Abstract

Numerous variations of intramedullary nails have been devised to achieve a stable fixation and early mobilisation of pertrochanteric fracture, among which is the proximal femoral nail (PFN). We report here the results of a prospective study carried out at our institute on 100 consecutive patients who had suffered a pertrochanteric, intertrochanteric or high subtrochanteric fracture, or a combination of fractures, between December 2002 and December 2005 and were subsequently treated with a PFN. Close to anatomical reduction of the fracture fragments was achieved in 12 patients, while limited open reduction was required in 14 patients. During the follow-up period of 1 year complications occurred in 12 patients. Our results indicate the necessity of a careful surgical technique and modifications that are specific to the individual fracture pattern in order to reduce complications. Osteosynthesis with the PFN offers the advantages of high rotational stability of the head-neck fragment, an unreamed implantation technique and the possibility of static or dynamic distal locking.

Résumé

Pour obtenir une fixation stable permettant une mobilisation précoce de nombreux clou intra-médullaires ont été conçus. Le clou proposé par le groupe AO/ASIF en 1996 permet la fixation des fractures per, inter ou sous trochantériennes. Nous avons fait une étude prospective de 100 patients consécutifs ayant une fracture d’un de ces types ou une combinaison d’un de ces types entre decembre 2002 et decembre 2005 et traité par un clou fémoral proximal. La réduction était anatomique chez 86 patients et chez 14 patients un abord limité était nécessaire pour la réduction. Pendant la période de suivi de 1 an, 12 patients avaient des complications.. Nous recommandons une technique chirurgicale précise et adaptée à la fracture.L’ostéosynthèse avec ce clou donne l’avantage de la stabilité rotatoire, n’oblige pas à un alésage et permet un verrouillage distal statique ou dynamique.

Introduction

The incidence of pertrochanteric fracture has increased significantly during recent years due to the advancing age of the world’s population [5, 6]. Numerous variations of intramedullary nails have been devised to achieve a stable fixation and early mobilisation of pertrochanteric fractures, among these the proximal femoral nail (PFN) devised by the AO/ASIF group in 1996 has proven to be a promising implant in per-, inter- or subtrochanteric femoral fractures.

We report here the results of a prospective study carried out at our institute on 100 consecutive patients who had suffered a pertrochanteric, intertrochanteric or high subtrochanteric fracture, or a combination of fractures, between December 2002 and December 2005 and were treated with a PFN.

Materials and methods

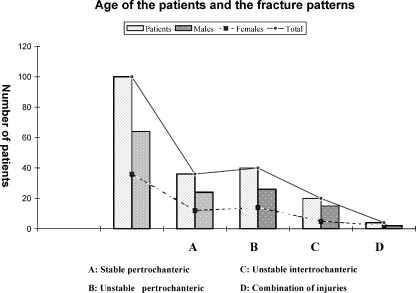

From December 2002 to December 2005 we treated 100 patients with stable and unstable proximal extra-capsular femoral fractures with a PFN. The mean age of the patients was 69 years (range: 33–82 years) and the sex distribution was 62 males and 36 females (Table 1). In 75% of the patients the fracture was the result of a domestic fall; in the remaining 25%, it was caused by a vehicular accident.

Table 1.

Type and distribution of proximal extra-capsular femoral fracture in the study cohort

| Type of fracture | Patients (n=100) | Males (n=64) | Females (n=36) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable pertrochanteric | 36 | 24 | 12 |

