Abstract

Pectoralis major tendon rupture is a relatively rare injury, resulting from violent, eccentric contraction of the muscle. Over 50% of these injuries occur in athletes, classically in weight-lifters during the ‘bench press’ manoeuvre. We present 13 cases of distal rupture of the pectoralis major muscle in athletes. All patients underwent open surgical repair. Magnetic resonance imaging was used to confirm the diagnosis in all patients. The results were analysed using (1) the visual analogue pain score, (2) functional shoulder evaluation and (3) isokinetic strength measurements. At the final follow-up of 23.6 months (14–34 months), the results were excellent in six patients, good in six and one had a poor result. Eleven patients were able to return to their pre-injury level of sports. The mean time for a return to sports was 8.5 months. The intraoperative findings correlated perfectly with the reported MRI scans in 11 patients and with minor differences in 2 patients. We wish to emphasise the importance of accurate clinical diagnosis, appropriate investigations, early surgical repair and an accelerated rehabilitation protocol for the distal rupture of the pectoralis major muscle as this allows complete functional recovery and restoration of full strength of the muscle, which is essential for the active athlete.

Résumé

La rupture du tendon principal du pectoral est un traumatisme rare. Plus de 50% de ces traumatismes surviennent chez des athlètes lors du levé de poids. Nous présentons 13 cas de ces ruptures avec un traitement chirurgical. L’IRM a confirmé le diagnostic chez tous les patients. Les résultats ont été analysés en utilisant une échelle visuelle analogique, une évaluation fonctionnelle de l’épaule et la mesure de la force. Au suivi final de 23,6 mois, les résultats sont excellents pour six patients, bons pour six et mauvais pour un. Onze patients ont retrouvé leur niveau sportif initial. Le temps moyen de reprise du sport était de 8,5 mois. Les constatations opératoires concordaient avec l’aspect IRM chez 11 patients. Nous insistons sur la précision du diagnostic clinique, les examens appropriés, la réparation chirurgicale rapide et la rééducation précoce après la rupture distale du grand pectoral pour permettre une récupération complète, ce qui est essentiel chez les athlètes.

Introduction

Rupture of the pectoralis major is a rare injury that was first described by Patissier [16] in 1822 in Paris, followed by Letenneur [9] in 1861. To date just over 150 cases have been reported. The injury results from violent, eccentric contraction of the muscle and tends to present in athletes as an uncommon sports injury. By far the most common sport associated with this injury is weight lifting, particularly during the ‘bench press’. Other sports include wrestling, water skiing and rugby [2]. Although ruptures remain rare, the injury has become more prevalent in the past 30 years as the numbers of both recreational and professional athletes have increased.

Our study includes a short review of the literature, description of the anatomy and mechanisms of the injury, presenting symptoms and signs, initial investigations and the evaluation of the results of the surgical repair of pectoralis major muscle rupture.

Anatomy

The pectoralis major muscle is a powerful adductor, internal rotator and flexor of the shoulder. It arises as a broad sheet with two heads of origin: the upper clavicular head and the lower sterno-costal head. The two parts of the muscle converge laterally and insert on the lateral lip of the bicipital groove over an area of 5 cm. The fibres of the sterno-costal head pass underneath the clavicular head fibres forming the deeper posterior lamina of the tendon, which rotates 180 degrees so that the inferior-most fibers are inserted at the highest or most proximal point of the humerus. The clavicular head fibres form the anterior lamina of the tendon, which inserts more distally. As a result of the anatomy, the fibres of the sterno-costal head are maximally stretched during activities when the arm is abducted, externally rotated and extended such as during a bench press. This predisposes the inferior portion of the tendon to fail first [18]. Although most cases are undoubtedly partial, most reported injuries have been complete ruptures [2], predominantly affecting the distal musculo-tendinous junction or insertion of the tendon.

