Abstract

Antimicrobials were first introduced into medical practice a little over 60 years ago and since that time resistant strains of bacteria have arisen in response to the selective pressure of their use. This review uses the paradigm of the evolution and spread of beta-lactamases and in particular beta-lactamases active against antimicrobials used to treat Gram-negative infections. The emergence and evolution particularly of CTX-M extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) is described together with the molecular mechanisms responsible for both primary mutation and horizontal gene transfer. Reference is also made to other significant antibiotic resistance genes, resistance mechanisms in Gram-negative bacteria, such as carbepenamases, and plasmid-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance. The pathogen Staphylococcus aureus is reviewed in detail as an example of a highly successful Gram-positive bacterial pathogen that has acquired and developed resistance to a wide range of antimicrobials. The role of selective pressures in the environment as well as the medical use of antimicrobials together with the interplay of various genetic mechanisms for horizontal gene transfer are considered in the concluding part of this review.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, MRSA, ESBL, plasmids, beta-lactamases

Introduction

One of the greatest contributions to modern medicine has been the development of effective safe antimicrobial treatments. Although the introduction of sulphonomides in the 1930s led to marked reductions in infections due to Streptococcus pyogenes and pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, resistance appeared very rapidly, and it was the introduction during the Second World War of benzyl penicillin that had the most dramatic impact on these infections, together with the ability to treat serious infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Coincident with the first clinical use and description in the literature of penicillin to treat S. aureus infections, the group that developed penicillin in Oxford reported in Nature on an enzyme produced by Escherichia coli that was capable of hydrolysing penicillin; they coined the term ‘penicillinase' (Abraham and Chain, 1940). Penicillinase production in staphylococci was described a little later (Kirby, 1944), spreading rapidly such that by the late 1940s approximately 60% of S. aureus in the UK were positive (Figure 1). This illustrated a fundamental observation in the science of antimicrobial resistance: that the possession of antimicrobial resistance genes does not necessarily put organisms at a disadvantage. In the 1950s, strains of S. aureus rapidly accumulated resistance to tetracycline, macrolides and aminoglycocides, posing considerable problems in the management of nosocomial infection caused by this organism. The problem of these resistant strains was largely solved by the development of penicillinase-stable penicillins such as methicillin and the more clinically useful derivatives, cloxacillin and flucloxacillin. Disappointingly, within 1 year of the introduction of methicillin, the first methicillin resistant to S. aureus (MRSA) was detected and the first clinical failure was described at the same time (Jevons, 1961). The subsequent rise in the 1980s of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) throughout the world has caused further problems in antimicrobial therapy, and the much feared emergence of high-level vancomycin resistance in S. aureus encoded by the vanA gene has been very slow to appear, with only a handful of isolates reported to date. Following the introduction of penicillin, many Gram-negative infections remained difficult to treat, as the only agents available with significant activity against Enterobacteriaceae throughout the 1950s were tetracycline, chloramphenicol and streptomycin. This position, however, was revolutionized by the development of semi-synthetic penicillins by the Beechams company, in which the core beta-lactam nucleus (6-amino penicillinamic acid) was attached chemically to synthetic side chains. The first compound to really influence treatment was ampicillin, a compound active against most Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae (Rolinson, 1998). The rapid rise of resistance to ampicillin in the early 1960s turned out to be due to a plasmid mediated beta-lactamase, one of the first described in Gram-negative bacteria, known as TEM. The industry responded by developing a more sophisticated beta-lactam compounds resistant to hydrolysis by TEM and SHV beta-lactamases, the so-called third-generation cephalosporins (e.g. cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone). The further selection of resistant mutants and the acquisition of novel antibiotic resistance genes from environmental bacteria led, in turn, in the late 1980s and 1990s to the appearance of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), which now compromise the use of third-generation cephalosporins for the treatment of serious Gram-negative infections. The industry further responded with the introduction through the 1990s of carbapenems, which are extremely stable to degradation by all Gram-negative beta-lactamases, which seemed to be the answer. However, Darwinian principles of evolution are very evident among bacterial populations and the selection and spread of a variety of beta-lactamases capable of hydrolysing carbapenems are seen increasingly in clinical isolates of Gram-negative bacteria (Walsh et al., 2005). We now have a situation in Gram-negative bacteria where a wide range of mechanisms of resistance encoded by a plethora of genes, many of which are highly mobile, pose substantial problems in the treatment of Gram-negative infections (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Rapid spread of penicillin production among S. aureus strains in the London region (data from Barber and Rozwadowska-Dowzenko, 1948).

