Abstract

Background and purpose:

Spinal N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor/cyclooxygenase (COX) and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) pathways play a major role in nociceptive processing, and influencing them simultaneously may induce synergistic analgesia. This study determined the spinal antinociceptive interactions between ketamine (NMDA receptor channel blocker), ketoprofen (COX inhibitor) and L-NAME (NOS inhibitor) combinations.

Experimental approach:

Using an in vitro neonatal rat spinal cord preparation, two A-fibre-mediated reflexes, the monosynaptic reflex (MSR) and the low-intensity excitatory postsynaptic potential (epsp), and one C-fibre-mediated reflex, the high-intensity epsp, were evoked electrically. The effect of drugs and drug combinations on these reflexes was assessed and the type of interaction determined by isobolographic analysis.

Key results:

Infusion of ketamine alone decreased all three reflexes. That of ketoprofen decreased both the low and the high-intensity epsp only. Infusion of L-NAME alone produced no significant effects. Co-infusion of fixed ratios of IC40 fractions of both (ketamine+ketoprofen) and (ketamine+L-NAME) were synergistic for depressing the low and the high-intensity epsps. The interaction was sub-additive for both combinations on the MSR. The only significant effect for the (ketoprofen+L-NAME) combination was synergism on the high-intensity epsp.

Conclusions and implications:

All three combinations synergistically depressed nociceptive spinal transmission, and both ketamine and ketoprofen and ketamine and L-NAME combinations did so with potentially decreased motor side effects. If such combination profiles also occur in vivo, the present findings raise the possibility of ultimate therapeutic exploitation of increased analgesia with fewer side effects.

Keywords: synergism, isobolographic analysis, ketamine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, L-NAME, spinal cord, nociceptive transmission, NMDA receptors, nitric oxide synthase

Introduction

Although many methods and drugs are available for pain therapy, the search for more effective ways of relieving pain continues. As a large number of receptor systems and pathways are involved in the nociceptive processing of information (Dickenson, 1995), intuitively it would be more effective to influence them simultaneously. Spinal administration of drug combinations that act at different nociceptive receptor systems may be an adequate way to overcome some of the limitations of conventional therapies. Analgesic combinations should, however, satisfy two important pharmacodynamic criteria: the drugs in the combination should display additive or synergistic antinociception and fewer side effects (Yaksh and Malmberg, 1994).

Currently, subdural administration of opioid agonists is a common procedure to control some types of pain, but the side effects and limitations of spinally administered opioid analgesics (for example, delayed respiratory depression, pruritus) (Channey, 1995) confirm the need for alternatives. It is widely accepted that spinal NMDA receptors play a key role in nociception (Bennett, 2000). Intrathecal (i.t.) administration of NMDA receptor antagonists reduces spinal hyper-excitability (Harris et al., 2004) and induces antinociception in a number of animal pain models (Dolan and Nolan, 1999; Park et al., 2000; Yaksh et al., 2001; Liaw et al., 2005). Analgesia has also been reported following i.t. administration of the NMDA receptor channel blocker ketamine in human beings (Benrath et al., 2005). Although relatively safe, i.t. administration of ketamine can produce unwanted side effects such as motor block and acute psychotic alterations (Hawksworth and Serpell, 1998; Lauretti et al., 2001). These side effects may arise from the fact that NMDA receptors are widespread in the CNS and are involved in many physiological processes (Dingledine et al., 1999). This may limit the use of i.t. ketamine as monotheraphy for the treatment of pain.

Activation of spinal NMDA receptors can trigger the arachidonic acid (AA)/COX/prostaglandin (PG) signalling pathways and induce allodynia and hyperalgesia (Malmberg and Yaksh, 1992; Yaksh et al., 2001). The i.t. administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, which inhibit COX enzymes) reduce the hyper-excitability of spinal dorsal horn neurones (Willingale et al., 1997) and inhibit the hyperalgesic response after i.t. NMDA administration (Dolan and Nolan, 1999; Park et al., 2000; Yaksh et al., 2001). Case reports also suggest that i.t. injection of NSAIDs produce antihyperalgesia in humans (Devoghel, 1983). The i.t. route of administration for these drugs has recently entered clinical trials (Eisenach et al., 2002).

Activation of NMDA receptors can also stimulate the nitric oxide (NO) signalling pathway, which has been shown to play an important role in spinal nociceptive processing. For example, in adult rats, i.t. administration of NMDA induces pain-related behaviours at the same time as it increases the concentration of the stable products of NO, nitrite and nitrate, in CSF (Kawamata and Omote, 1999). The i.t. administration of drugs that antagonize NMDA receptors or inhibit NOS and soluble guanylate cyclases block NMDA-induced nociception (Kawamata and Omote, 1999; Fairbanks et al., 2000). In addition, in vitro experiments have shown that NMDA treatment increases the release of cGMP from the spinal cord of adult rats, and this increase can be blocked by NOS inhibitors (Kawamata and Omote, 1999). Thus, activation of spinal NMDA receptors may induce pain at least by stimulating NOS to produce NO, which in turn may activate soluble guanylate cyclases to increase cGMP formation. Accordingly, analgesia, probably partially mediated at the level of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, has also been demonstrated after systemic administration of a NOS inhibitor in patients with chronic tension-type headache (Ashina et al., 1999).

As NMDA receptor antagonists, NSAIDs and NOS inhibitors are likely to have overlapping influences in the intracellular events that subserve spinal nociceptive transmission, spinal antinociceptive interactions between these classes of compounds remain strong possibilities. In fact, the analgesic effects of several NSAIDs were increased by a non-analgesic dose of the NMDA receptor antagonist dextromethorphan in a rat model of arthritic pain (Price et al., 1996). However, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trials showed that pain relief associated with dextromethorphan and NSAID treatment was not superior to that obtained with an equal dose of dextromethorphan or the NSAID alone in patients scheduled for surgical termination of pregnancy (Ilkjær et al., 2000) or elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Yeh et al., 2004). These studies did not use a fixed-ratio combination design and no isobolar analysis could be carried out. This precluded the characterization of the drug interaction rendering the findings suggestive, but inconclusive.

Similarly, two separate investigations, one in mice (Bulutcu et al., 2002) and the other in humans (Lauretti et al., 2001), suggested that ketamine may activate the NO pathway to exert its central analgesic effects. Nonetheless, no isobolograms were constructed to determine the nature of the interaction between the compounds used in these studies.

Other studies have evaluated a possible interaction between the NO pathway and analgesia induced by NSAIDs both at the peripheral and spinal cord levels (Morgan et al., 1992; Björkman et al., 1996; Lorenzetti and Ferreira, 1996; Sandrini et al., 2002; Díaz-Reval et al., 2004; Dudhgaonkar et al., 2004; Lozano-Cuenca et al., 2005). However, no isobolographic studies investigating the spinal antinociceptive effect of the interaction between NSAIDs and NOS inhibitors have been reported.

The current study examined the interactions between ketamine, ketoprofen and Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) on electrophysiological segmental transmission in an in vitro neonatal rat spinal cord preparation. Fixed-ratio combination designs were used to distinguish between additive and non-additive drug interactions. It was hypothesized that the drug combinations would act synergistically to depress spinal nociceptive transmission. Preliminary data have been published in abstract form (Lizarraga et al., 2005).

Materials and methods

Spinal cord preparation

All animal procedures were approved by the Massey University Animal Ethics Committee (protocol number 02/103). Experiments were carried out as described previously (Lizarraga et al., 2006). Briefly, unsexed, 5- to 7-day-old Sprague–Dawley rats were killed by cervical dislocation and decapitation and the spinal cords, with attached dorsal and ventral roots, removed. The spinal cords were hemisected sagittally and placed in a chamber with L4 or L5 dorsal root in contact with the stimulating Ag/AgCl2 wire electrodes and the corresponding ventral root in contact with the recording Ag/AgCl2 wire electrodes. The hemicords were perfused (2 ml min−1) with artificial CSF of the following composition (mM): NaCl, 118; NaHCO3, 24; glucose, 12; CaCl2, 1.5; KCl, 3; and MgSO4·7H2O, 1.25. The artificial CSF was gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and was kept at room temperature (21–25 °C). Preparations were allowed to equilibrate for 60 min before recordings started.