| Unstable pertrochanteric | 40 | 26 | 14 |

| Unstable intertrochanteric | 20 | 15 | 5 |

| Combination of injuries | 4 | 2 | 2 |

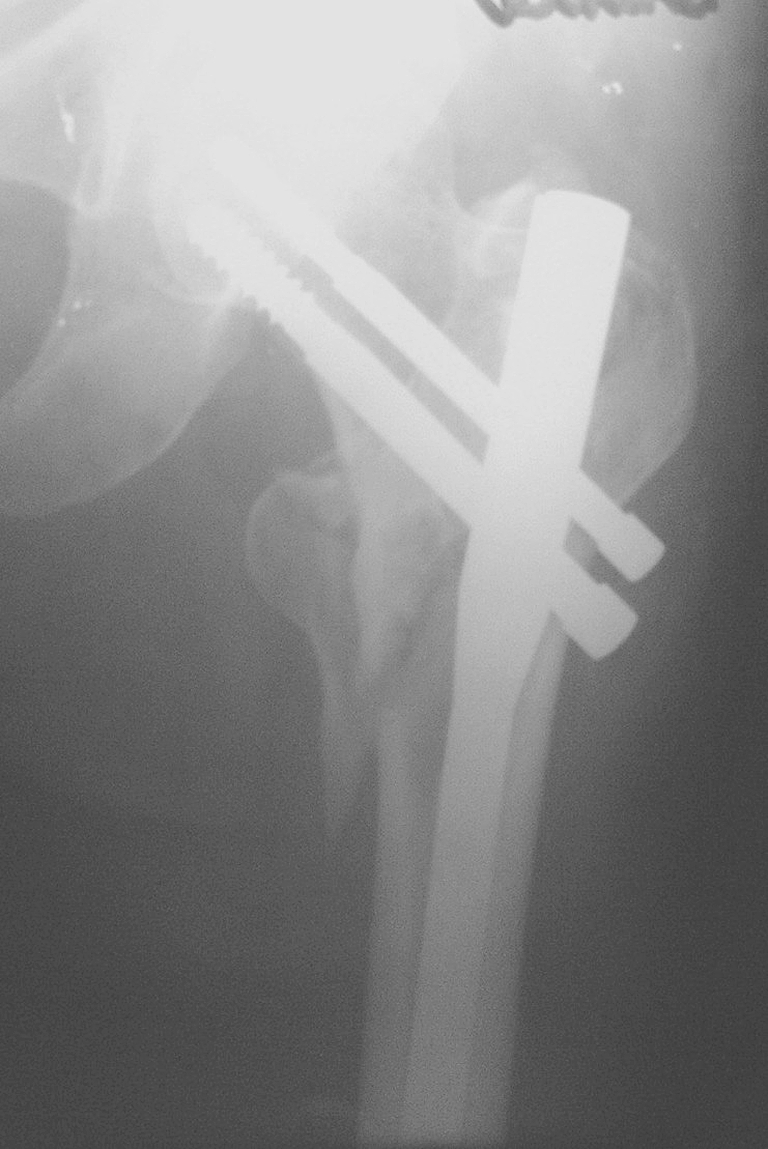

In accordance with the recommendations of the AO/ASIF, the preoperative radiographs were classified as 36-A1(stable pertrochanteric), 40-A2 (unstable pertrochanteric) (Figs. 1, 2, 3), 20-A3 (unstable intertrochanteric) (Figs. 4, 5), while four patients had a combination of injuries (Table 2). Surgery was performed within 48 h on a standard operation table. The patients were maintained on traction preoperatively. All operations were performed under spinal anaesthesia. Closed reduction was carried out and monitored by image intensifier on the anteroposterior and lateral views. A 5-cm incision was initially made from the cranial part of the greater trochanter, and a guide wire was passed through the trochanter distally, followed by trochanteric reaming over the guide wire. The nail (length: 250 mm; size: 9–12 mm; proximal portion: 15 mm) was implanted manually to suit the Indian femora. The 8.0-mm cervical screw and the 6.4-mm stabilising screw were introduced after the position of the guide wires had been confirmed and then assembled on the aiming device on the antero-posterior and lateral views. Depending upon the fracture configuration and stability, the distal static and dynamic holes were then locked.

Fig. 1.

Unstable A2 fracture

Fig. 2.

The A2 fracture at the 4-month follow up (healing)

Fig. 3.

Consolidation of the A2 fracture at the 8-month follow up

Fig. 4.

Unstable A3 fracture

Fig. 5.

Unstable A3 fracture showing good union

Table 2.

Distribution of the patients with respect to fracture pattern

Fractures in 86 patients were reduced by closed means, whereas 14 patients needed limited open reduction. The mean duration for the operation was 45 min (range: 32–95 min). Active and passive exercises were initiated within 48 h of operation. Partial weight bearing was allowed in 64 patients after suture removal, and 36 patients were confined to mobilisation in bed. A blood transfusion was needed for three patients who had a very low preoperative haemoglobin level.

