Abstract

Protein Kinase C (PKC) isoforms have been identified as major cellular signaling proteins that act directly in response to oxidation conditions. In retina and lens two isoforms of PKC respond to changes in oxidative stress, PKCγ and PKCε, while only PKCε is found in heart. In heart the PKCε acts on connexin 43 to protect from hypoxia. The presence of both isoforms in the lens led to this study to determine if lens PKCε had unique targets. Both lens epithelial cells in culture and whole mouse lens were examined using PKC isoform-specific enzyme activity assays, co-immunoprecipitation, confocal microscopy, immunoblots, and light and electron microscopy. PKCε was found in lens epithelium and cortex but not in the nucleus of mouse lens. The PKCε isoform was activated in both epithelium and whole lens by 5% oxygen when compared to activity at 21% oxygen. In hypoxic conditions (5% oxygen) the PKCε co-immunoprecipitated with the mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase IV subunit (CytCOx). Concomitant with this the CytCOx enzyme activity was elevated and increased co-localization of CytCOx with PCKε was observed using immunolabeling and confocal microscopy. In contrast, no hypoxia-induced activation of CytCOx was observed in lenses from the PKCε knockout mice. Lens from 6 week old PKCε knockout mice had a disorganized bow region which was filled with vacuoles indicating a possible loss of mitochondria but the size of the lens was not altered. Electron microscopy demonstrated that the nuclei of the PCKε knockout mice were abnormal in shape. Thus, PKCε is found to be activated by hypoxia and this results in the activation of the mitochondrial protein CytCOx. This could protect the lens from mitochondrial damage under the naturally hypoxic conditions observed in this tissue. Lens oxygen levels must remain low. Elevation of oxygen which occurs during vitreal detachment or liquification is associated with cataracts. We hypothesize that elevated oxygen could cause inhibition of PKCε resulting in a loss of mitochondrial protection.

Keywords: protein kinase C epsilon, lens, mitochondria, cytochrome C oxidase IV

Introduction

Protein Kinase C is part of the ABC family of serine-threonine protein kinases. Their dependence on lipids, specifically diacylglycerol (DAG), for activation is well known (Nishizuka, 1986, Parker, 2000). It is now well accepted that PKCs are primary targets of tumor promoting phorbol esters. More recently, it has become evident that some PKCs are activated by oxidative stress through their C1 domains. For example, the conventional isoform, PKCγ, is activated directly by hydrogen peroxide (Lin, et al., 2005). PKCγ is most noted for its function in neural tissue and likely acts in a neural protective role (Hayashi, 2005). Other PKCs, including PKCε, are activated by hypoxia, through unknown mechanisms (Cai, 2003). During ischemia in heart, it is known that some PKCs are translocated to cellular destinations which include the plasma membrane (Spitaler, 2004), golgi (Schultz, 2004), nucleus (Eitel, 2003), mitochondria (Li, 1999), and other cellular compartments (Zeidman, 2002). PKCs have been reported to interact with many target proteins and can form signaling complexes with many partners upon activation (Edmondson, 2002).

The conventional isoform, PKCγ, is activated during oxidative stress and translocates to plasma membrane gap junction proteins, causing inhibition of gap junction activity and subsequent protection from oxidative stress (Lin, et al., 2005). Because gap junctions are used in cell-to-cell communication pathways, PKCγout mice display learning deficits, insensitivity to pain, do not develop tolerance to alcohol like normal mice ( Abeliovich, et al., 1993), and are more sensitive to hydrogen peroxide induced cataract formation (Lin, 2006). It is thought that these deficits are partially a result of the improper control of gap junctions due to loss of PKCγ (Lin, et al., 2007).

In contrast, PKCε is known to translocate to mitochondria during hypoxia in heart where it interacts with several targets. For example, by activating K+-ATP sensitive channels and inhibiting the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), PKCε is suspected to stabilize mitochondria (Costa, 2006). PKCε knock-out mice do not develop tolerance to ischemia, and mice which express constituitively active PKCε demonstrate increased adenosine nucleotide translocase activity, decreased cytochrome c release, and stabilization of the inner mitochondrial membrane potential (McCarthy, 2005). Another target for PKCε associated with mitochondria is Bcl-2 associated death domain protein (BAD). PKCε plays an anti-apoptotic role in these instances and seems to be compensating for energy deficits and apoptotic signals encountered during hypoxia (Baines, 2002). During cardiac ischemia PKCε also associates with mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase IV (CytCOx) resulting in activation of the CytCOx (Ogbi and Johnson, 2006). PKCε is widely expressed in the heart and neural tissue, including retina and lens (Berthoud, et al., 2000).

Since the lens is naturally hypoxic, PKCε could play a vital role in protection of mitochondria from hypoxia-induced apoptosis. In this manuscript we present data to show that PKCε is widely expressed in the lens epithelium and cortical fibers. Furthermore, the PKCε was activated by hypoxia (5% O2, 12 hours) in lens epithelial cells and in whole lens in culture. Using mouse lenses or isolated lens mitochondria, co-immunoprecipitation, and confocal microscopy, PKCε was found to associate with lens mitochondrial CytCOx. Co-immunoprecipitation and activity studies from PKCε knock-out mice demonstrated that the CytCOx was activated under hypoxic conditions in control but not in PKCε knockout mouse lens mitochondria. Thus, PKCε may serve a protective role from hypoxia in the lens mitochondria through activation of CytCOx.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Kansas State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice, including control and PKCε knock-out mice, were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, MA, USA) and maintained as colonies in the Animal Research Facility at the College of Veterinary Medicine. PKCε knock-out mice were obtained from breeding heterozygous individuals and genotyping of the offspring by PCR of tail snips. The control mice are B6.129S4-Prkce/tm1/Msg/J and the PKCε heterozygous mice (+/− for PKCε) are Prcke/tm1/Msg-2-3. All mice were used at 6 weeks of age. The failure of the PKCε −/− mice to produce PKCε protein was further verified by Western blotting with PKCε antisera. Mice were sacrificed by CO2 followed by cervical dislocation. Lens tissues were used immediately. All experiments conformed to the ARVO Statement for Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Cell and Tissue Culture

