Abstract

The phytohormone cytokinin regulates plant growth and development. This hormone is also synthesized by some phytopathogenic bacteria, such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and is as a key factor in the formation of plant tumors. The rate-limiting step of cytokinin biosynthesis is catalyzed by adenosine phosphate-isopentenyltransferase (IPT). Agrobacterium IPT has a unique substrate specificity that enables it to increase trans-zeatin production by recruiting a metabolic intermediate of the host plant's biosynthetic pathway. Here, we show the crystal structures of Tzs, an IPT from A. tumefaciens, complexed with AMP and a prenyl-donor analogue, dimethylallyl S-thiodiphosphate. The structures reveal that the carbon-nitrogen-based prenylation proceeds by the SN2-reaction mechanism. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to determine the amino acid residues, Asp-173 and His-214, which are responsible for differences in prenyl-donor substrate specificity between plant and bacterial IPTs. IPT and the p loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases likely evolved from a common ancestral protein. Despite structural similarities, IPT has evolved a distinct role in which the p loop transfers a prenyl moiety in cytokinin biosynthesis.

Keywords: Agrobacterium tumefaciens, crystal structure, isopentenyltransferase, trans-zeatin, p loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases

Cytokinins regulate a number of agronomically important aspects of plant growth and development, such as leaf senescence (1), apical dominance (2, 3), and reproductive competence (4, 5). This hormone is also synthesized by phytopathogenic bacteria, such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Pseudomonas savastanoi, and is as a key factor in the formation of plant tumors (6). The major natural cytokinins, such as trans-zeatin and N6-(Δ2-isopentenyl)adenine, are adenine derivatives that carry an isoprene-derived side chain at the N6 terminus (7, 8). The initial and rate-limiting step in cytokinin biosynthesis is N-prenylation of adenosine 5′-phosphate, a reaction catalyzed by adenosine phosphate-isopentenyltransferase (IPT; EC 2.5.1.27) (9, 10). Plants and Agrobacterium both synthesize cytokinin, but there is little similarity in their IPT primary structures [see supporting information (SI) Fig. 6], and their enzymatic properties are different. IPTs from higher plants predominantly use ATP or ADP as a prenyl acceptor and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) as the donor (11), but Agrobacterium IPTs, such as Tmr and Tzs, use AMP and 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate (HMBDP) or DMAPP as substrates (see SI Fig. 7) (12–14). Both types of IPT require a divalent metal ion, such as Mg2+ (10, 11). The distinction in cytokinin biosynthesis substrates can be attributed in Agrobacterium to the efficient production of trans-zeatin, a highly active cytokinin species. In host plants, the use of HMBDP, a metabolic intermediate in the methylerythritol phosphate pathway, enables Tmr to produce trans-zeatin nucleotide directly without using the host's hydroxylating system (13, 15).

There are two isoenzymes of IPT in Agrobacterium, Tmr and Tzs, and their substrate preference is similar (SI Fig. 7) (14). The Tzs gene is located in the virulence region of nopaline-type Ti-plasmids (16). Tzs stimulates T-DNA transfer efficiency (16, 17), whereas Tmr, which is encoded in the T-DNA region, induces tumorigenesis in host plant cells (10, 18).

Although there is a long history of cytokinin research from biological and agronomic perspectives that has provided a wealth of knowledge about plant development and plant–microbe interactions, understanding the structural basis for the reaction mechanism, substrate specificity, and evolution of cytokinin biosynthesis has been lacking. Here, we have determined four types of crystal structures of Tzs from A. tumefaciens, complexed with a natural substrate or its analogue. The structures provide a structural insight into the reaction mechanism and unique evolution of cytokinin biosynthesis. A structure-based mutagenesis study of Tzs was used to identify the crucial amino acid residues that determine prenyl-donor substrate specificity differences between Tzs and higher-plant IPTs.

Results and Discussion

Structure of Tzs.

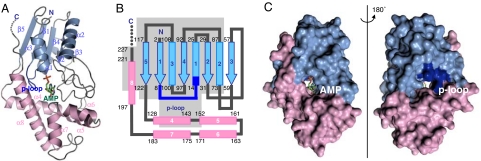

The crystal structure of Tzs was solved at 2.31-Å resolution by a multiwavelength anomalous dispersion method with selenomethionine-labeled (SeMet) protein. Tzs consists of two domains: the N-terminal domain (residues 1–126) that comprises a five-stranded parallel β-sheet (β1–β5) surrounded by three α-helices (α1–α3), and the C-terminal domain (residues 127–227) that comprises five helices (α4–α8; Fig. 1 A and B). The N-terminal domain contains a nucleotide-binding p loop motif (Gly-8-Pro-Thr-Cys-Ser-Gly-Lys-Thr-15) (19). The C-terminal side of the terminal helix (α8) extends to the N-terminal domain, and the C terminus is attached to the N-terminal domain (Fig. 1 A–C). An interface between the domains forms a solvent-accessible channel that connects the two sides of the molecular surface (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Structure of Tzs-AMP. (A) Ribbon model. The N- and C-terminal domains and the p loop are light blue, pink, and dark blue, respectively. Carbon, oxygen, phosphorous, and nitrogen atoms of the AMP molecule are green, red, orange, and blue, respectively. In our structure, residues from 228 to the C terminus are disordered. (B) Topology model. The α-helices and β-strands are shown as rectangles and arrows, respectively. A gray background indicates the region that is structurally related to the p loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase superfamily (see text for details). (C) Surface model of Tzs. Molecular surface of the AMP-binding side of the reaction channel (Left) and the opposite site (Right), which is rotated by 180° around the vertical axis.

