Abstract

Astroglia are known to potentiate individual synapses, but their contribution to networks is unclear. Here we examined the effect of adding either astroglia or media conditioned by astroglia on entire networks of rat hippocampal neurons cultured on microelectrode arrays. Added astroglia increased spontaneous spike rates nearly two-fold and glutamate-stimulated spiking by six-fold, with desensitization eliminated for bath addition of 25 μM glutamate. Astrocyte-conditioned medium partly mimicked the effects of added astroglia. Bursting behavior was largely unaffected by added astroglia except with added glutamate. Addition of the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline also increased spike rates but with more subtle differences between networks without or with added astroglia. This indicates that networks without added astroglia were inhibited greatly. In all conditions, the log–log distribution of spike rates fit well to linear distributions over three orders of magnitude. Networks with added astroglia shifted consistently toward higher spike rates. Immunostaining for GFAP revealed a linear increase with added astroglia, which also increased neuronal survival. The increased spike rates with added astroglia correlated with a 1.7-fold increase in immunoreactive synaptophysin puncta, and increases of six-fold for GABAAβ, two-fold for NMDA-R1 and two-fold for Glu-R1 puncta, with receptor clustering that indicated synaptic scaling. Together, these results indicate that added astroglia increase the density of synapses and receptors, and facilitate higher spike rates for many elements in the network. These effects are reproduced by glia-conditioned media, with the exception of glutamate-mediated transmission.

Keywords: multielectrode array, synaptogenesis, neuron–glia cell culture, serum-free culture, synaptic scaling

INTRODUCTION

Astroglia promote the synaptic efficiency of individual neurons. Carefully controlled studies of retinal ganglion cells cultured in Neurobasal/B27 serum-free medium monitored by patch-clamp produced more and higher amplitude postsynaptic currents after 20 days of culture when astroglia were added to the cultures at day 5 (Pfrieger and Barres, 1997). When the effects of added astroglia were mimicked by glia-conditioned medium, the effects were attributed to trophic factors released by astroglia. The increase with added astroglia was accompanied by a larger presynaptic quantal content, a higher density of glutamate receptors (Glu-R2/3) and more synaptophysin puncta per cell despite no changes observed in the morphology of individual synapses by electron microscopy (Ullian et al., 2001). The impact of these increases in individual synaptic events on larger networks and resultant action potentials has not been determined. A naive hypothesis is that integration of greater individual synaptic efficacy might lead to hyperexcitability. However, some mechanisms appear to modulate overall activity by balancing excitatory and inhibitory inputs to prevent epileptic bursting (Chih et al., 2005; Koester and Johnston, 2005). Turigiano's group has found ranges for balancing of inward and outward currents that prevent bursting during changes in input excitation (Turigiano et al., 1995). They also have evidence for control of this synaptic scaling by brain-derived growth factor (BDNF) (Rutherford et al., 1997), postsynaptic polarization (Leslie et al., 2001) and Calcium/Calmodula-dependent protein Kinase II (CaMKII) (Pratt et al., 2003). Here, we probe excitatory synapses with glutamate and inhibitory GABAA receptors with bicuculline (Barbin et al., 1993), and determine receptor densities to further characterize the effect of medium conditioned by either astroglia or glia on network dynamics.

The network properties of neurons are explored using dissociated culture, brain slice and in vivo work, each of which has its own advantages and disadvantages for ease of experimentation and extrapolation to whole animal physiology. Brain slices, either acute or in culture, offer a more natural network structure but are less amenable to manipulation of cell type and, because of current spread within the slice, customarily yield field potentials from synchronized firing detected with multi-electrode arrays (MEAs) rather than action potential data from individual neurons (Novak and Wheeler, 1989; Steidl et al., 2006). In vivo networks provide a standard for comparison but are less easily manipulated and observed. Here, we exploit the ability to manipulate the cell type composition of more simple networks to gain greater insight into the role of one of the fundamental constituents of the network: the astroglial cell or astrocyte.

To determine network properties of neurons, dissociated cells can be cultured on planar microelectrode arrays (Thomas et al., 1972; Gross, 1979; Pine, 1980). Correlated spontaneous and either electrically or pharmacologically stimulated activity can be easily recorded from 60 electrodes simultaneously (Keefer et al., 2001). However, growing neurons in medium that contains serum causes the proliferation of astroglia, which can undermine the close proximity of neurons to the microelectrodes (Wyart et al., 2002; Wheeler and Brewer, personal observation). One solution to this is to culture neurons in serum-free medium, which inhibits astroglial growth (Brewer et al., 1993). In the course of this work, we observed lower levels of neuronal activity than others report. Because astroglia mature several weeks after neurons in the rat brain (Abney et al., 1981) and are desirable for maximum activity (Banker, 1980; Li et al., 1998; Liu et al., 1998), a possible solution to the dilemma of using serum-free medium with a few glia compared with serum-containing medium with many glia is to add extra astroglia to established neuronal cultures. A particular advantage of the dissociated cultures exploited here is that the cell-type composition of the culture can be manipulated easily. The network consequences of adding either astroglia or glia-conditioned medium for higher network activity are presented here.

Most neuronal cultures begin with either embryonic neurons or early postnatal slices in which new neurons are initially insensitive to excitatory glutamate but depolarize in response to GABA acting as an excitatory transmitter (Barker et al., 2000). As the neurons mature and membrane pumps change the trans-membrane Cl− potential from negative to positive, GABA becomes an inhibitory transmitter (Rivera et al., 1999). By studying the cultures pharmacologically with the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline and the excitatory transmitter glutamate, we determined the relative effect of added astroglia on the maturation process.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study was to determine the effect on network activity of either astroglia or glia-conditioned medium added to hippocampal neurons in serum-free culture. Using multielectrode arrays, we recorded from up to 60 electrodes simultaneously to test the hypothesis that added astroglia increase spike rates and synaptogenesis without producing uncontrollable bursting. Additionally, we demonstrate appropriate methods of analysis of non-Gaussian distributions of activity data. We also probed the network pharmacologically and immunochemically to determine excitatory and inhibitory receptor activity.

METHODS

Culture

E18 hippocampal neurons were plated at 500 cells mm−2 in 1 ml Neurobasal/B27/0.5 mM glutamine medium (Invitrogen) on MEAs before addition of astroglia (Brewer et al., 1993). MEAs and glass coverslips were precoated with 100 μg ml−1 poly-D-lysine for 24 hours. Astroglia were cultured from E18 rat hippocampi at 200–300 cells mm−2 in Neurobasal medium, 2 mM glutamine supplemented with 10% horse serum for two weeks with 50% medium changes every 3–4 days. Three days before harvest, we made a 50% medium volume transition to Neurobasal/B27/0.5 mM glutamine. Astroglia were harvested with 0.25% trypsin for 2 min at 37°C, collected by centrifugation, resuspended in Neurobasal/B27/0.5 mM glutamine, and added to 8-day-old cultures of neurons at 500 cells mm−2 unless otherwise stated. For glia-conditioned medium experiments, two-week-old glia cultures received a full NB/B27 medium change 1 day before collection of the glia-conditioned medium. Glia conditioned medium was first mixed with 1.5 volumes of fresh Neurobasal/B27 medium. Beginning at 8 days of neuron culture, 50% of the culture medium was diluted with glia-conditioned medium followed by similar changes every fourth day until the cultures were at least 21 days in vitro. All cultures were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, 9% O2, balance N2 at 37°C (Forma).

MEAs

MEAs were obtained from Multichannel Systems (MCS) with 60 TiN3 electrodes of 20 μm diameter on 200 μm spacing. We also used an MCS amplifier, temperature controller set to 37°C and software to collect and analyze data. A custom metal cover was used to provide an electrical shield and an enclosure for a continuous flow of hydrated, sterile-filtered 5% CO2, 9% O2, balance N2 (AGA). After a settling time of 1 min, data were collected for 30–60 sec at 25 kHz with high-pass filtering at 10 kHz. For less active arrays, waiting up to 20 min did not increase activity. The spike-sorter function of MCRack (MCS) was used to determine spike rates with a threshold crossing at five standard deviations above background. The analyzer function was used to count spikes in 30 sec bins. For log transformations of spike rates, inactive electrodes were recoded from 0 (whose logarithm is meaningless) to a minimum of 0.016 Hz. For burst analyses, electrode activity was reviewed in pCLAMP (Axon Instruments) to select records with one or more busts. We used Clampfit's Burst Analysis tool to acquire statistics for bursts with ≥3 spikes and an interspike interval of <100 ms.

Drugs

Pharmacological manipulations were conducted by removing 200 μl from the 400 μl medium above the cells, followed by addition of 200 μl 2 × concentrated drug in medium to equal the following final concentrations: bicuculline methiodide, 10 μM; glutamate, 25 μM; tetrodotoxin (TTX), 1 μM (all Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals). Washout was conducted by removal of most of the medium followed by replacement with 37°C fresh medium without drugs. Recovery of activity after TTX was taken as evidence that washout was sufficient to remove drug additions.

