Abstract

Yeastolate is effective in promoting growth of insect cell and enhancing production of recombinant protein, thus it is a key component in formulating serum-free medium for insect cell culture. However, yeastolate is a complex mixture and identification of the constituents responsible for cell growth promotion has not yet been achieved. This study used sequential ethanol precipitation to fractionate yeastolate ultrafiltrate (YUF) into six fractions (F1–F6). Fractions were characterized and evaluated for their growth promoting activities. Fraction F1 was obtained by 65% ethanol precipitation. When supplemented to IPL-41 medium at a concentration of 1 g L−1, fraction F1 showed 71% Sf-9 cell growth improvement and 22% β-galactosidase production enhancement over YUF (at 1 g L−1 in IPL-41 medium). However, the superiority of F1 over YUF on promoting cell growth gradually diminished as its concentration in IPL-41 medium increased. At 4 g L−1, the relative activity of F1 was 93% whereas YUF was 100% at the same concentration. At 1 g L−1, four other fractions (F2–F5) precipitated with higher ethanol concentrations and F6, the final supernatant, showed growth promoting activities ranging from 32 to 80% as compared to YUF (100%). Interestingly, a synergistic effect on promoting cell growth was observed when F6 was supplemented in IPL-41 medium in presence of high concentrations of F1 (>3 g L−1). The results suggest that ethanol precipitation was a practical method to fractionate growth-promoting components from YUF, but more than one components contributed to the optimum growth of Sf-9 cells. Further fractionation, isolation and identification of individual active components would be needed to better understand the role of these components on the cell metabolism.

Keywords: Insect cell, Yeastolate, Serum-free medium

Introduction

Insect cells used in conjunction with the baculovirus expression vector system (BEVS) are widely used as an industrially useful platform for recombinant protein production. For many years, insect cell culture was performed in basal media such as Grace’s medium supplemented with 5% or 10% serum. Serum-supplemented media have many drawbacks, such as: variability of serum lots, potential contamination with infectious agents, interference in product recovery and high cost. There have been tremendous efforts to develop serum-free media to meet industrial and research needs.

Serum elimination in insect cell culture media is largely achieved by supplementing lipid emulsion and protein hydrolysates (Maiorella et al. 1988) such as proteose peptone (Hasegawa et al. 1988), Primatone RL (Schlaeger 1996) and yeastolate (Ikonomou 2001). Among these, yeastolate has been traditionally used as a vital component and shown as the most effective for promoting growth of insect cell and enhancing production of recombinant protein (Ikonomou 2001).

Yeastolate is a highly filterable, aqueous extract of baker’s or brewer’s yeast through autolysis (Kelly 1983; Peptone Technical Manual 2002). Yeastolate has been commonly used as a key medium component for microbial fermentations for many decades (Bridson and Brecker 1970). The activity of yeastolate varies from lot-to-lot due to less controlled fermentation conditions and downstream processes (Zhang et al. 2003). Lots from the same manufacturing process could vary by almost 50% in biomass and growth promoting activity (Potvin et al. 1997). Thus, extensive “use testing” of several lots is required to identify a few lots that promote cell growth (Zhang et al. 2003). Alternatively, there are desires to replace yeastolate with defined active substances (Wu and Lee 1998).

Yeastolates contain undefined mixtures of amino acids, peptides, polysaccharides, vitamins, and minerals (Sommer 1996). Many efforts have been dedicated to screen yeastolate and to identify active components which support the cell growth and fermentation. The experimental approaches include testing known components (Smith et al. 1975; Wu and Lee 1998), finding deficient or limiting components in yeastolate by supplementing potential limiting components in bad lots of yeastolate (Zhang et al. 2003), and correlating the yield of fermentation product and the composition of yeastolate as characterised by techniques such as automated turbidimetry system (Potvin et al. 1997) and near-infrared spectroscopy (Kasprow et al. 1998). In these studies, it is not completely understood what components or any components other than the limiting ones are required for promoting microbial and cell growth. Overall, the results of these studies reflect the complexity of yeastolate composition and possible combination effects of its active components.

With the development of modern chromatography technology, it is possible to fractionate yeastolate and to evaluate the activity of each fraction. However, tremendous work would be required to evaluate the activity of each fraction and the combination of the active fractions. As an alternative, fractionation by organic solvent precipitation is commonly used in natural product chemistry, as it is easy, less expensive, scalable and ready to produce sufficient amounts of materials for bioassays (Scopes 1987). As the number of fractions is limited, it also fits to study the synergy among the fractions.

