Abstract

The relatively recent discovery of miRNAs has added a completely new dimension to the study of the regulation of gene expression. The mechanism of action of miRNAs, the conservation between diverse species and the fact that each miRNA can regulate a number of targets and phenotypes clearly indicates the importance of these molecules. In this review the current state of knowledge relating to miRNA expression and gene regulation is presented, outlining the key morphological and biochemical features controlled by miRNAs with particular emphasis on the key phenotypes that impact on cell growth in bioreactors, namely proliferation and apoptosis.

Keywords: MiRNAs, Mammalian cell culture, Apoptosis, Proliferation

Introduction

Research into the regulation of gene expression through the action of miRNAs has increased exponentially over the last 3 years as demonstrated by the fact that in 2003 there were less than 100 miRNA papers cited in the Pubmed database (http://www.pubmed.gov), and already there are greater than 500 cited for 2006 (December). The importance of miRNAs lies in the broad range of phenotypes they regulate including development (Ambros 2003; Chen et al. 2004), cell proliferation and death (Brennecke et al. 2003), apoptosis and fat metabolism (Xu et al. 2003), cell differentiation (Chang et al. 2004) and a number of recent studies have identified miRNA profiles associated with diseases such as cancer (Volinia et al. 2006) and diabetes (Poy et al. 2004) hence it is clear that many of the phenotypes regulated by miRNAs are also of interest to the bioprocessing community. Currently there are modified CHO cell lines expressing genes to enhance apoptosis resistance (Crea et al. 2006; Choi et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2003; Lee and Lee 2003; Ifandi and Al-Rubeai 2005; Meents et al. 2002), CHO lines with engineered proliferation control (Fussenegger et al. 1997, 1998; Mazur et al. 1998, 1999; Ifandi and Al-Rubeai 2005; Bi et al. 2004; Carvalhal et al. 2003) and cells that have been engineered for improved metabolic phenotypes (Irani et al. 2002; Abston and Miller 2005). In certain cases cells have been “double engineered” to achieve both apoptosis resistance and controlled proliferation (Fussenegger et al. 1998; Ifandi and Al-Rubeai 2005), however over-engineering of cells has been linked to altered growth due to increased metabolic load (Yallop and Svendsen 2001; Yallop et al. 2003). Unlike many single gene manipulations, most miRNAs can regulate a number of gene targets (Bartel 2004), and the 3′UTRs (untranslated regions) of many genes contain putative binding sites for a number of miRNAs. Individual miRNAs such as miR-21 have been found to regulate more than one phenoytype including apoptosis and proliferation (Chan et al. 2005; Cheng et al. 2005). Currently there is no information on the expression of miRNAs in any hamster sub-types including Cricetulus griseus and none are listed in the Sanger miRNA repository of 4,361 known miRNAs. There are however a number of observations that implicate miRNAs in the regulation of CHO cell processes including the recent evidence that the cold shock protein Rbm3 increases global translation under conditions of mild hypothermia through inhibition of miRNA action (Dresios et al. 2005). Reduction of the culture temperature is a commonly applied but poorly understood strategy to increase the productivity, viability and stationary phase duration of production cell lines (Al-Fageeh et al. 2006; Fogolin et al. 2004; Furukawa and Ohsuye 1998; Kaufmann et al. 1999). miRNAs may also be responsible for the observed disconnects between microarray and proteomic CHO profiling data including the observation that although PDI, phosphoglycerate kinase and heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein were found upregulated upon reduction of culture temperature, the transcripts encoding these proteins were not significantly altered (Baik et al. 2006). More recently this laboratory has employed global miRNA profiling arrays to identify a number of differentially expressed miRNAs that correlate with both temperature and stage of suspension CHO culture (P. Gammell et al. in preparation). This aim of this review is to identify miRNAs regulating useful and industrially relevant phenotypes and present the mechanism of action where known.

Background to miRNA biology

Lin-4 was identified as the first miRNA in a genetic screen for mutants that disrupt post-embryonic development in Caenorhabditis elegans (Lee et al. 1993). It was found upon cloning of the Lin-4 locus, that Lin-4 produced a 22 nt non-coding RNA rather than a protein and that this RNA repressed the expression of Lin-14, a nuclear protein involved in the development of worms (Lee et al. 1993; Wightman et al. 1993). The action of Lin-4 required a high degree of homology between Lin-4 and sites in the 3′ UTR of Lin-14 (Ha et al. 1996; Olsen and Ambros 1999). In 2000 a second miRNA Let-7, was identified in C. elegans (Reinhart et al. 2000), which was demonstrated as having a similar function as Lin-4 (Reinhart et al. 2000; Slack et al. 2000; Lin et al. 2003). As a result of these and subsequent discoveries, miRNAs have been identified as a major class of evolutionarily conserved, highly abundant regulatory molecules. Currently there are 4,361 entries in the Sanger miRBase database (Release 9.0 October 2006 http://www.microrna.sanger.ac.uk/sequences/).

miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymersase II as long primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) (Cai et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2004). The pri-miRNA is cleaved at its flanks by Drosha, a nuclear ribonuclease III (RNaseIII) endonuclease, yielding stem loop structure of about 70 nt termed the precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) (Lee et al. 2002, 2003; Denli et al. 2004; Gregory et al. 2004; Han et al. 2004). Pre-miRNAs have 5′ phosphate and 3′ hydroxy termini and 2–3 nt 3′ single-stranded overhangs, these being characteristics of RNase III cleavage of dsRNA. Export of the pre-miRNA to the cytoplasm is facilitated by Exportin 5, which can recognize the specific end structure of miRNAs (Yi et al. 2003; Bohnsack et al. 2004; Lund et al. 2004; Zeng and Cullen 2004). On reaching the cytoplasm, Dicer, also an RNase III endonuclease, liberates the miRNA duplex (∼21 nt), and the mature miRNA strand of the miRNA duplex then enters the same RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) that is also used for the siRNA directed silencing pathway (Hutvagner and Zamore 2002). MiRNAs regulate target silencing using both target cleavage and translational repression. In plants it is more common to observe almost perfect homology between miRNA strands and the mRNA target, hence the RISC complex behaves as an endonuclease and cleaves the target mRNA between the target nucleotides paired to bases 10 and 11 of the miRNA. A number of mammalian miRNAs have also been demonstrated to cleave the target mRNAs also including miR-196 which can cleave HOXB8 mRNA in murine embryos and cell lines (Yekta et al. 2004). The normal situation for animal miRNAs however is that homology between the miRNA and the target mRNA is typically restricted to the 5′ end of the miRNA (Lewis et al. 2003, 2005; Brennecke et al. 2005). In this situation, the bound miRNA-RISC complex inhibits translation of the target mRNA either at the level of translational elongation or initiation of translation (Olsen and Ambros 1999; Pillai et al. 2005).

Despite the increasing number of identified and validated miRNA sequences currently available there is an almost complete lack of experimental evidence identifying the corresponding mRNA targets. A number of programs are available for the computational prediction of mRNA targets of miRNAs, however on average 200 genes, covering a range of gene categories are predicted to be regulated by each miRNA (reviewed by Krutzfeldt et al. 2006), which is a continuing challenge for miRNA research.

MiRNAs regulating cell growth and proliferation

Many of the discoveries relating miRNA expression to function have come from single miRNA inactivation approaches. Naturally, due to the small size of miRNAs this has been technically challenging, however a number of antisense-based approaches are available that transiently block miRNA function (Meister et al. 2004). A number of miRNAs regulating proliferation and growth have been identified through linkage with cancer phenotypes (reviewed by Esquela-Kershcer and Slack 2006), which is unsurprising as cancer is essentially a disease of uncontrolled proliferation.

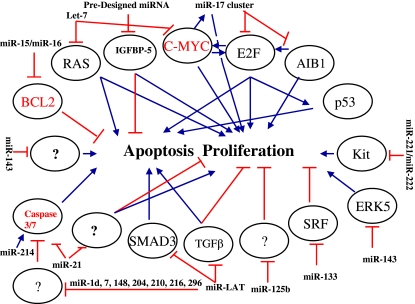

Growth control in bioreactors is crucial for efficient protein production and the use of biphasic culture strategies to control growth are commonly employed whereby cells are initially grown in conditions to promote high proliferation rates to maximize viable biomass and subsequently cell division is arrested (typically through reduction of the culture temperature), to encourage productivity and reduce apoptosis (Reviewed in Al-Fageeh et al. 2006; Butler 2005). A number of miRNAs have been identified that regulate the expression of proteins that control growth, including a number that have already been employed as targets for engineered proliferation control in CHO, these are presented here and summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Summary of miRNAs that regulate the expression of proteins that promote arrows or inhibit Tbars apoptosis and proliferation

