Abstract

Rationale: From 1921 to 1990, vermiculite ore from Libby, Montana, was shipped worldwide for commercial and residential use. A 1980 study of a manufacturing facility using Libby vermiculite was the first to demonstrate a small but significant prevalence of pleural chest radiographic changes associated with amphibole fibers contained in the ore.

Objectives: This follow-up study of the original cohort evaluated the extent of radiographic changes and cumulative fiber exposure (CFE) 25 years after cessation of exposure.

Methods: From the original cohort of 513 workers, 431 (84%) were living and available for participation and exposure reconstruction. Of these, 280 (65%) completed both chest radiographs and interviews. Primary outcomes were pleural and/or interstitial changes.

Measurements and Main Results: Pleural and interstitial changes were demonstrated in 80 (28.7%) and 8 (2.9%) participants, respectively. Of those participants with low lifetime CFE of less than 2.21 fiber/cc-years, 42 (20%) had pleural changes. A significant (P < 0.001) exposure–response relationship of pleural changes with CFE was demonstrated, ranging from 7.1 to 54.3% from the lowest to highest exposure quartile. Removal of individuals with commercial asbestos exposure did not alter this trend.

Conclusions: This study indicates that exposure within an industrial process to Libby vermiculite ore is associated with pleural thickening at low lifetime CFE levels. The propensity of the Libby amphibole fibers to dramatically increase the prevalence of pleural changes 25 years after cessation of exposure at low CFE levels is a concern in view of the wide national distribution of this ore for commercial and residential use.

Keywords: vermiculite, pleural disease, amphiboles, fibrosis, mineral fiber

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

It has been previously demonstrated amphibole fibers can cause pleural thickening and interstitial fibrosis related to latency from initial exposure and duration of exposure.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Pleural and interstitial changes can occur at low lifetime cumulative amphibole fiber exposure levels in a dose–response manner.

Vermiculite is a micaceous mineral that expands nearly 20 times its original size when heated (1). The expanded form has insulating and absorbent properties, and has been used in numerous residential and commercial applications (1, 2). From the 1920s to 1990, the Libby, Montana, mine produced up to 80% of the world's vermiculite supply and shipped it to over 200 regional processing facilities (3, 4). In 1979, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimated that 13 million people lived within the vicinity of these facilities and 106 million people were exposed to consumer products containing vermiculite (5).

A cluster of bloody pleural effusions in workers sparked a 1980 study at a facility that was expanding Libby vermiculite for use as an inert carrier for lawn care products (6). This was the first published study to identify health risks from the amphibole fibers contained within the Libby vermiculite ore. Chest radiographic changes (excluding solitary blunting of the costophrenic angle), similar to that found with commercial asbestos exposure, were demonstrated in 2.2% of the overall cohort and 8.4% of the highest cumulative fiber exposure (CFE) group (6).

This follow-up study reevaluated the current chest radiographic status of the original 1980 worker cohort 25 years after their last Libby vermiculite exposure. The objectives were to determine the magnitude of any increased prevalence of chest radiographic changes and to determine the CFE level associated with these changes. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (7).

METHODS

Participants and Interviews

The eligible cohort included the original 512 participants (6) plus 1 additional worker identified from the original records. In 1980, these 513 participants had an average age of 37.5 (range, 16–66) years; 93.8% were male and 96.8% were white. Current data were collected between 2004 and 2005. Each worker received a letter describing the study and signed an informed consent. Those living within 50 miles of the facility completed in-person interviews and chest radiographs at a nearby site. Those who were living farther away completed telephone interviews and obtained chest radiographs from nearby medical facilities. Interviews inquired about pulmonary history and job history since 1980. Potential exposures to regulated commercial asbestos minerals, such as amosite, chrysotile, or crocidolite, were evaluated in the 1980 study for all subjects and again in 2004 for all repeat participants. These data were used in a subanalysis to exclude all those with reported commercial asbestos exposure.

Chest Radiographs

Posteroanterior chest radiographs were classified independently by three board-certified radiologists who are “B” readers using the 2000 International Labor Office International Classification of Radiographs of Pneumoconioses (8). Radiologists were blinded to all identifiers and 10% known normal radiographs from another study were randomly interspersed with the study films. Pleural changes that were considered were localized (pleural plaques) and/or diffuse pleural thickening. Localized pleural thickening was defined as thickening with or without calcification, excluding solitary costophrenic angle blunting (8). Diffuse pleural thickening was pleural thickening, including costophrenic angle blunting, with or without calcification (8). Interstitial changes were defined as irregular opacities, profusion of 1/0 or greater (8). For this analysis, a radiographic reading was defined as positive when the median classification from the three independent B readings was consistent with pleural and/or interstitial changes. Radiographs classified as unreadable were not used. The original chest radiographs from the 1980 study were unavailable.

Environmental Measurement

The company in the original 1980 study began vermiculite expander operations in 1957 and subsequently used Libby vermiculite ore from 1963 to 1980 (9). Initial environmental measurements beginning in 1972 were obtained by collecting airborne fibers on membrane filters at a sample rate of 2 L/minute (6). Particles greater than 5 μm in length, less than 3 μm in diameter, and with an aspect ratio of 3:1 or more were counted as fibers (6). Before 1976, industrial hygienists followed a worker with a sampling device (6), and subsequent levels were obtained by personal breathing zone sampling (6). Fiber exposure differed greatly by department (6).