Table 1. Some important antibiotic resistance genes posing threats to the clinical infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria.

| Antibiotic resistance genes | Antibiotics compromised |

|---|---|

| ESBL genes (e.g. blaTEM/CTX-M/ SHV) | Third-generation cephalosporins (e.g. cefotaxime, ceftazidime), monobactams (e.g. aztreonam) |

| Plasmidic AmpC genes (e.g. blaCMY/FDX/DHA/ACT) | Third-generation cephalosporins cephamycins (e.g. cefotoxin, cefotetan), monobactams |

| Carbapenemase genes (e.g. blaIMP/VIM/KPC) | Third-generation cephalosporins, carbapenems |

| Mutated gyrA/B, aac (6′)-Ib-cr, qnrA/B | Fluoroquinolones |

| ‘Efflux genes' (e.g. acrA/B, mexA/B) | Wide range of antibiotics, particularly tetracyclines, quinolones, chloramphenicol, some beta-lactams |

| ‘Intrinsically resistant bacteria' (e.g. Stenotrophomonas maltiphilia carrying a range of chromosomal beta-lactamases combined with loss of outer membrane porins) | Almost all antimicrobials |

It is the purpose of this review to focus, in particular, on the evolution and spread of resistance to third-generation cephalosporins as a paradigm for the molecular epidemiology of Gram-negative antibiotic resistance genes and to only touch on some of the other important resistance genes in Gram-negative bacteria. In the Gram-positive arena, MRSA arguably remains the greatest challenge to specialists in infection, and the current situation will be briefly reviewed. Finally, the issue of sources and routes of movement and selection of antibiotic resistance genes in the wider environment will be reviewed and likely future trends will be described.

The emergence and evolution of ESBL

Something in excess of 400 beta-lactamases have now been described, and these are curated by Dr George Jacoby and Dr Karen Bush through a website (www.lahey.org/studies/webt.asp). The most frequently used classification of beta-lactamses is based upon DNA sequence following the suggestions of Ambler (1980). Beta-lactamases under this classification are divided into four groups of which groups A, C and D have serine moieties at their active site, whereas group B enzymes have zinc molecules at the active site. The group A enzymes are a large family, including staphylococcal penicillinase, TEM, SHV and CTX-M Gram-negative beta-lactamases, as well as a number of other rarer enzymes that often exhibit ESBL activity (e.g. GES, VEB, etc.). The Ambler group C beta-lactamases are chromosomal beta-lactamases found mainly in Enterobacteriaceae that have also now become mobilized onto plasmids, the most notable of which are the CMY series (Philippon et al., 2002). Group D enzymes are characterized by their oxacillinase activity, and some have been found to have marked carbepenamase activity and are now being intensively studied. Others have broad-spectrum activity against both cephalosporins and penicillins and are not inhibited by conventional beta-lactamase inhibitors such as clavulanic acid and tazobactam and are responsible for the inhibitor resistance seen in many British isolates of CTX-M producing E. coli.

One of the most widely distributed beta-lactamases is the TEM beta-lactamase, which catalyses the hydrolysis of ampicillin and related antimicrobials such as piperacillin, carbenacillin. It was biochemically characterized in 1966, and the strain that was studied had been isolated earlier from a patient in Greece. The beta-lactamase was noted to be associated with a transferable plasmid (then designated an R factor) (Datta and Richmond, 1966). The TEM beta-lactamase gene became rapidly disseminated among different species of Enterobacteriaceae as evidenced by the results of a survey of E. coli in the faeces of patients presenting for elective surgery in West London in 1968, when 17% carried plasmid-mediated ampicillin resistance (Datta, 1969). TEM beta-lactamase spread not only among Enterobacteriaceae but into Pseudomonas aeruginosa and, subsequently, in 1974 was reported from Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria gonnorhoeae (Brunton et al., 1986). The pharmaceutical industry proceeded to develop third-generation cephalosporins such as cefotaxime and ceftazidime, which were stable to hydrolysis by TEM and the closely related SHV-type beta-lactamases. Third-generation cephalosporins are marked by the inclusion of an oxyimino-amino thiazolyl side chain that interfered with access of the molecule to the active site of the beta-lactamase. Cefotaxime was the first widely used third-generation cephalosporin and was introduced in the early 1980s; however, by 1983, there was a report of plasmid-mediated resistance to that agent (Knothe et al., 1983). In this particular case, the gene encoding the SHV-1 beta-lactamase that is widely distributed among Enterobacteriaceae and is carried normally on the chromosome of Klebsiella pneumoniae acquired a point mutation altering the confirmation of the beta-lactamase molecule, allowing hydrolysis of cefotaxime and related third- and second-generation cephalosporins, the gene involved being named blaCTX−1. This first report was closely followed by a report from France of plasmid-mediated resistance to third-generation cephalosporins. It was quickly discovered that the enzyme originally designated CTX-1 was in fact a derivative of TEM beta-lactamase and was renamed TEM-3 (Kitzis et al., 1988). Over the next 10 years or so, TEM- and SHV-derived beta-lactamases became moderately common and well distributed, particularly among Klebsiella spp. In a survey of intensive care units in Europe undertaken in 1994, it was shown that of third-generation resistant isolates of klebsiellae in France 24% carried the ESBL phenotype, and in Turkey 59% and in Portugal 49%. This is in marked contrast to the findings in the UK and Spain, where 0 and 1% isolates carried the ESBL phenotype (Livermore and Yuan, 1996). This paucity of ESBLs in the UK in the early 1990s was further confirmed by a countrywide study of 3951 unselected isolates collected in 1990–91, which revealed a 1% rate for the ESBL phenotype, while finding some SHV-derived ESBLs did not find any TEM-derived ESBLs (Piddock et al., 1997). TEM-based ESBL genes have continued to evolve by mutation, and on 8th May 2007, 160 molecular variants were described and documented on the Lahey Hospital website. Generally, TEM-/SHV-derived ESBLs are most frequently found in klebsiellae, but numerous outbreaks around the world have demonstrated that they can be found in most other species of Enterobacteriaceae and are particularly responsible for outbreaks that are often nosocomial. The evolution of TEM ESBLs can be complicated, and an example of convergent evolution of some common TEM ESBL genotypes has been reported (Hibbert-Rogers et al., 1994). SHV-type ESBLs in a similar way to TEM-derived ESBL genes are evolving by mutation (108 different genotypes reported on the Lahey Hospital website, 8th March 2007). The relationship of some of the most common SHV ESBLs has been reviewed and demonstrates both converging and diverging evolutionary relationships (Heritage et al., 1999).