The miRNAs encoding Lin-4 and Let-7 are known to control the timing of proliferation and differentiation in C. elegans and mutations can lead to uncontrolled growth and abnormalities. Although these are neamatode miRNAs, the level of conservation in miRNAs is extremely high and the complete sequence of mature Let-7 is conserved from worms to humans (Pasquinelli et al. 2000). The mammalian homologues of these genes also control proliferation in murine and human cells, inhibition of the miR-125b (Lin-4 homologue) resulted in reduced proliferation of human cancer cells (Lee et al. 2005), whereas Let-7 has been found to be a potent growth suppressor when expressed in DLD-1 colon cancer and A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells (Takamizawa et al. 2004; Akao et al. 2006). Let-7 represses RAS and C-MYC expression, and is greatly reduced in lung cancer facilitating high levels of RAS expression, hence it acts as a tumor suppressor in normal cells (Johnson et al. 2005; Akao et al. 2006). CHO cell lines have been separately engineered to overexpress C-MYC and RAS resulting in cells with increased growth rates and enhanced CMV product expression, respectively (Ifandi and Al-Rubeai 2005; Katakura et al. 1999; Miura et al. 2001). The use of C-MYC based approaches for the regulation of both proliferation and apoptosis is more complex than previously assumed following recent discoveries that although C-MYC induces the expression of the transcription factor E2F [essential for cell cycle progression and proliferation (Bracken et al. 2004)], and the expression of miR-17-5p and miR-20a, both of which are components of the miR-17 cluster [associated with cell proliferation (Hayashita et al. 2005)], miR-17-5p and miR-20a have been shown to negatively regulate E2F (O’Donnell et al. 2005). MiR-17-5p also inhibits the translation of amplified in breast cancer 1 (AIB1) resulting in reduced proliferation of breast cancer cell lines. The apparent tumor suppressor/growth enhancer effects of components of the miR-17 cluster seem to be dependant on both cell line and environment as the miR-17 cluster has also been linked to aggressive lymphomas and lung cancer, and has been shown to enhance lung cancer cell growth (Hayashita et al. 2005; He et al. 2005). Therefore MYC and its associated miRNA and mRNA targets are all components of a feedback loop complex presumably designed for tight control of cell proliferation under normal circumstances.

Two related miRNAs miR-143 and miR-145 have been found to suppress growth in human cell lines in a mechanism that it is at least partly due to regulation of ERK5, a known target of miR-143 (Esau et al. 2004). Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5) is a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family and, similar to ERK1/2. ERK5 is activated by growth factors and has an important role in the regulation of cell proliferation (Nishimoto and Nishida 2006). Other miRNAs that inhibit proliferation include miR-221 and miR-222 in CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs), via downregulation of Kit protein (Felli et al. 2005).

The use of cell cycle inhibitors in CHO cultures have been used to arrest growth as an alternative to mild hypothermia (Fusseneger et al. 1997; Bi et al. 2004; Mazur et al. 1999; Carvalhal et al. 2003). A number of miRNAs regulate proliferation via direct interference with cell cycle control including miR-372 and miR-373 which promote proliferation in human cell lines in a manner insensitive to increased levels of the inhibitor p21CIP1 essentially negating p53 mediated CDK inhibition (Voorhoeve et al. 2006). Both p21CIP1 and p27KIP1 have been used to regulate growth in CHO with noticeable improvements in specific productivity (Bi et al. 2004; Mazur et al. 1998; Fussenegger et al. 1997, 1998; Meents et al. 2002; Kaufman et al. 2001).

As an alternative to naturally occurring miRNAs, synthetic miRNA-like molecules can be generated against specific targets of choice. Transfection of specifically designed miRNAs against the 3′ UTR of IGFBP-5 were able to both decrease proliferation and induce apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells (Tanno et al. 2005).

Application of proliferation-related miRNAs to other cell types will require careful consideration as some of the effects can be cell line specific, i.e. the same miRNA may have very different effects depending on the cellular environment or context, in a specific example inhibition of miR-21 and miR-24 resulted in major increases in cell growth in HeLa but not A549 (Cheng et al. 2005), and expression of miR-21 increased proliferation in glioblastoma cell lines (Chan et al. 2005). It is likely that study of the tissue distribution profiles of miRNAs will help, i.e. ubiquitously expressed miRNAs having similar effects in many tissue types are likely to have similar effects when expressed in a range of cell lines, whereas tissue restricted miRNAs such as miR-133, the expression of which correlates with enhanced myoblast proliferation via repression of serum response factor (SRF), may be phenomenon associated with a particular tissue type, in this case skeletal muscle (Chen et al. 2006).

miRNA targets regulating apoptosis

Apoptosis or programmed cell death (PCD) is an obstacle to maintaining the high viable cell densities required to ensure long-term productivity in bioreactors (reviewed by Laken and Leonard 2001). Apoptosis in bioreactors is a result of a number of stressful conditions that emerge as a result of the production process, including nutrient limitation, mechanical agitation, oxygen depletion and waste accumulation (Al-Rubeai and Singh 1998). Cell death through apoptosis can have very negative effects on product quality and overall productivity (Fussenegger and Bailey 1998; Arden and Betenbaugh 2004), therefore a number of apoptosis intervention approaches have been employed to extend the viable lifespan of mammalian cells in culture and hence increase overall productivity.

