Abstract

Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) potently stimulates intestinal growth. Insulinreceptorsubstrate-1(IRS-1)mediates proliferative and antiapoptotic actions of IGF-I in cell lines, but its in vivo relevance in intestine is not defined. This study tested the hypothesis that there is cell type-specific dependence on IRS-1 as a mediator of IGF-I action. Length, mass, crypt cell proliferation, and apoptosis were measured in small intestine and colon of IRS-1-null mice and wild-type (WT) littermates and in colon of IRS-1-null or WT mice expressing IGF-I transgenes. Expression of IGF-I receptor and signaling intermediates was examined in intestine of WT and IRS-1-null mice, cultured intestinal epithelial cells, and myofibroblasts. Absolute IRS-1 deficiency reduced mucosal mass in jejunum and colon, but effects were more pronounced in colon. Muscularis mass was decreased in both segments. In IGF-I transgenics, IRS-1 deficiency significantly attenuated IGF-I-stimulated growth of colonic mucosa and abolished antiapoptotic but not mitogenic effects of IGF-I transgene on crypt cells. IGF-I-induced muscularis growth was unaffected by IRS-1 deficiency. In intestinal epithelial cells, IRS-1 was expressed at higher levels than IRS-2 and was preferentially activated by IGF-I. In contrast, IGF-I activated both IRS-1 and IRS-2 in intestinal myofibroblasts and IRS-2 activation was upregulated in IRS-1-null myofibroblasts. We conclude that the intestinal epithelium but not the muscularis requires IRS-1 for normal trophic actions of IGF-I and that IRS-1 is required for antiapoptotic but not mitogenic effects of IGF-I in the intestinal crypts in vivo.

Systemic insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) potently increases growth of the small intestine and colon, and elevated circulating IGF-I increases the risk of intestinal cancer (7). Studies in transgenic mice that overexpress IGF-I demonstrate both endocrine and local autocrine or paracrine actions of IGF-I on bowel growth in vivo (15, 16, 25, 28). Mice that overexpress a human IGF-I transgene driven by a mouse metallothionein-1 promoter (MT-hIGF-I transgenics) exhibit significant increases in small bowel length, mass of small bowel mucosa, and crypt cell proliferation (15). These effects may derive from endocrine effects of the elevated circulating IGF-I that occur in this model or from autocrine or paracrine actions of transgene-derived IGF-I, which is locally overexpressed in intestine of these mice (15). SMP8-IGF-I transgenic mice have a rat IGF-I transgene driven by the smooth muscle α-actin SMP8 promoter. These mice have normal plasma levels of IGF-I but show high-level expression of the IGF-I transgene specifically in enteric smooth muscle layers, leading to overgrowth of muscularis layers (25, 28).

The type 1 IGF receptor (IGF-IR) is the primary mediator of the growth-promoting effects of IGF-I in vitro and in vivo (3). The IGF-IR is a receptor tyrosine kinase and is expressed throughout the intestine (11, 21). IGF-I induces autophosphorylation of the IGF-IR and subsequent, rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of several early intracellular signaling proteins, including insulin receptor substrates (IRS-1 and IRS-2) and Src homology 2 domain and collagen protein (Shc) (3, 13). Considerable in vitro evidence, derived largely from embryonic or cancer cell lines, indicates that IRS-1 is a major intracellular mediator of the proliferative and antiapoptotic actions of IGF-I (2, 3). Mice that are homozygous for IRS-1 gene deletion (IRS-1−/−) exhibit reduced body weight and reduced weight of a number of organs, but the magnitude of growth impairment differs among organs (16). In IRS-1-null mice, the weight of the small intestine is preserved more than body weight or the weight of the gastrocnemius muscle but is impaired more than brain weight (16). The intermediate growth dependence of the small intestine on IRS-1 prompted us to analyze intestinal growth in IRS-1-null mice in more detail to test the hypothesis that there are cell type-specific differences in the requirement for IRS-1 as an in vivo mediator of intestinal growth. We therefore examined growth of the mucosa and muscularis in the small intestine and colon of IRS-1-null mice and wild-type (WT) littermates.

Intestinal growth deficits in IRS-1-null mice may reflect impaired actions of IGF-I but could reflect impaired actions of other hormones that utilize IRS-1 as a signaling intermediate, including insulin or growth hormone (3, 16). IGF-I transgenic mice cross-bred with IRS-1-null mice provide a useful model to directly assess whether the growth-promoting effects of IGF-I on the intestinal mucosa or muscularis layers in vivo require IRS-1. We therefore examined growth of colonic mucosa and muscularis layers in MT-hIGF-I transgenic or SMP8-IGF-I transgenic mice that have two functional IRS-1 alleles (IRS-1+/+) or are homozygous for IRS-1 gene disruption (IRS-1−/−). We focused our analyses on colon because initial studies in IRS-1-null mice revealed major growth deficits in both mucosa and muscularis layers of the colon. In addition, despite considerable evidence for a role of IGF-I in colorectal cancer (5), surprisingly little is known about the in vivo actions of IGF-I in normal colon or its mechanisms of action. Our findings provide novel evidence that IRS-1 deficiency impairs IGF-I action on the intestinal mucosa but not the muscularis. Moreover, we show that in vivo antiapoptotic but not proliferative actions of IGF-I on the crypt epithelium require IRS-1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

IRS-1−/−, IRS-1+/−, and IRS-1+/+ mice

Founder mice heterozygous for targeted disruption of the IRS-1 gene (1) were provided by C. Ronald Kahn (Joslin Diabetes Center, Boston, MA). IRS-1+/− males and females were bred to generate mice with zero copies (IRS-1−/−), one copy (IRS-1+/−), or two copies (IRS-1+/+) of the IRS-1 gene. Genotypes were identified by PCR on tail DNA as previously described (1, 16). Analyses focused on mice with zero or two copies of the IRS-1 gene, because previous studies indicate only very small intestinal growth deficits in IRS-1+/− mice (16). IRS-1−/− mice were compared directly with IRS-1+/+ littermates to eliminate interlitter variation.

WT and IGF-I transgenic mice with zero or two copies of the IRS-1 gene

Transgenic mice with germline integration of a human IGF-I transgene driven by the mouse metallothionein-1 promoter (MT-hIGF-I) were generated in our laboratories (15). Cross-breeding of IGF-I transgenics and mice with IRS-1 deficiency has been described in detail previously (16). MT-hIGF-I and WT mice with zero or two functional IRS-1 alleles were analyzed. All mice were given 25 mM zinc sulfate in drinking water to ensure maximal expression of the metallothionein promoter-driven IGF-I transgene in MT-hIGF-I transgenics. Genotype of cross-bred animals was established by PCR on tail DNA (1, 16). SMP8-IGF-I transgenic hemizygous males (25) were bred with IRS-1+/−/WT females to generate mice that were IRS-1+/− and hemizygous for the SMP8-IGF-I transgene (IRS-1+/−/SMP8-IGF-I). These mice were then bred with IRS-1+/−/WT mice to yield WT or SMP8-IGF-I mice with zero, one, or two functional IRS-1 alleles. IRS-1 genotype was identified by PCR on tail DNA. SMP8-IGF-I transgenic mice and WT mice were identified by Southern blotting on tail DNA as described previously (25). All studies were performed in adult 50- to 60-day-old mice.

Assays of bowel growth mass, histology, and crypt cell proliferation

Animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital (100 μg/g body wt). Small intestine was dissected from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal valve, the entire colon excluding the cecum was dissected, and the length and weight were recorded. Corresponding segments of jejunum and colon were collected for more-detailed analyses.

Protein, DNA content, and sucrase activities were assayed as previously described (15, 22). Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of jejunum and colon were examined qualitatively to complement the biochemical assays. Crypt cell mitoses were measured directly in microdissected whole crypts prepared from jejunum and colon by established methods (15, 22). The numbers of mitotic cells per crypt were assayed on 20 well-oriented crypts for each specimen by a single investigator who was unaware of the animal groupings. Apoptosis was assessed by morphological assays that have been verified to yield data equivalent to other methods such as terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP-mediated nick-end labeling (27). Myocyte density in muscularis layers was assayed by counting nuclei per unit area (1,000 μm2) on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections.

