Abstract

Background and purpose:

The n-hexane extracts of the roots of three medicinally used Echinacea species exhibited cytotoxic activity on human cancer cell lines, with Echinacea pallida found to be the most cytotoxic. Acetylenes are present in E. pallida lipophilic extracts but essentially absent in extracts from the other two species. In the present study, the cytotoxic effects of five compounds, two polyacetylenes (namely, 8-hydroxy-pentadeca-(9E)-ene-11,13-diyn-2-one (1) and pentadeca-(9E)-ene-11,13-diyne-2,8-dione (3)) and three polyenes (namely, 8-hydroxy-pentadeca-(9E,13Z)-dien-11-yn-2-one (2), pentadeca-(9E,13Z)-dien-11-yne-2,8-dione (4) and pentadeca-(8Z,13Z)-dien-11-yn-2-one (5)), isolated from the n-hexane extract of E. pallida roots by bioassay-guided fractionation, were investigated and the potential bioavailability of these compounds in the extract was studied.

Experimental approach:

Cytotoxic effects were assessed on human pancreatic MIA PaCa-2 and colonic COLO320 cancer cell lines. Cell viability was evaluated by the WST-1 assay and apoptotic cell death by the cytosolic internucleosomal DNA enrichment and the caspase 3/7 activity tests. Caco-2 cell monolayers were used to assess the potential bioavailability of the acetylenes.

Key results:

The five compounds exhibited concentration-dependent cytotoxicity in both cell types, with a greater potency in the colonic cancer cells. Apoptotic cell death was found to be involved in the cytotoxic effect of the most active, compound 5. Compounds 2and 5were found to cross the Caco-2 monolayer with apparent permeabilities above 10 × 10−6 cm s−1.

Conclusions and implications:

Compounds isolated from n-hexane extracts of E. pallida roots have a direct cytotoxicity on cancer cells and good potential for absorption in humans when taken orally.

Keywords: Echinacea, acetylenes, cancer, MIA PaCa-2, COLO320, Caco-2, permeability, cytotoxicity

Introduction

Echinacea is one of the most popular medicinal herbs and today Echinacea products are among the best-selling herbal preparations in the industrialized world. The genus Echinacea (Asteraceae family) consists of nine species of which only three are traditionally used in medicine: Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench, E. angustifolia (DC.) Hell. and E. pallida (Nutt.) Nutt.

Echinacea has a long history of medicinal use for the treatment of the common cold, upper respiratory infections and a number of other disease conditions (Barnes et al., 2005). An extremely complex chemical composition has been observed in the Echinacea genus, including caffeic acid derivatives (Cheminat et al., 1988; Pellati et al., 2004, 2005), alkamides, acetylenes (polyacetylenes and polyenes) (Bauer et al., 1988a; Bauer and Remiger, 1989; Pellati et al., 2007), polysaccharides (Wagner et al., 1988) and glycoproteins (Classen et al., 2000; Thude and Classen, 2005), all of which exhibit diverse pharmacological activities. Recent attention has focused particularly on alkamides that are lipophilic constituents with cannabinomimetic activity (Woelkart et al., 2005; Raduner et al., 2006), interaction with the immune system (Gertsch et al., 2004) and good bioavailability following oral administration in human (Matthias et al., 2005). In contrast, little information is available about the activity of the acetylenic compounds from Echinacea.

We have recently reported the potential for anticancer activity by Echinacea extracts related to the in vitro cytotoxic and pro-apoptotic properties of n-hexane root extracts from the three medicinally important Echinacea species (Chicca et al., 2007). A more pronounced cytotoxic effect for E. pallida root extracts was observed. This correlates with the different chemical profile of the lipophilic constituents in each of the species, with E. purpurea and E. angustifolia having alkamides as the main lipophilic constituents (Bauer et al., 1988a, 1988b, 1989; Bauer and Remiger, 1989), whereas E. pallida contains polyacetylenes and polyenes (Pellati et al., 2007).