Mechanism

The mechanism of injury of a pectoralis major rupture is either due to direct injury or indirect trauma due to extreme muscle tension or a combination of both. Several studies have reported an increased incidence of injuries because of excessive muscle tension rather than direct trauma [2, 6, 11, 19]. By far the most common mechanism of injury is the ‘bench press’ during which the arm is abducted and externally rotated and during which the pectoralis major tendon is under maximum tension. Most injuries occur as the weight is lowered down to the chest. The muscle normally helps to ‘brake’ the motion, preventing the weight from falling on the chest. If this eccentric contraction is uncoordinated either as a result of muscle fatigue or weakness, the individual tries to favour that side and allows the weight to slip to one side. This results in sudden eccentric contraction of the pectoralis major, leading to rupture. Another common mechanism is a severe force applied to a maximally contracted muscle as a consequence of an attempt to break a fall or during a rugby tackle. There also appears to be a correlation between the mechanism of injury and the site of rupture. Direct trauma causes tears of the muscle belly, whereas excessive tension or indirect trauma causes avulsion of the humeral insertion or disruption at the musculo-tendinous junction.

Materials and methods

Materials

Thirteen patients underwent surgical repair for a distal rupture of the pectoralis major muscle at the Sports Surgery Department of the University Of Calgary, Canada, from February 1997 to July 2002. The patients were young athletes; the average age was 28.6 years (21–35). All were males. There were five students, two manual workers, two steer wrestlers, one doctor, one dentist, one policeman and one businessman. Seven of the ruptures treated were left sided and six were right sided. Only one patient was a smoker. Three patients reported a past history of anabolic steroid use. The injury occurred while doing a ‘bench press’ in six cases, during steer wrestling in three cases, during an altercation in two cases, during a fall in one case and during the closed reduction of a dislocated shoulder in one case [17]. All resulted from a violent eccentric contraction of the pectoralis major muscle.

Diagnosis of injury

The patients presented with the classic history of a tearing sensation in the axilla and on examination revealed local tenderness, bruising and loss of contour of the pectoralis major muscle (Fig. 1). Significant weakness of adduction and internal rotation of the arm were also noted.

Fig. 1.

Clinical presentation: swelling, bruising and loss of contour of the pectoralis major and anterior axillary fold

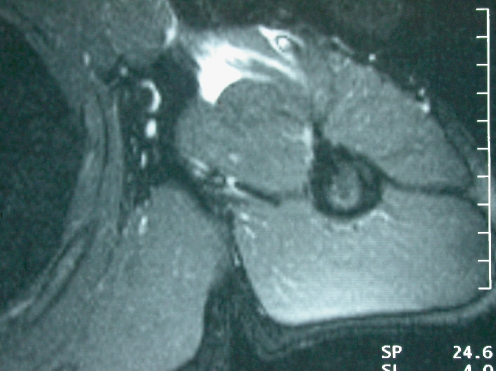

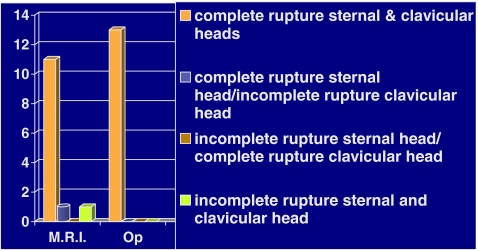

Plain radiology generally showed a loss of the pectoralis major shadow and loss of the normal anterior axillary fold. All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging, which confirmed the site and extent of the rupture precisely in 11 cases (Fig. 2). In two cases minor differences were discovered at surgery where suspected incomplete ruptures were found to be complete (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Axial oblique magnetic resonance image showing a complete rupture of the pectoralis major tendon

Fig. 4.

