Abstract

Recombinant N-myristoyltransferase of Plasmodium falciparum (termed PfNMT) has been used in the development of a SPA (scintillation proximity assay) suitable for automation and high-throughput screening of inhibitors against this enzyme. The ability to use the SPA has been facilitated by development of an expression and purification system which yields considerably improved quantities of soluble active recombinant PfNMT compared with previous studies. Specifically, yields of pure protein have been increased from 12 μg·l−1 to >400 μg·l−1 by use of a synthetic gene with codon usage optimized for expression in an Escherichia coli host. Preliminary small-scale ‘piggyback’ inhibitor studies using the SPA have identified a family of related molecules containing a core benzothiazole scaffold with IC50 values <50 μM, which demonstrate selectivity over human NMT1. Two of these compounds, when tested against cultured parasites in vitro, reduced parasitaemia by >80% at a concentration of 10 μM.

Keywords: benzothiazole, codon optimization, inhibition, N-myristoylation, Plasmodium falciparum, scintillation proximity assay (SPA)

Abbreviations: ARF, ADP-ribosylation factor; CaNMT, Candida albicans NMT; DTT, dithiothreitol; Fmoc/tBu, fluoren-9-ylmethoxycarbonyl/t-butyl; HsNMT, Homo sapiens NMT; IMAC, immobilized metal affinity; LB, Luria–Bertani; LmNMT, Leishmania major NMT; NMT, myristoyl CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase; PfARF, Plasmodium falciparum ARF; PfEMP, Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein; PfNMT, Plasmodium falciparum NMT; SPA, scintillation proximity assay; SPPS, solid-phase peptide synthesis; TbNMT, Trypanosoma brucei NMT

INTRODUCTION

Malaria is a devastating disease with an estimated 300–500 million cases and >1 million deaths per year [1]. Resistance to established anti-malarial drugs is increasing the need for the development of new compounds to combat the disease. In the present paper we describe investigations into the N-myristoyltransferase of Plasmodium falciparum as a potential target for development of novel chemotherapeutics.

NMT [myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase (EC 2.3.1.97)] is an enzyme which catalyses the co-translational transfer [2] of the fatty acid myristate (C14:0) from myristoyl-CoA to the N-terminal glycine of target eukaryotic proteins, as well as to viral and bacterial proteins myristoylated within the host cell [3–5]. The reaction proceeds via an ordered Bi Bi mechanism [6] in which myristoyl-CoA initially binds, followed by a putative structural rearrangement and binding of the N-terminus of the protein substrate. Myristate transfer to the N-terminal glycine of the protein substrate and stepwise dissociation of CoA followed by the myristoylated protein completes the reaction [7,8].

NMT has been extensively investigated as a drug target against pathogenic fungi (reviewed in [9,10]) and also identified as a potential target in kinetoplastid parasites [11] as well as a novel anti-cancer agent [12–15]. Genetic analyses of NMT have shown recessive lethality in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, whereas NMT is an essential gene in Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans [16,17], Trypanosoma brucei and Leishmania major [18]. Comparative analyses of human and fungal NMTs have shown that the peptide pocket is less well conserved than the myristoyl-CoA-binding site [19]. Although myristoyl-CoA analogues have been shown to have anti-viral activity [20], selective inhibition can be best achieved by targeting the peptide-binding pocket. For example, inhibitors of the NMT peptide-binding pocket in pathogenic fungi are capable of inhibiting C. albicans NMT (CaNMT) with IC50 values in the nanomolar range [10,21–23] and show >1000-fold selectivity over human NMTs. There are two NMT genes in humans, (Homo sapiens N-myristoyltransferase 1 and 2 [24,25]). Their protein products HsNMT1 and HsNMT2 show 73% identity with each other and 40–50% identity with the NMTs of C. albicans, T. brucei and P. falciparum. Investigations into inhibitors of HsNMT1 have identified a family of compounds based around a cyclohexyl-octahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine scaffold with IC50 values in the low micromolar range [26]. NMT activity has also been studied in kinetoplastid parasites. Establishment of robust expression and purification protocols for recombinant forms of T. brucei NMT (TbNMT) and L. major NMT (LmNMT) in Escherichia coli has enabled compounds to be tested for inhibition of these enzymes, in a ‘piggy-back’ approach [11], leading to identification of inhibitors selective for TbNMT [27]. In comparison, only low expression of recombinant P. falciparum NMT (PfNMT) (12 μg·l−1) has been reported to date [28] and this has limited the initiation of similar studies. However, like TbNMT and LmNMT, PfNMT has considerable potential as an anti-malarial drug target. PfNMT is encoded as a single copy gene (plasmo DB accession number PF14_0127) with detectable mRNA in the asexual blood stage forms and the recombinant protein shows differential inhibition profiles compared with HsNMT1 [25]. A range of N-myristoylated substrates from P. falciparum {including GAP (gliding-associated protein; PFL1090w) [29], GRASP (PF10_0168) [30] and CDPK (PFB0815w) [31]} have been identified biochemically. In addition, more than 40 potential substrates with a high likelihood of being N-myristoylated have been identified by bioinformatic and biochemical predictions; these include ARFs (ADP-ribosylation factors), CDPKs and several PfEMP1s (P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein) [32]. The presence of these known and predicted substrates of PfNMT suggests that inhibition of this enzyme would disrupt a range of biochemical pathways, ultimately resulting in loss of parasite viability.

To further study the potential of PfNMT as a drug target, we describe in the present paper the improved expression and purification of a recombinant form of the enzyme from E. coli, utilizing a synthetic codon-optimized PfNMT gene. Furthermore, we also report the development of a SPA (scintillation proximity assay) amenable to high-throughput screening and demonstrate how this assay has been used for the identification of inhibitors showing activity against both recombinant PfNMT and the cultured asexual stages of P. falciparum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Codon optimization for PfNMT expression in E. coli

The codon usage in the native PfNMT gene was modified to give a new synthetic gene with codons optimal for expression in E. coli. The synthetic gene was designed with the help of a Perl script program CODOP which allows codon optimization for a given host organism [33]. The program allowed the insertion of desired restriction sites and generated 40-mer oligonucleotides for both strands of the gene with a melting temperature for each of the 20 nucleotide overlaps of approx. 60 °C. The oligonucleotides were checked for the presence of repeats, stem–loops and overlaps using the Genetics Computer Group software package (version 8-Unix). A total of 60 oligonucleotides were obtained; the two end fragments were longer (49 and 61 nucleotides) to include the restriction sites of BamHI and EcoRI for subsequent subcloning. The sequence was then assembled and amplified as described in [34], achieving a reduction in AT content from 73% to 60%. The amplified fragment was cloned into the vector pTrcHisA (Invitrogen) and the sequence was confirmed. The resulting plasmid pTrcNMT was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS for expression studies.