More than 1000 acetylenic molecules have been isolated from plants, fungi, microorganisms and marine invertebrates and identified. The biological activities of acetylenes and related compounds have been studied intensively in recent years and their activity in various organisms is now well documented (Dembitsky, 2006). Polyacetylenes of different sources have been proven to be cytotoxic against different types of cancer cell lines (Matsunaga et al., 1990; Lim et al., 1999; Ito et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2004; Whelan and Ryan, 2004; Zidorn et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2006; Park et al., 2006) and to enhance the cytotoxic activity of other anticancer drugs (Matsunaga et al., 1994).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the cytotoxic activity of polyacetylenes and polyenes from E. pallida roots, isolated through bioassay-guided fractionation, on two human cancer cell lines, the adenocarcinoma MIA PaCa-2 (human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line) and the colonic cell line, COLO320 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line). The potential bioavailability of the E. pallida lipophilic compounds was also investigated using Caco-2 (human colon carcinoma epithelial cell line) cell monolayers.

Materials and methods

Drugs and plant material

5-Fluorouracil was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy). Authentic dried roots (1 kg) of 3-year-old E. pallida (Nutt.) Nutt. were purchased from Planta Medica s.r.l., Pistrino, Perugia, Italy, in January 2005. A voucher specimen was deposited at the Herbarium of the Botanical Garden of the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia (Italy). The plant material was kept in the dark, protected from high temperature and humidity, until required for extraction. The roots were ground with an IKA M20 grinder immediately before extraction.

An alkamide containing Echinacea extract (Echinacea Premium Liquid) was obtained from MediHerb Pty Ltd (Warwick, Australia) and used as a reference in the bioavailability studies as it had been previously shown to possess both bioavailable and non-bioavailable compounds (Matthias et al., 2004).

Extraction and isolation of compounds

Powdered dried roots of E. pallida (1 kg) were extracted in a Soxhlet apparatus for 24 h using n-hexane (5.4 l). The extract was evaporated to dryness under vacuum to give a yellow oil (8 g). The extract was subjected to silica gel column chromatography, affording 155 fractions. Each fraction was analysed by TLC and reversed phase-HPLC, and combined into 10 fractions according to their chromatographic profile. From these fractions, the purified compounds (1–5) (Figure 1) were isolated by silica gel column chromatography and preparative TLC. The structures of the compounds were determined on the basis of UV, IR, NMR (including 1D and 2D NMR experiments, such as 1H–1H gCOSY, gHSQC-DEPT, gHMBC, gNOESY) and MS spectroscopic data (Pellati et al., 2006). Purified compounds were stored under argon at low temperature (−20 °C), protected from light and humidity.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the compounds isolated from E. pallida roots.

Sample preparation for bioavailability study

Powdered dried roots of E. pallida (40 g) were extracted in a Soxhlet apparatus for 4 h using n-hexane (200 ml). The extract was evaporated to dryness under vacuum to give a yellow oil (400 mg). The crude extract was stored under argon at low temperature (−20 °C), protected from light and humidity.

Cell lines and culture

MIA PaCa-2, COLO320, Caco-2 and the human embryonic kidney HEK-293 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). MIA PaCa-2 and HEK-293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with L-glutamine (2 mM), 10% fetal bovine serum, 2.5% horse serum, 50 IU ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). COLO320 were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with L-glutamine (2 mM), 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 IU ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Caco-2 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% non-essential amino acids as previously described (Matthias et al., 2004). All four cell lines were maintained at 37 °C in humidified incubator under 5% CO2. Cell plates and transwell polycarbonate inserts were from Costar (Cambridge, MA, USA). Cell culture reagents were purchased from Gibco-BRL (Gran Island, NY, USA).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Proliferation Reagent WST-1 (4-[3-(4-iodophenyl)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-5-tetrazolio]-1,3-benzene disulphonate) (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) based on the cellular cleavage of the WST-1 to formazan. Cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 103 per well and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After 24 h incubation to allow cell attachment, cells were treated for 72 h with the acetylenic compounds in the range 0.1–100 μM. At the end of the exposure time, WST-1 was added at 1/10 of the total volume and after 60 min of incubation at 37 °C, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader (Wallac; PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA, USA).

Inhibition of cell viability was assessed as the percentage reduction of ultraviolet absorbance of treated cells versus control cultures (vehicle-treated cells) and the 50% inhibitory concentration of cell growth (IC50) was calculated by nonlinear least squares curve fitting (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Each value was obtained from three independent experiments carried out in triplicate.

