Abstract

Rationale: The pathogenesis of primary graft dysfunction (PGD), a serious complication of lung transplantation, is poorly understood. Human studies and rodent models have shown that collagen type V (col[V]), stimulates IL-17–dependent cellular immunity after lung transplantation.

Objectives: To determine whether patients with end-stage lung disease develop pretransplant col(V)-specific cellular immunity, and if so, the impact of this response on PGD.

Methods: Trans-vivo delayed-type hypersensitivity (TV-DTH) assays were used to evaluate memory T-cell responses to col(V) in 55 patients awaiting lung transplantation. PaO2/FiO2 index data were used to assess PGD. Univariate risk factor analysis was performed to identify variables associated with PGD. Rats immunized with col(V) or irrelevant antigen underwent lung isografting to determine if prior anti-col(V) immunity triggers PGD in the absence of alloreactivity.

Measurements and Main Results: We found that 58.8% (10/17) of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and 15.8% (6/38) of patients without idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis tested while on the wait list for a lung transplant were col(V) DTH positive. Col(V) reactivity was CD4+ T-cell and monocyte mediated, and dependent on IL-17, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. PaO2/FiO2 indices were impaired significantly 6–72 hours after transplantation in col(V)-reactive versus nonreactive patients. Univariate risk factor analysis identified only preoperative TV-DTH to col(V) and ischemic time as predictors of PGD. Finally, in a rat lung isograft model, col(V) sensitization resulted in significantly lower PaO2/FiO2, increased local TNF-α and IL-1β production, and a moderate-to-severe bronchiolitis/vasculitis when compared with control isografts.

Conclusions: The data suggest that activation of innate immunity by col(V)-specific Th-17 memory cells represents a novel pathway to PGD after lung transplantation.

Keywords: lung transplantation, primary graft dysfunction, collagen type V, autoimmunity, memory T cell

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Primary graft dysfunction continues to be a major barrier to successful transplantation. Despite optimal patient selection and ideal procurement techniques, primary graft dysfunction affects 11–25% of patients.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Activation of innate immunity by col(V)-specific Th-17 memory cells represents a novel pathway to primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation.

The historic paradigm of allograft failure due primarily to humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to foreign major histocompatability complex (MHC) antigens has recently been challenged by additional hypotheses (1–3). Although it is clear that immunity to donor human leukocyte antigen (HLA) serves a significant role in mediating allograft rejection, recent evidence suggests that self-antigens exposed during ischemia–reperfusion injury may, under some circumstances, present an equal, if not greater, barrier to graft acceptance (4–6). In lung transplantation, one such cryptic self-antigen is collagen type-V (col[V]) (2). Col(V) is classified as a minor fibrillar collagen and, in the human lung, the ratio of matrix collagens is 86:28:8:1.6 (for collagens I, III, IV, and V, respectively) (7). Under normal physiologic conditions, col(V) coassembles into heterotypic fibrils with the major fibrillar collagen type I (8, 9). In fact, the majority of the col(V) monomer is normally partitioned to the interior of col(V)/col(I) heterotypic fibrils, so that disruption of such fibrils with acid, metalloproteases, or low temperature is needed to unmask col(V) epitopes for its immunohistochemical detection (8, 9).

Immunohistochemistry analysis indicates that col(V) becomes exposed in the lung matrix after ischemia–reperfusion injury in rat lung isografts and allografts (10), and that col(V) peptides are released in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (11). The fact that CD4+ T-cell clones specific for col(V) can be derived from rejecting rat lung allografts (11) suggests that induction of col(V)-specific T cells is a normal byproduct of alloimmune activation in the ischemically injured lung. Exposure of col(V) to the host immune system under normal circumstances may be benign, because rat lung isografts are routinely accepted without evidence of acute or chronic rejection (11). However, significant isograft infiltration and an acute rejection-like pathology occurs if syngeneic lymph node cells are transferred from rats primed with col(V) at the time of lung isograft (10, 11). A key element in this rapid autoimmune pathogenesis is the induction of IL-17, a potent proinflammatory cytokine (10). IL-17 is a cytokine produced by a subset of memory CD4+ T cells (Th-17), which have been implicated in a variety of autoimmune diseases (12); however, relatively little is known about these memory T cells, their specific autoantigen targets, and their unique developmental pathways/mechanisms of pathogenesis in humans (13).

We recently reported the development of a col(V)-specific IL-17 and monokine-dependent cellular immune response after lung transplantation in a subset of patients on standard immunosuppressive therapy. Importantly, the appearance of this response in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was strongly correlated with subsequent onset of severe bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) (14); however, pretransplant col(V) cellular immunity status was not evaluated. Whether any single end-stage lung disease is associated with IL-17–dependent autoimmunity to col(V) is currently unknown, nor is the potential impact that such autoimmune T-memory cells may have on transplant outcomes. Using the trans-vivo delayed-type hypersensitivity (TV-DTH) test as a clinical screening assay (15–17), and a rat model of orthotopic lung transplantation, we tested the hypothesis that (1) certain end-stage lung diseases predispose to col(V)-specific autoimmunity and (2) that preexisting anti-col(V) autoimmunity triggers primary graft dysfunction (PGD) in the transplanted lung.

METHODS

TV-DTH Assay

The TV-DTH assay was used to detect antigen-specific memory responses (16, 18, 20). Patients awaiting lung transplant (n = 55) and eight healthy individuals donated blood for measurement of TV-DTH responses. Briefly, 7–9 × 106 mononuclear cells derived from either PBMCs or hilar lymph node (obtained at the time of transplant surgery) were injected, together with antigen, into the footpads of CB.17 SCID (severe combined immunodeficient) mice. Animals were housed and treated in accordance with Association for Assessment of Laboratory Animal Care (AALAC) and National Institutes of Health guidelines. Swelling was measured after 24 hours using a dial thickness gauge, and postinjection measurements were compared with preinjection measurements to determine specific swelling response. TV-DTH reactivity was evidenced by the change in footpad thickness, using units of 10−4 inches relative to background swelling due to injection of mononuclear cells and phosphate-buffered saline alone. This value was subtracted from the swelling responses measured for each individual test antigen to obtain a net swelling value. Typical recall TV-DTH responses to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or tetanus toxoid (TT) in seropositive individuals are between 25 × 10−4 and 60 × 10−4 inches of net swelling. Net swelling responses of 25 × 10−4 inches or more were therefore considered positive. Responses below 25 × 10−4 inches were considered negative.

In some (TV-DTH) experiments, immunomagnetic beads (MACs Beads; Miltenyi Biotrec, Auburn, CA) were used to deplete CD4+, CD8+, or CD14+ cells from PBMCs before TV-DTH. In other assays, cytokines were neutralized with a 5-μg coinjection of antibodies to human IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (both from BD Biosciences), IL-1β (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA), or IL-17 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). These antibodies did not cross-react with mouse cytokines.

Antigens and Immunizations

Inactivated EBV (Viral Antigens, Inc., Gaithersburg, TN) was used as a positive control recall antigen. Human col(V) (α1[1]/α2[2]) was purified from placenta as described (21) and used in both TV-DTH monitoring and rat immunization experiments. Native, nondenatured, bovine col(II) was purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). Collagens were tested in TV-DTH at 5 μg per injection. Hen egg lysozyme (HEL) was purchased from Sigma. Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats were immunized at the base of the tail with 200 μg of human col(V) or HEL (control) emulsified in 200 μl of complete Freund's adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI).