Recording techniques

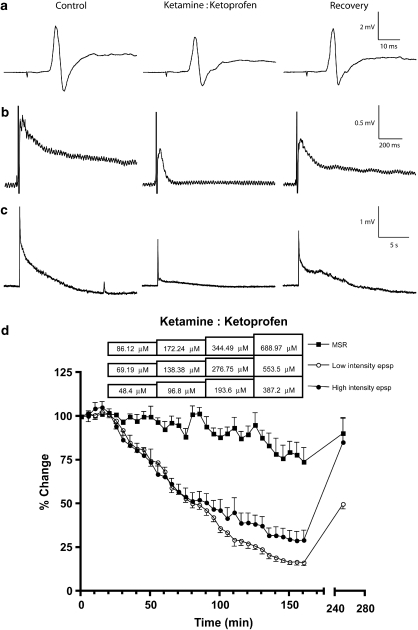

Electrical stimulation of the dorsal root with single, 0.5 ms, square wave pulses at three times threshold (threshold being the intensity at which a discernible response first appeared in the ventral root) produced two A-fibre-mediated synaptic responses: the monosynaptic reflex (MSR; Figure 1a) superimposed on a population excitatory postsynaptic potential (epsp) and the low-intensity epsp (Figure 1b), which lasts up to 2 s (Faber et al., 1997). Both responses have glutamate receptor-mediated components, with the former being mediated by kainate and AMPA receptors and the latter by NMDA receptors (Long et al., 1990; Woodley and Kendig, 1991; Faber et al., 1997). Stimulation at 32 times threshold evoked an additional C-fibre-mediated response, the high-intensity epsp (Figure 1c), which lasts up to tens of seconds (Akagi et al., 1985; Faber et al., 1997). This response possesses both NMDA receptor and neuropeptide components (Akagi et al., 1985; Woodley and Kendig, 1991). In sciatic nerve–dorsal root preparations from age-matched rats, voltage stimulation at three times threshold activated A-fibre afferents only, and at 32 times threshold, C-fibre afferents were also activated (Lizarraga et al., 2007). Responses were amplified (AA6 Mk III, Medelec MS6 system; Medelec Ltd, Woking, Surrey, UK), transferred to a PowerLab 4/20 (ADInstruments Pty Ltd, Castle Hill, New South Wales, Australia) and digitally stored for off-line analysis (Scope v3.6.8, MacLab System 1998; ADInstruments Pty Ltd).

Figure 1.

Effects of ketamine+ketoprofen combinations on the synaptic responses. The combinations depressed the low-intensity epsp (b) and the high-intensity epsp (c), but had a minor effect on the MSR (a). Recordings in the left panels show the control responses (time 0 min), each one from a different preparation, those in the middle panels represent the depressive effects of the ketamine+ketoprofen combinations (time 160 min) and those in the right panels illustrate their recovery after 90 min of drug-free medium (time 250 min). (d) Time course showing the actions of ketamine+ketoprofen combinations, each concentration infused for 35 min, on the different components of the synaptic response. Fractions were 0.045:0.955 for the MSR and the low-intensity epsps, and 0.048:0.952 for the high-intensity epsp. Each point represents the mean±s.e.mean of four preparations for each one of the synaptic responses. epsp, excitatory postsynaptic potential; MSR, monosynaptic reflex.

Effect of treatment

Segmental reflexes were recorded every 5 min. After obtaining at least three baseline readings, cumulative concentrations of ketamine (1–50 μM), ketoprofen (200–600 μM) and L-NAME (1–100 μM) were applied to the hemicords by adding them to the superfusate (drug concentrations correspond to final concentrations in the superfusate). Each ketamine concentration was infused for 30 min and those of ketoprofen for 35 min, which were the times required for each drug to reach equilibrium; this being defined as three consecutive recordings being not significantly different from each other after starting the administration of the tested drug (Lizarraga et al., 2006). L-NAME concentrations, which produced no apparent effect, were infused for 45 min each. The drug concentration ranges were selected from previous studies using a neonatal rat spinal cord preparation (Brockmeyer and Kendig, 1995; Thompson et al., 1995; Lizarraga et al., 2006). A final recording was taken 90 min after washout when the drug depressed the synaptic response or 30 min after washout when the drug had no apparent effect. Infusions lasted 30 min for each concentration when ketamine was included in the drug combination and 35 min when ketoprofen was part of the combination; when these two drugs were tested together, infusions lasted 35 min for each concentration (Figure 1d). Only one reflex and treatment were studied per preparation.

The effect of treatment was assessed by converting the peak amplitude of the MSR and the area under the curve of both the low-intensity epsp and the high-intensity epsp into MPE% (percentage maximal possible effect) values according to the formula: %MPE=100−[(post-drug effect/baseline effect) × 100]. MPE% values from the last recording for each treatment concentration (at least four concentrations per treatment) and preparation (4–5 different preparations per reflex) were used to perform linear regression analysis of log concentration–effect data (GraphPad Prism, v4.0b for Macintosh; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). After assessing the regression lines for parallelism (F-test, GraphPad Prism), the inhibitory concentration necessary to achieve 40% MPE (IC40) together with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was computed for each drug alone.

Composite additive line and isobolographic analyses

Drug interactions were evaluated by co-administering fixed proportions of ketamine+ketoprofen, ketamine+L-NAME and ketoprofen+L-NAME. The analysis of the different combinations was performed as described by Tallarida et al. (1997) and Porreca et al. (1990). The former methodology was used when both drugs in the combination showed efficacy when administered alone and it used individual concentration–effect data to construct composite additive lines using values over the range of effects common to the two compounds. The sum of both constituents in an additive combination (Zadd) for individual concentration–effect data (z) was computed according to the following equations: Zadd=z1/(p1+Rp2) and Zadd=z2/(p1/R+p2) (Tallarida et al., 1997). The less-potent drug was depicted as 1, whereas the more potent drug as 2, and R represented the relative potency of each concentration–effect point with respect to the other drug at that effect level (drug 1:drug 2). The fixed-ratio combinations were arbitrarily determined by taking 0.5 fractions of the IC40 of each compound, which were used to calculate proportions of drug 1 (p1) and drug 2 (p2). The translated points of both drugs resulted in a set of data that were the composite of both and were fitted to a regression line of additivity for the drug pair. Isobolograms were constructed by connecting the IC40 of one drug plotted on the ordinate with the IC40 of the other plotted on the abscissa and considering theoretical additive IC40 values and their 95% CI derived from linear regression analysis of the composite additive curve. In this case, the additive isobole is not a straight line.

For each one of the actual drug combinations tested experimentally, in which the constituents were infused in amounts that kept the proportions of each constant, the IC40 and its 95% CI were determined by linear regression analysis of the log concentration–response data and compared to its respective theoretical additive IC40 value.

For interactions involving one drug that lacked efficacy, the method described by Porreca et al. (1990) was conducted. In this case, isobolograms were constructed with the IC40 of the active drug plotted on the ordinate, which produced horizontal lines of additivity. As mentioned before, IC40 values together with 95% CI were computed for each drug combination and were compared to corresponding theoretical additive values obtained from the calculation: IC40add=A/fA, where A was the IC40 of the efficacious drug and fA the fraction of A in the combination (Porreca et al., 1990). Because A had 95% CI, CI(IC40add) was calculated as CI(A)/fA.

