Abstract

The intracellular signalling molecule cGMP regulates a variety of physiological processes, and so the ability to monitor cGMP dynamics in living cells is highly desirable. Here, we report a systematic approach to create FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer)-based cGMP indicators from two known types of cGMP-binding domains which are found in cGMP-dependent protein kinase and phosphodiesterase 5, cNMP-BD [cyclic nucleotide monophosphate-binding domain and GAF [cGMP-specific and -stimulated phosphodiesterases, Anabaena adenylate cyclases and Escherichia coli FhlA] respectively. Interestingly, only cGMP-binding domains arranged in tandem configuration as in their parent proteins were cGMP-responsive. However, the GAF-derived sensors were unable to be used to study cGMP dynamics because of slow response kinetics to cGMP. Out of 24 cGMP-responsive constructs derived from cNMP-BDs, three were selected to cover a range of cGMP affinities with an EC50 between 500 nM and 6 μM. These indicators possess excellent specifity for cGMP, fast binding kinetics and twice the dynamic range of existing cGMP sensors. The in vivo performance of these new indicators is demonstrated in living cells and validated by comparison with cGMP dynamics as measured by radioimmunoassays.

Keywords: cGMP biosensor, cGMP-dependent protein kinase (cGK), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), phosphodiesterase (PDE)

Abbreviations: CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; cGK, cGMP-dependent protein kinase; cNMP-BD, cyclic nucleotide monophosphate-binding domain of cGK; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; PDE, phosphodiesterase; GAF, cGMP-specific and -stimulated PDEs, Anabaena adenylate cyclases and Escherichia coli FhlA; GC, guanylyl cyclase; HEK-293, human embryonic kidney; RIA, radioimmunoassay; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein

INTRODUCTION

The second messenger cGMP is involved in a variety of physiological processes in mammals, especially in the nervous and vascular systems, including mediation of smooth-muscle relaxation, inhibition of platelet aggregation and modulation of synaptic plasticity [1–5].

cGMP signals elicited by hormonal stimulation in a given tissue are determined by the cGMP-generating and -degrading enzymes present. Two families of cGMP-generating enzymes exist: the peptide receptor GCs (guanylyl cyclases), which are membrane-spanning enzymes activated by peptide hormones such as the atrial natriuretic peptide, and the nitric oxide (NO) receptor GC, which is activated by the short-lived messenger NO [6–10]. On the other hand, several families of differentially regulated cGMP-degrading PDEs (phosphodiesterases) exist [11,12], e.g. PDE1 is stimulated by Ca2+, whereas PDE5 is activated by its substrate cGMP. The given combination of GCs and PDEs within specific cell types and subcellular compartments therefore critically determines amplitude and shape of cGMP signals. The cellular effects of cGMP are conveyed by cGKs (cGMP-dependent protein kinases) [13–15], cGMP-regulated ion channels [16] and by cGMP-regulated PDEs [1,12].

The biological effects of cGMP, such as in the relaxation of blood vessels, can be recorded continuously using established techniques, whereas the cGMP signals themselves cannot be monitored in this fashion. Currently, cGMP signals can only be measured from cell lysates or tissue lysates by RIA (radioimmunoassay) or ELISA, using antibodies against cGMP. Hence, a temporal resolution requires determination of tissue cGMP contents at several consecutive time points. Acquisition of time courses in this way is laborious, which is why the vast majority of cGMP values reported in the literature were obtained at a single time point, typically as late as 10 min after stimulation of cells or tissues.

However, there is a growing body of evidence which suggests that cGMP signals are of a rather fast and transient nature. Matsuzawa and Nirenberg [17] reported that N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells responded to carbamylcholine stimulation with an up to 200-fold increase in cGMP that was transient and lasted for less than 2 min. These rapid cGMP kinetics were later confirmed using membrane patches with cyclic-nucleotide-gated channels crammed into N1E cells [18]. An even faster cGMP signal was demonstrated in platelets after NO stimulation that peaked within 10 s and returned to baseline cGMP within 30 s [19,20]. Thus indicators that allow continuous monitoring of the cGMP concentration in living cells will substantially improve our knowledge of cyclic nucleotide signalling.

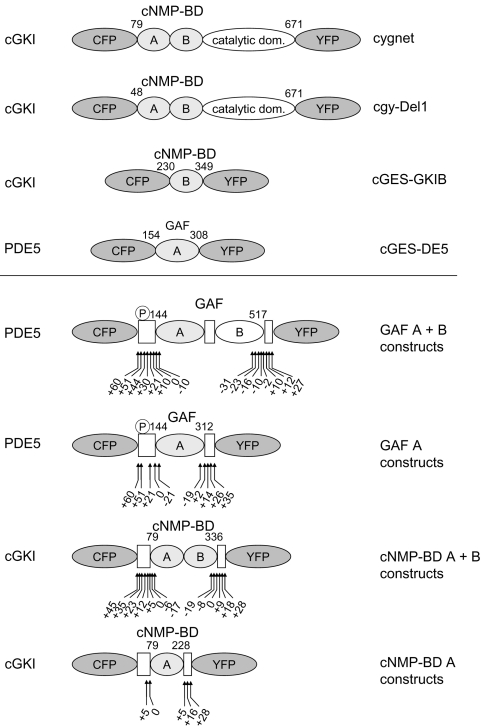

To date, three attempts have been made to develop such cGMP indicators. All contained a cGMP-binding domain sandwiched between two fluorescent proteins [21,22] (Figure 1) and took advantage of changes in FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer) between the fluorophores upon conformational changes caused by the binding of cGMP. Two different types of cGMP-binding domains have been identified. cNMP-BD (cyclic nucleotide monophosphate-binding domain of cGK) is conserved in cGKs and the cGMP-regulated ion channels [13,14]. The second binding domain, dubbed GAF (cGMP-specific and -stimulated PDEs, Anabaena adenylate cyclases and Escherichia coli FhlA domain), abbreviating the three proteins in which it was first identified, is in mammals exclusively found in PDEs [23,24]. Interestingly, cNMP-BD or GAF domains are arranged in tandem pairs in cGKs or PDEs respectively. In cGKI, the N-terminal cNMP-BD, designated cNMP-BD A, has been described as a high-affinity binding site, whereas cNMP-BD B has a rather low cGMP affinity [25,26]. In PDE5, the N-terminal GAF domain, GAF-A, binds cGMP, leading to activation of the enzyme [27,28].

Figure 1. Schematic domain structure of cGMP indicators.