Human Subjects Design

The Human Subjects Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin at Madison approved all aspects of this study protocol before any patient enrollment, data collection, or data analysis. Fifty-five patients underwent pretransplant analysis for TV-DTH reactivity to col(V) starting in May of 1999. PBMC samples were collected and analyzed at the time of listing for transplant and during routine follow-up visits over the course of their time on the waiting list. Because of the uncertainty of whether, or when, a patient would receive a lung transplant, the interval between last PBMC TV-DTH and time of transplantation could not be standardized. Therefore, in a subset of patients, recipient hilar lymph nodes from the ipsilateral side of the transplant were harvested and processed to provide a uniform, time zero, measure of collagen reactivity. In addition, this allowed us to compare memory T-cell responses in peripheral blood with the central thoracic lymph node compartment. During the study period, 33 of 55 patients received a lung transplant.

All patients underwent arterial blood sampling at time zero and then again at 6, 12, 24, and 72 hours post-transplant, and as clinically indicated, as part of standard monitoring and a standardized ventilator weaning protocol. For the purpose of this study, time point zero is defined as the final blood gas sample before leaving the operating theater. For those transplantations requiring the use of cardiopulmonary bypass, the final blood gas sample after weaning off bypass completely is considered time zero. The PaO2/FiO2 index was then calculated at each time point for routinely ventilated patients or the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support was documented.

Animal Study Design

Pathogen-free male WKY (RT1l) rats were used for the study (250–300 g at the time of transplantation). All rats were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) and housed in the Laboratory Animal Resource Center at the Indiana University School of Medicine (Indianapolis, IN) in accordance with institutional guidelines. All studies were approved by the Laboratory Animal Resource Center at the Indiana University School of Medicine.

Orthotopic transplantation of naive left lung isografts into WKY rats immunized with either col(V) or HEL (control) was performed as previously reported (11, 20, 21). Survival exceeded 90% in all transplantation groups. No immunosuppressive therapy was given at any time during the experimental period. Animals were maintained for 72 hours post-transplantation. At that time point, they were then anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of ketamine and xylazine, intubated through a tracheostomy, and cannulated via the left carotid artery. The rats were mechanically ventilated with a rodent ventilator (model 683; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) with 100% oxygen and isoflurane at a minute ventilation to keep the PaCO2 level at 40 mm Hg. Arterial blood samples were run on an IRMA SL blood analysis system (Diametrics Medical, Roseville, MN). After arterial samples were obtained, BAL was performed on native and transplanted lungs before harvesting, fixing, sectioning, and staining as previously reported (10). Sections were then examined by standard light microscopy for cellular infiltration.

Statistical Analysis

TV-DTH responses to col(V) and collagen type II in healthy normal control subjects and in patients on the waitlist for a lung transplant were compared by a Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test. Statistical analysis of PaO2/FiO2 index (P/F ratio) was conducted using a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. Because the need for ECMO support resulted in inability to calculate PaO2/FiO2 indices, an imputed surrogate (≤50) was used to recover these patients for inclusion in analysis. Last-observation-carried-forward imputation was used to repopulate any missing index measurements during the 72-hour study period. Least squares means were calculated for each subgroup at all time points. Index data are presented as the least squares mean ± SE. Time point comparisons were done using a two-sided repeated-measures ANOVA for inequality. Statistical analysis of PaO2/FiO2 index at 72 hours post-transplant in the rat model was conducted using a two-sided Welch test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significantly different for all analyses. All statistical analyses were obtained in SAS version 9.1 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

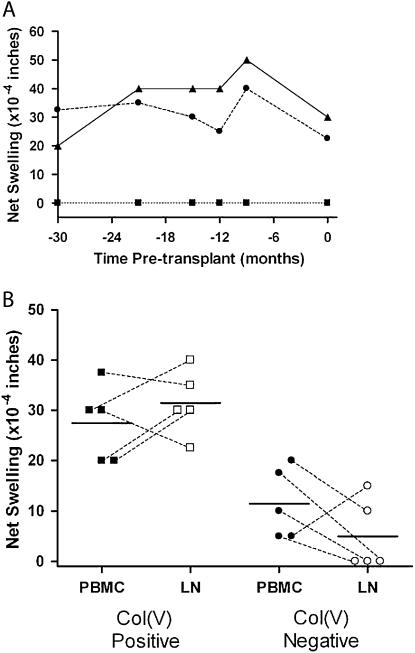

To determine if memory T cells specific for col(V) were present in persons with end-stage pulmonary disease, 55 patients awaiting lung transplantation were tested for reactivity to col(V) using the TV-DTH assay during the period of May 1999 to September 2006. Subsequently, 33 persons tested before transplantation underwent lung transplantation, 28 of whom underwent transplantation after 2004. The median time from last TV-DTH assay to transplantation was 0.9 weeks (range, 0–48.9 wk). Demographic data from the study patients are shown in Table 1. The disproportionately high number of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) tested reflects both the impact of the lung allocation scoring (LAS) system and an active initiative to recruit these patients for further study at our institution. Figure 1A shows TV-DTH results from a single patient sampled at six separate time points, ranging from 30 months before transplant up to the day of transplantation. Consistently strong recall responses to EBV were demonstrated with a nearly equivalent response to col(V) in this 64-year-old patient with IPF at all time points. Collagen type II never stimulated a swelling response during this time course. Data from this patient are representative of the TV-DTH–positive transplanted study cohort as a whole, with a group median number of DTH determinations of three and group mean time of follow-up of 31.1 weeks. Figure 1B shows the TV-DTH responses of 10 patients sampled both centrally (hilar lymph nodes taken at the time of transplantation, Day 0) and peripherally (PBMCs sampled within 1 wk before transplant). As is evident by the scatterplot, the TV-DTH reactivity was not significantly different between the central and peripheral compartments (col[V] positive [P = 0.3], col[V] negative [P = 0.3] Wilcoxon matched pairs test). As a whole, lymph node–derived mononuclear cell preparations resulted in stronger mean responses to col(V) in the TV-DTH–positive group, negative responses to col(V) in the TV-DTH–negative group, and lower overall background swelling in both groups. Patents could therefore readily be segregated into TV-DTH–positive and TV-DTH–negative groups on the basis of average reactivity to col(V) of less than 25 × 10−4 or greater than 25 × 10−4 inches or more based on PBMC and hilar lymph node results.

TABLE 1.

PATIENT DEMOGRAPHICS AND DISEASE SUBTYPES

| Category | DTH Patients |

|---|---|

| Patients, total n | 55 |

| α1-Antitrypsin, n | 4 |

| COPD, n | 16 |

| Cystic fibrosis, n | 9 |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, n | 17 |

| Other, n | 9 |

| Number transplanted | 33 |

| Bilateral, n (%) | 13 (37%) |

| Single, n (%) | 20 (63%) |

| Male recipient, n (%) | 14 (40%) |

| Mean recipient age, yr | 50 ± 12.1‡ |

| HLA matching (⩾1 allele), % | |

| HLA-A | 57.6 |

| HLA-B | 30.3 |

| HLA-DR | 42.4 |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DTH = delayed-type hypersensitivity.