Synergism was defined as the effect of a drug combination being higher and statistically different (IC40 significantly less) than the theoretically calculated equi-effect of a drug combination with the same proportions. In contrast, the effect of a drug combination being lower and statistically different (IC40 significantly more) than the theoretically calculated equi-effect of a drug combination with the same proportions was regarded as sub-additivity. When the drug combination gave an experimental IC40 not statistically different from the theoretically calculated IC40, the combination was deemed to have an additive effect. Additivity meant that each constituent contributed to the effect in accord with its own potency, and the less potent drug was merely acting as a diluted form of the other (Tallarida, 2000).

Statistics

Data were presented as IC40 values with 95% CI. IC40 values for the theoretical additive combination and the actual drug combination tested experimentally were compared using Student's t-test (Tallarida, 2000). Differences were taken to be significant when P<0.05.

Drugs

Ketamine was dissolved in distilled water and ketoprofen in distilled water and NaOH (no more than 672 μM, final concentration). Stock solutions of both drugs were kept at 4 °C. L-NAME was prepared freshly in artificial CSF each experimental day. All drugs were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

Results

Single drug studies

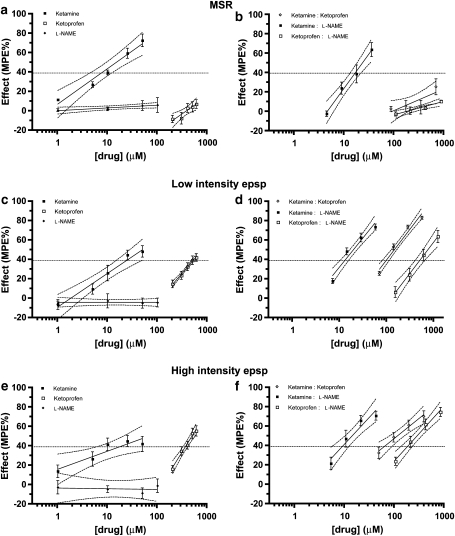

Cumulative increases in ketamine concentrations decreased all three types of reflexes; IC40 values (with 95% CI) were 7.75 μM (5.94–10.00 μM) for the MSR, 24.85 μM (16.78–42.80 μM) for the low-intensity epsp and 18.63 μM (8.62–79.87 μM) for the high-intensity epsp. Ketoprofen decreased both the low-intensity epsp (528.64 μM (452.85–683.19 μM)) and the high-intensity epsp (368.55 μM (326.72–414.85 μM)), with very minor efficacy on the MSR (maximum depression of 7.42±4.61%, slope significantly different from zero, P=0.0097, F-test). L-NAME had no effect on any of the spinal reflexes, and the concentration–response lines yielded slopes not significantly different from zero (P⩾0.3479, F-test) (Figures 2a, c and e).

Figure 2.

Percent maximal possible effect (MPE%) of ketamine, ketoprofen and L-NAME alone on the MSR (a), the low-intensity epsp (c) and the high-intensity epsp (e), MPE% for the actual combinations of ketamine:ketoprofen, ketamine:L-NAME and ketoprofen:L-NAME on the MSR (b), the low-intensity epsp (d) and the high-intensity epsp (f). Each point represents the mean±s.e.mean of four preparations for each one of the synaptic responses, except for ketamine and ketoprofen alone and ketoprofen+L-NAME combination on the low-intensity epsp, for which five preparations per treatment were used. epsp, excitatory postsynaptic potential; L-NAME, Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; MSR, monosynaptic reflex.

Ketamine and ketoprofen combination

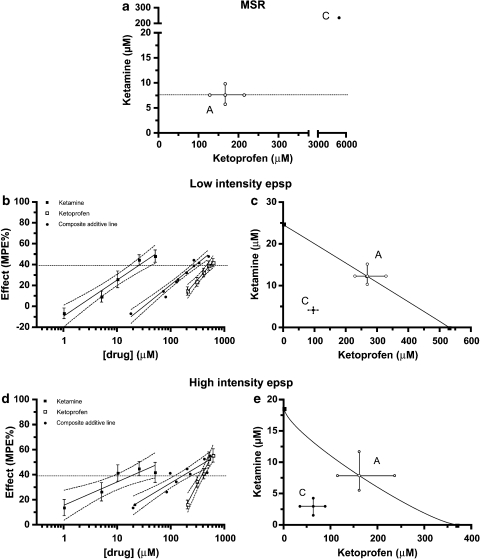

The concentration–response lines obtained with ketamine and ketoprofen alone were not parallel for both the low-intensity epsp and the high-intensity epsp (P>0.05, F-test), suggesting that the relative potency of both drugs was not constant (Figures 2c and e). Taking this into consideration, theoretical additive IC40 values with 95% CI were computed from linear regression analysis of composite additive lines, which used fixed ratios of 0.5 fractions of the IC40 of ketamine and ketoprofen alone (Figures 3b and d, Table 1).

Figure 3.

Isobolograms for the MSR (a), the low-intensity epsp (c) and the high-intensity epsp (d, e) at an effect level of 40% depression of the maximal possible effect for the combinations ketamine+ketoprofen in fixed-ratio proportions (0.045:0.955 for the MSR and the low-intensity epsp, and 0.048:0.952 for the high-intensity epsp). Points A represent the calculated additivity quantities for these proportional combinations. Points C are the combination points determined experimentally with these same proportional mixes. Confidence intervals for point C in (a) are too wide and hence not plotted. Percent maximal possible effect (MPE%) of ketoprofen alone, ketamine alone and their composite additive line in the above cited proportions are shown for the low-intensity epsp (b) and the high-intensity epsp (e). epsp, excitatory postsynaptic potential; MSR, monosynaptic reflex.

Table 1.

Theoretical additive and actual experimental IC40 values with 95% CIs (in μM) for combinations of ketamine+ketoprofen, ketamine+L-NAME and ketoprofen+L-NAME in fixed-drug proportions on the three evoked spinal segmental responses

| Segmental response |

Ketamine:ketoprofena |

Ketamine:L-NAMEb |

Ketoprofen:L-NAMEb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | Experimental | Theoretical | Experimental | Theoretical | Experimental | |

| MSR | 172.24 (131.97–222.18) | 5407.67 (1114.01–3.82 × 1020)‡ | 8.80 (6.74–11.36) | 16.43 (13.12–21.63)‡ | N/E | N/E |

| Low-intensity epsp | 278.21 (234.23–343.21) | 97.62 (81.12–113.63)‡ | 28.22 (19.06–48.60) | 13.06 (10.37–15.71)† | 600.37 (514.31–775.91) | 503.25 (403.59–646.54) |

| High-intensity epsp | 167.15 (118.82–246.75) | 64.72 (34.81–91.36)† | 21.16 (9.79–90.71) | 9.14 (5.71–12.39) | 418.57 (371.06–471.15) | 185.86 (135.64–235.38)† |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; epsp, excitatory postsynaptic potential; L-NAME, Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; MSR, monosynaptic reflex; N/E, no effect.

†P<0.05 and ‡P<0.01 between theoretical and experimental values.

Proportions were 0.045:0.955 for the MSR and the low-intensity epsp, and 0.048:0.952 for the high-intensity epsp.

Proportions were 0.8805:0.1195 for all three evoked segmental responses.

Co-infusion of fixed ratios of ketamine and ketoprofen (Table 2, Figures 1d, 2b, d and f) resulted in a synergistic depressive effect at the level of 40% reduction of the control response on both the low-intensity epsp (P<0.01; Figure 3c) and the high-intensity epsp (P<0.05; Figure 3e).

Table 2.