N/N1003A rabbit lens epithelial cells or whole mouse lenses were cultured in low glucose DMEM cell culture media with 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 0.05 unit/ml penicillin, 50μg/ml streptomycin, pH 7.4 at 37 º C with 10% fetal calf serum, in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 for normoxic conditions, (21% oxygen). Cells in culture were made hypoxic (5% oxygen) in a O2/CO2 dual controlled chamber (BioSpherix, ProOx Model, C21, Redfield, NY, USA) inserted into a temperature controlled incubator set at 37º C. The pH was monitored by use of a pH-sensitive dye included in the cell media. For hypoxic conditions of whole lenses each lens was removed and immediately put into N2 -bubbled DMEM in the absence of O2 compared to lenses incubated in DMEM in room O2 for normoxic studies. Lens were then incubated in the chamber as described above. All subsequent procedures under hypoxia used buffers which had been depleted of oxygen by nitrogen bubbling. Lens tissues or cells were homogenized on ice in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/Cl pH 7.5, 1mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1–2% Triton-100), with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA,USA ). After homogenization with a Dounce homogenizer, lysates were sonicated on ice and used immediately for immunoprecipitation, activity studies, or SDS PAGE and subsequent immunoblotting.

Enzyme Activity Assays

The activity of PKCε was measured using a method based on immunoprecipitation and ability for the immuno-purified PKC to phosphorylate a synthetic peptide supplied with the kit. After treatment of cells in culture or lenses under normoxic or hypoxic conditions, the activated PKC is maintained in its activated state by preservation of autophosphorylation of the PKCε on Ser729, which is a direct indication of enzyme activation (Cenni, et al., 2002). This is accomplished by use of the phosphatase inhibitory cocktail which is included in all buffers and assay buffers. PKCε was immunoprecipitated from cells or lens homogenates with PKCε antibodies (catalog #06-991, Upstate Biotechnology, Charlottesville, VA, USA) directed to a C-terminal fragment of PKCε. The precipitate was reacted with protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA,USA). The activity of the immuno-purified PKCε was measured using a commercial assay kit (Stressgen,Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Briefly, immunoprecipitated PKCε was added directly to a microtiter plate that contained a synthetic peptide substrate corresponding to the PKCε consensus substrate peptide included by the supplier (P-L-S-R-T-L-S-V-A-A-K). After the reaction was stopped, an antibody specific for the phosphorylated substrate was added followed with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. The signal was visualized with tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate and detected at 450 nm in a 96-well plate reader.

General mitochondrial function was determined by measurement of cytochrome C oxidase subunit IV, a part of the cytochrome C oxidase subunit complex, and a terminal step in electron transport.

For assay of cytochrome C oxidase subunit IV (CytCOx), mitochondria were isolated from mouse lenses, placed in lysis buffer, then the ability of CytCOx to oxidize fully reduced ferrocytochrome C to ferricytochrome C was measured using spectrophotometry on a 96-well format. The mitochondrial isolation kit (#KC010100) and mitochondrial activity assay kit (#KC310100) were purchased from Biochain Institue, (Hayward, CA,USA) and the absorbance of oxidized ferricytochrome C was measured as a loss of absorbance at 550nm in a 96-well plate reader as per the instructions. For mitochondrial isolation, cells or tissues were homogenized repeatedly with a dounce tissue homogenizer on ice but were not sonicated. Mitochondria were isolated according to the directions and stored in mitochondrial storage buffer at − 80°C. Mitochondrial preparations were verified by assaying CytCOx in the presence and absence of n-Dodecyl β-D-Maltoside. For mitochondrial protein lysate, the mitochondrial preparations were pelleted and dissolved in lysis buffer. Mitochondrial isolation buffer, storage buffer, and lysis buffer were from Biochain Institute and were bubbled with nitrogen for hypoxia studies.

The significance of the measurements for control and experimental groups was determined with Origin software (Microcal Software Inc., Northampton, MA). In all cases at least 5 measurements were taken. p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for PKC and CytCOx enzyme activity.

Sectioning and Light and Confocal Microscopy

Mouse eyes were removed and kept on ice and immediately fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M Na-cacodylate, pH 7.3 at 4 °C. After fixation for 24–48 hours, lenses were post-fixed with osmium tetroxide, dehydrated, and embedded in Epon (LX112). Sections (1μm thick) were stained with Toluidine Blue and viewed under a Nikon microscope at 20X or 40X. For confocal microscopy, N/N1003A cells were grown on 12-well plates to 70% confluency and treated for 12 hr. in 5% (hypoxic) or 21% (normoxic) oxygen. Cells were then fixed in 2.5% paraformaldehyde for 5 min., blocked with 3% BSA in PBS for 1 hr. at room temperature, then labeled with antiPKCε and/or anti-CytCOxIV antisera for 2 hr. at room temperature. After rinsing in PBS, cells were incubated in secondary anti-sera, Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H&L) or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H&L) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The cells were then mounted and viewed using a Nikon C1 confocal microscope and results are samples of 3 experiments with 12 pictures taken from random areas of each sample.

Co-immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

For co-immunoprecipitation, lysates were incubated overnight with the appropriate antibodies at 4 °C. The complexes were captured on protein A/G agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 30 minutes and then isolated by centrifugation. The isolated complexes were denatured with SDS loading buffer and the samples were separated by PAGE as previously described (Lin, et al., 2005). After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blots were blocked in 5% w/v milk or blocking buffer (Zymed, San Francisco, CA,USA) and incubated with appropriate antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The blots were visualized with chemiluminesence (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Monoclonal antibodies against CytCOx IV were purchased from MitoSciences (Eugene,OR,USA, cat# MS407).

