Abstract

Specification of cardiac primordia and formation of the Drosophila heart tube is highly reminiscent of the early steps of vertebrate heart development. We previously reported that the final morphogenesis of the Drosophila heart involves a group of nonmesodermal cells called heart-anchoring cells and a pair of derived from the pharyngeal mesoderm cardiac outflow muscles. Like the vertebrate cardiac neural crest cells, heart-anchoring cells migrate, interact with the tip of the heart, and participate in shaping the cardiac outflow tract. To better understand this process, we performed an in-depth analysis of how the Drosophila outflow tract is formed. We found that the most anterior cardioblasts that form a central outflow tract component, the funnel-shaped heart tip, do not originate from the cardiac primordium. They are initially associated with the pharyngeal cardiac outflow muscles and join the anterior aorta during outflow tract assembly. The particular morphology of the heart tip is disrupted in embryos in which heart-anchoring cells were ablated, revealing their critical role in outflow tract morphogenesis. We also demonstrate that Slit and Robo are required for directed movements of heart-anchoring cells toward the heart tip and that the cell–cell contact between the heart-anchoring cells and the ladybird-expressing cardioblasts is critically dependent on DE-cadherin Shotgun. Our observations suggest that the similarities between Drosophila and vertebrate cardiogenesis extend beyond the early developmental events.

Keywords: heart, shotgun, slit

Morphologically, the simple tubular heart of Drosophila differs from the highly organized vertebrate heart. However, the specification of cardiac primordia in both Drosophila and vertebrate embryos is under the control of conserved genes encoding Nkx2.5/Tinman, GATA/Pannier, T-box/Dorsocross/Mid/H15, Mef2, and Hand families of transcription factors (1). The common genetic control mechanisms underlying the early steps of heart development are consistent with the fact that the vertebrate heart, like in Drosophila, initially forms from migrating bilateral primordia, which fuse and give rise to a linear heart tube (2). These similarities suggested that Drosophila may serve as a model system for studying the early steps of vertebrate heart development. A broad amount of data has been generated based on this assumption, revealing that although structurally simple, the Drosophila heart is composed of discrete subsets of cardioblasts and pericardial cells, making it more complex than previously thought (3–5). Both cell types can be subdivided into subpopulations expressing a cell subset-specific combinatorial code of transcription factors (6–13). Such a subdivision suggests that different subsets of cardiac cells differentiate into functionally distinct heart components—a possibility that is supported by the finding that the Svp/Doc-positive pair of cardioblasts has the capacity to develop into the inflow tract (ostial) cells (9, 14), whereas the four Tin-expressing cardioblasts adopt a cell fate of “working myocardium” (15).

Interestingly, in addition to the diversification of cardioblasts and pericardial cells within the segments, the entire heart organ undergoes morphogenetic changes along the anterior–posterior (A–P) axis. The A–P patterning of the heart underlies the functional subdivision of the cardiac tube into the heart proper (A8 to mid-A5) and the anterior part named the aorta (mid-A5 to T2) and is controlled by Hox genes, which are regionally expressed within the cardiac tube in nonoverlapping domains (16–19). The posteriorly located cardioblasts expressing Abdominal A (AbdA) give rise to the morphologically enlarged proper heart, whereas those expressing Ultrabithorax (Ubx) adopt a distinct morphological and functional identity specific for the aorta. Following the same rule, among the Svp/Doc cardioblasts, only those expressing AbdA in the posterior part of the cardiac tube will develop into the ostiae and form the inflow tract for the hemolymph. Interestingly, the most anterior part of the Drosophila heart also undergoes specific morphogenesis to form a funnel-shaped outflow tract (OFT) (20). The particular shape of the cardiac OFT depends on interactions among the heart-anchoring cells (HANC), the tip of aorta, and a pair of associated cardiac outflow muscles (COM) (20). The pair of COM muscles grows out from the pharyngeal mesoderm and attaches dorsally to the HANC cells and to the most anterior pair of Ladybird (Lb)-expressing cardioblasts in the aorta, thus ensuring a ventral bending of the heart tip. The HANC cells originate from the dorsal head epidermis and migrate toward the heart as a leading edge of an epithelial fold named the dorsal pouch. Interestingly, it has been shown that the vertebrate heart develops from two distinct myocardial precursor cells derived from (i) trunk mesoderm and (ii) pharyngeal mesoderm (secondary heart field). The formation of the cardiac OFT depends on cells derived from the pharyngeal mesoderm (21) and also involves a subpopulation of migrating nonmesodermal neural crest cells expressing Lb/Lbx1 (22–23). Thus, the identification of COM muscles originating from the pharyngeal mesoderm and the epidermally derived Lb-expressing HANC cells as components of the Drosophila cardiac OFT suggests an additional similarity between the Drosophila heart and the vertebrate heart.