Overexpression and purification of recombinant PfNMT, HsNMT1 and CaNMT

Expression of N-terminally His6-tagged PfNMT from pTrcNMT was induced in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS in the presence of 100 μg·ml−1 ampicillin. A single bacterial colony was grown for 16 h in LB (Luria–Bertani) broth at 37 °C with shaking at 220 rev./min. Inoculation (1:20) of fresh LB broth was followed by growth at 37 °C at 220 rev./min to a D600 of 0.6. The culture temperature was reduced to 30 °C before induction with 0.1 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside) and growth at 30 °C for 4–5 h. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (14000 g, 10 min) and resuspended in cell lysis buffer [300 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM DTT (dithiothreitol) and 20 mM imidazole (pH 7.0) supplemented with 2% (v/v) Triton X-100] in the presence of EDTA-free mini Complete™ protease inhibitors (Roche). Cells were then treated with lysozyme (1 mg·ml−1, 30 min on ice), followed by sonication on ice (three rounds of 2×10 s pulses at 15 W). The soluble fraction was isolated by two rounds of centrifugation (40000 g, 4 °C) and recombinant His6-tagged protein recovered by IMAC (immobilized metal affinity) resin using Ni-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's protocol, with elution by 500 mM imidazole. Fractions containing NMT activity were pooled and buffer-exchanged into 50 mM NaCl, 100 mM sodium phosphate and 5 mM DTT, (pH 7.0) by sequential concentration and dilution (three rounds on Centricon YM-30 spin columns; Millipore) to a final volume of 2 ml. The sample was filtered (0.44 μM filter) before applying to a Sephacryl S-100 column connected to an AKTAFPLC system (GE Healthcare), maintained at 4 °C, using at a flow rate of 0.2 ml·min−1. Fractions containing NMT activity were pooled, diluted to 50 ml in 50 mM sodium phosphate and 5 mM DTT (pH 6.5) and applied using a 50 ml Superloop (GE Healthcare) to a ReSOURCE S strong cation-exchange column. Elution was conducted using a 0–1 M NaCl gradient in the same buffer at a flow rate of 2 ml·min−1. Products were analysed by SDS/PAGE and the identity of the major band (approx. 50 kDa) confirmed as PfNMT by MALDI–TOF (matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization–time-of-flight) MS.

Plasmids encoding HsNMT1 (in pET20b) and CaNMT (in pET11c) were provided by Pfizer. Recombinant forms of these proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS as above and cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris/HCl and 2 mM EGTA (pH 8.6) (for HsNMT) or 20 mM Tris/HCl and 1 mM DTT (pH 7.4) (for CaNMT). For both soluble lysates, NMT activity was enriched by anion-exchange using a 30 ml DEAE Sepharose column, with elution over a 0–1 M NaCl gradient at a flow rate of 3 ml·min−1. All NMTs were stored in 25% glycerol at −20 °C.

NMT activity and inhibition assay

Biotinylated peptide substrates based on the N-terminal sequence of P. falciparum ARF1 (PfARF1) were prepared by SPPS (solid-phase peptide synthesis) using standard Fmoc/tBu (fluoren-9-ylmethoxycarbonyl/t-butyl) chemistry [35]. The peptides GLYVSRLFNRLFQKK(biotin)-NH2 and GLYVSRLFNRLFQK(biotin)-NH2 (PfARFlong and PfARFshort respectively) were synthesized, purified by reverse-phase HPLC using a C18 column (Waters) and freeze-dried. Controls in which the N-terminal glycine residue was replaced by an alanine residue were also prepared. These substrates were used to develop a SPA for NMT activity amenable to a 96-well plate format. [3H]Myristoyl-CoA (GE Healthcare) was supplemented with unlabelled myristoyl-CoA (Sigma) to achieve the required specific activities (generally 8 Ci·mmol−1). Recombinant enzyme was prepared as described above.

Reaction volumes of 100 μl contained equal volumes of buffer (or inhibitor), recombinant NMT, 125 nM [3H]myristoyl CoA (8 Ci·mmol−1) and 125 nM biotinylated peptide substrate. All solutions were prepared using assay buffer [30 mM Tris, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM DTT (adjusted to pH 7.4 with HCl) and 0.1% Triton X-100]. DMSO was present at a final concentration of 1% (v/v). The reactions were initiated by addition of peptide substrate after a 5 min pre-incubation and allowed to proceed for 30 min at 37 °C before termination with 100 μl of stop solution (50 mg·ml−1 SPA beads in PBS/0.05% sodium azide diluted 50 times with 1:1 0.2 M phosphoric acid buffered to pH 4.0 with NaOH and 1.5 M MgCl2). The plate was then sealed and beads allowed to settle for >8 h before scintillation counting using a Chameleon plate reader.

Km determinations

The apparent Km for the myristoyl-CoA binding of PfNMT was determined by varying the myristoyl-CoA concentration from 0 to 500 nM (8 Ci·mmol−1) at a constant peptide concentration (500 nM) and enzyme concentration using the SPA. Similarly the apparent Km for the biotinylated peptide substrates was determined over the range 78–500 nM at a constant myristoyl-CoA concentration of 250 nM. The data obtained were used to generate initial rates of reaction from which Km values were obtained using the GraFit software package (version 5.0.13, Erithacus Software: http://www.erithacus.com/grafit/index.htm). Results are the means from triplicate assays.