The primary independent variable was CFE in fiber/cc-years. The reconstructed CFE was calculated using the traditional approach of multiplying the 8-hour time-weighted average (TWA) by the number of years at the TWA summed over all years (6). Objective estimates of total workdays per year were unavailable because of extensive overtime as reported by some workers through worker interviews (6, 9). Due to new environmental controls, there was a decrease in fiber exposure after 1973. Therefore, each department was assigned two values, fiber exposures through 1973 and exposures after 1973 (6). Each participant was assigned a CFE value, which was the summation of estimated fiber exposure by department, based on the years employed between 1963 and 1980.

Evaluating Participation Bias

Participation versus nonparticipation bias for living workers was assessed by comparing age as of July 1, 2004, sex, smoking history (yes/no), hire date (⩽1973, >1973), and CFE. Characteristics of those who participated in 1980 but were deceased before the 2004 study were also assessed. To examine potential participation bias, the initial analysis included all participants and living nonparticipants, assuming the latter had normal chest radiographs.

Because of possible misclassification of historical fiber exposure on or before 1973, analysis was also performed on all participants and living nonparticipants hired after 1973. In addition, results of analyses were also reported for participants and living nonparticipants after excluding those who reported potential commercial asbestos exposure on the basis of their respective 2004 and 1980 interviews.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

For this 25-year follow-up study, questionnaire data were entered directly into the computer during the interview using SAS PROC FSEDIT (Version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and stored as SAS datasets. All radiographic classifications were double entered manually using SAS FSEDIT, and compared using SAS PROC COMPARE to identify data entry errors.

Mean CFE values were compared between those with and without chest radiograph changes using t tests (at least 30 participants per group) and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test (<30 participants per group). CFE was also characterized dichotomously (<1 fiber/cc-years, ⩾1 fiber/cc-years) and by worker-exposure quartiles. To further assess the relationship of pleural changes to CFE, the analysis progressed from univariate and bivariate to multivariate analyses. Cofactors included were as follows: age (40–49, 50–59, ⩾60 yr), smoking history (yes/no), body mass index (BMI), sex, and hire date (⩽1973, >1973). BMI was calculated with height and weight measurements from local screening and categorized in accord with public health recommendations (⩽24.9, 25–29.9, ⩾30 kg/m2) (10). No BMI values were calculated for those who underwent telephone interviews. A trend between pleural changes by quartile and CFE was assessed using the Cochrane Armitage test and two-sided P values. This test was repeated after removal of individuals who reported potential commercial asbestos exposure.

To determine the effect modification of the cofactors with regard to the relationship between CFE and pleural changes, a series of logistic regression models were conducted adding individual cofactors. To evaluate the multicollinearity, PROC REG in SAS and the variance inflation factor (VIF) were used as criteria to detect the presence of any serious collinearity. A VIF greater than 10 indicates serious collinearity, and none of the VIFs of the predictors in these analyses exceeded 5. Furthermore, the effect of our key exposure variable was quite stable regardless of which other predictors were present in the model. Goodness-of-fit was determined using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for pleural changes (yes/no) in each, with the reference category calculated as the CFE below the 25th percentile. By assessing all models and obtaining the ORs for each, the robustness and consistency of CFE effect on the probability of pleural changes were ascertained.

RESULTS

Population

Of the original 1980 cohort (n = 513), 82 (16.0%) were deceased. Of the remaining 431 workers, 298 (69.1%) participated in this study, 55 (12.8%) refused, 70 (16.2%) were located but did not respond, and 8 (1.9%) were not located and were presumed living because they were not found in the National Death Index. Of the 298 participants, 280 (94.0%) had complete interviews and readable chest radiographs, representing 65.0% of the original cohort (431) still alive after 25 years. Of the 280 participants, 274 (97.9%) were white. As shown in Table 1, the participants and nonparticipants were not significantly different in terms of sex or age. Participants, however, were significantly more likely than living nonparticipants to have been hired on or before 1973 (66.4 and 49.7%, respectively), and had significantly higher mean CFE (SD) at 2.48 (4.19) and 1.76 (3.44) fiber/cc-years, respectively. The range in CFE for the two groups was almost identical.

TABLE 1.

DEMOGRAPHICS AND CUMULATIVE FIBER EXPOSURE OF PARTICIPANTS VERSUS NONPARTICIPANTS*

| Participants (n = 280) | Nonparticipants (n = 151)† | Deceased (n = 82) | P Value‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age,§ mean yr (1 SD) | 59.1 (10.5) | 59.4 (11.3) | 74.0 (11.2) | 0.53 |

| Age§ range, yr | 44–87 | 44–86 | 46–91 | — |

| Male sex, n (%) | 264 (94.3) | 137 (90.7) | 80 (97.6) | 0.17 |

| Ever smoked,‖ n (%) | 164 (58.6) | 100 (66.2) | 62 (75.6) | 0.11 |

| Hired before or during 1973, n (%) | 186 (66.4) | 75 (49.7) | 69 (84.2) | 0.001 |

| Mean (1 SD) cumulative amphibole fiber exposure, fiber/cc-years | 2.48 (4.19) | 1.76 (3.44) | 3.31 (4.69) | 0.06 |

| Range of cumulative amphibole fiber exposure, fiber/cc-years | 0.01–19.03 | <0.01–19.02 | <0.01–19.02 | — |

Deceased persons were members of the original 1980 cohort who had death certificates dated before March 2004 when interviewing started.

This group is made up of both nonparticipants and those who did not fully complete the 2004 study: 133 were not located, refused, or did not respond; 11 only completed the interview; and 7 had unreadable chest radiographs.