Prompted by this similarity, we attempted to better understand the roles of different OFT components and the mechanisms that control the assembly of the OFT. We found that the most anterior cardioblasts (ACBs) are initially associated with COM muscles, suggesting that, like COMs, they arise from the pharyngeal mesoderm. During OFT assembly, ACBs form a key OFT component, the funnel-shaped tip of the heart. Thus, COMs not only contribute to the positioning of the heart tip but also ensure the direct link of ACBs with the heart tube. The final OFT morphogenesis also critically depends on HANC cells and is compromised after targeted HANCs ablation.

To gain insights into signals governing OFT assembly, we first focused on the Slit-Robo signaling pathway, which has been shown to be involved in neural crest cell migration in vertebrates (24–25), in Drosophila heart morphogenesis (26–28), and in the attraction of muscles to their attachment sites (29). We also tested the expression and function of DE-cadherin Shotgun (Shg), which is known to play important functions in the morphogenesis of the cardiac tube (30).

We found that Slit, Robo, and Shg play instrumental roles in the assembly of the OFT. In shg, slit, and double robo/robo2 mutant embryos, HANC cells migration is delayed or disrupted, and COM muscles do not attach to the heart tip.

Results and Discussion

The Most Anterior, OFT-Forming Cardioblasts Do Not Originate from Cardiac Primordium.

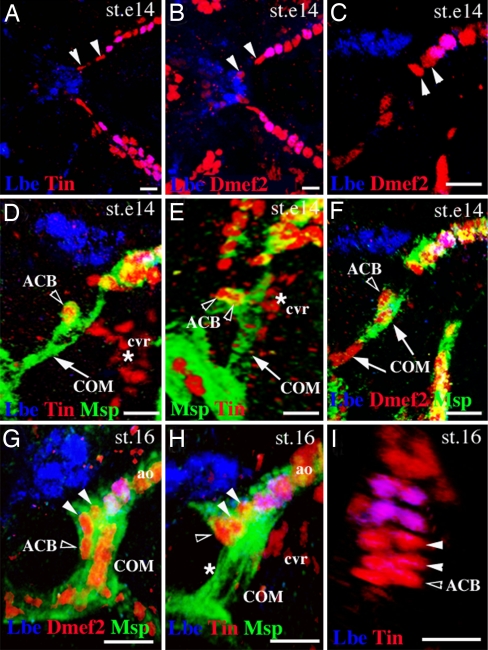

Our previous analyses (20) had revealed that the proper patterning of the OFT in Drosophila requires interactions between HANC cells and the Lb-expressing cardioblasts in the tip of the aorta. The establishment of this contact is facilitated by a pair of COM muscles that extend filopodia and attach from the ventral side to both the HANCs and to the pair of Lb-positive cardioblasts. Consequently, the final morphogenesis of the OFT depends on coordinated cell–cell interactions among the heart tip, migrating HANCs, and the dorsally growing COMs [see 3D OFT views in supporting information (SI) Movie 1]. During the OFT assembly, the most anterior cardioblasts undergo important morphological changes to form a funnel-shaped tip of the cardiac tube. To better characterize this process, we decided to follow the OFT-forming cardioblasts during development. We first examined the number of cardioblasts that precede the most anterior pair of Lb-expressing cardioblasts in early stage-14 embryos before the COM muscles contact the tip of the heart. The dorsal (Fig. 1 A and B) and lateral (Fig. 1C) views showed that at early stage 14 in the aorta, two pairs of Dmef2/Tin-positive cardioblasts (arrowheads in Fig. 1 A–C) lie anteriorly to Lb-positive cells. Unexpectedly, in the same stage embryos stained for Tin, two additional Tin-expressing cells are associated with COMs (open arrowheads in Fig. 1 D and E and SI Movie 2). In contrast to described (37) Tin-positive cvr cells that represent a rudiment of head aorta and lie ventrally to the OFT (asterisk in Fig. 1 D and E), the COM-associated Tin-positive cells also express Dmef2 (Fig. 1F) and a spectrin superfamily member Msp300 (Fig. 1 D–F) known to be expressed in somatic, visceral and heart embryonic muscles (35). Because of similarities to the Tin-expressing cardioblasts from cardiac primordium, we named them the anterior cardioblasts (ACBs). At the beginning of stage 16, ACBs are already connected with the tip of the heart (open arrowhead in Fig. 1G), and slightly later, they are no longer seen associated dorsally with the medial part of COMs (asterisk in Fig. 1H) but appear as an additional pair of cardioblasts preceding Lb-positive cells (Fig. 1I, open arrowhead, and SI Movie 3). They extend between the ventral side of HANC cells and the dorsal extremity of COM muscles (Fig. 1H, open arrowhead) and adopt OFT-specific triangular shapes. Despite their distinct morphology, ACBs express canonical cardioblast markers such as Dmef2 and Tin and are Zfh1-negative (data not shown). Because the ACBs are initially associated with pharyngeal COM muscles, they most probably originate from the pharyngeal mesoderm. This indicates an additional similarity between Drosophila and vertebrate OFT morphogenesis revealing that the main components of the Drosophila OFT are of pharyngeal (COMs, ACBs) and epidermal (HANCs) origin. Moreover, COM muscles not only contribute to the cardiac outflow positioning, as shown (20), but also serve as a scaffold for the ACBs, which associate with cardiac primordium and form a funnel-shaped OFT.

