Abstract

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest group of cell surface receptors. They are stimulated by a variety of stimuli and signal to different classes of effectors, including several types of ion channels and second messenger-generating enzymes. Recent technical advances, most importantly in the optical recording with energy transfer techniques––fluorescence and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer, FRET and BRET––, have permitted a detailed kinetic analysis of the individual steps of the signalling chain, ranging from ligand binding to the production of second messengers in intact cells. The transfer of information, which is initiated by ligand binding, triggers a signalling cascade that displays various rate-controlling steps at different levels. This review summarizes recent findings illustrating the speed and the complexity of this signalling system.

Keywords: G-protein-coupled receptors, G proteins, cyclic AMP, BRET, FRET

Introduction

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are a large family of cell surface receptors that transmit the signals of not only a multitude of transmitters and hormones but also of light, taste and smell (Pierce et al., 2002). They are characterized (a) by a common structure—a core comprising seven transmembrane α-helices with an extracellular amino and an intracellular carboxy terminus (Palczewski et al., 2000; Schertler, 2005)––, (b) by common signalling mechanisms (Marinissen and Gutkind, 2001), which result from the activation of heterotrimeric G proteins (Gαβγ) by catalysing the exchange of GDP for GTP in the G protein's α-subunit (Bourne et al., 1991) and (c) by multiple common regulatory and desensitization mechanisms (Collins et al., 1991; Lohse, 1993).

G-protein-coupled receptors are generally regarded as receptors that signal with intermediate speed. They can be contrasted on the one hand to the ion channel receptors—such as the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor––, which signal with millisecond speeds, and on the other hand to the slow enzymatic tyrosine kinase or guanylyl cyclase receptors, which elicit slow and prolonged intracellular signals that last over minutes to hours. This perception of the speed of GPCR-mediated signals is based mostly on physiological studies—such as increases in cardiac frequency in response to sympathetic stimulation of cardiac β-adrenoceptors—and classical biochemical assays generally performed on membrane preparations (Gilman, 1987; Bourne et al., 1991).

However, it appears that the potential of GPCRs to mediate rapid signals has often been underestimated. In fact, two well-studied examples showed already many years ago that GPCR-mediated signalling can be very fast. First, in the rhodopsin-mediated process of light perception, activation of the light receptor rhodopsin can be observed within 1 ms of light triggering (Makino et al., 2003), and even the downstream closure of the cGMP-gated cation channel—which requires the intermediate steps of transducin activation and cGMP hydrolysis by the transducin-activated phosphodiesterase—is observed within 200 ms (Makino et al., 2003). Second, electrophysiological recordings of GPCR-regulated channels, such as the opening of GIRK potassium channels by M2 muscarinic or by α2-adrenoceptors, show that an entire GPCR-signalling chain can be activated within 200–500 ms (Pfaffinger et al., 1985; Bünemann et al., 2001).

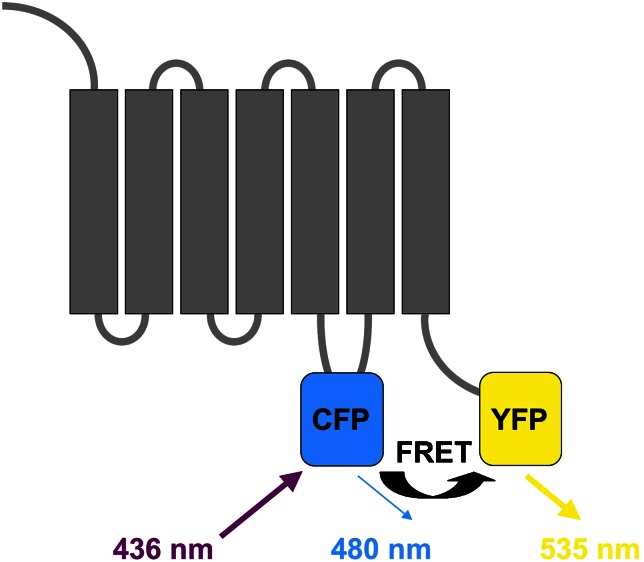

Although these earlier data convincingly demonstrate that GPCRs are capable of fast signalling, very little was known until recently about the kinetics of the individual steps involved in the triggering and transmission of signals via these receptors. The recent development of a number of fluorescent assays has now permitted the analysis of these steps in intact cells (Krasel et al., 2004). Such fluorescence-based assays were initially developed for purified, chemically labelled, reconstituted receptors (Gether et al., 1995). The use of cyan (CFP) and yellow (YFP) variants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) has later permitted the use of fluorescent techniques in intact cells by studying the transfer of energy from light-excited CFP to YFP (fluorescence resonance energy transfer, FRET; Förster 1948; Marullo and Bouvier, 2007). As FRET is very sensitive to the distance and the orientation of the two fluorophores, it can be used to detect both interactions between two different labelled proteins and conformational changes occurring in an individual protein carrying two labels. Figure 1 shows an example, where both CFP and YFP are placed in a single molecule (in this case a GPCR) to monitor intramolecular FRET and its alterations by conformational changes, which change the relative positions of CFP and YFP (see section Receptor activation for details). In a variant of this technique (Marullo and Bouvier, 2007), CFP is replaced by a light-emitting luciferase (bioluminescence resonance energy transfer, BRET); this results not only in reduced background signals but also in a decrease in sensitivity and, hence, temporal resolution. In another variant, YFP is replaced by the small fluorescein derivative FlAsH, which binds to short cysteine-containing sequences and permits the use of a label much smaller than GFPs (Hoffmann et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