P value compares participants and living nonparticipants.

Age as of July 1, 2004 (year of interviews), for the original 1980 cohort. For those deceased, this is the age they would be if still living.

Smoking as reported in the 1980 questionnaire.

The distribution of participant CFE by percentiles was 0.28 at the 25th, 0.85 at the 50th, 2.20 at the 75th, and 9.32 CFE at the 90th percentile (data not shown). The highest mean CFE (SD) was in deceased workers at 3.31 (4.69) fiber/cc-years. Hire date, age, and sex in participants were associated with CFE (data not shown). For the 186 participants hired in 1973 or before, the mean CFE of 3.58 (4.77) fiber/cc-years was higher (P < 0.001) compared with 94 hired after 1973 at 0.30 (0.41) fiber/cc-years. Also, there was a significant trend of increasing age with higher CFE (P < 0.001), and the mean CFE of the 16 women was lower (P < 0.001) compared with men.

Pleural Changes

The prevalence of pleural changes for participants was 28.7%, and after combining participants (280) and living nonparticipants (151) it was 18.6%. This latter percentage was derived from the most conservative analytical approach because it assumed that all living nonparticipants had normal radiographs. Comparing the higher exposed quartiles to the reference quartile, Table 2 shows a significant trend (P < 0.001) of increasing pleural changes with increasing CFE. A similar significant trend (P < 0.001) was seen in 368 participants and living nonparticipants after removal of those with potential commercial asbestos exposure (data not shown). Within this latter group, the overall prevalence was 18.7% (69), and changes by exposure quartile of CFE were 4.4% (4), 10.9% (10), 21.7% (20), and 38.0% (35). Crude ORs were significant in the third (CFE range, 0.81–1.99 fiber/cc-years) and fourth (CFE range, 2.00–19.03 fiber/cc-years) exposure quartiles.

TABLE 2.

PREVALENCE OF PLEURAL RADIOGRAPHIC CHANGES* ACCORDING TO QUARTILES OF CUMULATIVE FIBER EXPOSURE IN 280 PARTICIPANTS AND 151 LIVING NONPARTICIPANTS†

| Exposure Quartile | Range of Amphibole Fiber Exposure (fiber/cc-years) | No. of Workers | No. of Workers with Pleural Radiographic Change* (%)‡ | Crude OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 0.005–0.24 | 108 | 4 (3.7) | Reference | — |

| Second | 0.25–0.74 | 108 | 15 (13.9) | 4.19 | 1.34–13.08 |

| Third | 0.75–1.91 | 108 | 20 (18.5) | 5.91 | 1.95–17.93 |

| Fourth | 1.92–19.03 | 107 | 41 (38.3) | 16.15 | 5.53–47.17 |

| Total | 431 | 80 (18.6) |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

The 80 workers with pleural radiographic changes included 68 with localized (85%) and 12 with diffuse pleural thickening (15%).

Assumes nonparticipants have no pleural radiographic changes.

Significant trend, P < 0.001.

No pleural or interstitial changes were noted by any of the radiologists regarding the known normal films from another study that were randomly interspersed with the study films. Also, no additional individuals with a potential commercial asbestos exposure were identified in the 2004 participant interviews that were not previously identified in the original 1980 interviews.

The prevalence of pleural changes in the 280 participants was 28.7%. Of the participants with pleural changes, 64 had localized pleural thickening only, 10 had diffuse pleural thickening only, and 6 had both pleural thickening (4 localized and 2 diffuse) with interstitial changes. Of the 80 participants with pleural changes, 53 (66.3%) were bilateral, 14 (17.5%) unilateral, and 13 (16.3%) split unilateral–bilateral, the latter as classified by two radiologists. The mean time (SD) since initial Libby vermiculite exposure for the 80 participants with pleural changes and the 200 without pleural changes was 36.8 (4.9) years (median, 37.9) and 32.1 (5.5) years (median, 31.0), respectively. Participants with any pleural change (80) had significantly greater (P < 0.001) mean CFE (SD) compared with the 200 participants without pleural changes: 4.77 (5.72) fiber/cc-years (median, 1.99) and 1.56 (2.94) fiber/cc-years (median, 0.62), respectively. Comparing the higher exposed quartiles to the reference quartile, Table 3 shows a significant trend (P < 0.001) of increasing pleural changes with increasing CFE. Of the 252 participants reporting no commercial asbestos exposure, 69 (27.4%) demonstrated pleural changes with a similar significant trend of increasing pleural changes with increasing quartile CFE (P < 0.01), with a prevalence of 6.4% (4), 19.1% (12), 33.3% (21), and 50.8% (32), respectively (data not shown). Crude ORs were significant in the third (CFE range, 0.86–2.37) and fourth (CFE range, 2.38–19.03) exposure quartiles.

TABLE 3.

PREVALENCE OF PLEURAL RADIOGRAPHIC CHANGES* ACCORDING TO QUARTILES OF CUMULATIVE FIBER EXPOSURE IN 280 PARTICIPANTS

| Exposure Quartile | Range of Amphibole Fiber Exposure (fiber/cc-years) | No. of Workers | No. of Workers with Pleural Radiographic Change (%)† | Crude OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 0.01–0.28 | 70 | 5 (7.1) | Reference | — |

| Second | 0.29–0.85 | 72‡ | 17 (24.6) | 4.02 | 1.39–11.60 |

| Third | 0.86–2.20 | 68‡ | 10 (29.4) | 5.42 | 1.90–15.46 |

| Fourth | 2.21–19.03 | 70 | 38 (54.3) | 15.44 | 5.55–42.98 |

| Total | 280 | 80 (28.7) |

The 80 workers with pleural radiographic changes include 68 with localized (85%) and 12 with diffuse pleural thickening (15%).