In K. pneumoniae, the SHV-type ESBLs through the 1990s were successful and widely distributed as shown by a survey from seven countries (South Africa, Argentina, Australia, Turkey, USA, Taiwan and Belgium), occurring in 49/73 of the isolates collected in 1996/7 from all of the countries, SHV-5 being the most common genotype (Paterson et al., 2003). Overall data on the distribution of ESBLs in China was patchy during that time; the SHV-2 genotype was reported as long ago as 1998 (Jacoby et al., 1988). There is a further report of SHV-2 type in 1994 (Cheng et al., 1994). The frequency of occurrence of the ESBL phenotype in China was, however, well recognized in the late 1990s as being common; a rate of 27% of E. coli and Klebsiella recovered from blood cultures in Beijing being reported (Du et al., 2002). As part of a WHO collaboration, I was privileged to work with Dr Jianhui Xiong and her colleagues at the First Municipal People's Hospital in Guangzhou, when 15 isolates of Enterobactericeae selected as representative of ESBL isolates from that hospital were fully genotyped. The surprising finding was that four different species were found to carry ESBL genes, namely E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae and Citrobacter freundii. SHV-12—an enzyme that is not uncommon in the Far East—was found, but more surprising was the discovery that 13 of the 15 isolates carried CTX-M-type beta-lactamases. Two of the three genotypes identified (CTX-M-13 and -14) were novel, and these represented the first descriptions of these novel genes, CTX-M-14 being one of the two most common genotypes worldwide (Chanawong et al., 2002). CTX-M beta-lactamases have evolved from an entirely different route to the SHV/TEM ESBLs in that they represent the movement of a chromosomal beta-lactamase found in different species of Kluyvera spp. into plasmids, which are then presumed to have transferred by conjugation into Klebsiella and E. coli (Poirel et al., 2002). CTX-M beta-lactamases can be identified as arising from three different species of Kluyvera, namely Kluyvera georgiana, which is thought to be the progenitor of the CTX-M-8 and -9 group enzymes; Kluyvera ascorbata, which is thought to be the progenitor of CTX-M-1 and -2 group enzymes as well as CTX-M-3, is also thought to have arisen from K. ascorbata. Kluyvera cryocsrescens was found to share an 86% amino-acid identity with CTX-M enzymes of the CTX-M-1 group, and, although the identify is not as close as it is with K. ascorbata, for CTX-M-1 group, it is quite likely that it was the source of genes in some of the CTX-M-1 group carrying plasmids (Decousser et al., 2001). CTX-M ESBLs are borne on plasmids that enable the genes to be transferred from one bacterial species to another and from one genus to another; the plasmids on which various CTX-M genes are borne are incompatibility groups Inc-FI, FII, FH12 and Inc1. These are of narrow host range within the Enterobacteriaceae; however, some genes have also been described on Inc–N, Inc -P-1 and Inc L/M plasmids (Novais et al., 2006). Recently, one of the highly successful CTX-M-15-type-carrying plasmids has been sequenced and was found to be a member of the IncF2 broad host range plasmids, as indeed other CTX-M-15-carrying plasmids have also been identified to belong to them (Boyd et al., 2004). A number of other reports involving dissemination of Inc-12 and Inc -P1 plasmids with blaCTX−M have been published (Canton and Coque, 2006). The mobilization and dissemination of many of the CTX-M genes is achieved through an interesting single-ended transposition model involving two insertion sequences that flank the beta-lactamase, namely ISEcp1B and IS903 (Lartigue et al., 2006). This rolling circle transposition process involves the participation of both elements and is responsible for the dissemination of blaCTX−M−15/−14, particularly. Class 1 integrons of CR1 (formerly called orf513) have been recognized to be important in moving CTX-M-1, -2 and -9 groups of blaCTX−M (Canton and Coque, 2006). ISCR1 is recognized as a very important element in the mobilization of many different antibiotic resistance genes, including plasmid-mediated ampC beta-lactamase genes (Toleman et al., 2006). Broadly different genotypes are often associated with different mobilization mechanisms; CTX-M-9, for instance, has been frequently associated with the ISCR1-type elements that contain class 1 integrons, whereas the widely distributed bla-CTX-M-14 and bla-CTX-M-15 are associated with ISEcp1 mobilizing mechanisms. The genes that are associated with the ISEcp1-like family of insertion sequences are also frequently expressed at a higher level and this has been shown for CTX-M-14, -18, -17 and -19 (Poirel et al., 2005).