Anti-apoptotic proteins including Bcl-2 and BclXl oppose the progression of apoptosis. These proteins inhibit apoptosis through the maintenance of mitochondrial membrane integrity and by binding to pro-apoptotic Bcl family members (Yang et al. 1997; Sun et al. 2002; Gross et al. 1999). As a result of this, the exogenous expression of Bcl-2 and BclXl have formed the basis for a number of apoptosis intervention strategies in CHO, hybridoma and NS0 cells. In general most researchers have observed increased maximum cell number, enhanced viability, extended culture duration, protection from viral and sodium butyrate mediated apoptosis and in certain cases increased titers following expression of Bcl family members. (Fassnacht et al. 1999; Tey et al. 2000; Goswami et al. 1999; Simpson et al. 1999; Fussenegger et al. 2000; Mastrangelo et al. 2000a, b; Meents et al. 2002; Chiang and Sisk 2005; Kim and Lee 2002; Sung and Lee 2005; Sauerwald et al. 2006; Ifandi and Al-Rubeai 2005). Viral homologues of Bcl-2 including E1B19K have also been used for the inhibition of apoptosis in mammalian cell cultures (Wong et al. 2006; Figueroa et al. 2006), where E1B19K inhibits the apoptotic activity of p53 (Debbas and White 1993; Lowe and Ruley 1993).

An early association of miRNAs with the regulation of with apoptosis came from a study of patients with chronic lymphotytic leukemia (CLL), in this study it was found that there was a correlation in the expression of Bcl-2 with the absence of miR-15 and miR-16 (Calin et al. 2002, 2004). Subsequent cell line experiments confirmed that miR-15 and 16 promote apoptosis through negative regulation of Bcl-2 at a post-translational level (Cimmino et al. 2005).

Viruses also subvert the cell suicide pathways via miRNA action, and a recently discovered miRNA encoded within the HSV-1 LAT gene, exerts its anti-apoptotic function in mammalian cells via downregulation of TGF-β1 and SMAD3 (Gupta et al. 2006). Regulation of TGF β1 translation can also be used to control cell growth as it is a potent growth inhibitor (Schuster and Krieglstein 2002) and experiments have shown that targeting the TGF β1 receptor in CHO cells can attenuate the growth inhibitory response to TGF β1 in wild-type CHO cells (Tseng et al. 2004).

MiR-21 is known to be upregulated in a number of cancers and as such is described as an oncogenic miRNA (Si et al. 2006; Roldo et al. 2006; Meng et al. 2006; Volinia et al. 2006; Iorio et al. 2005; Chan et al. 2005) and operates at least partly via the inhibition of apoptosis. Silencing of miR-21 in glioblastoma cells was observed to result in activation of caspase 3 and 7 and increased apoptosis across a panel of cell lines and resulted in much lower proliferation rates (Chan et al. 2005).

A number of other miRNAs have been implicated in the regulation of apoptosis including miR-278, de-regulated expression of this miRNA in Drospohila has been found to be responsible for massive overgrowth of developing eyes, through inhibition of apoptosis (Nairz et al. 2006) others include miR-1d, 7, 15, 16, 21, 148, 204, 210, 216, and 296 (Chan et al. 2005; Cheng et al. 2005) although the functional targets are unknown for most of these.

Conclusions and future prospects

The number of discoveries relating miRNA to cell growth and survival indicate that it will be important to relate these findings to industrially relevant cell lines including CHO. The improvements in the technology available to profile miRNA expression and the recent finding in this laboratory that these methods are suitable for use in CHO cultures (Gammell et al. in preparation) will accelerate this process.