Significant trend, P < 0.001.

Two observations in the second quartile and two in the third quartile had exact exposure values at the 50th percentile cutoff point. Rounding put these four observations into the second quartile.

An analysis of 94 participants (10 cases) and 75 living nonparticipants hired after 1973 when more comprehensive environmental measurements were available demonstrated a similar trend of increasing pleural changes across increasing exposure quartiles, which was not significant (P = 0.09) due to fewer cases. Within the highest CFE quartile (range, 0.30–2.13), the prevalence was 11.9% (5) with a crude OR of 5.68 (95% CI, 0.63–50.82). Similar trends (P = 0.18) were found after removal of individuals with potential commercial asbestos exposure.

Participants with localized pleural changes only and no reported commercial asbestos exposure (56) had significantly higher (P < 0.01) mean CFE (SD) level compared with the 181 participants with normal chest radiographs and no reported commercial asbestos exposure: 3.45 (4.95) fiber/cc-years (median, 1.52) and 1.55 (2.89) fiber/cc-years (median, 0.62), respectively. Comparing the higher exposed quartiles to the reference quartile, there remained a significant trend (P < 0.001) of increasing localized pleural changes with increasing CFE, with a prevalence of 6.7% (4), 18.6% (11), 28.8% (17), and 40.7% (24) (data not shown). Crude ORs were significant for the third (CFE range, 0.84–1.88) and fourth (CFE range, 1.88–19.03) exposure quartiles.

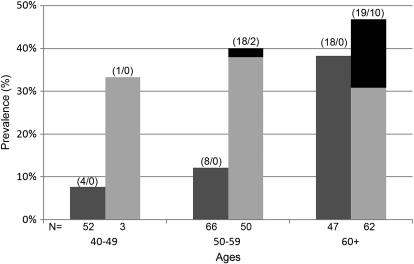

Hire date and age of the participants also were significantly associated with pleural changes (P < 0.001) (Table 4). Participants hired on or before 1973 were more likely to have pleural changes (37.6%) compared with 10.6% for those hired after 1973 (crude OR, 5.07; 95% CI, 2.47–10.41). Furthermore, participants 60 years or older had significantly increased odds of pleural changes compared with those 40 to 49 years old. Also, within both the <1 and ⩾1 fiber/cc-year categories, prevalence of pleural changes increased with age (Figure 1). The highest prevalence in the <1 and ⩾1 fiber/cc-year categories were in the 60+-year-old age groups at 38 and 47%, respectively.

TABLE 4.

PREVALENCE OF PLEURAL RADIOGRAPHIC CHANGES* IN 280 PARTICIPANTS ACCORDING TO VARIOUS COFACTORS

| Variable | No. of Workers | No. of Workers with Radiographic Pleural Changes (%) | Crude OR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hire date | |||||

| Hired on or before 1973 | 186 | 70 (37.6) | 5.07 | 2.47–10.41 | <0.001 |

| Hired after 1973 | 94 | 10 (10.6) | Reference | — | — |

| BMI,† kg/m2 | |||||

| ≤24.9 | 28 | 8 (28.6) | Reference | — | — |

| 25–29.9 | 101 | 31 (30.7) | 1.11 | 0.44–2.79 | 0.52 |

| ≥30 | 110 | 27 (24.5) | 0.81 | 0.32–2.06 | 0.43 |

| Smoking history (ever smoked)‡ | |||||

| Yes | 184 | 55 (29.9) | 1.21 | 0.70–2.11 | 0.50 |

| No | 96 | 25 (26.04) | Reference | — | — |

| Age at time of interview, yr | |||||

| 40–49 | 55 | 5 (9.1) | Reference | — | — |

| 50–59 | 116 | 28 (24.1) | 3.18 | 1.16–8.76 | 0.03 |

| ≥60 | 109 | 47 (43.1) | 7.58 | 2.80–20.49 | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 16 | 1 (6.3) | Reference | — | |

| Male | 264 | 79 (29.9) | 6.40 | 0.83–49.32 | 0.07 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

The 80 workers with pleural radiographic changes included 68 with localized (85%) and 12 with diffuse pleural thickening (15%).

n = 239 for BMI due to 38 persons undergoing phone interview and 3 persons with onsite interviews who were not measured for height and weight.

Smoking history as recorded in 2004 questionnaire. Of these 280 participants, 20 persons reported never smoking in the 1980 questionnaire but subsequently reported a history of smoking in the 2004 questionnaire (either current or ex-smoker).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of pleural radiographic changes including localized and diffuse pleural thickening by age and cumulative fiber exposure (<1 and ⩾fiber/cc-years). Dark gray bars = fiber/cc-years < 1; light gray bars = fiber/cc-years ⩾ 1; black bars = proportion of diffuse pleural thickening. Numbers above bars = localized/diffuse; numbers below bars = total number of participants in each category.

