Abstract

Pontin (Pont) and Reptin (Rept) are paralogous ATPases that are evolutionarily conserved from yeast to human. They are recruited in multiprotein complexes that function in various aspects of DNA metabolism. They are essential for viability and have antagonistic roles in tissue growth, cell signalling and regulation of the tumour metastasis suppressor gene, KAI1, indicating that the balance of Pont and Rept regulates epigenetic programmes critical for development and cancer progression. Here, we describe Pont and Rept as antagonistic mediators of Drosophila Hox gene transcription, functioning with Polycomb group (PcG) and Trithorax group proteins to maintain correct patterns of expression. We show that Rept is a component of the PRC1 PcG complex, whereas Pont purifies with the Brahma complex. Furthermore, the enzymatic functions of Rept and Pont are indispensable for maintaining Hox gene expression states, highlighting the importance of these two antagonistic factors in transcriptional output.

Keywords: Trithorax group, ATPase, transcriptional regulation, epigenetics

Introduction

Pontin (Pont) and Reptin (Rept) are paralogous ATP-dependent DNA helicases recruited as part of several chromatin-modifying multiprotein complexes thought to act in epigenetic mechanisms that control various aspects of DNA metabolism, including transcription, replication and repair. They are involved in the regulation of cell-cycle progression, in growth control by Myc, in Wnt–β-catenin signalling and in neoplastic transformations (reviewed by Gallant, 2007). Furthermore, mutation of either gene confers a lethal phenotype in all species examined so far, indicating non-redundant essential functions during development.

At the mechanistic level, the roles of Pont and Rept are poorly understood. They have essential roles in the assembly of the Ino80 chromatin remodelling complex (Jónsson et al, 2004), yet are found to have opposite activities in various mechanisms of transcription control: heart growth in zebrafish (Rottbauer et al, 2002), Wnt signalling (Bauer et al, 2000) and KAI1 tumour metastasis suppressor gene expression (Kim et al, 2005), in which Pont acts as a transcriptional co-activator and Rept as a co-repressor (reviewed by Gallant, 2007).

In most cases, Pont and Rept are found together in the same multiprotein complex. Thus, the functional antagonism of either Pont or Rept occurs within the same complex, or it is achieved through distinct antagonistically acting complexes. Although the complexes containing both Pont and Rept have been well studied, there is no evidence, so far, to show that these complexes can have both active and repressive roles in the same target genes. Contrarily, in the case of KAI1 expression, Pont collaborates with Tip60 for activation and Rept with β-catenin for repression (Kim et al, 2005). Thus, it is likely that whenever Pont and Rept have opposing activities on gene expression, that these activities are through the action of distinct protein complexes.

Here, we focus on a well-studied epigenetic mechanism of transcriptional control: the maintenance of Hox gene expression by opposing actions of Polycomb group (PcG) and Trithorax group (TrxG) complexes (Ringrose & Paro, 2004). In this respect, rept has recently been described as genetically interacting with PcG genes and components of the Tip60 complex (Qi et al, 2006), in which the authors proposed a role for the Tip60 complex in gene silencing. However, given the opposing actions of Pont and Rept in transcription, Rept having been identified in PRC1 (Saurin et al, 2001) and the role of Tip60 in transcriptional activation, the proposed role of Tip60 does not address the role of the opposing partner of Rept—Pont—in the complex (Kusch et al, 2004) and the epigenetic regulation of Hox genes by PcG and TrxG proteins. Here, we show that Rept forms a component of the embryonic PRC1 PcG complex, whereas Pont co-purifies with the Brahma complex (Brm-C) TrxG complex, and also show indispensable roles for the enzymatic activities of Pont and Rept in maintaining Hox gene expression states.

Results And Discussion

Pont and Rept antagonistically contribute to Hox silencing

Rept has recently been reported to suppress variegation (Qi et al, 2006). We found that Pont behaves as an enhancer (supplementary Fig S1 online). The antagonistic effects of Pont and Rept on pericentric heterochromatin assembly provide a clear clue as to their roles in transcription as Su(Var) (Rept) is implicated in chromatin condensation, whereas E(Var) (Pont) acts to relax and open up chromatin (reviewed by Elgin, 1996).