MRI: surgical correlation

Management

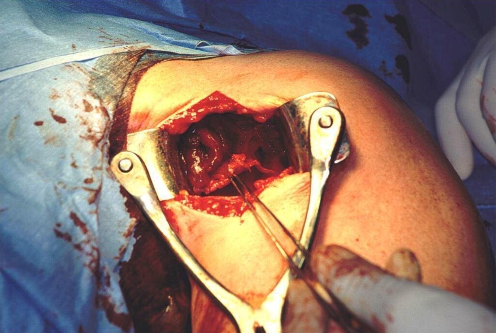

The mean time to surgery was 16 days (range 5–35 days). All operations were performed as day-case procedures. Intraoperatively, ten patients were found to have a complete tendon avulsion of the humeral insertion (type D), two patients had intra-tendinous ruptures (type F) and one patient had a bony flake avulsion of the tendon (type E) (Berson’s modification of Tietzen’s classification). The tear was approached via a delto-pectoral crease-line incision. The underlying haematoma was evacuated and the torn tendon carefully identified (Fig. 3). The lateral lip of the bicipital groove was exposed and cleared of soft tissue. The distal end of the tendon was reattached using ‘Mitek’ anchors (DePuy Mitek, Norwood, Mass.) and corkscrew suture anchors (Arthrex, Naples, Fla.). The repair was tested intraoperatively and the ‘safe arc’ of the external rotation was determined and documented. All patients were immobilised postoperatively in a shoulder immobiliser for 2 weeks.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative photograph demonstrating complete distal rupture of the pectoralis major

Rehabilitation

The accelerated rehabilitation protocol involved: (1) elbow exercises from day 1. (2) Isometric rotator cuff and pectoralis major strengthening was permitted with the shoulder in neutral rotation at 2 weeks along with passive external rotation within the documented ‘safe arc’. (3) Progressive physiotherapy included range of motion, strengthening and endurance exercises. Regular follow-ups were arranged to evaluate shoulder function, with the average duration being 23.6 months (14–34 months).

Functional results were analysed using:

Visual analogue scores for pain.

Functional shoulder evaluation score.

Isokinetic strength assessment.

Results

The functional results were rated as excellent, good, fair and poor (Table 1).

Table 1.

Functional result categorisation

| Excellent | Good | Fair | Poor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain free | Mild/infrequent pain | Pain on activity | Constant pain |

| ROM-full | Slight reduction in ROM | Restricted ROM | |

| No cosmetic complaint | No cosmetic complaint | Poor cosmetic result | Poor cosmetic result |

| <10% isokinetic strength deficit | <20% isokinetic strength deficit | >20% isokinetic strength deficit | Failure |

| Return to normal sport | Return to normal sport | Impairment of function affecting return to ADL |

Six patients had excellent results with a full range of shoulder motion and good muscular strength; six patients had good results, and one patient had a poor result. Two complications were reported. One patient had a postoperative haematoma that required evacuation (poor result), and one patient had a re-rupture of the tendon 3 1/2 months post-surgery during a fight. He underwent a second repair with a good functional outcome. All patients were able to return to sports, with 11 being able to return to their pre-injury level. Two competitive athletes were able to return to a less competitive level after their operation. The mean duration for a return to sports was 8.5 months (range 6–12 months).

Discussion

Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle can occur from infancy to old age, but sports-related injuries tend to occur from the 2nd to the 4th decades [17]. The majority of cases occur in athletes involved in weight-lifting, wrestling, football, rugby and wind surfing [2, 7, 15, 18, 20]. By far the most common method of injury is the ‘bench press’ as was noted in seven of the cases in our study.

The cause of rupture of the pectoralis major is multifactorial. Kannus and Jozsa [6] in 1991 stated that for a tendon to fail, it must have a focal area of degeneration. We postulate that although asymptomatic prior to the injury, these patients have some degeneration of their tendons resulting from the repetitive stress involved with regular weight training, thus contributing to the injury.

Distal ruptures of the pectoralis major are usually complete [6], and this was further demonstrated by this study. MR imaging has been shown to be valuable in determining the extent and site of tendon injuries [2, 4, 8, 14]. The most important images appear to be the axial oblique and coronal views.

