Abstract

Tears of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in the skeletally immature patient are becoming more prevalent. The aim of this study was to describe the functional outcome and to evaluate the best management of total tears of the ACL in skeletally immature patient. Twenty consecutive, skeletally immature patients with a clinically evident rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament were followed up for a mean of 5.4 years. The mean age at the time of injury was 13.9 years old. The study group consisted of 13 girls and 7 boys, who were treated either conservatively, by ACL reconstruction, by primary repair or by delayed ACL reconstruction after skeletal maturity had been reached. Clinical outcomes were measured using the International Knee Documentation Committee Scoring System (IKDC) and the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scoring System (KOOS). The radiological evaluation was performed using Jaeger and Wirth's criteria, and instrumented laxity testing was carried out with a Rolimeter. Five of the eight patients treated conservatively showed poor function of the knee, and this resulted in instability. Concerning the patients treated by primary repair, delayed ACL reconstruction or arthroscopic debridement, we also found none of the results to be satisfactory (seven of eight patients). The patients that were treated by a reconstruction had the best results. This was confirmed by clinical examination (Lachmann grade 1), by the IKDC (grade B) and by the KOOS with the best quality of life and no giving-way attacks. The level of evidence was therapeutic level III.

Résumé

Les ruptures du ligament croisé antérieur chez des jeunes patients qui ne sont pas encore à maturité osseuse deviennent de plus en plus nombreuses. Le but de cette étude est de décrire l’avenir fonctionnel et d’évaluer le meilleur traitement de ces ruptures du croisé antérieur chez des sujets au squelette immature. Vingt patients consécutifs en cours de croissance ayant présenté de façon évidente sur le plan clinique une rupture du ligament croisé antérieur ont été suivis sur une moyenne de 5,4 ans. L’âge moyen au moment du traumatisme était de 13,9 ans. Le groupe étudié consiste en 13 filles et 7 garçons qui ont tous été traités par reconstruction du ligament croisé antérieur de façon immédiate ou, par reconstruction secondaire après fermeture du cartilage de croissance. L’avenir clinique des patients a été étudié selon le score de l’IKDC et du KOOS. L’étude radiologique a utilisée les critères de Jaeger et de Wirth et la laxité a été mesurée avec un Rolimeter. Les patients ont été traités soit par réparation immédiate du ligament croisé antérieur soit par réparation secondaire. Cinq patients (62.5%) traités de façon orthopédique ont montré un résultat clinique médiocre avec une instabilité résiduelle. Les patients traités par réparation primaire ou secondaire du ligament croisé antérieur avec reconstruction ou nettoyage sous arthroscopie non, également pas eu de résultats satisfaisants pour sept d’entre-eux (87.5%). Les patients qui ont été traités par reconstruction ont eu de meilleurs résultats. Ceci a été confirmé cliniquement (Lachmann grade 1), score IKDC (grade B) et le score KOOS avec la meilleure qualité de vie. Niveau d’évidence thérapeutique : niveau III.

Introduction

Over the past 20 years, tears of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) have become more prevalent in the skeletally immature patient [8]. Thus, the documentation of ACL injuries in skeletally immature patients has significantly increased during the past decade [1–5, 7, 8, 10–12, 16, 19, 21, 23, 24]. Non-reconstructive treatment often leads to poor results, especially concerning sports activity and further meniscal and chondral injuries [20, 21]. Many surgical treatment options have been introduced, including primary repair and reconstruction, using both extra-articular as well as intraarticular procedures. Reports on primary repair and extraarticular reconstruction procedures have shown only little success at providing long-term knee stability [6, 17, 18]. On the other hand, intraarticular anatomical reconstruction of the ACL may lead to physeal injury and lower extremity deformities [14]. Others suggest that surgical correction with the use of techniques similar to those used in adult reconstruction produces satisfactory mechanical results without physeal damage, varus or valgus angulation or leg-length discrepancy [8, 12]. It is generally accepted that patients who are approaching skeletal maturity and have little growth potential can be treated as adults. The true controversy exists concerning the skeletally immature patient with a wide-open physis and significant growth potential. An option might be non-operative treatment until the patient is almost skeletally mature before performing the ACL reconstruction.