References

- Abston LR, Miller WM (2005) Effects of NHE1 expression level on CHO cell responses to environmental stress. Biotechnol Prog 21:562–567 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Akao Y, Nakagawa Y, Naoe T (2006) let-7 microRNA functions as a potential growth suppressor in human colon cancer cells. Biol Pharm Bull 29:903–906 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Al-Fageeh MB, Marchant RJ, Carden MJ, Smales CM (2006) The cold-shock response in cultured mammalian cells: harnessing the response for the improvement of recombinant protein production. Biotechnol Bioeng 93:829–835 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Al-Rubeai M, Singh RP (1998) Apoptosis in cell culture. Curr Opin Biotechnol 9:152–156 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ambros V (2003) MicroRNA pathways in flies and worms: growth, death, fat, stress, and timing. Cell 113:673–676 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Arden N, Betenbaugh MJ (2004) Life and death in mammalian cell culture: strategies for apoptosis inhibition. Trends Biotechnol 22:174–180 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Baik JY, Lee MS, An SR, Yoon SK, Joo EJ, Kim YH, Park HW, Lee GM (2006) Initial transcriptome and proteome analyses of low culture temperature-induced expression in CHO cells producing erythropoietin. Biotechnol Bioeng 93:361–371 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116:281–297 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bi JX, Shuttleworth J, Al-Rubeai M (2004) Uncoupling of cell growth and proliferation results in enhancement of productivity in p21CIP1-arrested CHO cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 85:741–749 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bohnsack MT, Czaplinski K, Gorlich D (2004) Exportin 5 is a RanGTP-dependent dsRNA-binding protein that mediates nuclear export of pre-miRNAs. RNA 10:185–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bracken AP, Ciro M, Cocito A, Helin K (2004) E2F target genes: unraveling the biology. Trends Biochem Sci 29:409–417 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brennecke J, Hipfner DR, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM (2003) bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell 113:25–36 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM (2005) Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol 3:e85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Butler M (2005) Animal cell cultures: recent achievements and perspectives in the production of biopharmaceuticals. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 68:283–291 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cai X, Hagedorn CH, Cullen BR (2004) Human microRNAs are processed from capped, polyadenylated transcripts that can also function as mRNAs. RNA 10:1957–1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, Aldler H, Rattan S, Keating M, Rai K, Rassenti L, Kipps T, Negrini M, Bullrich F, Croce CM (2002) Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro-RNA genes mir15 and mir16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:15524–15529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Calin GA, Liu CG, Sevignani C, Ferracin M, Felli N, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Cimmino A, Zupo S, Dono M, Dell’Aquila ML, Alder H, Rassenti L, Kipps TJ, Bullrich F, Negrini M, Croce CM (2004) MicroRNA profiling reveals distinct signatures in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:11755–11760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carvalhal AV, Marcelino I, Carrondo MJT (2003) Metabolic changes during cell growth inhibition by p27 overexpression. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 63:164–173 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chan JA, Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS (2005) MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res 65:6029–6033 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chang S, Johnston RJ Jr, Frokjaer-Jensen C, Lockery S, Hobert O (2004) MicroRNAs act sequentially and asymmetrically to control chemosensory laterality in the nematode. Nature 430:785–789 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science 303:83–86 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, Conlon FL, Wang DZ (2006) The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet 38:228–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cheng AM, Byrom MW, Shelton J, Ford LP (2005) Antisense inhibition of human miRNAs and indications for an involvement of miRNA in cell growth and apoptosis. Nucleic Acids Res 33:1290–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chiang GG, Sisk WP (2005) Bcl-x(L) mediates increased production of humanized monoclonal antibodies in chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 91:779–792 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Choi SS, Rhee WJ, Kim EJ, Park TH (2006) Enhancement of recombinant protein production in chinese hamster ovary cells through anti-apoptosis engineering using 30Kc6 gene. Biotechnol Bioeng 95:459–467 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cimmino A, Calin GA, Fabbri M, Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE, Aqeilan RI, Zupo S, Dono M, Rassenti L, Alder H, Volinia S, Liu CG, Kipps TJ, Negrini M, Croce CM (2005) Mir-15 and mir-16 induce apoptosis by targeting BCL2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:13944–13949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Crea F, Sarti D, Falciani F, Al-Rubeai M (2006) Over-expression of hTERT in CHOK1 results in decreased apoptosis and reduced serum dependency. J Biotechnol 121:109–123 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Debbas M, White E (1993) Wild-type p53 mediates apoptosis by E1A, which is inhibited by E1B. Genes Dev 7:546–554 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Denli AM, Tops BB, Plasterk RH, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ (2004) Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature 432:231–235 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dresios J, Aschrafi A, Owens GC, Vanderklish PW, Edelman GM, Mauro VP (2005) Cold stress-induced protein Rbm3 binds 60S ribosomal subunits, alters microRNA levels, and enhances global protein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:1865–1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Esau C, Kang X, Peralta E, Hanson E, Marcusson EG, Ravichandran LV, Sun Y, Koo S, Perera RJ, Jain R, Dean NM, Freier SM, Bennett CF, Lollo B, Griffey R (2004) MicroRNA-143 regulates adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem 279:52361–52365 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ (2006) Oncomirs – microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 6:259–269 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fassnacht D, Rossing S, Singh RP, Al-Rubeai M, Portner R (1999) Influence of bcl-2 on antibody productivity in high cell density perfusion cultures of hybridoma. Cytotechnology 30:95–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Felli N, Fontana L, Pelosi E, Botta R, Bonci D, Facchiano F, Liuzzi F, Lulli V, Morsilli O, Santoro S, Valtieri M, Calin GA, Liu CG, Sorrentino A, Croce CM, Peschle C (2005) MicroRNAs 221 and 222 inhibit normal erythropoiesis and erythroleukemic cell growth via kit receptor down-modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:18081–18086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Figueroa B.Jr., Ailor E, Osbourne D, Hardwick JM, Reff M, Betenbaugh MJ (2006) Enhanced cell culture performance using inducible anti-apoptotic genes E1B-19K and Aven in the production of a monoclonal antibody with Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnol Bioeng Published online 10 Nov 2006 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fogolin MB, Wagner R, Etcheverrigaray M, Kratje R (2004) Impact of temperature reduction and expression of yeast pyruvate carboxylase on hGM-CSF-producing CHO cells. J Biotechnol 109:179–191 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Furukawa K, Ohsuye K (1998) Effect of culture temperature on a recombinant CHO cell line producing a C-terminal α-amidating enzyme. Cytotechnology 26:153–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fussenegger M, Bailey JE (1998) Molecular regulation of cell-cycle progression and apoptosis in mammalian cells: implications for biotechnology. Biotech Progress 14:807–833 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fussenegger M, Mazur X, Bailey JE (1997) A novel cytostatic process enhances the productivity of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 55:927–939 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fussenegger M, Schlatter S, Datwyler D, Mazur X, Bailey JE (1998) Controlled proliferation by multigene metabolic engineering enhances the productivity of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Nat Biotechnol 16:468–472 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fussenegger M, Fassnacht D, Schwartz R, Zanghi JA, Graf M, Bailey JE, Portner R (2000) Regulated overexpression of the survival factor bcl-2 in CHO cells increases viable cell density in batch culture and decreases DNA release in extended fixed-bed cultivation. Cytotechnology 32:45–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Goswami J, Sinskey AJ, Steller H, Stephanopoulos GN, Wang DIC (1999) Apoptosis in batch cultures of Chinese Hamster Ovary cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 62:632–640 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G, Chendrimada T, Doratotaj B, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R (2004) The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature 432:235–240 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ (1999) BCL-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev 13:1899–1911 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gupta A, Gartner JJ, Sethupathy P, Hatzigeorgiou AG, Fraser NW (2006) Anti-apoptotic function of a microrna encoded by the HSV-1 latency-associated transcript. Nature 442:82–85 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ha I, Wightman B, Ruvkun G (1996) A bulged lin-4/lin-14 RNA duplex is sufficient for Caenorhabditis elegans lin-14 temporal gradient formation. Genes Dev 10:3041–3050 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN (2004) The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev 18:3016–3027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hayashita Y, Osada H, Tatematsu Y, Yamada H, Yanagisawa K, Tomida S, Yatabe Y, Kawahara K, Sekido Y, Takahashi T (2005) A polycistronic microRNA cluster, miR-17-92, is overexpressed in human lung cancers and enhances cell proliferation. Cancer Res 65:9628–9632 [DOI] [PubMed]