Actual drug concentrations (μM) infused onto the hemisected spinal cords for combinations of ketamine+ketoprofen, ketamine+L-NAME and ketoprofen+L-NAME in fixed drug proportions on the three evoked segmental responses

| Segmental response | Ketamine+ketoprofen (μM) | Ketamine+L-NAME (μM) | Ketoprofen+L-NAME (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSR | 3.87+82.25 | 3.87+0.53 | 92.14+12.50 |

| 7.75+164.49 | 7.75+1.05 | 184.27+25.01 | |

| 15.50+328.98 | 15.50+2.10 | 368.55+50.02 | |

| 31.00+657.97 | 31.00+4.20 | 737.10+100.04 | |

| Low-intensity epsp | 3.11+66.07 | 6.21+0.84 | 132.16+17.93 |

| 6.22+132.15 | 12.42+1.69 | 264.32+35.87 | |

| 12.45+264.30 | 24.85+3.37 | 528.64+71.74 | |

| 24.90+528.60 | 49.70+6.74 | 1057.28+143.49 | |

| High-intensity epsp | 2.32+46.08 | 4.66+0.63 | 92.14+12.50 |

| 4.65+92.15 | 9.32+1.26 | 184.27+25.01 | |

| 9.30+184.30 | 18.63+2.53 | 368.55+50.02 | |

| 18.60+368.60 | 37.26+5.06 | 737.10+100.04 |

Abbreviations: epsp, excitatory postsynaptic potential; L-NAME, Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; MSR, monosynaptic reflex.

For the MSR, on which ketoprofen had very minor efficacy when infused alone (Figure 2a), the same ketamine:ketoprofen proportion used for the low-intensity epsp (0.045:0.955) was chosen arbitrarily to calculate the additive IC40 value with its corresponding 95% CI (Table 1). Administration of ketamine and ketoprofen in amounts that kept the proportions of each constant was not sufficient to achieve a 40% reduction of the control response (mean±s.e.mean maximum reduction of 25.92±8.25%; Figure 2b). The estimated mean IC40 value and 95% CI of the actual mix were significantly higher than those of the corresponding additive mixture with these proportions, which suggests a sub-additive effect (Table 1). This is shown isobolographically in Figure 3a, in which the theoretical line of additivity is horizontal.

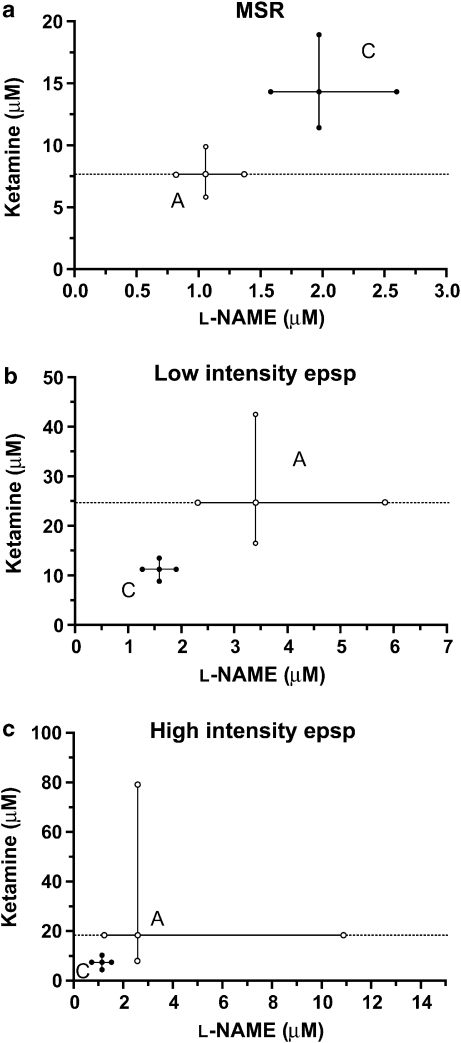

Ketamine and L-NAME combination

As L-NAME produced no significant effect when infused alone (Figures 2a, c and e), an arbitrary fixed drug proportion of ketamine and L-NAME (0.8805:1195) was used to calculate the theoretical additive IC40 values with their corresponding 95% CI for the three spinal reflexes. Theoretical additive and actual combination IC40 values for each one of the segmental responses are presented in Table 1, and drug concentrations actually tested for this combination on each of the spinal reflexes are given in Table 2. The IC40 for the actual combination was significantly higher than the theoretically calculated value for the MSR (P<0.01), which indicates a sub-additive interaction for the combination, and this is expressed isobolographically in Figure 4a.

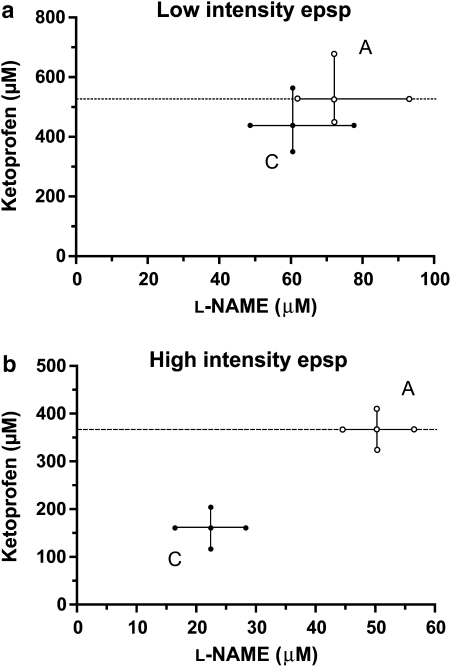

Figure 4.

Isobolograms for the MSR (a), the low-intensity epsp (b) and the high-intensity epsp (c) at an effect level of 40% depression of the maximal possible effect for the combination ketamine+L-NAME in a fixed-ratio proportion (0.8805:0.1195 for all three responses). Points A represent the calculated additivity quantities for these proportional combinations. Points C are the combination points determined experimentally with these same proportional mixes. epsp, excitatory postsynaptic potential; L-NAME, Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; MSR, monosynaptic reflex.

In contrast to the MSR, IC40 values for the low-intensity epsp were significantly higher for the theoretical additive combination than the actual combination (P<0.05), demonstrating a synergistic interaction between ketamine and L-NAME (Figure 4b).

For the high-intensity epsp, the combination of ketamine and L-NAME was additive at the IC40 level, as both theoretical additive and actual combination values were not significantly different (P>0.05; Figure 4c).

Ketoprofen and L-NAME combination

As for the ketamine and L-NAME combination, an arbitrary fixed drug proportion of ketoprofen and L-NAME (0.8805:1195) was used to calculate the additive IC40 values with their corresponding 95% CI for the three spinal reflexes (Table 1). Co-infusion of ketoprofen and L-NAME, in amounts that kept the proportions of each constant (Table 2), produced a synergistic depressive effect on the C-fibre-mediated high-intensity epsp at the level of 40% reduction of the control response (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Isobolograms for the low-intensity epsp (a) and the high-intensity epsp (b) at an effect level of 40% depression of the maximal possible effect for the combination ketoprofen+L-NAME in a fixed-ratio proportion (0.8805:0.1195 for both responses). Points A represent the calculated additivity quantities for these proportional combinations. Points C are the combination points determined experimentally with these same proportional mixes. epsp, excitatory postsynaptic potential; L-NAME, Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester.

A-fibre-evoked reflexes, on the contrary, showed an additive response to the co-infusion of ketoprofen and L-NAME (Table 1). The isobologram in Figure 5a illustrates this at an effect level of the 40% reduction of the control response for the low-intensity epsp. Similar to the administration of either drug alone, co-infusion of ketoprofen and L-NAME had only a minor effect on the MSR; mean±s.e.mean maximum depression of 11±1.20% of the control response (Figure 2b).

Discussion

The present study examined the nature of the interactions between the NMDA receptor channel blocker ketamine, the NSAID ketoprofen and the NOS inhibitor L-NAME on spinal nociceptive reflexes. The results demonstrated synergistic antinociceptive interactions, which may allow lower doses of drugs, with reduced potential side effects, to be used.