As our own treatment strategies have also varied during the past decade, we initiated a follow-up evaluation of our young patients with ACL ruptures. It was the aim of this study to describe the functional outcome of total ACL tears in skeletally immature patients comparing different treatment options.

Methods

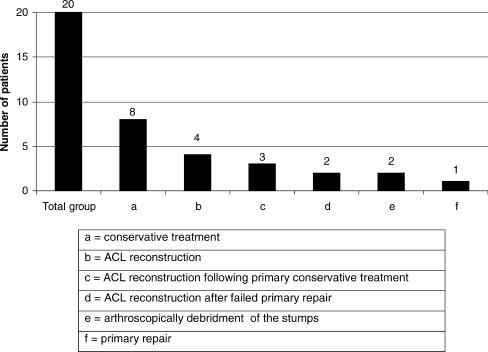

Between January 1994 and April 2004, we identified 63 patients (36 girls and 27 boys) younger than 16 years of age with a clinically evident ACL rupture. In this period, we treated a total of 3,078 ACL ruptures at our department. Of the 63 patients, 43 were lost to follow-up. The 20 patients included in the study were divided into six categories, according to their treatment: (a) conservative treatment (including physical therapy and bracing), 8 cases; (b) ACL reconstruction using a patellar tendon autograft when they had a wide-open physis, 4 cases; (c) ACL reconstruction after skeletal maturity, including primary conservative treatment, 3 cases; (d) ACL reconstruction after a failed primary repair, 2 cases; (e) arthroscopic debridement of the ACL stumps, 2 cases; (f) primary repair, 1 case (Table 1). Grafts were placed using a standard endoscopic ACL reconstruction technique, where tunnels were made through the proximal tibia and distal femoral physis and fixed with interference screws. The average age at the initial injury was 13.9 years old (range 9 to 15). The cause of initial injury in all cases was related to sports, mainly contact sports.

Table 1.

ACL treatment group, 20 cases

At the time of follow-up, all patients underwent a clinical examination, an X-ray and instrumented laxity testing using a Rolimeter. The physical examination included range of motion and testing of knee instability with a manual Lachmann test [13]. Radiologically, an anterior posterior, a lateral and a patellar skyline view were classified according to Jaeger and Wirth [15]. The Rolimeter was placed on the patient’s leg, which was fixed in 30° of flexion, and a modified Lachmann test was performed [9]. The anterior displacement could be then read directly from the 2-mm calibrations on the shaft of the stylus [9]. Furthermore, KOOS scoring software was downloaded in the German version from http://www.koos.nu. and completed by the patients [22].

Results

The mean follow-up from the time of the initial injury was 5.4 years (range, 6 to 125 months).

The overall IKDC score for the patients treated by reconstruction was grade B in all four knees. Concerning the three knees treated by secondary ACL reconstruction after conservative treatment, we found one patient scored grade A, another patient grade B and the third grade C. One of two patients who had an arthroscopic debridement of the ACL stumps scored grade C, and the other grade D. The patient who had a primary repair scored grade D. ACL reconstruction after failed primary repair led to a grade B in one patient and to a grade D in the other. Among the eight patients of the conservatively treated group, one scored grade B, two grade C and five grade D.

All of the four patients with ACL reconstruction had a grade 1 Lachman with a firm endpoint. In the conservatively treated group, two patients had grade 2 Lachmann and six patients had grade 3 Lachman, whereas only three patients had a firm endpoint. Among the three patients treated with delayed ACL reconstruction after conservative treatement, two had a grade 2 and one had a grade 3 Lachman, all without a firm endpoint. Of the two patients with delayed ACL reconstruction after failed primary repair, one patient had a grade 1 Lachmann and one a grade 3 Lachmann without a firm endpoint. The one patient who only was treated by primary repair showed a grade 3 Lachmann with a soft endpoint. Among the two patients treated by debridement of the stumps of the ligament, one had a grade two and one a grade 3 Lachmann sign, both with a soft endpoint.