All indicators are composed of a fragment of a cGMP-binding protein sandwiched between CFP and YFP. Shown are the cGMP sensors already described (upper panel) and the ones described in this manuscript (lower panel). The cGMP-binding proteins that the indicators were derived from are stated on the left; the name of the sensor is on the right. The sensors contain the cGMP-binding sites cNMP-BD (cGKI) or GAF (PDE5), either as a single site A or B or as tandem of A+B. The numbers indicate the N- and C-terminal amino acids of the cGMP-binding domain used. The first cGMP sensors, ‘cygnet’ and ‘cgy’, were derived from cGKI with only 78 or 47 N-terminal amino acids deleted. cGES-GKIB and cGES-DE5 were generated from a single cGMP-binding site of either cGKI or PDE5 respectively. The general design of the constructs characterized in this manuscript is given in the lower panel. The boxes represent the regions of the parent proteins adjoining the cGMP-binding domains. From PDE5, either the tandem GAF A+B domains or the isolated GAF A domain were used and shortened or elongated by the amino acids indicated by the arrows. The same strategy was applied to the cNMP-BD of cGKI, and a range of different constructs was created, as indicated by the arrows. The PDE5 phosphorylation site is indicated by ℗.

The first two cGMP sensors, which were described 5 years ago, used almost full-length cGKI containing both cNMP-BDs and lacking only the dimerization domain (47 or 78 amino acids) [29,30]. Recently, an attempt was made to generate simpler sensors using a single cNMP-BD from cGKI or a single GAF domain from either PDE2 or PDE5 [31] (Figure 1). The authors reported that only the PDE5 GAF construct responded at a high enough speed to allow monitoring of intracellular cGMP signals.

Taken together, only limited efforts have been made to create cGMP indicators. On one hand, complete cGKs have been used, raising the question about the purpose of the catalytic domains in the indicator. On the other hand, only single cGMP-binding domains were tested, whereas both the cGK and PDE each contain these domains in tandem.

Here, we describe a systematic approach to design cGMP indicators using the single and tandem cGMP-binding domains of cGKI (cNMP-BD) and PDE5 (GAF). More than 50 constructs containing different regions of these domains were generated and tested in vitro. On the basis of these data, three indicators containing the tandem cNMP-BD exhibiting cGMP affinities between 500 nM and 6 μM were chosen to span a range of cGMP concentrations. The in vivo performance of the new indicators is demonstrated by simultaneous measurement of cGMP signals with the new cGMP indicators and RIAs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of the sensors

DNA encoding the various cGMP-binding domains (which are listed in Tables 1 and 2) was amplified by PCR and subcloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) containing the coding region of CFP (cyan fluorescent protein) [ECFP (enhanced CFP), excised from pECFP-N1 (Clontech), equivalent to variant 10C [32], C-terminally truncated at Ala228] and YFP (yellow fluorescent protein) {EYFP (enhanced YFP), excised from pEYFP-N1 (Clontech), equivalent to variant W1B [32]}, using the type IIS restriction endonuclease Esp3I. In the resulting protein sequence, the cGMP-binding domain (Tables 1 and 2) was directly preceded by the C-terminal end of CFP (…Thr226Ala227Ala228-) and followed by YFP (-Met1Val2Ser3…) without any additional amino acids respectively. To allow screening of a large number of constructs, only some of the constructs were verified by sequencing and these showed no mutations at all.

Table 1. FRET constructs derived from the GAF domains of PDE5.

Shown are the relative changes in CFP/YFP emission ratio of the constructs derived from the PDE5 GAF domains determined in vitro as described in the Materials and methods section. The borders of the constructs containing either GAF A+B or GAF A only (see Figure 1) are stated relative to the border of the GAF domains (left column) of human PDE5a (GenBank® accession number NM_001083.2). The first and the last amino acid (aa) relative to the PDE5 holoenzyme are given in parentheses. n.d., not determined because the constructs displayed very low expression. The numbers in bold type highlight the constructs displaying FRET changes.

| Indicator construct | N-terminal elongation (first aa) | C-terminal elongation (last aa) | Change in CFP/YFP emission ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAF A+B (Asp144–Ala517) | +60 (Gln84) | +10 (Ser527) | 50 |

| +51 (Val93) | −23 (Ala494) | <5 | |

| −10 (Gln507) | <5 | ||

| −2 (Ala515) | 80 | ||

| +10 (Ser527) | 40 | ||

| +27 (Ala544) | 30 | ||

| +44 (Lys100) | −23 (Ala494) | <5 | |

| −16 (Leu501) | <5 | ||

| −10 (Gln507) | <5 | ||

| −2 (Ala515) | <5 | ||

| +10 (Ser527) | <5 | ||

| +12 (His529) | <5 | ||

| +30 (Val114) | −2 (Ala515) | <5 | |

| +10 (Ser527) | <5 | ||

| +21 (Ser123) | −2 (Ala515) | <5 | |

| +10 (Ser527) | <5 | ||

| +10 (Met134) | −31 (Arg486) | <5 | |

| −2 (Ala515) | <5 | ||

| +10 (Ser527) | <5 | ||

| 0 (Asp144) | −16 (Leu501) | 7 | |

| +12 (His529) | <5 | ||

| −10 (Glu154) | −31 (Arg486) | n.d. | |

| GAF A (Asp144–Ile312) | +60 (Gln84) | +14 (Glu326) | <5 |

| +51 (Val93) | −19 (Gly293) | <5 | |

| +2 (Leu314) | <5 | ||

| +14 (Glu326) | <5 | ||

| +35 (Leu347) | <5 | ||

| +21 (Ser123) | +2 (Leu314) | <5 | |

| +14 (Glu326) | <5 | ||

| 0 (Asp144) | +2 (Leu314) | <5 | |

| +14 (Glu326) | <5 | ||

| +26 (Ser338) | <5 | ||

| +35 (Leu347) | <5 | ||

| −21 (Val165) | +2 (Leu314) | n.d. | |

| +14 (Glu326) | <5 |

Table 2. FRET constructs derived from the cNMP-BD of cGKI.

