Abstract

Direct intraosseous injection of fibrosing agent is widely used in the treatment of aneurysmal bone cysts. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the consequences of fibrosing agent penetrating the medulla of bones. This may be the case when, by mistake, the fibrosing agent is administered into the medulla or when the wall of the cyst ruptures and fibrosing agent is able to drift into the medulla. Twelve rabbits were injected transcutaneously with a fibrosing agent directly into the proximal metaphysis of the tibia. Prior to injection 0.5 ml of liquid-like, bloody, intraosseal tissue was aspirated, then 0.5 ml of fibrosing agent was administered. Fibrosing agent was introduced slowly (20 s) to avoid overpressure. Nine rabbits (75%) died within minutes after the introduction of fibrosing agent. A full body roentgenogram was taken of each rabbit and the animals that died underwent autopsy to find the exact cause of death. Roentgenograms of the chest showed massive multiple pulmonary emboli confirmed in all lethal cases by the autopsy. This animal model was created to draw attention to the dangers of any leakage of the fibrosing agent into the medulla of bones.

Résumé

L’injection directe d’un agent fibrosant est largement utilisée dans le traitement des kystes anévrysmaux. Le but de cette étude était d’évaluer les conséquences de la diffusion de cet agent dans la médullaire car cela peut être le cas par erreur lors de l’injection directe ou si la paroi du kyste se rompt. Une injection per-cutanée de 0,5 ml d’agent fibrosant a été faite dans la métaphyse tibiale de 12 rats après ponction de 0,5 ml de liquide médullaire. L’injection a été faite lentement (20 secondes) pour éviter la surpression. 9 rats (75%) étaient perdus dans les minutes suivant l’injection. Des radiographies du corps entier faites sur tous les rats ainsi que l’autopsie de ceux qui étaient morts ont montrées des embolies pulmonaires multiples comme cause de décés. Ce modèle animal a été crée pour montrer les dangers du passage d’un agent fibrosant dans la médullaire osseuse.

Introduction

Aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) was recognised and described as a distinct clinicopathological entity by Jaffe and Lichtenstein in 1942 [9]. ABCs are benign lesions that consist of blood-filled spaces of variable size and are seen, most frequently, in teenagers [7]. The most common sites are the metaphysis of the long bones and the spine [7]. ABCs may be primary or secondary to an underlying lesion, such as fibrous dysplasia, chondroblastoma, giant cell tumour, or osteosarcoma [4]. Therefore, diagnosis must be based on typical radiological appearance and histopathological evidence [3]. After traditional surgical procedures (curettage and grafting) the local recurrence rate is about 11.8–30.8% [12]. Percutaneous procedures, such as direct injection of fibrosing agent (Ethibloc), have been reported with good results in ABCs [1, 2, 5–7]. However, other papers have reported some major local and general complications, such as pulmonary and vertebrobasilar embolisation, leakage of fibrosing agent in soft tissue, aseptic fistulisation and bone destruction [8, 10, 14].

Materials and methods

All animal procedures conformed to national regulations, and approval by the Ethics Committee was obtained. Twelve New Zealand White Rabbits underwent exactly the same procedures, and an additional three New Zealand White Rabbits served as a control group. The animals weighed between 2.1 kg and 2.7 kg each and were aged between 22 weeks and 26 weeks. None of the animals had any previously known affliction.

Prior to the injections, anaesthesia was administered (25 mg of ketamine hydrochloride and 0.5 mg medetomidin for every kilogramme of body weight through a cannula in the vena cephalica antebrachii). One hundred per cent oxygen was given through a mask, and oxygen saturation was controlled throughout the procedures. The left hind limb of the rabbit was shaved, isolated and was injected by a sterile surgical technique. The puncture was performed with a standard needle transcutaneously into the proximal metaphysis, reached through the medial cortex of the tibia, and 0.5 ml of liquid-like, bloody intraosseous tissue was aspirated to verify the correct location of the needle. Proceeding slowly (approximately 20 s) we injected 0.5 ml Ethibloc (Johnson & Johnson Hungary, Törökbálint, Hungary). Three additional rabbits, serving as a control group, underwent the same procedures except the final step, where the aspirated 0.5 ml liquid-like intraosseous tissue was re -administered instead of Ethibloc. In four hind limbs of two additional rabbits 0.5 ml of contrast material was injected into the medulla at the same injection site, while in four hind limbs of two other rabbits, the contrast material was injected into the distal metaphysis of the femur. In the cases where contrast material was injected we performed digital subtraction angiography in order to visualise any venous drainage.

All rabbits underwent postoperative full-body X-ray examination. The rabbits that died also underwent circumstantial autopsy by a team of human and veterinary pathologists. Segments of lung were conserved in formaldehyde. Slices of the lung tissue were stained by haematoxylin and eosin for histological evaluation.