Results

Lens PKC ε is activated by hypoxia

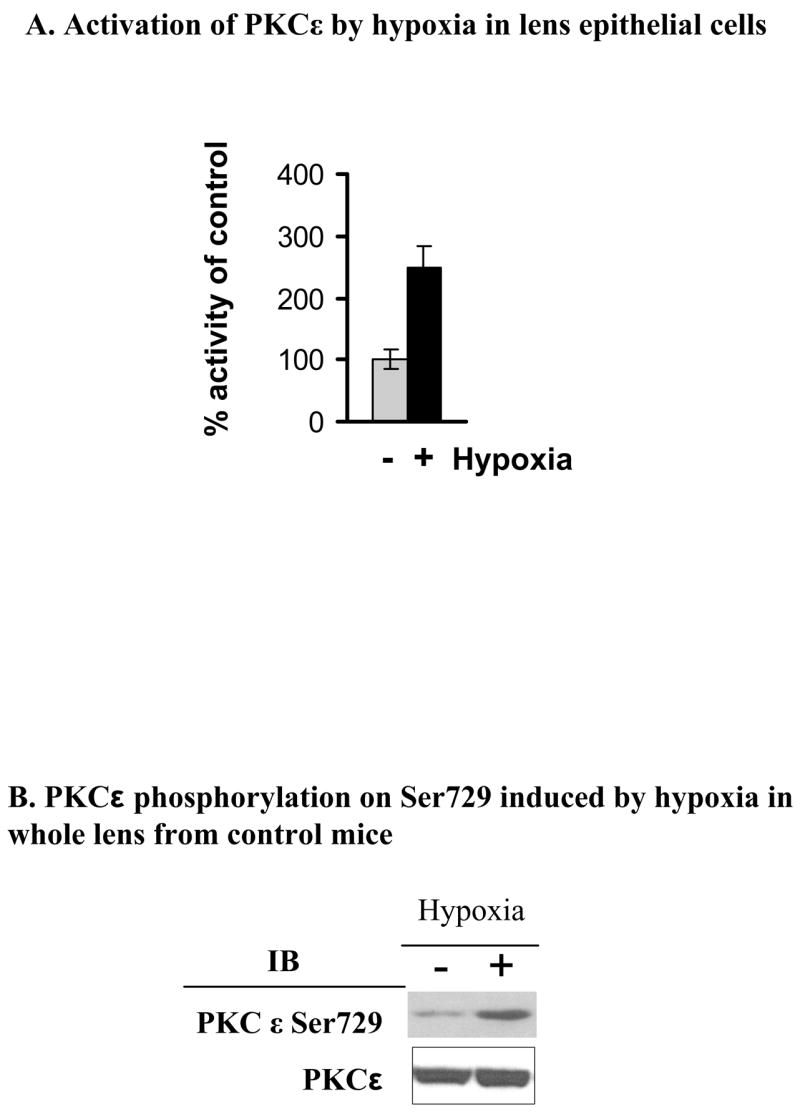

Previous reports demonstrate that PKC ε is widely expressed in lens but that activators of the conventional PKCγ, for example TPA, do not have any effect on the activity of PKCε (Berthoud, et al., 2000). In contrast, several reports demonstrate that in heart tissue, PKCε is activated by both TPA and hypoxic conditions, and that upon activation, this isoform translocates to distinct cellular locations such as to mitochondria (Ogbi and Johnson, 2006). To determine if PKCε is activated by hypoxia in lens epithelial cells, N/N1003A cells were incubated in either normoxic (21% oxygen) or hypoxic (5% oxygen) conditions for 12 hr. The results demonstrate that PKCε was activated to 2.5 times that of the normoxic PKCε (set as 100%) in lens epithelial cells in culture (Fig. 1 A). It is difficult to maintain lenses under hypoxia during the immunoprecipitations and assays shown in Fig. 1A. Therefore, auto-phosphorylation of PKCε on Ser729 was used as an indication of enzyme activation in whole lens (Cenni, et al, 2002). This can be assessed by immediately homogenizing the whole lens after normoxic or hypoxic incubation in SDS sample buffer. As shown in Fig. 1B, using specific pSer729 antisera, the PKCε from hypoxic-treated lenses had increased phosphorylation of Ser729 of PKCε. This further suggests that PKCε is activated by hypoxia in both lens epithelial cells in culture and in whole mouse lenses.

Figure 1. Hypoxia-induced PKCε activation in the lens.

A. Enzyme activity of PKCε in N/N1003A rabbit lens epithelial cells was determined as described in the Methods Section. In the wild type lens epithelial cells (N/N1003A) treated with hypoxia (5% O2) or normoxic (21 % O2) for 12 hours, PKCε was activated about 2.5 fold over control (set at 100%). Equal PKCε per lane was verified using PKCε antisera and western blots. B. The whole lenses from control mice were made hypoxic as described. PKCε phosphorylation on Ser729 was determined by Western blotting using anti-phospho-PKCε Ser729 antisera. Total PKCε is a loading control.