Immunocytology and fluorescence microscopy

For immunocytology, all cultures were rinsed twice in warm PBS. Cells for synaptophysin- and microtubule associated protein (MAP2)- staining were fixed for 30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.03% glutaraldehyde in PBS. Cells for GFAP- and MAP2-staining were fixed for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells for NR1/Glu-R1- and NR1/ GABAAβ-staining were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 10 min. Cells were rinsed in PBS twice after fixing. Non-specific sites were blocked and cells were permeabilized for 5 min in 5% normal goat serum, 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS. All primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 5% NGS, 0.05% TX-100 in PBS. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 24 hours at 4°C as follows: rabbit-anti-MAP2 (1:100, Chemicon); mouse-anti-synaptophysin (1:1000, Sigma S5768); mouse-anti-GFAP (1:1200, Sigma); rabbit-anti-NMDA-R1 (1:100, Sigma); mouse-anti- GABAAβ (1:50, Chemicon); rabbit-anti-Glu-R1 (1:3000, Upstate Biotechnology); and mouse-anti-NMDA-R1 (1:50, Chemicon). After rinsing four times with PBS, cells were incubated for 1 hour at 22°C with either Alexa-fluor 568-conjugated affiniPure goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy + light chain, 1:2000, Molecular Probes) together with conjugated Alexa-fluor 488 affiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (heavy + light chain, 1:50, Molecular Probes) or Alexa-fluor 568 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (heavy + light chain, 1:100 Molecular Probes) together with Alexa-fluor 488 conjugated goat anti-mouse (heavy + light chain, 1:300, Molecular Probes). After rinsing four times in PBS, the nuclei of cells were stained for 2 min at 22°C with bisbenzamide (Sigma) diluted in PBS to a final concentration of 1 μg ml−1. After two final rinses, coverslips were mounted with Aquamount and imaged through a Nikon 20 × /0.4 or 100 × /1.4 objective, collected with a cooled CCD Retiga Exi camera (Q Imaging). Cells stained for GABAAβ, NR-1 and Glu-R1 were imaged through an Olympus 60 × /1.42 objective.

Image analysis

Image-Pro 4.5.1 was used for image analysis, with specific techniques for either digital analysis or display. For puncta stained with synaptophysin, a two-pass large spectral filter was used along with two histogram-based segmentation thresholds. A high threshold was used to detect bright objects around the soma and a low threshold was used to detect dimmer objects in the processes. Counts from these two settings were combined for each field sampled. For GABAAβ, NR-1 and Glu-R1 puncta analysis, digital segmentation also required separation into bright and dim classes because the large range of intensity of the fluorescent puncta. Threshold settings were consistent for all slips evaluated. To count puncta, an area limit of 0.008–0.5 μm2 was used (field size for the100 × objective = 0.0056 mm2; minimum area of 0.008 μm2 = 3 pixels). Puncta area limits for GABAAβ and NR1 were 0.015–2 μm2; and for Glu-R1 0.02–2 μm2 (field size for the 60 × objective = 0.016 mm2; minimum area of 0.015 μm2 = 4 pixels). Mean density was also measured for GABAAβ, NR-1, and Glu-R1 puncta. Measurement filters for GABAAβ, NR-1 and Glu-R1 counts included zero holes to avoid circumferential distributions and roundness 0.5–3 to avoid long strings of stained objects on the selected measurements menu that served to objectively focus counts of more round isolated puncta. A special background dark filter and consistent histogram-based segmentation threshold was used on all pictures of bisbenzamide images. Bisbenzamide-stained nuclei were counted manually. For display, a mask was applied from the threshold and saved as a new image. To enhance MAP2 staining, consistent background subtraction was applied to all images. Nuclei with surrounding MAP2 staining were counted manually. For MAP2 areas and densities, a consistent histogram-based threshold was applied with an area minimum of 5000 μm2. Colored pictures from all three stains were combined with the merging function in the color channel process tab.

RESULTS

Effects of added astroglia on spike rate

In an attempt to increase the low spike rates in neuronal cultures grown in serum-free Neurobasal/B27 medium, and the overgrowth of astroglia that occurs in serum-containing medium, we added to 1-week-old neuronal cultures astroglia that had been cultured separately in serum-containing medium as a feeder stock. Direct addition of these harvested astroglia resulted in death of the neuronal layer and the added astroglia (data not shown). If we conditioned the astroglial culture by change of the 50% medium to serum-free Neurobasal/B27, as described in Methods, we were able to add varying proportions of astroglia to the neurons with good survival of both in serum-free medium.

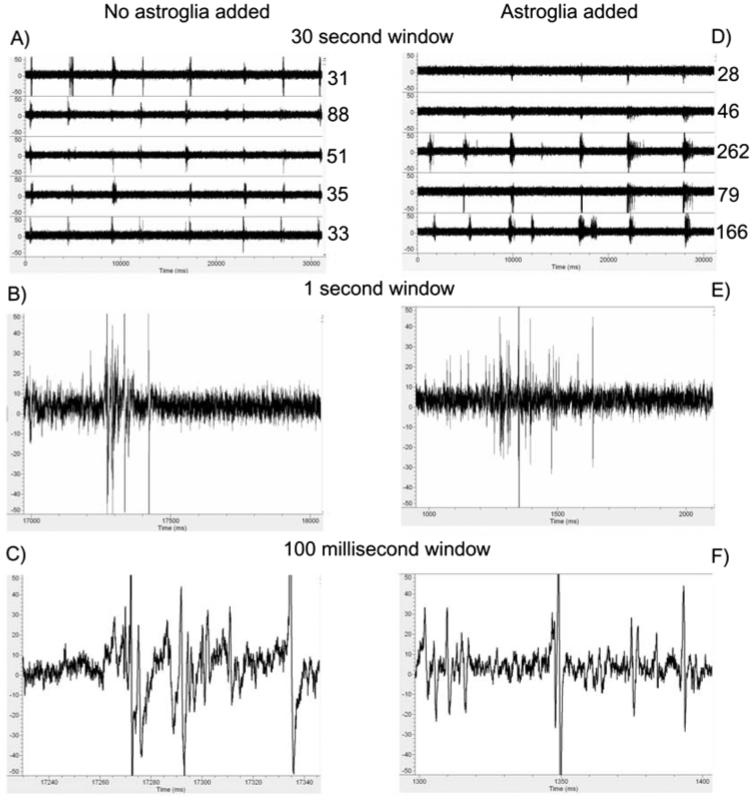

From arrays with 60 electrodes that were plated at 500 neurons mm−2, we recorded spontaneous activity in the neuronal network after 3 weeks of culture. Data in Fig. 1 compares initial activity between cultures with no added astroglia and cultures with an additional, equal number of astroglia per mm. For the 30-sec traces shown for five electrodes (Fig. 1A,D), spike rates were higher in the culture with added astroglia. Spiking activity was more frequent with added astroglia and more bursts were apparent. To rule out stray noise as spiking activity, a closer analysis of the wave forms are displayed in 1-sec windows (Fig. 1B,E) and 100-msec windows (Fig. 1C,F). The wave forms were similar between groups with mostly bipolar potentials of 2–3 msec widths.

Fig. 1. More action potentials are detected on multielectrode arrays to which astroglia were added.

Action potential activity of cultures (22 days in vitro) without added astroglia (A,B,C) and with added astroglia (D,E,F). Traces from five electrodes for 30 sec of spike activity with added astroglia (D) have more activity and longer bursts than without added astroglia (A). Numbers indicate spike counts at +5 S.D. above noise. Spike waveforms and shape are similar between groups at 1 sec (B,E) and 100 msec (C,F).

Separate analysis of signal deviation from the mean when no action potentials were present (noise) was conducted to determine if subthreshold events contributed to the recorded signals. This noise signal for four arrays (32 electrodes) decreased from 3.5±0.2 μV for cultures without added astroglia to 2.9±0.1 μV with added astroglia (P=0.02), measured as a mean and standard deviation. This decrease in noise with added astroglia indicates more uniformity in the noise for cultures with astroglia.

We analyzed the clustering of action potentials into closely spaced bursts of activity, as seen in Fig. 1. The duration of the bursts, spikes per burst and bursts per minute were all unaffected at baseline by addition of astroglia (Table 1). Addition of astroglia caused a 25% decrease in intra-burst interval (Fig. 1B versus 1E). 12–18% of activity on electrodes with bursts was as single spikes at 10–16 spikes minute−1, and not significantly affected by added astroglia. In contrast to the above analysis for electrodes with bursts, 33–40% of electrodes showed activity without bursts at 14–19 spikes minute−1.

Table 1.