Results

All seven rabbits not treated with Ethibloc (control group, rabbits injected with contrast material) recovered fully after anaesthesia and remained healthy during the follow-up period of 8 weeks. Nine of 12 animals (75%) treated with Ethibloc died within 3 to 15 min after the injection. One animal, also treated with Ethibloc, died one hour after being given the injection. Two animals treated with Ethibloc recovered fully from anaesthesia and remained healthy during the follow-up period of 8 weeks.

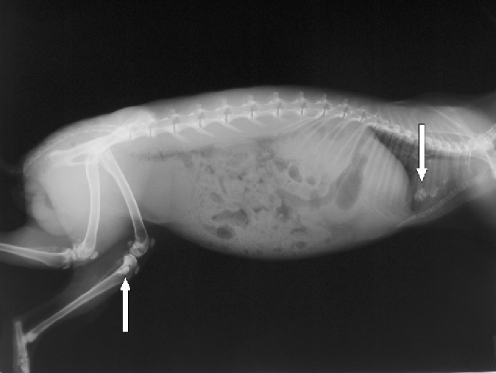

On the roentgenograms of injected tibias of all rabbits treated with Ethibloc, the fibrosing agent is well visible in the proximal metaphysis of the tibia (Fig. 1). In two rabbits (17%), leakage of fibrosing agent into subcutaneous tissue is also visible. On the roentgenograms of the ten rabbits that died after being given the injection, pulmonary embolisation was obvious in three cases (Fig. 1). However, the detailed full-body autopsy and a circumstantial autopsy of the lungs by a team of human and veterinary pathologists proved massive pulmonary embolism in ten of ten dissected animals. The affected pulmonary arteries contained emboli consisting solely of fibrosing agent (Ethibloc) and never of bone marrow or fatty tissue particles (Fig. 2). On two roentgenograms popliteal veins are well visible due to the presence of Ethibloc (Fig. 3). The histological evaluation of the slices of lung tissue ruled out the possibility of embolism caused by intraosseal fatty tissue, as the emboli contained neither cells nor matrix (Fig. 4). Thus, we concluded that all the dead animals had died of pulmonary Ethibloc embolisation.

Fig. 1.

Full-body roentgenogram shows fibrosing agent in the proximal metaphysis of the tibia and in the lungs at the same time

Fig. 2.

Macroscopic picture: lung segments were conserved in formaldehyde. On the slice of lung tissue, round, whitish-yellow, gelatinous emboli of fibrosing agent are obstructing pulmonary artery branches

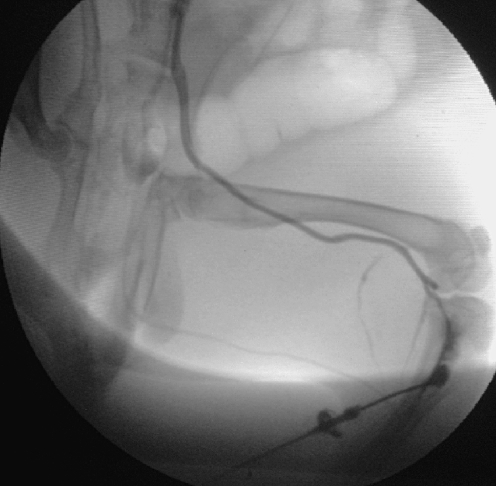

Fig. 3.

Popliteal veins are well visible due to the presence of fibrosing agent

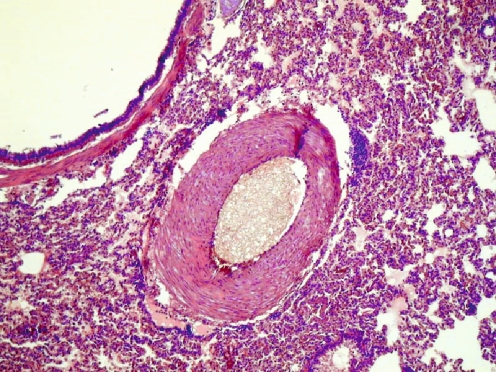

Fig. 4.

Microscopic picture: branch of the pulmonary artery is obstructed by embolus of fibrosing agent. Neither matrix nor cells are seen within the embolus. Surrounding lung tissue is intact; neither bleeding nor infarction is seen due to the acute character of death

Contrast material injected into the bone marrow behaved as if it were administered into a large vein. In a matter of 0.2–0.3 s contrast material drifted into the vena cava inferior. It is not through a special anastomosis of veins, specific to the tibia of rabbits, but the highly vascularised medulla of bone through which contrast material reaches the systematic circulation (Fig. 5). This should be no surprise if we think of the effectiveness of intraosseous volume therapy.

Fig. 5.