Shown are the relative changes in CFP/YFP emission ratio of the constructs derived from the cNMP-BD of cGK determined in vitro as described in the Materials and methods section. The borders of the constructs containing either cNMP-BD A+B or cNMP-BD A only (see Figure 1) are stated relative to the border of the cNMP-BD (left column) of bovine cGKI (GenBank® accession number X16086.1 [44]). The first and the last amino acid (aa) relative to the cGKI holoenzyme are given in parentheses. Results are means±S.E.M. three or more independent experiments. n.d., not determined because no ratio change was detectable.

| Indicator construct | N-terminal elongation (first aa) | C-terminal elongation (last aa) | Change in CFP/YFP emission ratio (%) | EC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cNMP-BD A+B (Gln79–Tyr336) | +45 (Gln34) | 0 (Tyr336) | 29±3 | 1.47±0.44 | |

| +9 (Tyr345) | 27±2 | 0.64±0.19 | |||

| +35 (Gln44) | 0 (Tyr336) | 42±2 | 1.25±0.20 | ||

| +9 (Tyr345) | 45±2 | 0.23±0.04 | |||

| +23 (Pro56) | 0 (Tyr336) | 56±2 | 1.11±0.13 | ||

| +9 (Tyr345) | 55±3 | 0.27±0.02 | |||

| +12 (Glu67) | 0 (Tyr336) | 66±2 | 1.57±0.04 | ||

| +9 (Tyr345) | 55±3 | 0.50±0.06 | |||

| +5 (Phe74) | 0 (Tyr336) | 62±3 | 1.32±0.07 | ||

| +9 (Tyr345) | 69±2 | 0.33±0.04 | |||

| 0 (Gln79) | −19 (Asp317) | <5 | n.d. | ||

| −8 (Leu328) | 53±1 | 4.16±0.13 | |||

| 0 (Tyr336) | 63±1 | 2.24±0.16 | |||

| +9 (Tyr345) | 77±2 | 0.47±0.03 | cGi-500 | ||

| +18 (Asn354) | 41±5 | 0.37±0.01 | |||

| +28 (Asp364) | 23±3 | 0.24±0.02 | |||

| −6 (Thr85) | −8 (Leu328) | 58±2 | 5.64±0.40 | cGi-6000 | |

| 0 (Tyr336) | 72±2 | 3.06±0.47 | cGi-3000 | ||

| +9 (Tyr345) | 74±3 | 0.75±0.21 | |||

| −17 (Glu96) | 0 (Tyr336) | 22±3 | 0.49±0.02 | ||

| +9 (Tyr345) | 25±3 | 0.13±0.01 | |||

| cNMP-BD A (Gln79–Asn228) | +5 (Phe74) | +5 (Leu233) | <5 | n.d. | |

| 0 (Gln79) | +5 (Leu233) | <5 | n.d. | ||

| +16 (Asn244) | <5 | n.d. | |||

| +28 (Asp256) | <5 | n.d. |

In vitro characterization of the sensors

The indicators were transiently transfected into HEK-293 (human embryonic kidney) cells using Fugene6, according to the manufacturer's (Roche) instructions. Transfected cells (1×107 cells) were harvested and lysed in homogenization buffer [50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM triethanolamine/HCl, pH 7.4, containing 2 mM dithiothreitol and a 100-fold dilution of a protease-inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)] by sonication (1 pulse, 5 s). A cytosolic fraction was obtained by centrifugation at 100000 g for 30 min at 4 °C and emission spectra were recorded by excitation of the constructs at 436 nm and measurement of the emission using a Cary eclipse spectrofluorimeter (Varian). Briefly, 10–100 μl of cytosol containing the indicators was measured in a total volume of 800 μl of buffer A (25 or 50 mM triethanolamine/HCl, pH 7.4, 2 mM dithiothreitol and 10 mM MgCl2). Concentration–response curves for cGMP and cAMP were assessed by continuous recording of CFP and YFP emissions at 475 and 525 nm respectively, and calculating the emission ratio at 475 to 525 nm (results are means±S.D. of ≥ three measurements). Binding kinetics were recorded at an emission of 525 nm using an RX.2000 stopped-flow device (Applied Photophysics) connected to the spectrofluorimeter. For the dissociation measurements, binding of cGMP at the indicated concentrations was confirmed by emission ratio change. Subsequently, 8 μl of the cGMP-bound indicator was diluted with buffer A to 800 μl in order to decrease the concentration of cGMP present, and emission changes at 475 and 525 nm were recorded.

In vivo measurement of cGMP dynamics

HEK-293 cells stably expressing the NO receptor GC and PDE5 were cultured as previously described [33]. Measurements were performed at room temperature (22 °C), after replacing the cell culture medium with PBS. Cells were stimulated with 200 μM of DEA-NO [2-(N,N-diethylamino)-diazenolate-2-oxide.diethylammonium salt] (Alexis Biochemicals) and 20 μM of YC-1 [3-(5′-hydroxymethyl-2′-furyl)-1-benzylindazole] (Alexis Biochemicals) at the time points indicated and subsequently cGMP contents determined by RIA as described were [33]. For fluorescence microscopy, the cells were grown on coverslips and transfected with the indicators, as detailed above. After mounting the coverslips on to the microscope stage, cells were maintained at room temperature in PBS and stimulated as described above. Calibration was attempted using the cGMP analogues (10 μM each) 8-pCPT-cGMP [8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate], 8-Br-PET-cGMP (β-phenyl-1,N2-etheno-8-bromoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate) and Sp-8-pCPT-PET-cGMPS [8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-β-phenyl-1,N2-ethenoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate Sp-isomer] (Biolog). Dual emission fluorescence microscopy was performed on an Axiovert 200 microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a Fucal 4 system (Till Photonics) and a Dual View beam splitter (Optical Insights) for simultaneous recording of both CFP and YFP emissions. Recordings were done at an excitation of 436 nm, an integration time of 2 s and using a 10× objective. Data were analysed using the NIH (National Institutes of Health) ImageJ program. Each field of view contained approx. 20 cells, and to circumvent an observer bias due to manual selection of regions of interest, all pixels exhibiting in the first captured frame >20% of the fluorescence of average bright cells were used for analysis. For each pixel, the CFP/YFP emission ratio was calculated. Mean CFP and YFP intensities and the mean CFP/YFP emission ratio of the viewing field were calculated from all pixels selected as described above and subsequently normalized to the initial baseline values. Estimation of the intracellular cGMP concentration was performed by fitting the in vitro concentration–response curves with a four parameter logistic function. Subsequently, the obtained EC50 and Hill constant were applied, together with the maximum and minimum FRET values obtained in vivo, to the inverse four-parameter logistic function to yield the intracellular cGMP concentration.

RESULTS

To generate genetically encoded indicators for cGMP measurements in living cells, different cGMP-binding domains were sandwiched between two fluorescent proteins, CFP and YFP.