Expression of IGF-I signaling molecules in the intestine

Mucosal scrapings and muscularis layers from jejunum and colon were homogenized in extraction buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH = 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 100 mM NaF, 1.5% Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA) plus protease inhibitors (2 mM PMSF, 20 μg/ml aprotinin) and phosphatase inhibitor (2 mM Na3VO4). Protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for the IGF-IR β-chain (SC713; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), IRS-1 [JD-288 (1), SC-559, SC-560; Santa Cruz], IRS-2 [JD-250 (1), SC-8298; Santa Cruz], or Shc (SC-1695; Santa Cruz). Immunoprecipitates were electrophoresed on 8.5% (IGF-IR, IRS-1, and IRS-2) or 12% (Shc) SDS polyacrylamide gels and were transferred to PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA). Immunoblots were probed with IGF-IR, IRS-1, IRS-2, or Shc antibodies. Immunoreactive proteins were identified by using the ECL detection system (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) and published methods (1, 19). Abundance of immunoprecipitated proteins was quantified by using ImageQuant (version 1.2; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) software analysis of autoradiographs.

In vitro analyses

IEC-6, a nontransformed intestinal epithelial cell line from rat small intestine, was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, cultured as previously described, and used at passages 12–20 (19). Primary cultures of intestinal myofibroblasts were prepared from IRS-1+/+ and IRS-1−/− mice as previously described (24). Myofibroblast phenotype was confirmed by immunoblotting for α-smooth muscle actin and vimentin (18). Subconfluent myofibroblasts were studied at passages 4–6. IEC-6 cells or intestinal myofibroblasts were serum deprived for 24 h before treatment with IGF-I to analyze early signaling intermediates. Analyses of IRS-1, IRS-2, and Shc were performed by using immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting as described in Expression of IGF-I signaling molecules in the intestine. Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were detected by using anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies (4G10, Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY and PY20, Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA).

Data analysis and statistics

Values are expressed as means ± SE. Absolute values for bowel mass in IRS-1−/− and IRS-1+/+ littermates were compared by the Mann-Whitney U-test as independent groups. In addition, values in each IRS-1−/− mouse were expressed as a ratio of the corresponding value in a sex-matched littermate pair. Mean ratios for different measurements of intestinal growth were compared for a significant difference from 1 by using Wilcoxon signed-rank analyses or from each other by using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Mean measurements of bowel growth (bowel weight, length, DNA, protein, mitoses, and apoptosis) in IGF-I transgenics with different IRS-1 genotype were analyzed by two-factor ANOVA for significant main effects of IRS-1 gene deletion or the IGF-I transgene and for an interaction between IRS-1 gene deletion and IGF-I transgene. A significant interaction between IRS-1 gene deletion and IGF-I transgene provides statistical evidence that IRS-1 deficiency influences the magnitude of IGF-I-induced growth. Tukey’s test was used for post hoc, pair-wise comparisons between IGF-I transgenic and WT mice of each IRS-1 genotype or comparison between IRS-1−/−/WT and IRS-1+/+/WT mice. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Study protocols were in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health.

RESULTS

Effects of absolute IRS-1 deficiency on growth of jejunum and colon

Compared with IRS-1+/+ littermates, IRS-1−/− mice exhibited markedly reduced body weight (58 ± 5% of WT littermates; P < 0.01) and decreased weight and length of entire small intestine and colon (Table 1). More detailed analyses demonstrated reduced DNA content in the jejunal mucosa (63 ± 7% of IRS-1+/+ littermates), whereas mucosal wet weight, protein content, and sucrase activity were unaffected by IRS-1 deficiency (Table 2A). Crypt mitoses were reduced in the jejunal mucosa of IRS-1−/− mice (1.9 ± 0.15) relative to IRS-1+/+ mice (vs. 3.0 ± 0.17; P < 0.05). In jejunal muscularis, wet weight, protein content, and DNA content were all significantly decreased in IRS-1−/− mice compared with IRS-1+/+ littermates (Table 2A).

Table 1.

Effects of absolute IRS-1 deficiency on weight, length, and weight per unit length of the small intestine and colon

| Weight, g | Length, cm | Weight per Unit Length, mg/cm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Intestine | |||

| IRS-1+/+ | 1.29±0.07 | 43.63±0.71 | 30.45±1.45 |

| IRS-1−/− | 0.92±0.03* | 39.04±1.23* | 24.04±1.72* |

| Colon | |||

| IRS-1+/+ | 0.35±0.3 | 10.3±0.22 | 33.8±2.7 |

| IRS-1−/− | 0.22±0.01* | 8.9±0.24# | 24.4±4* |

Data are means ± SE of absolute values from at least 6 insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1−/− and IRS-1+/+ littermate pairs.

P < 0.05 between IRS-1+/+ and IRS-1−/− mice;

P = 0.066.

Table 2.

Mass of mucosa and muscularis layers of jejunum and colon in wild-type and IRS-1-null mice

| Genotype | Wet Weight, mg/cm | Protein, mg/cm | DNA, mg/cm | Protein/DNA Ratio | Sucrase Activity, U/cm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Jejunum | ||||||

| Mucosa | IRS-1+/+ | 36.0±2.00 | 4.68±0.39 | 0.13±0.01 | 38.80±4.89 | 0.25±0.02 |

| IRS-1−/− | 35.1±2.00 | 4.71±0.52 | 0.08±0.01* | 63.03±8.28* | 0.23±0.02 | |

| Muscularis | IRS-1+/+ | 11.7±0.40 | 1.69±0.13 | 0.15±0.01 | 11.31±1.02 | |

| IRS-1−/− | 7.6±0.30* | 0.88±0.05* | 0.07±0.01* | 14.08±1.27 | ||

| B: Colon | ||||||

| Mucosa | IRS-1+/+ | 40.2±2.30 | 6.58±0.53 | 0.34±0.03 | 20.41±1.70 | |

| IRS-1−/− | 29.1±2.10* | 3.58±0.31* | 0.17±0.02* | 22.62±2.77 | ||

| Muscularis | IRS-1+/+ | 14.7±0.50 | 2.02±0.10 | 0.25±0.02 | 8.18±0.48 | |

| IRS-1−/− | 9.6±0.50* | 1.16±0.10* | 0.12±0.01* | 9.87±0.96 | ||

Values are means ± SE (n = 9 littermate pairs). Sucrase activity is shown for only jejunum.

P < 0.05 for values in IRS-1−/− vs. IRS-1+/+ mice.

In the colon of IRS-1−/− mice, mucosal weight was significantly reduced to 75 ± 7% of the value in IRS-1+/+ mice and mucosal weight to 67 ± 5% (P < 0.05). There were parallel and proportionate decreases in DNA and protein (Table 2B). As in the jejunum, there were significantly lower rates of mitoses per crypt in IRS-1−/− mice (3.3 ± 0.36) compared with IRS-1+/+ mice (4.6 ± 0.32; P < 0.05). Myocyte numbers per unit area (1,000 μm2) were not significantly different in colon of IRS-1−/− mice (3 ± 0.09) vs. IRS-1+/+ littermates (3 ± 0.08; P = 0.257), indicating that the average size of enteric smooth muscle cells did not change.

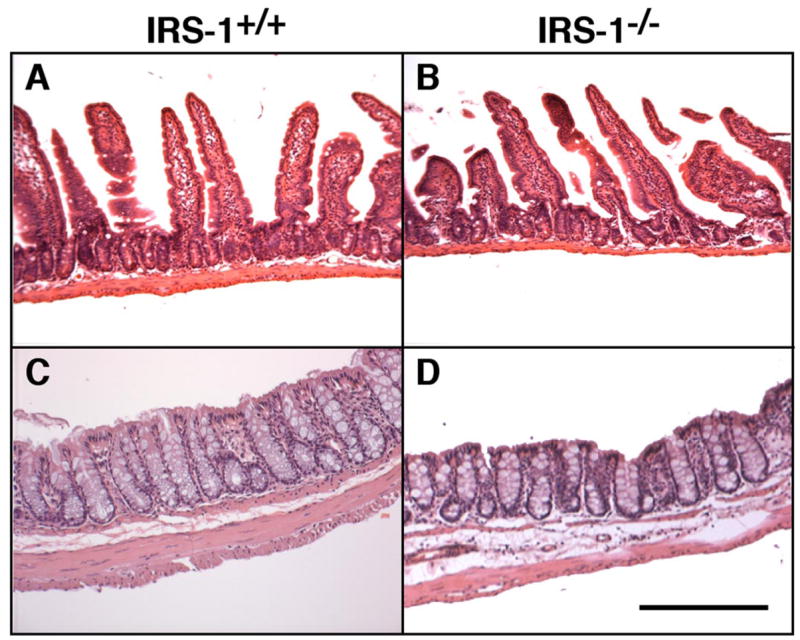

Consistent with the biochemical data, qualitative evaluation of histological sections of jejunum from IRS-1−/− and IRS-1+/+ mice revealed no major effect of IRS-1 deficiency on mucosal thickness, whereas the muscularis thickness was reduced (Fig. 1, A and B). In the colon, thickness of both mucosa and muscularis layers was decreased in IRS-1-null mice (Fig. 1, C and D).