The objectives of the present study are to fractionate yeastolate through a sequential solvent (ethanol) precipitation and to evaluate the activity of each fraction on cell growth-promoting and protein production-enhancing. The study also aims at primarily characterizing the fractions and identifying potential active components to guide for further isolation of critical elements.

Materials and methods

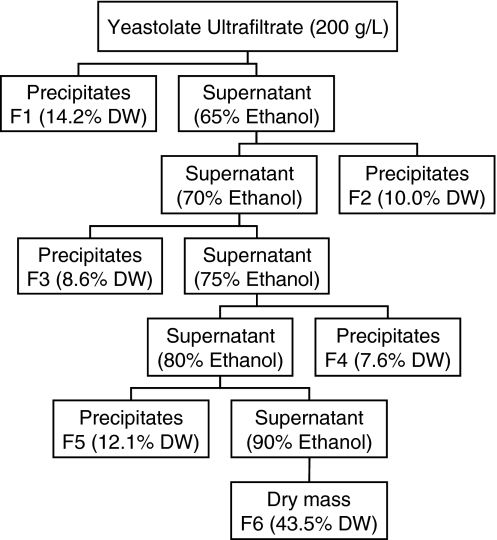

Yeastolate and preparation of yeastolate fractions

Difco TC yeastolate (Cat. No. 255772) was purchased from Becton Dickinson (Sparks, MD). The TC yeastolate was dissolved in Milli-Q water and ultra-filtrated by using a Pall lab tangential flow system equipped with Omega membrane (10 kD MWCO) (Pall Ltd., Mississauga, ON, Canada). The concentration of the yeastolate ultrafiltrate (YUF) was adjusted to 200 g L−1. The YUF was fractionated using sequential precipitation with different ethanol concentrations at 4 °C as illustrated in Fig. 1. Briefly, 50 ml of YUF (200 g L−1) was mixed with 92.8 ml of chilled anhydrous ethanol (Commercial Alcohols Inc., Brampton, ON) in a 250 ml plastic centrifuge tube (Corning, NY) to achieve 65% vol/vol ethanol (assuming additive volumes) in the mixture. The yeastolate–ethanol mixture was kept at 4 °C for 30 min and then centrifuged at 3800 rpm (Beckman, Model J-6B) for 20 min at 4 °C. The precipitated yeastolate components (F1) were collected. The supernatant from the first ethanol precipitation was mixed with more ethanol in order to further precipitate yeastolate components (F2). The precipitation with higher ethanol contents was performed three more times to get F3, F4 and F5. The remaining supernatant was designed as F6. All fractions were freeze-dried, dissolved in Milli-Q water to have a concentration of 100 g L−1, and sterilized by filtration.

Fig. 1.

Fractionation procedure of yeastolate ultrafiltrate by a sequential ethanol precipitation

Cells and media

Sf-9 insect cells were maintained in Sf 900 II medium (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON). IPL-41 medium was prepared by supplementing the IPL-41 basal medium (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS) with a lipid mixture (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON) according to Inlow et al. (1989). IPL-41 complete medium was prepared by supplementing the IPL-41 medium with 4 g L−1 of YUF, and termed as IPL-41 + YUF@(4 g L−1). Before use for the activity assay of yeastolate fractions, the Sf-9 cells were transferred to the IPL-41 + YUF@(4 g L−1) and grown in this medium for two or three passages.

Assay of yeastolate fraction activity on promoting cell growth

The cell culture grown in the IPL-41 + YUF@(4 g L−1) and at exponential phase (about 3–4 × 106 cells·mL−1) was centrifuged at 500g for 10 min. The cell pellet was resuspended to the IPL-41 medium and then centrifuged again (washing step). The cell pellet from the last centrifugation was resuspended in the IPL-41 medium to a cell density in the range of 0.7–1 × 106 cells·mL−1. Twenty millimilters of the cells were aliquoted into 125 ml polycarbonate Erlenmeyer flasks (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) to which YUF or its fraction (F1–F6) was individually added to have a final concentration of 2 g L−1 of that fraction. The cultures were maintained at 27 °C on an orbital shaker at 100 rpm, and were sampled regularly for the measurement of cell density.

Dose response study

The dose response of cell growth to the supplementation of YUF or F1 was examined by culturing Sf-9 cells in the IPL 41 medium supplemented with YUF or F1 at a respective concentration of 1, 2, 3 or 4 g L−1.