Burst characteristics affected by addition of astrogliaa

| Initial |

After bicuculline |

After glutamate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n (electrodes) |

Without Astroglia (32) |

With Astroglia (47) |

Without Astroglia (47) |

With Astroglia (49) |

Without Astroglia (16) |

With Astroglia (73) |

| Duration of burst (msec) | 133 ± 9 | 118 ± 11 P ns |

180 ± 17 P2=0.02 |

270 ± 23 P3=0.002 P4<10−4 |

>200 P2<10−4 |

102 ± 4.7 P3<10−4 P4 ns |

| Intraburst interval (msec) | 20 ± 1.4 | 15 ± 1.0 P=0.01 |

12 ± 1.1 P2<10−4 |

17 ± 1.1 P3=0.0006 P4 ns |

>100 P2<10−4 |

28 ± 1.0 P3<10−4 P4<10−4 |

| Spikes/burst | 11 ± 1.0 | 11 ± 1.3 P ns |

24 ± 2.2 P2<10−4 |

30 ± 3.1 P3 ns P4<10−4 |

<3 P2<10−4 |

8.5 ± 0.24 P3<10−4 P4=0.03 |

| Bursts/min | 6.9 ± 0.9 | 6.6 ± 0.6 P ns |

10.0 ± 1.0 P2=0.03 |

8.8 ± 1.4 P3 ns P4 ns |

0 P2<10−4 |

11.7 ± 2.7 P3<10−4 P4 ns |

| Burst spikes/min | 75 ± 17 | 75 ± 19 P ns |

240 ± 44 P2=0.0008 |

265 ± 60 P3 ns P4=0.003 |

0 P2<10−4 |

75 ± 18 P3<10−4 P4 ns |

| Non-bursting spikes/min | 10.4 ± 1.0 | 16 ± 5.0 P ns |

22 ± 4.8 P2=0.02 |

15 ± 3.6 P3 ns P4 ns |

5.6 ± 1.7 P2=0.01 |

46 ± 11 P3=0.0004 P4=0.01 |

| Non-burst analysis (spikes/min b ) |

19 ± 5.4 n=16 |

14 ± 2.6 n=32 P ns |

18 ± 6.1 n=15 P ns |

31 ± 6.7 n=57 P3 ns P4=0.02 |

1.8 ± 0.31 n=16 P2=0.004 |

10.3 ± 4.1 n=47 P3=0.04 p4 ns |

| % Burst spikes/min | 88 | 82 | 92 | 95 | 0 | 62 |

|

% Burst spikes/min (using non-burst analysis spikes/min)b |

72 | 71 | 86 | 85 | 0 | 57 |

Data from three arrays, considering electrodes with bursting behavior only.

Complementary to the burst analysis, non-burst analysis (italics) includes all other electrodes with >1 spike, without bursting behavior.

P, probability between initial conditions with and without astroglia.

P2, probability between cells without astroglia, before and after bicuculline or glutamate.

P3, probability between cells after bicuculine or glutamate with and without astroglia.

P4, probability between cells with astroglia, before and after bicuculline or glutamate.

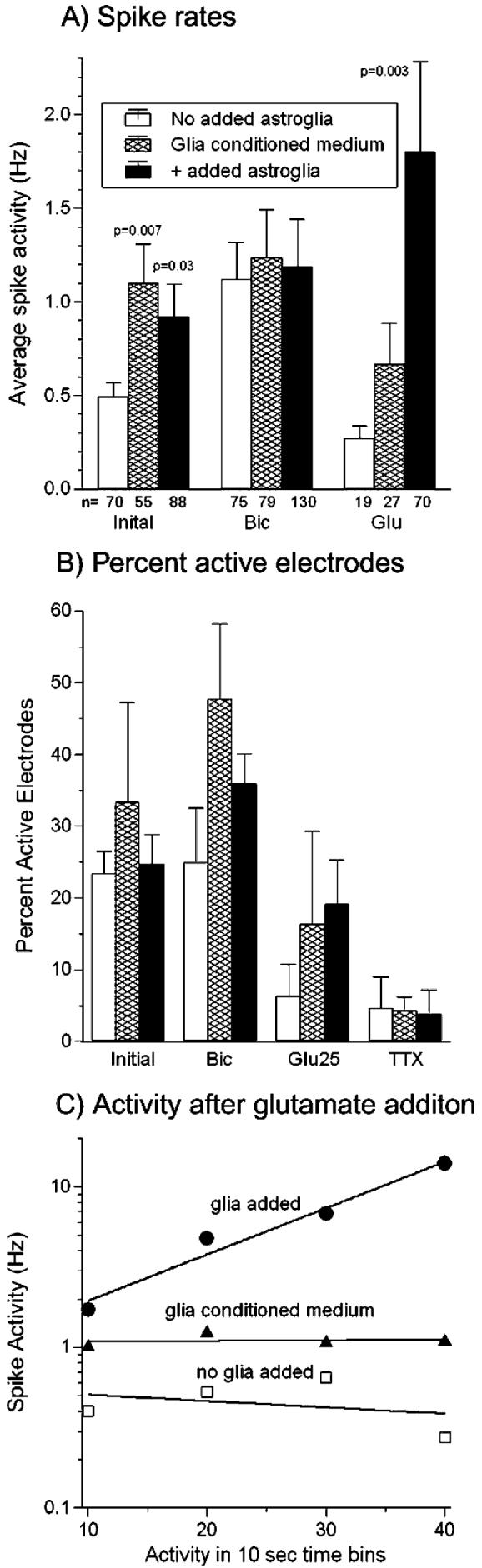

Fig. 2A shows a 1.9-fold increase in overall spontaneous spike activity for five arrays with added astroglia (0.92 Hz; 500 astroglia added mm−2), which was reproduced by astrocyte-conditioned medium, compared to five arrays without added astroglia (0.49 Hz). To probe the level of inhibitory connections in the network, we added 10 μM bicuculline, a GABAA receptor antagonist, to the cultures. As seen in Fig. 2A, spike rates increased by blocking inhibition through GABA receptors, and there was no difference between the networks cultured either without or with added astroglia and with astrocyte-conditioned medium (a more detailed analysis is presented later). In networks without added astroglia there was a larger (2.9-fold) increase in activity compared with a 1.5-fold increase in activity for networks with added astroglia. However, the apportioning of individual spikes into bursts was altered, with 50% increases in burst duration and intra-burst interval with added astroglia resulting in no net increase in spike rates in bursts (Table 1). As indicated by the number of active electrodes below each bar, bicuculline activated previously silent neurons over electrodes, especially with glia-conditioned medium or added astroglia. However, variability between arrays prevented a significant conclusion about the percentage of active electrodes for any treatment (Fig. 2B). At a power of 0.8 and effect size of 1.4, significance might be achieved if the number of arrays doubled from 5 to 10. The decrease in active electrodes after TTX indicates the Na+ channel-dependence of action potentials that were measured previously.

Fig. 2. Average spike rates increase with added astroglia and in response to glutamate with less desensitization.

(A) Initial spike rates show a 1.9-fold mean increase for arrays with added astroglia and 2.0-fold increase with glia-conditioned medium compared to arrays without added astroglia. Bicuculline addition raised spike rates and the number of active channels (n), however, there was no difference in rate between networks with and without added astroglia or with glia-conditioned medium. Glutamate addition to cultures with astroglia produced a 6.7-fold mean increase in activity over arrays without added astroglia (P=0.003) and a 2.6-fold increase over glia-conditioned medium. P values show significant differences from no glia added condition by t-test. (B) Active electrodes per 60 electrode array tends to increase with added astroglia or glia-conditioned medium (letter-toe) (n = 300 electrodes) compared to no added astroglia. (C) Spike activity immediately following the addition of glutamate in 10-sec bins shows increased activity 10–40 sec after addition of glutamate in a culture with added astroglia (●, slope = 0.029, n=28–51 electrodes). A decrease or lower activity is seen over the same time period in a culture without added astroglia (□, slope = −0.004, n=2–8 electrodes) and in a culture with glia-conditioned medium (▲, slope=0.0004, n=14–34 electrodes). In all evaluations, electrodes with either 0 or 1 spike were not included in the averages. Cultures were 22–29 days in vitro.

Excitatory connections were probed by the addition of 25 μM glutamate in the presence of the co-agonist glycine (400 μM) in the recording medium. Initial experiments in which glutamate was added before bicuculline showed low response rates. Therefore, subsequent experiments with glutamate were conducted after bicuculline and a washout period, which might also lower the concentration of endogenous, inhibitory GABA. In networks without added astroglia, activity desensitized (Fig. 2C) so that mean spike rates and the percentage of active electrodes were lower in the presence of glutamate than in the resting state (Fig. 2A,B). In cultures with added astroglia, glutamate stimulated neurons to spike at significantly higher rates than those without added astroglia (6.7-fold, Fig. 2A) and steadily increased network activity (Fig. 2C). Addition of astrocyte-conditioned medium also increased glutamate-stimulated spike rates, but to a lesser extent than added astroglia. Table 1 shows the elimination of bursting behavior by addition of glutamate without added astroglia. However, in the presence of added astroglia, bursting and non-bursting activity increased greatly. Glia-conditioned medium failed to increase spike rates stimulated by either glutamate or added astroglia (Fig. 2A,C).