PDE5-derived constructs are too slow for detection of cGMP signals

First, we tried to design cGMP indicators from PDE5 using the single GAF A domain, as well as the tandem domains GAF A+B (Figure 1). Our attempt to select regions according to the crystal structure of the PDE2 GAF domains [34] was unsuccessful, i.e. the constructs did not show cGMP-induced FRET changes. This may be due to the small number of conserved amino acids between the GAF domains of PDE2 and PDE5, resulting in relatively vague GAF borders. Thus we elongated or shortened either the GAF A domain or the combined GAF A+B domains repetitively by approx. 10 amino acids at their N- and C-termini (Table 1). These constructs were expressed in HEK-293 cells and characterized in vitro, i.e. the change in the CFP/YFP emission ratio upon addition of cGMP was recorded in cytosolic fractions (Table 1). Interestingly, as many as 51 amino acids had to be added N-terminally to the combined GAF A+B domain of PDE5 to create a functional, cGMP-responsive construct. This construct responded with an 80% increase in the CFP/YFP emission ratio on addition of 100 μM cGMP. Further elongation at either end of the construct decreased the cGMP-induced fractional change. Any deletion at the C-terminus abolished cGMP-induced FRET changes. None of the constructs containing only a single GAF A responded to cGMP with a FRET change.

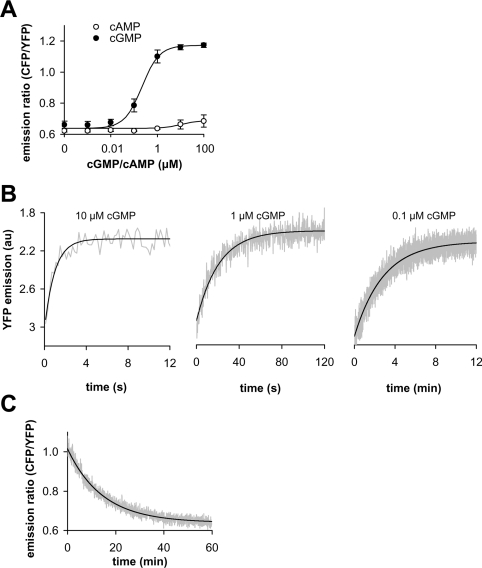

Therefore the PDE5-GAF A+B construct which had been N-terminally elongated by 51 amino acids and C-terminally shortened by two amino acids (Table 1) was further characterized. First, concentration–response curves of the construct were obtained, yielding an apparent EC50 of 0.3 μM cGMP (Figure 2A). The construct was selective for cGMP, as up to 100 μM of cAMP did not elicit a change in the response as measured by FRET (Figure 2A). However, when recording the cGMP concentration–response curves, we realized that the construct responded rather slowly to low concentrations of cGMP. Thus the kinetics of cGMP binding were assessed (Figure 2B). Although binding at 10 μM cGMP occurred with a half-life of 0.7 s, 10- and 100-fold lower concentrations yielded half-lives of 14 s and 120 s, as also predicted by the law of mass action. Slow binding at low cGMP concentrations does not necessarily render the constructs inadequate for in vivo measurements; however, fast dissociation of cGMP is essential. To assess the dissociation kinetics, the construct was incubated with 1 μM cGMP initally and then the free cGMP concentration was reduced by a 100-fold dilution, and FRET changes were recorded (Figure 2C). Under these conditions, complete reversal of the signal required 1 h, with a calculated half-life of approx. 10 min. A similar dissociation half-life can be calculated from the binding experiments. In summary, we were unable to create a functional cGMP sensor from the single PDE5 GAF A domain, and the combined GAF A+B domains of PDE5 yielded a sensor with pronounced cGMP-induced FRET changes, but intolerably slow binding and dissociation kinetics.

Figure 2. Ligand-binding characteristics of a cGMP-sensitive construct designed from the tandem domains of PDE5 GAF A+B.

(A) Concentration–response curves of PDE5-GAF A+B (N-terminally elongated by 51 amino acids and C-terminally shortened by two amino acids) for cGMP and cAMP were determined in vitro from the change in emission ratio at 475 nm (CFP emission) to 525 nm (YFP emission). (B) Binding kinetics at 0.1–10 μM cGMP were recorded using a rapid-mixing device at 525 nm (YFP) (note the different time scales). Original trace data (grey lines) were fitted to single exponential kinetics (black lines) and yielded half-lives of approx. 0.7, 14, and 120 s at 10, 1 and 0.1 μM cGMP respectively. (C) Dissociation of cGMP was assessed as a change in the emission ratio after a 100-fold dilution following binding of 1 μM cGMP. Original trace data (grey) were fitted to single exponential kinetics (black); the half-life was approx. 10 min.