Inhibition assay

Inhibitors, prepared as 100 mM stock solutions in DMSO, were diluted as required in assay buffer and used to replace the 25 μl buffer fraction in the standard SPA described above. Initially, inhibitors were screened at a single concentration (50 μM) to identify the compounds which produced the most effective inhibition of the target NMT. These were then further evaluated by determination of IC50 values. Inhibitor concentrations were varied from 100 nM to 1 mM at a constant myristoyl-CoA concentration (125 nM). The resulting data were plotted using GraFit and IC50 values determined from a four-parameter fit. Each IC50 value reported is the mean obtained from triplicate assays.

Parasite culture and inhibitor testing

The asexual erythrocytic stages of P. falciparum 3D7 were cultured using a modification of the procedures of Trager and Jensen [36]. Parasites were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 0.5% AlbuMAX I (GibcoBRL), 2 mM L-glutamine, 25 mM Hepes, 24 mM NaHCO3, 25 μg·ml−1 gentamycin, 16 μg·ml−1 hypoxanthine and 1.6 mg·ml−1 glucose. Human erythrocytes were obtained from the National Blood Transfusion Service. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a haematocrit of 0.5–1% and a gas mixture of 7% CO2, 5% O2 and 88% N2. Tight synchronization was achieved using the Percoll method [37]. Schizonts, isolated by centrifugation through 70% Percoll (1000 g, 11 min), were added to fresh erythrocytes for 1 h, to allow invasion to occur, before removal of the residual schizonts by lysis with 5% (w/v) sorbitol in PBS. Percoll (70%) was prepared by mixing Percoll 9:1 with 10×PBS and mixing this at a ratio of 7:3 with RPMI 1640 medium.

Selected compounds were added to the culture medium at a final concentration of 100 μM or 10 μM with 1% (v/v) DMSO. Inhibitor-free controls, both with and without 1% DMSO, were included. Experiments were initiated with three different stages of synchronized parasites at a parasitaemia of approx. 1%. Ring stage (approx. 5 h post invasion), trophozoite stage (approx. 27 h post invasion) and schizont stage (approx. 42 h post invasion) parasites were all allowed to develop, release and re-invade new red blood cells and progress to approx. 30 h in the next cycle. This resulted in a total inhibitor exposure time of 68, 53 and 31 h for the ring, trophozoite and schizont stages respectively. At the end of each experiment, parasite morphology was examined and the numbers of infected red blood cells were determined by Giemsa staining and light microscopy, counting >2000 red blood cells per sample. The results shown are the means of a triplicate repeat.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Codon optimization improves the yield of PfNMT

In an attempt to improve heterologous expression of PfNMT in E. coli, codon optimization of PfNMT was undertaken to remove codons rarely used in E. coli. These changes also resulted in an overall reduction in AT content from 73% to 60% (see Supplementary Figure at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/408/bj4080173add.htm). Expression of soluble, active protein was achieved by creating an expression construct in which the optimized PfNMT coding sequence was cloned into the BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites of the pTrcHisA expression vector. High levels of PfNMT overexpression were also observed using pET 28a and pGEX 5X-1 expression vectors but in these cases, the proteins remained insoluble (results not shown).

A three-stage protein purification strategy was developed. Purification of PfNMT from E. coli lysates by IMAC using Ni-Sepharose was the preferred method for the capture stage of the purification. This resin is tolerant to low concentrations of DTT, which was found to reduce precipitation of PfNMT on storage. Mutation of Cys228 to a serine residue was also observed to reduce precipitation of purified PfNMT (P. W. Bowyer, unpublished work). However, as Cys228 is predicted to reside at the bottom of the peptide-binding pocket (based upon comparisons with other known NMT structures), all subsequent work was carried out with purified recombinant wild-type enzyme stabilized with DTT rather than the C228S mutant (which has the potential to alter substrate binding).

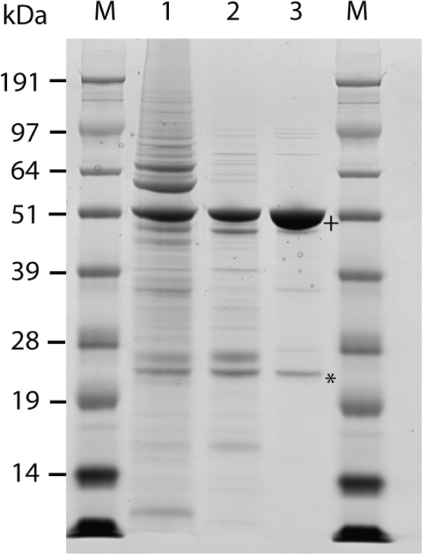

Sequential stages in the purification of PfNMT are shown in Figure 1. PfNMT is the major band following capture with Ni-Sepharose IMAC (Figure 1, lane 1; apparent molecular mass approx. 50 kDa, consistent with predictions from primary sequence analysis). Concentration of this material and subsequent separation by size-exclusion chromatography yielded a fraction containing PfNMT with a retention time consistent with a monomeric form of the enzyme. This fraction also contained some contaminating species with lower molecular masses (Figure 1, lane 2). In the absence of DTT, a second peak with a retention time consistent with a 75 kDa protein complex was also observed; this peak was eliminated in the presence of 5 mM DTT (results not shown). The final stage of the purification used cation-exchange chromatography (see the Materials and methods section) and resulted in the separation of PfNMT from all but one significant impurity (Figure 1, lane 3). This was identified by peptide mass fingerprinting as an E. coli Cap-DNA recognition protein with a predicted mass of 24 kDa. The protein band observed at 50 kDa was confirmed as PfNMT by peptide mass fingerprinting with >60% peptide coverage. The overall yield was typically 400 μg·l−1, representing a >20-fold improvement on previous methods [28]. Glycerol was added to a final concentration of 25% (v/v) in the PfNMT sample which was then stored at −20 °C. When stored in this way PfNMT remained stable for >2 years with negligible loss in activity (as tested in the SPA). Storage at 4 °C resulted in formation of a precipitate and loss of activity; this precipitation was decreased, but not eliminated, in the C228S variant. Codon optimization and the creation of synthetic P. falciparum genes have been shown to be an effective strategy for improving expression efficiency in heterologous expression systems such as Pichia pastoris [38], baculovirus [39], murine cells [40] and E. coli [41]. However, in a recent extensive study investigating ∼1000 P. falciparum open reading frames in an E. coli expression system [42], only a fraction of the selected sequences were successfully expressed (337, of which only 63 provided significant levels of soluble protein). Further investigation of sequences with little or no expression was conducted using alternative expression approaches and revealed little advantage to codon optimization (three out of 12 gave insoluble protein) and insect cell expression systems (one out of 17 proteins previously obtained in the insoluble fraction gave soluble protein). Although some success was obtained with each of these alternatives, no ideal system for expression of P. falciparum proteins could be determined. Most recently, Vedadi et al. [43] have reported the effective use of an E. coli expression platform to obtain structural information for apicomplexan proteins by attempting expression of ∼400 P. falciparum genes along with selected orthologues. The differing expression profiles of orthologous proteins in the E. coli system resulted in successful structural determinations for significantly increased numbers of the target proteins or their orthologues. Expression studies have not been conducted on other apicomplexan NMTs to date. In the present study, we have concentrated on the P. falciparum NMT and demonstrated the benefits of codon optimization for soluble protein expression from this particular gene.