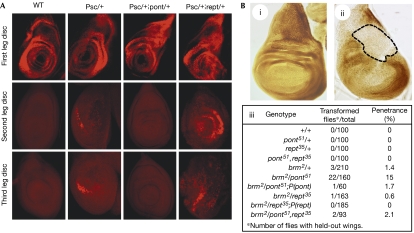

To assess the role of Pont and Rept in the maintenance of Hox gene transcription by PcG and TrxG proteins, we first tested for genetic interactions with PcG genes. Males heterozygous for pont, rept or pont and rept do not show a PcG phenotype of extra sex combs on T2 and T3 legs, whereas heterozygosity for pont or rept significantly reduces or enhances the sex comb phenotype of Psc1 (Psc for Posterior sex combs) or PcXT109 male heterozygotes (supplementary Table S1 online). These effects are specific as providing an extra copy of rept or pont in these backgrounds restores the PcG mutant phenotype. To obtain direct evidence for a role in Hox gene control, we analysed Scr (Sex combs reduced) and Ubx (Ultrabithorax) patterns in imaginal discs. Scr is expressed in T1 but not in the most-posterior wild-type leg discs, a pattern unaffected by heterozygosity for pont or rept (or pont and rept). Heterozygosity for Psc leads to Scr derepression in a few cells of T2 and T3 discs, and eliminating one copy of pont or rept in this context significantly reduces or, conversely, increases ectopic Scr accumulation (Fig 1A). Ubx is not detected in the epithelia of wild-type and pont or rept heterozygous wing discs, whereas it accumulates in some cells of Psc heterozygous discs. The additional mutation of one copy of pont or rept abolishes or exacerbates, respectively, Ubx ectopic expression (supplementary Fig S2 online). It is noteworthy that similar levels of the Hox protein are detected in Psc and triple pont, rept, Psc heterozygous discs. Thus, Pont and Rept contribute in an antagonistic manner to PcG-mediated repression of Scr and Ubx. Consistent with the opposite genetic interactions observed previously, Pont and Rept therefore behave as dominant suppressor and enhancer of PcG mutations, respectively.

Figure 1.

The mutations pont and rept interfere with PcG and trxG genes in an opposite manner to control Hox gene expression. (A) Scr immunodetection in first, second and third instar leg discs in the indicated genetic contexts. (B) Antp immunodetection in (i) wild-type and (ii) brm2/pont wing discs. The dashed area indicates Antp loss in the dorsal hinge region. (iii) Effect of pont and rept mutations on the brm2 dominant held-out wing phenotype. Antp, Antennapedia; Brm, Brahma; PcG, Polycomb group; Pont, Pontin; Psc, Posterior sex combs; Rept, Reptin; Scr, Sex combs reduced; TrxG, Trithorax group; WT, wild-type.

As the sex comb phenotype is initially determined by the PcG mutation, these data do not distinguish between PcG-specific effects and global transcriptional effects. Thus, we studied the role of Pont and Rept in Hox silencing mediated by chromosomal integrity. Homologous pairing of regulatory elements in the Scr gene is crucial for silencing, and chromosomal aberrations that disrupt this pairing lead to derepression of Scr in the second and third thoracic segments (Southworth & Kennison, 2002). Thus, we tested for genetic interactions of pont and rept with the gain-of-function allele ScrMsc (Southworth & Kennison, 2002). The number of ectopic sex comb teeth on T2 and T3 legs observed in male flies heterozygous for ScrMsc significantly decreases or increases when one copy of pont or rept, respectively, is removed. These effects are countered by pont or rept genomic transgenes, and the ScrMsc phenotype remains unchanged on simultaneous dosage reduction of both genes (supplementary Table S2 online). These results indicate that Pont acts as a co-activator and Rept as a co-repressor in the maintenance of Hox gene transcription, as do the TrxG and PcG proteins.

