Abstract

Infections of the sacroiliac joint are uncommon and the diagnosis is usually delayed. In a retrospective study, 17 patients who had been treated for tuberculosis sacroiliitis between 1994 and 2004 were reviewed. Two patients were excluded due to a short follow-up (less than 2 years). Low back pain and difficulty in walking were the most common presenting features. Two patients presented with a buttock abscess and spondylitis of the lumbar spine was noted in two patients. The Gaenslen’s and FABER (flexion, abduction and external rotation) tests were positive in all patients. Radiological changes included loss of cortical margins with erosion of the joints. An open biopsy and curettage was performed in all patients; histology revealed chronic infection and acid-fast bacilli were isolated in nine patients. Antituberculous (TB) medication was administered for 18 months and the follow-up ranged from 3 to 10 years (mean: 5 years). The sacroiliac joint fused spontaneously within 2 years. Although all patients had mild discomfort in the lower back following treatment they had no difficulty in walking. Sacroiliac joint infection must be included in the differential diagnosis of lower back pain and meticulous history and clinical evaluation of the joint are essential.

Résumé

L’infection des sacro-iliaques est rare et le diagnostic est souvent retardé. Dans une revue rétrospective 17 patients étaient traités pour une tuberculose sacro-iliaque entre 1994 et 2004. Deux patients étaient exclus à cause d’un suivi de moins de 2 ans. Des lombalgies et des difficultés de marche étaient les signes les plus fréquents. Deux patients présentaient un abcés de la fesse et deux autres une spondylite lombaire. Les test de Faber et de Gaenslen étaient positif chez tous les patients. Les signes radiologiques comportaient des érosions articulaires et des lyses corticales. Un curetage- biopsie était fait chez tous les patients et un bacille acido-résistant était isolé chez 9 patients. Un traitement anti-tuberculeux était administré pour 18 mois et le suivi était de 3 à 10 ans (en moyenne 5 ans). L’articulation sacro-iliaque se fusionnait dans les 2 ans. Bien que tous les patients gardaient un certain disconfort lombaire, ils n’avaient pas de difficulté de marche. L’infection sacro-iliaque doit faire partie des diagnostics différentiels des lombalgies et une évaluation méticuleuse de l’histoire et de la clinique est essentielle.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains the most common cause of death worldwide, affecting approximately one-third of the world’s population [2], most notably in the third world countries [5]. Skeletal tuberculosis comprises approximately 3–5% of all tuberculosis of which approximately 10% occurs at the sacroiliac joint [5, 7, 14, 16].

Sacroiliac joint tuberculosis is frequently missed because of the vague symptoms [8]. More often than not, patients are examined in the supine position thus overlooking the sacroiliac joint. The sacroiliac joint may be secondarily involved following a psoas abscess affecting the lower lumbar spine [20]. Prior to the introduction of anti-TB treatment Seddon and Strange [19] and Soholt [20] reported over 200 cases with a high morbidity and mortality. The incidence has since declined and Kim et al. [12] reported 16 cases, which were treated over a 20-year period. The natural history of sacroiliac tuberculosis is bony ankylosis [17, 19, 20].

Materials and methods

A retrospective study of sacroiliac joint tuberculosis was performed in the spinal unit from January 1994 to December 2004. Seventeen cases were retrieved from the patient records for this period. Two patients were excluded as they had been followed up for less than 2 years. Fourteen patients had unilateral involvement and one was bilateral. There were 13 females and 2 males and the age ranged from 15 to 60 years (mean: 27 years). The duration of symptoms ranged from 11 weeks to 39 weeks (mean: 18 weeks).

Persistent low back pain and difficulty with walking were noted in all patients. The remaining two patients presented with an abscess over the affected sacroiliac joint. All patients had constitutional symptoms involving loss of weight, poor appetite and night sweats. Clinical examination revealed tenderness along the affected sacroiliac joint in all patients. Stress tests of the sacroiliac joint, namely the pelvic compression test, the FABER [13] (flexion, abduction and external rotation) test and the Gaenslen’s test were positive. Ranges of motion at the hips were only painful at the extreme of flexion and extension. The straight leg raising test was negative in all patients.

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated (mean: 78 mm/h ) in all patients (range: 45–138 mm/h) whereas the full blood count (FBC) revealed a normocytic, normochromic anaemia (range: 7.9–11.3 gm/dl, mean: 10.1 gm/dl). Radiological studies included bone scans, X-rays as well as computed tomography (CT) scans.