Conservatively treated individuals demonstrated a marked deficit in the peak torque and work/repetition using the Cybex isokinetic testing [19]. Zeman et al. have reported that four out of five injured athletes who did not undergo surgical repair failed to return to their previous level of athletic functional ability [20]. Aarimaa et al. in a large series of 33 anatomically repaired cases of rupture of the pectoralis major have reported the best outcomes in ruptures repaired acutely, compared to those who underwent a delayed repair [1]. In an extensive meta-analysis of Bak et al., surgical treatment had significantly better outcomes compared with conservative or delayed repair [2]. We agree with other authors that acute surgical repair ensures good to excellent results in up to 90% of the cases [12, 15] as compared to 70% when treated non-operatively. Although both methods restore a full range of motion and pain relief, surgery is essential for restoration of normal strength and greater recovery of peak torques and work performed, especially for the athlete [2, 3, 7].

The technique for surgical repair varies from suturing the tendon to the periosteum [12], to the remaining tendon [11] or clavi-pectoral fascia [10]. Osseous fixation can be achieved through drill holes [7, 12, 15], barbed staples [5] and anchors [13].

Our study introduces the concept of the ‘safe arc’ and early functional rehabilitation program, which allows an early return to sports and activities of daily living.

Conclusion

Early surgical repair of distal pectoralis major tendon ruptures and an accelerated rehabilitation protocol provide reliable restoration of shoulder function and strength, allowing an early return to sports and functional activity. We believe MRI scanning is important in accurately determining the severity and the site of injury, which aids preoperative planning.

References

- 1.Aarimaa V, Rantanen J, Heikkila J, Helttula I, Orava S (2004) Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med 32(5):1256–1262 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Bak K, Cameron EA, Henderson IJP (2000) Rupture of the pectoralis major: a meta-analysis of 112 cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 8:113–119 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Berson B (1979) Surgical repair of the pectoralis major muscle in an athlete. Am J Sports Med 7:348–350 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Connell DA, Potter HG, Sherman MF, Wickiewicz TL (1999) Injuries of the pectoralis major muscle: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology 210(3):785–791 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Egan TM, Hall H (1987) Avulsion of the pectoralis major tendon in a weight lifter. Repair using a barbed staple. Can J Surg 30:434–435 [PubMed]

- 6.Kannus P, Jozsa L (1991) Histopathological changes preceeding spontaneous rupture of a tendon. A controlled study of 891 patients. J Bone Joint Surg 73A [PubMed]

- 7.Kertzler JR, Richardson AB (1989) Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med 17:453–458 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Lee J, Brookenthal Kr, Ramsey ML, Kneeland JB, Herzog R (2000) MR imaging assessment of the pectoralis major myotendinous unit: an MR imaging-anatomic correlative study with surgical correlation. AJR Am Roentgenol 174(5):1371–1375 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lettenneur M (1861) Rupture sous-cutanie muscle grand pectoral. Inf Section Med J 52:202–205

- 10.Liu J, Wu J, Chang C, Chou Y, Lo W (1992) Avulsion of the pectoralis major tendon. Am J Sports Med 20:366–368 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Manjarris J, Gershuni DH, Moitoza J (1985) Rupture of the pectoralis major tendon. J Trauma 25:810–811 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.McEntire JE, Hess WE, Coleman SS (1972) Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 54:1040 [PubMed]

- 13.O’Donoghue DH (1976) Treatment of injuries to athletes. 3rd edn, Saunders, Philadelphia

- 14.Ohashi K, El-Khoury GY, Albright JP, Tearse DS (1996) MRI of complete rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Skeletal Radiol 25(7):625–628 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Park JY, Espinella JL (1970) Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle: A case report and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg 52A:577–581 [PubMed]

- 16.Patissier P (1882) Traite des maladies des artisans. Paris 162–164

- 17.Pimpalnerkar A, Datta A, Longhino D, Mohtadi N (2004) An unusual complication of Kocher’s manoeuvre. BMJ 329:1472–1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Travis RD, Doane R, Burkhead WZ Jr (2000) Tendon ruptures about the shoulder. Orthoped Clin North Am 31:313–330 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Wolfe SW, Wickiewicz TL, Cavanaugh JT (1992) Ruptures of the pectoralis major muscle. An anatomic and clinical analysis. Am J Sports Med 20:587–593 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Zeman S, Rosenfeld R, Lipscomb P (1979) Tears of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med 7(6):343–347 [DOI] [PubMed]