Figure 1. Purification of recombinant PfNMT.

Recombinant PfNMT was enriched in three stages from E. coli soluble lysate, prepared following protein expression in a 50 litre fermenter. After pooling of fractions, products showing NMT activity from each purification stage were separated by SDS/PAGE as shown. Lane 1, capture stage using Ni-Sepharose IMAC; lane 2, intermediate purification on Sephacryl S-100 size-exclusion column; lane 3, final stage using ReSourceS cation-exchange (pooled active NMT fractions shown). M, molecular mass markers. In lane 3, the band migrating at approx. 50 kDa (+) was identified as PfNMT by peptide mass fingerprinting. The major impurity (*) was characterized by peptide mass fingerprinting and is most likely to be an E. coli Cap-DNA recognition protein (gi:2098303), consistent with the observed molecular mass of 24 kDa.

Development of a SPA for NMT activity

The N-myristoylation reaction transfers myristate from myristoyl-CoA to the N-terminus of a peptide/protein substrate. The majority of the assays developed for monitoring NMT activity have used radiolabel transfer to achieve high sensitivity with subsequent separation of product by HPLC or binding to phosphocellulose paper [27,44,45]. Although these can be successfully used to monitor inhibition of NMT, we favoured an approach more suited to high-throughput screening and later automation. For this purpose, we elected to use a SPA. The success of such an assay relies on incorporation of radiolabel into a product that can be selectively bound to the immobilized scintillant. In the case of N-myristoylation, [3H]myristate is transferred to a biotinylated peptide substrate that is bound to streptavidin-coated scintillant beads after termination of the enzymatic reaction. The presence of the scintillant in the bead eliminates the liquid handling stages required by the most similar assay reported [26] which uses streptavidin-coated 96-well plates to isolate the 3H-labelled peptide product before washing, to remove unreacted [3H]myristate, and addition of a liquid scintillant to facilitate counting.

The choice of a suitable NMT substrate was critical for successful assay development. We have previously shown that recombinant PfARF1 is a PfNMT substrate both in vitro and in vivo [28,29], whereas reconstituted N-myristoylation assays in E. coli have demonstrated that PfARF1 is also a substrate for CaNMT and HsNMT1 (results not shown). On the basis of this information, two biotinylated peptides (PfARFshort and PfARFlong; Table 1) were synthesized (by SPPS) for use as artificial PfNMT substrates. PfARFshort and PfARFlong contain residues 2–15 or 2–16 respectively of PfARF1 (omitting the N-terminal initiator methionine residue). Both peptides also contain a biotinylated lysine replacing the naturally occurring lysine as the C-terminal residue. These longer peptides were used in preference to the octapeptides used in many NMT substrate studies [46–48] to prevent the C-terminal biotinylated lysine residue from interacting with the peptide-binding pocket, thereby minimizing potential steric hindrance which could adversely affect the N-myristoylation reaction. Both peptides were confirmed as PfNMT substrates in an HPLC-based activity assay (results not shown). PfARFlong was demonstrated as the better SPA substrate in the same HPLC assay and subsequently in Km determinations using the SPA (Km of 1.2 μM ±0.4 for PfARFlong compared with a Km of 7.1 μM ±1.3 for PfARFshort).

Table 1. Peptides evaluated as substrates of PfNMT.

The peptides listed were synthesized by standard Fmoc/tBu SPPS from Rink-Amide MBHA (p-methylbenzhydrylamine) resin pre-loaded with biotinylated lysine, giving a C-terminal amide and a glycine or alanine residue as the N-terminal residue. ARF peptides are based on the N-terminal sequence of PfARF1. Km values for the substrate peptides demonstrate that ARFlong is a better substrate than ARFshort. Peptides with an alanine residue replacing a glycine residue are not substrates for PfNMT.

| Peptide sequence | Name | Km (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| GLYVSRLFNRLFQKK(biotin)-NH2 | ARFlong | 1.2±0.4 |