Example of a G-protein-coupled receptor modified for fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) analysis of receptor activation (conformational change). A cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) is placed in the third intracellular loop and a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) at the C terminus. FRET occurs upon excitation of CFP (with light at 436 nm, causing emission at 480 nm), which allows energy transfer to YFP (provided that the latter is close enough, <10 nm distance), which results in emission at 535 nm. The ratio of 535 and 480 nm emissions is an indicator of FRET and is strongly influenced by the distance between CFP and YFP, serving as a kind of ‘molecular ruler'. It should be noted that emission of CFP and/or YFP can also be affected by other factors, such as pH or fluorescence quenching, which necessitates appropriate controls. In bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET), the donor CFP is replaced by the light-emitting enzyme luciferase. In a variant of FRET, the acceptor YFP is replaced by the small dye FlAsH, which binds to tetracysteine-containing motifs that can be engineered into the protein sequence.

The individual elements of a GPCR signalling cascade are very well characterized. The most important steps are (1) agonist binding, (2) receptor conformational change, (3) receptor–G-protein interaction, (4) G-protein conformational changes including GDP release and GTP binding, (5) G protein–effector interaction, (6) change in effector activity and (7) the resulting ion conductance or second messenger concentration changes. Information about the individual steps comes from a variety of techniques involving membrane preparations and biochemistry, intact cells and, finally, intact organs.

Steps in the GPCR signalling cascade

Agonist binding

Agonist binding to receptors is the step that initiates the signalling cascade. There is a wealth of data on the kinetics of agonist binding from radioligand binding to membranes and, less so, to intact cells or tissues. There are, however, two problems with the use of these systems: first, radiolabelled agonists can be used for radioligand binding only if they are of high affinity (that is, in the low nanomolar range) so that the agonist–receptor complex does not dissociate during the steps required to separate bound and free radioligand (such as filtration). And second, most assays have been done in membranes washed more or less free of GTP, which results in formation of a stable receptor–G-protein complex that has high affinity for agonists (in fact in many instances, it is only this high-affinity complex that can be detected with agonist radioligands). Whereas the on-rate of agonist binding appears to be generally diffusion-limited, and thus is directly dependent on the agonist concentration, the establishment of a steady state depends on both the on- and the off-rate and thus high-affinity radioligands tend to show long times to reach this steady state (reviewed by Weiland and Molinoff, 1981). An example of such data is the binding of the high-affinity agonist N6-phenylisopropyl adenosine to A1-adenosine receptors, which has an affinity of about 1 nM and occurs with a kon of 0.05 nM−1 min−1, reaching equilibrium in about 15 min (Lohse et al., 1984). These values are clearly much slower than physiological responses to low molecular weight agonists and indicate that classical agonist radioligand binding data reflect an unphysiological setting, and that the reported rate constants are not those that occur in vivo.

More recently, attempts have been made to monitor the agonist–receptor interaction with optical methods. This has been done by labelling the receptor and the agonist with fluorescent labels (of different but overlapping colour spectra), and studying FRET between the two labels, which results in an emission of the fluorophore with the longer emission wavelength (acceptor) when the fluorophore with the shorter emission wavelength (donor) is excited. FRET is exquisitely sensitive to changes in the distance of the two fluorophores (it decreases with the sixth power of the distance). This technique has been used to study agonist–receptor interactions for the neurokinin NK2 receptor and the parathyroid hormone (PTH) receptor. In the case of the small peptide neurokinin A and its NK2 receptors, the data suggest a simple bimolecular binding reaction with observed rate constants (depending on agonist concentrations) of 0.1–2 and 0.05 s−1, respectively (Palanche et al., 2001). It has been suggested that these two rate constants may reflect two distinct conformations of the receptor, the fast one linked to an intracellular Ca signal, the slower one correlating with intracellular cAMP accumulation, but perhaps also a desensitized state (Palanche et al., 2001). PTH is a large 81 amino-acid peptide ligand and is usually studied with an active analogue comprising the 34 amino-acid N terminus. Using this fluorescently labelled N terminus, a biphasic interaction with the PTH receptor was observed (Castro et al., 2005). A first rapid interaction (τ≈100 ms, strictly dependent on agonist concentration)—presumably between the large N terminus of the receptor and the C terminus of the ligand—was followed by a second, slower event (τ≈1 s), presumably representing the interaction of the ligand's N-terminal portion with the transmembrane core of the receptor. Taken together, these data suggest that agonist binding to GPCRs is quite rapid, with key events occurring in the sub-second range. However, it is interesting to note that in both types of receptors, biphasic agonist-binding kinetics has been observed, but both the rates and the respective interpretation vary.