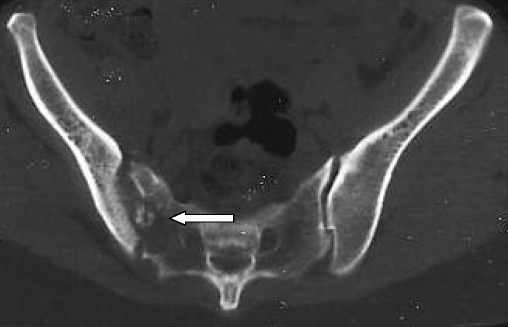

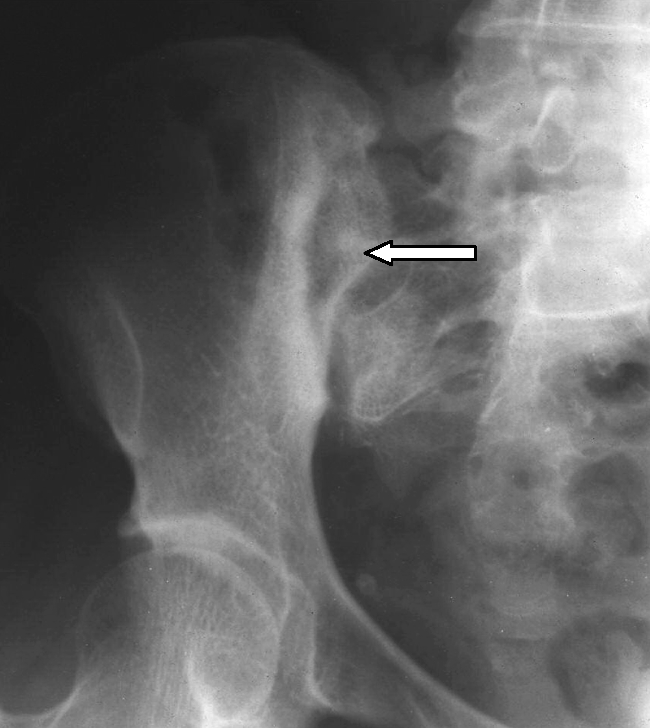

Bone scans (technetium 99) revealed increased uptake in the affected joint in all patients. The features seen on X-rays included joint space widening, sclerosis of the joint margins and periarticular osteopaenia (Fig. 1). CT scans revealed joint space widening, sclerosis of the joint margins and sequestra within the joint (Fig 2). An open biopsy and curettage of the joint from a posterior approach was performed and specimens were sent for microscopy and culture and histology. Patients were mobilised on crutches and commenced on a course of anti-TB medication for 18 months. Follow-up ranged from 3 to 10 years (mean: 5 years).

Fig. 1.

Tuberculosis of the right sacroiliac joint. Arrow indicates the widened joint space as well as the sclerosis of the joint margins

Fig. 2.

CT scan demonstrating an infective process of the left sacroiliac joint with evidence of a sequestrum, calcification and destruction of the joint (arrow)

Results

At operation, pus, granulation tissue and sequestra were found in all patients. The wounds healed without any complications. Histology revealed causative granulomas in 15 patients and acid-fast bacilli were isolated in nine patients, using the Lowenstein-Jensen medium. Bony healing was radiologically evident at 2 years (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

CT scan demonstrating a solid bony fusion 2 years after open biopsy and chemotherapy

Pain at the affected joint progressively subsided following posterior decompression of the joint and antituberculous medication. At final follow-up, the patients had minimal discomfort over the affected joint and were fully weight bearing.

Discussion

Infective sacroiliitis is uncommon, represented by sporadic case reports in the literature [1, 3–8, 12, 17–20]. The joint is a synchondrosis and the hyaline cartilage is thinner on the ilial surface when compared to the sacral side. The presenting symptoms of sacroiliitis are vague and the distribution of pain varies due to close relationship between the joint, the lumbosacral plexus and the ability of the abscess to track in any direction [3, 12, 18, 20]. Pain is worsened by walking, sitting and physical activity [3, 13]. A false positive straight leg raising test may be present, due to capsular distention irritating the lumbosacral plexus [3]. Rectal examination may elicit tenderness over the affected sacroiliac joint. The infection in the early stages is often misleading and may mimic pathology in the lower back as well as osteitis of the ilium. In bilateral sacroiliac disease there is usually a lesion in the lumbar spine, as noted in one of our patients. From the lumbar spine, the psoas abscess may spread to involve the sacroiliac joint [19].

In the early stages of the disease, capsular distention is evident on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Associated bone oedema and destruction are also noted [1, 11]. X-rays reveal haziness initially, but this is replaced by joint widening, sclerosis of the margins and possible sequestrae in the joint in the more advanced stages [12, 17, 19, 20]. Bone scans are helpful when the diagnosis is not clear [7, 8]. CT scans demonstrate the joint space widening, sequestrae and calcification more clearly than X-rays [1, 3, 7, 8, 11, 12].

A diagnostic aspiration or closed needle biopsy of the sacroiliac joint is appropriate when the disease is in its early stages with minimal joint destruction [9, 11, 12, 15, 20]. Pyogenic infections and other atypical infections must be excluded. Kim et al. performed an open biopsy in 12 of 16 patients. They found that fusion occurred earlier in patients who had an open biopsy when compared to the four patients treated conservatively with antituberculous medication only [12]. Their results are in keeping with the findings of our previous study [17]. Soholt showed that bony ankylosis occurred in both the operative and non-operative groups, and the advantage of open biopsy was that the process of healing might be faster [17, 20]. Seddon and Strange described progressive widespread infection in 10% of patients leading to subluxation of both sacroiliac joint and pubic symphysis, which may be attributed to poor nutrition and the unavailability of anti-TB medication in 1940. They also reported the presence of one or more sinuses in 42% of patients with a mortality of 20% [19]. Their only criterion for fusion of the sacroiliac joint was a painful fibrous ankylosis. We previously noted that the aspirates from the sacroiliac joint were negative for tuberculosis in 14% of patients, although they had positive evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis [17]. We find that the advantages of an open biopsy in the late stages of the infection include eradication of pus and necrotic tissue and obtaining an adequate tissue sample for culture, sensitivity and histology.