| GLYVSRLFNRLFQK(biotin)-NH2 | ARFshort | 7.1±1.0 |

| GSQGSKPVDTSDVK(biotin)-NH2 | PfEMP | Not a substrate |

| ALYVSRLFNRLFQKK(biotin)-NH2 | AlaARFlong | Not a substrate |

| ALYVSRLFNRLFQK(biotin)-NH2 | AlaARFshort | Not a substrate |

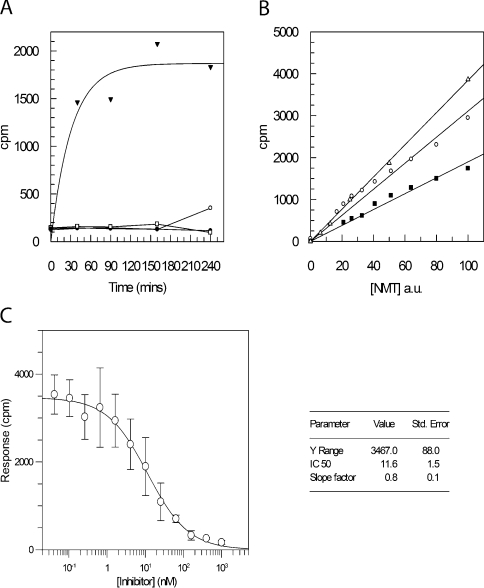

Development of the SPA was therefore initiated using the PfARFlong substrate (Figure 2). First, the dependence of radioactive incorporation on the presence of both enzyme and peptide substrate was confirmed (Figure 2A). Replacing PfARFlong with AlaARF (in which the N-terminal glycine residue is replaced by an alanine residue; Table 1) resulted in no detectable signal over background levels. This is consistent with published fungal NMT data, demonstrating that an N-terminal glycine residue is required for enzymatic N-myristoylation [48]. The SPA format also requires discontinuous sampling, taking single time-point measurements for each reaction condition and enzyme tested. In order to determine the rate-limiting concentrations of NMT required for a constant reaction rate over a standard period (allowing initial rate determinations), increasing concentrations of CaNMT, HsNMT and PfNMT were titrated over a 30 min reaction (Figure 2B). A peptide concentration was selected to allow total binding to the scintillant beads, thus eliminating competition for binding sites between unreacted biotinylated substrate and N-myristoylated product. It is possible to use larger quantities of biotinylated peptide in the reaction (greater than the bead capacity), but the decreased signal resulting from the competitive binding and the additional error dependent on SPA bead concentration made this approach less favourable. The bead capacity for PfARFlong was found to be 50–100 pmol·mg−1.

Figure 2. Development of SPA for NMT activity.

(A) The SPA was conducted with 500 nM PfARFlong substrate, 500 nM myristoyl CoA and 100 ng of PfNMT at 37 °C. Sampling was conducted at five different time points (0, 40, 90, 150 and 240 min) to monitor reaction progression. Four different samples were used in a typical reaction timecourse (▼), a reaction with no peptide (○), no NMT (●) and AlaARF peptide replacing the peptide substrate (□). (B) The concentration of NMT was titrated by serial dilution in otherwise identical reactions incubated for 30 min using 125 nM ARFlong peptide and 125 nM myristoyl-CoA, in a final volume of 100 μl. Enzyme concentration, as a percentage of the highest concentration used, is plotted against c.p.m. for reactions using CaNMT (△), PfNMT (■) and HsNMT1 (○). A close approximation to a linear fit demonstrates that enzyme concentrations can be selected so that the amount of enzyme is rate-limiting under the experimental conditions selected. a.u., arbitrary units. (C) An IC50 value for inhibitor UK-362091 with CaNMT was determined using the SPA. Inhibitor concentrations were varied from 1 μM to 42 pM in otherwise identical reactions (125 nM PfARFlong peptide, 125 nM myristoyl-CoA and 3 ng CaNMT). A plot of c.p.m., after 30 min incubation at 37 °C, against inhibitor concentration allows a four-parameter fit to derive the point at which the signal is half maximal, the IC50. Values are means±S.D. for three experiments. The IC50 value obtained is 11.6 nM (see inset), consistent with a previous evaluation of 19 nM (Pfizer, personal communication).

To further validate the optimized SPA conditions developed above, CaNMT and a known inhibitor of its activity, UK-362091 (Pfizer), were used in IC50 determination (Figure 2C). The IC50 value recorded (11.6±1.5 nM) is consistent with that previously determined at Pfizer (19 nM; Pfizer, personal communication). In addition, we have previously reported the favourable comparison of the SPA with a more laborious phosphocellulose paper binding assay, using TbNMT and a biotinylated substrate based on the T. brucei CAP5.5 protein [27]. In view of these collective results, the optimized SPA methods could now be applied to the screening of fungal NMT inhibitors against PfNMT and HsNMT1 in a 96-well plate format.

Inhibitors based around a benzothiazole scaffold can inhibit PfNMT in vitro

Initial screening for inhibition of PfNMT was conducted using five of the fungal NMT inhibitors described previously in studies on TbNMT and LmNMT [27]. Compounds CP-005240 and CP-014553, identified as inhibitors of TbNMT, were also identified as the most potent inhibitors of PfNMT in vitro (IC50 values of 360 nM and 280 nM respectively; Table 2). However, in contrast with TbNMT, relative inhibition (as compared with HsNMT1) was also achieved with UK-370485. Forty-three compounds (provided by Pfizer), each containing the same benzothiazole scaffold as UK-370485, were screened for inhibitory activity at 50 μM against both PfNMT and HsNMT1. Seven compounds showed >25% inhibitory activity against recombinant PfNMT (results not shown). IC50 values were generated for these, together with four non-benzothiazoles, previously analysed against LmNMT and TbNMT [27] (labelled * in Table 2). Table 2 shows that three benzothiazole-containing compounds (1, 4 and 7) have IC50 values <50 μM for PfNMT. All of the compounds shown in Table 2 showed some selectivity for PfNMT, with the exception of compound 2 (UK-370710) which is more inhibitory to HsNMT than PfNMT. The structures of these active benzothiazole compounds are shown in Figure 3.

Table 2. IC50 values for benzothiazole inhibitors showing activity at 50 μM.

IC50 values were determined using the SPA as described for PfNMT and HsNMT1. Compounds previously evaluated as inhibitors of TbNMT and LmNMT (denoted with *; [27]) were investigated together with benzothiazole-based inhibitors (structures 1–7 in Figure 3) that show inhibitory activity at 50 μM.

| IC50 value determined in SPA (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor | PfNMT | HsNMT |

| CP-005240 (*) | 0.36±0.04 | 1.8±0.3 |

| CP-014553 (*) | 0.28±0.12 | 1.6±0.5 |

| CP-144568 (*) | 300±78 | >1000 |

| UK-370485 (*) | 232±46 | >1000 |

| UK-145974 (*) | >1000 | >1000 |

| UK-370309 (4) | 17±1 | 331±29 |

| UK-370509 (1) | 30±3 | 286±93 |

| UK-370624 (5) | 53±5 | 656±210 |

| UK-370709 (6) | 111±7 | 711±133 |

| UK-370710 (2) | 115±9 | 28±9 |

| UK-362799 (3) | 68±4 | 309±58 |

| UK-370713 (7) | 37±4 | 329±84 |

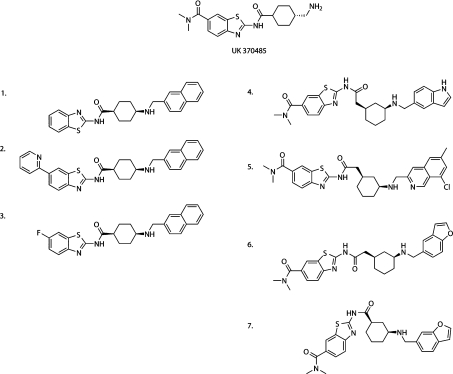

Figure 3. Structures of PfNMT inhibitors based around a benzothiazole core structure.