Results

Postoperative radiographs showed a near-anatomical fracture reduction in 88% of patients. The patients were followed up at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months (average: 12 months). The fracture consolidated in 4.5 months. The greater trochanter was splintered and widened in 10% of the cases but eventually consolidated. No perceptible shortening was noted. Of the patients, 7% had superficial infections which were controlled with antibiotics, 82% had a full range of hip motion. Six patients died due to unrelated medical conditions within 15 months of the follow up, and six patients were lost to follow up after 8 months. We had a non-union in one case which was due to the primary distraction in a high subtrochanteric fracture (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Non-union in a high subtrochanteric fracture

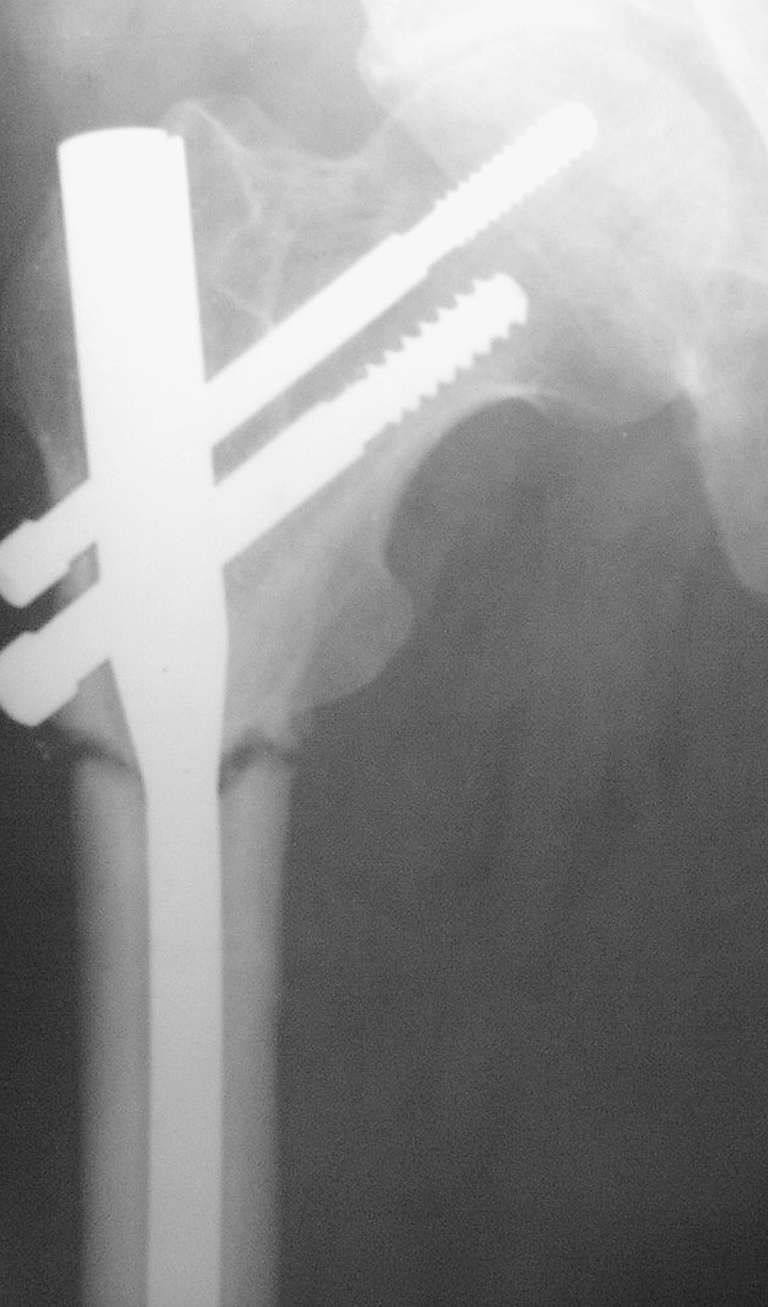

Migration of the screws due to severe osteoporosis was detected during the follow up in seven patients ( Fig. 7). In three of our patients we could see the ‘Z effect’ with the migration of hip pins into the joint . In one patient there was ectopic new bone formation at the insertion point of the stabilising and compression screw, but this that did not affect the patient’s condition. No cases of implant failure were observed.