MRSA

In the case of Gram-positive nosocomial pathogens, S. aureus reigns supreme. Ever since the earliest days of the introduction of penicillin, resistance appeared rapidly within S. aureus mediated by the enzyme penicillinase (Figure 1). S. aureus that produce penicillinase would seem to have a substantial advantage over those that are sensitive in that approximately 90% of all isolates of S. aureus both within hospitals and within the community produce penicillinase and are therefore resistant not only to benzyl penicillin, but also to drugs such as methicillin, piperacillin and first-generation cephalosporins (Henwood et al., 2000). Initially, beta-lactamase production was plasmid mediated and frequently linked to cadmium resistance, but there is evidence that the gene is sometimes chromosomally located (Lacey, 1975). The genes are under a complex system of control, as there are a cluster of genes: bla Z, bla R1 and bla I, which encode, respectively, the beta-lactase itself (bla Z), a repressor molecule (bla I) and a signal transducer (anti-repressor, bla R1) (Safo et al., 2005). Penicillinase-producing hospital strains that were also resistant to tetracyclines, macrolides and frequently aminoglycosides such as streptomycin became particularly common in the 1950s, and especially important in the UK were clones belonging to the 80/81 phage type. These problems of large-scale cross-infection with S. aureus were solved by the introduction of methicillin and later the semi-synthetic penicillins cloxacillin and flucloxacillin, leading to a decline in these strains (Parker, 1966). Not long after the introduction of methicillin, three resistant isolates were noted from the same hospital in southern England and this marked the appearance of MRSA (Jevons, 1961). In many industrialized nations and parts of the Far East, 40–60% of all hospital isolates of S. aureus are now resistant to penicillin (MRSA) (Fluit et al., 2001). Following the first appearance of MRSA in the early 1960s, MRSA did not spread particularly fast, and it was not until the late 1980s and 1990s that MRSA became the major problem that it has become. The second wave of MRSA infections following the initial appearance started in the late 1970s, first in Australia, the Irish Republic and USA, since when rates of MRSA have increased in virtually all countries with a few notable exceptions such as the Netherlands and Denmark (Diekema et al., 2001). The intercontinental spread of MRSA in these two waves has been reviewed elsewhere (Ayliffe, 1997). In the UK, particular clones have become exceptionally common and have been referred to as epidemic MRSA (EMRSA). EMRSA-1 was isolated in a London hospital in 1981 and then spread to other hospitals in London and the South East (Duckworth et al., 1988). Seventeen EMRSA strains have been described subsequently (Aucken et al., 2002), the two most commonly encountered being EMRSA-15 and -16. There has been a steady rise in the number of reports of EMRSA-15 and -16 so that they are now responsible for more than 95% of all MRSA bacteraemias in the UK (Moore and Lindsay, 2002). EMRSA-16 is largely concentrated in the southern half of the UK but can also be found elsewhere, whereas EMRSA-15 is found in the north and Midlands. S. aureus strains that are resistant to isoxyl penicillins, which are stable to staphylococcal penicillinase, possess a completely different mechanism whereby the enzymes (penicillin-binding proteins) that are responsible for placing the cross-links in long peptoglycan monomer chains that are normally inhibited by beta-lactam antibiotics are circumvented by the presence of an additional gene encoding a penicillin-binding protein (PBP) that is no longer inhibited by methicillin/cloxacillin. The accessory PBP is referred to as PBP2A, the gene is not carried on a plasmid but is present on a mobile genetic element referred to as the staphylococcal cassette chromosome (SCCmec), which carries a range of genes, including the mecA gene, which confers resistance to methicillin-related antibiotics (Utsui and Yokota, 1985). Despite the SCCmec complex carrying resistance genes active against some other non-beta-lactam antibiotics and the fact that most MRSA strains are also resistant to fluoroquinolones by virtue of the possession of mutations in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene, MRSA has remained highly susceptible to vancomycin. Intermediate levels of resistance were first reported in Japan in 1996 and have since been reported from a number of countries around the world (Hiramatsu, 1998). The exact mechanism by which vancomycin intermediate S. aureus isolates become resistant to vancomycin remains unclear, but it is most likely that it involves a thickening of the cell wall due to the accumulation of cell wall fragments capable of binding vancomycin extra-cellularly and changes in several metabolic pathways that slow cell growth (Cui et al., 2000). Clinically, these strains may result in failed treatment with vancomycin, but because the level of resistance is comparatively low (typical minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) 8 mg l−1), there is some doubt as to their clinical significance. Noble et al. (1992) had demonstrated many years ago that the vanA gene from Enterococcus faecalis, which is present on a conjugative transposon, was capable of transfer into some strains of S. aureus and then being expressed, leading to very high MICs of vancomycin (⩾256 mg l−1). This was the most feared mechanism of resistance to vancomycin in S. aureus and, bearing in mind that MRSA and vancomycin-resistant enterococci frequently co-exist in patients treated with vancomycin in a hospital setting, it seemed inevitable that vancomycin-resistant S. aureaus would emerge. It was not until 2002 that the first strain was identified in the USA (Chang et al., 2003). The patient was a woman from Michigan who had diabetes mellitus, hypertension and peripheral vascular disease as well as chronic renal failure and developed chronic foot ulcers that were infected with MRSA. Subsequent MRSA bacteraemia arising from an abscess associated with a graft for dialysis access led to a long period of treatment lasting a total of 6½ weeks with vancomycin over a 6-month period. A culture from a heel ulcer grew a strain of MRSA with an MIC of 1024 mg l−1 vancomycin but remained susceptible to other agents such as linezolid, trimethoprim/sulphamethoxazole and quinupristin-dalfopristin. Analysis of the vancomycin-resistant S. aureus isolate revealed the multi-resistant conjugative plasmid on which the tranposon Tn1546 carrying the vanA resistance gene determinant and associated genes had integrated into the genome of that strain (Weigel et al., 2003). Other genes conferring resistance to trimpethoprim, beta-lactams and aminoglycosides were also identified on the plasmid and had been present in similar plasmids of preceding isolates of MRSA from the patient, which had been isolated from earlier times. It was therefore assumed that a pre-existing plasmid of MRSA had received the vanA transposon from a comensal vancomycin-resistant enterococci strain present at the same infection site and that the selection pressure exerted by the vancomycin had resulted in the transfer. There have now been a number of reports from the USA between 2002 and 2006 where six vancomycin-resistant S. aureus strains carrying the vanA gene complex have been reported, therefore being evidence that the genetic mechanisms by which the transfers occurred were distinct and often different to each other (Appelbaum, 2006). Worryingly, vancomycin-resistant S. aureus has also been reported recently from India where two strains were found in a recent survey (Tiwari and Sen, 2006). The delay in the emergence of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus may well be explained by the fact that many lineages of S. aureus identified by multi-locus sequence typing carry a specific restriction system (sau type 1 restriction modification system) that destroys incoming DNA, thus making it difficult for foreign DNA from bacteria such as enterococci to enter the cell and replicate (Waldron and Lindsay, 2006). MRSA are usually thought of as being associated purely with hospitals, but more recently transmission of community-acquired strains has been reported, particularly from North America, and this represents a growing challenge to the treatment of community S. aureus infections (Maltezou and Giamarellou, 2006).