Pont and Rept antagonistically contribute to Hox expression

To investigate the possible roles of Pont and Rept in TrxG-dependent maintenance of Hox gene expression, we performed genetic interaction assays using the brm2 allele, which in heterozygosis results in a held-out wing phenotype at low frequency (Vazquez et al, 1999). Heterozygous pont, rept or pont and rept mutants do not induce such a phenotype alone, whereas the mutation of one copy of pont or rept significantly enhances or reduces the held-out wing phenotype of brm2/+ flies, and a balanced reduction of pont and rept in triple heterozygotes results in a phenotype of penetrance similar to that in brm2/+ flies (Fig 1Biii). Thus, pont and rept behave as dominant enhancer and suppressor, respectively, of the brm2 mutation.

As brm2 reduces the activity of the Antp P2 promoter (Antp for Antennapedia; Vazquez et al, 1999), we tested whether Pont interferes with Brm at the level of Antp transcription in wing discs. We observed that Antp, which is usually expressed at high levels in the presumptive notum, no longer accumulates in the dorsal hinge region of brm2/pont discs (Fig 1Bii)—the territory that gives rise to the adult structure connecting body wall and wing. A similar reduction of Antp accumulation was never observed in a sample of more than 50 brm2/+ wing discs, which we presume is related to the low penetrance of the held-out wing phenotype in this genotype. Thus, Pont cooperates with Brm to maintain transcription at the Antp P2 promoter, an effect that is counteracted by Rept.

These data show that Rept, acting as a co-repressor, and Pont, acting as a co-activator, participate in epigenetic mechanisms of opposite transcriptional control of Hox genes through cooperation with PcG and TrxG proteins.

Pont and Rept ATPases are essential for Hox expression states

Members of the AAA+ family of DNA helicases, Pont and Rept contain ATP-binding and hydrolysis domains, and mutating the ATPase domain leads to dominant-negative effects over wild-type bacterial, yeast and human proteins (reviewed by Erzberger & Berger, 2006). We generated transdominant Pont and Rept point mutants in the ATPase domain (PontD302N and ReptD295N) and established Gal4-UAS-based conditional expression fly lines.

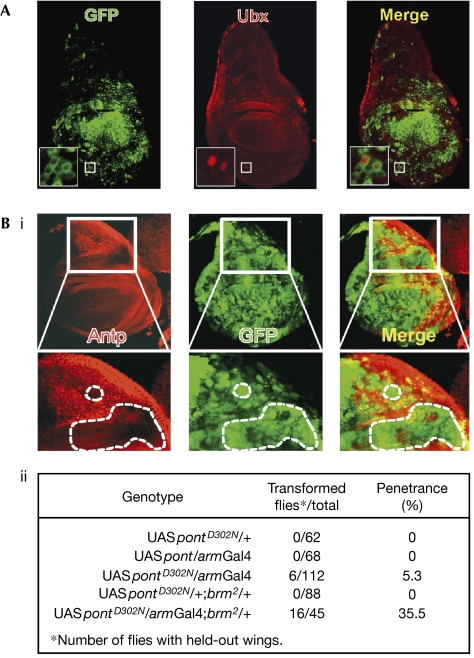

Driving ReptD295N by armGal4 (arm for armadillo) resulted in lethality at the pupal stage. However, in third instar wing discs expressing ReptD295N using armGal4, several transdominant Rept-expressing cells also ectopically expressed Ubx (Fig 2A, insets), whereas driving either wild-type Rept or PontD302N using armGal4 had no effect on Ubx (not shown). Thus, expression of ATPase-deficient Rept leads to Ubx derepression. Conversely, although expressing PontD302N by armGal4 is viable, the resulting adults showed the brm held-out wing phenotype, whereas expression of wild-type Pont did not (Fig 2Bii). The penetrance of this phenotype in armGal4/UASpontD302N adults is significantly greater than that observed in brm2 heterozygotes (compare Fig 2Bii and iii). Furthermore, expression of PontD302N by armGal4 in brm2 heterozygotes shows an even stronger penetrance (35.5%) of the wing phenotype, indicating functional cooperation between Brm and enzymatically active Pont, and a direct role for Pont in maintaining Antp transcription. Indeed, immunostained wing discs showed a marked absence of Antp in dorsal hinge cells expressing PontD302N (Fig 2Bi). Thus, eliminating Rept enzymatic activity leads to Ubx derepression and that of Pont to Antp repression. This loss of maintenance of Hox expression occurs in an otherwise wild-type background and, hence, the two paralogous proteins have clear opposing direct ATPase-dependent actions on Hox gene transcription.