There are differences in the yield of tissue samples following a closed and open biopsy. High yield (between 90–100%) from both histology and culture reports were noted in several studies following an open biopsy of the sacroiliac joint [10, 12, 19]. Similarly, high yields were noted in closed needle biopsy of the sacroiliac joint as shown by Pouchot et al. (81%) and Miskew et al. (87%). In this study, the yield was 100%, but acid-fast bacilli were only isolated in 60% of cases. This may be attributed to the paucibacillary nature of musculoskeletal tuberculosis. A large variety of organisms may affect the sacroiliac joint. In a previous study of 31 patients with sacroiliitis, there were 14 cases of TB, 7 staphylococcal, 6 gonococcal and 4 typhoid [17]. In the TB group no organisms were isolated in the aspirates of two patients. In the absence of TB elsewhere (pulmonary, spinal), a tissue diagnosis is essential especially when the aspirates are negative.

Conclusion

A clinical diagnosis of sacroiliac joint infection includes a thorough history and a meticulous examination of the lower back and the sacroiliac joint. Evidence of calcification, sequestrae and joint destruction on X-ray or CT scan is suggestive of tuberculous infection. In the early stages of the infection aspiration using a closed needle biopsy is recommended. An open biopsy is essential when the aspirate yields no growth and in patients who present late with severe joint destruction as in our group of patients. Following the diagnosis and commencement of chemotherapy, bony ankylosis is to be expected.

References

- 1.Attarian DE (2001) Septic sacroiliitis: the overlooked diagnosis. J South Orthop Assoc 10(1):57–60 [PubMed]

- 2.Babhulkar SS (2002) Clinical comment. Clin Orthop 398:2–3

- 3.Chen WS (1995) Chronic sciatica caused by tuberculous sacroiliitis-a case report. Spine 20(10):1194–1196 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Coy JT, Wolf CR, Brower TD, Winter WG (1976) Pyogenic arthritis of the sacro-iliac joint. Long-term follow-up.J Bone Joint Surg Am 58(6):845–849 [PubMed]

- 5.Davies PD, Humphries MJ, Byfield SP, Nunn AJ, Darbyshire JH, Citron KM, Fox W (1984) Bone and joint tuberculosis. A survey of notifications in England and Wales. J Bone Joint Surg Br 66(3):326–330 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Dunn EJ, Bryan DM, Nugent JT, Robinson RA (1976) Pyogenic infections of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Orthop 118:113–118 [PubMed]

- 7.Goldberg J, Kovarsky J (1983) Tuberculous sacroiliitis. South Med J 76(9):1175–1176 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gordan G, Kabins SA (1980) Pyogenic sacroiliitis. Am J Med 69:50–56 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hendrix RW, Lin PJ, Kane WJ (1982) Simplified aspiration or injection technique for the sacroiliac joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 64(8):1249–1252 [PubMed]

- 10.Isaacson AS, Whitehouse WM (1949) Spontaneous sacroiliac obliteration in patients with tuberculosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 31(2):306–311 [PubMed]

- 11.Kim NH, Lee HM, Suh JS (1994) Magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of tuberculous spondylitis. Spine 19(21):2451–2455 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Kim NH, Lee HM, Yoo JD, Suh JS (1999) Sacroiliac joint tuberculosis—classification and treatment. Clin Orthop 358:215–222 [PubMed]

- 13.Laeslett M, Williams M (1994) The reliability of selected pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint pathology. Spine 19(11):1243–1248 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Martini M, Ouahes M (1988) Bone and joint tuberculosis: a review of 652 cases. Orthopedics 6:861–866 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Miskew DB, Block RA, Witt PF (1979) Aspiration of infected sacroiliac joints. J Bone Joint Surg Am 61(7):1071–1072 [PubMed]

- 16.Nicholson RA (1974) Twenty years of bone and joint tuberculosis in Bradford. A comparison of the disease in the indigenous and Asian populations. J Bone Joint Surg Br 56(4):760–765 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Osman AA, Govender S (1995) Septic sacroiliitis. Clin Orthop 313:214–219 [PubMed]

- 18.Pouchot J, Vinceneux P, Barge J, Boussougant Y, Grossin M, Pierre J, Carbon C, Kahn MF, Esdaile JM (1988) Tuberculosis of the sacroiliac joint: clinical features, outcome and evaluation of closed needle biopsy in 11 consecutive cases. Am J Med 84:622–628 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Seddon HJ, Strange FG (1940) Sacroiliac tuberculosis. Br J Surg 28:193–221 [DOI]

- 20.Soholt ST (1951) Tuberculosis of the sacroiliac joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 33(1):119–129 [PubMed]