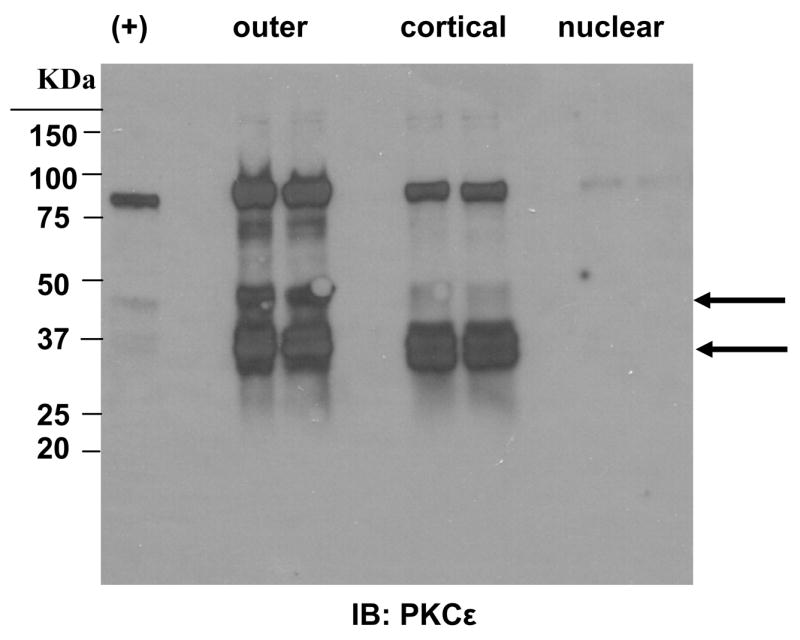

PKCε is widely expressed in lens

In order to determine where PKCε is expressed and maintained in whole mouse lens, lenses from 6 week old control mice were dissected into the outer region (Outer, Fig. 2), (approximately into the bow region), the cortical region (the remainder of the lens minus the nucleus, cortical, in Fig. 2), and the nuclear region (nuclear in Fig. 2). Western blots shown in Fig. 2 demonstrate the presence of PKCε in both the outer and cortical regions but not in the nucleus. The antisera are C-terminally directed and, thus, the lower bands (see arrows) recognize the cleaved catalytic subunit of the PKCε which is reported to be constitutively activated (Baxter, et al., 1992). This antisera shows no reactivity in these regions using lens from the PKCε knockout mice, demonstrating specificity of this antisera (Fig. 4). Cleavage of PKCε occurs upon persistent activation of this enzyme, suggesting that the natural hypoxia of the lens may produce a sustained activation of PKCε in lens.

Figure 2. PKCε is widely expressed in the lens epithelium and cortex.

Lenses of control mice were dissected as described. Tissue homogenates were subjected to Western blotting to detect PKCε expression. += PKCε positive control included with antisera. Lanes are duplicates. Arrows indicate the catalytic fragments of PKCε.

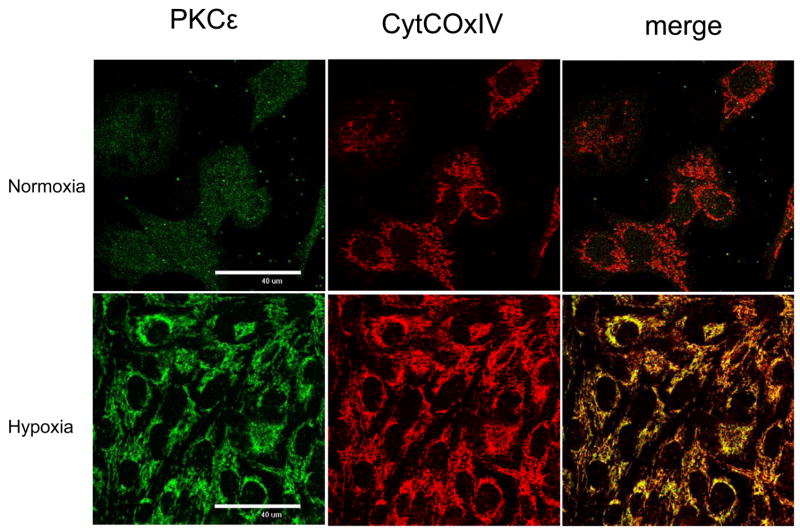

Figure 4. Co-localization of PKCε with CytCoxIV after hypoxia.

N/N cells were seeded in 12 well plates to 70% confluence before hypoxia treatment at 5% O2 for 12 hr. Cells were fixed with 2.5% paraformaldehyde for 5 min., blocked with 3% BSA in PBS for 1 hr at room temperature, and then labeled with anti-PKCε (Abcom, Cambridge MA) or CytCOxIV (MitoSciences, Eugene, OR) for 2 hr at room temperature. After washing, the cells were incubated with the secondary antisera Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Molecular Probes, Oregon). The cells were then mounted on slides and examined using a Nikon C1 scanning confocal microscope.

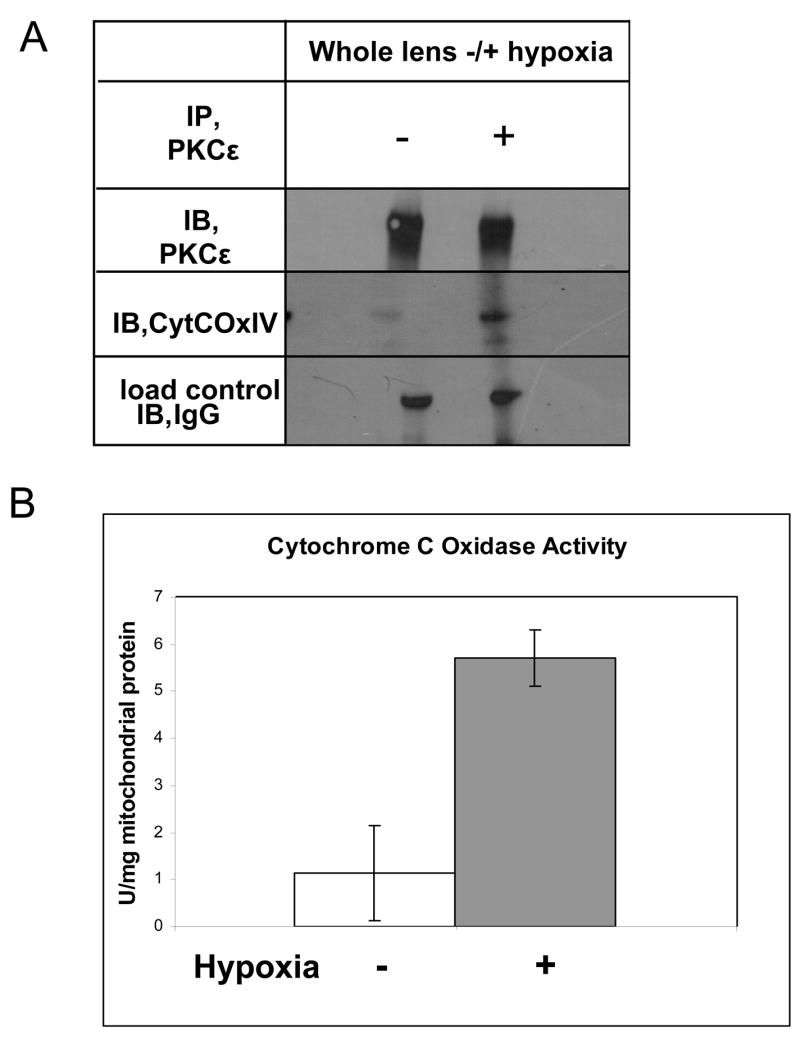

PKCε co-immunoprecipitates and co-localizes with CytCOx IV during hypoxia and this results in increased activity of CytCOx