Figure 2.

Pont and Rept enzymatic activities are essential for the maintenance of Hox gene expression. (A) Ubx derepression by ReptD295N. Confocal section showing GFP (left) and Ubx staining (centre) in an armGal4/UASreptD295N;UASGFP/+ wing disc. The insets focus on cells expressing ReptD295N (green) resulting in Ubx derepression (red). Note that high Ubx staining around the periphery of the disc is due to Ubx expression in the peripodial membrane. (B) (i) Antp repression by PontD302N. Stack of confocal sections showing Antp (left) and GFP (centre) expression in an armGal4/UASpontD302;UASGFP/+ wing disc. The lower panels are magnified views of the boxed areas and highlight sites of Antp repression (dashed areas). (ii) Held-out wing phenotype induced by PontD302N and genetic interactions with brm2. Antp, Antennapedia; Arm, Armadillo; Brm, Brahma; GFP, green fluorescent protein; Pont, Pontin; Rept, Reptin; Ubx, Ultrabithorax.

To better understand at what level Pont and Rept act on Hox gene regulation, we studied their effect on an mw (miniwhite) reporter gene under the control of the iab-7 PcG response element (PRE; Mishra et al, 2003). Silencing of mw by PRE was partly suppressed by mutation of either rept or the PcG gene Asx (Additional sex combs), an effect that was compounded in rept/Asx transheterozygotes (supplementary Fig S3 online). Conversely, mutation of pont resulted in increased silencing of mw by the iab-7 PRE (supplementary Fig S3 online). These data indicate that Rept and Pont have direct opposing activities on PRE-regulated gene transcription, as do the PcG and TrxG genes.

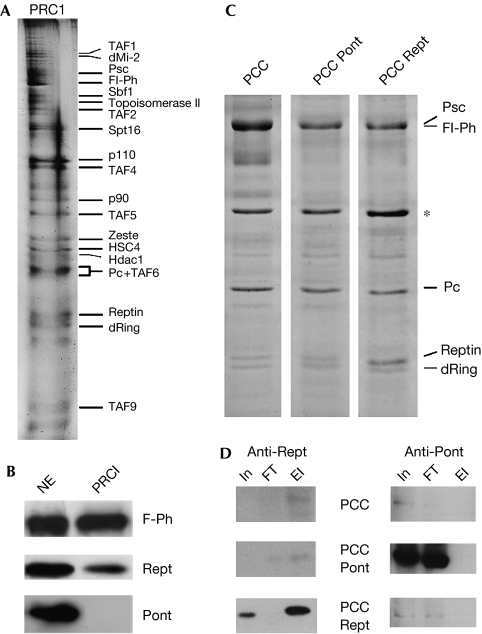

Rept forms an integral component of PcG PRC1

Rept has previously been identified by mass spectrometry in PRC1 (Saurin et al, 2001), although this was not investigated in further detail. Furthermore, it remains unknown whether Pont is also present in PRC1. To address whether PRC1 represents the first example of Rept in a purified protein complex without its paralogue, we purified PRC1 from Drosophila embryos (Fig 3A,B). Through numerous independent purifications, Rept, but not Pont, co-purified with PRC1 (Fig 3B). PRC1 comprises several proteins, of which only four are known PcG (Saurin et al, 2001). To determine whether Rept associates in PRC1 through direct interaction with PcG or with non-PcG members of PRC1, we performed complex reconstitution assays. Infection of Sf9 cells with baculoviruses encoding Flag-Polyhomeotic (F-Ph), Psc, Pc and dRing allows reconstitution of the PRC1 core complex (PCC; Francis et al, 2001). In addition, by co-infecting baculovirus encoding either Pont or Rept, we investigated whether either of these could incorporate into the reconstituted PCC.