It was in North America that community-acquired MRSA were first noticed, and in some parts now rates have risen to as much as 70% of isolates of S. aureus (Mishaan et al., 2005). Outbreaks have been seen particularly among inmates of jails and in sports facilities. Many of these strains also carry genes encoding the Panton Valentine Leukocidin toxin gene. Expression of this toxin leads to severe necrotizing fasciitis and haemorrhagic respiratory infection; the activity of this pathogenicity gene has recently been demonstrated in an animal model (labanderia-rey science 2007). Unlike most nosocomial strains of MRSA, community-acquired MRSA strains are frequently susceptible to antimicrobials such as clindomycin, tetracyclines, gentamicin, trimepthoprim/suphamethoxazole, fluoroquinolones and chloramphenicol. However, growing levels of resistance is increasing the prospect of a multi-resistant community-acquired MRSA that might acquire the vanA gene, a real cause for considerable concern.

More recently, companion animals such as cats, dogs and horses have been noted to carry both human-type MRSA as well as specific animal-associated strains of MRSA. There is also concern that MRSA strains have now been identified in animals that are eaten and there has been evidence of spread to humans, particularly in pigs in the Netherlands (de Neeling et al., 2007). In Germany and Austria, one particular dog-, pig- and horse-associated strain of a clonal lineage sequence type 398 has been described (Loeffler et al., 2005; Witte et al., 2007).

In summary, it seems likely that not only will MRSA continue to increase in prevalence in both the community and hospitals, but there will be increasing problems of antimicrobial resistance. This may well be alleviated by the introduction of a number of potent antibiotics that are active against MRSA, such as ceftobiprole (Noel, 2007), tigecycline (Hawkey and Finch, 2007), novel quinolones (Wang et al., 2007), and newer derivatives of glycopeptides such as oritavancin that are not susceptible to vanA-mediated resistance mechanisms (Allen and Nicas, 2003).

Conclusions

Antimicrobial agents have a wide range of modes of action ranging from interference with cell wall synthesis, inhibition of prokaryotic protein synthetic inter-cellular machinery, nucleic acid synthesis and inhibition of prokaryote-specific metabolic pathways (Hawkey, 1998). However, bacteria by virtue of both their rapid growth rate such that favourable mutations become very rapidly selected and their access to a wide range of genetic material through horizontal gene transfer can develop resistance—and have developed resistance—to all known classes and groups of antimicrobial agents by a plethora of mechanisms (Hawkey, 1998). Mechanisms of horizontal gene transfer centre around three main means: conjugation, transduction and transformation. During conjugation, particularly Gram-negative bacteria acquire a double-stranded circular piece of DNA that is capable of autonomous replication within the bacterial cell via an elongated proteinatious structure termed a pilus, which conjoins the two organisms. Conjugative plasmids are also capable of capturing chromosomal genes and mobilizing smaller non-transferable plasmids providing a ‘bridge' from the general environment into medically important bacteria (Szpirer et al., 1999). Many antibiotic resistance genes in Gram-negative bacteria are also carried on transposons (genetic elements capable of replicative transfer between plasmids and/or the chromosome). A further level of capture and expression is provided by integrons, genes such as blaCTX−M being frequently carried on these structures (Boucher et al., 2007). Conjugation in Gram-negative bacteria is replicative process and the recipient bacterium acquires a new copy of the transferred plasmid, which is still retained by the donor isolate. Conjugation can also occur amongst Gram-positive bacteria and is usually initiated by the production of sex pheromones, which facilitate the clumping of donor and recipient organisms allowing the exchange of DNA. This process is particularly common in Gram-positive bacteria when conjugative transposons, which are elements found on plasmids and the bacterial genome, replicate and transfer; the vanA resistance gene is carried on such a transposon. During transduction, resistance genes are packaged into bacterial phages (bacterial viruses) and then released in a new strain following infection by the bacterial phage. This process is probably quite important among S. aureus, which has barriers to the receipt of both conjugative transposons and incoming DNA. Transformation is a very important process particularly amongst S. pneumoniae, N. gonorrhoeae, and Neisseria meningitidis. This process involves the uptake of naked DNA via the cell wall, which is in a condition known as competent, and the incorporation of that DNA into the existing genome or plasmids. Penicillin resistance as seen in pneumococci is conferred by DNA sequences of penicillin-binding proteins that have been acquired from commensal streptococcal species, presumably in the naso-pharynx of patients infected with pneumococci, the genes being identified as having a mosaic structure.