cGMP indicators derived from cGK display fast kinetics

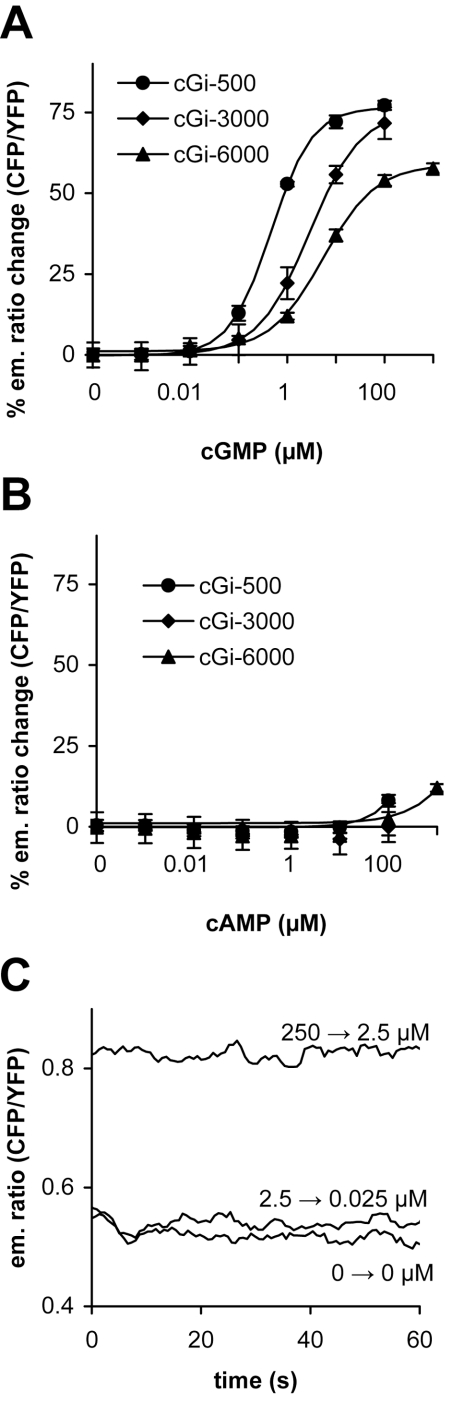

Next, we re-evaluated the already existing cGMP sensors containing almost full-length cGKI [30] and found much faster binding kinetics than with the GAF constructs in vitro (results not shown). It was then decided to construct new cGMP indicators from the cNMP-BD of cGKI. The margins of the cNMP-BD were deduced from the cAMP-binding domains of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase, which was crystallized 10 years ago [35]. To circumvent extremely low cGMP affinities, we used the high-affinity cGKI cNMP-BD A [25,26] and the tandem of cNMP-BD A+B to generate the indicators (Figure 1). As described for the GAF domains of PDE5, we screened for cGMP-induced FRET changes and characterized functional, cGMP-responsive constructs with regards to cGMP affinity (Table 2). As with the GAF domains, the single cNMP-BD A did not produce functional indicators. However, constructs composed of cNMP-BD A+B responded to cGMP, with an up to 80% increase in the CFP/YFP emission ratio. On the basis of the affinity of the indicators to cGMP and the extent of the FRET response, three cGMP indicators were selected which covered a range of half-maximally effective cGMP concentrations of 500 nM, 3 μM and 6 μM, and were named cGi-500, cGi-3000 and cGi-6000 respectively (Figure 3A). cGi-500 and cGi-3000 both responded with pronounced changes in FRET (77% and 72% increase respectively), whereas cGi-6000 had a somewhat lower dynamic range of 57%. The constructs were highly selective for cGMP, as up to 1 mM cAMP elicited only marginal increases in the emission ratio (Figure 3B). Next, we assessed the binding and dissociation kinetics of the cGMP indicators. Using stopped-flow instrumentation with a dead time of 80 ms, we were unable to monitor the binding kinetics of cGMP to the new indicator constructs, i.e. binding was complete within the dead time of the instrument (results not shown). As with the GAF constructs, dissociation was characterized using a 100-fold dilution of the cGMP-bound indicators. In contrast to the GAF construct (Figure 2C), dissociation was complete within the mixing time (Figure 3C), clearly showing that these cGMP indicators are fast enough to monitor intracellular cGMP signals.

Figure 3. Properties of the cGMP indicators cGi-500, -3000 and -6000.

cGMP (A) and cAMP (B) affinities of the indicators cGi-500 (●), -3000 (◆) and -6000 (▲) were determined in vitro from the change in CFP to YFP emission ratio. The ratio changes were normalized to the initial value determined in the absence of cGMP. (C) Dissociation of cGMP from cGi-500 was recorded after a 100-fold dilution to lower the cGMP concentration and was complete within the mixing time when cGMP was lowered from 2.5 to 0.025 μM (2.5→0.025 μM). As controls, the cGMP concentration was lowered from 250 to 2.5 μM (250→2.5 μM), leaving the indicator nearly saturated (compared with panel A), and a 100-fold dilution was performed in the absence of cGMP (0→0 μM).

The new cGMP indicators detect cGMP signals in vivo

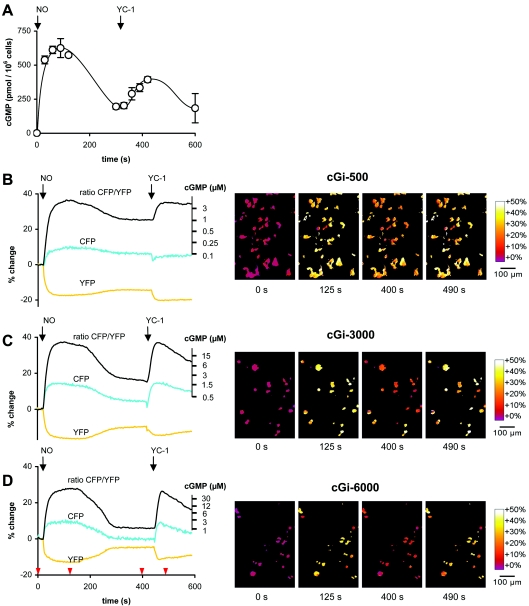

HEK-293 cells stably expressing NO-sensitive GC and PDE5 [33] were used to demonstrate the in vivo performance of the new cGMP indicators. These cells show transient cGMP increases (up to 300-fold) upon NO application that are reversible within 5 min, as demonstrated by cGMP measurements in RIAs (Figure 4A). The cGMP signals in these cells are reminiscent of those in platelets and smooth-muscle cells, which also show several-ten-fold increases in cGMP, which rapidly return to almost basal levels within seconds to minutes [19]. Since sustained activation of PDE5 outlasts the cGMP signals by far, the cells cannot be restimulated with NO. However, YC-1, a combined GC activator and PDE inhibitor [36,37], can overcome the activation of PDE5 and again increase the level of cGMP within the cell (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. cGMP signals in living cells.

cGMP signals in HEK-293 cells stably expressing the NO receptor GC and PDE5 were elicited by NO and YC-1 stimulation (indicated by arrows) and recorded by (A) RIA and fluorescence microscopy using the cGMP indicators (B) cGi-500, (C) cGi-3000 and (D) cGi-6000. (B) and (D) show the simultaneously registered mean CFP and YFP emissions (cyan and yellow respectively) and the mean CFP/YFP emission ratio (black) of the viewing field depicted in the right panel, each normalized to the baseline emission before application of NO (see the Materials and methods section). The second ordinate details the intracellular cGMP concentrations, which were calibrated as described previously (see the Materials and methods section for further information). Representative ratiometric images underlying the black CFP/YFP emission ratio curves at the time points indicated by red arrowheads are shown on the right.

These cells were transfected with the new cGMP indicators (cGi-500, cGi-3000 and cGi-6000) and FRET changes were recorded by fluorescence microscopy of live cells. The three indicators mirrored the transient cGMP elevations elicited by NO and YC-1; the NO-induced cGMP elevation immediately produced a sharp increase in the CFP/YFP emission ratio, which reached a plateau after 30–40 s and remained constant during the next 3 min, suggesting full saturation of the indicators [Figures 4B–D and Supplementary Video 1 (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/407/bj4070069add.htm)]. The cGMP levels subsequently declined (Figure 4A) and the indicators followed that decline according to their cGMP affinities, i.e. the most sensitive indicator, cGi-500, displayed a minor decrease in emission ratio, whereas the indicator with the lowest affinity, cGi-6000, decreased to almost basal level (Figures 4B and 4D). The subsequent cGMP elevation elicited by YC-1 (Figure 4A) is reflected by the three indicators and again saturation occurs for cGi-500 and -3000.