Fig. 1.

Cells associated with COM contribute to heart morphogenesis. (A–C) Dorsal (A and B) and lateral (C) OFT views from early stage-14 embryos stained with Tin and Lbe (A) or Dmef2 and Lbe (B and C). Arrowheads indicate two cardioblasts located anteriorly to the first Lbe-positive cardioblasts within the heart. (D and E) Lateral (D) and frontal (E) OFT view from early stage-14 embryo revealing COM muscles (arrow). Open arrowheads point to the ACBs. The cvr cells are located ventrally to the heart (asterisks). (F) Lateral OFT view from stage-14 embryo. Open arrowhead marks one of the two ACBs. Arrows point to the COM nuclei. (G and H) Lateral OFT views from stage-16 embryos. The ACBs (open arrowheads) are seen anteriorly to the two Dmef2-positive cardioblasts (filled arrowheads). (H) The ACBs initially associated with COM are no longer observed at this position (asterisk). (I) The most anterior aorta cells from a stage-16 embryo. Three pairs of Tin-expressing cardioblasts are located anteriorly to the first pair of Lbe-positive cardioblasts (open arrowhead indicates the ACBs). cvr, cephalic vascular rudiment; ao, aorta. (Scale bars: 10 μm.)

HANC Cells Are Required for Shaping the Cardiac OFT.

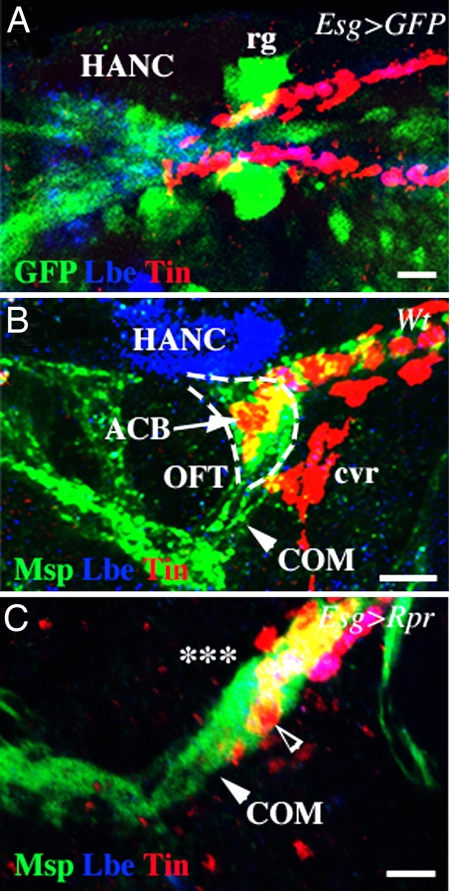

The direct contact of ACBs with HANC cells suggests they may play a role in shaping OFT. To investigate the function of HANC cells in OFT morphogenesis, we attempted to ablate them using a reaper (rpr)-mediated induction of apoptosis. We used Esg-GAL4 driver to target rpr expression to HANC cells. Because Esg-GAL4 in addition to HANCs is also expressed in ring glands (Fig. 2A), we, in parallel, used a ring gland-specific driver P0206-GAL4 to induce apoptosis in ring glands only (SI Fig. 6). In wild-type embryos, at stage 16, the funnel-shaped OFT extending between COMs and HANCs can be revealed by anti-Msp300 staining (Fig. 2B). The ACBs form cytoplasmic extensions dorsally underlying the HANC cells and ventrally aligned with the COM muscles (Fig. 2B and SI Movie 1). This cardiac OFT architecture is compromised in Esg-GAL4;UAS-Rpr embryos lacking the HANC cells (Fig. 2C). The heart tip appears disorganized, and the ACBs are displaced and are no longer seen dorsally to COMs (Fig. 2C). Moreover, the COM muscles attach to the Lb-positive cardioblasts in front and not from the ventral side. These defects are not seen in P0206-GAL4;UAS-Rpr embryos, in which only the ring glands were ablated (SI Fig. 6B). Thus, the altered COM attachments to the heart tip and a disrupted cardiac OFT morphology result from loss of HANC cells, revealing a pivotal role for HANCs in modeling the tip of the heart.

Fig. 2.

HANC cells are required for the OFT morphogenesis. (A) Dorsal OFT view from Esg-GAL4;UAS-nlsGFP stage-14 embryo showing expression of this effector line in the HANC cells. HANCs are revealed by Lbe staining, and the heart cells are stained for Tin. (B) Lateral OFT view from the wild-type stage-16 embryo. The heart and the HANCs are stained as above. Msp300 staining reveals COM muscles (arrowhead) and cardiac cells. Dashed line highlights the funnel shape of the OFT. (C) A similar view of a stage-16 embryo in which HANCs were ablated (asterisks) by targeted induction of apoptosis in the HANCs. Notice that the funnel-shaped OFT structure is absent. The most anterior heart cells (open arrowhead) most probably correspond to abnormally shaped ACBs. rg, ring gland. (Scale bars: 10 μm.)