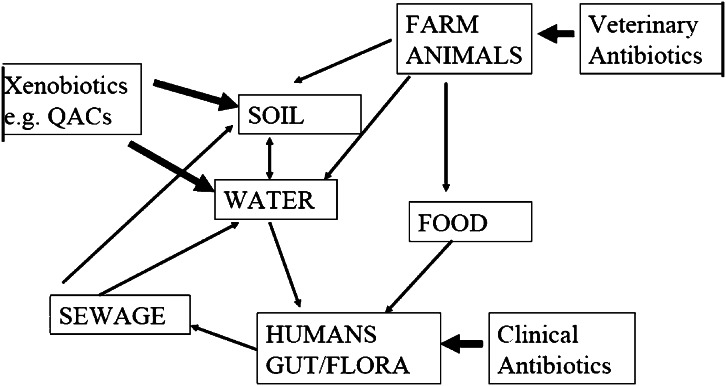

We live in a microbiologically interlinked world in which resistance genes from animals that are eaten can colonize our bowel flora, which are then excreted and, via the sewerage system, can find their way back into the land. We also have cycling of bacteria and hence resistance genes in hospitals and in the community of resistant strains by both contact and through other routes, such as the faeco-oral route. There is also selective pressure applied not only by the medical use of antibiotics, but also by the agricultural use of antibiotics, and there is even evidence that some compounds not thought of as having antimicrobial activity, such as quaternary ammonium compounds used in fabric conditioning, can select for antibiotic resistance genes (Gaze et al., 2005). This complex system of interlocking cycles of transmission is represented in Figure 2. Examples of the movement of resistance genes either from humans to animals or vice versa are found: a cause for concern is the recent finding of CTX-M resistance genes in E. coli in chicken meat imported from different parts of the world to the UK, in which particular genotypes noted in human patients such as CTX-M-2 in South America were found in 50% of imported pre-prepared chicken breasts from Brazil (Ensor et al., 2007). There are also pressures to use antimicrobials both by the commercial exploitation and development of antimicrobials and by the humanitarian desire to treat infected humans and animals. We live in a world in which there is greater mobility of people and food and other goods that leads to the greater probability of the spread of resistant clones of bacteria that might emerge in distant locations. If one looks at the carriage of CTX-M beta-lactamase genes in the faecal flora of the community in China and India, there are estimates that this may be as high as 10%, and with a combined population of 2.5 billion, this must represent the largest reservoir of antimicrobial resistance genes capable of conferring resistance to important antibiotics used to treat Gram-negative infection (Ensor et al., 2006; Ling et al., 2006). It is only through the prudent use of antimicrobial drugs and the introduction of new and effective agents particularly against multi-drug-resistant strains as a worldwide effort that the march of antibiotic resistance will be slowed down. We should always be aware that in geological time we have only had effective antimicrobial therapy for infections for a fraction of a second, and it is important that we continue to have the facility to continue to treat serious bacterial infections.

Figure 2.

Flow of antibiotic resistance genes in E. coli in the biosphere.

Acknowledgments

I thank Mrs Jane Moore for her untiring work to help produce this manuscript and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, and the Department of Health for support for some of the work cited in this review.

Glossary

- EMRSA

epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- ESBL

extended-spectrum beta-lactamase

- MRSA

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Professor Hawkey has received research funding and/or speaker support from Astra Zeneca, Basilea, Bayer, Beckton Dickinson, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer and Wyeth.