In order to calibrate the obtained FRET signals against cGMP concentrations, we considered using membrane-permeable cGMP analogues. We first ensured that the cGMP analogues bind to cGi-500, cGi-3000 and cGi-6000 and generate FRET changes comparable with cGMP by in vitro analysis (results not shown). We subsequently applied the cGK activators to the HEK-293 cell line and recorded the CFP/YFP emission ratio using the method described above for 5 min, followed by NO administration as a positive control. Unfortunately, none of the membrane-permeable cGMP analogues tested (8-pCCPT-cGMP, 8-Br-PET-cGMP and Sp-8-pCCPT-cGMPS) elicited any FRET response, whereas the control NO application produced the same signals as described above.

Although calibration was therefore impossible, an estimation of the intracellular cGMP concentration was feasible, as the extent of FRET change and the oblate peaks observed with the three indicators are indicative of cGMP-free indicators before application of NO and full saturation at the peak cGMP concentrations after NO stimulation respectively. On the basis of the cGMP concentration–response curves determined in vitro (Figure 3A), the intracellular cGMP concentrations underlying the FRET responses were calculated and depicted as the second ordinate (Figures 4B–D). The resting and peak intracellular cGMP concentrations cannot be deduced from these axes because they fall into the horizontal parts of the sigmoid standard curve. However, the cGMP concentration of the plateau after the peak elicited by NO (300–400s) is 1–2 μM, as measured with the three indicators (compare Figures 4B–D).

In summary, the congruence of the cGMP signals as determined by RIA and fluorescence microscopy clearly demonstrates the in vivo applicability of the indicators developed in the present study. Quantification of intracellular cGMP concentrations is only possible if the cGMP concentration can be brought to a level that leads to saturation of the indicators.

DISCUSSION

Conventional analysis of cGMP signalling requires disruption of the cells or tissues and subsequent detection of cGMP, e.g. by RIA. Although a moderate temporal resolution can be achieved, spatial resolution is lost by integration of the signal over many cells. These limitations initiated the development of fluorescent indicators for real time measurement of cGMP in living cells.

For this purpose, cGMP-binding domains were sandwiched between two fluorescent proteins (Figure 1). Two substantially different cGMP-binding domains are known to exist at present. The first one, cNMP-BD, is conserved in the cGKs and the cGMP-regulated ion channels. The second one, GAF, in mammals found in PDEs.

Because earlier indicators derived from the cGKI apparently had a low temporal resdution [30], we first tried to use GAF domains for development of cGMP indicators. The GAF domains of PDE5 were selected because, among the PDE GAF domains, they showed the highest specificity for cGMP in comparison with cAMP. We generated a series of constructs from the single GAF A domain, but none of these constructs showed cGMP-induced FRET changes. Furthermore, a range of constructs containing the tandem of the GAF A+B domains were characterized. Interestingly, solely constructs containing not only the two GAF domains, but also the PDE5 phosphorylation site located 42 amino acids N-terminally of the GAF domains showed cGMP-induced conformational changes. The requirement for the phosphorylation site for function is not obvious; together with biochemical data from the holoenzyme, these findings suggest that the phosphorylation site is in close proximity to the GAF domains and released on binding of cGMP [28]. Disappointingly, the conformational changes of these GAF-derived constructs were rather slow. In the presence of 100 nM cGMP, completion of the FRET change induced by cGMP binding took more than a minute. More than an hour was required for dissociation of cGMP. Such slow kinetics renders the constructs inappropriate for monitoring intracellular cGMP signals that are much faster.

Therefore we decided to create constructs from the other type of cGMP binding domains, the NMP-BD of cGKI. Similar to the tandem GAF domains present in PDEs, cGKI contains two cNMP-BDs in the N-terminal regulatory region. Besides these two cNMP-BDs, the already published cGKI indicators also contained the C-terminal kinase catalyic region as only either N- or C-terminal deletions were performed and the tested C-terminal truncations were reported to cause irreversible FRET changes on binding of cGMP [30]. By simultaneous N- and C-terminal truncations, indicators were generated containing the cNMP-BD only. As with the GAF domains, a tandem of two cGMP-BDs was required to produce a functional indicator (Table 2). Further elongation and shortening of the cGKI-based construct produced a range of functional indicators differing in the dynamic range and affinity for cGMP. To cover a spectrum of cGMP affinities, three cGMP indicators were selected and named according to their EC50: cGi-500, -3000 and -6000. These indicators exhibited fast binding and dissociation kinetics, an excellent selectivity for cGMP when compared with cAMP and a 2-fold greater dynamic range than previously described cGMP sensors (Table 3).

Table 3. Dynamic range and affinity of cGMP sensors.

Dynamic ranges and affinities (EC50) of all cGMP sensors described so far and reported in this manuscript are shown. To facilitate comparison, either the YFP/CFP (Y/C) or the CFP/YFP (C/Y) emission ratio changes are listed, whichever is larger for a given sensor, i.e. YFP/CFP is given for constructs that show cGMP-induced FRET increases and CFP/YFP for constructs showing cGMP-induced FRET decreases. n.d., value missing in the reference cited.

| cGMP effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent protein | Sensor | FRET change (%) | EC50 (μM) | Reference |

| cGK | cgy-Del1 | 24Y/C | n.d. | [29] |

| cygnet | 40C/Y | 1.9 | [30] | |

| cGES-GKIB | n.d. | 5 | [31] | |

| cGi-500 | 77C/Y | 0.5 | − | |

| cGi-3000 | 72C/Y | 3 | − | |

| cGi-6000 | 58C/Y | 6 | − | |

| PDE5 | cGES-DE5 | 16Y/C | 1.5 | [31]* |

*, Supplement.

Both cNMP-BDs were required to produce cGMP-responsive constructs. In the cGK holoenzyme, both sites have been shown to bind cGMP. Whereas the sites have different affinities and exhibit co-operativity in cGKIα, the matter is controversial for cGKIβ [38,39]. The N-terminal parts preceding the cNMP-BD are the only regions which differ between cGKIα and β, and have been shown to be responsible for the different cGMP binding properties of these two proteins [39,40]. Furthermore, proteolytic removal of amino acids preceding Gln79 in cGKIα has been demonstrated to eliminate co-operativity between the binding sites [41]. As the new cGMP indicators do not contain this N-terminal region, non-co-operative binding would be predicted to occur. Indeed, the concentration–response curves of the indicators displayed Hill coefficients of ≤1, which argues against co-operativity of cGMP binding. On the basis of available data from the cGK holoenzyme, the new indicator constructs can be assumed to bind two molecules of cGMP each. Whether the two sites have similar affinities or the conformational change is caused by occupation of the low-affinity site cannot be decided on the basis of our data indicators.