Effect of glucose, glutamine and vitamin supplements on cell growth

Concentrated glucose and glutamine solutions were added to cells grown in the IPL-41 medium supplemented with 3 g L−1 of F1 or YUF. This addition occurred on day 4 in order to increase the residual concentration of glucose and glutamine by 9 and 1.8 mmol L−1 respectively. This was to study the effect of glucose and glutamine supplements. The effect of a vitamin mixture (Bédard et al. 1994) was tested by adding 1× and 3× of the vitamin mixture solutions to an IPL-41 medium which already contained 3 g L−1 of F1 at the time of inoculation.

Interaction effect between yeastolate fractions on promoting cell growth

The effect of interaction between F1 and other fractions (F2–F6) on promoting cell growth was investigated by adding F1 and one of other fractions to the cultures using the IPL-41 medium.

Effect of yeastolate fraction on enhancing production of recombinant protein

The assay media were prepared by supplementing the IPL-41 medium with different amounts of YUF or F1. The Sf-9 cell cultures were at the exponential phase and had been grown in the IPL-41 + YUF@(4 g L−1) for two passages. These were transferred to the shake flasks containing different assay media and grown for one more passage. The cells, which had been conditioned with the assay medium, were centrifuged and resuspended at 2 × 106 cells·mL−1 in the respective fresh assay medium. The cultures were then aliquoted into shake flasks and infected at an MOI of 10 with the recombinant baculovirus expressing β-galactosidase. The activity of this protein was measured at 96 h post-infection.

Analytical procedures

Total nitrogen and total carbohydrates of YUF and its fractions were respectively determined using Kjeldahl method and phenol/sulfuric acid assay (Taylor 1995). Concentration profile of components in YUF and its fractions was characterized by a reversed phase HPLC using a C18 column and water-acetonitrile as a mobile phase. Free amino acids were measured by HPLC using the Waters AccQ.Tag™ method. Total amino acids were measured by the same method after hydrolysis with 6 N HCl at 110 °C for 20 h. Cystine and tryptophan are destroyed during the hydrolysis, and not reported for total amino acids. The cell density and viability were respectively determined with a Z2 Coulter particle count & size analyser (Coulter Electronics Ltd., Luton, Beds, UK) and by Trypan Blue exclusion. The residual glucose concentration in the culture supernatants was measured using the IBI Biolyzer Rapid Analysis System (Kodak, New Haven, CT). The quantitation of β-galactosidase has been described previously (Bédard et al 1994). The osmolality of medium was measured using the Advanced™ Micro-Osmometer, Model 3MO (Advanced Instruments, Inc. Needham, Heights, MA).

Results

Fractions derived from yeastolate

Five precipitated fractions (F1–F5) and one fraction (F6) from supernatant were obtained through a sequential ethanol precipitation of YUF. The yield of each fraction and characterization of some basic composition are presented in Table 1. As a general trend, the percentage of total carbohydrates and free amino acids in the precipitated fractions increased in the order from F1 to F5, or increased with the increasing ethanol concentration used for the precipitation. During the fractionation process, it was noticed that the viscosity of the precipitated fractions decreased in the order from F1 to F5. F6, prepared from the supernatant generated with 90% ethanol precipitation, was the largest fraction accounting for 41.7% dry weight of YUF used. F6 was low in carbohydrate content but high in total and free amino acids. The color of this fraction was orange–yellow, indicating a higher concentration of vitamin B2. Supplementation of YUF or its fractions at 4 g L−1 to IPL-41 medium only increased the medium osmolality by about 10 mOsm.

Table 1.

Characterization of yeastolate ultrafiltrate and its fractions

| Fractions | Fractionated by EtOH (%)a | Total carbohydrates (%) | Total nitrogen (%) | Total amino acids (%) | Free amino acids (%) | Dry mass recovered (%) | Cumulative recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Sup (0); ppt (65) | 23.4 | 9.3 | 44.22 | 19.0 | 16.8 | 16.8 |

| F2 | Sup (65); ppt (70) | 25.1 | 9.5 | 51.31 | 29.1 | 9.3 | 26.1 |

| F3 | Sup (70); ppt (75) | 28.7 | 9.2 | 47.47 | 30.2 | 9.4 | 35.5 |

| F4 | Sup (75); ppt (80) | 29.0 | 8.6 | 45.21 | 31.6 | 8.1 | 43.6 |

| F5 | Sup (80); ppt (90) | 35.0 | 8.7 | 44.62 | 31.5 | 12.9 | 56.5 |

| F6 | Sup (90) | 13.8 | 9.8 | 58.62 | 42.2 | 41.7 | 98.2 |

| YUF | N/A | 19.4 | 9.4 | 53.2 | 33.7 | N/A | N/A |

aSup (i); ppt (j) means that the fractionated material is soluble in i% EtOH/H2O and is precipitated by j% EtOH/H2O