To examine the potential interaction of PKCε with mitochondrial proteins such as CytCOx IV, co-immunoprecipitation with PKCε was used and is shown in Fig. 3A. Under normoxic conditions, in whole lenses, only a weak interaction between PKCε and CytCOx was observed. For controls, PKCε was detected in the top panel in Fig. 3A and the loading control (Immunoglobulin G, heavy chain) is shown in the bottom panel. After whole eyes were cultured in hypoxic conditions (5% oxygen) for 2 hrs, the interaction between PKCε and CytCOx was enhanced 100 fold (Fig. 3A, right side, middle panel). The protein levels of PKCε were not altered during this incubation period.

Figure 3. Analysis of Cytochrome C Oxidase IV interaction with PKCε and activity of CytCox in lenses treated with or without hypoxia.

A. Cell lysates from the control mouse lenses with or without hypoxia were used to co-immunoprecipitate PKCε and its associated protein CytCoxIV. The interaction of PKCε with CytCoxIV is sharply enhanced from hypoxia. B. Cytochrome C Oxidase activity measurements show that the enzyme is activated up to six fold in mouse lenses treated with hypoxia for two hours. IP= immunoprecipitation antisera, IB=immunoblot antisera, +/− (Hypoxia).

To measure mitochondria function, CytCOx activity was measured. CytCOx was activated under hypoxic conditions in whole lens cultures using a commercially available assay from Biochain Institute (Fig. 3B). Results demonstrate that CytCOx activity was increased by five fold after hypoxia in mouse lenses.

To further verify that PKCε can co-localize with CytCOx IV after hypoxia, confocal co-localization studies were done using N/N1003A lens epithelial cells. Figure 4 demonstrates that, under normoxic conditions, PKCε is found in a diffuse pattern throughout the cell. CytCOx is found partly localized throughout the cytoplasm. No merge between PKCε and CytCOx IV was observed under normoxic (21% oxygen) conditions.

In contrast, under hypoxia, the PKCε was less diffuse and showed a strong co-merge with CytCOx IV (yellow merge, bottom right panel). Merge was not 100% as some green (PKCε) and red (CytCOx IV) was observed.

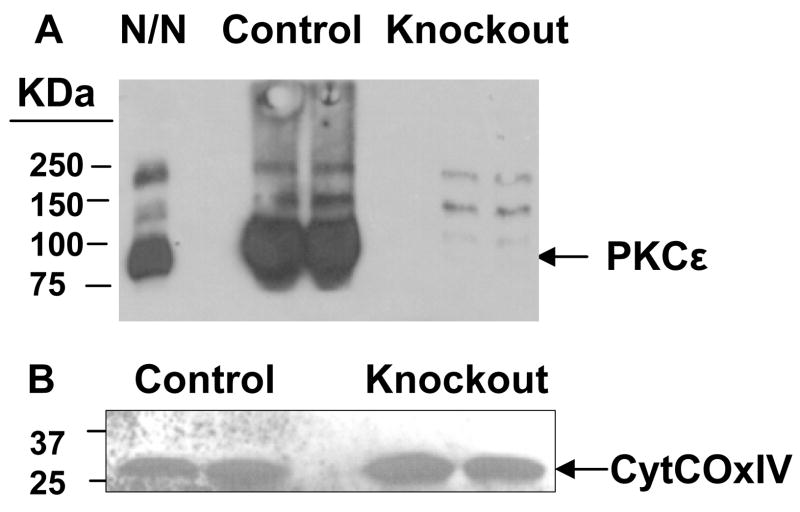

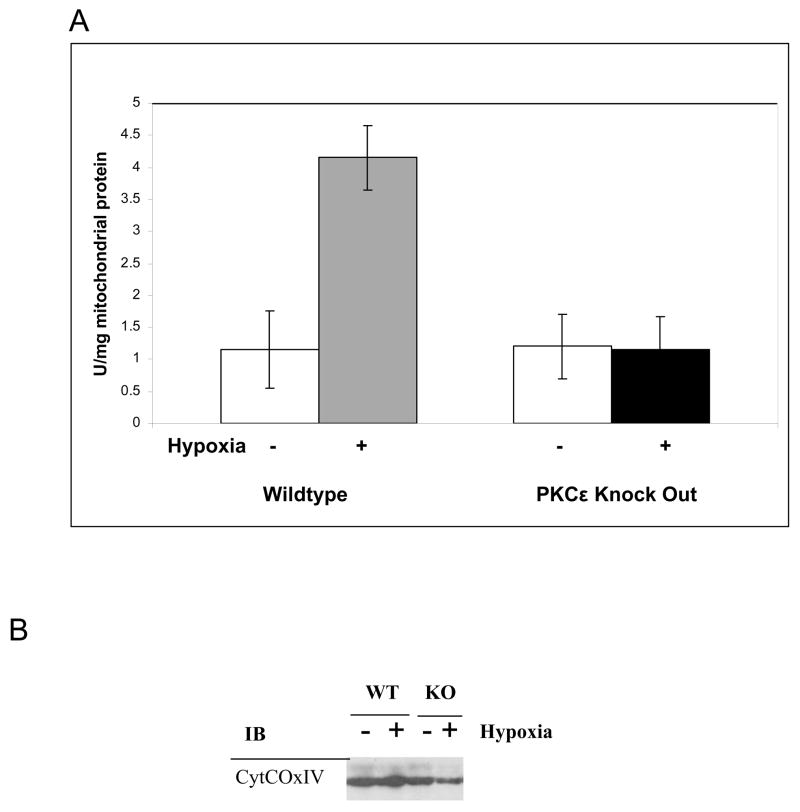

CytCOx activity is not increased after hypoxia in lenses from the PKCε knockout mice

Lenses from the PKCε knockout mice do not express this protein but have normal levels of CytCOx (Fig. 5A and B). However, although the levels of CytCOx are not altered in the knockout mouse lenses (Fig. 5,6B), this enzyme is not activated after hypoxia (Fig. 6A). Results demonstrate that the CytCOx activity remains low after hypoxia. It is not known at present if PKCε acts directly on CytCOx, or, if this enzyme initiates a cascade and remains outside the inner mitochondrial membrane.