Mean ± SD.

Demographic and HLA matching data for all trans-vivo DTH–tested (n = 55) and subsequently transplanted (n = 33) patients during the study interval of May 1999 to September 2006. The “other” diagnostic category includes primary pulmonary hypertension (n = 4), ciliary dyskinesia (n = 2), sarcoidosis (n = 1), graft versus host disease from bone marrow transplantation (n = 1), and idiopathic bronchiectasis (n = 1). HLA matching data are presented as the percentage of patients with at least one allele match between donor and recipient.

Figure 1.

Consistency and correlation between peripheral and intrathoracic-derived mononuclear cells for collagen V (col[V]) trans-vivo delayed-type hypersensitivity (TV-DTH). (A) Mean recall response from Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) over all time points was 37. 5 × 10−4 inches, with overall col(V) responses ranging from 22.5 to 40 × 10−4 inches of net swelling. Mean col(V) swelling response over all time points was 30 × 10−4 inches. Collagen type II (col[II]) did not elicit a TV-DTH swelling response. Triangles, EBV; circles, col(V); squares, col(II) (B) Differences in TV-DTH response from peripheral and hilar lymph node–derived mononuclear cells (PBMC and LN) are presented in five col(V) responders and five col(V) nonresponders. Dotted lines denote paired observations for each patient and solid lines represent group means. There were three patients with borderline responses (20 × 10−4 inches) who could not be characterized based on PBMC samples alone, but with LN sampling clearly demarcated their respective TV-DTH status. Closed circles and squares, PBMC; open circles and squares, LN.

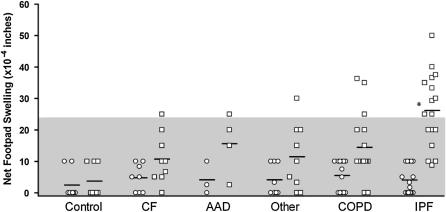

Next, we wished to determine if pretransplant reactivity was a function of primary diagnosis leading to end-stage lung disease. Pretransplantation reactivity to both collagen type II and V is shown in Figure 2 among all 55 persons with end-stage lung disease awaiting transplantation and 8 healthy control subjects. Col(II) was chosen as a control because it is expressed in cartilage, but not the lung. Sixteen persons demonstrated positive response to col(V). Overall, there was no significant reactivity to col(II) in any of the subgroups or control subjects. To our surprise, reactivity to col(V) was significantly elevated in the IPF subgroup as a whole (P value, 0.0003). Reactivity to col(V), however, was not restricted to the diagnosis of IPF, because six persons with other diagnoses (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], n = 3; cystic fibrosis, n = 1; α1-antitrypsin disease [AAD], n = 1; other [ciliary dyskinesia], n = 1) were also strongly reactive. Overall, patients with IPF showed the highest proportion of patients reaching the threshold of significant reactivity to col(V) (10/17, 58.8%), followed by AAD (1/4, 25%), COPD (3/16, 18.8%), cystic fibrosis (1/9, 11.1%), and other (1/9, 11.1%). No patients demonstrated a T-memory response to collagen type II, and no persons crossed from col(V) reactive to col(V) nonreactive or vice versa before transplant. Responses to the positive control/recall antigen (EBV) were similar (30–35 × 10−4 in) among patients of differing end-stage lung disease. All patients reacted strongly to EBV, demonstrating the ability of each patient to mount an intact memory response against common recall antigens, thus eliminating relative immunosuppression or anergy as a potential mechanism in those patients who failed to demonstrate a memory response to col(V).

Figure 2.

Evidence for differences in pretransplant collagen V (col[V]) trans-vivo delayed-type hypersensitivity (TV-DTH) status by lung disease group. Pretransplant TV-DTH responses to collagen II (col[II]) (circles) or col(V) (squares) in 55 patients with end-stage lung disease and 8 healthy control subjects. The diagnostic category “other” includes those patients defined in Table 1. Responses were averaged from duplicate determinations for each patient including peripheral blood leukocyte and lymph node preparations. Shaded area represents negative TV-DTH values (<25 × 10−4 inches). AAD = α1-antitrypsin disease; CF = cystic fibrosis; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

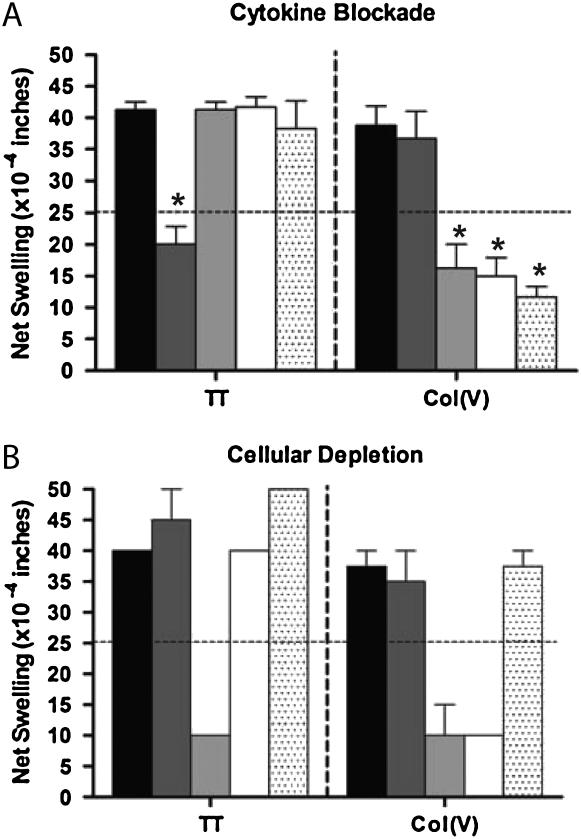

To better characterize the cytokines and cell populations involved in the cell-mediated immune response to col(V), we undertook a series of cell depletion and cytokine blockade experiments. Figure 3A shows the results of antibody blocking experiments. TV-DTH response to col(V) was significantly inhibited (P < 0.05) by blocking antibodies to TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17. Anti–IFN-γ antibody did not significantly impact the swelling response (P = not significant). This is in contrast to memory responses to TT, which were significantly inhibited by antibody to human IFN-γ (P < 0.05), but were resistant to TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17 blockade (P = not significant). Furthermore, cell depletion assays indicated that both a CD4 T cell and a monocyte (CD14+) were required for the col(V) immune response (Figure 3B). In contrast, the TT recall response was CD4 dependent, but monocyte independent. Depletion of CD8+ did not significantly alter either response.

Figure 3.