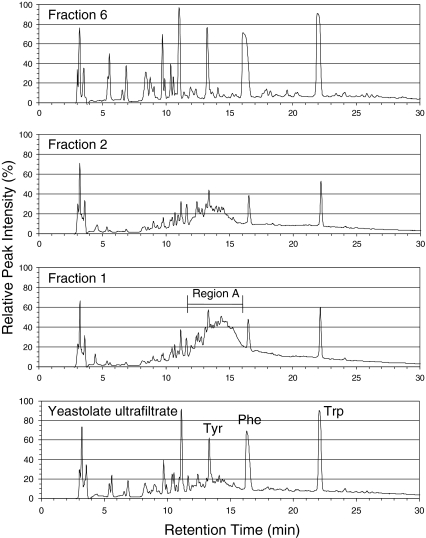

Figure 2 shows reversed phase HPLC chromatograms of YUF, F1, F2 and F6 fractions. The chromatograms of F3–F5 (not shown) were similar to the ones obtained for F1 or F2 except that the intensity of the peaks in region A further declined in the order F3–F5. The UV spectra of components in region A indicated the presence of peptide-like compounds. These chromatograms show that the ethanol precipitation did not result in a clear cut separation of yeastolate components.

Fig. 2.

Reversed phase HPLC chromatograms of yeastolate ultrafiltrate and its fractions monitored at 215 nm

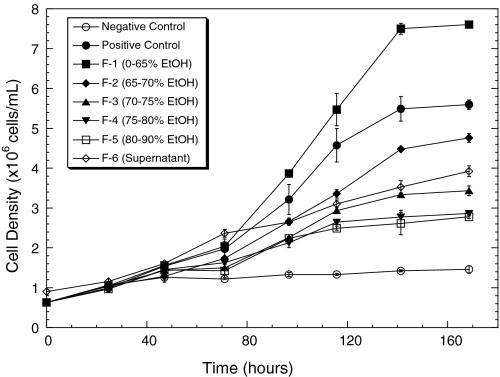

Cell growth promoting activity of yeastolate fractions

The growth-promoting activity of YUF and its fractions on Sf-9 cells were tested in the IPL-41 medium respectively supplemented with 2 g L−1 of YUF (positive control) or its fraction, instead of 4 g L−1 commonly used in the IPL-41 complete medium, in order to avoid the possibility that other nutrients in the medium become limiting factors during the test. Data in Fig. 3 indicate that the growth of Sf-9 cells in the IPL-41 devoid of YUF or its fraction (negative control) was very limited, and the maximum cell density was only 1.5 × 106 cells·mL−1. The supplementation of YUF or its fractions promoted the cell growth, and the maximum cell density was increased to 5.6, 7.5, 4.8, 3.4, 2.9, 2.8 and 3.9 × 106 cells·mL−1 respectively in the cultures supplemented with YUF, F1, F2, F3, F4, F5 and F6. The cell growth-promoting effect (activity) of the added YUF or its fractions, which is reflected by the difference between the maximum cell densities achieved in the negative control and the culture with YUF or its fraction, was 4.1, 6.0, 3.3, 1.9, 1.4, 1.3 and 2.4 × 106 cells·mL−1 respectively for YUF and F1–F6. When normalized with YUF (the positive control), the relative activity of the six fractions (F1–F6) was 149, 80, 48, 34, 32 and 60% activity of the positive control, respectively.

Fig. 3.

The growth curve of Sf-9 cell in the IPL 41 medium supplemented with 2 g l−1of yeastolate ultrafiltrate or its fraction