The in vivo applicability of the new indicators is demonstrated by performing fluorescence microscopy measurements in a well-characterized cellular system. As most of the cultured cell lines contain no or very little NO-sensitive GC, we used a HEK-293 cell line that stably expresses the NO receptor GC and PDE5 and shows transient cGMP signals comparable with those in platelets and smooth-muscle cells. As shown in RIAs, the cell line responds to NO stimulation with a steeps more than 100-fold increase in cGMP that is reversed within 5 min. The three new indicator constructs detected the cGMP increase immediately, and reached a plateau at the highest cGMP level. The following decline in cGMP was reflected differently by the indicators according to their cGMP sensitivity.

Since the indicators reached a plateau, they may be suspected to be too sensitive. However, maximally activating NO concentrations had to be used in order to elicit increases in cGMP which could be reliably detected by RIA. In contrast, the physiological effects of NO are regularly observed without cGMP elevations detectable by RIA [42,43]. Determination of those minute cGMP elevations requires the development of very sensitive indicators. Also, as the affinity of cGi-500 equals the one of the most important cGMP effector molecule, cGK, it permits detection of cGMP elevations relevant to activation of cGMP effector molecules. The indicators described here display a Hill slope of 1 and therefore can detect cGMP increases of 1–1.5 orders of magnitude with sufficient resolution. If the indicators are able to monitor physiologically relevant cGMP levels, leading to activation of cGK, they inevitably cannot resolve the peak cGMP concentrations elicited by maximally activating NO concentrations, which are required to produce cGMP signals that can be detected by RIA.

Standardization of FRET signals obtained with bio-indicators to the underlying biological signals is usually performed by internal calibration [22]. To do this, the intracellular concentration of the biomolecule to be measured has to be clamped to low and high concentrations and, together with the EC50 of the indicator obtained in in vitro experiments, the intracellular concentration of the biomolecule can be calculated. For Ca2+ indicators, this type of calibration is performed using chelators and ionophores; however, similar tools for the manipulation of cyclic nucleotide levels inside cells are not available. The use of activators and inhibitors of cGK, i.e. agonists and antagonists of the cNMP-BD, appeared to be the only way to force the cGMP indicators into the cGMP-bound and -free states. We tested several membrane-permeable analogues, but apparently the intracellular concentrations reached were not sufficient to elicit FRET responses. Physiological responses to these membrane-permeable activators are well established. Therefore this result was unexpected but can be explained by the fact that physiological responses already occur at low intracellular concentrations of cGMP, leading to activation of only some cGK molecules, whereas a substantial portion of the FRET indicator molecules have to become bound in order to produce a detectable FRET signal.

FRET-based indicators for intracellular cGMP have been constructed previously. The ‘cygnet’ [30] and ‘cgy’ [29] sensors, described 5 years ago, contained almost the complete cGK, which positioned the fluorophores further apart, resulting in smaller FRET changes when compared with the indicators described here (Figure 1 and Table 3). It remains unclear why deletion of the kinase catalytic domain was described to cause irreversible FRET changes upon cGMP binding [30], as this was not the case in our hands. Recently, a sensor (cGES-DE5) consisting of the GAF A domain of PDE5 was reported to have superior detection properties compared with the cygnet sensors [31]. Although our GAF A constructs differ by less than 10 amino acids from the cGES-DE5, they showed negligible cGMP-induced FRET changes. Furthermore, our functional constructs containing the tandem GAF A+B domains of PDE5 had rather slow kinetics. The reasons for these discrepancies are unknown and may be attributed to the differences between the constructs. However, the described fluorescence emission spectra of cGES-DE5 (Supplement to [31]) indicate only a 20% change in the uncorrected emission ratio in response to cGMP (Table 3).

In a systematic approach, the two known types of cGMP-binding domains were tested for their suitability to be used as cGMP indicators by fusing different fragments of the domains to two fluorescent proteins. Constructs containing the GAF domains of PDE5 exhibited extremely slow binding and dissociation kinetics. Three cGMP indicators based on the tandem of cNMP-BD A+B of cGK were generated. These responded quickly and reversibly to cGMP, displayed a high specificity for cGMP over cAMP and covered a range of cGMP affinities of between 500 nM and 6 μM. With the help of these indicators, physiologically relevant cGMP signals that remain undetectable using current techniques will be unveiled, as will be cGMP signals in subcellular-confined signalling microdomains.

Multimedia

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs Ulla Krabbe, Mrs Erika Mannheim and Mr Arkadius Pacha for technical assistance, and Professor Dr Michael Schaefer, Institut für Pharmakologie, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Campus Benjamin Franklin, Thielallee 71, 14195 Berlin, Germany for technical advice. This work was supported by grants from the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; Ko1157) and the KOFFER (Kommission für Finanzautonomie und Ergänzungsmittel of the Medical Faculty).