Caspase 3/7 activity assay

Caspase 3/7 activities were assayed by the Apo-ONE Homogeneous Caspase-3/7 Assay kit (Promega, Milan, Italy), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were plated onto 96-well plates (6 × 103 per well) in the presence of E. pallida compounds 1–5 for 24 h. After cell lysis, the caspase 3/7 assay substrate ((Z-DEVD)2-Rhodamine 110) was added and the fluorescence measured (Wallac; PerkinElmer) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 530 nm, respectively. Values were expressed as the ratio between fluorescent signals generated in cells treated with the compounds and those produced in vehicle-treated cells. Each value was obtained from three independent experiments carried out in triplicate.

DNA fragmentation assay

The occurrence of the nuclear DNA fragmentation was assessed by the Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS kit (Roche), which qualitatively and quantitatively detects the amount of cleaved DNA/histone complexes (nucleosomes) by using a sandwich-enzyme-immunoassay-based method. Briefly, after treatment with the E. pallida compounds 1–5 for 24 h, cells were pelleted and the supernatant was carefully removed to analyse necrosis while the cell pellet was lysed to produce nucleosomes. Subsequently, an aliquot of the lysate was transferred to streptavidin-coated microplates, incubated with immunoreagent (containing anti-histone and anti-DNA antibodies) and peroxidase substrate ABTS (2,2-azino-di (3-ethylbenzthiazolin-sulphonate)). The resulting colour development, which was proportional to the amount of nucleosomes captured in the antibody sandwich, was measured spectrophotometrically at 405 nm (Wallac; PerkinElmer). Data were normalized against the control (vehicle-treated cells) and results are presented as the mean from three independent experiments carried out in triplicate.

Diffusion through Caco-2 cell monolayers

Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) of the monolayers was measured using the Millicell-ERS system (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA, USA) before and after transport experiments to determine the integrity of the monolayers.

At the start of the experiments, 100 μl of Hanks balanced salt solution-HEPES containing the test preparation was added to the apical and 600 μl of Hanks balanced salt solution-HEPES was added to the basolateral side of the monolayers. The plates were shaken in a Heifolf Titramax 1000 at 400 r.p.m. at 37 °C throughout the experiment. At 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, 120 and 150 min, the basolateral volume was removed and replaced with fresh Hanks balanced salt solution-HEPES. The apical solution was sampled only at the conclusion of the experiment. Stock solutions were made in DMSO and then diluted in HEPES buffer to give a final concentration of 0.2% DMSO added to the apical side of the monolayers.

Acetylene concentrations in the samples were determined using a Shimadzu gradient HPLC system (Shimadzu LC10AT) coupled to a quadrupole mass spectrometer (Shimadzu 2010-EV) operating in positive ion mode using an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization interface. The mobile phase was a mixture of water (A) and acetonitrile (B), both containing 0.1% formic acid. The elution gradient used was 40–100% B over 25 min, followed by a period of re-equilibration at 40% B prior to the next injection. A Phenomonex C18, 3 μm, 100 mm × 2.00 mm column was used with a solvent flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1. Apparent permeability coefficients (Papp, cm s−1) were determined at 90 min as previously described (Matthias et al., 2004). Three replicates of each test solution were performed.

Computational analysis

The molecular structures of the compounds isolated from E. pallida were built and graphically handled by means of the InsightII package (MSI-Accelrys) (Biosym/MSI, San Diego, CA, USA, 1995). Molecular geometries were optimized through molecular mechanics-based energy minimizations, by using the Discover program (MSI-Accelrys) (Biosym/MSI), where the cff91 force field was selected. To reasonably simulate plausible conformations of the E. pallida compounds in aqueous environment, all the molecular models were solvated by surrounding them with 18-Å radius spheres of water molecules. The hydrated molecules then underwent energy minimization according to the protocol described below: at first 100 interactions, performed by using a steepest descent algorithm, allowed the system energy to rapidly decrease; then a conjugate gradient algorithm was exploited until a pre-imposed convergence criterion was satisfied (maximum derivative less than 0.001 kcal Å−1).

On the conformers obtained for each molecule after optimizations, solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) calculations were performed using the Homology module of InsightII (Biosym/MSI), whereas molecular weights, volumes and ClogP (calculated log octanol/water partition coefficient) were computed (data not shown) with Chem3D Ultra of the ChemOffice program (Cambridge-Soft Corporation). The two enantiomers (R and S) for each racemic mixture (compounds 1 and 2) were considered and their calculated properties were averaged.

Data analysis

Data are presented as mean values±s.e. The statistical significance of the differences between means was evaluated by Student's t-test for unpaired data. P<0.05 was taken to be significant.