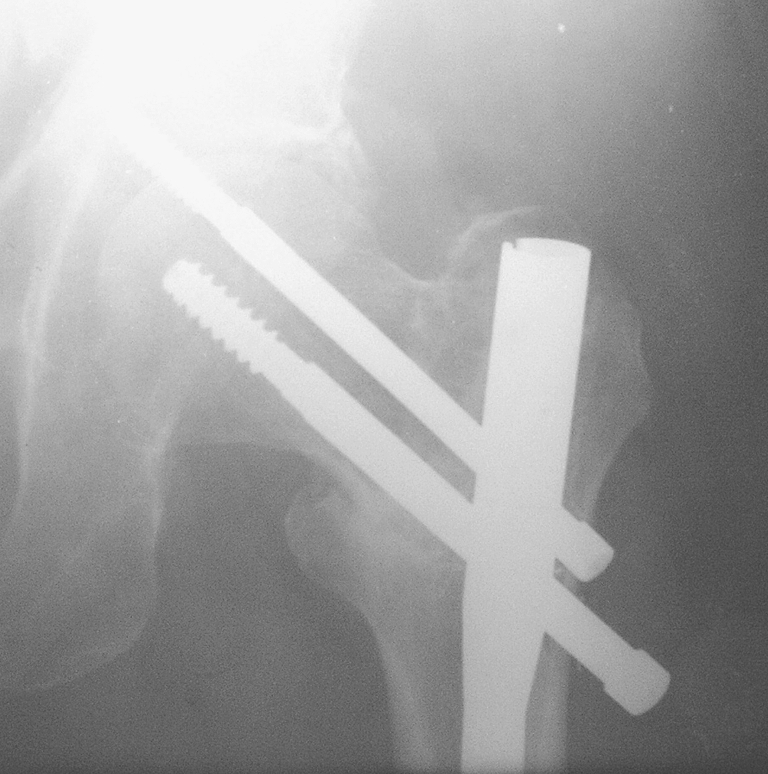

Fig. 7.

Screw penetration showing the ‘Z effect’

Discussion

The successful treatment of intertrochanteric fractures depends on many factors: the age of the patient, the patient’s general health, the time from fracture to treatment, the adequacy of treatment, concurrent medical treatment, the adequacy of treatment and the stability of fixation [3]. The appropriate method and the ideal implant by which to fix pertrochanteric fractures are topics still open to debate with proponents of the various approaches each claiming advantages over the other methods. Many internal fixation devices have been recommended for the treatment of pertrochanteric fractures, including extramedullary and intramedullary implants. The dynamic hip screw (DHS), initially introduced by Clawson in 1964, remains the implant of choice because of its favourable results and low rate of non-union and failure. It provides controlled compression at the fracture site.

The use of DHS has been supported by its biomechanical properties which have been assumed to improve the healing of fractures [9]. DHS requires a relatively larger exposure, more tissue handling and anatomical reduction, all of which increase the morbidity, the probability of infection and significant blood loss, the possibility of varus collapse and the inability of the implant to survive until fracture union. The side plate and screws weaken the bone mechanically. The common causes of fixation failure are instability of the fractures, osteoporosis, lack of anatomical reduction, failure of the fixation device and incorrect placement of the lag screw in femoral head [2, 7].

Control of axial telescoping and rotational stability are essential in unstable proximal femoral fractures. An intramedullary implant inserted in a minimally invasive manner is better tolerated in the elderly [13]

The cephalomedullary femoral reconstruction nails with a trochanteric entry point have gained popularity in recent years [14]. They have been shown to be biomechanically stronger than extramedullary implants.

The Gamma nail is associated with specific complications [12], among which is anterior thigh pain and fracture of the femoral shaft [4].

Intramedullary implants for internal fixation of the proximal femur withstand higher static and a several-fold higher cyclical loading than DHS types of implants. As a result, the fracture heals without the primary restoration of the medial support. The implant temporarily compensates for the function of the medial column [10].