The fact that both ketamine and ketoprofen alone reduced the low-intensity and the high-intensity epsps, which have NMDA components (Brockmeyer and Kendig, 1995; Faber et al., 1997), may indicate that they have an effect on NMDA receptor-mediated transmission. This was expected for ketamine, as it is a non-competitive NMDA receptor channel blocker and, similar to other NMDA receptor antagonists (Faber et al., 1997), has been shown to reduce both the low-intensity and the high-intensity epsps (Brockmeyer and Kendig, 1995; Lizarraga et al., 2006). The depressive effects of ketoprofen alone were also expected, as NSAIDs are capable of preventing NMDA-induced nociception (Malmberg and Yaksh, 1992; Dolan and Nolan, 1999; Park et al., 2000; Yaksh et al., 2001) and this NSAID has been shown to depress nociceptive transmission on the in vitro neonatal rat spinal cord preparation (Lizarraga et al., 2006).

Ketamine and ketoprofen combination

Few studies have addressed the analgesic interaction between NMDA receptor antagonists and NSAIDs. To date, the most detailed study was that in which the analgesic effects of several NSAIDs were increased by a non-analgesic dose of the putative NMDA receptor antagonist dextromethorphan in a rat model of arthritic pain (Price et al., 1996). The authors concluded that the interaction was synergistic despite not using isobolographic analysis, justifying that such analysis was not carried out due to the lack of analgesic efficacy of dextromethorphan alone. However, isobolographic analysis in which one of the two drugs of interest lacks efficacy alone can be performed (Porreca et al., 1990; this report). This highlights the lack of isobolographic analysis in the literature and does not rule out the possibility of additive, but not detectable, effects between these compounds. Another drawback of the dextromethorphan study was the uncertainty of the location of the suggested synergistic effect (that is peripheral, central or both), as drugs were administered systemically (that is orally and intraperitoneally). Dextromethorphan undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism (Wills and Martin, 1988), and the parent drug binds with high affinity to σ1 receptors in comparison to the phencyclidine binding site in the NMDA receptor (Ki=419 vs 3500 nM, respectively), whereas its metabolite dextrorphan binds with similar affinity to both (Ki=559 vs 460 nM, respectively) (Newman et al., 1996). Hence, the effects of dextromethorphan, or even dextrorphan, cannot be solely attributed to the blockade of the NMDA receptor ion pore.

The interactions between ketamine and ketoprofen described in this study occurred at the level of the spinal cord. Using statistical methods developed for the analysis of drug–drug interactions (Tallarida et al., 1997), current data demonstrated synergism for the depression of both the low-intensity and the high-intensity epsps. By decreasing the concentrations of ketamine and ketoprofen, an equal depressive effect (40% MPE) was obtained compared with higher concentrations of each drug alone. In fact, only about one-third of the calculated concentrations were necessary to achieve 40% MPE in the actual experiments (Figures 3c and e; Table 1). Recently, a more elegant methodology than the one used here to calculate equi-effective concentrations of drugs whose slopes are not parallel has been developed (Tallarida, 2006, 2007). The authors were unaware of this methodology at the time of carrying out the experiments, but it will certainly be useful in future trials to further our understanding of multiple drug action.

These spinal antinociceptive synergistic interactions between ketamine and ketoprofen could have important clinical implications. This is especially so if the side effects of these drugs do not overlap or do not facilitate each other. Interestingly, the depressive actions of ketamine alone on the MSR were significantly reduced when combined with ketoprofen (Figure 3a; Table 1). The MSR is dependent on AMPA and kainate receptor activation (Long et al., 1990; Woodley and Kendig, 1991), and depression of this reflex may be interpreted as a local anaesthetic effect (Lizarraga et al., 2006). In fact, ketamine is known to produce local anaesthetic effects, manifested as motor impairment when administered by the i.t. route (Iida et al., 1997). Thus, the sub-additive effect of the combination ketamine plus ketoprofen could imply a potential to produce a reduction in side effects compared to ketamine alone.

Whether a spinal synergistic antinociceptive interaction with reduced potential side effects between ketamine and ketoprofen also occurs in vivo needs to be addressed, as well as the mechanism(s) by which these interactions take place. An interaction at the level of the Ca2+ activation of phospholipase A2 and subsequent activation of the AA/COX pathway has been proposed for NMDA receptor antagonists and NSAIDs (Price et al., 1996). However, other or additional mechanisms may have contributed to the depressant actions between ketamine and ketoprofen, as in vitro inhibition of COX-1 and COX-2 activity by 50% required only 0.047 and 2.9 μM of ketoprofen, respectively (Warner et al., 1999), and the IC40 values for ketoprofen alone were 368 μM for the high-intensity epsp and 568 μM for the low-intensity epsp. These values are in fact close to those needed by ketoprofen (650 μM) to inhibit the activity of fatty acid amidohydrolase by 50% in rat brains (Fowler et al., 1997). This enzyme is responsible for the breakdown of the endocannabinoid anandamide, which produced antihyperalgesia when injected intrathecally to rats submitted to a model of peripheral inflammatory pain (Richardson et al., 1998). In fact, a spinal endocannabinoid-dependent analgesic effect has been demonstrated for the NSAIDs flurbiprofen and indomethacin (Gühring et al., 2002; Ates et al., 2003).

Using visual analogue scales and post-operative opioid consumption, the analgesic interaction of dextromethorphan and NSAIDs has been studied in human beings. In contrast to the results from the current study, combination of an ineffective oral dose of dextromethorphan (120 mg) with an analgesic oral dose of the NSAID ibuprofen (400 mg) produced no additive or synergistic analgesic effects in patients scheduled for surgical termination of pregnancy (Ilkjær et al., 2000). Similarly, pre-incisional administration of an analgesic dose of dextromethorphan (120 mg, i.m.) and the NSAID tenoxicam (40 mg, i.v.) produced no additive or synergistic analgesia in patients scheduled for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Yeh et al., 2004). However, these single dose studies are inappropriate to determine synergism (Yaksh and Malmberg, 1994). Also in contrast to the results presented here, there is anecdotal evidence, presumably obtained using isobolographic analysis, of additive analgesic effects after i.t. delivery of an unspecified NMDA receptor antagonist together with an unspecified COX inhibitor in a paw formalin test in rats (Yaksh and Malmberg, 1994).

Synergism depends not only on the drugs and the effect measured, but also on the fixed-ratio combination and the total dose in the combination, which may explain the different results between the literature and the present study. It would be interesting to establish whether the antinociceptive synergism between ketamine and ketoprofen is specific for these drugs or whether it extends to the NMDA receptor antagonists and the NSAIDs as a drug class interaction.

Ketamine and L-NAME combination

Ketamine and L-NAME acted synergistically to depress the low-intensity epsp at the same time that induced a sub-additive depressive effect on the MSR. These results may suggest that simultaneously blocking NMDA receptors and inhibiting NO production in the spinal cord could be a new strategy to reduce nociceptive transmission. This is the first time that spinal antinociceptive synergism is reported between a NMDA receptor channel blocker and a NOS inhibitor.

A synergistic interaction between ketamine and L-NAME has been described previously, but tadpoles were used as experimental animals and anaesthesia was taken as the end response (Tonner et al., 1997). In the current study, despite L-NAME alone producing no effect on spinal transmission, it reduced by more than 50% the IC40 values for depression of both NMDA receptor-mediated responses when infused together with ketamine, but at this effect level the interaction was synergistic for the low-intensity epsp only. The large 95% CI for the calculated theoretical additive value may have precluded the actual drug combination from reaching statistical significance for the high-intensity epsp. Isobolar analysis using an effect level in the mid-range of the active drug (that is, IC20) may have been practical for reaching synergism easier. However, an effect level of 40% inhibition of the control response, which was achieved by all active drugs (Figure 2), was selected on the hope of being of clinical relevance. Known analgesic drugs such as morphine and clonidine depress nociceptive transmission on the in vitro rat spinal cord preparation by ∼70% of the control responses (Faber et al., 1997).