- He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, Goodson S, Powers S, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW, Hannon GJ, Hammond SM (2005) A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature 435:828–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hutvagner G, Zamore PD (2002) A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex. Science 297:2056–2060 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ifandi V, Al-Rubeai M (2005) Regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis in CHO-K1 cells by the coexpression of c-Myc and Bcl-2. Biotechnol Prog 21:671–677 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Liu CG, Veronese A, Spizzo R, Sabbioni S, Magri E, Pedriali M, Fabbri M, Campiglio M, Menard S, Palazzo JP, Rosenberg A, Musiani P, Volinia S, Nenci I, Calin GA, Querzoli P, Negrini M, Croce CM (2005) Microrna gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer Res 65:7065–7070 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Irani N, Beccaria AJ, Wagner R (2002) Expression of recombinant cytoplasmic yeast pyruvate carboxylase for the improvement of the production of human erythropoietin by recombinant BHK-21 cells. J Biotechnol 93:269–282 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, Labourier E, Reinert KL, Brown D, Slack FJ (2005) RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell 120:635–647 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Katakura Y, Seto P, Miura T, Ohashi H, Teruya K, Shirahata S (1999) Productivity enhancement of recombinant protein in CHO cells via specific promoter activation by oncogenes. Cytotechnology 31:103–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann H, Mazur X, Fussenegger M, Bailey JE (1999) Influence of low temperature on productivity, proteome and protein phosphorylation of CHO cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 63:573–582 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann H, Mazur X, Marone R, Bailey JE, Fussenegger M (2001) Comparative analysis of two controlled proliferation strategies regarding product quality, influence on tetracycline-regulated gene expression, and productivity. Biotechnol Bioeng 72:592–602 [PubMed]

- Kim NS, Lee GM (2002) Response of recombinant Chinese hamster ovary cells to hyperosmotic pressure: effect of Bcl-2 overexpression. J Biotechnol 95:237–248 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim NS, Chang KH, Chung BS, Kim SH, Kim JH, Lee GM (2003) Characterization of humanized antibody produced by apoptosis-resistant CHO cells under sodium butyrate-induced condition. J Microbiol Biotechnol 13:926–936