Fig. 1.

Effects of absolute insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1 deficiency on mass of mucosa and muscularis layers in small intestine and colon. Photomicrographs of representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of jejunum and colon from IRS-1+/+ (A and C) and IRS-1−/− (B and D) mice are shown. Bar = 100 μm. Note attenuated thickness of muscularis but not of mucosal layer in IRS-1−/− jejunum and attenuated thickness of both layers in colon.

Expression of IGF-IR and associated signaling molecules in the small intestine and colon of IRS-1−/− and IRS-1+/+ mice

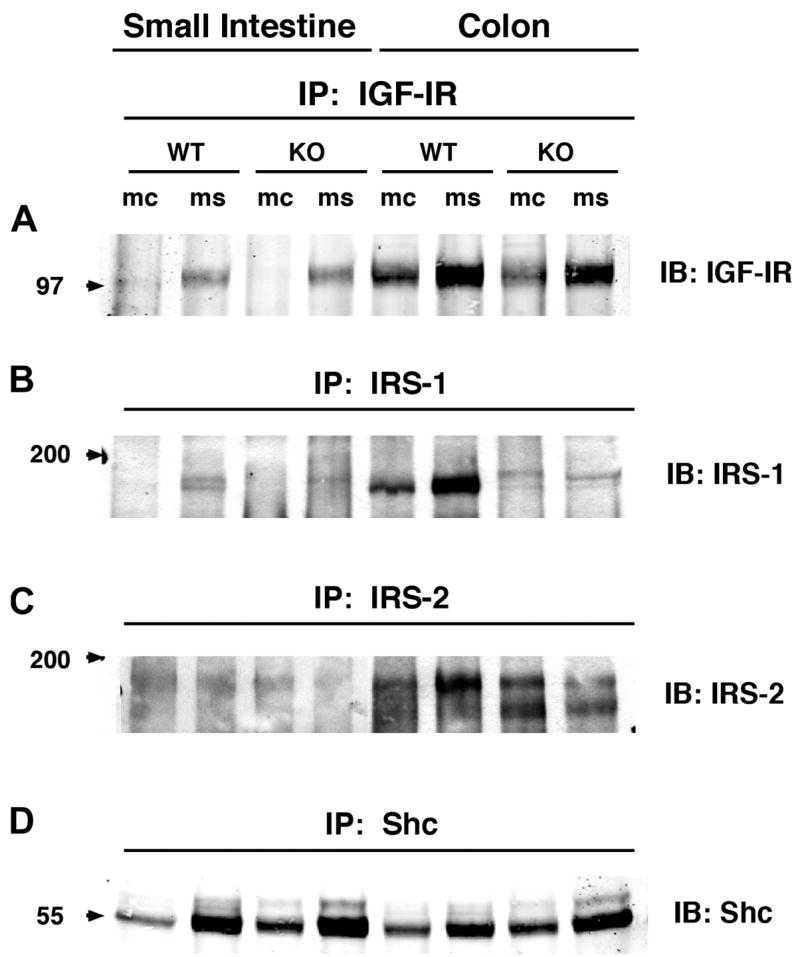

IGF-IR, IRS-1, IRS-2, and Shc were evaluated in the mucosa and muscularis of IRS-1+/+ and IRS-1−/− jejunum and colon by immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting. All of the signaling molecules were low-abundance proteins requiring immunoprecipitation of at least 8 mg of total protein extract to detect IRS-1 or IRS-2, 3 mg to detect IGF-IR, and 0.2 mg to detect Shc. Figure 2 shows representative Western immunoblots. In IRS-1+/+ and IRS-1−/− mice, IGF-IR and IRS-2 were much more readily detected in colonic mucosa and muscularis (P < 0.05; n ≥ 4 for both mediators) than in small intestine (Fig. 2). Figure 2 also shows that in WT mice, IRS-1 is detected with higher levels in colon than small intestine (P < 0.05; n ≥ 4), whereas little or no IRS-1 is detectable in small intestine or colon of IRS-1−/− mice.

Fig. 2.

Expression levels of total insulin-like growth factor-I receptor 1 (IGF-IR), IRS-1, IRS-2, and Src homology 2 domain and collagen protein (Shc) in small intestine and colon of IRS-1+/+ (WT) and IRS-1−/− (KO) mice. Protein extracts from mucosa (mc) and muscularis (ms) of small intestine and colon were immunoprecipitated (IP) with antibodies specific for IGF-IR, IRS-1, IRS-2, and Shc, as described in EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and were immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. Note faint, more slowly migrating band in IRS-1−/− extracts has been observed in analyses of other tissues from IRS-1−/− mice and probably reflects cross-reactivity of IRS-1 proteins with IRS-2 (1). Figure is representative of 4 or more independent experiments. Numbered arrows at left indicate locations of molecular-weight markers electrophoresed on same gel.

To assess whether IRS-1 deficiency caused compensatory changes in the levels of IGF-IR or IRS-2 and Shc, the major alternative signaling molecules to IRS-1, levels of expression of each intermediate in mucosa or muscularis of IRS-1+/+ mice were expressed as a ratio of the levels in corresponding samples from IRS-1+/+ littermates analyzed on the same blots. Mean values across replicate samples are shown in Table 3. IRS-1 deficiency did not significantly affect the levels of IGF-IR or IRS-2 in small intestine or colon (Table 3). In colon, there were small but significant increases in Shc expression in both mucosa and muscularis of IRS-1−/− vs. IRS-1+/+ mice, and there was a similar but nonsignificant trend toward increased Shc in small intestine of IRS-1−/− mice (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean levels of IGF-IR, IRS-2, and Shc in small intestine or colon mucosa and muscularis of IRS-1−/− mice expressed as a ratio of values in IRS-1+/+ littermates

| Mucosa | Muscularis | |

|---|---|---|

| Small Intestine | ||

| IGF-IR | 0.9±0.08 | 0.7±0.12 |

| IRS-2 | 0.5±0.14 | 0.5±0.10 |

| Shc | 1.4±0.26 | 1.4±0.20 |

| Colon | ||

| IGF-IR | 1.3±0.28 | 1.4±0.40 |

| IRS-2 | 1.1±0.19 | 1.1±0.35 |

| Shc | 1.4±0.09* | 1.8±0.26* |

Data are means ± SE; n ≥ 4 independent analyses on extracts prepared from different littermate pairs. Signal intensities for each mediator in IRS-1−/− extracts were expressed as ratio of values in corresponding mucosal or muscularis extract of IRS-1+/+ littermate evaluated in same immunoprecipitation/immunoblot experiment. IGF-IR, insulin-like growth factor-I receptor; Shc, Src homology 2 domain and collagen protein. Wilcoxon signed rank tested whether ratios differed from 1;

P < 0.05.

The higher levels of expression of IGF-IR and major IGF-IR signaling substrates in colon than those found in small intestine and the effects of IRS-1 deficiency on growth of both mucosal and muscularis layers of the colon prompted us to focus subsequent analyses on the colon.

Absolute IRS-1 deficiency impairs MT-hIGF-I-dependent growth of colonic mucosa but not muscularis