Figure 5. PKCε and its associated protein CytCoxIV in the control and PKCε knockout mice.

Proteins of whole lens homogenates (6 weeks old) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and Western blotted using specific antisera as shown. The PKCε knockout mice used in these experiments do not contain detectable levels of PKCε (A) but do contain comparable amounts of CytCOxIV (B). N/N 1003A cell lysates were loaded in left lane. Lanes are duplicates. Upper bands are nonspecific reactions.

Figure 6. Cytochrome C Oxidase activation in the lenses of control but not PKCε knockout mice with and without hypoxia.

A. Cytochrome C oxidase enzyme activity is not increased by hypoxia in PKCε knockout mice. B. Total CytCOxIV levels in the PKCε knockout and control mice with or without hypoxia. KO, PKCε knockout; WT, wild type control mouse. All mice used at 6 weeks of age.

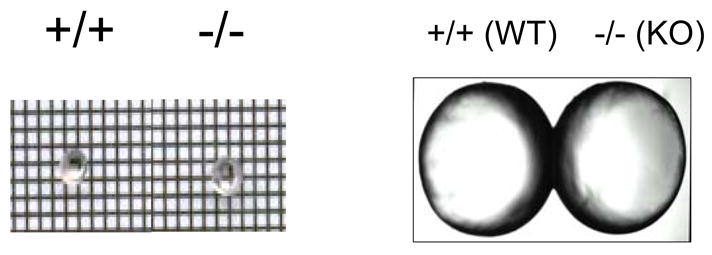

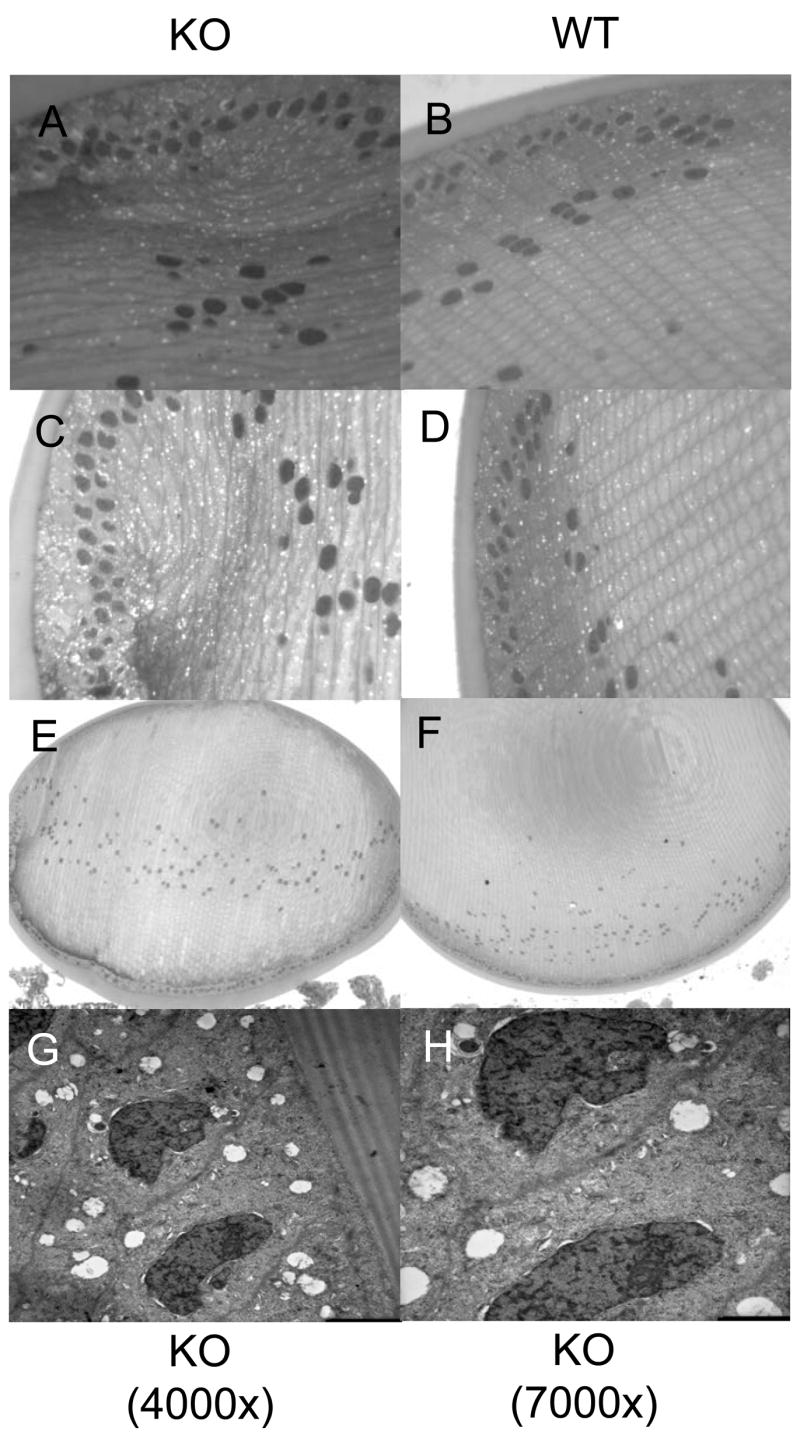

The PKCε knockout mouse lenses have altered structures in the bow region

If PKCε protects the lens during it’s naturally hypoxic state then the lenses from the knockout mice should show some structural changes. Control and PKCε knockout mouse lenses were fixed, sectioned, and examined with light or electron microscopy. The PKCε knockout lenses were not altered in size (Fig7A&B), were not cataractous, but did show altered nuclear arrangement in the bow region (Fig. 8A-F). When comparing the control with the knockout lenses more numerous and larger vacuoles were observed in the knockout mouse lenses. Fig. 8, G and H, are both PKCε knockout mice but at 4000X and 7000X. These illustrate an altered nuclear structure. A lack of mitochondria in the KO lenses suggests that these vacuoles could be where mitochondria may have been. The organization of the cells in the bow region also appeared to be altered in the PKCε knockout lenses (Fig. 8, panels E and F).