References

- Abraham C, Chain E. An enzyme from bacteria able to destroy penicillin. Nature. 1940;146:837–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NE, Nicas TI. Mechanism of action of oritavancin and related glycopeptide antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;26:511–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2003.tb00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambler RP. The structure of beta-lactamases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1980;289:321–331. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PC. The emergence of vancomycin-intermediate and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12 Suppl 1:16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aucken HM, Ganner M, Murchan S, Cookson BD, Johnson AP. A new UK strain of epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (EMRSA-17) resistant to multiple antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50:171–175. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayliffe GA. The progressive intercontinental spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24 Suppl 1:S74–S79. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber M, Rozwadowska-Dowzenko M. Infection by penicillin-resistant staphylococci. Lancet. 1948;2:641–644. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(48)92166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher Y, Labbate M, Koenig JE, Stokes HW. Integrons: mobilizable platforms that promote genetic diversity in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd DA, Tyler S, Christianson S, McGeer A, Muller MP, Willey BM, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of a 92-kilobase plasmid harboring the CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase involved in an outbreak in long-term-care facilities in Toronto, Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3758–3764. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3758-3764.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunton J, Clare D, Meier MA. Molecular epidemiology of antibiotic resistance plasmids of Haemophilus species and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:713–724. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.5.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canton R, Coque TM. The CTX-M beta-lactamase pandemic. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanawong A, M'Zali FH, Heritage J, Xiong JH, Hawkey PM. Three cefotaximases, CTX-M-9, CTX-M-13, and CTX-M-14, among Enterobacteriaceae in the People's Republic of China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:630–637. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.630-637.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Sievert DM, Hageman JC, Boulton ML, Tenover FC, Downes FP, et al. Infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the vanA resistance gene. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1342–1347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Li Y, Chen M. A plasmid-mediated SHV type extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in Beijing isolate of Enterobacter gergoviae. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao. 1994;34:106–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Murakami H, Kuwahara-Arai K, Hanaki H, Hiramatsu K. Contribution of a thickened cell wall and its glutamine nonamidated component to the vancomycin resistance expressed by Staphylococcus aureus Mu50. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2276–2285. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2276-2285.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta N. Drug resistance and R factors in the bowel bacteria of London patients before and after admission to hospital. Br Med J. 1969;2:407–411. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5654.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta N, Richmond MH. The purification and properties of a penicillinase whose synthesis is mediated by an R-factor in Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1966;98:204–209. doi: 10.1042/bj0980204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Neeling AJ, van den Broek MJ, Spalburg EC, Santen-Verheuvel MG, Dam-Deisz WD, Boshuizen HC, et al. High prevalence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in pigs. Vet Microbiol. 2007;122:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decousser JW, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Characterization of a chromosomally encoded extended-spectrum class A beta-lactamase from Kluyvera cryocrescens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3595–3598. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.12.3595-3598.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekema DJ, Pfaller MA, Schmitz FJ, Smayevsky J, Bell J, Jones RN, et al. Survey of infections due to Staphylococcus species: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific region for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997–1999. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32 Suppl 2:S114–S132. doi: 10.1086/320184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du B, Long Y, Liu H, Chen D, Liu D, Xu Y, et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection: risk factors and clinical outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:1718–1723. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1521-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth GJ, Lothian JL, Williams JD. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: report of an outbreak in a London teaching hospital. J Hosp Infect. 1988;11:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(88)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensor V, Warren R, O'Neill P, Butler V, Taylor J, Nye K, et al. Isolation of quinolone-resistance CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli from raw chicken meat sold in retail outlets in the West Midlands, UK. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13 Suppl 1:S274–S275. [Google Scholar]

- Ensor VM, Shahid M, Evans JT, Hawkey PM. Occurrence, prevalence and genetic environment of CTX-M {beta}-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae from Indian hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:1260–1263. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluit AC, Verhoef J, Schmitz FJ. Frequency of isolation and antimicrobial resistance of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria from patients in intensive care units of 25 European university hospitals participating in the European arm of the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program 1997–1998. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:617–625. doi: 10.1007/s100960100564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaze WH, Abdouslam N, Hawkey PM, Wellington EM. Incidence of class 1 integrons in a quaternary ammonium compound-polluted environment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1802–1807. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1802-1807.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkey P, Finch R. Tigecycline: in-vitro performance as a predictor of clinical efficacy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:354–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkey PM. The origins and molecular basis of antibiotic resistance. Br Med J. 1998;317:657–660. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7159.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henwood CJ, Livermore DM, Johnson AP, James D, Warner M, Gardiner A. Susceptibility of gram-positive cocci from 25 UK hospitals to antimicrobial agents including linezolid. The Linezolid Study Group. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:931–940. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.6.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J, M'Zali FH, Gascoyne-Binzi D, Hawkey PM. Evolution and spread of SHV extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in gram-negative bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;44:309–318. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert-Rogers LC, Heritage J, Todd N, Hawkey PM. Convergent evolution of TEM-26, a beta-lactamase with extended-spectrum activity. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33:707–720. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu K. The emergence of Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin in Japan. Am J Med. 1998;104:7S–10S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby GA, Medeiros AA, O'Brien TF, Pinto ME, Jiang H. Broad-spectrum, transmissible beta-lactamases. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:723–724. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809153191114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevons MP. ‘Celbenin'-resistant Staphylococci. Br Med J. 1961;1:124–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby WM. Extraction of a highly potent penicillin inactivator from penicillin resistant staphylococci. Science. 1944;99:454. doi: 10.1126/science.99.2579.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzis MD, Billot-Klein D, Goldstein FW, Williamson R, Tran VN, Carlet J, et al. Dissemination of the novel plasmid-mediated beta-lactamase CTX-1, which confers resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins, and its inhibition by beta-lactamase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:9–14. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knothe H, Shah P, Krcmery V, Antal M, Mitsuhashi S. Transferable resistance to cefotaxime, cefoxitin, cefamandole and cefuroxime in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Serratia marcescens. Infection. 1983;11:315–317. doi: 10.1007/BF01641355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey RW. Antibiotic resistance plasmids of Staphylococcus aureus and their clinical importance. Bacteriol Rev. 1975;39:1–32. doi: 10.1128/br.39.1.1-32.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartigue MF, Poirel L, Aubert D, Nordmann P. In vitro analysis of ISEcp1B-mediated mobilization of naturally occurring beta-lactamase gene blaCTX-M of Kluyvera ascorbata. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1282–1286. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1282-1286.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling TK, Xiong J, Yu Y, Lee CC, Ye H, Hawkey PM. Multicenter antimicrobial susceptibility survey of Gram-negative bacteria isolated from patients with community-acquired infections in the People's Republic of China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:374–378. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.1.374-378.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livermore DM, Yuan M. Antibiotic resistance and production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases amongst Klebsiella spp. from intensive care units in Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:409–424. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler A, Boag AK, Sung J, Lindsay JA, Guardabassi L, Dalsgaard A, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among staff and pets in a small animal referral hospital in the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:692–697. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltezou HC, Giamarellou H. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;27:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishaan AM, Mason EO, Jr, Martinez-Aguilar G, Hammerman W, Propst JJ, Lupski JR, et al. Emergence of a predominant clone of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus among children in Houston, Texas. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:201–206. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000151107.29132.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PC, Lindsay JA. Molecular characterisation of the dominant UK methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains, EMRSA-15 and EMRSA-16. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:516–521. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-6-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble WC, Virani Z, Cree RG. Co-transfer of vancomycin and other resistance genes from Enterococcus faecalis NCTC 12201 to Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;72:195–198. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90528-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel GJ. Clinical profile of ceftobiprole, a novel beta-lactam antibiotic. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13 Suppl 2:25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novais A, Canton R, Valverde A, Machado E, Galan JC, Peixe L, et al. Dissemination and persistence of blaCTX-M-9 are linked to class 1 integrons containing CR1 associated with defective transposon derivatives from Tn402 located in early antibiotic resistance plasmids of IncHI2, IncP1-alpha, and IncFI groups. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2741–2750. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00274-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MT. Staphylococci endemic in hospitals. Sci Basis Med Annu Rev. 1966. pp. 157–173. [PubMed]