- Krutzfeldt J, Poy MN, Stoffel M (2006) Strategies to determine the biological function of microRNAs. Nat Genet 38 Suppl:S14–S19 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Laken HA, Leonard MW (2001) Understanding and modulating apoptosis in industrial cell culture. Curr Opin Biotechnol 12:175–179 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee SK, Lee GM (2003) Development of apoptosis-resistant dihydrofolate reductase-deficient Chinese hamster ovary cell line. Biotechnol Bioeng 82:872–876 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V (1993) The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75:843–854 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee Y, Jeon K, Lee JT, Kim S, Kim VN (2002) MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J 21:4663–4670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Radmark O, Kim S, Kim VN (2003) The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature 425:415–419 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN (2004) MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J 23:4051–4060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee YS, Kim HK, Chung S, Kim KS, Dutta A (2005) Depletion of human micro-RNA miR-125b reveals that it is critical for the proliferation of differentiated cells but not for the down-regulation of putative targets during differentiation. J Biol Chem 280:16635–16641 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB (2003) Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell 115:787–798 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP (2005) Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lin SY, Johnson SM, Abraham M, Vella MC, Pasquinelli A, Gamberi C, Gottlieb E, Slack FJ (2003) The C elegans hunchback homolog, hbl-1, controls temporal patterning and is a probable microRNA target. Dev Cell 4:639–650 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lowe SW, Ruley HE (1993) Stabilization of the p53 tumor suppressor is induced by adenovirus 5 E1A and accompanies apoptosis. Genes Dev 7:535–545 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lund E, Guttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE, Kutay U (2004) Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science 303:95–98 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mastrangelo AJ, Hardwick JM, Bex F, Betenbaugh MJ (2000a) Part I. Bcl-2 and Bcl-x(L) limit apoptosis upon infection with alphavirus vectors. Biotechnol Bioeng 67:544–554 [PubMed]

- Mastrangelo AJ, Hardwick JM, Zou SF, Betenbaugh MJ (2000b) Part II. Overexpression of bcl-2 family members enhances survival of mammalian cells in response to various culture insults. Biotechnol Bioeng 67:555–564 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mazur X, Fussenegger M, Renner WA, Bailey JE (1998) Higher productivity of growth-arrested Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27. Biotechnol Prog 14:705–713 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mazur X, Eppenberger HM, Bailey JE, Fussenegger M (1999) A novel autoregulated proliferation-controlled production process using recombinant CHO cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 65:144–150 [PubMed]