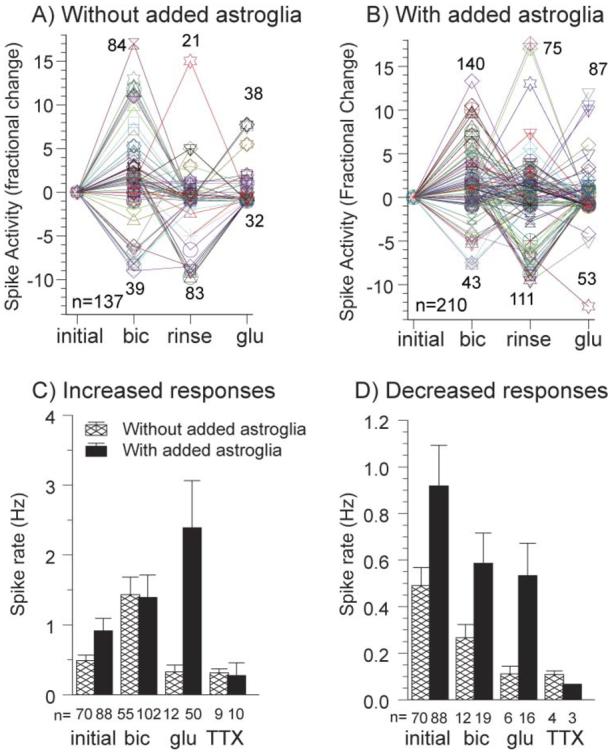

Two aspects of the above data indicate that these analyses are simplistic. First, the response to the pharmacologic agents was not uniform, producing increases in spike rates on some electrodes and decreases in spike rates on others, as is expected of a network with both mature and immature neurons with both inhibitory and excitatory inputs. Second, the distribution of frequencies was non-Gaussian, with a long tail at higher frequencies, which implies that simple statistics are inappropriate.

To address the first problem of some neurons stimulated and others inhibited by the same drug, activity was evaluated for each individual electrode as either a positive or negative fractional change from the preceding condition (Fig. 3A,B). Bicuculline increased activity on 82–84% of active electrodes and decreased responses on 16–18% of active electrodes (either with or without added astroglia) (Fig. 3C,D and Table 2). For the increases without added astroglia, the 2.9-fold increase in rate for bicuculline relative to the initial rate indicates that there are more inhibitory neurons in these cultures than in cultures with added astroglia (1.5-fold increase) (Fig. 3C, Table 2). After glutamate without added astroglia, Fig. 3C shows a rate of 0.3 Hz. This is an increase only because these electrodes reported from a subclass of neurons with very low initial rates. However, relative to the entire population of initially responding electrodes the change is 0.7-fold (i.e. lower) (Table 2). For networks without added astroglia, this complements the bicuculline data and indicates a low proportion of excitatory neurons. By contrast, for networks with added astroglia in which glutamate increased activity (Fig. 3C), the increase was 2.6-fold, which indicates that these networks might incorporate more excitatory neurons. Fig. 3D and Table 2 also show significant differences in the decreased response to either bicuculline or glutamate between networks without and with added astroglia in 24–29% of electrodes reporting. This small fraction of decreased responses to bicuculline presumably reflects a small fraction of excitatory GABAergic synapses (Rivera et al., 1999). Finally, tetrodotoxin decreased activity in all cases, but the fold decrease was greater for the astroglia-added cultures (Table 2).

Fig. 3. Separation of increased from decreased spike rates on each electrode increases effect of added astroglia with glutamate to 7-fold.

Fold increase or decrease in spike rate for individual electrodes after initial activity in cultures without added astroglia (A) and cultures with added astroglia (B). Changes are relative to the preceding condition with numbers of responding electrodes indicated near the peaks and numbers of electrodes active under any condition in the lower left. (C,D) Mean rates for cultures with added astroglia and without added astroglia for increased responses (C) and decreased responses (D) relative to initial activity. For increased responses, after glutamate addition, cultures with astroglia added have >7-fold higher activity than cultures without added astroglia (C) responses (P=0.003). For decreased responses after glutamate (D), cultures with added astroglia show 5-fold more activity (P=0.008). For the small fraction of decreased responses after bicuculline (D), cultures with astroglia added have 2-fold higher activity than cultures without added astroglia (P=0.03). Cultures were 22–29 DIV.

Table 2.

Treatment-induced changes in activitya

| Increase (fold change) |

Decrease (fold change) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No glia added | Glia added | No glia added | Glia added |

| Initial to bicuculline | |||

| 2.9 (82%) | 1.5 (84%) | 0.5 (18%) | 0.6 (16%) |

| From bicuculline rinse to glutamate | |||

| 0.7 (71%) | 2.6 (76%) | 0.2 (29%) | 0.6 (24%) |

| From glutamate rinse to tetrodotoxin | |||

| 0.6 (69%) | 0.3 (77%) | 0.2 (31%) | 0.07 (23%) |

Changes in activity are separated into responses that either increase or decrease following the previous condition (or rinse). The fold change is (rate with drug) / (initial spike rate). Fold changes of <1 indicate decreases in activity. Figures in brackets are the percentage of active electrodes for each condition.

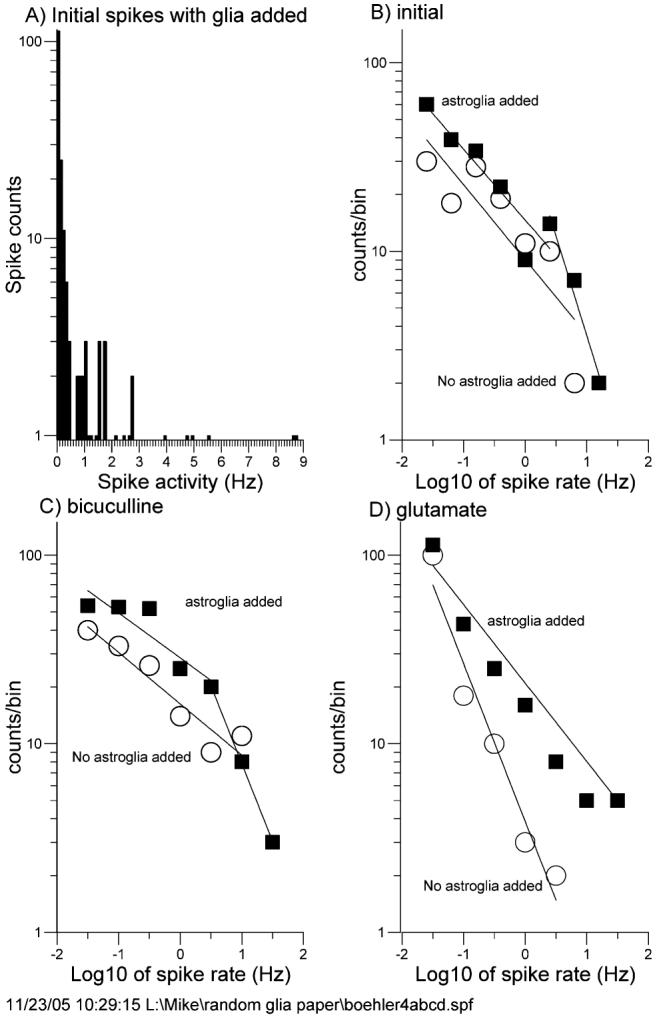

Fig. 4A shows the distribution of spike frequencies for initial rates with astroglia added. The non-Gaussian distribution renders common statistics inappropriate for comparing mean spike rates. However, it is instructive to plot the data on log–log axes to facilitate fitting with power law functions (Fig. 4B-D and Table 3). For all cases (Fig. 4B-D), the addition of astroglia increases the firing rates across the entire spectrum, causing the curves to shift up and to the right. For spontaneous activity (Fig. 4B) and bicuculline-induced activity (Fig. 4C) the slopes of the curves are similar over much of the range, with the addition of a more rapidly declining component at the highest frequencies only in cultures with added astroglia. For the glutamate-induced activity with added astroglia (Fig. 4D), the 53% less negative distribution slope indicates more neurons firing at every frequency class, with a few electrodes recording rates of 20 Hz (20-fold higher than rates attained in networks without added astroglia). These log–log distributions provide good fits to the activity data (Table 3) and allow comparisons between different conditions.

Fig. 4. Log–log distribution analysis of spike rates shows increased spike rates for added astroglia.

(A) Spike-frequency distribution shows a non-Gaussian peak with one tail. (B,C,D) Log–log distributions of networks without added astroglia (○) and with added astroglia (■) for initial condition (B), after bicuculline (C) and after glutamate (D). Parameters of regression-line fits are listed in Table 3. In all cases, cultures with added astroglia show a distribution shift to higher frequencies. Cultures were 22–29 DIV.

Table 3.

| Condition | Intercept | Slope | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | |||

| No added astroglia | 0.96 | −0.40 | 0.73 |

| Added astroglia | 1.16 | −0.38 | 0.85 |

| Second component | 1.61 | −1.06 | 0.97 |

| +bicuculline | |||

| No added astroglia | 1.21 | −0.27 | 0.90 |

| Added astroglia | 1.45 | −0.24 | 0.82 |

| Second component | 1.72 | −0.82 | 1.00 |

| +glutamate | |||

| No added astroglia | 0.59 | −0.84 | 0.96 |

| Added astroglia | 1.23 | −0.45 | 0.96 |

log(counts)=intercept + (slope) log (spike rate).