Figure 3.

Rept is an integral component of PRC1. (A) SDS–PAGE (silver stain) of PRC1. Protein bands are labelled according to Saurin et al (2001). (B) Western analyses of PRC1. NE: 20 μg nuclear extract; PRC1: 15 μl PRC1. (C) SDS–PAGE (Coomassie blue) of reconstituted PCCs from Sf9 cells expressing Flag-Polyhomeotic (F-Ph), Psc, Pc, dRing (PCC), and Pont (PCC-Pont) or Rept (PCC-Rept). *Nonspecific Sf9 protein. (D) Western analyses of Rept (left) and Pont (right) profiles during purification of PCCs shown in (C). In: 1.5 μl (15 μg) Sf9 nuclear extract; FT: 1.5 μl anti-Flag affinity column flow through; El: 3 μl purified complex. PCC, PRC1 core complex; Pont, Pontin; Psc, Posterior sex combs; Rept, Reptin; SDS–PAGE, SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

In PCC, a Coomassie blue-stained protein migrating at the size of Rept slightly immunoreacted with antibodies to Drosophila Rept (Fig 3C,D) and might correspond to endogenous Sf9 Rept. Co-infection with PCC and Rept viruses resulted in depletion of recombinant Rept from the nuclear extract on incubation with anti-Flag matrix and strong enrichment of Rept in the purified complex (Fig 3D). Conversely, co-infection with PCC and Pont viruses resulted in neither the depletion of Pont from the nuclear extract by anti-Flag matrix nor its enrichment in the purified PCC (Fig 3D). Thus, Rept physically interacts with PRC1 PcG proteins, whereas Pont does not, placing Rept as an authentic PRC1 component.