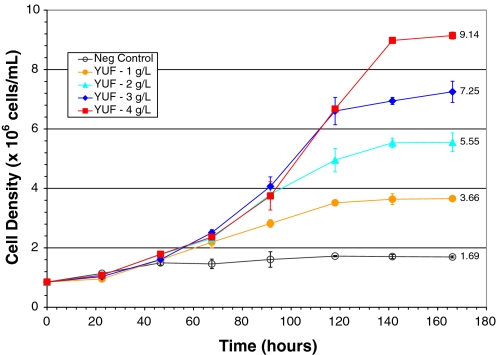

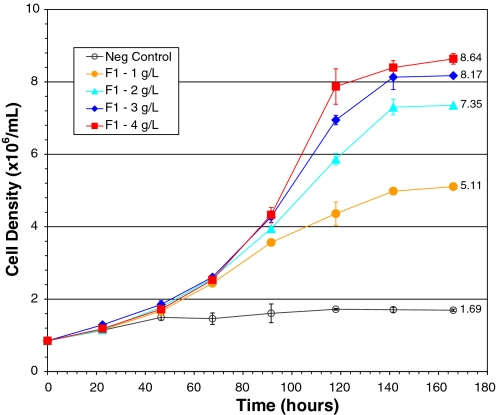

The extent of F1 on promoting Sf-9 cell growth was further examined using a dose response study. The maximum cell density achieved in the negative control and in the cultures supplemented with 1, 2, 3 and 4 g L−1 of YUF is presented in Fig. 4; the maxima recorded were 1.7, 3.7, 5.6, 7.3 and 9.1 × 106 cells·mL−1 respectively. By taking the increased cell density achieved in the culture supplemented with 4 g L−1 of YUF as positive control (100%), the increased cell density achieved in the cultures respectively supplemented with 1, 2 and 3 g L−1 of YUF was 26.4%, 51.8% and 74.6% of the positive control. Increases in cell density were proportional to the amounts of added YUF. Similarly, Fig. 5 shows that the maximum cell density in the culture supplemented with 1, 2, 3 and 4 g L−1 of F1 was 5.18, 7.35, 8.17 and 8.64 × 106 cells·mL−1. The increased cell density was respectively equivalent to 45.9%, 76.0%, 87.0% and 93.3% of that achieved in the positive control (4 g L−1 of YUF). The supplement of each additional g·L−1 of F1 resulted in an increase of cell density equivalent to 45.9%, 30.2%, 12.0% and 5.2% of the positive control. These results clearly indicate that F1 was more active than YUF when present in the IPL-41 at low concentrations. For example, the increased cell density in the culture supplemented with 1 g L−1 of F1 was 171% of that achieved in the culture with 1 g L−1 of YUF. However, the effect of additional supplement of F1 on the cell growth promoting gradually declined as the F1 dosage increased. In addition, the maximum cell density achieved in the culture with 4 g L−1 of F1 was lower than that obtained in the one with 4 g L−1 of YUF. The viability of cells from all cultures at the stationary phase was still higher than 95%.

Fig. 4.

Dose response of the yeastolate ultrafiltrate supplement in the IPL-41 medium on promoting SF-9 cell growth

Fig. 5.

Dose response of the supplement of the first precipitated fraction (F1) in the IPL-41 medium on promoting SF-9 cell growth

The residual concentrations of glucose and amino acids in each culture over the time course were analyzed. The data (not presented) show that glucose was depleted in the cultures supplemented with 3 and 4 g L−1 of F1 or YUF at the later stage of cultivation. The results of amino acid analysis indicate that only glutamine was depleted in the cultures supplemented with YUF or F1. Minor decreases of other amino acid concentrations were observed.

Effects of glucose, glutamine and vitamins addition on the maximum cell density

The maximum cell density of the cultures grown in the IPL-41 medium supplemented with 3 g L−1 of F1 and with glucose/glutamine or vitamins was normalized with the one obtained in the IPL-41 medium supplemented only with 3 g L−1 of F1 (control). The data show that the maximum cell density achieved in the cultures respectively supplemented glucose/glutamine, 1× vitamins or 3× vitamins was 102.2, 100.2 and 99.9% of that obtained in the control. Similarly, addition of glucose/glutamine in the culture already containing 3 g L−1 of YUF only increased the maximum cell density by 3.9%. These results indicate that, although glucose and glutamine were depleted in the cultures supplemented with ≥3 g L−1 of F1 or YUF, glucose and/or glutamine were not the main factors that limited the maximum cell density achieved in the above cultures. The vitamins were not the limiting factors either, although the vitamin content in F1 could be significantly changed or reduced by the fractionation process.