Effects of added astroglia on cell number

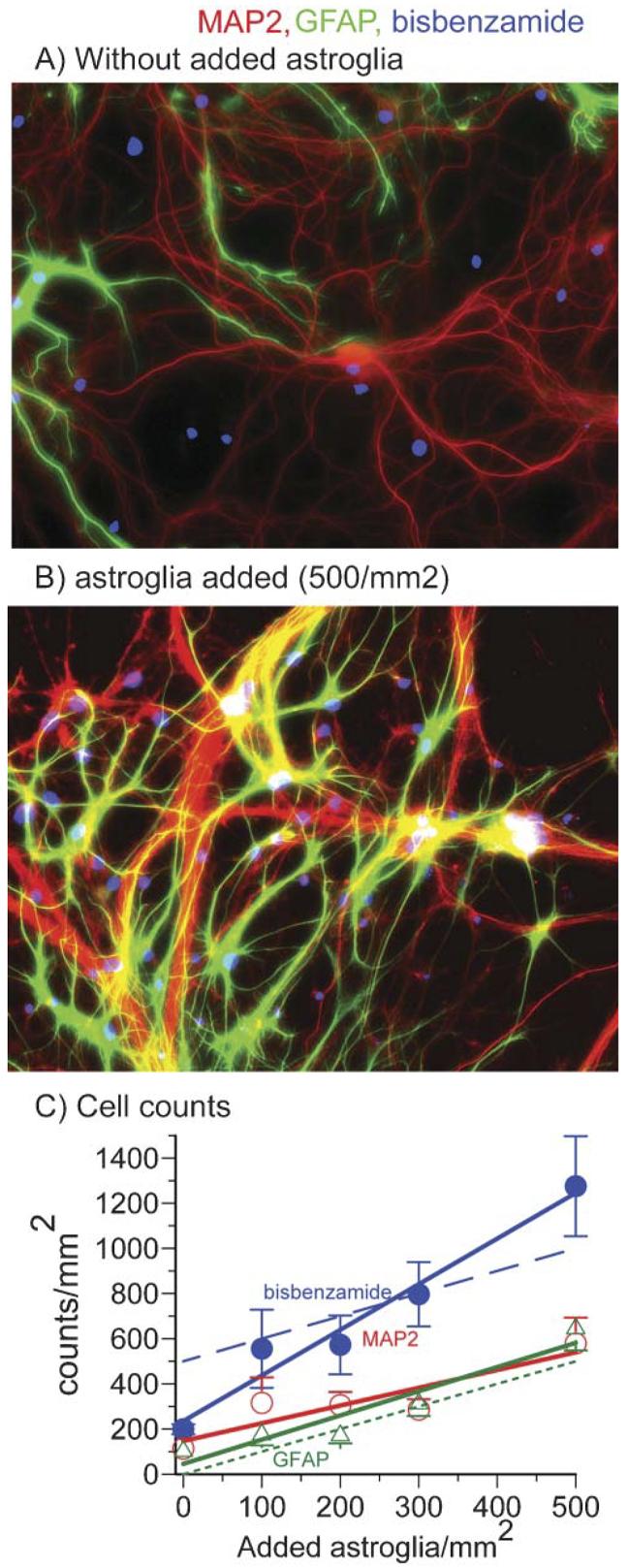

Questions about background levels of astroglia in control cultures, the relative survival of added astroglia and the impact of added astroglia on synapse density prompted us to probe cytoskeletal components as specific markers to distinguish neurons from astroglia. Generally, MAP2 is associated with somatodendritic regions of neurons (Caceres et al., 1984). GFAP is a common intermediate filament protein that is restricted to astroglia (Bignami et al., 1972). Synaptophysin was used to examine the density of synapses (Calhoun et al., 1996) and bisbenzamide to stain nuclei. Although hippocampal neuron cultures from E18 rats in Neurobasal/B27 medium plated at 160 cells mm−2 contain <1% astroglia out to 6 days in culture (Brewer et al., 1993), astroglial counts increase from ∼10% on day 8 to 20% of the cells on day 22 (data not shown). Fig. 5A shows noticeable immunoreactivity of astroglia after 22 days in culture. Without adding astroglia to the culture (0), Fig. 5C shows a mean density of 100 astroglia mm−2 and 100 neurons mm−2 after 22 days in culture.

Fig. 5. Added astroglia improves neuron survival.

(A,B) Immunostaining for astroglial GFAP (green) and neuronal MAP2 (red) after incubation for 22 days indicates more astroglia are present when (B) astroglia are added to the cultures than when (A) no astroglia were added. Nuclear staining with bisbenzamide appears blue. (C) Regression lines show the effect of adding increasing concentrations of astroglia on immunostaining of nuclei (bisbenzamide, ●), neurons (MAP2, ○) and astroglia (GFAP, △). Immunostaining by each increases as more astroglia are added. The dotted line is a theoretical result assuming no astroglia present when none were added. The dashed line is the theoretical total nuclei assuming all neurons survive and astroglia start at zero. Note that actual astroglial counts start at 100 after 22 days of culture not zero and bisbenzamide counts start at 200 after 22 days, not the 500 cells that were originally added.

Adding increasing numbers astroglia results in a higher population density of both astroglia and neurons after 22 days in culture (Fig. 5B,C). Comparing the number of astroglia counted after 2 weeks of growth indicates a good fit with the theoretical line of added astroglia with no proliferation (Fig. 5C). The total bisbenzamide staining of nuclei increases at a rate slightly greater than expected with added astroglia. This indicates that either astroglia or neurons might be undercounted because of either overlap or because oligodendrocytes have developed, but the effect is not significantly different from what is theoretically expected if 500 astroglia are added to 500 neurons mm−2 (500 neurons + 500 astroglia = 1000 nuclei). At this one-to-one ratio of cell types, both neurons and astroglia remain close to their original densities (Fig. 5C).

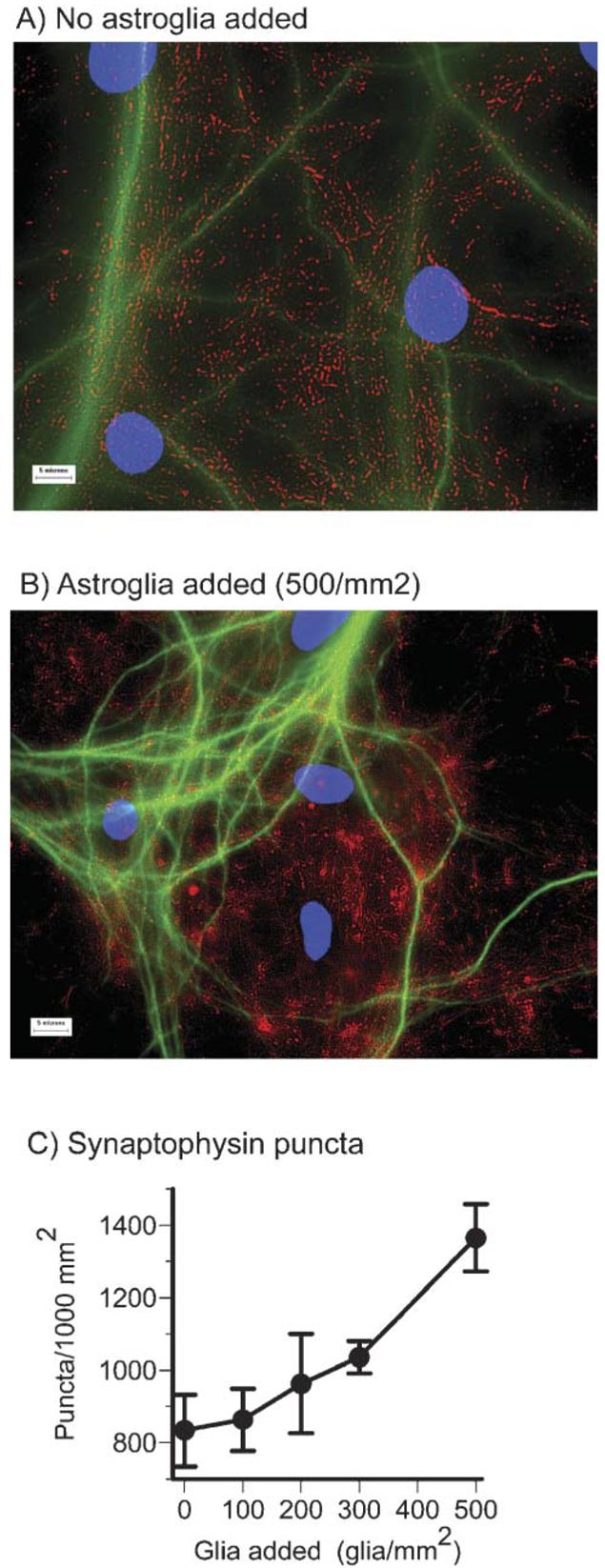

Effects of added astroglia and glia-conditioned medium on synaptophysin puncta

The increased activity noted above for cultures with added astroglia might be caused by an increased density of synapses. A culture to which astroglia were not added is immuno-reactive for synaptophysin, a protein found in presynaptic vesicles (Fig. 6A). Each punctum represents one or two close-proximity synapses. Fig. 6B shows a higher density of synaptophysin immunoreactive puncta in a culture to which astroglia were added in numbers equal to the neurons. Fig. 6C shows that the 1.9-fold activity increase associated with added astroglia correlates with a 1.7-fold increase in density of synaptophysin puncta (ANOVA, P=0.008). For cultures including glia-conditioned medium, synaptophysin puncta increased 1.3-fold (P=0.03).