Slit, Robo, and Shg Expression During OFT Morphogenesis.

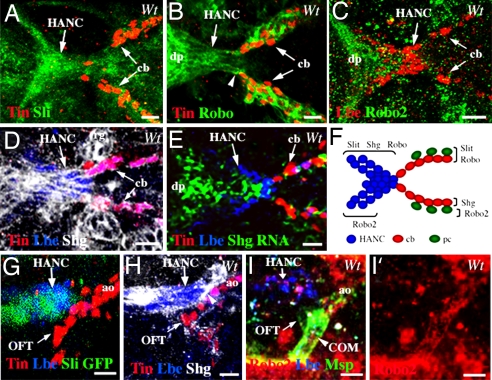

The precise spatial positioning of the OFT components originating from the distinct tissue primordia raises the question of how their assembly is controlled. We reasoned that the Slit-Robo signaling pathway that had been found to play a critical role in cardiac primordia assembly (26–28) and in the attraction of somatic muscle fibers to their tendonous attachment sites (29) is a good candidate for controlling the OFT morphogenesis. We also inferred from the previous work (30) that the DE-cadherin Shg that is expressed in the heart and involved in cardiac lumen formation may also control interactions between the HANC cells and the anterior cardioblasts. We first attempted to determine whether the candidate molecules are expressed in migrating HANC cells and the anterior heart tube. It has been shown that Slit is expressed in cardioblasts and in pericardial cells during embryonic stages 14 and 15 along the entire cardiac primordium (26–28). Slit expression was also observed in the head region in cells that form the invaginating dorsal pouch (38). We observed a high level of Slit expression in HANC cells at the time they come into contact with cardioblasts (Fig. 3 A and F). Interestingly, expression of the Slit receptor Robo is also seen in migrating HANCs (Fig. 3 B and F). In addition, Robo is particularly prominent in the dorsal pouch cells just anterior to HANCs (Fig. 3B) in which a low level of Robo2 is also observed (Fig. 3 C and F). In a similar manner to Slit and Robo, Shg is expressed in migrating HANC cells at stage 14 (Fig. 3 D–F). Shg protein can be seen in membranes of the entire cluster of HANCs (Fig. 3D), suggesting that it plays a role in keeping them associated. Shg can also be detected in membranes of cardioblasts and in the ring glands (Fig. 3D), as described (30). Using the Slit-GAL4;UAS-GFP line, we were also able to detect Slit expression in HANCs at stage 16 after OFT assembly (Fig. 3G). At this time point, the Shg accumulates between HANCs and the most anterior pair of Lb-positive cardioblasts (Fig. 3H and SI Movie 4) at the exact site of the initial contact between the heart tip and the HANC cells. This accumulation suggests the formation of adherent junctions between the Lb-expressing cardiac and HANC cells. The finding that HANC cells express Shg prompted us to take a closer look at living Shg-GFP embryos (33) and follow the invaginating cells in time-lapse experiments. We observed the invagination of the dorsal pouch and the migration of HANC cells associated with a coordinated posterior-to-anterior movement of the dorsal head epithelium (SI Movie 5).

Fig. 3.

Slit, Robo, Robo2, and Shg are dynamically expressed during assembly of the OFT. (A–E) The dorsal views of the OFT region from stage-14 embryos, arrows point to HANC cells and the most anterior cardioblasts. (A and B) Slit (A) and Robo (B) are expressed in migrating HANCs. (C) Robo2 is seen in dorsal pouch (dp) and in a subset of HANCs (arrowhead). (D and E) Shg protein (D) and shg RNA (E) are detected in the HANCs and in the cardioblasts. (F) Summary of Slit, Robo, Robo2, and Shg expression. (G–I′) The lateral OFT views from stage-16 embryos. (G) The Slit-GAL4-driven GFP confirms prominent Slit expression in HANC cells. (H) Shg accumulates at the contact between HANCs and the most anterior Lbe-expressing cardioblasts (arrowhead). (I and I′) Robo2 protein is expressed in COM muscles (arrowheads). Robo2 is also detected in the developing brain (a high red signal in I and I′). cb, cardioblasts. (Scale bars: 10 μm.)

As discussed previously, proper assembly of the OFT also requires a pair of COM muscles derived from the pharyngeal mesoderm. These muscles attach to the Lb-positive cardioblasts and to the HANC cells, which were both found to express Slit. Thus, we questioned whether the extremities of the COMs, like other somatic muscles, express Robo receptors and use Slit-Robo signaling for attraction. At stage 14, we were unable to detect Robo or Robo2 in growing COMs, most probably because their extremities are initially very narrow. However, slightly later, at stage 16, Robo2 protein was apparent within the COM muscles with a highest level at their attachment site (Fig. 3 I and I′) suggesting that Robo2 may drive the Slit-mediated attraction of COM muscles.