Structures of the seven compounds which demonstrated the highest levels of PfNMT inhibition are shown together with the parent compound UK-370485. All compounds contain a benzothiazole core. Compounds 1–3 are identical, apart from the C-6 substitution on the benzothiazole ring. Compounds 4–7 are more diverse in structure but all contain a cyclohexyl linker with 1R,3S stereochemistry (as compared with 1S,4S in compounds 1–3) and a dimethylamide as the C-6 benzothiazole substituent.

Comparison reveals that the cyclohexyl linker region between the benzothiazole functionality and the aromatic group contains two distinct regiochemistries: 1S,4S-substituted (compounds 1–3), and 1R,3S-substituted (compounds 4–7) in contrast with the starting compound UK-370485, which is trans-1,4. The effect of modifications at the C-6 position of the benzothiazole group can be seen in the reversal of selectivity between PfNMT and HsNMT1 upon change from small fluorine or hydrogen atoms (compounds 3 and 1) to the bulky pyridin-2-yl functionality (compound 2). The majority of compounds that showed inhibition of PfNMT contain the dimethylamide group which is known to form favourable binding interactions in the peptide-binding pocket of CaNMT (Pfizer). Optimization of both the C-6 substitution and the linker region is currently in progress and presents an opportunity to increase specificity and selectivity of the inhibitors.

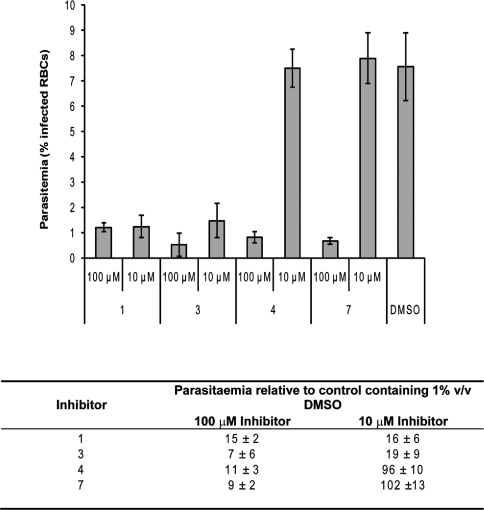

Benzothiazole-based inhibitors are toxic to cultured asexual stages of P. falciparum

Compounds 1, 3, 4 and 7 (Figure 3 and Table 2) were applied at concentrations of 100 μM and 10 μM to synchronized trophozoite stage P. falciparum 3D7 (approx. 27 h post invasion). Figure 4 shows the effect of these compounds on total parasitaemia, compared with controls containing 1% (v/v) DMSO only. In all cases, there is a significant reduction in parasitaemia at 100 μM to a level similar to the starting parasitaemia (approx. 1%). In the case of compounds 1 and 3 at 10 μM, there is an approx. 80% reduction in parasitaemia compared with the controls with DMSO only (Student's t test, P<0.03). This inhibitory effect is greater than that observed for compounds CP-005240 and CP-014553, despite the higher IC50s of the benzothiazoles in the SPA (Table 2).

Figure 4. Inhibitors of PfNMT in vitro reduce P. falciparum parasitaemia in culture.

Each inhibitor was applied to synchronized mid-trophozoite erythrocytic stages of P. falciparum (27 h) at 100 μM and 10 μM and the culture was allowed to grow until controls had reached a similar stage in the following cycle (approx. 48 h later). The total parasitaemia of each sample was evaluated by microscopic assessment of Giesma-stained blood smears. Values are means±S.D. for three experiments. All experiments were initiated at a parasitaemia of approx. 1%. RBC, red blood cell.

Changes in parasite morphology were also monitored following the application of different compound concentrations at three different start points (5 h, 27 h and 42 h post invasion), followed by continuous culture until the mid-trophozoite stage (for controls) in the next cycle (results not shown). In all samples treated with potent compounds, a short survival time was indicated by the presence of dead or dying parasites (as assessed by abnormal morphology) that progressed only a short distance through the life-cycle. However, these dead or dying parasites were infrequent; instead, the large reduction in parasitaemia between experimental samples and controls resulted from the complete absence of detectable Giemsa-stained parasites, suggesting that these cells degenerate quickly and are incapable of invasion and development. Some parasites that did not die in the strongly inhibited samples were characterized by considerably slower development, with parasites still at the ring stage when control cultures were at the trophozoite stage (>10 h delay over a 48 h time course; results not shown). In the cultures treated with 10 μM compound 1 or 3, the effect on both reduction in parasitaemia and delay in development was reduced, although not significantly. Parasites grown in the presence of 10 μM compound 4 or 7 were indistinguishable from the controls. The reasons for the striking differences in morphology observed between compounds 1 and 3 and 4 and 7 are not known but may be due to different levels of uptake and accumulation by the cultured cells. Additional off-target effects of these compounds, distinct from their inhibitory role against PfNMT, cannot be discounted at this stage.

Outlook

Previous investigations into parasitic protozoan NMT inhibitors have focused on a ‘piggy-back’ approach, using compounds originally identified as NMT inhibitors for the fungal pathogens, C. albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus [11,27]. We have also reported a small-scale study using peptide aptamers for inhibition of PfNMT [49]. The piggy-back screening approaches for PfNMT reported in the present study have identified a benzothiazole-based compound that shows anti-parasitic activity in culture, prompting testing of a range of structurally related compounds. This has led to the identification of several structurally related compounds with IC50 values <50 μM, that show some selectivity over HsNMT1 and anti-parasitic activity against cultured P. falciparum. These results compare favourably with those obtained for the highest-affinity inhibitors identified in screens of HsNMT1 by French et al. [26], using a library of 14000 compounds. Notably, one compound, containing the benzothiazole scaffold, was also found to have an IC50 <50 μM against HsNMT1, demonstrating the value of this piggy-back experimental approach in rapidly identifying drug-like molecules with a potential for further development to provide inhibitors of both HsNMT and PfNMT.