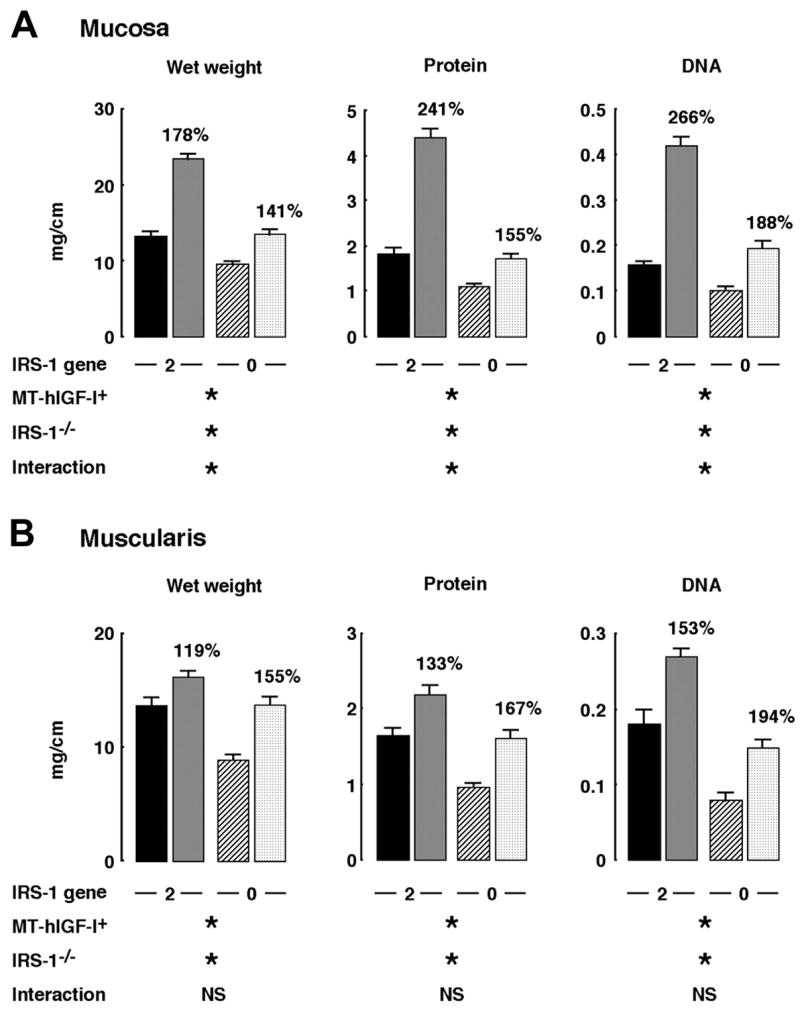

Mass of colonic mucosa and muscularis was assayed in MT-hIGF-I transgenic and WT mice with two or zero functional IRS-1 alleles to specifically test whether IRS-1 is required for trophic actions of IGF-I on the intestine in vivo. Overexpression of the MT-hIGF-I transgene increased mucosal wet weight (P < 0.001), protein content (P < 0.001), and DNA content (P < 0.001) in the colon of both IRS-1+/+ and IRS-1−/− mice, indicating that IRS-1 is not absolutely required for IGF-I-stimulated mucosal growth (Fig. 3). However, the magnitude of MT-hIGF-I-dependent mucosal growth was significantly lower in IRS-1−/− mice than in IRS-1+/+ mice (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the absence of IRS-1 impaired the growth-promoting effects of IGF-I on colonic mucosa. Two-way ANOVA confirmed significant interactions between the IGF-I transgene and IRS-1 deficiency on mucosal growth (interaction: P < 0.001 for wet weight, protein content, and DNA content). Thus these results indicate that, in vivo, MT-hIGF-I-induced overgrowth of colonic mucosa is partially dependent on IRS-1.

Fig. 3.

Effects of absolute IRS-1 deficiency on mass of colonic mucosa and muscularis in wild-type (WT) mice and mice that overexpress a human IGF-I transgene driven by a mouse metallothionein-1 promoter (MT-hIGF-I trans-genic mice). Histograms show means ± SE for wet weight, DNA, and protein content per centimeter of colonic mucosa (A) or colonic muscularis (B). Muscularis mass in colon in IRS-1+/+/WT (closed bar), IRS-1+/+/MT-hIGF-I (gray bar), IRS-1−/−/WT (hatched bar), or IRS-1−/−/MT-hIGF-I mice (cross-hatched bar) is shown. Numbers above histograms are mean values in MT-hIGF-I transgenics expressed as a percentage of values in WT mice of same IRS-1 genotype to indicate magnitude of MT-hIGF-I-dependent bowel growth. Results of 2-way ANOVA analyses on absolute values are shown, where *P < 0.001 and not significant (NS) = P > 0.05. ANOVA analyses are described in more detail in supplemental material, available on American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology website.

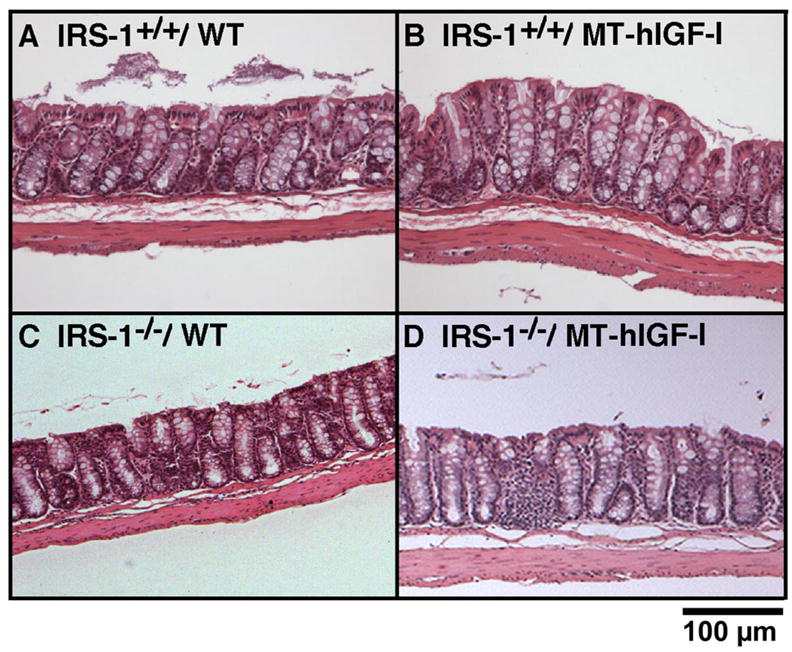

As illustrated in Fig. 3B, wet weight, protein content, and DNA content in the colonic muscularis layer of IRS-1+/+/MT-hIGF-I mice were significantly increased compared with values in IRS-1+/+/WT mice. Absolute IRS-1 deficiency did not abolish the IGF-I-induced muscularis growth (Fig. 3B). Indeed, lack of IRS-1 did not even attenuate MT-hIGF-I transgene-induced overgrowth of the muscularis (Fig. 3B; interaction: wet weight, P = 0.06; protein content, P = 0.362; DNA content, P = 0.691). These results were not due to lack of effects of IRS-1 deficiency on muscularis because two-way ANOVA revealed significant, main effects of IRS-1 deficiency to reduce all measures of muscularis mass (P < 0.001). Therefore, although IRS-1 deficiency reduces the mass of colonic muscularis, the overgrowth of the muscularis induced by MT-hIGF-I transgene overexpression in vivo does not require IRS-1 and is not attenuated by IRS-1 deficiency. Histology in Fig. 4 shows representative examples of colon from IRS-1+/+/WT, IRS-1+/+/MT-hIGF-I, IRS-1−/−/WT, and IRS-1−/−/MT-hIGF-I, which are consistent with biochemical findings.

Fig. 4.

Effects of IGF-I transgenes on mass of mucosa and muscularis in colon of WT and IRS-1-deficient mice. Photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of colon from IRS-1+/+/WT (A), IRS-1+/+/MT-hIGF-I (B), IRS-1−/−/WT (C), and IRS-1−/−/MT-hIGF-I (D) mice are shown.

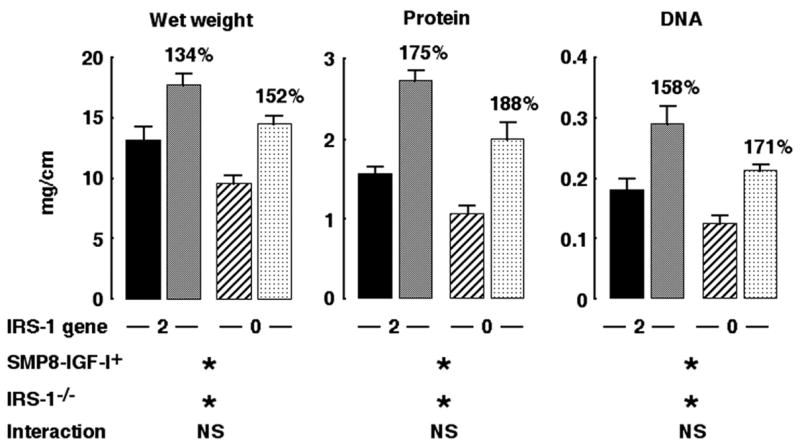

Absolute IRS-1 deficiency does not impair SMP8-IGF-I-dependent muscularis growth

To confirm that muscularis overgrowth induced by IGF-I overexpression did not depend on IRS-1, we analyzed muscularis growth in WT or SMP8-IGF-I transgenic mice with two or zero copies of IRS-1. Consistent with our previous observations (28), SMP8-IGF-I transgenic mice with two functional IRS-1 alleles showed major increases in wet weight, protein content, and DNA content of colonic muscularis compared with WT (IRS-1+/+ mice) (Fig. 5). IRS-1 deficiency had no significant impact on the magnitude of SMP8-IGF-I transgene-induced growth of colonic muscularis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effects of absolute IRS-1 deficiency on muscularis overgrowth induced by SMP8-IGF-I transgene. Muscularis mass in colon in IRS-1+/+/WT (closed bar), IRS-1+/+/SMP8-IGF-I (gray bar), IRS-1−/−/WT (hatched bar), or IRS-1−/−/SMP8-IGF-I (cross-hatched bar) mice. Histograms show absolute values for wet weight, DNA, and protein content per centimeter expressed as means ± SE; n = 12. Numbers above histograms show mean values in SMP8-IGF-I mice expressed as a percentage of values in WT mice of same IRS-1 genotype. Results of 2-way ANOVA are shown, where *P < 0.001 and NS = P > 0.05. Two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of SMP8-IGF-I transgene and significant main effects of absolute IRS-1 deficiency but no significant interaction. ANOVA analyses are described in more detail in supplemental material, available on American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology website.