Cytokine and cellular requirements of the trans-vivo delayed-type hypersensitivity (TV-DTH) response to collagen V (col[V]). (A) Cytokine neutralization was conducted by coinjection of blocking antibodies at the time of TV-DTH injection. Isotype control injections had no effect on tetanus toxoid (TT) recall or col(V) TV-DTH responses. Classic TT recall swelling responses were blocked by IFN-γ (P = 0.008); however, this antibody had no effect on col(V) swelling responses. Blockade of either IL-17 (P = 0.004), IL-1β (P = 0.003), or tumor necrosis factor-α (P = 0.001) completely abrogated swelling responses to col(V), but not recall antigen. Solid bars, IgG, control; dark shaded bars, IFN-γ; light shaded bars, α-IL-17; open bars, IL-1β; dotted bars, TNF-α. (B) Cellular depletion studies were performed in response to TT recall antigen and col(V). TT responses were abolished by depletion of CD4+ cells, but were not affected by depletion of CD14+ or CD8+ cells. Col(V) responses were equally abrogated by depletion of either CD4+ or CD14+ cells. Solid bars, peripheral blood leukocytes; dark shaded bars, CD8 depleted; light shaded bars, CD4 depleted; open bars, CD14 depleted; dotted bars, sham depleted.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that the TV-DTH assay for reactivity to col(V) is sensitive, specific, and reproducible over time, with correlation between central and peripheral pools of memory T cells. Furthermore, like the col(V)-specific cellular immunity that develops after lung transplantation under conditions of immunosuppressive drug therapy (14), pretransplant reactivity requires both CD4+ memory T cells and monocytes, IL-17, and monokines, suggesting a Th-17, rather than a Th-1 pathway for col(V)-specific autoimmunity.

Given that pretransplant responses to col(V) were present in a subset of patients, we questioned the impact that this reactivity would portend on early graft function. Of the 55 patients tested for col(V) TV-DTH while on the waiting list, 33 received a lung transplant during this study. Before computing outcomes in the col(V) TV-DTH–negative and TV-DTH–positive patients, we attempted to characterize other pretransplant risk factors and functional status in these two groups. Table 2 provides a summary of these data. There was no significant difference between the groups with regard to recipient age, ischemic time, pretransplant panel of reactive antibodies (PRA), or HLA–A/B/DR matching. Functionally, the TV-DTH–reactive group required less oxygen and was able to walk farther on six-minute-walk evaluation, although this was not statistically significant. The last functional assessment was completed at a similar median time point before transplantation in the col(V)-reactive and nonreactive groups (9.1 vs. 11.9 wk, respectively).

TABLE 2.

DELAYED-TYPE HYPERSENSITIVITY SUBGROUP COMPARISON OF TRANSPLANTED PATIENTS*

| Category | Negative-DTH Patients (n = 24) | Positive-DTH Patients (n = 9) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic time, min† | 417.0 ± 7.1 | 414.9 ± 13.9 | 0.97 |

| Mean PRA (historic maximum), % | 0.11 | 0.40 | 0.25 |

| HLA matching (A, B, DR) † | 1.38 ± 0.25 | 1.78 ± 0.36 | 0.43 |

| Mean recipient age, yr | 49.0 | 54.5 | 0.22 |

| Six-minute walk | |||

| Distance walked, ft† | 826 ± 83 | 950 ± 88 | 0.51 |

| Mean oxygen requirement, L/min | 5 | 3 | 0.10 |

| Mean final saturation, SpO2% | 91 | 89 | 0.15 |

Definition of abbreviations: DTH = delayed-type hypersensitivity; PRA = panel reactive antibodies.

Pretransplant risk factor comparison in trans-vivo DTH–tested subgroups.

Mean ± SE.

There were no significant differences between the col(V) TV-DTH positive and negative groups with regard to lung ischemic time, PRA, HLA matching, recipient age, and six-minute-walk functional data.

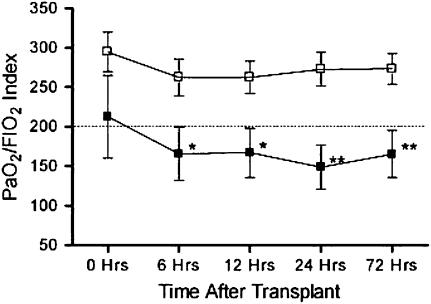

The overall incidence of PGD was 30% (10/33) in this study, as defined by P/F ratio of less than 200 at 72 hours post-transplantation. In the col(V) TV-DTH–reactive patients, the prevalence of PGD was 55% (5/9), compared with 21% (5/24) in the TV-DTH–nonreactive patients. Individual parameters for each patient are shown in Table 3. Five patients required ECMO support, including three with positive TV-DTH reactivity to col(V). As a group, the pretransplant col(V) TV-DTH–reactive group had poorer early allograft function as measured by the PaO2/FiO2 index when compared with col(V)-nonreactive patients (Figure 4). This disparity was not significant at time zero (exit from the operating theater), but became more pronounced by 6 hours post-transplant (P < 0.05) and became most significant at 24 and 72 hours post-transplant (P < 0.01).

TABLE 3.

PaO2/FiO2 INDEX AS A FUNCTION OF DELAYED-TYPE HYPERSENSITIVITY RESPONSE, DISEASE, TIME, AND TRANSPLANT TYPE

| Patient No. | Disease Type | OLT Type | PRA Average, Max (%) | Ischemic Time (min) | DTH Response* | 0 h | 6 h | 12 h | 24 h | 72 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTH-negative group | ||||||||||

| 1 | AAD | BLT | 0 | 342 | 5 | 349.0 | 460.0 | 327.5 | 451.5 | 451.5 |

| 2 | AAD | SLT | 0 | —† | 20 | 429.0 | 185.0 | 221.2 | 366.7 | 275.0 |

| 3 | CF | BLT | 0 | 645 | 0 | 302.0 | 97.0 | 173.0 | 206.0 | 300.0 |

| 4 | CF | BLT | 0 | 342 | 5 | 312.0 | 411.1 | 360.0 | 355.0 | 355.0 |

| 5 | CF | BLT | 0 | 509 | 10 | 214.0 | 166.3 | 163.3 | 256.0 | 377.5 |

| 6 | CF | BLT | 0 | 470 | 10 | 358.0 | 270.0 | 300.0 | 254.0 | 180.0 |

| 7 | CF | BLT | 0 | 560 | 15 | 151.4 | 355.0 | 322.0 | 335.0 | 335.0 |

| 8 | COPD | SLT | 2, 5 | —† | 0 | 432.0 | 240.0 | 242.4 | 366.7 | 366.7 |

| 9 | COPD | SLT | 0 | 310 | 10 | 373.0 | 448.3 | 432.5 | 367.5 | 330.0 |

| 10 | COPD | SLT | 0 | 457 | 10 | 234.0 | 163.3 | 190.0 | 262.5 | 262.5 |

| 11 | COPD | BLT | 0 | 573 | 10 | 348.8 | 338.2 | 292.5 | 262.5 | 262.5 |

| 12 | COPD | SLT | 0 | 320 | 10 | 394.3 | 308.8 | 208.0 | 128.0 | 217.5 |

| 13 | COPD | SLT | 0 | 185 | 10 | 433.0 | 257.6 | 256.0 | 294.0 | 283.3 |

| 14 | COPD | SLT | 0 | 481 | 10 | 362.0 | 335.0 | 257.5 | 327.5 | 337.0 |

| 15 | COPD | SLT | 0 | 350 | 15 | 262.1 | 182.0 | 450.0 | 395.0 | 277.8 |

| 16 | COPD | SLT | 0 | 333 | 20 | 436.0 | 413.3 | 362.5 | 362.5 | 362.5 |

| 17 | IPF | SLT | 0 | 330 | 10 | 131.0 | 317.5 | 350.0 | 242.5 | 297.2 |

| 18 | IPF | SLT | 0 | 371 | 15 | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ |

| 19 | IPF | SLT | 1, 3 | 404 | 20 | 85.0 | 295.0 | 254.0 | 267.5 | 272.2 |

| 20 | IPF | SLT | 0 | 401 | 20 | 244.4 | 278.0 | 360.0 | 328.0 | 288.0 |

| 21 | Other | SLT | 0 | —† | 0 | 415.0 | 232.5 | 226.0 | 257.5 | 195.0 |

| 22 | Other | BLT | 0 | 292 | 5 | 97.9 | 206.3 | 271.4 | 248.0 | 182.5 |

| 23 | Other | BLT | 0 | 353 | 5 | 239.0 | 239.0 | 181.3 | 116.3 | 250.0 |

| 24 | Other | BLT | 0 | 685 | 15 | 419.0 | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ |

| Mean ± SEM | 414.9 ± 13.9 | 10.4 ± 0.3 | 294.7 ± 27.0 | 262.5 ± 22.7 | 262.5 ± 20.3 | 272.9 ± 20.3 | 273.3 ± 19.0 | |||

| DTH-positive group | ||||||||||

| 25 | AAD | SLT | 2, 5 | 297 | 25 | 156.0 | 143.3 | 85.0 | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ |

| 26 | CF | BLT | 2, 3 | 635 | 25 | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ |

| 27 | COPD | SLT | 0 | 684 | 35 | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ | ⩽50‡ |

| 28 | IPF | SLT | 0 | 309 | 25 | 433.0 | 355.0 | 292.5 | 251.5 | 251.5 |

| 29 | IPF | SLT | 0 | 372 | 25 | 249.0 | 271.7 | 257.5 | 257.5 | 257.5 |

| 30 | IPF | SLT | 0 | 336 | 30 | 417.3 | 121.9 | 198.8 | 186.7 | 212.5 |

| 31 | IPF | BLT | 0 | 477 | 35 | 73.0 | 97.0 | 120.0 | 161.7 | 238.0 |

| 32 | IPF | BLT | 0 | 345 | 35 | 363.0 | 215.0 | 193.3 | 198.0 | 186.7 |

| 33 | IPF | SLT | 0 | 298 | 40 | 122.0 | 187.5 | 255.7 | 134.0 | 192.0 |

| Mean ± SEM | 417.0 ± 7.1 | 30.6 ± 0.6 | 212.6 ± 44.1 | 165.7 ± 37.0 | 167.0 ± 33.2 | 148.8 ± 33.1 | 165.4 ± 31.1 |

Definition of abbreviations: AAD = α1-antitrypsin disease; BLT = bilateral lung transplant; CF = cystic fibrosis; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DTH = delayed-type hypersensitivity; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; OLT = orthoptopic lung transplantation; PRA = panel of reactive antibodies; SLT = single lung transplant.

Averaged from multiple determinations, expressed in units of 10−4 inches.

Data unavailable.

Indicates ECMO support, index unable to be calculated, surrogate used.

Thirty-three patients tested for pretransplant for reactivity to col(V) were subsequently transplanted; early functional data are presented here correlated to disease, type of transplant, PRA, and pretransplant trans-vivo (TV)–DTH response. A threshold of ⩾25 × 10−4 inches was used to define a positive TV-DTH response. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support is indicated by the surrogate marker, ⩽50.

Figure 4.

PaO2/FiO2 as a function of trans-vivo delayed-type hypersensitivity (TV-DTH) response and disease type. Subgroup analyses based on least squares means with associated SEM. Dotted line represents an index value of 200, the threshold for primary graft dysfunction diagnosis. Functional data presented from collagen V TV-DTH–reactive versus nonreactive patients (n = 33). Statistical analyses were performed via a least squares mean repeated-measures analysis of variance; *P ⩽ 0.05; **P ⩽ 0.01. Open squares, DTH negative (n = 24); solid squares, DTH positive (n = 9).

To best determine which pretransplant risk factors are associated with the development of PGD (index < 200 at 72 h) in our study population, we undertook a univariate risk factor analysis. Parameters included in the model were recipient age, primary diagnosis, transplant type (single lung vs. bilateral lung), HLA matching, PRA, TV-DTH status, ischemic time, and six-minute-walk distance. Of these eight parameters, only two were able to significantly predict the development of PGD in the study population: cold ischemic time (P = 0.01) and TV-DTH reactivity toward col(V) greater than 25 × 10−4 inches (P = 0.005).

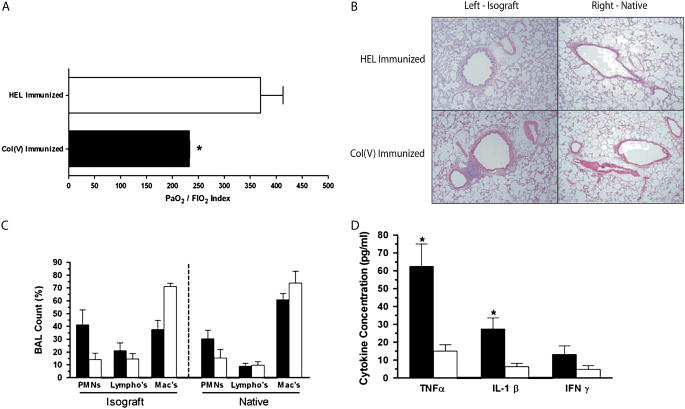

To confirm the effects of col(V)-specific memory responses on lung transplants in a model where alloreactive T and B cells are excluded, a rat lung isograft model was used. Two treatment groups were compared: control (HEL) immunized and experimental (col[V]) immunized. Seventy-two hours post-transplantation, selective BAL was performed in the native and transplanted lung, arterial blood was sampled for PaO2/FiO2 index calculation, and the transplanted lung harvested and processed by hematoxylin-and-eosin staining. Control rats, which received a WKY isograft but were immunized against an immunologically irrelevant antigen (HEL), showed PaO2/FiO2 values near normal human indices (Figure 5A). In addition, there was minimal perivascular and peribronchiolar infiltration of mononuclear cells (Figure 5B). However, rats immunized with col(V) showed significantly impaired gas exchange at 72 hours, compared with HEL-immunized rats (P = 0.008) as measured by the PaO2/FiO2 index (Figure 5A). In addition, there was severe infiltration of mononuclear cells in the peribronchiolar and perivascular interstitium (Figure 5B), in the areas previously shown to contain exposed col(V) by immunohistochemistry (10). This infiltration was extensive enough to mimic moderate acute cellular rejection with small foci of bronchially associated lymphoid aggregates beginning to organize in the perivascular stroma. No infiltration was observed in the native right lungs of col(V)- or HEL-immunized rats (Figure 5B, right), indicating that the pathology mediated by col(V)-specific effector memory T cells is confined to the ischemically injured lung graft. Furthermore, BAL fluid (Figure 5C) showed disruption of the normally alveolar macrophage–dominated cellular milieu, and replacement with a polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN)-dominant population in the col(V)-immunized lung isograft (P > 0.05). Analysis of BAL fluid showed marked elevation of TNF-α (P = 0.04) and IL-1β (P = 0.04) in the col(V)-immunized isograft when compared with HEL isografts (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Functional, histologic, and biochemical variation among orthotopic rat lung transplant cohorts. (A) Comparison of PaO2/FiO2 index among treatment rat groups, showing severe (P = 0.008) functional decline after collagen V (col[V]) immunization (n = 3) compared with hen egg lysozyme (HEL)–immunized (n = 4) control rats at 72 hours post-transplantation. *P-value significant compared with HEL. (B) Seventy-two-hour histology is also shown. Col(V)-immunized animals have significant mononuclear cell infiltration around small airways and vascular structures consistent with acute rejection (grade 2). Data are representative of three to four rats in each group (×10 original magnification). Some perivascular and peribronchiolar infiltration is seen in HEL-immunized animals, likely due to complete Freund's adjuvant exposure. (C) Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of native and isograft lungs at 72 hours post-transplantation shows disruption of the normally macrophage-dominated cellular differential. A trend (P > 0.05) toward more polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) was seen in the col(V)-immunized isograft, but not in the native lung or HEL-immunized animals. (D) Cytokine analysis in BAL fluid from col(V)- and HEL-immunized animals, 72 hours post-transplantation, was also performed. Col(V)-immunized isograft BAL fluid contained significantly more tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (P = 0.04) and IL-1β (P = 0.04) when compared with HEL-immunized isograft counterparts (Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric data). *P value significant compared with HEL. (C and D) Solid bars, col(v); open bars, HEL.