Receptor activation

Agonist binding to receptors is intricately linked to a conformational change in the receptors that results in the (or an) active state—where ‘active' means the ability of the receptors to not only couple and signal to G proteins but also to be recognized by G-protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs), β-arrestins and the internalization machinery. The nature of this conformational change has been studied in great detail by a variety of biochemical, mutagenesis and spectroscopic techniques (Farrens et al., 1996; Sheik et al., 1996; Wieland et al., 1996; Gether, 2000). All these studies indicate that receptor activation leads to a relative rearrangement of the receptor's transmembrane helices, particularly of helices III and VI. However, a major question is whether receptors (such as rhodopsin) can adopt multiple active conformations or whether they switch simply between an OFF and an ON state as described in most classical models of receptor activation.

In view of the relative movements of helices III and VI, Kobilka and coworkers have searched for sites in β2-adrenoceptors that can be chemically labelled with fluorophores and result in conformationally sensitive receptor fluorescence due to fluorescence quenching. To this end, they created a receptor mutant where accessible cysteines had been removed by mutation, and cysteines were introduced at different sites to allow selective labelling of the purified receptors. These studies confirmed the concept of agonist-induced relative movements of helices III and VI. They further allowed the direct monitoring of conformational changes in a GPCR (Gether et al., 1995), which suggested the existence of intermediate states and sequential activation of receptors via these intermediate states (Swaminath et al., 2004, 2005; Yao et al., 2006). The agonist-induced fluorescence changes were relatively slow, suggesting that the purified reconstituted receptors did not show the same behaviour as receptors in their native environment. More recent studies indicate that careful reconstitution can partially restore the speed of the receptors' conformational switch and result in agonist-induced changes of intramolecular receptor fluorescence on the timescale of about 30 s (Yao et al., 2006).

A different strategy, used by our laboratory, involves again the use of FRET between fluorophores—generally CFP and YFP—attached to the receptor sequence. Placement of these labels in the third intracellular loop and the C terminus, respectively, led to the generation of receptor constructs with remarkably preserved ligand binding and, in many instances, also largely preserved signalling properties. If suitably constructed, these receptors react to agonists with a change, usually a reduction, in FRET between CFP and YFP. Such studies have been done with a number of receptors, including the α2A-adrenergic, β1-adrenergic, PTH- and A2A-adenosine receptors (Vilardaga et al., 2003, 2005; Hoffmann et al., 2005; Rochais et al., 2007). As an alternative to YFP, labelling of specific, cysteine-containing sequences introduced into a receptor sequence has been used to label sites in the third loop of receptors with the small fluorescein analogue termed FlAsH (for fluorescein arsenical hairpin binder; Hoffmann et al., 2005). Following the original description for the A2A-adenosine receptor (Hoffmann et al., 2005), similar labelling and FRET protocols using FlAsH and suitably mutated receptors were described for the α2A- and β1-adrenoceptors (Nikolaev et al., 2006b; Rochais et al., 2007).

The FRET signals observed in such receptor constructs in response to agonist binding decrease rapidly and in a mono-exponential manner, presumably reflecting the conformational change that results in the—or an—active conformation of the receptors (Vilardaga et al., 2003). The kinetics of these changes is much faster than previously thought. They depend both on the nature of the receptor and on the type of ligand. Receptor activation occurs with a rate constant τ of 30–50 ms in A2A-adenosine, the α2A- and β1-adrenoceptors (Vilardaga et al., 2003, 2005; Hoffmann et al., 2005; Rochais et al., 2007). Whereas these rate constants are faster than had been assumed so far, they are still considerably slower than those measured for rhodopsin, where the active, G-protein coupling metarhodopsin II form is generated within about 1 ms upon light activation (see Okada et al., 2001). Adding to the kinetic complexity is the example of the PTH receptor mentioned above, where activation occurs with a τ of ≈1 s (Vilardaga et al., 2003). This rate constant agrees very well with the second slower binding step to the receptor's transmembrane domain that is described above, suggesting that the second binding step coincides with receptor activation. Relatively slow activation kinetics has also been described for a similar bradykinin receptor construct (Chachisvilis et al., 2006). It remains to be seen whether the speed of activation of individual receptors is related to the type of endogenous ligand (for example, biogenic amines vs peptides and proteins), the class of receptor, the type of downstream signals or whether it just happens to be a property of an individual receptor.

Studies with the α2A-adrenoceptors have, furthermore, revealed that different types of ligands cause changes in FRET with very different speeds (Vilardaga et al., 2005; Nikolaev et al., 2006b). The conformational changes induced by partial agonists, which produce signals of only partial amplitude, are considerably slower than those induced by full agonists (Nikolaev et al., 2006b). Inverse agonist signals, which correspond to an increase in FRET in these receptor constructs, are even slower (Vilardaga et al., 2005). These observations are in line with the hypothesis that the different compounds may induce distinct conformations of the receptors—a finding in agreement with the mechanistic studies by Kobilka and coworkers referred to above––, and that they do so with distinct kinetics.