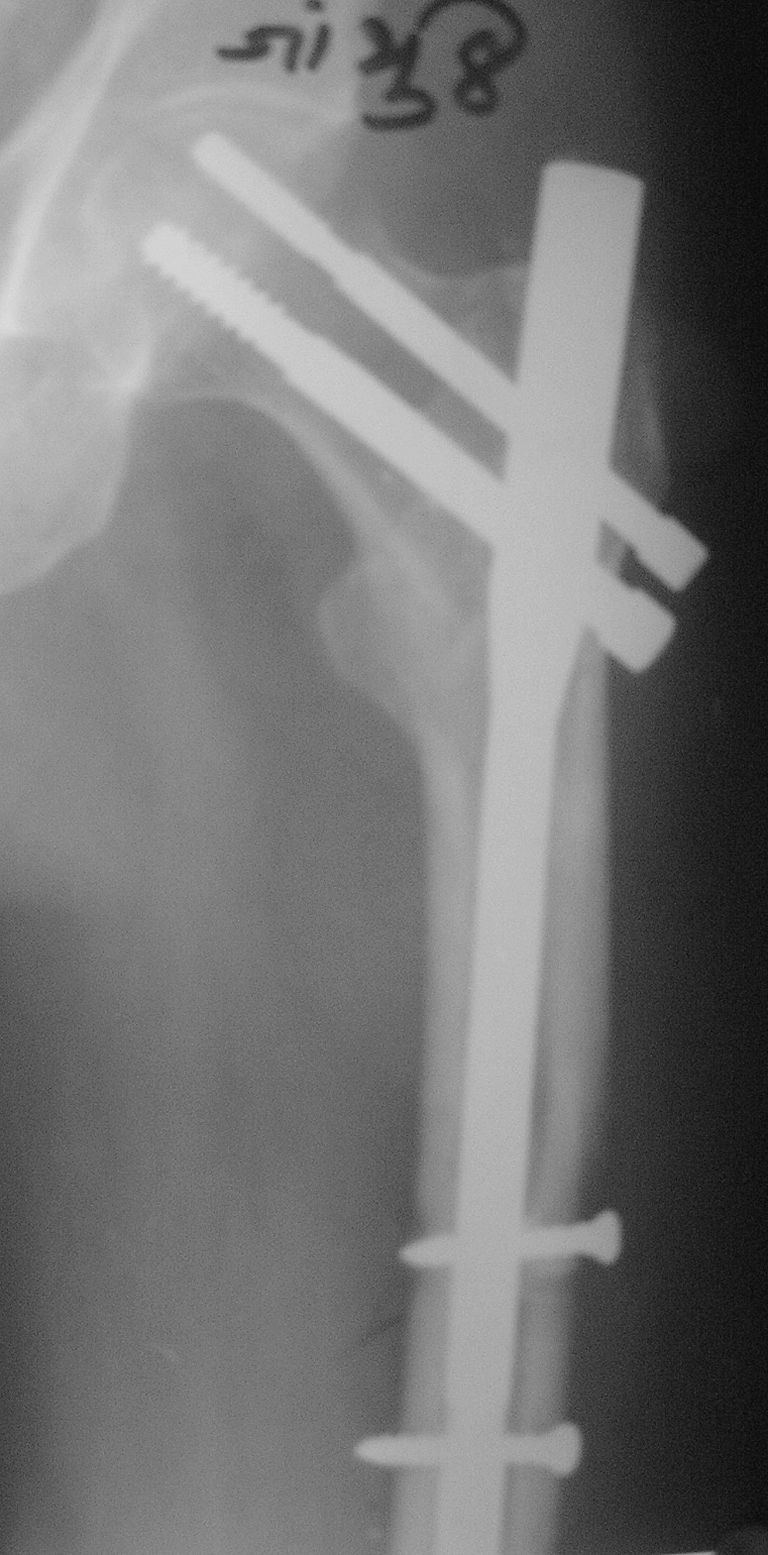

In A1 and A2 fractures axial loading leads to fracture impaction, whereas in A3 fractures such impaction does not occur, and medial displacement of the distal fragment of the fracture is common due to the instability. We have found the PFN to have superior results in A3 fractures in our series of 20 patients with this type of fracture (Figs. 8, 9).

Fig. 8.

An unstable A3 fracture

Fig. 9.