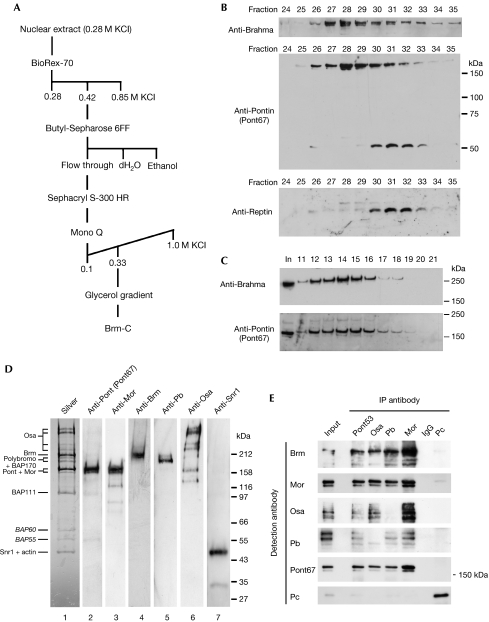

Pont associates with TrxG Brm-C

So far, Pont has not been described in any known TrxG complex. Given the genetic interactions with brm, the antagonism with Rept in Hox control and its absence in PRC1, we used column chromatography purifications to determine whether Pont associates with Brm in a TrxG complex (Fig 4A). In nuclear extracts from the embryo, two independent Pont antibodies—Pont53 (Bauer et al, 2000) and Pont67 (this study)—showed, besides the predominant 50 kDa monomeric form, a series of slowly migrating species, of which one, of 170 kDa, became highly enriched following BioRex-70 chromatography (data not shown). This 170 kDa protein is Pont and not an unrelated protein crossreacting with our antibodies as it is present in Flag-Pont purifications from Sf9 extracts, is recognized by both Pont and Flag antibodies and was positively identified by nano-ESI-IT ion trap mass spectrometry (supplementary Fig S4 online). By following the purification profiles of Brm and Pont during extract fractionation, we found that 170 kDa Pont always co-purifies with Brm (data not shown) and, at the Mono Q step, 170 kDa Pont and Brm purifies away from 50 kDa Pont and Rept (Fig 4B). Furthermore, by fractionating through a glycerol gradient, we found that Pont purifies in the same complex as Brm (Fig 4C). The Pont–Brm glycerol gradient peak, analysed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), western blot and multidimensional protein identification technology (Washburn et al, 2001), corresponds to a highly purified complex containing 13 prominent protein species, identified as Pont and all Brm-C components (Fig 4D; supplementary Table S4 online). At least two distinct Brm-C components exist in Drosophila, BAP and PBAP, which contain shared subunits and either Osa (BAP) or Pb and BAP170 (Mohrmann et al, 2004). Both Pb and Osa antibodies co-precipitated 170 kDa Pont, and Pont53 equally co-precipitated 170 kDa Pont (revealed by Pont67), Osa and Pb, as well as all members of Brm-C tested (Fig 4E), indicating that 170 kDa Pont interacts with both BAP and PBAP complexes.

Figure 4.

Pont co-purifies with the Brahma complex. (A) Purification scheme of Brm-C. (B) Western analyses of Mono Q fractions in which 50 kDa Pont and Rept purify away from the 170 kDa Pont and Brm peak. (C) Western analyses of peak fractions from glycerol gradient sedimentation of Mono Q fraction 28. (D) 4–15% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (silver staining, lane 1) and western analyses (lanes 2–7) of the Brm–Pont peak (glycerol gradient fraction 14). Note that the antibody used in lane 2 (Pont67) does not crossreact with Mor (J. Antao and R. Kingston, personal communication). (E) Western analyses of proteins precipitated from 0.42 M BioRex-70 fraction by antisera to Pont (IP, Pont53; western, Pont67), Osa, Pb, Mor, Pc or rabbit IgG. Input, 2.5 μl (10 μg); IP, 10 μl (1/10). Brm-C, Brahma complex; IP, immunoprecipitation; Pont, Pontin; Rept, Reptin.

Pont has not previously been found in Brm-C by using classical mass spectrometry of bands excised from gels (Papoulas et al, 1998; Kal et al, 2000). However, the unbiased and sensitive multidimensional protein identification technology identified all the previously known components of Brm-C together with 170 kDa Pont. This study is the first, to our knowledge, to describe a 170 kDa Pont form in Drosophila and might explain why Pont has not previously been found in Brm-C, especially because the predicted molecular weight of Pont is 50 kDa. Alternatively, it is feasible that conditions used by other groups to purify Brm-C destroyed the interaction with Pont, although our immunoprecipitation conditions show that this interaction is stable up to 600 mM salt. However, 170 kDa Pont is only barely detectable by western blotting in our nuclear extracts when compared with 50 kDa Pont, becoming enriched following initial fractionations. Thus, if Pont is associated with Brm-C (and not an integral component of it), then small changes in extract preparation could reduce or eliminate the quantity of 170 kDa Pont in the extract and thus in the complex. Nonetheless, our data show that 170 kDa Pont robustly associates with Brm-C throughout the purification scheme and also through specific immunoprecipitations with Pont or Brm-C antibodies. The nature of 170 kDa Pont is puzzling; this species could not have been generated from a longer transcript, as it is identified by Flag and Pont antisera, as well as mass spectrometry when the open reading frame complementary DNA fused to a Flag tag is expressed and purified from Sf9 cells (supplementary Fig S4 online). Given the identified molecular weights of Pont (50, 110 and 170 kDa), we believe that these higher molecular weight species are reducing/denaturing-resistant multimers of the monomeric 50 kDa protein, although the nature of this multimerization requires experimental confirmation.