Slit, Robo, and Shg Control HANC Cell Motility and Assembly of the OFT.

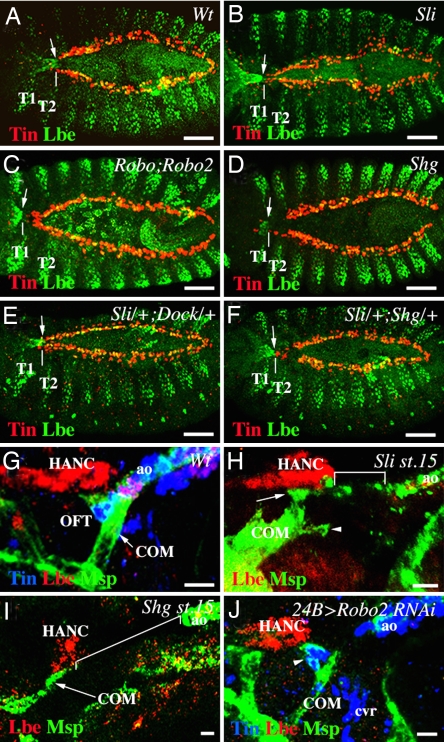

Based on the observation that slit, robo, and shg are expressed in both cardiac cells and migrating HANC cells, we questioned whether loss of function of these genes would affect HANC cell movement and contact with cardioblasts. When observed from the dorsal side, the normal position of HANC cells entering into the contact with cardioblasts in wild-type stage-14 embryos was at the thoracic segment T2 (Fig. 4A). Compared with the wild type, in age-matched slit (Fig. 4B) and in double robo mutant embryos (Fig. 4C), the position of HANC cells was much more anterior (at the thoracic segment T1), strongly suggesting that the rate of migration had been affected. Statistically, delayed HANC cell migration appear in ≈87% of slit and 70% of double robo mutant embryos (Table 1), indicating that slit and robo are both required but not sufficient to drive HANC movements. Moreover, among the two Robo receptors, loss of robo2 induces more penetrant migration phenotypes than loss of robo (Table 1), indicating that COMs, expressing robo2, play an active role in the OFT assembly. To test whether Robo receptors are involved in slit-induced HANC migration phenotypes, we analyzed transheterozygous mutant embryos. It turned out that robo and robo2 contribute to the slit phenotypes (Table 1) whereas dock, which is known to act as an intracellular component of Slit-Robo-dependent repulsion (39), seems to have a minor role in HANC cell positioning (Fig. 4E and Table 1). Abnormal HANC cell positioning and the disruption of the contact with the heart tip is also apparent in shg mutants (Fig. 4D and Table 1), revealing that Shg plays an instrumental role in HANC motility and in the OFT assembly. It has been demonstrated (26) that slit can interact with shg and trigger adhesive properties of cells. Therefore, we analyzed double-heterozygous sli/+;shg/+ embryos. Our data (Fig. 4F and Table 1) suggest that slit acts together with shg and contributes to the adhesive properties of HANC cells and thus to the proper patterning of the OFT. The fact that Shg is a part of β-catenin-dependent pathway linking cell adhesion with the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton (40) provides a way by which Slit-Robo can control the adhesive properties of cells and their motility. To test in which cells slit and shg are required during OFT assembly, we crossed the heart (Tin-GAL4) and the HANC (Esg-GAL4) drivers with UAS-RNAi lines targeting slit and shg. We found that either cardiac- or HANC-specific attenuation of both genes (Table 1) can affect HANC cell migration, strongly suggesting that slit and shg function is required in both cell types. On the other hand, a pair of COM muscles, which attach to the HANC cells and to the most anterior Lb-positive cardioblasts in the aorta (20), could also influence HANC cell positioning. To address this issue, we examined the attachment of COM muscles in slit mutant embryos in which HANCs migration is affected. As shown in Fig. 4H, in slit mutant embryos, COMs are not associated with the heart tip, even if some myopodia are projected in the right direction (arrowhead in Fig. 4H). Thus, one possibility is that COMs are attracted to the heart tip via Slit-Robo signaling and that inability of COMs to interact with the heart tip in a slit mutant background contributes to the slowdown in HANC cell movements. The potential role of Slit in COM attraction is in agreement with expression of Slit in the cardioblasts (26–28) and Robo2 in COM muscles and is supported by the disrupted COM–heart cell contact in a muscle-specific knockdown of robo2 via RNAi (Fig. 4J). Because Slit is not restricted to lb-expressing anterior cardioblasts, the specificity of COM–heart interaction appears to be mediated by other mechanisms. On the other hand, loss of slit does not prevent COMs from interacting with HANC cells (Fig. 4H), indicating that COMs can be attracted in a slit-independent way. There is also a possibility that, in slit mutants, the slowly moving HANCs hold COMs far from the source of attractive signals (heart tip), thereby hampering the ability of COMs to grow toward the heart. The importance of proper HANC cell migration on the interaction between COMs and tip of the heart is further supported by the loss of cardiac COM's attachment in shg mutant embryos (Fig. 4I). Thus, it turns out that for growing COMs to reach the heart tip, they need to interact with properly migrating HANC cells. Both migration of HANC cells and attraction of COMs to the heart tip are compromised in slit mutant embryos revealing a pivotal role of Slit/Robo pathway in OFT assembly.