Interaction between fractions on promoting cell growth

A combination of the F1 and other fractions (F2–F6) on promoting Sf-9 cell growth was studied in IPL-41 medium. This could be the case if Sf-9 cells require components from different fractions for maximum cell growth. Table 2 shows that the maximum cell density was further increased by no more than 0.52 × 106 cells·mL−1 when additional g·L−1 of the precipitated fraction (F1–F5) was supplemented to the IPL-41 medium already consisting of 3 g L−1 of F1. While the maximum cell density in the same medium supplemented with 1 g L−1 of F6 was increased by 0.99 × 106 cells·mL−1. This may suggest that F6 provided additional components which promoted further growth of cells in the medium already consisting of 3 g L−1 of F1. A further assessment of the interaction between F1 and F6 on the cell growth promoting effect is presented in Table 3, and shows that the efficacy of F6 supplement on promoting cell growth was dependent on the concentration of F1 in the IPL-41 medium. The supplement of 1 g L−1 of F6 in the IPL-41 media already and correspondingly consisting of 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 g L−1 of F1 further improved the cell density by 0.81, 0.55, 0.74, 0.89 and 1.25 × 106 cells·mL−1 respectively. It is noteworthy that the increase by 1.25 × 106 cells·mL−1 indicates synergy effect between F1 (4 g L−1) and F6 (1 g L−1).

Table 2.

Effect of combination between different fractions on promoting cell growth

| Additive | Max cell density (×106 cells ml−1) | Cell density (×106 cells ml−1) increased over negative control | Cell density (×106 cells ml−1) increased over F1 (3 g L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None (negative control) | 1.82 ± 0.15 | 0 | |

| YUF (4 g L−1 as control) | 8.64 ± 0.13 | 6.82 | |

| F1 (3 g L−1 ) | 7.73 ± 0.06 | 5.91 | 0 |

| F1 (3 g L−1) + F1 (1 g L−1) | 8.23 ± 0.07 | 6.41 | 0.50 |

| F1 (3 g L−1) + F2 (1 g L−1) | 8.23 ± 0.42 | 6.41 | 0.50 |

| F1 (3 g L−1) + F3 (1 g L−1) | 8.25 ± 0.25 | 6.43 | 0.52 |

| F1 (3 g L−1) + F4 (1 g L−1) | 8.11 ± 0.28 | 6.29 | 0.38 |

| F1 (3 g L−1) + F5 (1 g L−1) | 7.85 ± 0.13 | 6.03 | 0.12 |

| F1 (3 g L−1) + F6 (1 g L−1) | 8.72 ± 0.11 | 6.90 | 0.99 |

Table 3.

Interaction effect between F1 and F6 on promoting Sf-9 cell growth

| Additive | Max cell density (×106 cells·ml−1) in cultures without or with additional supplement of F6 at 1 g L−1 | Cell density (×106 cells·mL−1) increased by additional supplement of F6 at 1 g L−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without F6 | With F6 | ||

| None (negative control) | 1.47 | 2.28 | 0.81 |

| F1 (1 g L−1) | 4.89 | 5.44 | 0.55 |

| F1 (2 g L−1) | 7.13 | 7.87 | 0.74 |

| F1 (3 g L−1) | 7.95 | 8.84 | 0.89 |

| F1 (4 g L−1) | 8.42 | 9.67 | 1.25 |

Activity of yeastolate fraction on enhancing protein production

The data in Table 4 reveal that the specific yield of β-galactosidase in the cultures grown in the F1 supplemented IPL-41 medium was constantly higher than that in the cultures supplemented with YUF. The best yield, equivalent to 122% of the positive control (supplemented with 4 g L−1 of YUF), was achieved in the culture supplemented with 1 g L−1 of F1. The specific yield of β-galactosidase in IPL-41 medium was 46% of that achieved in the positive control. A combination between the F1 and other fractions (F2–F6) on enhancing the production of β-galactosidase was not examined in this experiment.

Table 4.

Activity of yeastolate and its fractions on enhancing β-galactosidase production

| Additive | Specific yield of β-galactosidase (units/106 cells) | %Control |

|---|---|---|

| None | 27.8 | 46.0 |

| YUF (1 g L−1) | 56.0 ± 3.9 | 92.5 |

| YUF (4 g L−1) (positive control) | 60.5 ± 3.6 | 100.0 |

| F1 (1 g L−1) | 73.6 ± 1.8 | 121.5 |

| F1 (4 g L−1) | 62.3 ± 5.8 | 102.9 |

Discussion

YUF is the water-soluble portion of autolyzed yeast, and is an undefined mixture of amino acids, peptides, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals and other small molecules (Sommer 1996). Our experimental result showed that fractionation of YUF by ethanol precipitation was capable to capturing components which contributed more specially in promoting cell growth and enhancing protein production. F1, generated in the first step of YUF fractionation using 65% ethanol, promoted the cell growth most efficiently when added at relatively low concentrations (e.g., 1 g L−1) in IPL-41 medium. However, the superiority of F1 over YUF on the cell growth promoting activity gradually diminished as the dosage of F1 increased. This may suggest that, although concentrated in the component(s) active in the growth promoting, F1 lacked sufficient quantity of some other component that was also essential for the cell growth. This component(s) became a limiting factor in the IPL-41 medium supplemented with a high dosage (e.g., >2 g L−1) of F1. This hypothesis was confirmed by the superior effect of F6 over other fractions on promoting the cell growth when F6 was supplemented along with F1 (>3 g L−1). These results also indicate that Sf-9 cells required unique growth-promoting components present in both F1 and F6 to achieve a maximum cell growth. The active component(s) in F6 might not be very active in growth promoting when added alone, but synergistically promoted the activity of F1 (4 g L−1).