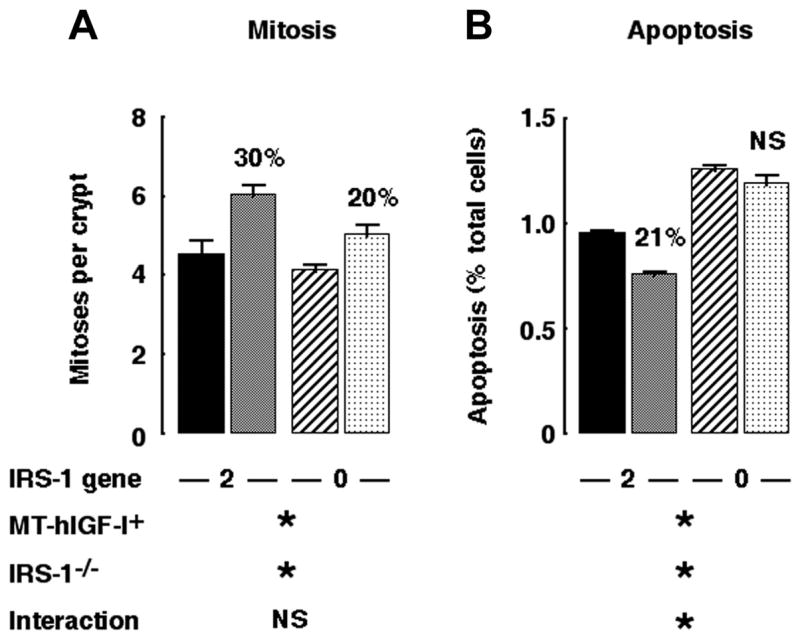

IRS-1 deficiency attenuates the antiapoptotic, but not mitogenic, actions of IGF-I in colonic mucosa

As found previously for small intestine (27), MT-hIGF transgene expression significantly increased crypt mitoses in colon of mice with two intact copies of the IRS-1 gene (Fig. 6). Crypt mitoses were also significantly increased in colon of IRS-1-deficient MT-hIGF-I transgenics. The increase was modestly attenuated compared with IRS-1+/+/MT-hIGF-I mice, but two-way ANOVA revealed no significant interaction between transgene and IRS-1 gene deletion (P = 0.369). We therefore tested whether IRS-1 deficiency impaired the antiapoptotic effects of IGF-I on colonic mucosa. As found previously in small intestine, MT-hIGF-I transgene decreased apoptosis in colon of IRS-1+/+ mice (P < 0.0001), but this effect was abolished in mice homozygous for IRS-1 gene disruption (Fig. 6). Two-way ANOVA confirmed a significant interaction (P < 0.01) between IGF-I transgene and IRS-1 deficiency on spontaneous apoptosis in colon.

Fig. 6.

IRS-1 is required for antiapoptotic but not proliferative effects of transgene-derived IGF-I. Histograms show levels of spontaneous mitoses (A) and apoptosis (B) in colonic mucosa of IRS-1+/+/WT (closed bar), IRS-1+/+/MT-hIGF-I (gray bar), IRS-1−/−/WT (hatched bar), and IRS-1−/−/MT-hIGF-I mice (cross-hatched bar). Numbers above histograms show magnitude of significant changes observed in MT-hIGF-I transgenics relative to WT mice of same IRS-1 genotype. Note that IRS-1+/+/MT-hIGF-I mice showed reduced apoptosis compared with IRS-1+/+/WT but that apoptosis in IRS-1−/−/MT-hIGF-I mice did not differ significantly from IRS-1−/−/WT mice. Results of 2-way ANOVA are shown below histograms, where *P < 0.05 for main effect of MT-hIGF-1 transgene, IRS-1 gene deletion, or interaction between transgene and IRS-1 deletion. NS = P > 0.05; n = 100 crypts assayed in at least 4 mice of each genotype.

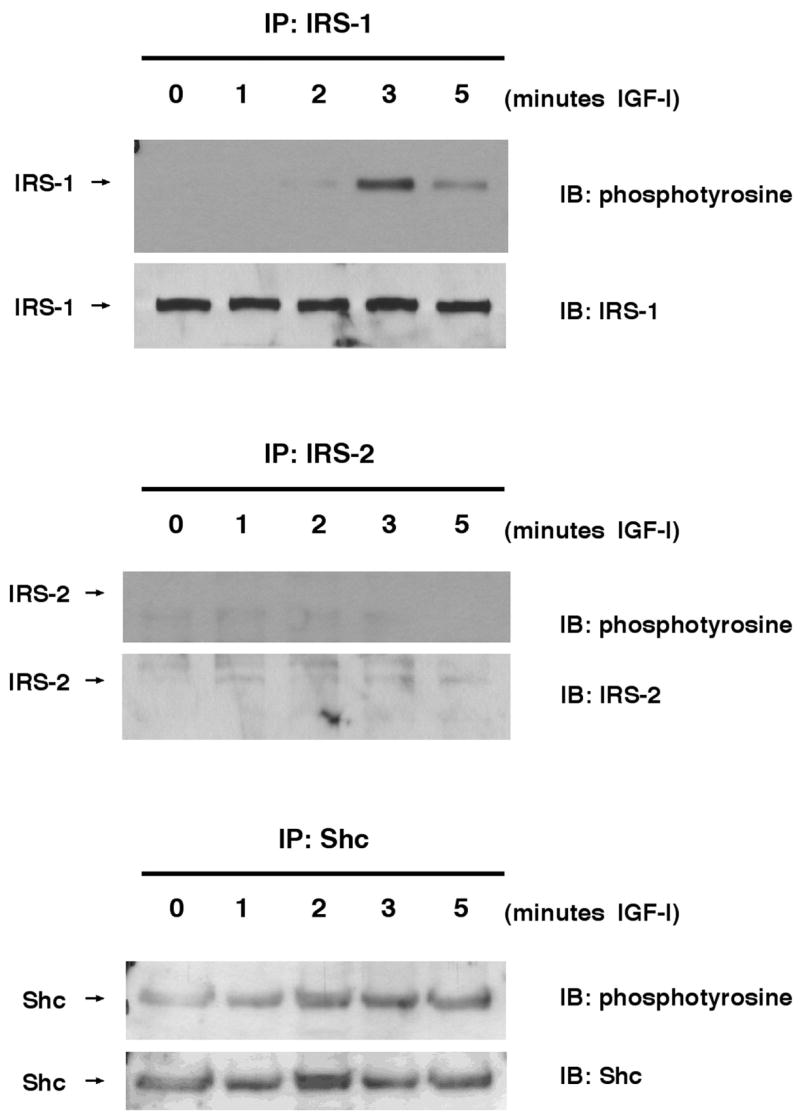

Analyses of IGF-IR signaling in cultured intestinal epithelial cells and mesenchymal cells

We tested early signaling intermediates activated by IGF-I in cultured epithelial and mesenchymal cells derived from the intestine to investigate the possible mechanisms for differential dependence on IRS-1 in the mucosa and muscularis. Nontransformed IEC-6 cells were used as a model for the intestinal epithelium because quantitative studies of IRS-1 or IRS-2 in mucosal extracts or isolated crypts proved impractical due to their low abundance and the large amounts of protein required for analyses. In IEC-6 cells, immunoblots revealed high-level expression of IRS-1, whereas IRS-2 was barely detectable (Fig. 7). IGF-I induced robust tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1, with maximum phosphorylation of IRS-1 at 3 min after stimulation, whereas no tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-2 was detected at the same (Fig. 7) or later times (unpublished data). Shc was activated by IGF-I in IEC-6 cells (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Expression and phosphorylation of IRS-1 and IRS-2 in IEC-6 rat intestinal epithelial cells. IEC-6 were serum-starved for 24 h and were treated with IGF-I (100 ng/ml) for indicated times. Cells were lysed and then immunoprecipitated with IRS-1, IRS-2, or Shc antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were electrophoresed and then immunoblotted (IB) with indicated antibodies. Immunoblots are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