The mechanisms by which the synergistic interaction between ketamine and L-NAME took place remain to be elucidated. However, as synergism was only observed on the low-intensity epsp, spinal antinociceptive synergism with this drug combination may occur only when NMDA receptors are activated. This may suggest an interaction between the NMDA receptor–NO pathway. Ketamine is a NMDA receptor channel blocker and it would be expected to indirectly decrease NOS activity by reducing the entry of extracellular Ca2+ into the cell (Miyawaki et al., 1997; Gonzales et al., 1999; Rivot et al., 1999). However, there are reports in which ketamine did not affect the activity of NOS (Tobin et al., 1994) and even increased nitrite and nitrate concentrations (Wu et al., 2000) in CNS tissues from adult rats. Assessment of the biochemical activity of NOS during ketamine perfusion onto the in vitro spinal cord preparation may help to clarify this issue.

Whatever the net effect of ketamine on spinal NO production may have been, ketamine depressed nociceptive transmission in the neonatal rat spinal cord most likely by non-competitively blocking the NMDA receptor channel (Brockmeyer and Kendig, 1995; Lizarraga et al., 2006). Although stimulation of NOS with the subsequent production of NO triggered by activation of NMDA receptors plays an important role in the spinal nociceptive processing of information (see Introduction), there are other receptor systems that can also activate the NO pathway. For instance, activation of glutamate receptors other than NMDA receptors can also increase cGMP concentrations in spinal cord slices from neonate rats (Morris et al., 1994) and in cultured cerebellar cortical neurones from fetal rats (Gonzales et al., 1999). In both cases, NOS inhibitors, including L-NAME, blocked the increase in cGMP concentrations (Morris et al., 1994; Gonzales et al., 1999). Therefore, blockade of NMDA receptors and reduction of NO production may be mechanisms by which ketamine and L-NAME synergistically reduced NMDA receptor-mediated transmission on the neonatal rat spinal cord in vitro.

It also remains to be determined whether antinociceptive synergism between ketamine and L-NAME occurs in vivo and extends to other NMDA receptor antagonists and NOS inhibitors. If synergism is demonstrated in these situations, the combination described in this study could have important clinical implications for the control of pain transmission at the spinal cord level.

In contrast to the present study, there are reports suggesting an antagonistic action of L-NAME on the effects of ketamine in the CNS. Wu et al. (2000) observed that i.p. administration of L-NAME (100 mg kg−1) prevented the i.p. ketamine (100 mg kg−1)-induced increase of nitrite and nitrate concentrations in the hippocampus of adult rats. Mueller and Hunt (1998) demonstrated that chronic subcutaneous administration of L-NAME (50 mg kg−1) prevented the anaesthetic effect of ketamine (75 mg kg−1) given intramuscularly to adult rats. Bulutcu et al. (2002) reported that i.p. (10 mg kg−1), but not i.t. (30 μg in 5 μl), administration of a non-antinociceptive dose of L-NAME prevented the antinociceptive action of i.p. (1–10 mg kg−1) and i.t. (10–60 μg in 5 μl) administration of ketamine in models of inflammatory pain in adult mice. Lauretti et al. (2001) even found that transdermal application of the NO generator nitroglycerin increased the analgesic effect of epidurally administered S(+)-ketamine in patients undergoing orthopaedic knee surgery. These data suggest that ketamine may activate the NO pathway to exert its effects in the CNS, which contrasts with the synergistic effect between ketamine and L-NAME described here. Although the differences between the above studies and the present one could be attributed to developmental changes in the CNS, in particular those of spinal NMDA receptors (Kalb et al., 1992) and NOS (Vizzard et al., 1994), it is more likely that these differences may be due to changes in the absorption and distribution of ketamine induced by NO modulating drugs. For instance, systemic administration of L-NAME, in addition to preventing the anaesthetic effect of systemically administered ketamine, reduced by 75 and 36% the plasma and cerebellar tissue concentration of this drug, suggesting an L-NAME-mediated reduction in blood flow to both the site of administration of ketamine and its site(s) of action in the CNS (Mueller and Hunt, 1998).

Surprisingly, and similar to the combination of ketamine and ketoprofen, the combination of ketamine and L-NAME produced a sub-additive effect on the MSR. Although the mechanisms involved in this interaction are not known, it may appear that depression of the MSR by ketamine is dependent on NO. Again, assessment of ketamine on NOS biochemical activity on the in vitro rat spinal cord may help to explain this. Nonetheless, the sub-additive effect of the combination of ketamine and L-NAME could potentially produce less motor impairment than ketamine alone, making this drug combination as a possible important analgesic combination with reduced side effects.

Ketoprofen and L-NAME combination

Various studies have investigated a possible interaction at the spinal cord level between the NO pathway and the analgesic effects induced by NSAIDs, but there is lack of consistency among them. NSAID-mediated analgesia was reduced (Björkman et al., 1996; Lorenzetti and Ferreira, 1996; Lozano-Cuenca et al., 2005) or unaffected (Sandrini et al., 2002; Díaz-Reval et al., 2004) either by activating or blocking the NO pathway. Even inclusion of an NO moiety into the structure of NSAIDs, including S(+)-ketoprofen, produced enhanced analgesia in comparison to the NSAIDs alone (Gaitan et al., 2004). Discrepancies could be due to the differences in experimental procedures, including the drugs, routes of administration and pain models used.

Using dose–effect experimental designs in models of peripheral inflammatory pain (injection of formalin into the paw) and visceral pain (i.p. administration of acetic acid), Morgan et al. (1992) suggested that synergism occurred in adult mice after i.p. co-administration of L-NAME and the NSAIDs flurbiprofen and indomethacin. Although they provided evidence that subanalgesic doses of both drugs produced analgesia when given together, the authors failed to carry out isobolographic analysis rendering their data as suggestive, but not conclusive. Recently, Dudhgaonkar et al. (2004) used isobolographic analysis to show that the analgesic interaction between the NSAID rofecoxib (selective for COX-2) and the selective inhibitor of the inducible isoform of NOS aminoguanidine was synergistic after oral administration in adult rats submitted to a peripheral inflammatory model of pain (intraplantar formalin). Our data with ketoprofen and L-NAME in the immature spinal cord, which was also obtained using isobolographic analysis, corroborate that the nature of the antinociceptive interaction between NSAIDs and NOS inhibitors is synergistic, and provide evidence that such an interaction can take place at the spinal cord. This is the first report to assess isobolographically, the spinal interaction between a NSAID and a NOS inhibitor.

In contrast to this study, Díaz-Reval et al. (2004) observed lack of effect of intrathecally administered L-NAME on the analgesia induced by S(+)-ketoprofen given orally to arthritic adult rats, and Lozano-Cuenca et al. (2005) reported the need of a functional spinal NO pathway for the NSAID lumiracoxib to induce antihyperalgesia after being injected intrathecally to adult rats submitted to a paw formalin test. It may be possible that in vitro and in vivo data do not correlate well or that experimental procedures (that is, drugs, nociceptive models) affect the outcome of the interaction. Further investigation is necessary to clarify these issues.