Fig. 6. Added astroglia increase the density of synaptophysin puncta.

(A) The density of puncta immunostained with synaptophysin (red) and MAP2 (green) increases when astroglia are added (B). (C) The concentration of synaptophysin puncta increased by >70% as more astroglia were added (P=0.008). Scale bars, 5 μm. Cultures were 22–29 DIV.

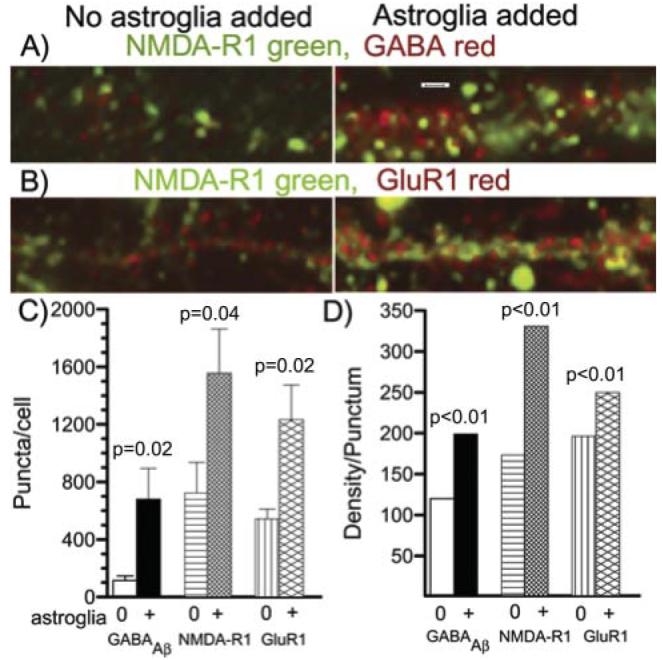

Effects of added astroglia on neurotransmitter receptor puncta

To determine whether an increase in the density of neurotransmitter receptors was associated with the higher firing rates and synaptic densities, we measured immuno-reactivity for the GABAAβ receptor, NMDA-R1 and Glu-R1 (AMPA receptor). Fig. 7A,B shows an increase in puncta number and density of immunolabel for each receptor measured with added astroglia. The intensity of fluorescent puncta extended over such a large range that digital segmentation required separation into bright and dim classes. The lower end of each class was determined empirically to maximize the number of objects counted, but was held constant for the immunoreactive images of each receptor type. Relative to cultures without added astroglia, quantitation of bright objects (Fig. 7C) indicates that the addition of astroglia produced a 6-fold increase in the density of GABAAβ receptor puncta per cell. Similar comparisons for NMDA receptor and AMPA receptor puncta indicated that both increased 2-fold. Analysis of dim puncta showed equivalent densities for GABA (1589±321, 1679±270, n.s.) and NMDA receptors (866±199, 1003±162, n.s.), for cells without and with astroglia added, respectively. The same comparison of dim AMPA receptors showed a significant 1.5-fold increase for cultures with astroglia added (1072±54, 1531±200, P=0.04). A combination of bright and dim puncta showed similar scaling of these three receptor types with addition of astroglia to produce a 1.6-fold increase in receptors per cell over that without added astroglia (2-factor split plot ANOVA, F(1,14)=5.8, P=0.03).

Fig. 7. Added astroglia increase transmitter receptor puncta density and clustering.

(A) NMDA-R1 (green) and GABAAβ (red) receptor immunostaining for a dendritic segment from a culture without added astroglia (left) or with added astroglia (right). Note the increase in both receptor numbers per linear distance and the intensity of each punctum (clustering of receptors) with added astroglia. Scale bar, 3 μm. (B) NMDA-R1 (green) and Glu-R1 (red) immunostaining for a dendritic segment from a culture without added astroglia (left) or with added astroglia (right). Again, both receptor numbers and their intensities increase with added astroglia. (C) Statistical evaluation of bright receptor puncta per cell (n=8 fields of 0.016 mm2 for each condition). Note significantly higher numbers of each receptor with added astroglia than without added astroglia. (D) Mean fluorescence intensity (density) of each punctum. Standard error bars are too small to see for the large number of each receptor type: for without, with added astroglia, GABA n=19885, 16000; NMDA n=11354, 9572; Glu-R1 n=26729, 16026. Each bar with added astroglia is significantly larger than the bar without added astroglia. Cultures were 22 DIV.

The increase in labeling intensity of each punctum (density/punctum) represents an increase in receptor clustering. The labeling intensity of each punctum of these receptors increased significantly (Fig. 7D). With added astroglia, receptor density/punctum for GABAAβ receptors increased 1.7-fold, whereas increases of 1.9-fold and 1.3-fold were apparent for NMDA-R1 and Glu-R1, respectively. These results indicate that added astroglia increase individual receptor clustering as well as total synapses per neuron.

CONCLUSIONS

Addition of astroglia to serum-free cultures of neurons on multi-electrode arrays

Increased spontaneous spike rates 2-fold, increased glutamate-stimulated spike rates 6-fold and eliminated desensitization.

Shifted the log–log distribution of spike rates on different electrodes to higher rates.

Was accompanied by an increase in neuron survival.

Increased the density of immunoreactive synaptophysin puncta by 1.7-fold, and the puncta density of receptors for GABA, NMDA and AMPA by 6-, 2- and 2-fold respectively. Combined with evidence of NMDA-receptor clustering, these observations indicate synaptic scaling.

Glia-conditioned medium mimics the changes observed with added astroglia except for responses to glutamate.

DISCUSSION

We have described a method for successfully adding astroglia to predominantly neuronal cultures under serum-free conditions so that astroglia do not multiply uncontrollably. Associated with this addition of astroglia were 1.9-fold higher spike rates, better neuron survival and a 1.7-fold greater density of synaptophysin puncta, 6-fold more GABAAβ, 2-fold more Glu-R1 and 2-fold more NMDA-R1 puncta, which indicates a higher density of synapses. The increased brightness of these puncta also indicate receptor clustering. These observations, together with the previously reported increase in presynaptic quantal content and a higher density of GluR2/3 receptors (Pfrieger and Barres, 1997) might be caused by several mechanisms. First, the high-capacity glutamate(Bergles and Jahr, 1998) and GABA- (Chatton et al., 2003) uptake systems in astroglia with processes in proximity to synapses would decrease the synaptic dwell times of either glutamate or GABA released into the synapse. This alone might increase spike rates, enabling faster signaling and reducing neuronal glutamate excitotoxicity (Rosenberg et al., 1992). However, the finding that addition of glia-conditioned medium reproduced all but the glutamate-stimulated effects indicates that diffusible trophic factors released by astroglia promote the baseline increases in spike rates. Higher neuron densities that we observed in association with added astroglia are likely to result from this decreased excitotoxicity and from trophic factors that are released by astroglia and promote neuronal survival. Mauch et al. (2001) showed that cholesterol produced by astroglia added to cultures of retinal ganglion neurons contributes to an increased quantal content, a higher density of synapsin puncta, an increased EPSC frequency and a decrease failure rate at synapses. Thrombospondin, an extracellular matrix protein, is another neurotrophic factor released by astroglia that promotes synaptogenesis (Christopherson et al., 2005). Evidence that these astroglial contributions diffuse comes from the efficacy of medium conditioned by astroglial cultures in place of the astroglia themselves. These astroglial contributions create more robust synapses.

An increase in spontaneous spike rates might also be achieved by either increased presynaptic release of glutamate or postsynaptic decreases in inhibitory receptors and/or increases in excitatory receptor function. Turrigiano has reported several mechanisms that coordinately regulate synaptic activity, a process termed synaptic scaling or homeostatic plasticity. In adult stomatogastric ganglion neurons in culture, a change from tonic to bursting action potentials is accompanied by changes in the ratio of inward:outward currents (Turrigiano et al., 1995). Deprivation of visual cortical activity downregulates GABAergic input through reduced BDNF (Rutherford et al., 1997); but BDNF-independent mechanisms also control quantal current amplitudes through postsynaptic polarization (Leslie et al., 2001). Even the ratio of two inward currents, AMPA and NMDA, are scaled together with activity changes to keep a constant receptor ratio (Watt et al., 2000). Further comparisons of Glu-R1 and Glu-R2 with presynaptic mechanisms indicate a predominant effect of activity blockage on the postsynaptic receptors without evidence for changes in quantal glutamate content or release (Wierenga et al., 2005). Another example of homeostatic scaling in hippocampal slice cultures was observed as upregulation of inhibitory parvalbumin puncta (but not GABAA1 protein) together with excitatory Glu-R1 and NMDA-R1 following inhibition of excitatory receptors with 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2, 3-dione (CNQX) and 2-amino-5-phosphopentanoic acid (AP5) (Buckby et al., 2006). Thus, in our studies with added astroglia, the increases in GABAAβ inhibitory receptors and Glu-R1 and NMDA-R1 excitatory receptors that we observed by immunocytology is another example of synaptic scaling. The slightly larger increase in total number of excitatory receptors (Glu-R1 and NMDA-R1) and their clustering with added astroglia might explain the higher firing rates with added astroglia that is not mimicked completely with glia-conditioned medium.