Unstable A3 fracture showing good union at the 9-month follow up

The PFN nail has been shown to prevent the fractures of the femoral shaft by having a smaller distal shaft diameter which reduces stress concentration at the tip [11]. Due to its position close to the weight-bearing axis the stress generated on the intramedullary implants is negligible. The PFN implant also acts as a buttress in preventing the medialisation of the shaft. The entry portal of the PFN through the trochanter limits the surgical insult to the tendinous hip abductor musculature only [8], unlike those nails which require entry through the pyriformis fossa [1]. The stabilising and the compression screws of the PFN adequately compress the fracture, leaving between them a bone block for further revision should the need arise. Our results corroborate those reported by Pajarinen et al. [9] that the use of PFN in the treatment of pertrochanteric fractures may have positive effect on the speed at which walking is restored. We partly base this conclusion on the fact that the six patients we lost during follow up all came from rural India.

In the series of 295 patients with trochanteric fractures treated with the PFN by Domingo et al. [15] the average age of the patients was 80 years, which possibly accounted for 27% of the patients who developed complications in the immediate postoperative period. We agree with these authors that the surgical technique is not complex, the number of complications recorded was acceptable and the overall results obtained are comparable with other fracture systems. We would like to stress that the low rates of femoral shaft fractures and fixation failure suggest that the PFN is useful for treating stable and unstable trochanteric fractures.

References

- 1.Ansari Moein CM, Verhofstad MHJ, Bleys RLAW, Werken C van der (2005) Soft tissue injury related to the choice of entry point in ante grade femoral nailing; pyriform fossa or greater trochanter tip. Injury 36:1337–1342 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Curtis MJ, Jinnh RH, Wilson V, Cunningham BW (1994) Proximal femoral fractures; a biomechanical study to compare extramedullary and intramedullary fixation. Injury 25:99–104 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Dean GL, David S, Jason HN (2004) Osteoporotic pertrochateric fractures; management and concurrent controversies. J Bone Jt Surg (Am) 72-B:737–752

- 4.Dousa P, Bartonicek J, Jehlicka D, Skala-Rosenbaum J (2002) Osteosynthesis of trochanteric fracture using proximal femoral nail. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 69:22–30 [PubMed]

- 5.Gulberg B, Duppe H, Nilsson B (1993) Incidence of Hip Fractures in Malmo, Sweden (1950–1991). Bone 14[Suppl 1]:23–29 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kannus P, Oarkkari J, Sievanen H et al (1996) Epidemiology of hip fractures. Bone 18[Suppl]:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kim WY, Han CH, Park JI, Kim FJY (2001) Failure of intertrochanteric fracture fixation with a dynamic hip screw in relation to preoperative fracture stability and osteoporosis. Int Orthop 25:360–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Menezes DF, Gamulin A, Noesberger B (2005) Is the proximal femoral nail a suitable implant for treatment of all trochanteric fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res 439:221–227 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Pajarinen J, Lindahl J, Michelsson O, Savolainen V, Hirvensalo E (1992) Pertrochanteric femoral fractures treated with a dynamic hip screw or a proximal femoral nail .J Bone Jt Surg (Br) 74-B:352–357 [PubMed]

- 10.Pavelka T, Matejka J, Cervenkova H (2005) Complications of internal fixation by a short proximal femoral nail. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 72:344–354 [PubMed]

- 11.Radford PJ, Needoff M, Webb JK (1993) A prospective randomized comparison of the dynamic hip screw and the gamma locking nail. J Bone Jt Surg (Br) 75-B:789–793 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Rosenblum SF, Zuckerman JD, Kummer FJ, Tam BS (1992) A biomechanical evaluation of Gamma Nail. J Bone Jt Surg 74:352–357 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Valverde JA, Alonso MG, Porro JG et al (1998) Use of Gamma nail in treatment of fractures of the proximal femur. Clin Orthop 350:56–61 [PubMed]

- 14.Windoff J, Hollander DA, Hakimi M, Linhart W (2005) Pitfalls and complications in the use of proximal femoral nail. Langenbecks Arch Surg 390(1):59–65, Feb Epub 2004 Apr 15 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Domingo LJ, Cecilia D, Herrera A, Resines C (2001) Trochanteric fractures treated with a proximal femoral nail. Int Orthop 25:298–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]