The mechanism of the synergistic interaction between ketoprofen and L-NAME is clearly of interest, but cannot be established by the present data. However, as synergism was detected only on the C-fibre-mediated reflex and drugs were applied in known concentrations in the superfusate allow us to formulate some hypotheses. The low-intensity epsp has NMDA receptor components and the high-intensity epsp also has neuropeptide components (Woodley and Kendig, 1991; Faber et al., 1997). As ketoprofen alone depressed both reflexes, antinociception may have been mediated through inhibition of the NMDA neurokinin-1 (NK-1) and calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor systems, as has been shown with other NSAIDs (Malmberg and Yaksh, 1992). However, for the synergistic interaction between ketoprofen and L-NAME, a further inhibition of neuropeptide receptor systems may be possible. Reduction of glutamate, substance P (the endogenous agonist of NK-1 receptors) and calcitonin gene-related peptide release by NSAIDs and NOS inhibitors has been demonstrated (Kawamata and Omote, 1999; Yaksh et al., 2001) and this could also be the case for ketoprofen and L-NAME. The mechanisms for these effects could include inhibition of PG production by ketoprofen (PGs increase the release of glutamate, substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide; Andreeva and Rang, 1993; Bezzi et al., 1998; Southall and Vasko, 2001) and of NO synthesis by L-NAME (NO increased the release of glutamate and substance P; Aimar et al., 1998; Kawamata and Omote, 1999). However, as mentioned before, mechanisms other than, or complementary to, COX inhibition have to be considered. It may be possible that they act on different effector systems in presynaptic neurones or that they interact with each other's pathways (‘crosstalk') (Sakai et al., 1998; Gühring et al., 2000; Bhat et al., 2007).

In conclusion, using isobolographic analysis, the current study provided support for a synergistic interaction between ketamine, ketoprofen and L-NAME combinations to depress nociceptive transmission on an in vitro neonatal rat spinal cord preparation. In addition, combinations in which ketamine was a part were sub-additive to depress the MSR, which may cause less motor impairment than with ketamine alone. Drug combinations are widely used clinically and, if combination profiles such as those shown between the drugs tested here also occurs in vivo, our present findings raise the possibility of ultimate therapeutic exploitation of increased analgesia with fewer side effects.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a grant from the IVABS Postgraduate Research Fund. IL was the recipient of a DGAPA-UNAM Scholarship.

Abbreviations

- AA

arachidonic acid

- epsp

excitatory postsynaptic potential

- IC40

inhibitory concentration at 40% depression of maximal possible effect

- i.t.