Receptor–G-protein interaction

The interaction of receptors with G proteins has been studied in numerous classical biochemical experiments, using for example high-affinity binding, GDP release from the G protein α-subunit or subsequent binding of GTP as read-outs (Gilman, 1987; Bourne et al., 1991). However, given the rapid speeds of receptor activation that were discussed above it is not surprising that faster, optical techniques are required to monitor these interactions at their true speed.

Receptor–G-protein interactions have recently been monitored both via FRET (Hein et al., 2005, 2006) and the related technique of BRET where the donor is a light-emitting luciferase instead of a fluorescent protein (Gales et al., 2005, 2006). In either case, one of the labels is located in the receptors (generally at the cytosolic C terminus), whereas the other is located in one of the three types of G-protein subunits (where different possible locations for a GFP insertion have been described for Gα, Gβ and Gγ). Both approaches, BRET and FRET, agree that the interaction between activated receptors and their G proteins can be very rapid, reaching—at high expression levels—rate constants in the 30–50 ms range (Hein et al., 2005, 2006) or below 300 ms (Gales et al., 2005). The faster times were observed by FRET, a technique that appears to be more suited for kinetic measurements as the higher emission intensities allow shorter recording intervals (Marullo and Bouvier, 2007). These rates suggest that the interactions between receptors and G proteins are as rapid as the activation of the receptors themselves, or—in other words—that activated receptors need virtually no time to find and interact with G proteins, provided that the latter are expressed at sufficiently high levels.

Thus, it would appear plausible to assume that receptors and G proteins must be located in close proximity or even be pre-coupled. However, the studies carried out to date do not agree on the extent of pre-coupling, that is, on receptors and G proteins coupled in the absence of agonist. Whereas Nobles et al. (2005) and Gales et al. (2005, 2006) found evidence with FRET/BRET for significant pre-coupling between α2-adrenoceptors and a G-protein complex consisting of Gαi1β1γ2, Hein et al. (2005) using FRET found no significant pre-coupling of the same receptors and G proteins. In view of similar methods, other receptors such as the β2-adrenoceptor have been implicated to form a complex with their cognate G protein by Gales et al. (2005). A major problem in these FRET/BRET-based studies is the accurate quantification of pre-coupling due to the lack of suitable negative and positive controls. Therefore, further studies need to rigorously address the issue of receptor–G-protein pre-coupling and its significance for signalling. This issue may be further complicated by the fact that, like any protein–protein interaction, receptors and G proteins must have some finite affinity even in their basal state, which will have to result in the existence of receptor–G-protein complexes if the expression level is sufficiently high. Thus, the issue of pre-coupling may in fact also be a question of terminology.

G-protein activation

The interaction of agonist-activated receptors with G proteins results in the activation of the G proteins, an activation that causes the G proteins to enter their ‘GTPase cycle' (Gilman, 1987; Bourne et al., 1991). This cycle involves a number of steps, most notably release of GDP from the Gα-subunit (resulting in the formation of a high-affinity ‘ternary' complex between the receptor with its agonist and the heterotrimeric G protein), binding of GTP to the Gα-subunit (causing the G protein to adopt its active state), coupling of the Gα- as well as the Gβγ-subunits to effectors (leading to activation or inhibition of these effectors) and finally termination of the active state of G proteins by the GTPase activity of the Gα-subunit (followed by resumption of the inactive state of the G proteins and, concomitantly, of the effectors). All these steps have been investigated in a plethora of settings for various ensembles of receptors, G proteins and effectors (see Gilman, 1987; Bourne et al., 1991 for classical examples), and even though these—mostly biochemical—assays have presumably underestimated the speeds of these steps in situ, it was clear from these early studies that such G-protein activation and signalling can be quite rapid.

Again, the use of FRET and BRET techniques has led to a re-appraisal of the kinetics of these signalling steps and to some extent also of the underlying mechanisms. As described above for the receptor–G-protein interaction, these studies involved the use of G proteins carrying labels in the Gα- and in either the Gβ- or the Gγ-subunit. These labels were used based on the classical assumption (Gilman, 1987; Bourne et al., 1991) that GTP binding and the resultant conformational change of the Gα-subunit result in dissociation of the G protein into the active, GTP-bound Gα-subunit and a Gβγ-complex (both of which can independently couple to downstream effectors). It was thus assumed that activation of such labelled G proteins would lead to their dissociation and, consequently, to a loss in FRET. Surprisingly, however, this was not always observed, and some constellations of labelled G proteins showed clear and rapid increases in FRET upon activation (Bünemann et al., 2003; Frank et al., 2005). Whereas the functionality of some of these constructs has been questioned (Gibson and Gilman, 2006), their ability to transmit a signal with appropriate kinetics suggests that they were at least capable of functional coupling to receptors and effectors. In view of these data, it appears that at least G proteins of the Gi type do not dissociate during activation, but rather undergo a conformational re-arrangement of the heterotrimer that allows the G-protein subunits to signal to effectors (Frank et al., 2005; Gales et al., 2006). A similar conclusion had been proposed earlier on the basis of the observation that a yeast G-protein construct with its α- and β-subunit homologues tethered together in a single fusion protein can signal without complete separation of the subunits (Klein et al., 2000). These data suggest that G proteins may signal while remaining in a heterotrimeric complex—even though, as in the case of pre-coupling discussed above, the notion of a complex may be in part a question of terminology. However, if indeed the subunits of an activated G protein stay close together, this might in fact solve several puzzling issues. For example, it might explain why the Gβγ-subunits of some G proteins can specifically couple to effectors (such as G-protein-activated inward-rectifying K+ channels, G-protein-activated inward-rectifying K+ channel (GIRK) channels), whereas others do not. Furthermore, it may explain how, following the termination of a signal, G proteins can correctly re-assemble, which would be difficult to imagine if G proteins fully dissociated and their subunits diffused freely at the cell surface (Quitterer and Lohse, 1999).