DISCUSSION

Although it is the only definitive therapy for persons with end-stage respiratory failure (22), lung (and heart–lung) transplantation continues to have the poorest graft and patient survival of any solid organ transplantation category (registry data available at http://www.optn.org/latestData/step2.asp). In part, this is due to the high incidence (11–25%) of PGD, even in well-preserved “ideal organs” (23–26). The use of the PaO2/FiO2 index, or P/F ratio, for assessing acute lung dysfunction from acute lung injury (index ⩽ 300) and adult respiratory distress syndrome (index ⩽ 200) is the accepted standard (27), and the use of the P/F ratio in assessing PGD has recently been established (23, 28). In this study, we applied the P/F ratio as a measure of acute lung injury/PGD and found a significant correlation of PGD with anti-col(V) immune status before transplantation, a novel finding with a number of important implications for lung transplantation.

Th-17– and monocyte-dependent immunoreactivity directed toward col(V) was significantly associated with poor early lung allograft function. What is unclear is the complete immune mechanism resulting in graft dysfunction. The TV-DTH assay, which provides a readout of cell-mediated (T-cell dependent) immune memory (16, 18, 19) to col(V), may be only a surrogate marker of an underlying process that is humoral and complement mediated. Although there is likely a humoral component to col(V)-specific autoimmunity, the idea that graft dysfunction is due entirely to antibody- and complement-mediated pathways seems unlikely given the severe mononuclear cell infiltration in isografts placed in col(V)-immunized rats (Figure 5B) and the fact that the C4d deposition was not detected in the damaged lungs (D.S.W., unpublished observations). The potential for antibody-mediated injury should not be overlooked, however. The fact that col(V) becomes exposed to detection by immunohistochemistry and anti-col(V) antibody during ischemia–reperfusion injury indicates that this normally cryptic antigen (8, 9) could provide a target in the extracellular matrix for col(V)-specific antibody deposition. Ongoing serum transfer studies in the rat isograft model will be able to directly address the role of antibodies in this process.

PGD has been closely associated with innate immunity (29), and with CD14 polymorphisms in particular (30). Therefore, we must consider the unique collaboration that exists between human memory Th-17 cells and CD14+ macrophages as a possible link between adaptive and innate immunity. Bharat and colleagues, using PBMCs from patients who had received a lung transplant, demonstrated a key role for immune regulation by CD4+CD25+ T-regulatory cells in preventing outgrowth of col(V)-reactive Th-1 (IFN-γ) effector cells in long-term cultures (31, 32). However, this report did not address the mechanisms of T-effector function in vivo or the role of IL-17. In contrast to the Th-1 bias seen in long-term col(V)-reactive CD4 T-cell lines, our preliminary characterization of the col(V)-specific memory T cells that mediate pretransplant TV-DTH reactivity in fresh PBMCs indicates that they are an unusual type of CD4+ T cell that rapidly induces production of TNF-α and IL-1β by CD14+ monocyte accessory cells. Specifically, monocyte-derived TNF-α, IL-1β, and T-cell–derived IL-17, but not T-cell–derived IFN-γ, were required for the DTH response to col(V) in the current study, confirming our previous analysis of post-transplant responses and BOS (14).

Because graft dysfunction in col(V)-reactive individuals was evident so rapidly, within 6 hours in most cases, one might argue that the likelihood of a purely cell-mediated phenomenon is questionable. Indeed, the classical time course for onset of Th-1–dependent type IV DTH is 48–72 hours (33). However, the kinetics of Th-17–dependent DTH responses in a macrophage-rich organ such as the lung are unknown. Because IL-17 is known to be a chemotactic factor for neutrophil recruitment (34), and a strong stimulus for monocyte/macrophage TNF-α and IL-1β production (35), Th-17 memory cells would appear to be ideally suited to promote innate immune responses in the transplanted lung, in a rapid response, consistent with the observed time of PGD onset. One further contributing factor might be the alloimmune status of the patient. Col(V) TV-DTH status and the risk of PGD appeared to be unrelated to HLA antibody sensitization (PRA); however, it should be pointed out that we did not test for allosensitization using T-cell–based assays (36), and thus cannot rule out a contribution of T-cell allosensitization to PGD.

Memory T cell responses directed toward col(V) were present disproportionately in patients with IPF. Historically, patients with IPF have the poorest long-term survival after lung transplant, and often have significant difficulty with thromboembolic complications in the perioperative period (37). Although evidence of anticollagen type I and III antibody (38), and hypercoagulability due to antiphospholipid antibodies and tissue factor (39–41) may help explain these thrombotic complications, other factors may contribute to the poor graft function in these patients. Our data suggest that PGD in patients with IPF may, in part, be attributable to the increased incidence of preexisting col(V) reactivity. Interestingly, however, the worst PGD cases were observed in the col(V)-reactive patients with non-IPF diagnoses, suggesting that patients with IPF may be able to partially attenuate the anti-col(V) immune mechanisms as a compensatory component of their primary disease process.

Our observations in human patients were confirmed in the rat lung isograft model, showing similar deficits in oxygen transfer at 72 hours post-transplantation. This model illustrates that, even in the absence of alloreactivity, a memory response to col(V) is adequate to cause measurable graft dysfunction. Furthermore, we observed a mononuclear cellular infiltration in the perivascular and peribronchiolar stroma, which was associated with loss of the normal homeostatic, macrophage-dominated BAL cell differential. The preponderance of PMNs in the col(V)-immunized lung isograft (Figure 5C) may partly be explained by the increased local expression of IL-17, a potent neutrophil and monocyte chemotactic agent (42). Indeed, there is a trend toward higher IL-17 mRNA levels in mediastinal lymph nodes 72 hours after isograft lung transplantation in col(V)- versus HEL-immunized rats (D.S.W., unpublished observations); these preliminary studies need to be confirmed by ELISA and enzyme-linked immunospot assay analysis, when IL-17 rat-specific antibodies become available. In our previous study (14), TNF-α production by monocytes was IL-17 dependent in PBMC cultures of col(V)-reactive transplant patients. Furthermore, our observation of TV-DTH swelling dependence on TNF-α and IL-1β was validated by the marked elevation in isograft BAL fluid of col(V)-immunized rats, again highlighting the importance of CD4+ T-cell and monocyte/macrophage interactions.