The compounds reported in the present study represent the first evidence of a related family of molecules capable of inhibiting PfNMT. All of these compounds were originally synthesized as part of an investigation into inhibitors of fungal NMTs and the discovery of compounds with high affinity for PfNMT was not presumed. The success of this piggy-back approach in discovering one family of molecules suggests that further compound optimization and validation of PfNMT as an anti-malarial target can be undertaken. Furthermore, the high-throughput screening capacity of the SPA developed as part of these studies not only creates opportunities expanding research efforts to develop an effective inhibitor of PfNMT, but also can be applied to other NMTs from different sources of therapeutic interest.

Online data

Acknowledgments

We thank Tanya Parkinson, Andy Bell and colleagues at Pfizer for technical advice and helpful discussions. This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (061343, programme grant to D. F. S.; 065514, studentship to P. W. B.) and the U.K. Medical Research Council.

References

- 1.Snow R. W., Guerra C. A., Noor A. M., Myint H. Y., Hay S. I. The global distribution of clinical episodes of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2005;434:214–217. doi: 10.1038/nature03342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilcox C., Hu J. S., Olson E. N. Acylation of proteins with myristic acid occurs cotranslationally. Science. 1987;238:1275–1278. doi: 10.1126/science.3685978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resh M. D. Fatty acylation of proteins: new insights into membrane targeting of myristoylated and palmitoylated proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1451:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maurer-Stroh S., Eisenhaber B., Eisenhaber F. N-terminal N-myristoylation of proteins: refinement of the sequence motif and its taxon-specific differences. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:523–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurer-Stroh S., Eisenhaber F. Myristoylation of viral and bacterial proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudnick D. A., McWherter C. A., Rocque W. J., Lennon P. J., Getman D. P., Gordon J. I. Kinetic and structural evidence for a sequential ordered Bi Bi mechanism of catalysis by Saccharomyces cerevisiae myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:9732–9739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farazi T. A., Waksman G., Gordon J. I. Structures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae N-myristoyltransferase with bound myristoylCoA and peptide provide insights about substrate recognition and catalysis. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6335–6343. doi: 10.1021/bi0101401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sogabe S., Masubuchi M., Sakata K., Fukami T. A., Morikami K., Shiratori Y., Ebiike H., Kawasaki K., Aoki Y., Shimma N., et al. Crystal structures of Candida albicans N-myristoyltransferase with two distinct inhibitors. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00240-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sikorski J. A., Devadas B., Zupec M. E., Freeman S. K., Brown D. L., Lu H. F., Nagarajan S., Mehta P. P., Wade A. C., Kishore N. S., et al. Selective peptidic and peptidomimetic inhibitors of Candida albicans myristoylCoA: protein N-myristoyltransferase: a new approach to antifungal therapy. Biopolymers. 1997;43:43–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1997)43:1<43::AID-BIP5>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgopapadakou N. H. Antifungals targeted to protein modification: focus on protein N-myristoyltransferase. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2002;11:1117–1125. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.8.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelb M. H., van Voorhis W. C., Buckner F. S., Yokoyama K., Eastman R., Carpenter E. P., Panethymitaki C., Brown K. A., Smith D. F. Protein farnesyl and N-myristoyl transferases: piggy-back medicinal chemistry targets for the development of antitrypanosomatid and antimalarial therapeutics. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2003;126:155–163. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selvakumar P., Pasha M. K., Ashakumary L., Dimmock J. R., Sharma R. K. Myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase: a novel molecular approach for cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2002;10:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ducker C. E., Upson J. J., French K. J., Smith C. D. Two N-myristoyltransferase isozymes play unique roles in protein myristoylation, proliferation, and apoptosis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2005;3:463–476. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selvakumar P., Lakshmikuttyamma A., Shrivastav A., Das S. B., Dimmock J. R., Sharma R. K. Potential role of N-myristoyltransferase in cancer. Prog. Lipid Res. 2007;46:1–36. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selvakumar P., Smith-Windsor E., Bonham K., Sharma R. K. N-myristoyltransferase 2 expression in human colon cancer: cross-talk between the calpain and caspase system. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2021–2026. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lodge J. K., Jackson-Machelski E., Toffaletti D. L., Perfect J. R., Gordon J. I. Targeted gene replacement demonstrates that myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase is essential for viability of Cryptococcus neoformans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:12008–12012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinberg R. A., McWherter C. A., Freeman S. K., Wood D. C., Gordon J. I., Lee S. C. Genetic studies reveal that myristoylCoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase is an essential enzyme in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;16:241–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price H. P., Menon M. R., Panethymitaki C., Goulding D., McKean P. G., Smith D. F. Myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase, an essential enzyme and potential drug target in kinetoplastid parasites. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:7206–7214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kishore N. S., Wood D. C., Mehta P. P., Wade A. C., Lu T., Gokel G. W., Gordon J. I. Comparison of the acyl chain specificities of human myristoyl-CoA synthetase and human myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:4889–4902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cordo S. M., Candurra N. A., Damonte E. B. Myristic acid analogs are inhibitors of Junin virus replication. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:609–614. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devadas B., Freeman S. K., McWherter C. A., Kishore N. S., Lodge J. K., Jackson-Machelski E., Gordon J. I., Sikorski J. A. Novel biologically active nonpeptidic inhibitors of myristoylCoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:996–1000. doi: 10.1021/jm980001q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamazaki K., Kaneko Y., Suwa K., Ebara S., Nakazawa K., Yasuno K. Synthesis of potent and selective inhibitors of Candida albicans N-myristoyltransferase based on the benzothiazole structure. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:2509–2522. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebiike H., Masubuchi M., Liu P., Kawasaki K., Morikami K., Sogabe S., Hayase M., Fujii T., Sakata K., Shindoh H., et al. Design and synthesis of novel benzofurans as a new class of antifungal agents targeting fungal N-myristoyltransferase. Part 2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:607–610. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00808-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duronio R. J., Reed S. I., Gordon J. I. Mutations of human myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase cause temperature-sensitive myristic acid auxotrophy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:4129–4133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giang D. K., Cravatt B. F. A second mammalian N-myristoyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:6595–6598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.French K. J., Zhuang Y., Schrecengost R. S., Copper J. E., Xia Z., Smith C. D. Cyclohexyl-octahydro-pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-based inhibitors of human N-myristoyltransferase-1. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;309:340–347. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.061572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panethymitaki C., Bowyer P. W., Price H. P., Leatherbarrow R. J., Brown K. A., Smith D. F. Characterisation and selective inhibition of myristoyl CoA:protein N-myristoyl transferase from Trypanosoma brucei and Leishmania major. Biochem. J. 2006;396:277–285. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunaratne R. S., Sajid M., Ling I. T., Tripathi R., Pachebat J. A., Holder A. A. Characterization of N-myristoyltransferase from Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem. J. 2000;348:459–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rees-Channer R. R., Martin S. R., Green J. L., Bowyer P. W., Grainger M., Molloy J. E., Holder A. A. Dual acylation of the 45 kDa gliding-associated protein (GAP45) in Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2006;149:113–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Struck N. S., de Souza Dias S., Langer C., Marti M., Pearce J. A., Cowman A. F., Gilberger T. W. Re-defining the Golgi complex in Plasmodium falciparum using the novel Golgi marker PfGRASP. J. Cell. Sci. 2005;118:5603–5613. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moskes C., Burghaus P. A., Wernli B., Sauder U., Durrenberger M., Kappes B. Export of Plasmodium falciparum calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 to the parasitophorous vacuole is dependent on three N-terminal membrane anchor motifs. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;54:676–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowyer P. W. Ph.D. Thesis. University of London; 2007. Studies on the N-myristoyltransferase of Plasmodium falciparum. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hale R. S., Thompson G. Codon optimization of the gene encoding a domain from human type 1 neurofibromin protein results in a threefold improvement in expression level in Escherichia coli. Protein Expression Purif. 1998;12:185–188. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Withers-Martinez C., Carpenter E. P., Hackett F., Ely B., Sajid M., Grainger M., Blackman M. J. PCR-based gene synthesis as an efficient approach for expression of the A+T-rich malaria genome. Protein Eng. 1999;12:1113–1120. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.12.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fields G. B., Noble R. L. Solid phase peptide synthesis utilizing 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl amino acids. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1990;35:161–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1990.tb00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trager W., Jensen J. B. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pasvol G., Wilson R. J., Smalley M. E., Brown J. Separation of viable schizont-infected red cells of Plasmodium falciparum from human blood. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1978;72:87–88. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1978.11719283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kocken C. H., Withers-Martinez C., Dubbeld M. A., van der Wel A., Hackett F., Valderrama A., Blackman M. J., Thomas A. W. High-level expression of the malaria blood-stage vaccine candidate Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1 and induction of antibodies that inhibit erythrocyte invasion. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:4471–4476. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4471-4476.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Withers-Martinez C., Carpenter E. P., Hackett F., Ely B., Sajid M., Grainger M., Blackman M. J. PCR-based gene synthesis as an efficient approach for expression of the A+T-rich malaria genome. Protein Eng. 1999;12:1113–1120. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.12.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Narum D. L., Kumar S., Rogers W. O., Fuhrmann S. R., Liang H., Oakley M., Taye A., Sim B. K., Hoffman S. L. Codon optimization of gene fragments encoding Plasmodium falciparum merzoite proteins enhances DNA vaccine protein expression and immunogenicity in mice. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:7250–7253. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7250-7253.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dutta S., Lalitha P. V., Ware L. A., Barbosa A., Moch J. K., Vassell M. A., Fileta B. B., Kitov S., Kolodny N., Heppner D. G., Haynes J. D., Lanar D. E. Purification, characterization, and immunogenicity of the refolded ectodomain of the Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1 expressed in Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:3101–3110. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.3101-3110.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehlin C., Boni E., Buckner F. S., Engel L., Feist T., Gelb M. H., Haji L., Kim D., Liu C., Mueller N., et al. Heterologous expression of proteins from Plasmodium falciparum: results from 1000 genes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2006;148:144–160. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vedadi M., Lew J., Artz J., Amani M., Zhao Y., Dong A., Wasney G. A., Gao M., Hills T., Brokx S., et al. Genome-scale protein expression and structural biology of Plasmodium falciparum and related Apicomplexan organisms. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2007;151:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glover C. J., Goddard C., Felsted R. L. N-myristoylation of p60src. Identification of a myristoyl-CoA:glycylpeptide N-myristoyltransferase in rat tissues. Biochem. J. 1988;250:485–491. doi: 10.1042/bj2500485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.King M. J., Sharma R. K. N-myristoyl transferase assay using phosphocellulose paper binding. Anal. Biochem. 1991;199:149–153. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McWherter C. A., Rocque W. J., Zupec M. E., Freeman S. K., Brown D. L., Devadas B., Getman D. P., Sikorski J. A., Gordon J. I. Scanning alanine mutagenesis and de-peptidization of a Candida albicans myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase octapeptide substrate reveals three elements critical for molecular recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:11874–11880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rocque W. J., McWherter C. A., Wood D. C., Gordon J. I. A comparative analysis of the kinetic mechanism and peptide substrate specificity of human and Saccharomyces cerevisiae myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:9964–9971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Towler D. A., Eubanks S. R., Towery D. S., Adams S. P., Glaser L. Amino-terminal processing of proteins by N-myristoylation. Substrate specificity of N-myristoyl transferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:1030–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tate E. W., Bowyer P. W., Brown K. A., Smith D. F., Holder A. A., Leatherbarrow R. J. Peptide-based inhibitors of N-myristoyl transferase generated from a lipid/combinatorial peptide chimera library. Signal Transduction. 2006;6:160–166. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.