References

- 1.Rybalkin S. D., Yan C., Bornfeldt K. E., Beavo J. A. Cyclic GMP phosphodiesterases and regulation of smooth muscle function. Circ. Res. 2003;93:280–291. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000087541.15600.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feil R., Lohmann S. M., de Jonge H., Walter U., Hofmann F. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases and the cardiovascular system: insights from genetically modified mice. Circ. Res. 2003;93:907–916. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000100390.68771.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Münzel T., Feil R., Mulsch A., Lohmann S. M., Hofmann F., Walter U. Physiology and pathophysiology of vascular signaling controlled by guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Circulation. 2003;108:2172–2183. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000094403.78467.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garthwaite J., Boulton C. L. Nitric oxide signaling in the central nervous system. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1995;57:683–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lev-Ram V., Jiang T., Wood J., Lawrence D. S., Tsien R. Y. Synergies and coincidence requirements between NO, cGMP, and Ca2+ in the induction of cerebellar long-term depression. Neuron. 1997;18:1025–1038. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhn M. Cardiac and intestinal natriuretic peptides: insights from genetically modified mice. Peptides. 2005;26:1078–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucas K. A., Pitari G. M., Kazerounian S., Ruiz-Stewart I., Park J., Schulz S., Chepenik K. P., Waldman S. A. Guanylyl cyclases and signaling by cyclic GMP. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000;52:375–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wedel B., Garbers D. The guanylyl cyclase family at Y2K. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2001;63:215–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friebe A., Koesling D. Regulation of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase. Circ. Res. 2003;93:96–105. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000082524.34487.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobbs A. J. Soluble guanylate cyclase: an old therapeutic target re-visited. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;136:637–640. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bender A. T., Beavo J. A. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:488–520. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis S. H., Turko I. V., Corbin J. D. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: relating structure and function. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2001;65:1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)65001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeifer A., Ruth P., Dostmann W., Sausbier M., Klatt P., Hofmann F. Structure and function of cGMP-dependent protein kinases. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;135:105–149. doi: 10.1007/BFb0033671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francis S. H., Corbin J. D. Cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases: intracellular receptors for cAMP and cGMP action. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1999;36:275–328. doi: 10.1080/10408369991239213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eigenthaler M., Lohmann S. M., Walter U., Pilz R. B. Signal transduction by cGMP-dependent protein kinases and their emerging roles in the regulation of cell adhesion and gene expression. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;135:173–209. doi: 10.1007/BFb0033673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biel M., Zong X., Ludwig A., Sautter A., Hofmann F. Structure and function of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;135:151–171. doi: 10.1007/BFb0033672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuzawa H., Nirenberg M. Receptor-mediated shifts in cGMP and cAMP levels in neuroblastoma cells. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1975;72:3472–3476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trivedi B., Kramer R. H. Real-time patch-cram detection of intracellular cGMP reveals long-term suppression of responses to NO and muscarinic agonists. Neuron. 1998;21:895–906. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullershausen F., Russwurm M., Thompson W. J., Liu L., Koesling D., Friebe A. Rapid nitric oxide-induced desensitization of the cGMP response is caused by increased activity of phosphodiesterase type 5 paralleled by phosphorylation of the enzyme. J. Cell. Biol. 2001;155:271–278. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mo E., Amin H., Bianco I. H., Garthwaite J. Kinetics of a cellular nitric oxide/cGMP/phosphodiesterase-5 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:26149–26158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J., Campbell R. E., Ting A. Y., Tsien R. Y. Creating new fluorescent probes for cell biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;3:906–918. doi: 10.1038/nrm976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyawaki A., Tsien R. Y. Monitoring protein conformations and interactions by fluorescence resonance energy transfer between mutants of green fluorescent protein. Methods Enzymol. 2000;327:472–500. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)27297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aravind L., Ponting C. P. The GAF domain: an evolutionary link between diverse phototransducing proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997;22:458–459. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez S. E., Beavo J. A., Hol W. G. gaf domains: two-billion-year-old molecular switches that bind cyclic nucleotides. Mol. Interv. 2002;2:317–323. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.5.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reed R. B., Sandberg M., Jahnsen T., Lohmann S. M., Francis S. H., Corbin J. D. Fast and slow cyclic nucleotide-dissociation sites in cAMP-dependent protein kinase are transposed in type Iβ cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:17570–17575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed R. B., Sandberg M., Jahnsen T., Lohmann S. M., Francis S. H., Corbin J. D. Structural order of the slow and fast intrasubunit cGMP-binding sites of type I α cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Adv. Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1997;31:205–217. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(97)80020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rybalkin S. D., Rybalkina I. G., Shimizu-Albergine M., Tang X. B., Beavo J. A. PDE5 is converted to an activated state upon cGMP binding to the GAF A domain. EMBO J. 2003;22:469–478. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zoraghi R., Bessay E. P., Corbin J. D., Francis S. H. Structural and functional features in human PDE5A1 regulatory domain that provide for allosteric cGMP binding, dimerization, and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:12051–12063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato M., Hida N., Ozawa T., Umezawa Y. Fluorescent indicators for cyclic GMP based on cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase Iα and green fluorescent proteins. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:5918–5924. doi: 10.1021/ac0006167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honda A., Adams S. R., Sawyer C. L., Lev-Ram V., Tsien R. Y., Dostmann W. R. Spatiotemporal dynamics of guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate revealed by a genetically encoded, fluorescent indicator. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:2437–2442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051631298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikolaev V. O., Gambaryan S., Lohse M. J. Fluorescent sensors for rapid monitoring of intracellular cGMP. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:23–25. doi: 10.1038/nmeth816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsien R. Y. The green fluorescent protein. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullershausen F., Russwurm M., Koesling D., Friebe A. In vivo reconstitution of the negative feedback in nitric oxide/cGMP signaling: role of phosphodiesterase type 5 phosphorylation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:4023–4030. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez S. E., Wu A. Y., Glavas N. A., Tang X. B., Turley S., Hol W. G., Beavo J. A. The two GAF domains in phosphodiesterase 2A have distinct roles in dimerization and in cGMP binding. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:13260–13265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192374899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su Y., Dostmann W. R., Herberg F. W., Durick K., Xuong N. H., Ten Eyck L., Taylor S. S., Varughese K. I. Regulatory subunit of protein kinase A: structure of deletion mutant with cAMP binding domains. Science. 1995;269:807–813. doi: 10.1126/science.7638597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friebe A., Mullershausen F., Smolenski A., Walter U., Schultz G., Koesling D. YC-1 potentiates nitric oxide- and carbon monoxide-induced cyclic GMP effects in human platelets. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;54:962–967. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.6.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galle J., Zabel U., Hubner U., Hatzelmann A., Wagner B., Wanner C., Schmidt H. H. Effects of the soluble guanylyl cyclase activator, YC-1, on vascular tone, cyclic GMP levels and phosphodiesterase activity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:195–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolfe L., Corbin J. D., Francis S. H. Characterization of a novel isozyme of cGMP-dependent protein kinase from bovine aorta. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:7734–7741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruth P., Landgraf W., Keilbach A., May B., Egleme C., Hofmann F. The activation of expressed cGMP-dependent protein kinase isozymes I α and I β is determined by the different amino-termini. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991;202:1339–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruth P., Pfeifer A., Kamm S., Klatt P., Dostmann W. R., Hofmann F. Identification of the amino acid sequences responsible for high affinity activation of cGMP kinase Iα. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:10522–10528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heil W. G., Landgraf W., Hofmann F. A catalytically active fragment of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Occupation of its cGMP-binding sites does not affect its phosphotransferase activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 1987;168:117–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mullershausen F., Lange A., Mergia E., Friebe A., Koesling D. Desensitization of NO/cGMP signaling in smooth muscle: blood vessels versus airways. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;69:1969–1974. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.020909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mergia E., Friebe A., Dangel O., Russwurm M., Koesling D. Spare guanylyl cyclase NO receptors ensure high NO sensitivity in the vascular system. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1731–1737. doi: 10.1172/JCI27657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wernet W., Flockerzi V., Hofmann F. The cDNA of the two isoforms of bovine cGMP-dependent protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 1989;251:191–196. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81453-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.