Fig. 4.

Slit, robo, robo2, and shg control the migration of HANC cells and OFT assembly. (A–F) Dorsal views of stage 14–15 embryos. (A) In wild-type embryo, HANCs (arrow) contact the cardiac cells at segment T2 (white vertical line). (B–D) In slit2, double roboGA285;robo24, and shg2 mutant embryos, HANC migration was delayed (arrows in T1 segment). (B) Notice that loss of sli causes also delayed migration of a subset of Lbe-expressing pericardial cells. (E) In contrast, in slit2/+;dock04273/+ transheterozygous embryos, HANC migration remained unaffected. (F) In slit2/+;shg2/+ embryos, the position of HANC cells was more anterior than in the wild type, suggesting that sli and shg interact to control HANC migration. (G–J) Lateral views of the OFT from stage-16 (G and J) and stage-15 (H and I) embryos. (G) In wild-type embryos, the HANCs and COMs are attached to the Lbe-positive cardioblasts. (H) In slit mutant embryos, COMs are attached to the HANCs (arrow), extending some filopodia (arrowhead) toward the heart. The distance between HANCs and the aorta (square bracket) is shown. (I) In shg mutant embryos, like in slit mutants, the COMs associate with HANCs but are not attached to the heart tip, which is detected far from them (square bracket). Notice that the number of HANC cells appears reduced in shg mutants. (J) The 24B-GAL4-driven attenuation of robo2 via RNAi renders the COMs unable to contact cardiac cells. Notice that the ACB cells form a funnel-shaped OFT-like structure (arrowhead). T1 and T2, thoracic segment 1 and 2, respectively. (Scale bars: A–F, 50 μm; G–J, 10 μm.)

Table 1.

HANC cell migration phenotypes in different mutant embryos affecting shg, slit, robo, and dock functions

| Genotype | Percentage of stage 14/15 embryos with HANCs located anteriorly to T2 |

|---|---|

| Wt | 0 |

| Sli2 | 87 |

| Sli2/+ | 3 |

| Shg2 | 90 |

| Shg2/+ | 6 |

| ShgK03401 | 80 |

| ShgK03401/+ | 3 |

| Sli2/+, Shg2/+ | 43 |

| RoboGA285 | 33 |

| RoboGA285/+ | 3 |

| Robo24 | 60 |

| Robo24/+ | 6 |

| RoboGA285, Robo24 | 70 |

| RoboGA285, Robo24/+ | 10 |

| Sli2/+, Robo GA285/+ | 40 |

| Sli2/+, Robo2 4/+ | 53 |

| Dock04723 | 13 |

| Dock04723/+ | 3 |

| Sli2/+, Dock04723/+ | 27 |

| Tin-Gal4; UAS-Shg RNAi | 36 |

| Tin-Gal4; UAS-Sli RNAi | 23 |

| Esg-Gal4; UAS-Shg RNAi | 30 |

| Esg-Gal4; UAS-Sli RNAi | 20 |

At least 30 age-matched embryos stained for cardiac cells (Tin) and HANC cells (Lbe) were inspected for each genotype.

Cardiac OFT Assembly Reveals Additional Parallels Between the Drosophila and Vertebrate Heart Development.

It is widely accepted that there are important similarities between the genetic control mechanisms that drive early heart development in Drosophila and in many other species (1). On the other hand, the mammalian heart undergoes a complex morphogenesis, leading to the formation of a four-chambered heart, whereas the Drosophila heart is a simple linear tube subdivided on the posterior part forming the heart proper and the anterior aorta. Thus, the later aspects of heart morphogenesis were thought to be specific to vertebrates. However, our previous analysis (20) has revealed that the anterior part of the Drosophila cardiac tube undergoes complex morphogenesis leading to the formation of the cardiac outflow tract, which, like in vertebrates, involves a population of nonmesodermal cells. Here, we provide further evidence that OFT forms by coordinated migration and cell type-specific interactions of multiple cellular components (Fig. 5).