Instrumented laxity testing revealed a mean anterior displacement for the ACL reconstruction of 4.8 mm (range, 4–7 mm) and 7.8 mm (range, 2–10 mm) for the knees treated conservatively. Concerning the three knees treated with delayed ACL reconstruction, the mean anterior displacement was 4.3 mm (range, 2–7 mm) and 8.5 mm (range, 7–10 mm) for the knees treated with arthroscopic debridement of the stumps. The anterior displacement for the two knees treated with delayed ACL reconstruction after failed primary repair was 7 mm (4–10 mm) and for the one knee treated by primary repair, 10 mm.

Radiological signs of degenerative changes were seen in 17 (85%) patients: grade 1 in 13 (65%) and grade 2 in 4 (20%) patients, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Radiological signs, according to Jaeger and Wirth

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | ||

| Total (17 patients) | 13 | 4 |

| Conservative treatment | 5 | 1 |

| Primary ACL reconstruction | 3 | 1 |

| ACL reconstruction following primary conservative treatment | 2 | |

| ACL reconstruction after failed primary repair | 2 | |

| Artroscopic debridment of the stumps | 2 | |

| Primary repair | 1 | |

In accordance with the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scoring System (KOOS), knee function was fair in nearly all 20 cases as shown in Table 3. None of the patients suffered from massive pain symptoms. The most common symptoms were swelling, and sometimes the feel of grinding or clicking was present. Some of the patients also mentioned that their knee caught or got hung up when moving. According to sports in the group of ACL reconstruction, all four patients returned to their preinjury sports level, but they had problems with kneeling on the affected side. In the conservatively treated group, only four (half) returned to their preinjury sports level. In the patients treated with delayed ACL reconstruction, only one returned to the preinjury level. In the two treated by ACL reconstruction after failed primary repair, only one returned to the preinjury level. The one patient who was managed by primary repair did not return to the preinjury level neither did the two patients treated with arthroscopic debridement of the stumps.

Table 3.

Koos Scoring System

| Conservative treatment | ACL reconstruction | ACL reconstruction following conservative treatment | ACL reconstruction after failed primary repair | Arthroscopically debridement of the stumps | Primary repair | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 93 | 91 | 94 | 86 | 97 | 86 |

| Symptoms | 88 | 81 | 95 | 87 | 89 | 75 |

| Quality of life | 72 | 84 | 65 | 69 | 66 | 82 |

| Sports and recreation function | 86 | 74 | 82 | 57 | 67 | 80 |

| ADL function | 99 | 91 | 100 | 69 | 97 | 100 |

None of the patients had problems achieving daily living activities. Overall, the quality of life was best in patients treated by ACL reconstruction. Half of the patients treated conservatively mentioned giving-way episodes as did two thirds of the group treated with ACL reconstruction after conservative therapy. Everyone in the group treated with arthroscopic debridement mentioned giving-way episodes, as did the one patient by primary repair. The patients treated by reconstruction did not complain about instability.

Discussion

Total tears of the ACL in the skeletally immature patient are being recognised with increasing frequency. Nevertheless, the management of an ACL rupture in the skeletally immature patient continues to be a highly controversial topic. Our study population confirms the variability in treating skeletally immature patients with a ruptured ACL.