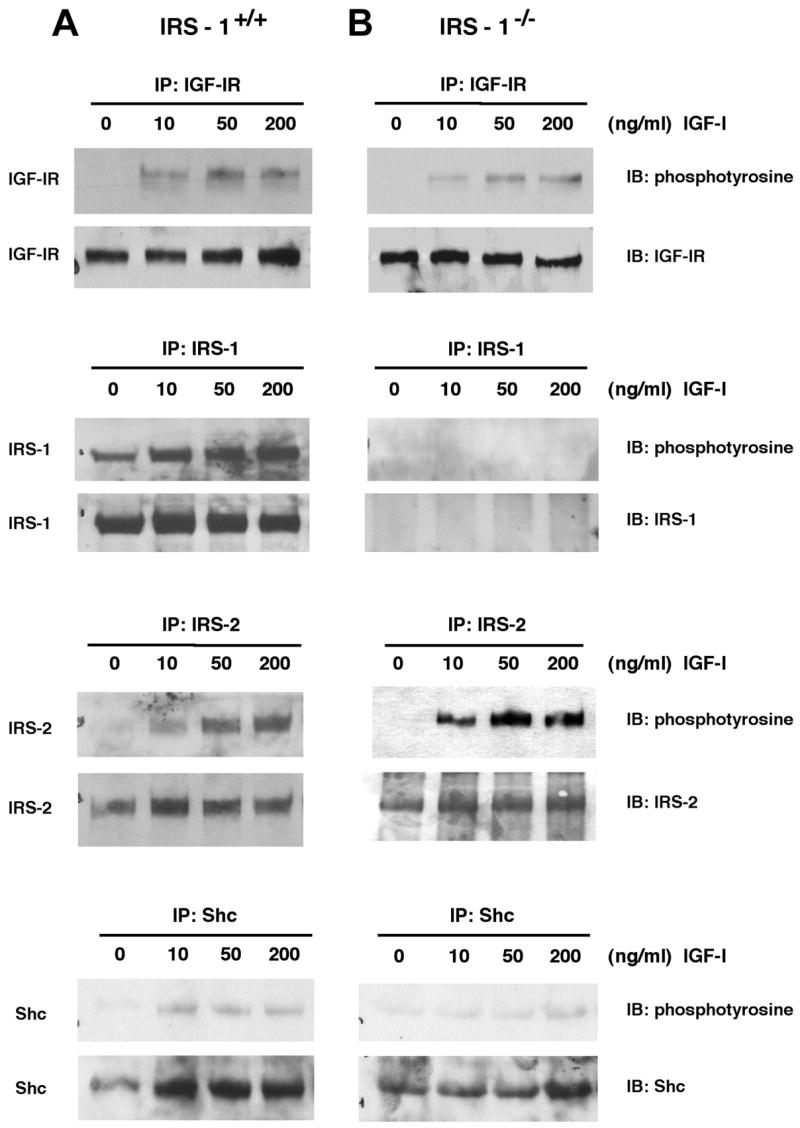

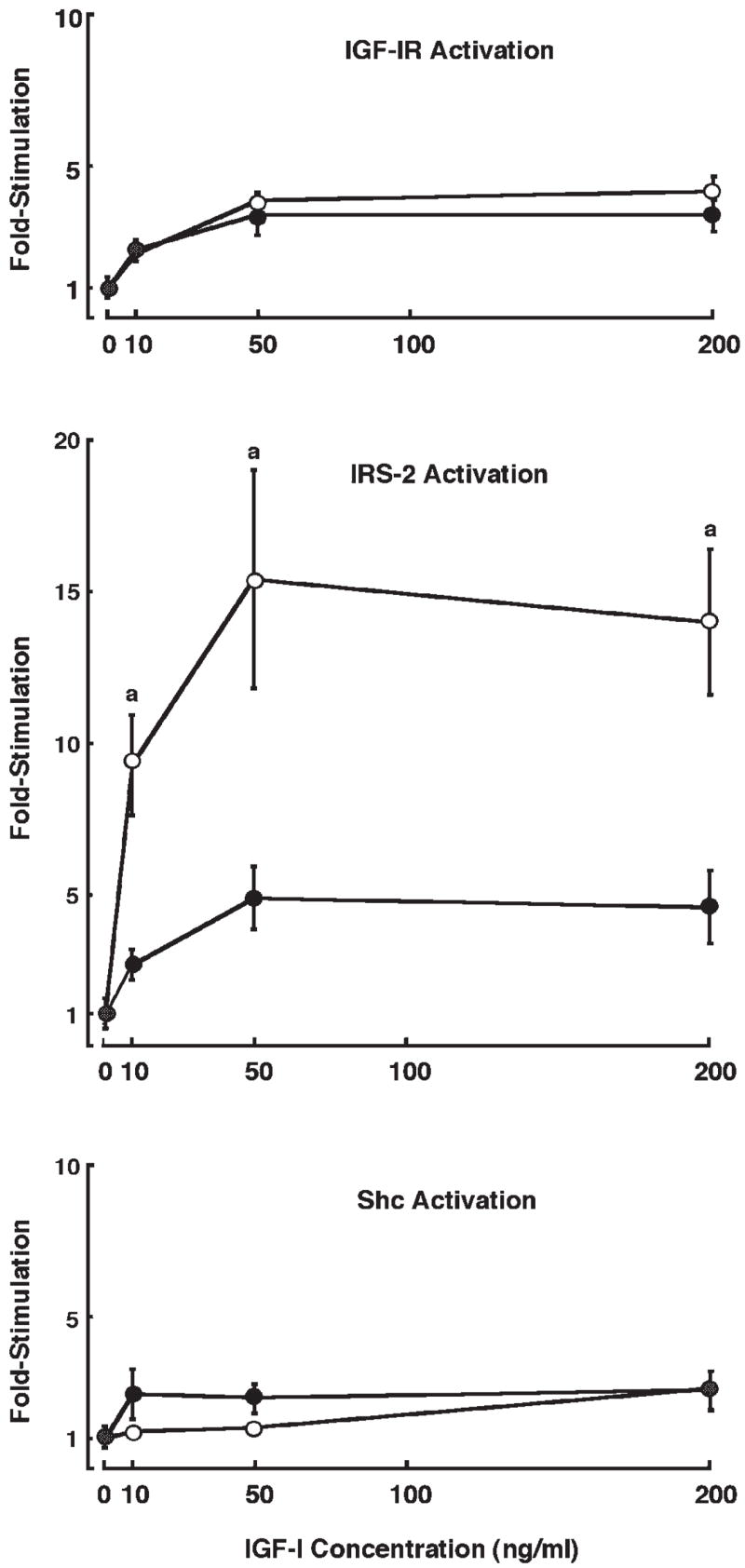

Dose-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of IGF-IR, IRS-1, IRS-2, and Shc was also examined in primary cultures of intestinal myofibroblasts from IRS-1+/+ and IRS-1−/− mice at 3 min after IGF-I stimulation, when IGF-I induces maximal IRS phosphorylation in these cells (unpublished results). Representative immunoblots are shown in Fig. 8, and quantitative data are presented in Fig. 9. IRS-1+/+ myofibroblasts show robust tyrosine phosphorylation of IGF-IR, IRS-1, IRS-2, and Shc following IGF-I stimulation. In IRS-1−/− myofibroblasts, there was no expression or tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1, but IGF-IR, IRS-2, and Shc were all activated by IGF-I (Fig. 8). IRS-1+/+ and IRS-1−/− myofibroblasts did not differ in the IGF-I-induced activation of IGF-IR (P > 0.05 at all doses; Fig. 9) or Shc (P > 0.05 at all doses; Fig. 9). Activation of IRS-2 by IGF-I was dramatically increased in IRS-1−/− myofibroblasts compared with IRS-1+/+ cells (P < 0.001 at the 50- and 200-ng doses of IGF-I; maximum IRS-2 activation in IRS-1+/+ cells was 4.9 ± 1.0-fold at the 50-ng dose of IGF-I, whereas maximum activation of IRS-2 in IRS-1−/− myofibroblasts was 15.4 ± 3.9-fold; Fig. 9). This provides evidence for compensatory increases in the ability of IGF-I to activate the alternate signaling molecule IRS-2, but not Shc, in IRS-1-deficient intestinal mesenchymal cells.

Fig. 8.

Expression and phosphorylation of IGF-IR signaling molecules in cultured intestinal mesenchymal cells. Intestinal myofibroblasts were derived from IRS-1+/+ and IRS-1−/− mice as described in EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES Cells were serum starved for 24 h and were treated with IGF-I at different doses. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against IRS-1, IRS-2, IGF-IR, or Shc and were immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. Immunoblots are representative of at least 4 separate experiments.