The receptor clustering that we observed in response to added astroglia has been observed previously with several stimuli and is often associated with increased postsynaptic currents. Elmariah et al. (2004) found GABAA receptor clustering in response to BDNF through Trk-B receptors. Astroglia that we added are also known to produce BDNF in response to activity-dependent trans-synaptic signals from prostaglandins (Toyomoto et al., 2004). Together with integrin-mediated astroglial adhesion to neurons, these prostaglandins activate protein kinase C signaling in neurons and excitatory synaptogenesis (Hama et al., 2004). Craig et al. (1994) were the first to demonstrate Glu-R1 and GABAA receptors opposite their transmitter-release sites. AMPA-receptor clustering is induced by activity-dependent Narp (O'Brien et al., 1999). Cottrell et al. (2000) showed that GluR1 and NMDA-R1 receptors cluster from extrasynaptic sites as synapses mature in culture. Wang et al. (2005) have reviewed the role of phosphorylation in receptor clustering. Here, we show that astroglia enable this clustering with functional increases in spontaneous and stimulated spike rates.

In addition to these effects of astroglia on neurons, increasing evidence supports a dynamic role for astroglia in normal and dysfunctional brains (Seifert et al., 2006). The glucose–lactate shuttle between astrocytes and neurons enables more efficient energy handling (Pellerin et al., 1998) because synapse distance varies from the capillary supply of glucose and removal of lactate, but astrocytes maintain close contact to capillaries in vivo. Most intriguing is the recent discovery of synaptic transmission onto astroglia through astroglial Glu-R1 (AMPA) receptors and GABAA receptors (Jabs et al., 2005). Although they found up to four synaptic events per minute (0.07 Hz), no action potentials were reported that would be necessary to account for the increased spike rates detected in our extracellular recordings. However, astrocytic neurotransmitter synapses do indicate a more intimate relationship of neuronal activity with astroglial metabolism than is widely appreciated.

Generally, we observed an expected increase in spike rates following addition of the GABAA antagonist bicuculline (Dunn and Thuynsma, 1994). However, 16–18% of the neurons in our networks showed a decrease in spike activity, which was unaffected by addition of astroglia. This change that we observed in the hippocampal neural networks is supported by the work of Li et al. (1998) who studied maturation of chloride gradients in spinal cord neurons. Activation of GABAA receptor Cl− channels uniformly depolarized embryonic neurons but hyperpolarized adult neurons. This homeostasic switch (Miles, 1999) depends on the Cl− gradient of the cell, which, in turn, is controlled by developmental regulation of the K+/Cl− co-transporter (Rivera et al., 1999). These principles explain why we observed increases in spike rates after bicuculline in ∼80% of the neurons while a lower spike rate was elicited in ∼20% of the neurons (Table 2). In response to bicuculline, spike rates increased more in cultures without added astroglia to equal the spike rates for neurons with added astroglia. This indicates that the cultures without added astroglia were more strongly inhibited before the addition of bicuculline (see next paragraph also). For spike rates that decreased from resting levels in response to bicuculline, rates were 2-fold higher with added astroglia than without, indicating more spontaneous excitatory stimuli remain even in the presence of blocked endogenous GABA-mediated depolarization.

The extracellular field potentials recorded by our substrate-based electrodes do not distinguish between excitatory and inhibitory currents, which is possible in pairs of intracellular recordings (Vogt et al., 2005). We observed 62% inhibitory connections and 38% excitatory, a ratio of 1.6. Rimvall and Martin (1991) and Ma et al. (1998) also observed a preponderance of inhibitory synapses in their cultures. From our numbers of active electrodes following treatment with either bicuculline or glutamate without added astroglia, we infer a ratio of inhibitory to excitatory neurons of 4.6 (Fig. 3C, 55/12=4.6). With added astroglia, this ratio drops to 2.0 (102/50). These data indicate that, without added astroglia, a higher fraction of inhibitory neurons are necessary to keep the network from becoming spontaneously hyperactive. The additional glutamate-uptake capacity with added astroglia enables 4-fold more excitatory synapses. In the absence of sufficient astroglia, glutamate receptors either might desensitize faster (Sun et al., 2002), as indicated in Fig. 2C, or cause excitotoxicity, as indicated by Fig. 5C, with less neuron survival without added astroglia. If initial responses of receptor desensitization and more inhibitory receptors are not sufficient to control overactivity, then excitotoxicity is likely. By contrast, the spreading increase in activity throughout the network with added astroglia over a 30-sec period for low doses of glutamate (Fig. 2C) indicates the ability to accept and propagate these higher spike rates.

The non-Gaussian, power-law distribution of spike activity that was observed consistently indicates Levy distributions, which several investigators have attributed to non-linearly coupled physiological processes (Peng et al., 1993; Goldberger et al., 1990), which were recognized first in neuronal networks for interspike intervals by Segev et al. (2002). The near-linear accommodation of our electrodes that were inactive when recoded from 0 to 0.016 Hz indicates that a longer recording time might reveal more active electrodes of low activity. Although the spike-frequency distributions are similar for initial rates either without or with added astroglia, the distribution analysis identifies a higher rate class of neurons for cultures with added astroglia. This higher rate class for added astroglia is also seen after exposure to bicuculline. In cultures without added astroglia, the addition of glutamate eliminates the lower slope response type, converting the network to the higher slope type. This conversion was described previously, both theoretically (Latham et al., 2000a) and experimentally (Latham et al., 2000b), in terms of transition from a small fraction of endogenously active cells in a bursting network to a larger fraction of activity that produces the more steady firing that we see after glutamate stimulation, especially the higher rates in networks with added astroglia. Waagenar et al. (2005) also find less bursting with more stimulation of the network.

Some methodological considerations should be emphasized. Typically, astroglia are cultured in a serum-containing medium. When harvested directly from this medium and applied to neurons in serum-free medium, both neurons and astrocytes died. By simple adaptation of the astroglia to a 50% medium change in serum-free medium, astroglia survived well and stopped proliferating. Although the addition of astroglia on day 8 is an unphysiological manipulation, it demonstrates the principal of an active role of astroglia in synapse formation and increased spike rates. Because lower levels of astroglia already exist on day 8, perhaps the transition to a higher density was better accommodated. Without this addition, the lower levels of astroglia without serum indicates that some growth factors, such as from the in vivo bloodstream contribute to the coordinate proliferation of astroglia as neurons mature. The observation that spike activity increased indicates that the added astroglia did not significantly occlude electrodes from their contact with neurons. Another issue of cell density of 500 cells mm−2 might be considered high for many studies using intracellular recording, but is much lower than in the brain and lower than the 1000–2500 cells mm−2 used by Potter's group (Wagenaar et al., 2005; Wagenaar et al., 2006).

In conclusion, the addition of astroglia at concentrations equal to the neuronal density promotes higher spontaneous network spike rates as well as higher rates in response to glutamate and higher fractions of active electrodes. The resulting higher density of synapses is a consequence of several aspects of astroglial physiology, including high-capacity glutamate- and GABA-uptake, release of trophic factors, and a higher number of synapses with GABA and glutamate receptors as well as receptor clustering.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank John Torricelli for assistance with cell isolations and C. Nick Fogleman and Adelle Maynard for data analysis. This work was supported in part by NSF EIA 01328, NIH AG-13435 NIH RO1-EB00786 and RO1-NS522331.

