2 may indirectly regulate, through modulation of PMN infiltration, the recruitment of macrophages and hapten-primed effector T cells into sites of challenge (Cattani et al., 2006). Inhibition of neutrophil influx was also accompanied by inhibition of the infiltration of mononuclear cells into the rabbit joint (Podolin et al., 2002). Thus, our results are consistent with a role for CXCR2-induced neutrophil influx in the cascade of events leading to joint inflammation and injury.

The availability of strategies that prevent TNF-α action, such as antibodies or the soluble TNF-α receptor, has been an important addition to the therapeutic options for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Olsen and Stein, 2004). As such, any new therapeutic option will have to demonstrate at least similar (or complementary) therapeutic efficacy to anti-TNF-α antibody treatment. In our experiments, the administration of a polyclonal anti-rat TNF-α induced significant amelioration of neutrophil influx, cytokine and chemokine production, and of bone and cartilage erosion. Overall, the effects of anti-TNF-α were quantitatively and qualitatively similar to those of DF 2162 treatment. The latter results reinforce the concept that, akin to anti-TNF-α treatment, CXCR1/2 blockade may be a useful therapeutic strategy in the setting of arthritis.

The potential relevance of CXCL8 and CXCL8-like chemokines in the setting of arthritis was been suggested a long time ago (Brennan et al., 1990; revised by Wells et al., 2006). However, interest in the field was damped when treatment with an anti-CXCL8 antibody failed to induce improvement of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The reasons for the failure of these antibodies in the clinical setting are subject of much debate and beyond the scope of this discussion (see Bizzarri et al., 2006; Wells et al., 2006 for a review of the subject). In our studies, treatment with antibody against CINC-1, the rat homologue of CXCL1, one of the CXCR2-acting chemokines, was only accompanied by partial inhibition of joint inflammation and little effect on local cytokine/chemokine production. The antibody used here was, however, fully capable of blocking CXCL1 action in other models of inflammation (Souza et al., 2004). Our results are consistent with human trials suggesting that neutralization of a single CXCR1/2 agonist is not sufficient for effective treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. However, all of the many chemokines activating CXCR1/2 would be susceptible to antagonism by DF 2162, as the compound acts on the receptor and not on the chemokine.

In conclusion, this study describes that treatment with DF 2162, a novel orally active non-competitive allosteric inhibitor of CXCR1 and CXCR2, given as a curative, not preventive, therapy ameliorates AIA in rats. The effects of the compound appear to be associated with its ability to block the rat CXCR2 and are quantitatively and qualitatively similar to those of anti-TNF-α treatment. These findings highlight the contribution of CXCR2 in the pathophysiology of AIA and suggest that blockade of CXCR1/2 may be a valid therapeutic target for further studies aiming at the development of new drugs for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Acknowledgments

This work received financial support from Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisas do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG, Brazil), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico (CNPq, Brazil) and the European Union FP6 (INNOCHEM, Grant no. LSHB-CT-2005-518167).

Abbreviations

- AIA

adjuvant-induced arthritis

- Cmax

maximum concentration

- CINC-1

cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-1

- DF 2162

{4-[(1R)-2-amino-1-methyl-2-oxoethyl]phenyl trifluoromethanesulphonate}

- hCXCR

human CXC receptor

- NSAID

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PMN

polymorphonuclear

- TNF-α

tumour-necrosis factor-α

Conflict of interest

Marcello Allegretti, Franca Cattani, Federica Policani, Cinzia Bizzarri and Riccardo Bertini are employees of Dompé pha.r.ma s.p.a., Italy.

References

- Barcelos LS, Talvani A, Teixeira AS, Vieira LQ, Cassali GD, Andrade SP, et al. Impaired inflammatory angiogenesis, but not leukocyte influx, in mice lacking TNFR1. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:352–358. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1104682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsante MM, Roffe E, Yokoro CM, Tafuri WL, Souza DG, Pinho V, et al. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of atorvastatin in a rat model of adjuvant-induced arthritis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;516:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini R, Allegretti M, Bizzarri C, Moriconi A, Locati M, Zampella G, et al. Noncompetitive allosteric inhibitors of the inflammatory chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2: prevention of reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11791–11796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402090101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzarri C, Beccari AR, Bertini R, Cavicchia MR, Giorgini S, Allegretti M. ELR+ CXC chemokines and their receptors (CXC chemokine receptor 1 and CXC chemokine receptor 2) as new therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan FM, Zachariae CO, Chantry D, Larsen CG, Turner M, Maini RN, et al. Detection of interleukin 8 biological activity in synovial fluids from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and production of interleukin 8 mRNA by isolated synovial cells. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:2141–2144. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattani F, Gallese A, Mosca M, Buanne P, Biordi L, Francavilla S, et al. The role of CXCR2 activity in the contact hypersensitivity response in mice. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:42–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl KH, Hull R, Morton D, Pfister R, Rabemampianina Y, Smith D, European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries Association and European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods et al. A good practice guide to the administration of substances and removal of blood, including routes and volumes. J Appl Toxicol. 2001;21:15–23. doi: 10.1002/jat.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunstan CA, Salafranca MN, Adhikari S, Xia Y, Feng L, Harrison JK. Identification of two rat genes orthologous to the human interleukin-8 receptors. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32770–32776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk W, Goodwin RH, Jr, Leonard EJ. A 48-well micro chemotaxis assembly for rapid and accurate measurement of leukocyte migration. J Immunol Methods. 1980;33:239–247. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(80)90211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestein GS. Inhibiting inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:80–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr054344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischi JN, Yokoro CM, Poole S, Tafuri WL, Cunha FQ, Teixeira MM. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of the phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor rolipram in a rat model of arthritis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;399:243–249. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garau A, Bertini R, Mosca M, Bizzarri C, Anacardio R, Triulzi S, et al. Development of a systemically-active dual CXCR1/CXCR2 allosteric inhibitor and its efficacy in a model of transient cerebral ischemia in the rat. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006. pp. 35–41. [PubMed]