- Meents H, Enenkel B, Eppenberger HM, Werner RG, Fussenegger M (2002) Impact of coexpression and coamplification of sICAM and antiapoptosis determinants bcl-2/bcl-x(L) on productivity, cell survival, and mitochondria number in CHO-DG44 grown in suspension and serum-free media. Biotech Bioeng 80:706–716 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Meister G, Landthaler M, Dorsett Y, Tuschl T (2004) Sequence-specific inhibition of microRNA- and siRNA-induced RNA silencing. RNA 10:544–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Meng F, Henson R, Lang M, Wehbe H, Maheshwari S, Mendell JT, Jiang J, Schmittgen TD, Patel T (2006) Involvement of human micro-RNA in growth and response to chemotherapy in human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. Gastroenterology 130:2113–2129 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miura T, Katakura Y, Seto P, Zhang YP, Teruya K, Nishimura E, Kato M, Hashizume S, Shirahata S (2001) Availability of oncogene activated production system for mass production of light chain of human antibody in CHO cells. Cytotechnology 35:9–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nairz K, Rottig C, Rintelen F, Zdobnov E, Moser M, Hafen E (2006) Overgrowth caused by misexpression of a microrna with dispensable wild-type function. Dev Biol 291:314–324 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nishimoto S, Nishida E (2006) MAPK signalling: ERK5 versus ERK1/2. EMBO Rep 7:782–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Mendell JT (2005) c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature 435:839–843 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Olsen PH, Ambros V (1999) The lin-4 regulatory RNA controls developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans by blocking LIN-14 protein synthesis after the initiation of translation. Dev Biol 216:671–680 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI, Maller B, Hayward DC, Ball EE, Degnan B, Muller P, Spring J, Srinivasan A, Fishman M, Finnerty J, Corbo J, Levine M, Leahy P, Davidson E, Ruvkun G (2000) Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature 408:86–89 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pillai RS, Bhattacharyya SN, Artus CG, Zoller T, Cougot N, Basyuk E, Bertrand E, Filipowicz W (2005) Inhibition of translational initiation by Let-7 MicroRNA in human cells. Science 309:1573–1576 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, Kuwajima S, Ma X, Macdonald PE, Pfeffer S, Tuschl T, Rajewsky N, Rorsman P, Stoffel M (2004) A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature 432:226–230 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G (2000) The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 403:901–906 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Roldo C, Missiaglia E, Hagan JP, Falconi M, Capelli P, Bersani S, Calin GA, Volinia S, Liu CG, Scarpa A, Croce CM (2006) Microrna expression abnormalities in pancreatic endocrine and acinar tumors are associated with distinctive pathologic features and clinical behavior. J Clin Oncol 24:4677–4684 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sauerwald TM, Figueroa B, Hardwick JM, Oyler GA, Betenbaugh MJ (2006) Combining caspase and mitochondrial dysfunction inhibitors of apoptosis to limit cell death in mammalian cell cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng 94:362–372 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schuster N, Krieglstein K (2002) Mechanisms of TGF-beta-mediated apoptosis. Cell Tissue Res 307:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Si ML, Zhu S, Wu H, Lu Z, Wu F, Mo YY (2006) Mir-21-mediated tumor growth. Oncogene Oct 30; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Simpson NH, Singh RP, Emery AN, Al-Rubeai M (1999) Bcl-2 over-expression reduces growth rate and prolongs G(1) phase in continuous chemostat cultures of hybridoma cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 64:174–186 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Slack FJ, Basson M, Liu Z, Ambros V, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G (2000) The lin-41 RBCC gene acts in the C. elegans heterochronic pathway between the let-7 regulatory RNA and the LIN-29 transcription factor. Mol Cell 5:659–669 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sun XM, Bratton SB, Butterworth M, Macfarlane M, Cohen GM (2002) Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl inhibit CD95-mediated apoptosis by preventing mitochondrial release of Smac/DIABLO and subsequent inactivation of X-linked inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein. J Biol Chem 277:11345–11351 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sung YH, Lee GM (2005) Enhanced human thrombopoietin production by sodium butyrate addition to serum-free suspension culture of Bcl-2-overexpressing CHO cells. Biotechnol Progr 21:50–57 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Takamizawa J, Konishi H, Yanagisawa K, Tomida S, Osada H, Endoh H, Harano T, Yatabe Y, Nagino M, Nimura Y, Mitsudomi T, Takahashi T (2004) Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Res 64:3753–3756 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tanno B, Cesi V, Vitali R, Sesti F, Giuffrida ML, Mancini C, Calabretta B, Raschella G (2005) Silencing of endogenous IGFBP-5 by micro RNA interference affects proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation of neuroblastoma cells. Cell Death Differ 12:213–223 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tey BT, Singh RP, Piredda L, Piacentini M, Al-Rubeai M (2000) Influence of Bcl-2 on cell death during the cultivation of a Chinese hamster ovary cell line expressing a chimeric antibody. Biotechnol Bioeng 68:31–43 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tseng WF, Huang SS, Huang JS (2004) LRP-1/T beta R-V mediates TGF-beta 1-induced growth inhibition in CHO cells. FEBS Lett 562:71–78 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, Prueitt RL, Yanaihara N, Lanza G, Scarpa A, Vecchione A, Negrini M, Harris CC, Croce CM (2006) A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:2257–2261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Voorhoeve PM, Le Sage C, Schrier M, Gillis AJ, Stoop H, Nagel R, Liu YP, van Duijse J, Drost J, Griekspoor A, Zlotorynski E, Yabuta N, De Vita G, Nojima H, Looijenga LH, Agami R (2006) A genetic screen implicates miRNA-372 and miRNA-373 as oncogenes in testicular germ cell tumors. Cell 124:1169–1181 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G (1993) Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 75:855–862 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wong DCF, Wong KTK, Nissom PM, Heng CK, Yap MGS (2006) Transcriptional profiling of apoptotic pathways in batch and fed-batch CHO cell cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng 94:373–382 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xu P, Vernooy SY, Guo M, Hay BA (2003) The Drosophila microRNA Mir-14 suppresses cell death and is required for normal fat metabolism. Curr Biol 13:790–795 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yallop C, Svendsen I (2001) The effects of G418 on the growth and metabolism of recombinant mammalian cell lines. Cytotechnology 35:101–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yallop C, Nørby PL, Jensen R, Reinbach H, Svendsen I (2003) Characterisation of G418-induced metabolic load in recombinant CHO and BHK cells: effect on the activity and expression of central metabolic enzymes. Cytotechnology 42:87–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Liu X, Bhalla K, Kim CN, Ibrado AM, Cai J, Peng TI, Jones DP, Wang X (1997) Prevention of apoptosis by Bcl-2: release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science 275:1129–1132 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yekta S, Shih IH, Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNA-directed cleavage of HOXB8 mRNA. Science 304:594–596 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR (2003) Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev 17:3011–3016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zeng Y, Cullen BR (2004) Structural requirements for pre-microRNA binding and nuclear export by Exportin 5. Nucleic Acids Res 32:4776–4785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]