Fig. 9.

Magnitude of IGF-I-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of IGF-IR, IRS-2, and Shc in IRS-1+/+ (●) and IRS-1−/− (○) myofibroblasts. Intestinal myofibroblasts from IRS-1+/+ and IRS-1−/− mice were serum starved and were treated with IGF-I at different doses. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against IGF-IR, IRS-2, or Shc and were immunoblotted with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies or antibodies to total protein. Data points represent fold increases in tyrosine-phosphorylated protein vs. zero dose of IGF-I. Each data point represents a mean ± SE; n ≥ 4 independent experiments. aP < 0.05 in IRS-1−/− cells vs. IRS-1+/+ cells.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that absolute IRS-1 deficiency significantly impairs growth of both mucosa and muscularis layers in jejunum and colon. This finding extends the evidence that IRS-1 plays a key role in mediating normal intestinal growth in vivo (1, 16). Absolute IRS-1 deficiency led to reduced crypt-cell mitoses in both jejunum and colon. This impaired crypt-cell proliferation is consistent with in vitro findings that chicken hepatoma cells and embryonic fibroblasts require IRS-1 for normal cell proliferation (4, 20). Interestingly, mass of small intestinal and colonic mucosa showed a differential dependence on IRS-1. Only DNA content, but not protein content, was significantly reduced in jejunal mucosa of IRS-1−/− mice, whereas colonic mucosa showed dramatic decreases in both DNA and protein. These results indicate that jejunal mucosa may compensate more effectively than colonic mucosa for the impaired cell proliferation resulting from absolute IRS-1 deficiency by increasing the amount of protein synthesized per cell and/or cell size so that there is no discernible effect on overall mucosal mass, despite reduced cell proliferation. It seems plausible that either humoral or local factors, which act independently of IRS-1, or direct or indirect effects of nutrients may serve to maintain protein levels in jejunal mucosa during IRS-1 deficiency. Consistent with this concept, growth of jejunal mucosa is much more responsive to nutrient levels than colon (29), and recent reports demonstrate that high calorie intake or enteral nutrient combined with trophic hormones act to increase mucosal protein more than DNA content (12, 14). In addition, our results indicate that in the jejunal mucosa of both IRS-1+/+ and IRS-1−/− mice, Shc is expressed at higher levels than IRS proteins, suggesting that it may be a predominant mediator of mucosal growth in this segment. Normal levels of sucrase in the intestine of IRS-1-null mice suggest a preferential requirement for IRS-1 as a mediator of crypt proliferation vs. enterocyte differentiation in vivo. This is consistent with data from 32D cells, in which IRS-1 is required for cell growth but not cell differentiation (23, 26).

Our analyses of muscularis indicate that IRS-1 is required for normal cell number in muscularis layers of the intestine in vivo. This is consistent with findings in skeletal muscle cells that normal or IGF-I-dependent growth of gastrocnemius muscle requires IRS-1 (16). Decreased thickness of intestinal muscularis layers but no significant change in cell size in IRS-1-null mice suggests that reduced cell number is responsible for the effects of IRS-1 deficiency on muscularis growth. This likely reflects decreased enteric smooth muscle cell proliferation because a lack of IRS-1 has been found to impair proliferation of other mesenchymal cell types in vitro (4).

In intestine of IRS-1-null mice in vivo, there was no evidence for increased levels of IGF-IR or the major alternative signaling molecule, IRS-2, in the mucosa or muscularis. There appear to be tissue-specific differences in compensatory responses to IRS-1 deficiency, because in brain of IRS-1-deficient mice there is upregulation of IRS-2 levels (30). Intriguingly, specific increases in IRS-2 in the brain are also associated with minimal effects of IRS-1 deficiency on normal or IGF-I-stimulated brain growth (30). Shc expression was modestly increased in both colonic mucosa and muscularis of IRS-1-null mice, but this was not sufficient to prevent the reduced mass and growth of these layers that was observed in IRS-1-deficient mice.

We used cross-bred mice expressing IGF-I transgenes on a background of two or zero intact IRS-1 genes to specifically assess whether IRS-1 deficiency impairs the actions of IGF-1 on mucosa or muscularis in vivo. MT-hIGF-I transgene over-expression potently stimulated growth of both mucosal and muscularis layers of colon, with >200% increases in protein and DNA content in IRS-1+/+/MT-hIGF-I mice vs. IRS-1+/+/WT. These effects of the MT-hIGF-I transgene on the colonic mucosa are greater in magnitude than previously observed for small intestine (15), consistent with our current observations of higher-level expression of IGF-IR and signaling molecules in the colonic vs. jejunal mucosa. The greater IGF-I responsiveness of normal colon vs. small intestinal mucosa is relevant to the increasing evidence that elevated IGF-I is a risk factor for colorectal adenoma or cancer (7).

Our observations that IRS-1 deficiency attenuates the magnitude of IGF-I-induced overgrowth of mucosa, but not muscularis, provide novel evidence for cell type-specific dependence on IRS-1 for IGF-I-induced colon growth in vivo.

In the colon, IGF-I-induced mucosal growth was only partially dependent on IRS-1, with a 50–65% attenuation of the IGF-I-induced increases in DNA and protein in IRS-1-deficient mice. Surprisingly, this was associated with only slightly attenuated mitogenic effects of IGF-I in colonic crypts of IRS-1-null mice, whereas antiapoptotic effects of IGF-I were completely abolished by IRS-1 deficiency. Although IGF-IR/IRS-1-activated pathways have been linked to antiapoptotic actions of IGF-I in cancer cell lines derived from the intestine, there is little or no information about in vivo signal-transduction pathways required for the antiapoptotic actions of IGF-I. Our observations demonstrate that one key IGF-I signaling molecule, IRS-1, is required for protective actions of IGF-I against crypt cell apoptosis in vivo.

The fact that IRS-1 deficiency did not impair IGF-I-dependent growth of colon muscularis demonstrates that enteric smooth muscle does not require IRS-1 for IGF-I-dependent growth. It is well known that growth of intestinal smooth muscle cells in vitro can be regulated by IGF-I (10, 31) and that IGF-I stimulation recruits IRS-1 to IGF-IR (9); however, little information is available about the primary signaling molecules that are required for IGF-I-induced enteric smooth muscle cell growth in vivo. Our prior in vivo study indicated that IRS-1 is required for IGF-I-dependent growth in skeletal muscle cells (16), and studies in cultured embryonic fibroblasts indicate that normal growth of some mesenchymal cell types requires IRS-1 (4). Thus enteric smooth muscle cells differ from other mesenchymal cells in the lack of dependence on IRS-1. IRS-2 and Shc, which we found to be expressed in intestinal muscularis, could serve as alternate mediators of IGF-I action rather than IRS-1. The significant 80% increase in Shc levels observed in colon muscularis of IRS-1-null mice suggests that Shc may serve as an alternate signaling molecule for IRS-1 action in colon muscularis. We attempted to test whether tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc or IRS-2 was upregulated in colon muscularis of IRS-1−/−/MT-hIGF-1 compared with IRS-1+/+/MT-hIGF-I mice, but this proved problematic because of low-level IRS-2 expression and inability to consistently detect tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in tissue extracts. However, studies in primary mesenchymal-cell cultures demonstrate that IGF-I-dependent IRS-2 activation, but not Shc activation, was dramatically upregulated in IRS-1−/− intestinal mesenchymal cells on IGF-I stimulation. Intestinal mesenchymal cells differ from IRS-1−/− embryonic fibroblasts, which do not show upregulated activation of alternative signaling molecules (4), further pointing to cell- and tissue-specific differences in IGF-I signaling pathways.

The lack of dependence on IRS-1 for IGF-I-induced muscularis growth in vivo appears paradoxical given the reduced mass of enteric smooth muscle layers in IRS-1−/− mice relative to IRS-1+/+ mice. This suggests that normal growth of intestinal muscularis is regulated by other IRS-1-linked hormones than IGF-I, which could include growth hormone and angiotensin II, which both have trophic effects on smooth muscle and both activate IRS-1 (6, 17).

Normal MT-hIGF-1-mediated muscularis overgrowth in IRS-1−/− mice could reflect some compensatory responses to long-term elevations of circulating IGF-I that occur in these transgenics. We therefore used a second model, SMP8-IGF-I/WT and SMP8-IGF-I/IRS-1−/− mice, to directly assess the requirement of the intestine for IRS-1 in mediating autocrine/paracrine actions of IGF-I expressed specifically in the intestinal muscularis layers. Our results in these mice provide independent confirmation that IRS-1 is not required for IGF-I-mediated growth of the muscularis. SMP8-IGF-I transgenics show no increase in plasma levels of IGF-I (25, 28) and, therefore, results in these mice are not confounded by secondary effects that could occur due to long-term effects of elevated circulating IGF-I.