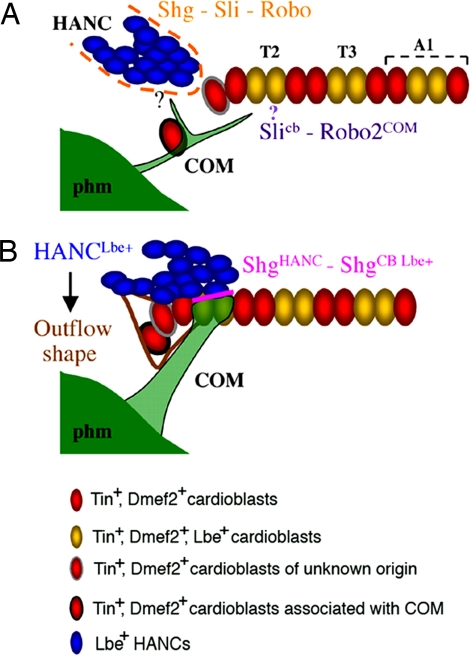

Fig. 5.

Model of the cardiac outflow tract assembly. (A) Early stage 14. The migration of HANC cells toward the heart and the association with cardiac cells depends on the Slit-Robo-Shg interaction. Slit expressed in the cardioblasts is expected (?) to attract the COM muscles toward the heart. The HANC-induced attraction of COM is independent of Slit, thereby raising the question as to the HANC-emitted attraction cue(s). A pair of ACBs (red cell with black circumference) is associated with COM. (B) Stage 16. The HANC cells overlap the aorta from the dorsal side, and the COMs are attached selectively to the Lbe-positive cardioblasts. The cell adhesion molecule Shg accumulates between HANCs and Lbe-positive cardioblasts (pink line). The ACBs contribute form the funnel-shaped tip of the heart. The particular OFT morphogenesis is HANC-dependent and is not seen in embryos in which HANCs were experimentally ablated. At stage 16, there are 14 cardioblasts within the anterior aorta. The origin of the red cell with gray circumference remains to be determined.

HANC cells, a major OFT component (Fig. 5), like the vertebrate cardiac neural crest cells, undergo migration, associate with cardiac primordia, and contribute to the final heart morphogenesis. A conserved family of Lbx/Lb homeodomain transcription factors is required for specification of both the Drosophila HANC and the vertebrate cardiac neural crest cells (20, 23). As demonstrated here, the rate of HANC migration and the precise HANC–heart tip cell–cell recognition are regulated by the Slit/Robo/Shg pathway, which emerges as an effective system for controlling multicomponent organ assembly. Interestingly, the slit function is also required for proper migration of the neural crest cells (24, 25) revealing that common signaling molecules are involved in Drosophila and in vertebrate OFT formation. In addition, the cells originating from the pharyngeal mesoderm (secondary heart field) in vertebrates (21) and the pharyngeal COM muscles with a pair of associated ACBs described appear to have a highly specialized cardiogenic function. In Drosophila, COMs contribute to the positioning of the heart tip (20), whereas the ACBs use COMs as a scaffold, associate with the aorta, and form the distal aspect of the OFT (Fig. 5B). Moreover, the funnel-like shape of the ACBs and the proper attachment of COMs to the heart are HANC-dependent, making additional link between OFT components and suggesting the existence of a HANC-derived secreted factor(s) controlling the final shape of the heart tip.

Thus, the genetic control mechanisms and cellular components that contribute to cardiac OFT development further extend the homology between Drosophila and vertebrate heart formation.

Materials and Methods

Fly Stocks.

The following mutant alleles were obtained from Bloomington Stock Center: slit2, shg2, shgk03401, and dock04723. The roboGA285;robo24, roboGA285, and robo24 mutant alleles were kindly provided by B. Dickson (Research Institute of Molecular Pathology, Vienna) (31). Mutant stocks were balanced with CyO, wg-lacZ to allow homozygous mutant embryos selection. The overexpression experiments were performed by using the UAS-GAL4 system (32). The following GAL4 and UAS lines were used: Esg-GAL4 (NP: 5130; Kyoto Stock Center), 24B-GAL4 (32), Slit-GAL4 (from G. Technau, University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany), Tin-GAL4 (from R. Bodmer, Burnam Institute for Medical Research, La Jolla, CA), UAS-Robo2 RNAi, UAS-rpr, UAS-nlsGFP (Bloomington Stock Center), Gal4-P0206;UAS-mcD8/GFP (from C. Klämbt, Univesität Münster, Münster, Germany). The ubi-DE-cad-GFP (33) was from T. Lecuit (Université de la Méditerranée, Marseille, France).

Staining of Embryos.

The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-Lbe (1:2,500) (8); goat anti-LacZ (1:1,000; Biogenesis); rabbit anti-Tin (1:800; from M. Frasch, University of Erlangen–Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany) (34); guinea pig anti-Msp300 (1:2000; from T. Volk, Weizman Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel) (35); rabbit anti-Mef2 (1:1,000; from H. Nguyen, University of Erlangen–Nürnberg) (36); rabbit anti-Robo2 (1:100; from B. Dickson) (31); goat anti-GFP (ab5450, 1:500; Abcam); rat anti-DE-cadherin (DCAD2, 1:20), mouse anti-Slit (C555.6D, 1:10), and mouse anti-Robo (13C9, 1:10) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA).

The anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, anti-guinea pig, anti-goat, and anti-rat secondary antibodies made in donkey and conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, CY3, or CY5 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used (1:300). For anti-Slit and anti-Robo detection, sheep anti-mouse antibodies conjugated to Biotin (dilution 1:1,000), followed by Streptavidin-DTAF (dilution 1:300) were used. All of the preparations were visualized on Zeiss LSM 510 Meta or Olympus FV300 confocal microscopes. Three-dimensional reconstructions and image analyses were performed by using Volocity (Improvision) software (see SI Text). In situ hybridization using anti-sense RNA shg probe targeting the 3′ region of the gene was performed according to the standard procedure (8). Signals were amplified by using TSA amplification reagent (PerkinElmer).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Association Française Contre les Myopathies, the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, and European Grant LSHG-CT-2004-511978 to the European Muscle Development (MYORES) Network of Excellence.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0706402105/DC1.

References

- 1.Olson EN. Science. 2006;313:1922–1927. doi: 10.1126/science.1132292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaffran S, Frasch M. Circ Res. 2002;91:457–469. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000034152.74523.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rizki TM. In: The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila. Ashburner M, Wright TRF, editors. New York: Academic; 1978. pp. 397–452. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rugendorff A, Younossi-Hartenstein A, Hartenstein V. Roux's Arch Dev Biol. 1994;203:266–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00360522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han Z, Olson EN. Development. 2005;132:3525–3536. doi: 10.1242/dev.01899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azpiazu N, Frasch M. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1325–1340. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodmer R. Development. 1993;118:719–729. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jagla K, Frasch M, Jagla T, Dretzen G, Bellard F, Bellard M. Development. 1997;124:3471–3479. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gajewski K, Choi CY, Kim Y, Schulz RA. Genesis. 2000;28:36–43. doi: 10.1002/1526-968x(200009)28:1<36::aid-gene50>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo PC, Frasch M. Mech Dev. 2001;104:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward EJ, Skeath JB. Development. 2000;127:4959–4969. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.22.4959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reim I, Frasch M. Development. 2005;132:4911–4925. doi: 10.1242/dev.02077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez AD, Shi W, Wilson BA, Skeath JB. Development. 2003;130:3015–3026. doi: 10.1242/dev.00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molina MR, Cripps RM. Mech Dev. 2001;109:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaffran S, Reim I, Qian L, Lo PC, Bodmer R, Frasch M. Development. 2006;133:4073–4083. doi: 10.1242/dev.02586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo PC, Skeath JB, Gajewski K, Schulz RA, Frasch M. Dev Biol. 2002;251:307–319. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponzielli R, Astier M, Chartier A, Gallet A, Therond P, Semeriva M. Development. 2002;129:4509–4521. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo PC, Frasch M. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2003;13:182–187. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(03)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perrin L, Monier B, Ponzielli R, Astier M, Semeriva M. Dev Biol. 2004;272:419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zikova M, Da Ponte JP, Dastugue B, Jagla K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12189–12194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133156100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly RG, Buckingham ME. Trends Genet. 2002;18:210–216. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02642-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schafer K, Neuhaus P, Kruse J, Braun T. Circ Res. 2003;92:73–80. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000050587.76563.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoller JZ, Epstein JA. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Bellard ME, Rao Y, Bronner-Fraser M. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:269–279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jia L, Cheng L, Raper J. Dev Biol. 2005;282:411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian L, Liu J, Bodmer R. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2271–2278. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacMullin A, Jacobs JR. Dev Biol. 2006;293:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santiago-Martinez E, Soplop NH, Kramer SG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12441–12446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605284103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramer SG, Kidd T, Simpson JH, Goodman CS. Science. 2001;292:737–740. doi: 10.1126/science.1058766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haag TA, Haag NP, Lekven AC, Hartenstein V. Dev Biol. 1999;208:56–69. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajagopalan S, Nicolas E, Vivancos V, Berger J, Dickson BJ. Neuron. 2000;28:767–777. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brand AH, Perrimon N. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oda H, Tsukita S. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:493–501. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin Z, Xu XL, Frasch M. Development. 1997;124:4971–4982. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.24.4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenberg-Hasson Y, Renert-Pasca M, Volk T. Mech Dev. 1996;60:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00602-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bour BA, O'Brien MA, Lockwood WL, Goldstein ES, Bodmer R, Taghert PH, Abmayr SM, Nguyen HT. Genes Dev. 1995;9:730–741. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Velasco B, Mandal L, Mkrtchyan M, Hartenstein V. Dev Genes Evol. 2006;216:39–51. doi: 10.1007/s00427-005-0029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schimmelpfeng K, Gogel S, Klambt C. Mech Dev. 2001;106:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan X, Labrador JP, Hing H, Bashaw GJ. Neuron. 2003;40:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pacquelet A, Rorth P. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:803–812. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.