Results

Cytotoxic activity of polyacetylenes and polyenes from E. pallida roots

Compounds 1–5 caused a significant concentration-dependent decrease in MIA PaCa-2 and COLO320 cell viability after 72 h exposure, but had no cytotoxic effect against the non-tumour embryonic kidney cells HEK-293. The IC50 values reported in Table 1 show compound 5 to be the most cytotoxic. Moreover, COLO320 appears to be more sensitive than MIA PaCa-2 cells to all the isolated compounds. In this cell line, the IC50 value of compound 5 was significantly lower than that of the reference drug 5-fluorouracil.

Table 1.

IC50 values of the purified compounds isolated from E. pallida roots on MIA PaCa-2 and COLO320 cells, calculated after 72 h exposure

| Compounds |

IC50 (μM), mean±s.e. |

|

|---|---|---|

| MIA PaCa-2 | COLO320 | |

| 1 | >100 | 80.13±2.21 |

| 2 | >100 | 21.77±1.22 |

| 3 | 60.91±0.61 | 25.28±0.55 |

| 4 | 63.53±1.12 | 22.84±2.12 |

| 5 | 32.17±3.98 | 2.34±0.33 |

| 5-FU | 7.42±0.55 | 8.72±0.18 |

Abbreviations: COLO320, human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line; MIA PaCa-2, human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line.

Data are means from three independent experiments each run in triplicate.

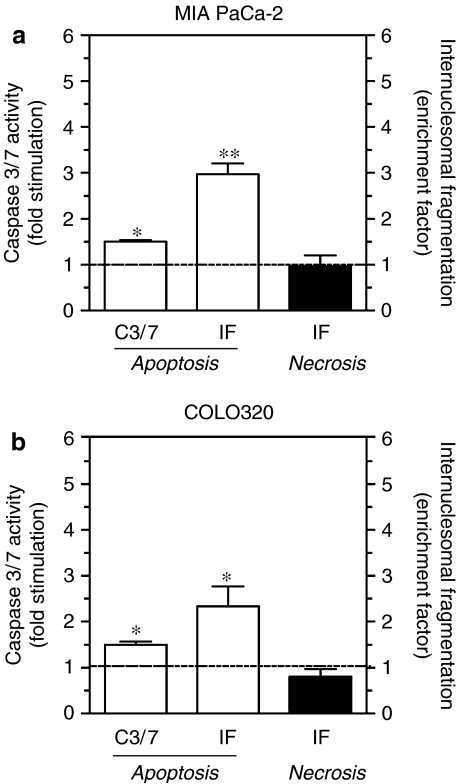

Cell death mechanism involved in compound 5 cytotoxicity

To gain insights into the mechanism involved in the cytotoxicity induced by the most active constituent, compound 5, caspase 3/7 activity and the level of cytosolic histone-associated DNA fragments were evaluated. After 24 h of incubation with the IC50 concentrations in MIA PaCa-2 and COLO320, cells respectively, the caspase 3/7 activity significantly increased (1.51±0.05- and 1.47±0.05-fold higher than vehicle-treated cells in MIA PaCa-2 and COLO320 cells, respectively) (Figure 2a). Moreover, the cytosolic internucleosomal DNA fragments were significantly enhanced as well (2.97±0.25- and 2.32±0.45-fold higher than vehicle-treated cells in MIA PaCa-2 and COLO320 cells, respectively). In contrast, no extracellular DNA fragments were detected for both cell lines in this experimental setting (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Apoptotic and necrotic cell death after treatment with compound 5 for 24 h on MIA PaCa-2 (30 μM) (a) and COLO320 (2.5 μM) (b) cells. Caspase 3/7 activity (C3/7) and internucleosomal fragmentation (IF) were expressed as fold stimulation and as enrichment factor of nucleosomal fragments versus untreated cells, respectively. Data are means±s.e. from three independent experiments each run in triplicate. *P<0.05; **P<0.01, versus untreated cells.