The co-purification of Pont with Brm in Brm-C indicates that the genetic interaction of pont with brm in Hox control translates the functional cooperation of the two factors within Brm-C. PRC1 is believed to stabilize chromatin structure by counteracting remodelling by Brm-C (reviewed by Francis & Kingston, 2001). The finding that Rept and Pont co-purify separately in these functionally antagonistic complexes affords an explanation for their opposite effects on Hox gene transcription. Although ATP hydrolysis by Pont and Rept is essential for maintaining Hox gene transcription (Fig 2), we did not detect any activity in in vitro chromatin remodelling assays (data not shown). Thus, it seems likely that these proteins use ATP hydrolysis for some purpose other than ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling.

PcG and TrxG proteins not only regulate the expression patterns of Hox, but also those of many other genes (Ringrose & Paro, 2007 and references therein). Of particular interest is the involvement of PcG PRC1 and PRC2 in prostate cancer progression (Varambally et al, 2002; Berezovska et al, 2006). The unambiguous role of Rept in promoting prostate cancer metastasis through KAI1 repression (Kim et al, 2006) and its role in PcG repression of Hox genes (this study) converge two crucial transcriptional repression pathways. Our findings, that the enzymatic activities of Pont and Rept are indispensable for maintaining transcriptional states, highlight the importance of these two transcriptionally antagonistic factors and open up new avenues of research towards a better understanding of the mechanisms that dictate the balance of transcriptional fate during development and the progression of cancer.

Methods

Flies and manipulations. All stocks except F-Ph71-51A (R. Kingston, Boston, MA, USA), pont and rept lines (Bauer et al, 2000) were obtained from Bloomington Stock Center (Bloomington, IN, USA). Primer sequences used to generate cDNA encoding PontD302N and ReptD295N are available on request. Immunodetections were performed according to standard procedures. Antibodies to Antp (4C3) and Scr (6H4.1) were from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa, IA, USA) and those to Ubx (FP3.38) were from R. White (Cambridge, UK). Images were obtained using a Zeiss Confocal 510 Meta microscope.

Protein biochemistry. PRC1 was purified from embryos according to Shao et al (1999). PCCs, including 10 μM ZnCl2 in buffers, were purified according to Francis et al (2001).

Brm-C was purified by using a multistep fast protein liquid chromatography purification strategy and is described in detail in the supplementary information online.

Immunoprecipitations were carried out from 800 μg of 0.42 M BioRex-70 fraction used for Brm-C purification, dialysed against PBS. Following preclearing with protein A Sepharose (50 μl per reaction), 25 μl anti-Pont (Pont53), 25 μl anti-Pb, 13 μl anti-Mor, 100 μl anti-Osa (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), 25 μl anti-Pc (dN-19; Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany) or 50 μg rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, Chimie, Lyon, France) were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. Immunocomplexes, isolated by binding to protein A Sepharose (50 μl) for 30 min, were centrifuged and extensively washed: ten times in PBS, eight times in PBS-650 and twice in PBS-100. Immunocomplexes were eluted with 90 μl of 0.1 M glycine pH 2.0, neutralized by 10 μl of 1 M Tris.Cl pH 8.0 and analysed by 8% SDS–PAGE.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