Emerging from this study and our prior reports is the role of IL-17 and monocytes/macrophages in the autoimmune response to col(V) after lung transplantation (10, 14). Th-17 cells have been shown to have key roles in autoimmune diseases and the cytokine requirements for induction of this cell type in humans include both IL-6 and IL-1β (13, 43). Notably, the report from Acosta-Rodriguez and colleagues (13) demonstrated that monocytes were the key antigen presenting cells (APCs) able to induce Th-17 cells, and that Th-17 induction was maximal in the presence of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 ligands and allogeneic monocytes. This finding may be relevant to the immunopathogenesis of graft injury post–lung transplantation. Rejection in the early post-transplant period is believed to be initiated by interactions of recipient-derived T cells with donor-derived lung APCs. Although dendritic cells are the most potent APCs, the lung is rich in monocytes/macrophages and depletion of these cells in the donor lung before transplantation was associated with decreased local induction of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α (44). The donor lung is frequently colonized with microbial pathogens that are a rich source of TLR ligands (45), and lung transplantation itself results in exposure of antigenic col(V) (10). We hypothesize that the combination of donor lung monocyte/macrophage-induced alloimmunity that is enhanced by TLR ligands may result in high local levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1 and IL-6, which may potentiate PGD in col(V)-presensitized patients, while promoting de novo development of Th-17 cells reactive to col(V) in patients not previously col(V) reactive, thus predisposing to BOS (14). Ongoing experiments will test this theory.

In summary, we have shown that memory T cells specific to col(V) can be identified in peripheral blood and hilar lymph nodes before transplantation. We have also demonstrated that the preexistence of these cells, together with macrophage accessory cells as mediators of DTH-like reactions that depend on IL-17 and the monokines IL-1β and TNF-α, correlate to PGD in both clinical lung transplantation and rat lung isograft models. Although col(V) presensitization was seen in all patient disease groups, patients with IPF were most predisposed to cell-mediated autoimmunity to col(V); this new finding may be of interest to the study of IPF etiology. On the basis of these findings, efforts to desensitize patients with IPF and other patients shown to have preexisting cellular reactivity to col(V) before transplant may be warranted to diminish lung allograft dysfunction in the early post-transplant period. We hypothesize that therapies aimed at the depletion, or regulation (21, 46), of col(V)-specific memory T cells by the use of desensitization protocols while waitlisted, as well as perioperative treatments to diminish proinflammatory cytokine production by CD14+ cells in the lung, may reduce the risk of PGD and early transplant loss.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Nilto De Oliveira for his support in providing patient samples for confirmatory study.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 AI48624 (W.J.B., R.B.L., L.D.H., E.J.-G., K.C.M.), R21 A1049900 (W.J.B., L.D.H., E.J.-G.), RO1 AR47746 (D.S.G.), RO1 HL60797 (K.Y., K.M.H., D.S.W.), RO1 HL/AI67177 (D.S.W.), R21 HL069727 (D.S.W.), HL081350 (D.S.W.), HL/Al67177 (D.S.W.), and by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Arthritis Foundation (D.D.B.). The Center for Immunobiology is supported in part by the Indiana Genomics Initiative of Indiana University, which is supported in part by Lilly Endowment, Inc.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1901OC on January 3, 2008

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Mares DC, Heidler KM, Smith GN, Cummings OW, Harris ER, Foresman B, Wilkes DS. Type V collagen modulates alloantigen-induced pathology and immunology in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000;23:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sumpter TL, Wilkes DS. Role of autoimmunity in organ allograft rejection: a focus on immunity to type V collagen in the pathogenesis of lung transplant rejection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;286:L1129–L1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christie JD, Kotloff RM, Pochettino A, Arcasoy SM, Rosengard BR, Landis JR, Kimmel SE. Clinical risk factors for primary graft failure following lung transplantation. Chest 2003;124:1232–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rolls HK, Kishimoto K, Dong VM, Illigens BM, Sho M, Sayegh MH, Benichou G, Fedoseyeva EV. T-cell response to cardiac myosin persists in the absence of an alloimmune response in recipients with chronic cardiac allograft rejection. Transplantation 2002;74:1053–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dragun D, Muller DN, Brasen JH, Fritsche L, Nieminen-Kelha M, Dechend R, Kintscher U, Rudolph B, Hoebeke J, Eckert D, et al. Angiotensin II type 1-receptor activating antibodies in renal-allograft rejection. N Engl J Med 2005;352:558–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azimzadeh AM, Pfeiffer S, Wu GS, Schroder C, Zhou H, Zorn GL 3rd, Kehry M, Miller GG, Rose ML, Pierson RN 3rd. Humoral immunity to vimentin is associated with cardiac allograft injury in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant 2005;5:2349–2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Kuppevelt TH, Veerkamp JH, Timmermans JA. Immunoquantification of type I, III, IV and V collagen in small samples of human lung parenchyma. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 1995;27:775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linsenmayer TF, Gibney E, Igoe F, Gordon MK, Fitch JM, Fessler LI, Birk DE. Type V collagen: molecular structure and fibrillar organization of the chicken alpha 1(V) NH2-terminal domain, a putative regulator of corneal fibrillogenesis. J Cell Biol 1993;121:1181–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birk DE, Fitch JM, Babiarz JP, Linsenmayer TF. Collagen type I and type V are present in the same fibril in the avian corneal stroma. J Cell Biol 1988;106:999–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida S, Haque A, Mizobuchi T, Iwata T, Chiyo M, Webb TJ, Baldridge LA, Heidler KM, Cummings OW, Fujisawa T, et al. Anti-type V collagen lymphocytes that express IL-17 and IL-23 induce rejection pathology in fresh and well-healed lung transplants. Am J Transplant 2006;6:724–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haque MA, Mizobuchi T, Yasufuku K, Fujisawa T, Brutkiewicz RR, Zheng Y, Woods K, Smith GN, Cummings OW, Heidler KM, et al. Evidence for immune responses to a self-antigen in lung transplantation: role of type V collagen-specific T cells in the pathogenesis of lung allograft rejection. J Immunol 2002;169:1542–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. T(h)-17 cells in the circle of immunity and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol 2007;8:345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Napolitani G, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Interleukins 1beta and 6 but not transforming growth factor-beta are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing human T helper cells. Nat Immunol 2007;8:942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burlingham W, Love RB, Jankowska-Gan E, Haynes LD, Xu Q, Bobadilla JL, Meyer KC, Hayney MS, Braun RK, Greenspan DS, et al. IL-17–dependent cellular immunity to collagen type V predisposes to obliterative bronchiolitis in human lung transplants. J Clin Invest 2007;3498–3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Carrodeguas L, Orosz CG, Waldman WJ, Sedmak DD, Adams PW, VanBuskirk AM. Trans vivo analysis of human delayed-type hypersensitivity reactivity. Hum Immunol 1999;60:640–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.VanBuskirk AM, Burlingham WJ, Jankowska-Gan E, Chin T, Kusaka S, Geissler F, Pelletier RP, Orosz CG. Human allograft acceptance is associated with immune regulation. J Clin Invest 2000;106:145–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burlingham WJ, Jankowska-Gan E. Mouse strain and injection site are crucial for detecting linked suppression in transplant recipients by trans-vivo DTH assay. Am J Transplant 2007;7:466–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burlingham W, Jankowska-Gan E, VanBuskirk AM, Pelletier R, Orosz C. Delayed type hypersensitivity responses. In: Lotze MT, Thomson AW, editors. Measuring immunity: basic science and clinical practise. London, UK: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 407–418.