- Garrood T, Pitzalis C. Targeting the inflamed synovium: the quest for specificity. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1055–1060. doi: 10.1002/art.21720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard C, Rollins BJ. Chemokines and disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:108–115. doi: 10.1038/84209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas CS, Martinez RJ, Attia N, Haines GK, III, Campbell PL, Koch AE. Chemokine receptor expression in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3718–3730. doi: 10.1002/art.21476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haringman JJ, Gerlag DM, Smeets TJ, Baeten D, van den Bosch F, Bresnihan B, et al. A randomized controlled trial with an anti-CCL2 (anti-monocyte chemotactic protein 1) monoclonal antibody in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2387–2392. doi: 10.1002/art.21975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasama T, Miwa Y, Isozaki T, Odai T, Adachi M, Kunkel SL. Neutrophil-derived cytokines: potential therapeutic targets in inflammation. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2005;4:273–279. doi: 10.2174/1568010054022114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti BB, Veiga FH, Canetti CA, Poole S, Cunha FQ, Ferreira SH. Cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant 1 (CINC-1) mediates the sympathetic component of inflammatory mechanical hypersensitivity in rats. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2002;13:456–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos IM, Souza DG, Seabra DG, Freire-Maia L, Teixeira MM. Effects of tachykinin NK1 or PAF receptor blockade on the lung injury induced by scorpion venom in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;376:293–300. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa A, Yoshimura T, Fujiwara K, Maeda T, Ohkawara S, Yoshinaga M. Involvement of growth-related protein in lipopolysaccharide-induced rabbit arthritis: cooperation between growth-related protein and IL-8, and interrelated regulation among TNFalpha, IL-1, IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-8, and growth-related protein. Lab Invest. 1999;79:591–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PM, Baggiolini M, Charo IF, Hebert CA, Horuk R, Matsushima K, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXII. Nomenclature for chemokine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:145–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura A, Akahoshi T, Takahashi M, Takagishi K, Itoman M, Kondo H, et al. Attenuation of monosodium urate crystal-induced arthritis in rabbits by a neutralizing antibody against interleukin-8. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:444–449. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen NJ, Stein CM. New drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2167–2179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer G, Gabay C, Imhof BA. Leukocyte migration to rheumatoid joints: enzymes take over. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2707–2710. doi: 10.1002/art.22062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease JE, Williams TW. The attraction of chemokines as a target for specific anti-inflammatory therapy. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:S212–S221. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolin PL, Bolognese BJ, Foley JJ, Schmidt DB, Buckley PT, Widdowson KL, et al. A potent and selective nonpeptide antagonist of CXCR2 inhibits acute and chronic models of arthritis in the rabbit. J Immunol. 2002;169:6435–6444. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios-Santos F, Alves-Filho JC, Oliveira Souto F, Spiller F, Freitas A, Monteiro CLC, et al. Down-regulation of CXCR2 on neutrophils in severe sepsis is mediated by iNOS-derived nitric oxide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;175:490–497. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200601-103OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahrara S, Amin MA, Woods JM, Haines GK, Koch AE. Chemokine receptor expression and in vivo signaling pathways in the joints of rats with adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3568–3583. doi: 10.1002/art.11344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahrara S, Proudfoot AE, Woods JM, Ruth JH, Amin MA, Park CC, et al. Amelioration of rat adjuvant-induced arthritis by Met-RANTES. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1907–1919. doi: 10.1002/art.21033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza DG, Bertini R, Vieira AT, Cunha FQ, Poole S, Allegretti M, et al. Repertaxin, a novel inhibitor of rat CXCR2 function, inhibits inflammatory responses that follow intestinal ischaemia and reperfusion injury. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:132–142. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza DG, Cassali GD, Poole S, Teixeira MM. Effects of inhibition of PDE4 and TNF-alpha on local and remote injuries following ischaemia and reperfusion injury. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:985–994. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells TN, Power CA, Shaw JP, Proudfoot AE. Chemokine blockers—therapeutics in the making. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]