Mizuta et al. reported on 18 skeletally immature patients who were treated conservatively [20]. All 18 patients had symptoms of instability and complained of pain, and only 1 returned to the previous level of athletic activity. They demonstrated poor and unacceptable results for conservative treatment in this age group. McCarroll et al. [17] treated 16 patients conservatively. Only 7 patients returned to sports, and all 16 patients experienced giving way, effusions and pain. Aichroth et al. [2] reported on 23 patients who were treated conservatively and had results of severe instability and poor functional outcome. This has been our experience, too: Half (four) of the patients treated conservatively reduced their sports activity, and when examined on follow-up, seven patients showed a positive Lachman without a firm endpoint.

Surgical treatment procedures for total tears of the ACL include primary repair, extra-articular reconstruction as well as intra-articular reconstruction. Fuchs et al. reported on ten skeletally immature athletes with transphyseal intra-articular ACL reconstruction [8]. Nine patients returned to their preinjury level of athletics. No patients complained about instability, and there was no limb-length discrepancy or early physeal arrest evident.

Pressman et al. reported on 16 children treated non-operatively by primary repair or by intra-articular ACL reconstruction [21]. ACL reconstruction resulted in the best outcome. Engelbretsen et al. reported on eight patients between 13 and 16 years of age treated by primary repair and found that all patients decreased their level of sports activity, and five had a positive Lachman sign [6]. Similar results were seen in the present series. The one patient treated with primary repair only had an IKDC grade D, a Lachman grade 3 with a soft endpoint, and was not able to return to his pre-injury level. The other two patients had a primary repair first followed by ACL reconstruction because of failure. One of them had an IKDC grade B, and the other grade D; both showed a positive Lachman sign grade 2, one with a soft endpoint. Janarv et al. reported on 28 patients [12]. Twenty-three were sent to 3-month rehabilitation, and five patients had a reconstruction avoiding the growth plate. The patients not operated on had a lower activity level at follow-up. Millett et al. reported on 39 patients with an average age of 13.6 years (range: 10 to 14 years) who underwent surgical treatment of the ACL [19]. He analised the relationship between meniscal injury and the time from injury to surgery and found a significant association. Meniscal tears were more common in the group where surgery was performed 6 weeks after the injury. The data show that a delay in surgical treatment is associated with a higher frequency of meniscal tears. Finally, Attmanspacher et al. reported on 45 children with intraarticular reconstruction [4]. None of the patients suffered from an ill-functioning growth plate, and all reflected a good to very good result with an IKDC of grade A or B. These findings support our results with excellent results also in the patients treated with reconstruction.

Komann et al. reported on a 14-year-old boy who received a transphyseal intra-articular reconstruction of the ACL and had premature closure of the distal femur physis that resulted in a valgus deformity of the lower extremity [14]. They suggest a delayed reconstruction of a ruptured anterior cruciate ligament until the patient reaches skeletal maturity.

Recently, Anderson published a series of 12 patients, children and adolescents with a mean age of 13.3 years (range, 11.1–15.9 years) with a rupture of the ACL [3]. Determining the patient’s biological age, the criteria for staging, described by Tanner and Whitehouse, were performed [25]. He performed a hamstring autograft ACL reconstruction in a transepiphyseal technique by avoiding the physis. The results were good, and the author recommended the use of this technique for aggressive treatment of patients who are in Tanner stage I or II of development. However, an increase in participation in high-demand ACL sports at an earlier age is expected and needs further investigation to understand differences in stability, following reconstruction or non-operative treatment in skeletally immature patients with an ACL rupture and to determine indications.

Conclusion

All of our patients treated with intraarticular ACL reconstruction returned to their preinjury level; none of the patients had evidence of early physeal arrest, varus or valgus angulation or limb length discrepancy. Delayed ACL reconstruction with a progressive program including bracing, cryotherapy and a rehabilitation effort to restore muscle balance to the lower extremity might be an option for patients who have contraindications to or refuse surgery. Despite our small series of patients, we suggest that skeletally immature patients with symptomatic ACL tears may benefit from early reconstruction.