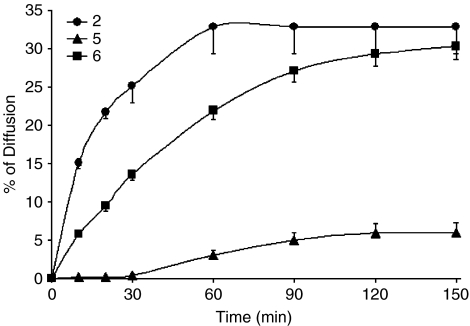

Diffusion of polyacetylenes and polyenes through Caco-2 cell monolayers

The integrity of the Caco-2 monolayers was determined at the beginning and at the end of the experiment. Control TEER values were greater than 500 Ω cm2, indicating that the membranes were intact at all stages of the experiment. TEER values of the monolayers exposed to the E. pallida acetylenes decreased from 560±50 Ω cm2 at the beginning of the experiment to 460±12 Ω cm2 at the end. Some monolayers decreased their TEER values to approximately 200 Ω cm2 but there was no correlation between E. pallida preparation and TEER decreases. To ensure the cells were fully differentiated and confluent, cichoric acid in the Echinacea Premium preparation was used as a negative control as it has been previously shown to have low Papp. Papp for cichoric acid was found to be 0.5 × 10−6 cm s−1, which is in good agreement with previously reported values (Matthias et al., 2004).

Of the acetylenes present in the E. pallida extracts (Pellati et al., 2007), only three acetylenes were found to be potentially bioavailable, compounds 2, 5 and the tetradec-(8Z)-ene-11,13-diyn-2-one (compound 6), which was excluded from the cytotoxicity assay as it was present in fractions not indicated as potentially active during the bioassay-guided fractionation. Transport kinetics for the three acetylenes are shown in Figure 3. The three acetylenes readily crossed the Caco-2 monolayers, although their permeability across the monolayer varied greatly. The calculated Papp values are given in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Transport kinetics of acetylenes in the E. pallida root extract through Caco-2 monolayers during a 2.5 h incubation. Values are means±s.e. from three preparations each run in triplicate. Compound 2: 8-hydroxy-pentadeca-(9E,13Z)-dien-11-yn-2-one; compound 5: pentadeca-(8Z,13Z)dien-11-yn-2-one; compound 6: tetradec-(8Z)-ene-11,13-diyn-2-one.

Table 2.

Acetylene permeability across Caco-2 monolayers after 90 min

| Compounds | Apparent permeability ( × 10−6 cm s−1) |

|---|---|

| 2 | 49±7 |

| 5 | 10±3 |

| 6 | 32±3 |

| AA mw=247 | 57±3 |

| AA mw=231 | 158±31 |

| Cichoric acid | 0.48±0.11 |

Abbreviation: Caco-2, human colon carcinoma epithelial cell line.

Data are means±s.e. from three preparations each run in triplicate. (2, 5, 6=acetylenes from E. pallida; alkamides (AA) and cichoric acid were from E. angustifolia and E. purpurea preparation as previously reported (Matthias et al., 2004).

Computational analysis

Due to the small number of compounds, only a quite elemental structure–activity study based on the use of suitable molecular descriptors can be undertaken. Some molecular descriptors related to the size, shape and lipophilicity of the molecules were considered to be more strictly related to the molecular features expected to account for the activity of the analysed compounds: molecular weights, molecular volumes, ClogP and SASA. While the simplest descriptors, such as molecular weights, molecular volumes, ClogP, were not able to explain the trend of the biological activity, more complex descriptors, such as the two contributions of the SASA (SASA polar and nonpolar components as well as combinations of them) showed a trend quite similar to that shown by the experimental activity data (Table 3).

Table 3.

Total SASA and its components calculated for each compound tested on MIA PaCa-2 and COLO320 cells

| Compounds | Total SASA (Å) | Polar SASA (Å) | Nonpolar SASA (Å2) | Nonpolar/polar ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 564.08 | 83.57 | 480.51 | 5.79 |

| 2a | 577.86 | 78.17 | 499.69 | 6.48 |

| 3 | 554.13 | 66.31 | 487.82 | 7.36 |

| 4 | 561.56 | 66.55 | 495.02 | 7.44 |

| 5 | 550.82 | 38.30 | 512.53 | 13.38 |

Abbreviations: COLO320, human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line; MIA PaCa-2, human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line; SASA, solvent-accessible surface area.

For the two enantiomers of each racemic mixture, averaged values are reported.

In particular, when data obtained on MIA PaCa-2 cells were analysed, the polar component of SASA (for images, see Supplementary data) was observed to follow a trend in accordance with the experimental IC50 values. Lower values of polar SASA correspond to lower IC50 values (higher activity). On the other hand, in COLO320 cells, a good correlation was given by the nonpolar component of the SASA and activity: the most active compound (5) showed the highest values of nonpolar SASA, whereas less active compounds showed lower values of this molecular descriptor (Table 3).