supplementary information

Acknowledgments

We thank colleagues and the Bloomington Stock Center for fly lines, J. Tamkun for Brm antibodies, P. Verrijzer for antibodies to Mor, Pb and Snr1, the mass spectrometry unit of the Marseille-Nice genopole platforms in Marseille and J. Wohlschlegel for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), grants from Centre Franco-Indien pour la Promotion de la Recherche Avancée (CEFIPRA), Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC), Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (LNCC), Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), and National Institutes of Health (NIH P41 RR011823), and fellowships to S.D. from Egide and LNCC, to K.B. from ANR and to B.G. from the Ministère de la Recherche et de la Technologie (MRT) ARC.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bauer A, Chauvet S, Huber O, Usseglio F, Rothbächer U, Aragnol D, Kemler R, Pradel J (2000) Pontin52 and reptin52 function as antagonistic regulators of β-catenin signalling activity. EMBO J 19: 6121–6130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezovska OP, Glinskii AB, Yang Z, Li Z-M, Hoffman RM, Glinsky GV (2006) Essential role for activation of the polycomb-group (PcG) protein chromatin silencing pathway in metastatic prostate cancer. Cell Cycle 5: 1886–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgin SC (1996) Heterochromatin and gene regulation in Drosophila. Curr Opin Genet Dev 6: 193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erzberger JP, Berger JM (2006) Evolutionary relationships and structural mechanisms of AAA+ proteins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 35: 93–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis NJ, Kingston RE (2001) Mechanisms of transcriptional memory. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 409–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis N, Saurin AJ, Shao Z, Kingston RE (2001) Reconstitution of a functional core Polycomb repressive complex. Mol Cell 8: 545–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant P (2007) Control of transcription by Pontin and Reptin. Trends Cell Biol 17: 187–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jónsson ZO, Jha S, Wohlschlegel JA, Dutta A (2004) Rvb1p/rvb2p recruit Arp5p and assemble a functional Ino80 chromatin remodeling complex. Mol Cell 16: 465–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kal AJ, Mahmoudi T, Zak NB, Verrijzer CP (2000) The Drosophila Brahma complex is an essential coactivator for the trithorax group protein Zeste. Genes Dev 14: 1058–1071 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH et al. (2005) Transcriptional regulation of a metastasis suppressor gene by Tip60 and β-catenin complexes. Nature 434: 921–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH et al. (2006) Roles of sumoylation of a Reptin chromatin-remodelling complex in cancer metastasis. Nat Cell Biol 8: 631–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusch T, Florens L, Macdonald WH, Swanson SK, Glaser RL, Yates JRI, Abmayr SM, Washburn MP, Workman JL (2004) Acetylation by Tip60 is required for selective histone variant exchange at DNA lesions. Science 306: 2084–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra K, Chopra VS, Srinivasan A, Mishra RK (2003) Trl-GAGA directly interacts with lola like and both are part of the repressive complex of Polycomb group of genes. Mech Dev 120: 681–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrmann L, Langenberg K, Krijgsveld J, Kal AJ, Heck AJR, Verrijzer CP (2004) Differential targeting of two distinct SWI/SNF-related Drosophila chromatin remodelling complexes. Mol Cell Biol 24: 3077–3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papoulas O, Beek SJ, Moseley SL, McCallum CM, Sarte M, Shearn A, Tamkun JW (1998) The Drosophila trithorax group proteins Brm, Ash1 and Ash2 are subunits of distinct protein complexes. Development 125: 3955–3966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi D, Jin H, Lilja T, Mannervik M (2006) Drosophila Reptin and other Tip60 complex components promote generation of silent chromatin. Genetics 174: 241–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringrose L, Paro R (2004) Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and trithorax group proteins. Annu Rev Genet 38: 413–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringrose L, Paro R (2007) Polycomb/Trithorax response elements and epigenetic memory of cell identity. Development 134: 223–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottbauer W et al. (2002) Reptin and Pontin antagonistically regulate heart growth in zebrafish embryos. Cell 111: 661–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurin AJ, Shao Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Kingston RE (2001) A Drosophila Polycomb group complex includes zeste and dTAFII proteins. Nature 412: 655–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z, Raible F, Mollaaghababa R, Guyon JR, Wu CT, Bender W, Kingston RE (1999) Stabilization of chromatin structure by PRC1, a Polycomb complex. Cell 98: 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southworth JW, Kennison JA (2002) Transfection and silencing of the Scr homeotic gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 161: 733–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varambally S et al. (2002) The Polycomb group protein EZH2 is involved in progression of prostate cancer. Nature 419: 624–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez M, Moore L, Kennison JA (1999) The trithorax group gene osa encodes an arid-domain protein that genetically interacts with the brahma chromatin-remodeling factor to regulate transcription. Development 126: 733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR (2001) Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat Biotech 19: 242–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

supplementary information