Figure 7. Wild type and PKCε knockout mouse lenses are not altered in size.

Shown are pictures of fresh mouse lens (6 week old) from WT or KO mice. A. Grid picture. B. Enlarged.

Figure 8. Structural alteration of the PKCε knockout mouse lens.

A-F. Lenses from PKCε knockout mice (KO) (A, C, and E) were compared to the control mouse lenses (WT) (B, D, and F) (6 week old). Whole lenses are pictured in E and F, at 10X. Light microscopy images of stained sections were taken at 40X (A-D). Nuclear disorganization and large numerous vacuoles were observed in the knockout lenses but not the wild type lenses. G-H. Electron microscopy images of PKCε knockout lenses at 4000X (G) or 7000X (H) show large vacuoles, distorted nuclei, and lack of mitochondria. KO, PKCε knockout; WT, wild type control mouse

Discussion

In the hypoxic environment of the lens, there exists a steep oxygen gradient that reaches a minimum at the core of the lens (McNulty et al., 2004,). Furthermore, the same report demonstrated that mitochondria account for approximately 90% of total oxygen consumption in the lens. Because oxidative damage plays a key role in cataract pathology, it has been suggested that possible hypoxic damage would have to be carefully controlled in the lens. Mitochondria are abundant in the lens, but only within the epithelium and differentiating fibers, mature fibers in the core of the lens lack mitochondria. It is important to note that about half of the lens is made up of differentiating fibers with what is considered a normal complement of organelles (McNulty et al., 2004). Therefore the maintenance of healthy mitochondria is critical to prevent lens damage during hypoxia.

Numerous studies have pointed out the importance of PKCε for mitochondrial function in heart tissue. This includes inhibition of the apoptotic protein Bad (Baines et al., 2002). Over-expression of PKC results in the inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (Baines et al., 2003), and in activation of ATP sensitive K+ channels (Jaburek et al., 2006). Mice which over-express PKCε, also have increased adenosine nucleotide translocase activity, decreased cytochrome C release, and stabilization of the inner mitochondrial membrane potential (McCarthy et al., 2005).

An important question remains: How is PKCε activated by hypoxia? Many reports suggest that PKCε is activated by reactive oxygen species production. Because decreased mitochondrial function leads to ROS production, perhaps this is the link between hypoxia and activation of PKCε. Lowered oxygen levels could cause increased accumulation of reactive oxygen species which could then activate PKCε. Another PKC isoform, PKCγ, is activated directly by hydrogen peroxide, resulting in loss of the C1B-bound zinc and formation of disulfide bonds between cysteine residues (Lin and Takemoto, 2005). Both PKCγ and PKCε have C1B domains that bind diacylglycerol resulting in enzyme activation. However, unlike other isoforms, these two PKCs can be activated directly without a calcium signal. In both PKCγ and PKCε the C1B domains are exposed and could be directly affected by increased reactive oxygen species (recently reviewed in Barnett, et al., (2007). In this report we demonstrate that lens PKCε is strongly activated, in lens epithelial cells and in whole mouse lens, by hypoxia.

Once this PKC is activated the next question would be, what is the target? It would be logical for PKCε in the naturally hypoxic lens to have mitochondrial proteins as direct targets. CytCOx is located on the inner mitochondrial membrane and it plays a critical role in cellular bioenergetics as component four of the electron transport chain. The enzyme is composed of 13 subunits and the subunits function together to transfer electrons from cytochrome C to molecular oxygen. It is essential to maintain the inner mitochondrial proton gradient and produce ATP. We demonstrate, in this paper, that PKCε activation by hypoxia results in the activation of CytCOx. This would result in more efficient mitochondria and may provide a means for the cell to deal with hypoxia. Direct proof that PKCε is involved in CytCOx activation during hypoxia comes from the PKCε knockout mice. The lenses from these mice do not have PKCε and do not show activation of CytCOx during hypoxia even though the levels of the CytCOx protein are not altered. Under hypoxia the PKCε is translocated to the mitochondrial membrane but it is not clear if PKCε enters the inner membrane or acts outside through a cascade. However, although these proteins co-immunoprecipitate and co-localize using confocal microscopy with cytochrome C oxidase IV and PKCε immunolabeling, this could be an indirect interaction. However, the lenses from the PKCε mice do show damage; large vacuoles, distorted nuclei, disorganized cellular arrangement in the bow region and a lack of mitochondria. This strongly implicates PKCε in lens as a mitochondrial protectant.