FRET was initially introduced for the study of G-protein activation in intact cells for Dictyostelium (Janetopoulos et al., 2001) and was later also used in other systems including yeast (Yi et al., 2003) and mammalian G proteins (Bünemann et al., 2003; Azpiazu and Gautam, 2004). The kinetics of the activation of G proteins by receptors monitored by FRET or BRET (Gales et al., 2006) appears to be rather slow. For example, while α2-adrenoceptor activation and its interaction with Gi occur with time constants of 30–50 ms (Hein et al., 2005), FRET signals indicate that Gi activation requires 0.5–1 s (Bünemann et al., 2003; Nikolaev et al., 2006b). Similarly, in the Gs-coupled β1-adrenergic and A2A-adenosine receptor systems, receptor activation and receptor–G-protein interaction occurred with time constants of about 50 ms, whereas Gs activation was about one order of magnitude slower, with a time constant of 450 ms (Hein et al., 2006). Biochemical experiments suggest that GDP release—which is the slowest step of the GTPase cycle in membrane-based assays—may be the reason for the delay between receptor–G-protein interaction and G-protein activation. Taken together, these data suggest that, compared with the upstream steps, G-protein activation is a rate-limiting step in the activation of these signalling pathways.

The deactivation of G proteins occurs via the GTPase activity of their Gα-subunit, which permits the re-establishment of the inactive G-protein heterotrimer (Bourne et al., 1991), a reaction that can be very significantly accelerated by the regulator of G-protein signalling proteins (Xie and Palmer, 2007). Deactivation of the G protein FRET or BRET signals follows a time course that is compatible with the slow GTPase activity of G proteins (Bünemann et al., 2003; Hein et al., 2005, 2006; Nikolaev et al., 2006b).

The general nature of the G-protein signals recorded with optical methods make them a very suitable tool to evaluate the activity of orphan receptors or to assess the activity of unknown compounds at a given receptor (Gales et al., 2006; Nikolaev et al., 2006b, 2007). It remains to be seen whether this may evolve into a generally applicable screening method.

Effector activation and second messenger signals

Activated G proteins couple to one (or more) effectors, such as adenylyl cyclases or ion channels, and modulate their activity. Ample evidence indicates that this coupling is specific, agonist dependent, and is terminated by the GTPase activity of the Gα-subunit of the G protein concerned. The simultaneous recording of Gi protein FRET signals by fluorescence recording and GIRK channel activity by whole-cell electrophysiological recordings (Bünemann et al., 2003) illustrate a very tight coupling between the active state of the G protein and the effector. The traces of both, the on-reaction and the off-reaction, were virtually superimposable.

Although this close coupling is evident for G proteins with ion channels, the situation is more complex for biochemical second messengers such as cAMP. The intracellular concentrations of cAMP have also been monitored in recent years by a number of FRET indicators (reviewed by Nikolaev and Lohse, 2006). Even though these sensors react to cAMP with different speeds—monomolecular sensors are faster than those composed of different subunits––, they all show that intracellular cAMP responses are relatively slow compared with the processes discussed so far. First, cAMP responses show a lag time of several seconds before they become apparent, and take many seconds up to several minutes to peak (Zaccolo et al., 2000; DiPilato et al., 2004; Nikolaev et al., 2004; Ponsioen et al., 2004). Second, the decay of the cAMP signals is even much slower and is largely determined by the activity of phosphodiesterases (Mongillo et al., 2004; Nikolaev et al., 2005).

cAMP levels can be imaged by FRET simultaneously with intracellular Ca2+ levels using Fura-2 (Landa et al., 2005; Harbeck et al., 2006; Willoughby and Cooper, 2006). These experiments have revealed complex interactions, mediated presumably via Ca2+-dependent adenylyl cyclases as well as phosphodiesterases, that result in either synchronous or antisynchronous oscillations of the two second messengers.

Furthermore, cAMP imaging studies have confirmed the notion (Rich et al., 2001; Fischmeister et al., 2006) that cAMP signalling in cells, in particular in cardiomyocytes, may be compartmentalized. Studies with cAMP imaging have reported discrete microdomains going in parallel with the striated pattern of cardiomyocytes (Zaccolo and Pozzan, 2002), different kinetics of submembrane and nuclear cAMP levels (DiPilato et al., 2004) and local cAMP responses to β2-adrenergic vs generalized cAMP responses to β1-adrenoceptor stimulation (Nikolaev et al., 2006a). These data illustrate that both the temporal and the spatial patterns of G-protein-mediated signalling can become very complex at the second messenger level.