- Paterson DL, Hujer KM, Hujer AM, Yeiser B, Bonomo MD, Rice LB, et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream isolates from seven countries: dominance and widespread prevalence of SHV- and CTX-M-type beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3554–3560. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.11.3554-3560.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippon A, Arlet G, Jacoby GA. Plasmid-determined AmpC-type beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1–11. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.1.1-11.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piddock LJ, Walters RN, Jin YF, Turner HL, Gascoyne-Binzi DM, Hawkey PM. Prevalence and mechanism of resistance to ‘third-generation' cephalosporins in clinically relevant isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from 43 hospitals in the UK, 1990–1991. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:177–187. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L, Kampfer P, Nordmann P. Chromosome-encoded Ambler class A beta-lactamase of Kluyvera georgiana, a probable progenitor of a subgroup of CTX-M extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:4038–4040. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.12.4038-4040.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L, Lartigue MF, Decousser JW, Nordmann P. ISEcp1B-mediated transposition of blaCTX-M in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:447–450. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.1.447-450.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolinson G. Forty years of beta-lactam research. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:589–603. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.6.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safo MK, Zhao Q, Ko TP, Musayev FN, Robinson H, Scarsdale N, et al. Crystal structures of the BlaI repressor from Staphylococcus aureus and its complex with DNA: insights into transcriptional regulation of the bla and mec operons. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1833–1844. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1833-1844.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szpirer C, Top E, Couturier M, Mergeay M. Retrotransfer or gene capture: a feature of conjugative plasmids, with ecological and evolutionary significance. Microbiology. 1999;145 Part 12:3321–3329. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-12-3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari HK, Sen MR. Emergence of vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) from a tertiary care hospital from northern part of India. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toleman MA, Bennett PM, Walsh TR. ISCR elements: novel gene-capturing systems of the 21st century. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:296–316. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00048-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsui Y, Yokota T. Role of an altered penicillin-binding protein in methicillin- and cephem-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:397–403. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.3.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron DE, Lindsay JA. Sau1: a novel lineage-specific type I restriction-modification system that blocks horizontal gene transfer into Staphylococcus aureus and between S. aureus isolates of different lineages. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5578–5585. doi: 10.1128/JB.00418-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh TR, Toleman MA, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Metallo-beta-lactamases: the quiet before the storm. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:306–325. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.306-325.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Lucien E, Hashimoto A, Pais GC, Nelson DM, Song Y, et al. Isothiazoloquinolones with enhanced antistaphylococcal activities against multidrug-resistant strains: effects of structural modifications at the 6-, 7-, and 8-positions. J Med Chem. 2007;50:199–210. doi: 10.1021/jm060844e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel LM, Clewell DB, Gill SR, Clark NC, McDougal LK, Flannagan SE, et al. Genetic analysis of a high-level vancomycin-resistant isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 2003;302:1569–1571. doi: 10.1126/science.1090956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte W, Strommenger B, Stanek C, Cuny C. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in humans and animals, Central Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:255–258. doi: 10.3201/eid1302.060924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]