The role of mitochondria in lens homeostasis is critical, especially in the region of the differentiating fiber cell. In this region the lens must go through an organelle loss and differentiation process while in a hypoxic state. The level of oxygen used in these studies, 5%, is high as the lens is reported to have even lower levels of oxygen (McNulty, at al., 2004). Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the PKCε would always be active and present in the mitochondria in the lens. This could provide protection under hypoxic conditions and help prevent mitochondrial-linked apoptosis. This implies that elevated oxygen would be detrimental to lens through inhibition of PKCε, as one example. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that after vitrectomy lens oxygen levels are elevated and this leads to cataract formation (Beebe, et al., 2007, Giblin, et al., ARVO). It will be interesting to determine if PKCε activity is, in fact, altered after vitrectomy. This could be one biochemical target for the deleterious effects of lens elevated oxygen.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01 EY13421 to DJT

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abeliovich A, Paylor R, Chen C, Kim JJ, Wehner JM, Tonegawa S. PKCgamma mutant mice exhibit mild deficients in spatial and contextual learning. Cell. 1993;75:1263–1271. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90614-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abeliovich A, Chen C, Goda Y, Silva AJ, Stevens CF, Tonegawa S. Modified hippocampal long-term potentiation in PKC γ-mutant mice. Cell. 1993;75:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90613-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines CP, Zhang J, Wang GW, Zheng YT, Xiu JX, Cardwell EM, Bolli R, Ping P. Mitochondrial PKCepsilon and MAPK form signaling modules in the murine heart: enhanced mitochondrial PKCepsilon-MAPK interactions and differential MAPK activation in PKCepsilon-induced cardioprotection. Circ Res. 2002;90:390–397. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000012702.90501.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines CP, Song CX, Zheng YT, Wang GW, Zhang J, Wang OL, Guo Y, Bolli R, Cardwell EM, Ping P. Protein kinase Cepsilon interacts with and inhibits the permeability transition pore in cardiac mitochondria. Circ Res. 2003;92:873–880. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069215.36389.8D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett ME, Madgwick DK, Takemoto DJ. Protein kinase C as a stress sensor. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1820–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter G, Oto E, Daniel-Issakani S, Strulovici B. Constitutive presence of a catalytic fragment of protein kinase C epsilon in a small cell lung carcinoma cell line. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1910–1917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe DC, Shui Y-B, Holekamp NM, Kramer BC. The importance of the vitreous gel in protecting against nuclear cataracts. ARVO. 2007:4918. [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud VM, Westphale EM, Grigoryeva A, Beyer EC. PKC isoenzymes in the chicken lens and TPA-induced effects on intercellular communication. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:850–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Manalo DJ, Wei G, Rodriguez ER, Fox-Talbot K, Lu H, Zweier JL, Semenza GL. Hearts from rodents exposed to intermittent hypoxia or erythropoietin are protected against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2003;108:79–85. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078635.89229.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenni V, Doppler H, Sonnenburg ED, Maraldi N, Newton AC, Toker A. Regulation of novel protein kinase C epsilon by phosphorylation. Biochem J. 2002;363:537–545. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa AD, Jakob R, Costa CL, Andrukhiv K, West IC, Garlid KD. The mechanism by which the mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channel opening and H2O2 inhibit the mitochondrial permeability transition. JBiol Chem. 2006;281:20801–20808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson RD, Vondriska TM, Biederman KJ, Zhang J, Jones RC, Zheng Y, Allen DL, Xiu JX, Cardwell EM, Pisano MR, Ping P. Protein kinase C epsilon signaling complexes include metabolism- and transcription/translation-related proteins: complimentary separation techniques with LC/MS/MS. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:421–433. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m100036-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitel K, Staiger H, Rieger J, Mischak H, Brandhorst H, Brendel MD, Bretzel RG, Haring HU, Kellerer M. Protein kinase C delta activation and translocation to the nucleus are required for fatty acid-induced apoptosis of insulin-secreting cells. Diabetes. 2003;52:991–997. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giblin F, Quriam PA, Leverenz VR, Baker RM, Loan D, Trese MT. Enzymatic liquefaction of vitreous humor in the rat in vivo increases lens nuclear pO2. ARVO. 2007:4917. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Ueyama T, Kajimoto T, Yagi K, Kohmura E, Saito N. Involvement of gamma protein kinase C in estrogen-induced neuroprotection against focal brain ischemia through G protein-coupled estrogen receptor. JNeurochem. 2005;93:883–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaburek M, Costa AD, Burton JR, Costa CL, Garlid KD. Mitochondrial PKC epsilon and mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channel copurify and coreconstitute to form a functioning signaling module in proteoliposomes. Circ Res. 2006;99:878–883. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000245106.80628.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Lorenzo PS, Bogi K, Blumberg PM, Yuspa SH. Protein kinase Cdelta targets mitochondria, alters mitochondrial membrane potential, and induces apoptosis in normal and neoplastic keratinocytes when overexpressed by an adenoviral vector. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8547–8558. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Takemoto DJ. Oxidative activation of protein kinase Cgamma through the C1 domain. Effects on gap junctions. JBiol Chem. 2005;280:13682–13693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Barnett M, Lobell S, Madgwick D, Shanks D, Willard L, Zampighi GA, Takemoto DJ. PKCε knockout mouse lenses are more susceptible to oxidative stress damage. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:4371–4378. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Shanks D, Prakash O, Takemoto DJ. Protein kinase C γ mutations in the C1B domain cause caspase-3-linked apoptosis in lens epithelial cells through gap junctions. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J, McLeod CJ, Minners J, Essop MF, Ping P, Sack MN. PKCepsilon activation augments cardiac mitochondrial respiratory post-anoxic reserve--a putative mechanism in PKCepsilon cardioprotection. JMol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:697–700. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty R, Wang H, Mathias RT, Ortwerth BJ, Truscott RJW, Bassnett S. Regulation of tissue oxygen levels in the mammalian lens. JPhysiol. 2004;559:883–898. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. Studies and perspectives of protein kinase C. Science. 1986;233:305–312. doi: 10.1126/science.3014651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbi M, Johnson JA. Protein kinase Cepsilon interacts with cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV and enhances cytochrome C oxidase activity in neonatal cardiac myocyte preconditioning. Biochem J. 2006;393:191–199. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz A, Jonsson JI, Larsson C. The regulatory domain of protein kinase C theta localises to the Golgi complex and induces apoptosis in neuroblastoma and Jurkat cells. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:662–675. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitaler M, Cantrell DA. Protein kinase C and beyond. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:785–790. doi: 10.1038/ni1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidman R, Troller U, Raghunath A, Pahlman S, Larsson C. Protein kinase Cepsilon actin-binding site is important for neurite outgrowth during neuronal differentiation. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:12–24. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-04-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]