References

- 1.Adirim T, Cheng T (2003) Overview of injuries in the young athlete. Sports Med 33(1):75–81 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Aichroth PM, Patel DV, Zorilla P (2002) The natural history and treatment of rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament in children and adolescents. JBJS [BR] 84:38–41 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Anderson AF (2003) Transepiphyseal replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament in skeletally immature patients. J Bone Joint Surg 85-A;(7):1255 – 1263 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Attmanspacher W, Dittrich V, Stedtfeld HW (2003) Behandlungsergbnisse nach operativer Versorgung kindlicher Kreuzbandrupturen. Unfallchirurg 106:136–143 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dorizas JA, Stanitski CL (2003) Anterior cruciate ligament injury in the skeletally immature. Orthop Clin N Am 34:355–363 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Engebretsen L, Svenningsen S, Benum P (1988) Poor results of anterior cruciate ligament repair in adolescence. Acta Ortop Scand 59:684–686 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Fehnel DJ, Johnson R (2000) Anterior cruciate injuries in the skeletally immature Athlete. Sports Med 1:51–63 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Fuchs R, Wheatley W, Uribe JW, Hechtmann KS, Zyijac JE, Schurhoff MR (2002) Intra-articular cruciate ligament reconstruction using patellar tendon allograft in the skeletally immature patient. Arthroscopy 18:824–828 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ganko A, Engebretsen, Ozer H (2000) The Rolimeter: a new arthrometer compared with the KT-1000. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 8:36–39 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.George A, Paletta JR (2003) Special considerations Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the skeletally immature. Orthop Clin N Am 34:65–77 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Guzzanti V., Falciglia F, Stanitski CL (2003) Physeal-sparing intrarticular anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in preadolescents. Am J Orthop Sports Med 31:949–953 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Janarv PM, Nyström A, Werner S, Hirsch G (1996) Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in skeletally immature patients. J Pediatr Orthop 16:673–677 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Johnson DS, Ryan WG, Smith RB (2003) Does the Lachmann testing method affect the reliability of the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) Form? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 12:225–228 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Koman J, Sanders J (1999) Valgus deformity after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament in a skeletally immature patient. J Bone Joint Surg 81-A(5):711–715 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Krämer KL, Maichl FP (1993) Scores, Bewertungsschemata und Klassifikationen in Orthopädie und Traumatologie. Thieme 400

- 16.Lo IKY, Kirkley A, Fowler PJ, Miniaci A (1997) The outcome of operativley treated anterior cruciate ligament disruptions in the skeletally immature child. Arthroscopy 13:627–634 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.McCarroll JR, Rettig AC, Shelbourne KD (1988) Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the young adult with open physes. Am J Sports Med 16:44–47 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.McCarroll JR, Shelbourne KD, Porter DA, et al (1994) Patellar tendon graft reconstruction for midsubstance anterior cruciate ligament rupture in junior high school athletes. Am J Sports Med 22:478–484 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Millet P, Willis A, Warren R (2002) Associated injuries in pediatric and adolescent anterior cruciate ligament tears: Does a delay in treatment increase the risk of meniscal tear? Arthroscopy 18(9):955–959 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Mizuta H, Kubota K, Shiraishi M, Otsuka Y, Nagamoto N, Takagi K (1995) The conservative treatment of complete tears of the anterior cruciate ligament in skeletally immature patients. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 77:890–894 [PubMed]

- 21.Pressman AE, Letts RM, Jarvis JG (1997) Anterior cruciate ligament tears in children: An analysis of operative versus nonoperative treatment. J Pediatr Orthop 17:505–511 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Roos EM, Lohmander LS (2003) The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Simonian PT, Metcalf MH, Larson RV (1999) Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the skeletal immature patient. Am J Orthop 28:624–628 [PubMed]

- 24.Stanitski CL (1995) Anterior cruciate ligament injury in the skeletal immature patient: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 3:146–158 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH (1976) Clinical longitudinal standards for height, weight height velocity, weight velocity and stages of puberty.Arch Dis Child 151:170–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]