REFERENCES

- Abney ER, Bartlett PP, Raff MC. Astrocytes, ependymal cells, and oligodendrocytes develop on schedule in dissociated cell cultures of embryonic rat brain. Developmental Biology. 1981;83:301–310. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banker GA. Trophic interactions between astroglial cells and hippocampal neurons in culture. Science. 1980;209:809–810. doi: 10.1126/science.7403847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbin G, Pollard H, Gaiarsa JL, Ben Ari Y. Involvement of GABAA receptors in the outgrowth of cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience Letters. 1993;152:150–154. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90505-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JL, Bahar TN, Ma W, Maric D, Maric I. GABA emerges as a developmental signal during neurogenesis of the rat central nervous system. In: Martin DL, Olsen RW, editors. GABA in the Nervous System. Lippincott Williams and Wilkens; 2000. pp. 245–263. [Google Scholar]

- Bergles DE, Jahr CE. Glial contribution to glutamate uptake at Schaffer collateral-commissural synapses in the hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:7709–7716. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07709.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignami AE, Eng LF, Dahl D, Uyeda CT. Localization of the glial fibrillary acidic protein in astrocytes by immunofluorescence. Brain Research. 1972;43:429–435. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Torricelli JR, Evege EK, Price PJ. Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1993;35:567–576. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490350513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckby LE, Jensen TP, Smith PJ, Empson RM. Network stability through homeostatic scaling of excitatory and inhibitory synapses following inactivity in CA3 of rat organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2006;31:805–816. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres A, Banker G, Steward O, Binder L, Payne M. MAP2 is localized to the dendrites of hippocampal neurons which develop in culture. Developmental Brain Research. 1984;13:314–318. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun ME, Jucker M, Martin LJ, Thinakaran G, Price DL, Mouton PR. Comparative evaluation of synaptophysin-based methods for quantification of synapses. Journal of Neurocytology. 1996;25:821–828. doi: 10.1007/BF02284844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatton JY, Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ. GABA uptake into astrocytes is not associated with significant metabolic cost: implications for brain imaging of inhibitory transmission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. 2003;100:12456–12461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132096100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chih B, Engelman H, Scheiffele P. Control of excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation by neuroligins. Science. 2005;307:1324–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.1107470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson KS, Ullian EM, Stokes CC, Mullowney CE, Hell JW, Agah A, et al. Thrombospondins are astrocyte-secreted proteins that promote CNS synaptogenesis. Cell. 2005;120:421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell JR, Dube GR, Egles C, Liu G. Distribution, density, and clustering of functional glutamate receptors before and after synaptogenesis in hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;84:1573–1587. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AM, Blackstone CD, Huganir RL, Banker G. Selective clustering of glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors opposite terminals releasing the corresponding neurotransmitters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. 1994;91:12373–12377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn SM, Thuynsma RP. Reconstitution of purified GABAA receptors: ligand binding and chloride transporting properties. Biochemistry. 1994;33:755–763. doi: 10.1021/bi00169a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmariah SB, Crumling MA, Parsons TD, Balice-Gordon RJ. Postsynaptic TrkB-mediated signaling modulates excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter receptor clustering at hippocampal synapses. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:2380–2393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4112-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberger AL, Rigney DR, West BJ. Chaos and fractals in human physiology. Scientific American. 1990;262:42–49. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0290-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross GW. Simultaneous single unit recording in vitro with a photoetched laser deinsulated gold multimicroelectrode surface. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 1979;26:273–279. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1979.326402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama H, Hara C, Yamaguchi K, Miyawaki A. PKC signaling mediates global enhancement of excitatory synaptogenesis in neurons triggered by local contact with astrocytes. Neuron. 2004;41:405–415. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs R, Pivneva T, Huttmann K, Wyczynski A, Nolte C, Kettenmann H, et al. Synaptic transmission onto hippocampal glial cells with hGFAP promoter activity. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118:3791–3803. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefer EW, Norton SJ, Boyle NA, Talesa V, Gross GW. Acute toxicity screening of novel AChE inhibitors using neuronal networks on microelectrode arrays. Neurotoxicology. 2001;22:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(00)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester HJ, Johnston D. Target cell-dependent normalization of transmitter release at neocortical synapses. Science. 2005;308:863–866. doi: 10.1126/science.1100815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham PE, Richmond BJ, Nelson PG, Nirenberg S. Intrinsic dynamics in neuronal networks. I. Theory. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000a;83:808–827. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.2.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham PE, Richmond BJ, Nirenberg S, Nelson PG. Intrinsic dynamics in neuronal networks. II. experiment. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000b;83:828–835. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.2.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie KR, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Postsynaptic depolarization scales quantal amplitude in cortical pyramidal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(RC170):1–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-j0005.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YX, Schaffner AE, Walton MK, Barker JL. Astrocytes regulate developmental changes in the chloride ion gradient of embryonic rat ventral spinal cord neurons in culture. Journal of Physiology. 1998;509:847–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.847bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Schaffner A, Chang Y, Barker JL. Astrocyte-conditioned saline supports embryonic rat hippocampal neuron differentiation in short-term cultures. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1998;86:71–77. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Liu QY, Jung D, Manos P, Pancrazio JJ, Schaffner AE, et al. Central neuronal synapse formation on micropatterned surfaces. Developmental Brain Research. 1998;111:231–243. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauch DH, Nagler K, Schumacher S, Goritz C, Muller EC, Otto A, et al. CNS synaptogenesis promoted by glia-derived cholesterol. Science. 2001;294:1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5545.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles R. Neurobiology. A homeostatic switch. Nature. 1999;397:215–216. doi: 10.1038/16604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien RJ, Xu D, Petralia RS, Steward O, Huganir RL, Worley P. Synaptic clustering of AMPA receptors by the extracellular immediate-early gene product Narp. Neuron. 1999;23:309–323. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak JL, Wheeler BC. Two-dimensional current source density analysis of propagation delays for components of epileptiform bursts in rat hippocampal slices. Brain Research. 1989;497:223–230. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin L, Pellegri G, Martin JL, Magistretti PJ. Expression of monocarboxylate transporter mRNAs in mouse brain: support for a distinct role of lactate as an energy substrate for the neonatal vs. adult brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the U.S.A. 1998;95:3990–3995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C-K, Mietus J, Hausdorff J, Havlin S, Stanlye H, Goldberger AL. Long-Range anticorrelations and non-Gaussian behavior of the heartbeat. Physical Review Letters. 1993;70:1343–1346. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfrieger FW, Barres BA. Synaptic efficacy enhanced by glial cells in vitro. Science. 1997;277:1684–1687. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine J. Recording action potentials from cultured neurons with extracellular microcircuit electrodes. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1980;2:19–31. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(80)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt KG, Watt AJ, Griffith LC, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Activity-dependent remodeling of presynaptic inputs by postsynaptic expression of activated CaMKII. Neuron. 2003;39:269–281. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimvall K, Martin DL. GAD and GABA in an enriched population of cultured GABAergic neurons from rat cerebral cortex. Neurochemical Research. 1991;16:859–868. doi: 10.1007/BF00965534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C, Voipio J, Payne JA, Ruusuvuori E, Lahtinen H, Lamsa K, et al. The K+/Cl− co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature. 1999;397:251–255. doi: 10.1038/16697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg PA, Amin S, Leitner M. Glutamate uptake disguises neurotoxic potency of glutamate agonists in cerebral cortex in dissociated cell culture. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:56–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-01-00056.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford LC, DeWan A, Lauer HM, Turrigiano GG. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor mediates the activity-dependent regulation of inhibition in neocortical cultures. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:4527–4535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04527.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev R, Benveniste M, Hulata E, Cohen N, Palevski A, Kapon E, et al. Long term behavior of lithographically prepared in vitro neuronal networks. Physical Review Letters. 2002;88:118102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.118102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert G, Schilling K, Steinhauser C. Astrocyte dysfunction in neurological disorders: a molecular perspective. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:194–206. doi: 10.1038/nrn1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidl EM, Neveu E, Bertrand D, Buisson B. The adult rat hippocampal slice revisited with multi-electrode arrays. Brain Research. 2006;1096:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Olson R, Horning M, Armstrong N, Mayer M, Gouaux E. Mechanism of glutamate receptor desensitization. Nature. 2002;417:245–253. doi: 10.1038/417245a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CA, Jr., Springer PA, Loeb GE, Berwald-Netter Y, Okun LM. A miniature microelectrode array to monitor the bioelectric activity of cultured cells. Experimental Cell Research. 1972;74:61–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(72)90481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyomoto M, Ohta M, Okumura K, Yano H, Matsumoto K, Inoue S, et al. Prostaglandins are powerful inducers of NGF and BDNF production in mouse astrocyte cultures. FEBS Letters. 2004;562:211–215. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano G, LeMasson G, Marder E. Selective regulation of current densities underlies spontaneous changes in the activity of cultured neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:3640–3652. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03640.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullian EM, Sapperstein SK, Christopherson KS, Barres BA. Control of synapse number by glia. Science. 2001;291:657–661. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5504.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt AK, Brewer GJ, Decker T, Bocker-Meffert S, Jacobsen V, Kreiter M, et al. Independence of synaptic specificity from neuritic guidance. Neuroscience. 2005;134:783–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar DA, Madhavan R, Pine J, Potter SM. Controlling bursting in cortical cultures with closed-loop multi-electrode stimulation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:680–688. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4209-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar DA, Pine J, Potter SM. An extremely rich repertoire of bursting patterns during the development of cortical cultures. BMC Neuroscience. 2006;7:11–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, Arora A, Yang L, Parelkar NK, Zhang G, Liu X, et al. Phosphorylation of AMPA receptors: mechanisms and synaptic plasticity. Molecular Neurobiology. 2005;32:237–249. doi: 10.1385/MN:32:3:237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt AJ, van Rossum MC, MacLeod KM, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Activity coregulates quantal AMPA and NMDA currents at neocortical synapses. Neuron. 2000;26:659–670. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga CJ, Ibata K, Turrigiano GG. Postsynaptic expression of homeostatic plasticity at neocortical synapses. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:2895–2905. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5217-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyart C, Ybert C, Bourdieu L, Herr C, Prinz C, Chatenay D. Constrained synaptic connectivity in functional mammalian neuronal networks grown on patterned surfaces. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2002;117:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]