F1 was also more active than YUF in enhancing the production of β-galactosidase. The specific yield of β-galactosidase was even higher when F1 was present in the IPL-41 medium at lower concentrations such as 1 g L−1. This indicated that F1 concentrated in both growth-promoting component(s) and production-enhancing component(s). It appears that the concentration of active component(s) required by Sf-9 cells for enhancing the protein production was much lower than that required for the cell growth.

Glucose/glutamine or vitamins was added to the cultures using IPL-41 medium supplemented with 3 g L−1 of F1 to examine whether these components became growth limiting factors under the above conditions. The result indicates that glucose, glutamine and vitamins were not limiting factors although glucose and glutamine were depleted in cultures. While the insignificant effect of glutamine supplementation may suggest that Sf-9 cells were able to utilize other components as sources of amino acids, since it is known that cultured animal cells can metabolize dipeptides such as glycyl-l-glutamine (Minamoto et al. 1991) and peptides (Nyberg et al. 1999). No positive effect of vitamin supplementation may suggest that the vitamins provided by F1 and IPL-41 medium were still sufficient.

Considering the complexity of YUF composition and the work conducted by other researchers (Smith et al. 1975; Wu and Lee 1998), it was assumed that testing known compounds was not an effective approach to identify active components in YUF. Our approach was instead to characterize the reverse phase HPLC profiles of YUF and its fractions. These profiles indicated that there was overlapping in the YUF components present in the six fractions (F1–F6) although the concentration of individual component in each fraction was significantly altered. The overlapping in the YUF components is probably due to the relatively low resolution of solvent precipitation. The components overlapped but with different concentrations among the six fractions. This may explain why the cell growth promoting activity of the fractions from F1 to F5 decreased gradually. A correlation between the activity of the precipitated fraction and the intensity of peaks in the region A in the reversed phase HPLC chromatograms is suggested. Future chromatographic studies may allow for the collection of components from A region. Evaluation of their activities may provide an improved understanding of whether the activity of F1 was mainly due to these peptide-like components.

Many cell culture medium formulas utilize YUF and/or other protein hydrolysates as a replacement for serum. The views on the possible roles of hydrolysates are divided; do the hydrolysates confer a nutritional benefit or, do they in addition contain bioactive peptides that could mimic growth factors. Schlaeger (1996) and Heidemann et al. (2000) have hypothesized that the hydrolysates provide cells with various low molecular weight nutrients that may be mimicked by an optimized initial free amino acid content of the protein-free medium. While Rasmussen et al. (1998) and Burteau et al. (2003) concluded that peptides in the hydrolysates could function as growth factors for CHO cells. Data from this work shows that F1 promoted Sf 9 cell growth most effectively in spite of its lowest concentration of free amino acids (Table 1). This result may suggest that the cell growth-promoting effect of F1 was due to bioactive peptides instead of free amino acids. These bioactive peptides in F1 were more likely large peptides which were precipitated by 65% of ethanol. This result is in agreement with Burteau et al. (2003) who pointed out that most of the beneficial effects of hydrolysates seem to correlate with their content in “large” oligopeptides. Franek et al. (2000) also demonstrated that oligopeptides in plant protein hydrolysates possess positive effects on promoting cell growth.

In summary, the present work demonstrated that sequential ethanol precipitation was able to concentrate growth-promoting components from yeastolate. The growth promoting components were less soluble in ethanol, and were more likely large peptides. This work was a significant step forward in the isolation of growth promoting-components from YUF. We also illustrated that Sf-9 cells require components present in more than one fraction to achieve maximal cell growth. This finding points out that further isolation of active components from two different fractions may require intensive experimental work.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Louis Bisson and Alice Bernier for providing assistance in analysis of amino acids and size exclusion chromatography. The authors also appreciated helpful discussions with Cynthia Elias and Faustinus Yeboah.