- 19.Rodriguez DS, Jankowska-Gan E, Haynes LD, Leverson G, Munoz A, Heisey D, Sollinger HW, Burlingham WJ. Immune regulation and graft survival in kidney transplant recipients are both enhanced by human leukocyte antigen matching. Am J Transplant 2004;4:537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yasufuku K, Heidler KM, O'Donnell PW, Smith GNJ, Cummings OW, Foresman BH, Fujisawa T, Wilkes DS. Oral tolerance induction by type V collagen downregulates lung allograft rejection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001;25:26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizobuchi T, Yasufuku K, Zheng Y, Haque MA, Heidler KM, Woods K, Smith GN, Jr., Cummings OW, Fujisawa T, Blum JS, et al. Differential expression of Smad7 transcripts identifies the CD4+CD45RC high regulatory T cells that mediate type V collagen-induced tolerance to lung allografts. J Immunol 2003;171:1140–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Perrot M, Chaparro C, McRae K, Waddell TK, Hadjiliadis D, Singer LG, Pierre AF, Hutcheon M, Keshavjee S. Twenty-year experience of lung transplantation at a single center: influence of recipient diagnosis on long-term survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;127:1493–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christie JD, Carby M, Bag R, Corris P, Hertz M, Weill D. Report of the ISHLT Working Group on Primary Lung Graft Dysfunction part II: definition. A consensus statement of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:1454–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christie JD, Bavaria JE, Palevsky HI, Litzky L, Blumenthal NP, Kaiser LR, Kotloff RM. Primary graft failure following lung transplantation. Chest 1998;114:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christie JD, Sager JS, Kimmel SE, Ahya VN, Gaughan C, Blumenthal NP, Kotloff RM. Impact of primary graft failure on outcomes following lung transplantation. Chest 2005;127:161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyers BF, de la Morena M, Sweet SC, Trulock EP, Guthrie TJ, Mendeloff EN, Huddleston C, Cooper JD, Patterson GA. Primary graft dysfunction and other selected complications of lung transplantation: a single-center experience of 983 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129:1421–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS: definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149:818–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitson BA, Nath DS, Johnson AC, Walker AR, Prekker ME, Radosevich DM, Herrington CS, Dahlberg PS. Risk factors for primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;131:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carter YM, Davis RD. Primary graft dysfunction in lung transplantation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2006;27:501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer SM, Klimecki W, Yu L, Reinsmoen NL, Snyder LD, Ganous TM, Burch L, Schwartz DA. Genetic regulation of rejection and survival following human lung transplantation by the innate immune receptor CD14. Am J Transplant 2007;7:693–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bharat A, Fields RC, Steward N, Trulock EP, Patterson GA, Mohanakumar T. CD4+25+ regulatory T cells limit Th1-autoimmunity by inducing IL-10 producing T cells following human lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 2006;6:1799–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bharat A, Fields RC, Trulock EP, Patterson GA, Mohanakumar T. Induction of IL-10 suppressors in lung transplant patients by CD4+25+ regulatory T cells through CTLA-4 signaling. J Immunol 2006;177:5631–5638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuji RF, Geba GP, Wang Y, Kawamoto K, Matis LA, Askenase PW. Required early complement activation in contact sensitivity with generation of local C5-dependent chemotactic activity, and late T cell interferon gamma: a possible initiating role of B cells. J Exp Med 1997;186:1015–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laan M, Cui ZH, Hoshino H, Sjostrand M, Gruenert DC, Skoogh BE, Linden A. Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via CX-C chemokine release in the airways. J Immunol 1999;162:2347–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jovanovic DV, Di Battista JA, Martel-Pelletier J, Jolicoeur FC, He Y, Zhang M, Mineau F, Pelletier JP. IL-17 stimulates the production and expression of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-beta and TNF-alpha, by human macrophages. J Immunol 1998;160:3513–3521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heeger PS, Greenspan NS, Kuhlenschmidt S, Dejelo C, Hricik DE, Schulak JA, Tary-Lehmann M. Pretransplant frequency of donor-specific, IFN-gamma-producing lymphocytes is a manifestation of immunologic memory and correlates with the risk of posttransplant rejection episodes. J Immunol 1999;163:2267–2275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nathan SD, Barnett SD, Urban BA, Nowalk C, Moran BR, Burton N. Pulmonary embolism in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis transplant recipients. Chest 2003;123:1758–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakos G, Adams A, Andriopoulos N. Antibodies to collagen in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 1993;103:1051–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asherson RA, Cervera R. Review: antiphospholipid antibodies and the lung. J Rheumatol 1995;22:62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujii M, Hayakawa H, Urano T, Sato A, Chida K, Nakamura H, Takada A. Relevance of tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor for hypercoagulable state in the lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thromb Res 2000;99:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magro CM, Klinger DM, Adams PW, Orosz CG, Pope-Harman AL, Waldman WJ, Knight D, Ross P Jr. Evidence that humoral allograft rejection in lung transplant patients is not histocompatibility antigen-related. Am J Transplant 2003;3:1264–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Afzali B, Lombardi G, Lechler RI, Lord GM. The role of T helper 17 (Th17) and regulatory T cells (Treg) in human organ transplantation and autoimmune disease. Clin Exp Immunol 2007;148:32–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, McKenzie BS, Blumenschein WM, Mattson JD, Basham B, Smith K, Chen T, Morel F, et al. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat Immunol 2007;8:950–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sekine Y, Bowen LK, Heidler KM, Van Rooijen N, Brown JW, Cummings OW, Wilkes DS. Role of passenger leukocytes in allograft rejection: effect of depletion of donor alveolar macrophages on the local production of TNF-alpha, T helper 1/T helper 2 cytokines, IgG subclasses, and pathology in a rat model of lung transplantation. J Immunol 1997;159:4084–4093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Avlonitis VS, Krause A, Luzzi L, Powell H, Phillips JA, Corris PA, Gould FK, Dark JH. Bacterial colonization of the donor lower airways is a predictor of poor outcome in lung transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2003;24:601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yasufuku K, Heidler KM, Woods KA, Smith GN Jr, Cummings OW, Fujisawa T, Wilkes DS. Prevention of bronchiolitis obliterans in rat lung allografts by type V collagen-induced oral tolerance. Transplantation 2002;73:500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]