GRK-mediated phosphorylation and β-arrestin binding

Both the phosphorylation of GPCRs by GRKs and the subsequent binding of β-arrestins terminate ‘classical' signalling and trigger receptor internalization and ‘non-classical' signalling such as stimulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. FRET-based assays have also been developed to monitor these steps, using fluorescently labelled receptors and β-arrestins (Vilardaga et al., 2003; Krasel et al., 2005; Violin et al., 2006). The conclusions from such kinetic experiments have been reviewed by Krasel et al. (2004) and will only briefly be summarized here.

First, it appears that GRK-dependent phosphorylation is the rate-limiting step in these experiments; this process is critically dependent on the level of GRK expression and may take several minutes for completion. Following receptor phosphorylation, the subsequent binding of β-arrestins is fairly rapid and may occur with rate constants in the order of a few seconds. This suggests that receptor phosphorylation is the slowest of all processes discussed here, and may serve as a ‘monitor' for overall activity of a receptor system. β-Arrestin binding may then closely follow GRK-mediated phosphorylation and, under these circumstances, be essentially dependent on a subsequent activation of receptors by agonist—a process that is, as described above, very rapid and may fine-tune the effects of the GRK/β-arrestin components of the signalling system.

Outlook

New techniques of optical recording using luminescence and fluorescence have opened up new venues of research into the signalling by G proteins and their receptors. These methods allow the detailed analysis of individual steps of signalling cascades, including their temporal and spatial patterns. Table 1 summarizes data that have been obtained for individual steps of the GPCR signalling cascade for different class A receptors. It illustrates that many rates still need to be determined. Furthermore, the differences between these receptors and the much faster rhodopsin on the one hand, and the apparently slower NK2 receptor (also class A) and PTH receptor (class B) cannot yet be attributed to specific reasons and require further research.

Table 1. Kinetics of various steps in the receptor/G-protein signalling chain as determined by FRET or BRET in intact cells.

| Step | Half-life t1/2 (ms) |

|---|---|

| Receptor conformational change | 30–50 |

| Receptor–G-protein interaction | 30–50 |

| G-protein activation | 300–500 |

| cAMP accumulation | 20 000–50 000 |

Abbreviations: BRET, bioluminescence resonance energy transfer; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer.

Values represent estimates of half-lifes (in milliseconds) for the individual steps at maximal speed (that is, high agonist concentrations and protein levels) for the β1-adrenoceptor/Gs/cAMP cascade. Similar values were determined for α2A-adrenoceptors with Gi/Go and for A2A-adenosine receptors with Gs. See text for references.

Even at this preliminary stage, such studies have revealed a number of interesting and provocative findings. They have identified rate-limiting steps in the signalling chains—such as the formation of an active G protein following the receptor–G-protein interaction, or the synthesis of cAMP in response to G-protein activation. Furthermore, these studies have revealed patterns of intracellular signalling that are more complex than previously anticipated, both in terms of temporal patterns—as exemplified by simultaneous oscillations of both intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP—and their spatial distribution—as revealed by locally confined areas of intracellular cAMP signalling. Deciphering the meaning and the physiological relevance of the complex information that appears to be contained in these signals will be a major task of future receptor and signalling research.

Acknowledgments

We have been supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), the Fonds of the Chemical Industry (FCI) and the Bayerische Forschungsstiftung.

Glossary

- BRET/FRET

bioluminescence/fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- CFP/GFP/YFP