Discussion and conclusions

Over 60% of currently used anticancer agents are of natural origin, derived from plants, marine organisms and microorganisms (Cragg and Newman, 2005). Cytotoxicity screening by using in vitro cell culture is a useful tool for the discovery of new potential anticancer agents from natural products. The criteria of cytotoxic activity for the crude extracts, as established by the American National Cancer Institute, is an IC50<30 μg ml−1, which legitimates further investigation on single active constituents (Suffness and Pezzuto, 1990). In a previous study (Chicca et al., 2007), evaluation of the cytotoxicity of the n-hexane extracts from the three medicinally used Echinacea species revealed a suitable average IC50 (28.5 μg ml−1) concentration in two human cancer cell lines for E. pallida extracts. Bioassay-guided fractionation then allowed isolation of five compounds from the E. pallida n-hexane root extract. In agreement with a number of other studies on the activity of acetylenic compounds on different cancer cell lines (Dembitsky, 2006), the E. pallida constituents exhibited a concentration-dependent cytotoxicity against both the pancreatic MIA PaCa-2 and the colonic COLO320 human cancer cell lines. These compounds showed a selectivity effect on cancer cells versus non-tumour cells with an IC50 higher than 100 μM found in cytotoxic assays against HEK-293 cells. Compound 5 was the most active of the investigated compounds with a very low IC50 value particularly in the colonic cell line (approximately 2 μM). For all the tested compounds, greater sensitivity in COLO320 cells was observed, according to the results obtained with the crude lipophilic extracts in our previous work (Chicca et al., 2007). Nonetheless, the results obtained with compound 5 seem to be relevant also in MIA PaCa-2 cells, because of the general low sensitivity of this cell type to therapeutic agents (Yang et al., 2003).

Analysis of the molecular structure of compound 5 indicated only small conformational differences between it and the other compounds, but the balance between polar and nonpolar regions could be of relevance in explaining its greater activity. In fact, in its structure there is a greater prevalence of nonpolar areas. This property may influence its permeability through cell membranes and gives some advantages in interactions with the molecular target(s) of the acetylene. Unfortunately, until now, a clear mechanism of action for this compound could not be described.

Different mechanisms have been suggested for other cytotoxic acetylenic compounds described in the literature. For example, nonspecific injury to the cytoplasmic membrane, nuclear envelope and mitochondria of L1210 cells by the polyacetylenes of Panax ginseng has been reported, with a minor activity by the relatively polar panaxytriol (Kim et al., 1988). On the other hand, specific activities, such as inhibition of COX and lipoxygenase enzymes, inhibition of DNA synthesis and NO production, have been suggested (Dembitsky, 2006). Moreover, arrest of cell cycle progression in various phases and apoptosis induction are other potential mechanisms (Kuo et al., 2002; Choi et al., 2006; Dembitsky, 2006; Park et al., 2006).

Induction of apoptosis in cancer cells is one of the useful strategies for anticancer drug development (Hu and Kavanagh, 2003; Hunter et al., 2007). Apoptosis is a cellular mechanism of self-destruction, involved in physiological as well as pathological processes and it can be either spontaneous or induced by exogenous agents among which are many drugs already used in cancer treatment.

The occurrence of an apoptotic pathway responsible for the activity of the polyenic compound 5 isolated from E. pallida was investigated in this study. The activity of caspases 3/7, which are executioners of both the intrinsic (or mitochondrial) and the extrinsic (or death receptor-related) apoptotic pathways (Hunter et al., 2007), as well as the presence of intracytoplasmatic internucleosomal fragments, was significantly enhanced after a 24 h time exposure with compound 5, revealing that its cytotoxic effect is mediated through caspase-dependent apoptosis. The enzymatic assay used for the evaluation of DNA fragmentation, through the investigation on the extracellular compartment, let us verify the absence of necrotic cell death as a primary event involved in cytotoxicity induced by compound 5.

The type of induced cell death was studied only in the early stages (24 h), as, in vitro, the absence of phagocytosis of cells in the late stages of apoptosis may induce them to undergo necrosis (apoptotic necrosis or secondary necrosis).