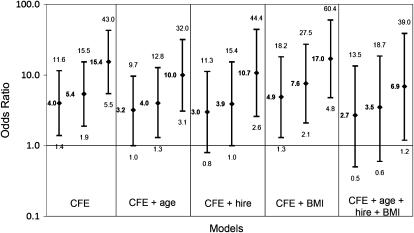

Figure 2 depicts the association between pleural changes in participants and CFE using different regression models. The ORs and 95% CIs are shown for each exposure quartile, with the first quartile as reference. Each model demonstrates the same trend: increasing pleural changes with increasing CFE. Lack of multicollinearity was reflected in the stable results of the modeling, with the exposure–response relationship remaining the same as different models were constructed. No significant interactions were found. Hosmer-Lemeshow, Pearson, and Deviance goodness-of-fit tests for all models indicated that the assumptions were met.

Figure 2.

Association of pleural radiographic changes with cumulative fiber exposure, according to models including various cofactors. BMI = body mass index; CFE = cumulative fiber exposure in quartiles; hire = date of hire. For each model, CFE quartiles 2, 3, and 4 are represented in sequential order. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are represented on a log scale.

Diffuse Pleural Thickening

Among the 80 participants with pleural changes, 12 (15%) demonstrated diffuse pleural thickening, 8 unilateral and 4 bilateral, and 2 of these had concomitant interstitial changes. The mean CFE (SD) for the 10 with diffuse pleural thickening alone was 8.99 (5.16) fiber/cc-years, and was significantly greater (P < 0.001) than in the 198 participants with no radiographic changes at 1.48 (2.78) fiber/cc-years. The mean CFE of these 10 participants was also significantly greater (P < 0.001) than the 64 participants with localized pleural changes alone, which was 3.37 (4.84) fiber/cc-years. Of these 10 participants, removal of 2 participants who reported commercial asbestos exposure resulted in a similar mean CFE of 8.00 (5.32) fiber/cc-years.

Interstitial Changes

Eight (2.9%) participants had interstitial changes versus one (0.2%) participant in the original 1980 study (6). These eight individuals were older (mean age, 78.5 yr; SD, 6.6) and six of eight smoked cigarettes (mean pack-years, 41.1; SD, 28.2). The median profusion scores for each of these eight participants were as follows: 1/0 (for one participant), 1/1 (for three participants), 2/1 (for one participant), 2/2 (for one participant), 2/3 (for one participant), and 3/2 (for one participant). Their mean CFE (SD) of 11.86 (6.46) fiber/cc-years was significantly greater compared with the 198 participants with no radiographic change (P < 0.001), and the 64 with only localized pleural changes (P < 0.001). Of these eight, there were two with diffuse and four with localized pleural thickening, and one reporting commercial asbestos exposure. All eight with interstitial changes occurred at the 72% or greater maximum CFE range, with six occurring at the 90% or greater range. Removal of the one individual with reported commercial asbestos exposure did not appreciably change the mean CFE at 11.37 (6.82) fiber/cc-years.

DISCUSSION

The unprocessed vermiculite ore mined until 1990 in Libby, Montana, contained 0.1 to 26% naturally occurring amphibole fibers (11, 12). Historically, these amphibole fibers were typically characterized as “tremolite” or “soda-tremolite” asbestos (13). Additional characterization with improved technology in conjunction with newer mineral classifications indicates that these fibers vary in chemical composition, including within a single fibrous particle, and are best described in decreasing order of abundance as winchite, richterite, and tremolite (13).

This follow-up study of workers who processed Libby vermiculite ore demonstrates a significant increase in pleural changes, from 2.0% in the 1980 study to 28.7% in 2005 (6). Pleural changes are directly related to CFE, with the greatest prevalence (54.3%) in the highest exposure quartile (range, 2.21–19.03 fiber/cc-years) of participants. Regression models consistently demonstrate an exposure-dependent relationship at low CFE levels. With an additional 25 years after cessation of exposure to Libby vermiculite, the prevalence of pleural changes increased with age, including in those workers with less than 1 fiber/cc-year lifetime CFE as reflected in Figure 1. An increase in interstitial changes was also noted from 0.2% in 1980 to 2.9% in 2005 (6).

These types of radiographic changes are predominantly due to past exposures to commercial asbestos in the workplace. Studies of U.S. populations with no reported asbestos exposures have found a low prevalence of pleural changes, ranging from 0.2 to 1.8% (14, 15). National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) I and II evaluated radiographs from two temporally distinct cross-sections of the U.S. population with unknown exposures (16, 17). NHANES II indicates an overall prevalence of 3.9% for localized pleural changes (plaques) among those aged 35 to 74 years (17). This prevalence almost doubled from the 1971–1975 to the 1976–1980 cohort (17). Within our study, a similar background prevalence at 3.7% was identified within the lowest exposure quartile (⩽0.24 fiber/cc-years) using a conservative analytical approach through inclusion of participants and living nonparticipants, with the latter assumed to have normal chest radiographs. The prevalence increased to 13.9% within the second lowest exposure quartile (range, 0.25–0.74 fiber/cc-years).

Pleural changes are the most common sequelae of asbestos exposure (18–20), most commonly appearing 20 to 30 years after initial exposure (18, 19, 21, 22). Pathologically, localized pleural changes or pleural plaques appear as a “basket weave” pattern of acellular hyalinized collagen involving the parietal pleura (21). Diffuse pleural thickening, which can involve the visceral pleura (23), was demonstrated in 4.3% of participants. This finding was similar to the 6.1% prevalence found in a study of asbestos-exposed sheet-metal workers using the same classification definition as our study (24).