We can only speculate on the biological reason why the colonic epithelium should have greater dependence on IRS-1 for growth-promoting and antiapoptotic actions of IGF-I compared with muscularis. Low apoptosis within colonic crypts is linked to increased risk the development of precancerous adenomatous lesions within the colonic epithelium (8), and much evidence suggests a role of IGF-I in colon cancer risk (7). The dependence of the epithelium but not muscularis on IRS-1 may therefore serve as a protective mechanism against protumorigenic effects of IRS-1.

In conclusion, our findings provide new in vivo evidence for cell type-specific requirements for IRS-1 as a mediator of normal or IGF-I-induced intestinal growth that could not have been predicted from in vitro findings or observations in other tissues. Specifically, 1) normal crypt cell mitoses in colonic and jejunal mucosa require IRS-1; 2) in jejunal mucosa, normal DNA but not protein or sucrase activity in the mucosa requires IRS-1, whereas in colon, DNA and protein content are both affected by IRS-1 deficiency; 3) using a cross-breeding approach to generate mice that overexpress IGF-I on a background of normal or zero levels of IRS-1, we demonstrated that mucosa, but not muscularis, shows partial dependence on IRS-1 for IGF-I-induced growth in vivo; 4) the mucosal growth deficit in IRS-1−/−/MT-hIGF-I mice involves impaired ability of IGF-I to reduce apoptosis rather than impaired mitogenic actions; 5) in vitro findings indicate that IRS-1 is used in preference to IRS-2 to mediate IGF-I action in intestinal epithelial cells, whereas intestinal mesenchymal cells use both IRS-1 and IRS-2 to mediate IGF-I action; and 6) activation of IRS-2 is upregulated in IRS-1-deficient intestinal mesenchymal cells.

Acknowledgments

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-40247 (P. K. Lund) and CA-44684-12 (J. G. Simmons). H. R. Wilkins is a fellow in the Seeding Postdoctoral Innovators in Research and Education (SPIRE) program. Histology and Imaging Cores of the Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease (DL-34987) and Lineberger Cancer Center facilitated this work.

References

- 1.Araki E, Lipes MA, Patti ME, Bruning JC, Haag B, 3rd, Johnson RS, Kahn CR. Alternative pathway of insulin signalling in mice with targeted disruption of the IRS-1 gene. Nature. 1994;372:186–190. doi: 10.1038/372186a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baserga R. The contradictions of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Oncogene. 2000;19:5574–5581. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blakesley V, Butler A, Koval A, Okubo Y, LeRoith D. IGF-1 receptor function: transducing the IGF-1 signal into intracellular events. In: Rosenfeld R, Roberts CT, editors. Contemporary Endocrinology: The IGF System. Totowa, NJ: Humana; 1999. pp. 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruning JC, Winnay J, Cheatham B, Kahn CR. Differential signaling by insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and IRS-2 in IRS-1-deficient cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1513–1521. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bustin SA, Jenkins PJ. The growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor-I axis and colorectal cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:447–454. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukuda N, Satoh C, Hu WY, Nakayama M, Kishioka H, Kanmatsuse K. Endogenous angiotensin II suppresses insulin signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells from spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1651–1658. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200109000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giovannucci E. Insulin, insulin-like growth factors and colon cancer: a review of the evidence. J Nutr. 2001;131:3109S–3120S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.3109S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keku TOLP, Galanko J, Simmons JG, Woosley JT, Sandler RS. Insulin resistance, apoptosis, and colorectal adenoma risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2076–2081. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuemmerle JF. Occupation of αvβ3-integrin by endogenous ligands modulates IGF-I receptor activation and proliferation of human intestinal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G1194–G1202. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00345.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuemmerle JF, Bushman TL. IGF-I stimulates intestinal muscle cell growth by activating distinct PI 3-kinase and MAP kinase pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1998;275:G151–G158. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.1.G151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laburthe M, Rouyer-Fessard C, Gammeltoft S. Receptors for insulin-like growth factors I and II in rat gastrointestinal epithelium. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1988;254:G457–G462. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1988.254.3.G457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu XND, Holst JJ, Ney DM. Synergistic effect of supplemental enteral nutrients and exogenous glucagon-like peptide 2 on intestinal adaptation in a rat model of short bowel syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1142–1150. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.5.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meytes PWB, Christoffersen CT, Urs B, Gronshkow K, Latus LJ, Yakushiji F, Ilondo MM, Shymko RM. The insulin-like growth factor I receptor. Hormone Res. 1994;42:152–169. doi: 10.1159/000184188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mozes SSZ, Lenhardt L. Functional changes of the small intestine in over- and undernourished suckling rats support the development of obesity risk on a high-energy diet in later life. Physiol Res. 2007;56:183–192. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohneda K, Ulshen MH, Fuller CR, D’Ercole AJ, Lund PK. Enhanced growth of small bowel in transgenic mice expressing human insulin-like growth factor I. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:444–454. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9024298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pete G, Fuller CR, Oldham JM, Smith DR, D’Ercole AJ, Kahn CR, Lund PK. Postnatal growth responses to insulin-like growth factor I in insulin receptor substrate-1-deficient mice. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5478–5487. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson CA, Carey HV, Hinton PL, Lo HC, Ney DM. GH elevates serum IGF-I levels but does not alter mucosal atrophy in parenterally fed rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1997;272:G1100–G1108. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.5.G1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simmons JG, Pucilowska JB, Keku TO, Lund PK. IGF-I and TGF-β1 have distinct effects on phenotype and proliferation of intestinal fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G809–G818. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00057.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simmons JG, Pucilowska JB, Lund PK. Autocrine and paracrine actions of intestinal fibroblast-derived insulin-like growth factors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1999;276:G817–G827. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.4.G817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taouis M, Dupont J, Gillet A, Derouet M, Simon J. Insulin receptor substrate 1 antisense expression in an hepatoma cell line reduces cell proliferation and induces overexpression of the Src homology 2 domain and collagen protein (SHC) Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;137:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(97)00245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Termanini B, Nardi RV, Finan TM, Parikh I, Korman LY. Insulin-like growth factor I receptors in rabbit gastrointestinal tract. Characterization and autoradiographic localization. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:51–60. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulshen MH, Dowling RH, Fuller CR, Zimmermann EM, Lund PK. Enhanced growth of small bowel in transgenic mice overexpressing bovine growth hormone. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:973–980. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90263-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valentinis B, Navarro M, Zanocco-Marani T, Edmonds P, McCormick J, Morrione A, Sacchi A, Romano G, Reiss K, Baserga R. Insulin receptor substrate-1, p70S6K, and cell size in transformation and differentiation of hemopoietic cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25451–25459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Tol EA, Holt L, Li FL, Kong FM, Rippe R, Yamauchi M, Pucilowska J, Lund PK, Sartor RB. Bacterial cell wall polymers promote intestinal fibrosis by direct stimulation of myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1999;277:G245–G255. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.1.G245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Niu W, Nikiforov Y, Naito S, Chernausek S, Witte D, LeRoith D, Strauch A, Fagin JA. Targeted overexpression of IGF-I evokes distinct patterns of organ remodeling in smooth muscle cell tissue beds of transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1425–1439. doi: 10.1172/JCI119663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White MF. The insulin signalling system and the IRS proteins. Diabetologia. 1997;40:S2–S17. doi: 10.1007/s001250051387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilkins H, Ohneda K, D’Ercole AJ, Fuller CR, Williams KL, Lund PK. Reduction of spontaneous and irradiation-induced apoptosis in the small intestinal mucosa of IGF-I transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G457–G464. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00019.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams KL, Fuller CR, Fagin J, Lund PK. Mesenchymal IGF-I overexpression: paracrine effects in the intestine, distinct from endocrine actions. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G875–G885. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00089.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winesett DE, Ulshen MH, Hoyt EC, Mohapatra NK, Fuller CR, Lund PK. Regulation and localization of the insulin-like growth factor system in small bowel during altered nutrient status. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1995;268:G631–G640. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.268.4.G631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye P, Li L, Lund PK, D’Ercole AJ. Deficient expression of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) fails to block insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) stimulation of brain growth and myelination. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;136:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimmermann EM, Sartor RB, McCall RD, Pardo M, Bender D, Lund PK. Insulin-like growth factor I induces collagen and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 mRNA in rat intestinal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1997;273:G875–G882. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.4.G875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]