Compound 5 is likely to be able to have in vivo activity as it was shown in this study to be potentially bioavailable. It was one of three acetylenes in the n-hexane extracts from E. pallida that was able to cross the Caco-2 monolayers, which are an accepted model of intestinal absorption. The Papp of this and the other acetylenes indicates that they should be bioavailable in humans (Artursson and Karlsson, 1991). Total recovery of the acetylenes in the Caco-2 experiments was low (approximately 30%), suggesting that the acetylenes had been metabolized or retained in the cells of the monolayers. This is not unexpected as suicide inhibition of different enzymes by acetylenic structures has been previously reported (Bador and Paris, 1990).

In conclusion, our results demonstrate a direct cytotoxic effect of potentially bioavailable acetylenic compounds from E. pallida roots in two different cancer cell lines. The polyene compound 5, the most potent constituent, revealed a pro-apoptotic mechanism of action and a good potential for absorption in humans when taken orally. These data encourage further investigation to clarify the exact mechanism of action of this polyene.

External data objects

Abbreviations

- ClogP

calculated log octanol/water partition coefficient

- Caco-2

human colon carcinoma epithelial cell line

- COLO320

human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line

- HEK-293

human embryonic kidney cell line

- MIA PaCa-2

human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line

- Papp

apparent permeability

- SASA

solvent-accessible surface area

- TEER

transepithelial electrical resistance

- WST-1

4-[3-(4-iodophenyl)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-5-tetrazolio]-1,3-benzene disulphonate

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Pharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/bjp)

References

- Artursson P, Karlsson J. Correlation between oral drug absorption in humans and apparent drug permeability coefficients in human intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;175:880–885. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91647-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bador P, Paris J. Acetylenic enzyme inhibitors: their role in anticancer chemotherapy. Pharm Acta Helv. 1990;65:305–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J, Anderson LA, Gibbons S, Phillipson JD. Echinacea species (Echinacea angustifolia (DC.) Hell., Echinacea pallida (Nutt.) Nutt., Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench): a review of their chemistry, pharmacology and clinical properties. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2005;57:929–954. doi: 10.1211/0022357056127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Khan IA, Wagner H. TLC and HPLC analysis of Echinacea pallida and Echinacea angustifolia roots. Planta Med. 1988a;54:426–430. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-962489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Remiger P. TLC and HPLC analysis of alkamides in Echinacea drugs1, 2. Planta Med. 1989;55:367–371. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-962030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Remiger P, Wagner H. Alkamides from the roots of Echinacea purpurea. Phytochemistry. 1988b;27:2339–2342. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Remiger P, Wagner H. Alkamides from the roots of Echinacea angustifolia. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:505–508. [Google Scholar]

- Cheminat A, Zawatzky R, Becker H, Brouillard R. Caffeoyl conjugates from Echinacea species: structures and biological activity. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:2787–2794. [Google Scholar]