Contrast material injection into the proximal metaphysis of the tibia. Contrast material reaches the systematic circulation through the medulla of the bone

Discussion

Since the report by Szendrõi et al. in 1998, we have known that haemodynamic disturbance is on the venous side of the cysts, presenting itself in high intracystic pressure and the appearance of dilated, undulating veins [13], so much so that this disturbance is presumably the trigger point for cyst formation in the majority of ABCs [13]. It has been well documented that the ABCs’ drainage to veins plays a central role in general complications, such as embolism [11]. Owing to this fact, the injection of contrast material prior to the injection of Ethibloc is required to verify the absence of venous drainage [11, 14]. In spite of the effort to rule out such drainage, Topouchian et al., in 2004, reported a case of human pulmonary embolism of fibrosing agent that occurred after Ethibloc injection into a 15-year-old patient with an iliac ABC [14]. Similarly, Guibaud et al. reported a case of pulmonary embolism in spite of the cystograms that were taken and the fact that two high-risk patients with marked venous drainage were excluded from the study and were not treated with Ethibloc [8]. Peraud et al. reported a case of fatal embolisation of the vertebrobasilar system following percutaneous injection of Ethibloc into an ABC of the second cervical vertebra in a 4-year-old boy [10]. In these cases we believe that Ethibloc may have reached the systematic circulation by escaping from the damaged cyst and entering the medulla and then drifted into the systematic circulation.

The papers mentioned above show that, though the mapping of venous drainage and exclusion of high-risk patients can reduce the chances of embolism, the severe, sometimes lethal complications can not be avoided. The reason is that fibrosing agent may well drift into the systematic circulation not only through anastomosis of veins but also through the medulla itself. If the walls of small vessels in the cyst rupture during the introduction of Ethibloc, or if by mistake the fibrosing agent is administered directly into the medulla, the likelihood of embolisation will significantly increase, as shown in this study. Embolisation may, therefore, be the consequence of overpressure or overdose of the fibrosing agent.

Therefore, we conclude that, though the mapping of any venous drainage by injection of contrast material is an absolute necessity before the administration of fibrosing agent, the repeated administration of smaller quantities of Ethibloc may be safer than a single injection of a larger quantity.

References

- 1.Adamsbaum C, Kalifa G, Seringe R, Dubousset J (1993) Direct Ethibloc injection in benign bone cysts: preliminary report on four patients. Skeletal Radiol 22:317–320 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Adamsbaum C, Mascard E, Guinebretiere JM, Kalifa G, Dubousset J (2003) Intralesional Ethibloc injections in primary aneurysmal bone cysts: an efficient and safe treatment. Skeletal Radiol 32:559–566 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bollini G, Jouve JL, Cottalorda J, Petit P, Panuel M, Jacquemier M (1998) Aneurysmal bone cyst in children: analysis of twenty-seven patients. J Pediatr Orthop B 7:724–285 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bonakdarpour A, Levy WM, Aegerter E (1978) Primary and secondary aneurysmal cyst: a radiological study of 75 cases. Radiology 126:75–83 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dubois J, Chigot V, Grimard G, Isler M, Garel L (2003) Sclerotherapy in aneurysmal bone cysts in children: a review of 17 cases. Pediatr Radiol 33:365–372 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Falappa P, Fassari FM, Fanelli A, et al (2002) Aneurysmal bone cysts: treatment with direct percutaneous Ethibloc injection—long-term results. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 25:282–290 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Garg NK, Carty H, Walsh HPJ, Dorgan JC, Bruce CE (2000) Percutaneous Ethibloc injection in aneurysmal bone cyst. Skeletal Radiol 29:211–216 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Guibaud L, Herbetreau D, Dubois J, Stempfle N, Berard J, Pracros JP, Merland JJ (1998) Aneurysmal bone cysts: percutaneous embolization with an alcoholic solution of zein —series of 18 cases. Radiology 208:369–373 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L (1942) Solitary unicameral in aneurysmal bone cyst with emphasis on the Roentgen picture, pathologic appearance and pathogenesis. Arch Surg 44:1004–1007

- 10.Peraud A, Drake JM, Armstrong D, Hedden D, Babyn P, Wilson G (2004) Fatal Ethibloc embolisation of vertebrobasilar system following percutaneous injection into aneurysmal bone cyst of the second cervical vertebra. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 25:1116–1120 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Puig S, Aref H, Chigot V, Bonin B, Brunelle F (2003) Classification of venous malformations in children and implications for sclerotherapy. Pediatr Radiol 33:99–103 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Schreuder HW, Veth RP, Pruszczynski M, Lemmens JA, Koops HS, Molenaar WM (1997) Aneurysmal bone cysts treated by curettage, cryotherapy and bone grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Br 79:20–25 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Szendrõi M, Arató G, Ezzati A, Hüttl K, Szavcsur P (1998) Aneurysmal bone cyst: its pathogenesis based on angiographic, immunohistochemical and electron microscopic studies. Pathol Oncol Res 4:277–281 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Topouchian V, Mazda K, Hamze B, Laredo JD, Pennecot GF (2004) Aneurysmal bone cyst in children: complications of fibrosing agent injection. Radiology 232:522–526 [DOI] [PubMed]