cyan/green/yellow fluorescent protein

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Azpiazu I, Gautam N. A fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based sensor indicates that receptor access to a G protein is unrestricted in a living mammalian cell. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27709–27718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403712200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne HR, Sanders DA, McCormick F. The GTPase superfamily: conserved structure and molecular mechanism. Nature. 1991;349:117–127. doi: 10.1038/349117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bünemann M, Bücheler MM, Philipp M, Lohse MJ, Hein L. Activation and deactivation kinetics of α2A- and α2C-adrenergic receptor-activated G protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+-channel currents. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47512–47517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bünemann M, Frank M, Lohse MJ. Gi protein activation in intact cells involves subunit rearrangement rather than dissociation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:16077–16082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536719100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro M, Nikolaev VO, Palm D, Martin J, Lohse MJ, Vilardaga JP. Turn-on switch in parathyroid hormone receptor by a two-step PTH binding mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16084–16089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503942102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chachisvilis M, Zhang YL, Frangos JA. G protein-coupled receptors sense fluid shear stress in endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15463–15468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607224103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S, Lohse MJ, O'Dowd B, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Structure and regulation of G protein-coupled receptors: the β2-adrenergic receptor as a model. Vitam Horm. 1991;46:1–39. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPilato LM, Cheng X, Zhang J. Fluorescent indicators of cAMP and Epac activation reveal differential dynamics of cAMP signaling within discrete subcellular compartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16513–16518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405973101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrens DL, Altenbach C, Yang K, Hubbell WL, Khorana HG. Requirement of rigid body motion of transmembrane helices for light activation of rhodopsin. Science. 1996;274:768–770. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischmeister R, Castro LR, Abi-Gerges A, Rochais F, Jurevicius J, Leroy J, et al. Compartmentation of cyclic nucleotide signaling in the heart: the role of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Circ Res. 2006;99:816–828. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000246118.98832.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster T. Zwischenmolekulare Energiewanderung und Fluoreszenz. Ann Physik. 1948;2:55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Frank M, Thümer L, Lohse MJ, Bünemann M. G-protein-activation without subunit dissociation depends on a Gαi-specific region. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24584–24590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gales C, Rebois RV, Hogue M, Trieu P, Breit A, Hebert TE, et al. Real-time monitoring of receptor and G-protein interactions in living cells. Nat Methods. 2005;2:177–184. doi: 10.1038/nmeth743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gales C, Van Durm JJ, Schaak S, Pontier S, Percherancier Y, Audet M, et al. Probing the activation-promoted structural rearrangements in preassembled receptor–G protein complexes. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:778–786. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gether U. Uncovering molecular mechanism involved in activation of G protein-coupled receptor. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:90–113. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gether U, Lin SB, Kobilka BK. Fluorescent labeling of purified β2-adrenergic receptor: evidence for ligand-specific conformational changes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28268–28275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.28268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson SK, Gilman AG. Giα and Gβ subunits both define selectivity of G protein activation by α2-adrenergic receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:212–217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509763102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman AG. G-proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Ann Rev Biochem. 1987;56:615–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbeck MC, Chepurny O, Nikolaev VO, Lohse MJ, Holz GG, Roe MW. Simultaneous optical measurements of cytosolic Ca2++ and cAMP in single cells. Sci STKE. 2006;353:l6. doi: 10.1126/stke.3532006pl6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein P, Frank M, Hoffmann C, Lohse MJ, Bünemann M. Dynamics of receptor/G protein coupling in living cells. EMBO J. 2005;24:4106–4114. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein P, Rochais F, Hoffmann C, Dorsch S, Nikolaev VO, Engelhardt S, et al. Gs activation is time-limiting in initiating receptor-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33345–33351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann C, Gaietta G, Bünemann M, Adams S, Oberdorff-Maass S, Behr B, et al. A FLASH-based approach to determine G protein-coupled receptor activation in living cells. Nat Methods. 2005;2:171–176. doi: 10.1038/nmeth742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janetopoulos C, Jin T, Devreotes P. Receptor-mediated activation of heterotrimeric G-proteins in living cells. Science. 2001;291:2408–2411. doi: 10.1126/science.1055835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Reuveni H, Levitzki A. Signal transduction by a nondissociable heterotrimeric yeast G protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3219–3223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050015797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasel C, Bünemann M, Lorenz K, Lohse MJ. Arrestin binding to the β2-adrenergic receptor requires both receptor phosphorylation and receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9528–9535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasel C, Vilardaga JP, Bünemann M, Lohse MJ. Kinetics of G-protein-coupled receptor signalling and desensitization. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:1029–1031. doi: 10.1042/BST0321029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa LR, Jr, Harbeck M, Kaihara K, Chepurny O, Kitiphongspattana K, Graf O, et al. Interplay of Ca2+ and cAMP signaling in the insulin-secreting MIN6 beta-cell line. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31294–31302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505657200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse MJ. Molecular mechanisms of membrane receptor desensitization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1179:171–188. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90139-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse MJ, Lenschow V, Schwabe U. Two affinity states of Ri adenosine receptors in brain membranes: analysis of guanine nucleotide and temperature effects on radioligand binding. Mol Pharmacol. 1984;26:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino CL, Wen XH, Lem J. Piecing together the timetable for visual transduction with transgenic animals. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:404–412. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinissen MJ, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and signaling networks: emerging paradigms. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:368–376. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01678-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marullo S, Bouvier M. Resonance energy transfer approaches in molecular pharmacology and beyond. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:362–365. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongillo M, Evellin S, Lissandron V, Terrin A, Hannawacker A, Lohse MJ, et al. FRET-based analysis of cAMP dynamics in live cells reveals distinct functions of compartmentalized phosphodiesterases in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2004;95:67–75. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000134629.84732.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev VO, Boettcher C, Dees C, Bünemann M, Lohse MJ, Zenk MH. Live-cell monitoring of μ-opioid receptor mediated G-protein activation reveals strong biological activity of close morphine biosynthetic precursors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27126–27132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev VO, Bünemann M, Hein L, Hannawacker A, Lohse MJ. Novel single chain cAMP sensors for receptor-induced signal propagation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37215–37218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400302200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev VO, Bünemann M, Schmitteckert E, Lohse MJ, Engelhardt S. Cyclic AMP imaging in adult cardiac myocytes reveals far-reaching β1-adrenergic but locally confined β2-adrenergic receptor-mediated signaling. Circ Res. 2006a;99:1084–1091. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250046.69918.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev VO, Gambaryan S, Engelhardt S, Walter U, Lohse MJ. Real-time monitoring of the PDE2 activity of live cells: hormone-stimulated cAMP hydrolysis is faster than hormone-stimulated cAMP synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1716–1719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev VO, Hoffmann C, Bünemann M, Lohse MJ, Vilardaga JP. Molecular basis of partial agonism at the neurotransmitter α2A-adrenergic receptor and Gi-protein heterotrimer. J Biol Chem. 2006b;281:24506–24511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev VO, Lohse MJ. Monitoring of cAMP synthesis and degradation in living cells. Physiology. 2006;21:86–92. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00057.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobles M, Benians A, Tinker A. Heterotrimeric G proteins pre-couple with G protein-coupled receptors in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18706–18711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504778102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Ernst OP, Palczewski K, Hofmann KP. Activation of rhodopsin: new insights from structural and biochemical studies. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:318–324. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanche T, Ilien B, Zoffmann S, Reck M-P, Bucher B, Edelstein SJ, et al. The neurokinin A receptor activates calcium and cAMP responses through distinct conformational states. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34853–34861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: a G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffinger PJ, Martin JM, Hunter DD, Nathanson NM, Hille B. GTP-binding proteins couple cardiac muscarinic receptors to a K channel. Nature. 1985;317:536–538. doi: 10.1038/317536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponsioen B, Zhao J, Riedl J, Zwartkruis F, van der Krogt G, Zaccolo M, et al. Detecting cAMP-induced Epac activation by fluorescence resonance energy transfer: Epac as a novel cAMP indicator. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:1176–1180. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quitterer U, Lohse MJ. Crosstalk between Gαi and Gαq-coupled receptors is mediated via Gβγ exchange. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10626–10631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich TC, Fagan KA, Tse TE, Schaack J, Cooper DM, Karpen JW. A uniform extracellular stimulus triggers distinct cAMP signals in different compartments of a simple cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13049–13054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221381398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochais F, Vilardaga JP, Nikolaev VO, Bünemann M, Lohse MJ, Engelhardt S. Real-time optical recording of β1-adrenergic receptor activation reveals supersensitivity of the Arg389 variant to carvedilol. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:229–235. doi: 10.1172/JCI30012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schertler GF. Structure of rhodopsin and the metarhodopsin I photointermediate. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheik SP, Zvyaga TA, Lichtarge O, Sakmar TO, Bourne HR. Rhodopsin activation blocked by metal-ion-binding sites linking transmembrane helices C and F. Nature. 1996;383:347–350. doi: 10.1038/383347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminath G, Deupi X, Lee TW, Zhu W, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, et al. Probing the β2-adrenoceptor binding site with catechol reveals differences in binding and activation by agonists and partial agonists. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22165–22171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminath G, Xiang Y, Lee TW, Steenhuis J, Parnot C, Kobilka BK. Sequential binding of agonists to the β2-adrenoceptor. Kinetic evidence for intermediate conformational states. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:686–691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilardaga JP, Bünemann M, Krasel C, Castro M, Lohse MJ. Measurement of the millisecond activation switch of G-protein-coupled receptors in living cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:807–812. doi: 10.1038/nbt838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilardaga JP, Steinmeyer R, Harms GS, Lohse MJ. Molecular basis of inverse agonism in a G protein-coupled receptor. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:25–28. doi: 10.1038/nchembio705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violin JD, Ren XR, Lefkowitz RJ. G-protein-coupled receptor kinase specificity for β-arrestin recruitment to the β2-adrenergic receptor revealed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20577–20588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiland GA, Molinoff PB. Quantitative analysis of drug–receptor interactions: I. determination of kinetic and equilibrium properties. Life Sci. 1981;29:313–330. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland K, Zuurmond HM, Andexinger S, Ijzerman AP, Lohse MJ. Stereo-specificity of agonist binding to β2-adrenergic receptors involves Asn-293. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9276–9281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby D, Cooper DM. Ca2+ stimulation of adenylyl cyclase generates dynamic oscillations in cyclic AMP. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:828–836. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie GX, Palmer PP. How regulators of G protein signaling achieve selective regulation. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:349–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao K, Parnot C, Deupi X, Ratnala VRP, Swaminath G, Farrens D, et al. Coupling ligand structure to specific conformational switches in the β2-adrenoceptor. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:417–422. doi: 10.1038/nchembio801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi TM, Kitano H, Simon MI. A quantitative characterization of the yeast heterotrimeric G protein cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10764–10769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834247100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaccolo M, De Giorgi F, Cho CY, Feng L, Knapp T, Negulescu PA, et al. A genetically encoded, fluorescent indicator for cyclic AMP in living cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:25–29. doi: 10.1038/71345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaccolo M, Pozzan T. Discrete microdomains with high concentration of cAMP in stimulated rat neonatal cardiac myocytes. Science. 2002;295:1711–1715. doi: 10.1126/science.1069982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]