Interstitial changes (irregular opacities) were demonstrated in 2.9% of participants and were significantly related to CFE. These types of changes are typically seen after significant and prolonged occupational asbestos exposures (25–28). Both age and cigarette smoking are potential confounding factors in regard to classification of irregular opacities at the ⩽1/1 profusion category (29). Confounding is unlikely in this study because two participants with profusion scores of 1/1 were never-smokers, six of eight had pleural changes, and all eight were in the higher CFE range. Previous predicted thresholds of CFE for the occurrence of interstitial changes ranged from 25 to 100 asbestos fiber/cc-years (27). The mean CFE (SD) of those with interstitial changes in our study with no reported commercial asbestos exposure was 11.37 (6.82) fiber/cc-years. In an unexposed U.S. population of 1,422 blue-collar employees, Castellan and colleagues demonstrated interstitial changes (profusion ⩾ 1/0) in 0.2% of employees based on a similar methodology using three B readers (14). A meta-analysis of published North American chest radiographic data regarding small opacities in unexposed populations yielded a prevalence of 1.6% (95% CI, 0.6–2.6%) (30).

Potential cofactors examined were age, BMI, sex, and hire date. Older workers usually have longer employment duration, and therefore a higher CFE and longer latency from initial exposure. BMI is a potential cofactor because subpleural fat can mimic pleural thickening (31). This was not the finding in our study because the percentage of distribution of pleural changes was evenly distributed across all BMI categories (Table 4). Because women are more likely to have lower exposure jobs, sex was examined. Finally, hire date was examined due to decreased fiber exposure by 1974 with the implementation of environmental control measures (6). Both hire date and age were significantly associated with increased pleural changes and increased CFE (P < 0.001). After placing all cofactors in the model, there was still a consistent relationship between CFE and pleural changes, both in the overall model and within the exposure quartile model (Figure 2). This relationship persisted after removal of all participants and living nonparticipants with a history of potential past commercial asbestos exposure.

An increased prevalence of chest radiographic changes has been identified in the vermiculite miners and millers of Libby, Montana. McDonald and colleagues calculated the mean CFE of current workers at 40 fiber/cc-years, with a prevalence of interstitial changes and pleural thickening of 9.1 and 15.9%, respectively (32). For past workers, the mean CFE was 119 fiber/cc-years and the prevalence of interstitial changes and pleural thickening was 37.5 and 52.5%, respectively (32). Amandus and colleagues in a similar study estimated the mean CFE at 119 fiber-years, with interstitial changes and pleural thickening in 10 and 13%, respectively (33). These studies indicate that high exposure to Libby amphibole fibers leads to radiographic changes. On the basis of our study, it appears pleural changes can occur at low lifetime cumulative fiber exposure levels as demonstrated by the 12% prevalence within participants and living nonparticipants with less than 1.92 fiber/cc-years CFE, and 20% prevalence within participants with less than 2.21 fiber/cc-years CFE.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry studied 6,668 people who lived in and around Libby for at least 6 months before December 1990, including those ever employed in the vermiculite mining and milling operation (34). The prevalence of pleural changes was 17.8% overall and 51% in miners and millers (34). Interstitial changes were demonstrated in less than 1% of the subjects (34). Progressive losses in lung function also have been reported in 123 Libby residents with and without occupational exposure who had predominantly pleural changes with minimal to no interstitial changes (35).

Mortality studies of Libby miners and millers have shown significant increased mortality due to asbestosis, lung cancer, cancer of the pleura, and mesothelioma (36, 37). Of particular interest in relationship to the results of our study were the findings by Sullivan of a significant excess mortality from nonmalignant respiratory disease in those workers with less than 4.5 fibers/cc-years of cumulative exposure (38). Also, those workers employed for less than 1 year demonstrated a significant increased mortality from both nonmalignant respiratory disease and lung cancer (38).

A potential limitation of this study was participation bias. Although age was similar between participants and nonparticipants, those hired on or before 1973 were more likely (P < 0.01) to participate. Therefore, there could be less confidence in the prevalence of pleural changes by quartile of exposure, especially for the workers with the lowest exposure. Inclusion of all living nonparticipants with the assumption that their radiographs were normal did not change the finding of a significant trend of increasing pleural changes across increasing exposure quartiles. Consequently, participation bias with respect to disease prevalence is likely negligible.

A second limitation is potential misclassification of exposure due to limited industrial hygiene data at the facility on which both the 1980 and the follow-up studies were based (6). Reported extensive overtime by workers was not taken into consideration in dose reconstruction, resulting in potential underestimation of exposure. These factors would have an impact particularly at the lower range of the CFE. There were no exposure data before 1972 and personal monitoring was not implemented until 1976 (6). After 1980, Libby vermiculite was no longer used at the manufacturing facility. Despite these limitations, the demonstration of a nonsignificant trend between pleural changes and increasing exposure quartiles in workers hired after 1973, when there was more comprehensive environmental measurement, is supportive of the finding of pleural changes at low CFE levels. These results are especially relevant given that all the living nonparticipants in the analysis were considered as having normal chest radiographs.

Ores from other mines, reportedly containing no or minimal amphibole fibers, were used until 2001 when vermiculite was removed from all products (38). If, in fact, these ores contained amphibole fibers, this would result in underestimation of exposure. In 2000, an evaluation of the facility by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health found 0.02 fiber/cc for the vermiculite expander operator averaged over 8 hours (39). The combined sample results for all other jobs or general work areas were below detectable concentrations (39).

Another limitation is that this study may underestimate the prevalence of pleural and/or interstitial changes, particularly in the older workers, due to nonparticipation related to either illness or death. This observation is supported by the finding that deceased workers, with a mean age of 74 years, had the highest mean CFE at 3.31 fiber/cc-years. A further limitation is related to potential variability and observer agreement in the reading of chest radiographs. This issue was evaluated for two of the three participating B readers in a related study (40), which demonstrated good intrareader reliability with kappa statistics ranging from 0.47 to 0.68.