- Chicca A, Adinolfi B, Martinotti E, Fogli S, Breschi MC, Pellati F, et al. Cytotoxic effects of Echinacea root hexanic extracts on human cancer cell lines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HJ, Yee SB, Park SE, Im E, Jung JH, Chung HY, et al. Petrotetrayndiol A induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in SK-MEL-2 human melanoma cells through cytochrome c-mediated activation of caspases. Cancer Lett. 2006;232:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen B, Witthohn K, Blaschek W. Characterization of an arabinogalactan-protein isolated from pressed juice of Echinacea purpurea by precipitation with the β-glucosyl Yariv reagent. Carbohydr Res. 2000;327:497–504. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg GM, Newman DJ.Plants as a source of anti-cancer agents J Ethnopharmacol 200510072–79.review [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembitsky VM. Anticancer activity of natural and synthetic acetylenic lipids. Lipids. 2006;41:883–924. doi: 10.1007/s11745-006-5044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertsch J, Schoop R, Kuenzle U, Suter A. Echinacea alkylamides modulate TNF-alpha gene expression via cannabinoid receptor CB2 and multiple signal transduction pathways. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Kavanagh JJ. Anticancer therapy targeting the apoptotic pathway. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:721–729. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter AL, Zhang J, Chen SC, Si X, Wong B, Ekhterae D, et al. Apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain (ARC) inhibits myogenic differentiation. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:879–884. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito A, Cui B, Chávez D, Chai HB, Shin YG, Kawanishi K, et al. Cytotoxic polyacetylenes from the twigs of Ochanostachys amentacea. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:246–248. doi: 10.1021/np000484c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Lee YH, Kim SI. A possible mechanism of polyacetylene membrane cytotoxicity. Korean J Toxicol. 1988;4:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo PL, Chiang LC, Lin CC. Resveratrol-induced apoptosis is mediated by p53-dependent pathway in Hep G2 cells. Life Sci. 2002;72:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Hwang WI, Lim ST. Antioxidant and anticancer activities of organic extracts from Platycodon grandiflorum A. De Candolle roots. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YJ, Kim JS, Im KS, Jung JH, Lee CO, Hong J, et al. New cytotoxic polyacetylenes from the marine sponge Petrosia. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:1215–1217. doi: 10.1021/np9900371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga H, Katano M, Saita T, Yamamoto H, Mori M. Potentiation of cytotoxicity of mitomycin C by a polyacetylenic alcohol, panaxytriol. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1994;33:291–297. doi: 10.1007/BF00685902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga H, Katano M, Yamamoto H, Fujito H, Mori M, Takata K. Cytotoxic activity of polyacetylene compounds in Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer. Chem Pharm Bull. 1990;38:3480–3482. doi: 10.1248/cpb.38.3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthias A, Addison RS, Penman KG, Dickinson RG, Bone KM, Lehmann RP. Echinacea alkamide disposition and pharmacokinetics in humans after tablet ingestion. Life Sci. 2005;77:2018–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthias A, Blanchfield JT, Penman KG, Toth I, Lang CS, De Voss JJ, et al. Permeability studies of alkylamides and caffeic acid conjugates from Echinacea using a Caco-2 cell monolayer model. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2004;29:7–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2003.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Kim GY, Kim GD, Lee WH, Cheong JH, Kim ND, et al. Suppression of U937 human monocytic leukemia cell growth by dideoxypetrosynol A, a polyacetylene from the sponge Petrosia sp., via induction of Cdk inhibitor p16 and down-regulation of pRB phosphorylation. Oncol Rep. 2006;16:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellati F, Benvenuti S, Magro L, Melegari M, Soragni F. Analysis of phenolic compounds and radical scavenging activity of Echinacea spp. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2004;35:289–301. doi: 10.1016/S0731-7085(03)00645-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellati F, Benvenuti S, Melegari M, Lasseigne T. Variability in the composition of anti-oxidant compounds in Echinacea species by HPLC. Phytochem Anal. 2005;16:77–85. doi: 10.1002/pca.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellati F, Calò S, Benvenuti S. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of polyacetylenes and polyenes in Echinacea pallida by using a monolithic reversed-phase silica column. J Chromatogr A. 2007;114:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellati F, Calo S, Benvenuti S, Adinolfi B, Nieri P, Melegari M. Isolation and structure elucidation of cytotoxic polyacetylenes and polyenes from Echinacea pallida. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:1359–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raduner S, Majewska A, Chen JZ, Xie XQ, Hamon J, Faller B, et al. Alkylamides from Echinacea are a new class of cannabinomimetics. Cannabinoid type2 receptor-dependent and -independent immunomodulatory effects. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14192–14206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suffness M, Pezzuto JM.Assays related to cancer drug discovery Methods in Plant Biochemistry: Assays for Bioactivity 1990Academic Press: London; 71–133.In: Hostettmann K (ed).vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Thude S, Classen B. High molecular weight constituents from roots of Echinacea pallida: an arabinogalactan-protein and an arabinan. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:1026–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H, Stuppner H, Schafer W, Zenk M. Immunologically active polysaccharides of Echinacea purpurea cell cultures. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Whelan LC, Ryan MF. Effects of the polyacetylene capillin on human tumour cell lines. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:2281–2286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelkart K, Xu W, Pei Y, Makriyannis A, Picone RP, Bauer R. The endocannabinoid system as a target for alkamides from Echinacea angustifolia roots. Planta Med. 2005;71:701–705. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Cao Z, Yan H, Wood WC. Coexistence of high levels of apoptotic signaling and inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in human tumor cells: implication for cancer specific therapy. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6815–6824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zidorn C, Johrer K, Ganzera M, Schubert B, Sigmund EM, Mader J, et al. Polyacetylenes from the Apiaceae vegetables carrot, celery, fennel, parsley, and parsnip and their cytotoxic activities. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:2518–2523. doi: 10.1021/jf048041s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.