References

- Bédard C, Kamen A, Massie B (1994) Maximization of recombinant protein yield in the insect cell/baculovirus system by one-time addition of nutrients to high-density batch cultures. Cytotechnol 15:129–138 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bridson EY, Brecker A (1970) Design and formulation of microbial culture media. In: Methods in microbiology, vol. 3A. Academic Press, pp 252–256

- Burteau CC, Verhoeye FR, Mols JF, Ballez JS, Agathos SN, Schneider YJ (2003) Fortification of a protein-free cell culture medium with plant peptones improves cultivation and productivity of an interferon-gamma-producing CHO cell line. In vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 39:291–296 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Franek F, Hohenwarter O, Katinger H (2000) Plant protein hydrolysates: preparation of defined peptide fractions promoting growth and production in animal cells cultures. Biotechnol Prog 16:688–692 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa A, Yamashita H, Kondo S, Kiyota T, Hayashi H, Yoshizaki H, Murakami A, Shiratsuchi M, Mori T (1988) Proteose peptone enhances production of tissue-type plasminogen activator from human diploid fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 150:1230–1236 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Heidemann R, Zhang C, Qi H, Rule JL, Rozales C, Park S, Chuppa S, Ray M, Micheals J, Konstantin K, Naveh D (2000) The use of peptones as medium additives for the production of a recombinant therapeutic protein in high density perfusion cultures of mammalian cells. Cytotechnol 32:157–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ikonomou L, Bastin G, Schneider YJ, Agathos SN (2001) Design of an efficient medium for insect cell growth and recombinant protein production. In vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 37:549–559 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Inlow D, Shauger A, Maiorella B (1989) Insect cell culture and baculovirus propagation in protein-free medium. J Tissue Culture Methods 12:13–16 [DOI]

- Kasprow RP, Lange AJ, Kirwan DJ (1998) Correlation of fermentation yield with yeast extract composition as characterized by near-infrared spectroscopy. Biotechnol Prog 14:318–325 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kelly M (1983) Yeast extract. In: Godfrey T, Reichelt M (eds) Industrial enzymology, the application of enzymes in industry. Nature press, New York, pp 457–464

- Maiorella B, Inlow D, Shauger A, Harano D (1988) Large-scale insect cell-culture for recombinant protein production. Bio/Technol 6:1406–1410 [DOI]

- Minamoto Y, Ogawa K, Hideki A, Iochi Y, Misugi K (1991) Development of a serum-free and heat sterilizable medium and continuous high-cell density cell culture. Cytotechnol 5:S35–S51 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nyberg GB, Balcarcel RR, Follstad BD, Stephanopoulos G, Wang DIC (1999) Metabolism of peptide amino acids by Chinese hamster ovary cells grown in a complex medium. Biotechnol Bioeng 62:423–335 [PubMed]

- Peptone Technical Manual, BD Biopharmaceutical Production, BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD, USA. May 2002

- Potvin J, Fonchy E, Conway J, Champagne CP (1997) An automatic turbidimetric method to screen yeast extract as fermentation nutrient ingredients. J Microbial Methods 29:153–160 [DOI]

- Rasmussen B, Davis R, Thomas J, Reddy P (1998) Isolation, characterization and recombinant protein expression in Veggie-CHO: a serum-free CHO host cell line. Cytotechnol 28:31–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schlaeger EJ (1996) The protein hydrolysate, Primatone RL, is a cost-effective multiple growth promoter of mammalian cell culture in serum-containing and serum-free media and displays anti-apoptosis properties. J Immunol Methods 194:191–199 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Scopes RK (1987) Protein purification, 2nd edn. Chapter 3: separation by precipitation. Springer-Verlag, NY

- Smith PF, Langworthy TA, Smith MR (1975) Polypeptide nature of growth requirement in yeast extract for Thermoplasma acidophilum. J Bacteriol 124:884–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sommer R (1996) Yeast extracts: production, properties and components. In: 9th International Symposium on Yeasts, Sydney, August 1996

- Taylor KACC (1995) A modification of the phenol/sulfuric acid assay for total carbohydrates giving more comparable absorbances. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 53:207–214

- Wu J, Lee KD (1998) Growth promotion by yeastolate and related components on insect cells. Biotechnol Tech 12:67–70 [DOI]

- Zhang J, Reddy J, Buckland B, Greasham R (2003) Toward consistent and productive complex media for industrial fermentations: studies on yeast extract for a recombinant yeast fermentation process. Biotechnol Bioeng 82:640–652 [DOI] [PubMed]