intrathecal

- L-NAME

Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester

- MSR

monosynaptic reflex

- NK-1

neurokinin-1

- NSAIDs

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PG

prostaglandin

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Aimar P, Pasti L, Carmignoto G, Merighi A. Nitric oxide-producing islet cells modulate the release of sensory neuropeptides in the rat substantia gelatinosa. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10375–10388. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10375.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akagi H, Konishi S, Otsuka M, Yanagisawa M. The role of substance P as a neurotransmitter in the reflexes of slow time courses in the neonatal rat spinal cord. Br J Pharmacol. 1985;84:663–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb16148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva L, Rang HP. Effect of bradikinin and prostaglandins on the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide-like immunoreactivity from the rat spinal cord in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;108:185–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashina M, Lassen LH, Bendtsen L, Jensen R, Olesen J. Effect of inhibition of nitric oxide synthase on chronic tension-type headache: a randomised crossover trial. Lancet. 1999;353:287–289. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)01079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ates M, Hamza M, Seidel K, Kotalla CE, Ledent C, Gühring H. Intrathecally applied flurbiprofen produces an endocannabinoid-dependent antinociception in the rat formalin test. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:597–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ. Update on the neurophysiology of pain transmission and modulation: Focus on the NMDA-receptor. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:S2–S6. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benrath J, Scharbert G, Gustorff B, Adams HA, Kress HG. Long-term intrathecal S(+)-ketamine in a patient with cancer-related neuropathic pain. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:247–249. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzi P, Carmignoto G, Pasti L, Vesce S, Rossi D, Rizzini BL, et al. Prostaglandins stimulate calcium-dependent glutamate release in astrocytes. Nature. 1998;391:281–285. doi: 10.1038/34651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat A-S, Tandan SK, Kumar D, Krishna V, Prakash VR. Interactions between inhibitors of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase in adjuvant-induced arthritis in female albino rats: an isobolographic study. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;556:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkman R, Hallman KM, Hedner J, Hedner T, Henning M. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug modulation of behavioral responses to intrathecal N-methyl-D-aspartate, but not to substance P and amino-methyl-isoxazole-propionic acid in the rat. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36:20S–26S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmeyer DM, Kendig JJ. Selective effects of ketamine on amino acid-mediated pathways in neonatal rat spinal cord. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:79–84. doi: 10.1093/bja/74.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulutcu F, Dogrul A, Gü MO. The involvement of nitric oxide in the analgesic effects of ketamine. Life Sci. 2002;71:841–853. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01765-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channey MA. Side effects of intrathecal and epidural opioids. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:891–903. doi: 10.1007/BF03011037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoghel JC. Small intrathecal doses of lysine-acetylsalicylate relieve intractable pain in man. J Int Med Res. 1983;11:90–91. doi: 10.1177/030006058301100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Reval MI, Ventura-Martínez R, Déciga-Campos M, Terrón JA, Cabré F, López-Muñoz FJ. Evidence for a central mechanism of action of S-(+)-ketoprofen. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;483:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickenson AH. Spinal cord pharmacology of pain. Br J Anaesth. 1995;75:193–200. doi: 10.1093/bja/75.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan S, Nolan AM. N-methyl D-aspartate induced mechanical allodynia is blocked by nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Neuroreport. 1999;10:449–452. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199902250-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudhgaonkar SP, Kumar D, Naik A, Devi AR, Bawankule DU, Tandan SK. Interaction of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in formalin-induced nociception in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;492:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenach JC, Curry R, Hood DD, Yaksh TL. Phase I safety assessment of intrathecal ketorolac. Pain. 2002;99:599–604. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber ES, Chambers JP, Brugger F, Evans RH. Depression of A and C fibre-evoked segmental reflexes by morphine and clonidine in the in vitro spinal cord of the neonatal rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:1390–1396. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks CA, Schreiber KL, Brewer KL, Yu C-G, Stone LS, Kitto KF, et al. Agmatine reverses pain induced by inflammation, neuropathy, and spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10584–10589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CJ, Tiger G, Stenström A. Ibuprofen inhibits rat brain deamidation of anandamide at pharmacologically relevant concentrations. Mode of inhibition and structure–activity relationship. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:729–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaitan G, Ahuir FJ, Del Soldato P, Herrero JF. Comparison of the antinociceptive activity of two new NO-releasing derivatives of the NSAID S-ketoprofen in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:533–540. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales JM, Loeb AL, Reichard PS, Irvine S. Ketamine inhibits glutamate-, N-methyl-D-aspartate-, and quisqualate-stimulated cGMP production in cultured cerebral neurons. Anesthesiology. 1999;82:205–213. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199501000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gühring H, Görig M, Ates M, Coste O, Zeilhofer HU, Pahl A, et al. Suppressed injury-induced rise in spinal prostaglandin E2 production and reduced early thermal hyperalgesia in iNOS-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6714–6720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06714.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gühring H, Hamza M, Sergejeva M, Ates M, Kotalla CE, Ledent C, et al. A role for endocannabinoids in indomethacin-induced spinal antinociception. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;454:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Joules C, Stanley C, Thomas P, Clarke RW. Glutamate and tachykinin receptors in central sensitization of withdrawal reflexes in the decerebrated rabbit. Exp Physiol. 2004;89:187–198. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2003.002646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth C, Serpell M. Intrathecal anesthesia with ketamine. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23:283–288. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(98)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida H, Dohi S, Tanahashi T, Watanabe Y, Takenaka M. Spinal conduction block by intrathecal ketamine in dogs. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:106–110. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199707000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilkjær S, Nielsen PA, Bach LF, Wernberg M, Dahl JB. The effect of dextromethorphan, alone or in combination with ibuprofen, on postoperative pain after minor gynaecological surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:873–877. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalb RG, Lidow MS, Halsted MJ, Hockfield S. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors are transiently expressed in the developing spinal cord ventral horn. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8502–8506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata T, Omote K. Activation of spinal N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors stimulates a nitric oxide/cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate/glutamate release cascade in nociceptive signaling. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1415–1424. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199911000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauretti GR, Oliveira AP, Rodrigues AM, Paccola CA. The effect of transdermal nitroglycerin on spinal S(+)-ketamine antinociception following orthopedic surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2001;13:576–581. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(01)00333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw WJ, Stephens RL, Binns BC, Chu Y, Sepkuty JP, Johns RA, et al. Spinal glutamate uptake is critical for maintaining normal sensory transmission in rat spinal cord. Pain. 2005;115:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizarraga I, Chambers JP, Johnson CB. Depression of NMDA-receptor-mediated segmental transmission by ketamine and ketoprofen, but not L-NAME, on the in vitro neonatal rat spinal cord preparation. Brain Res. 2006;1094:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizarraga I, Chambers JP, Johnson CB. Developmental changes in threshold, conduction velocity, and depressive action of lignocaine on dorsal root potentials from neonatal rats are associated with maturation of myelination. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85:251–263. doi: 10.1139/y07-021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizarraga I, Chambers P, Johnson CB.Synergistic depression of nociceptive responses by ketoprofen and L-NAME in the neonatal rat hemisected spinal cord preparation Abstracts 11th World Congress on Pain 2005IASP Press: Seattle; 21–26 August, 2005, Sydney, Australia, p 249 (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Long SK, Smith DA, Siarey RJ, Evans RH. Effect of 6-cyano-2,3-dihydroxy-7-nitro-quinoxaline (CNQX) on dorsal root-, NMDA-, kainate- and quisqualate-mediated depolarization of rat motoneurones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;100:850–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti BB, Ferreira SH. Activation of the arginine-nitric oxide pathway in primary sensory neurons contributes to dipyrone-induced spinal and peripheral analgesia. Inflamm Res. 1996;45:308–311. doi: 10.1007/BF02280997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Cuenca J, Castañeda-Hernández G, Granados-Soto V. Peripheral and spinal mechanisms of antinociceptive action of lumiracoxib. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;513:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg AB, Yaksh TL. Hyperalgesia mediated by spinal glutamate or substance P receptor blocked by spinal cycooxygenase inhibition. Science. 1992;257:1276–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.1381521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki I, Nakamura K, Yokubol B, Kitamura R, Mori K. Suppression of cyclic guanosine monophosphate formation in rat cerebellar slices by propofol, ketamine and midazolam. Can J Anaesth. 1997;44:1301–1307. doi: 10.1007/BF03012780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CV, Babbedge RC, Gaffen Z, Wallace P, Hart SL, Moore PK. Synergistic anti-nociceptive effect of L-NG-nitro arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) and flurbiprofen in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;106:493–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R, Southam E, Gittins SR, de Vente J, Garthwaite J. The NO–cGMP pathway in neonatal rat dorsal horn. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:876–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller RA, Hunt R. Antagonism of ketamine-induced anesthesia by an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis: a pharmacokinetic explanation. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;60:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AH, Jamshed HS, Izenwasser S, Heller B, Mattson M, Tortella FC. Highly selective sigma1 ligands based on dextromethorphan. Med Chem Res. 1996;6:102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Park YH, Shin CY, Lee TS, Huh IH, Sohn UD. The role of nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 on the hyperalgesia induced by excitatory amino acids in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2000;52:431–436. doi: 10.1211/0022357001774039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porreca F, Jiang Q, Tallarida RJ. Modulation of morphine antinociception by peripheral [Leu5]enkephalin: a synergistic interaction. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;179:463–468. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90190-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DD, Mao J, Lu J, Caruso FS, Frenk H, Mayer DJ. Effects of the combined oral administration of NSAIDs and dextromethorphan on behavioral symptoms indicative of arthritic pain in rats. Pain. 1996;68:119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JD, Aanonsen L, Hargreaves KM. Antihyperalgesic effects of spinal cannabinoids. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;345:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01621-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivot JP, Sousa A, Montagne-Clavel J, Besson JM. Nitric oxide (NO) release by glutamate and NMDA in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord: an in vivo electrochemical approach in the rat. Brain Res. 1999;821:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai M, Minami T, Hara N, Nishihara I, Kitade H, Kamiyama Y, et al. Stimulation of nitric oxide release from rat spinal cord by prostaglandin E2. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:890–894. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandrini G, Tassorelli C, Cecchini AP, Alfonsi E, Nappi G. Effects of nimesulide on nitric oxide-induced hyperalgesia in humans: a neurophysiological study. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;450:259–262. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southall MD, Vasko MR. Prostaglandin receptor subtypes, EP3C and EP4, mediate the prostaglandin E2-induced cAMP production and sensitization of sensory neurons. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16083–16091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ. Drug Synergism and Dose–Effect Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall, CRC: Boca Raton, FL; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ. An overview of drug combination analysis with isobolograms. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 2006;319:1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ. Interactions between drugs and occupied receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ, Stone DJ, Raffa RB. Efficient designs for studying synergistic drug combinations. Life Sci. 1997;61:PL417–PL425. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)01030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SWN, Babbedge R, Levers T, Dray A, Urban L. No evidence for contribution of nitric oxide to spinal reflex activity in the rat spinal cord in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1995;188:121–124. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11412-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin JR, Martin LD, Breslow MJ, Traystman RJ. Selective anesthetic inhibition of brain nitric oxide synthase. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:1264–1269. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199411000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonner PH, Scholz J, Lamberz L, Schlamp N, Schulte am Esch J. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase decreases anesthetic requirements of intravenous anesthetics in Xenopus laevis. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1479–1485. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199712000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzard MA, Erdman SL, Forstermann U, De Groat WC. Ontogeny of nitric oxide synthase in the lumbosacral spinal cord of the neonatal rat. Dev Brain Res. 1994;81:201–217. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner TD, Giuliano F, Vojnovic I, Bukasa A, Mitchell JA, Vane JR. Nonsteroid drug selectivities for cyclo-oxygenase-1 rather than cyclo-oxygenase-2 are associated with human gastrointestinal toxicity: a full in vitro analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7563–7568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willingale HL, Gardiner NJ, McLymont N, Giblett S, Grubb BD. Prostanoids synthesized by cyclo-oxygenase isoforms in rat spinal cord and their contribution to the development of neuronal hyperexcitability. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:1593–1604. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills RJ, Martin KS. Dextromethorphan/dextrorphan disposition in rat plasma and brain. Pharm Res. 1988;5:S-193. [Google Scholar]

- Woodley SJ, Kendig JJ. Substance P and NMDA receptors mediate a slow nociceptive ventral root potential in neonatal rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1991;559:17–21. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90281-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Kikuchi T, Wang Y, Sato K, Okumura F. NOx- concentrations in the rat hippocampus and striatum have no direct relationship to anaesthesia induced by ketamine. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:183–189. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Dirig DM, Conway CM, Svensson C, Luo ZD, Isakson PC. The acute antihyperalgesic action of nonsteroidal, anti-inflammatory drugs and release of spinal prostaglandin E2 is mediated by the inhibition of constitutive spinal cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) but not COX-1. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5847–5853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05847.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Malmberg AB.Interaction of spinal modulatory receptor systems Progress in Pain Research and Management 19941IASP Press: Seattle, WA; 151–171.In: Fields HL, Liebeskind JC (eds). [Google Scholar]

- Yeh C, Wu C, Lee M, Yu J, Yang C, Lu C, et al. Analgesic effects of preincisional administration of dextromethorphan and tenoxicam following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48:1049–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]