While in operation, the Libby mine may have provided as much as 80% of the world's vermiculite supply (4). Much of it was used in attic insulation products like Zonolite (41). An EPA evaluation of vermiculite attic insulation found amphibole fiber exposures ranging from 0.0133 to 0.4053 fiber/cc during 30 minutes of various home repair or remodeling activities that disturb the insulation (42). If these data are extrapolated to an 8-hour TWA, this average can result in airborne exposures exceeding the Occupational Safety and Health Administration permissible exposure level of 0.1 fiber/cc for regulated asbestos (42). Given the widespread use of vermiculite attic insulation, this finding has prompted federal health warnings (43, 44). The results of our study are supportive of the EPA precautionary recommendations. The investigative team involved with this study in concert with investigators from region 8 of the EPA are pursuing additional potential exposure information to validate and refine the CFE matrix used in this cohort investigation.

Conclusions

These results indicate that exposures to winchite, richterite, and tremolite amphibole fibers among users of Libby vermiculite ore within an industrial process cause pleural thickening at low lifetime CFE levels of less than 2.21 fiber/cc-years. This is below the lifetime CFE for a worker exposed to the current Occupational Safety and Health Administration permissible exposure level standard of 0.1 fiber/cc for regulated asbestos in general industry over a 45-year working life (4.5 fiber/cc-years) (45). In Libby miners and millers, there has been an increase in nonmalignant and malignant respiratory mortality as well as in mesothelioma associated with exposure to these amphibole fibers. Together, these findings raise public health concerns, in view of the extensive distribution and use of Libby vermiculite in commercial and residential applications throughout the United States and elsewhere.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the men and women who were participants in this study and their families who provided information. They also appreciate the cooperation of the company personnel, and they acknowledge and thank Aubrey Miller, M.D., M.P.H., from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, for his technical assistance.

Supported by funds from the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act trust fund through a cooperative agreement with the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ATSDR grant U50/ATU573006s. In addition, this study was partially supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grant ES10957. The ATSDR reviewed and approved this report before submission.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200706-841OC on December 6, 2007

Conflict of Interest Statement: A.M.R. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. J.E.L. serves as fact and state-of-the-art witness for the U.S. Department of Justice for the District of Montana, Missoula Division, in the United States of America vs. W.R. Grace, et al. K.K.D. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. R.S. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. H.F. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. T.H. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. E.B. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. J.W. does “B” readings for both plaintiff and defense attorneys in relationship to asbestos exposure. C.M. renders B-readings for both plaintiff and defense attorneys in relationship to asbestos exposure. R.T.S. performs B readings for both plaintiff and defense attorneys in relationship to asbestos exposure. R.T.S. also provides B readings for commercial (e.g., Health Network of America) and noncommercial (e.g., State of Ohio Bureau of Workers Compensation) entities. G.K.L. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. V.K. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript

References

- 1.Lockey JE. Nonasbestos fibrous minerals. Clin Chest Med 1981;2:203–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amandus HE, Wheeler R, Jankovic J, Tucker J. The morbidity and mortality of vermiculite miners and millers exposed to tremolite-actinolite: part I. Exposure estimates. Am J Ind Med 1987;11:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. National Asbestos Exposure Review (NAER) [Internet] [accessed 2008. Jan 18]. Available from: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/asbestos/sites/national_map

- 4.California Environmental Health Investigations Branch. Vermiculite Health Statistics Review: public health activities [Internet] [accessed June 20, 2006]. Available from: http://www.ehib.org/cma/project.jsp?project_key=VERM01

- 5.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Health assessment document for vermiculite. Washington (DC): U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; September 1991. Publication No. EPA/600/8-91/037.

- 6.Lockey JE, Brooks SM, Jarabek AM, Khoury PR, McKay RT, Carson A, Morrison JA, Wiot JF, Spitz HB. Pulmonary changes after exposure to vermiculite contaminated with fibrous tremolite. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984;129:952–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rohs AM, Dunning K, Lockey JE, Hilbert T, Shipley R, Meyer C, Wiot J, Shukla R. University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH. Pleural plaques in workers exposed to asbestiform contaminated vermiculite ore: a twenty year follow-up [abstract]. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2005;2:A816. [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Labour Office. Guidelines for the use of the ILO international classification of radiographs of pneumoconioses, revised 2000. ed. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office; 2002.

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Toxic Substances and Diseases. Health consultation: the Scotts Company, LLC. EPA Facility ID: OHD990834483. September 22, 2005.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight and obesity: defining overweight and obesity [Internet] [accessed June 20, 2006]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/obesity/defining.htm

- 11.Atkinson GR, Rose D, Thomas K, Jones D, Chatfield EJ, Going JE. Collection, analysis and characterization of vermiculite samples for fiber content and asbestos contamination. Kansas City, MO: Midwest Research Institute EPA Office of Pesticides and Toxic Substances; 1982. Publication No. EPA 68-01-5915.

- 12.Moatamed F, Lockey JE, Parry WT. Fiber contamination of vermiculites: a potential occupational and environmental health hazard. Environ Res 1986;41:207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meeker GP, Bern AM, Brownfield IK, Lowers HA, Sutley SJ, Hoefen TM, Vance JS. The composition and morphology of amphiboles from the Rainy Creek complex, near Libby, Montana. Am Mineral 2003;88:1955–1969. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castellan RM, Sanderson WT, Petersen MR. Prevalence of radiographic appearance of pneumoconiosis in an unexposed blue collar population. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985;131:684–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson HA, Lilis R, Daum SM, Selikoff IJ. Asbestosis among household contacts of asbestos factory workers. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1979;330:387–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogan WJ, Gladen BC, Ragan NB, Anderson HA. US prevalence of occupational pleural thickening: a look at chest X-rays from the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol 1987;126:893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogan WJ, Ragan NB, Dinse GE. X-ray evidence of increased asbestos exposure in the US population from NHANES I and NHANES II, 1973–1978. National Health Examination Survey. Cancer Causes Control 2000;11:441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levin SM, Kann PE, Lax MB. Medical examination for asbestos-related disease. Am J Ind Med 2000;37:6–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillerdal G. Pleural plaques: incidence and epidemiology, exposed workers and the general population: a review. Indoor Built Environ 1997;6:86–95. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz DA. The clinical relevance of asbestos-induced pleural fibrosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1991;643:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Thoracic Society. Medical section of the American Lung Association: diagnosis and initial management of nonmalignant diseases related to asbestos. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:691–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenstock L, Hudson LD. The pleural manifestations of asbestos exposure. Occup Med 1987;2:383–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomon A. Radiologic features of asbestos-related visceral pleural changes. Am J Ind Med 1991;19:339–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz DA. New developments in asbestos-induced pleural disease. Chest 1991;99:191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lilis R, Daum S, Anderson H, Sirota M, Andrews G, Selikoff IJ. Asbestos disease in maintenance workers of the chemical industry. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1979;330:127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irwig LM, du Toit RS, Sluis-Cremer GK, Solomon A, Thomas RG, Hamel PPH, Webster I, Hastie T. Risk of asbestosis in crocidolite and amosite mines in South Africa. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1979;330:35–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sporn TA, Roggli VL. Asbestosis. In: Roggli VL, Oury TD, Sporn TA, editors. Pathology of asbestos-associated diseases, 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2004. pp. 71–103.

- 28.Churg A, Wright JL, Vedal S. Fiber burden and patterns of asbestos-related disease in chrysotile miners and millers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;148:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dick JA, Keith W, Morgan C, Muir DFC, Reger RB, Sargent N. The significance of irregular opacities on the chest roentgenogram. Chest 1992;101:252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer JD, Islam SS, Ducatman AM, McCunney RJ. Prevalence of small lung opacities in populations unexposed to dusts: a literature analysis. Chest 1997;111:404–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee YC, Runnion CK, Pang SC, de Klerk NH, Musk AW. Increased body mass index is related to apparent circumscribed pleural thickening on plain chest radiographs. Am J Ind Med 2001;39:112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald JC, Sebastien P, Armstrong B. Radiological survey of past and present vermiculite miners exposed to tremolite. Br J Ind Med 1986;43:445–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amandus HE, Althouse R, Morgan WK, Sargent EN, Jones R. The morbidity and mortality of vermiculite miners and millers exposed to tremolite-actinolite: part III. Radiographic findings. Am J Ind Med 1987;11:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peipins LA, Lewin M, Campolucci S, Lybarger JA, Miller A, Middleton D, Weis C, Spence M, Black B, Kapil V. Radiographic abnormalities and exposure to asbestos-contaminated vermiculite in the community of Libby, Montana, USA. Environ Health Perspect 2003;111:1753–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitehouse AC. Asbestos-related pleural disease due to tremolite associated with progressive loss of lung function: serial observations in 123 miners, family members, and residents of Libby, Montana. Am J Ind Med 2004;46:219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amandus HE, Wheeler R. The morbidity and mortality of vermiculite miners and millers exposed to tremolite-actinolite: part II. Mortality. Am J Ind Med 1987;11:15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald JC, Harris J, Armstrong B. Mortality in a cohort of vermiculite miners exposed to fibrous amphibole in Libby, Montana. Occup Environ Med 2004;61:363–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan PA. Vermiculite, respiratory disease, and asbestos exposure in Libby, Montana: update of a cohort mortality study. Environ Health Perspect 2007;115:579–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. NIOSH site visit report 2002-0437: the Scotts Company, Marysville, OH. Morgantown, WV: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 2004. Publication No. NIOSH 2002-0437.

- 40.Lawson CC, LeMasters MK, LeMasters GK, Reutman SS, Rice CH, Lockey JE. Reliability and validity of chest radiograph surveillance programs. Chest 2001;120:64–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Vermiculite consumer products [Internet] [accessed June 20, 2006]. Available from: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/news/vermiculite051603.html

- 42.Versar, Inc.; Environmental Protection Agency. EPA's pilot study to estimate asbestos exposure from vermiculite attic insulation: research conducted in 2001. and 2002. Washington, DC: Environmental Protection Agency's Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics; 2003. Publication No. EPA PB2003-105838.

- 43.Environmental Protection Agency; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Current and best practices for vermiculite attic insulation. Washington, DC: Environmental Protection Agency; 2003. Publication No. EPA 747-F-03-001.

- 44.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Fact sheet: NIOSH recommendations for limiting potential exposures of workers to asbestos associated with vermiculite from Libby, Montana. 2003. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2003-141 [Internet] [accessed 2007 Apr 4]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/NIOSH/docs/2003-141.

- 45.U.S. Department of Labor, Occupation Safety and Health Administration. [Internet] [accessed 2007. Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=9995