Binding of AMP.

An electron density map of the Tzs crystal showed that it binds to a compound in the solvent-accessible channel. Electron density, mass spectrum, and absorbance spectrum analyses revealed that the compound is AMP (SI Fig. 8). Thus, the crystal was named as Tzs-AMP. In the Tzs-AMP crystal structure, the AMP molecule occludes one side of the channel, with the adenine ring positioned deep within (Fig. 2A). The phosphate group is fixed by four hydrogen bonds from the N-terminal end of α3 (residues 99–101), and by a charge–charge interaction and hydrogen bond to Arg-34 (Fig. 3A). The N6-amino group of the adenine ring, the prenylation site, forms hydrogen bonds to Asp-33 and Ser-45 (Fig. 3A). Val-35 forms a van der Waals interaction with the ring, and Asp-171 in the C-terminal domain hydrogen bonds to the 2′-hydroxyl group of AMP (Fig. 3A). However, the p loop, which is located on the other side of the channel, does not form any interaction with AMP.

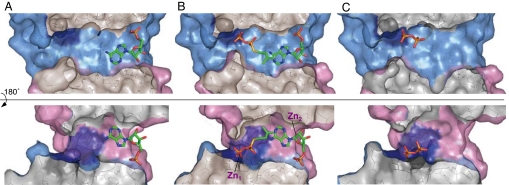

Fig. 2.

Cutaway views of the reaction channel. The surface of the channel formed by the N-terminal domain in Tzs-AMP (A), Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn (B), and Tzs-PPi (C). The sulfur atom is shown in violet. Cross-sectional surfaces are gray.

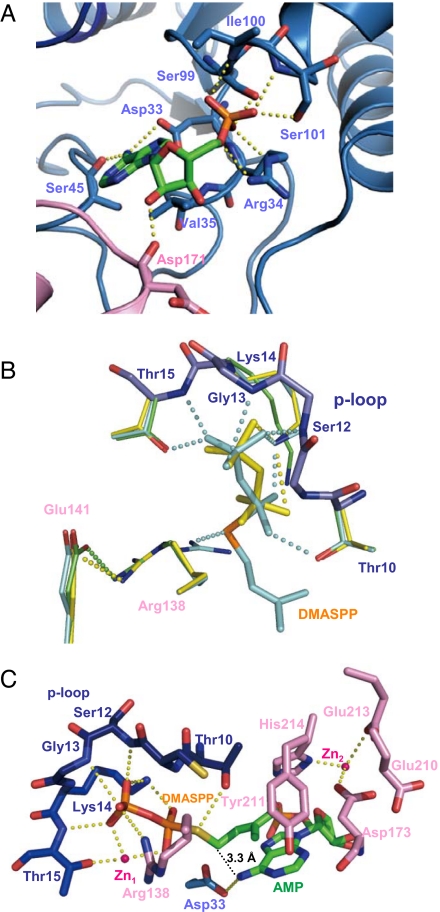

Fig. 3.

Active site of Tzs. (A) Binding of AMP in Tzs-AMP. Hydrogen bonds and charge–charge interactions are shown as yellow dashed lines. (B) Superimposed structures of the reaction centers of Tzs-AMP (green), Tzs-AMP/DMASPP (cyan), and Tzs-PPi (yellow). Side chains of Cys-11 and Ser-12 on the p loop are not shown. (C) Binding of DMASPP and AMP in Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn. For clarity, only side chains are shown in Asp-33, Arg-138, Asp-173, Tyr-211, and His-214. The N- and C-terminal domains, and the p loop are light blue, pink, and dark blue, respectively. Carbon, oxygen, phosphorous, and nitrogen atoms of the AMP molecule are green, red, orange, and blue, respectively.

Binding of the Prenyl-Donor Analogue and Zn2+ to Tzs.

To better understand the reaction mechanism of cytokinin biosynthesis, Tzs-AMP was soaked in dimethylallyl S-thiodiphosphate (DMASPP), DMASPP and Zn2+, or DMAPP. Structures of the resulting crystals, designated as Tzs-AMP/DMASPP, Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn, and Tzs-PPi were determined at 2.10-Å, 2.10-Å, and 2.80-Å resolutions, respectively. DMASPP is a substrate analogue of DMAPP, whose cleavage site oxygen atom (C1–O1) is substituted by a sulfur atom (20). In the Tzs-AMP/DMASPP crystal structure, AMP and DMASPP are visible within the electron density signal of the channel (SI Fig. 9A). The diphosphate moiety of DMASPP binds to the loop by hydrogen bonds and charge–charge interactions, and the sulfur atom is fixed by a hydrogen bond to the guanidinium group of Arg-138 (Fig. 3B). The electron density of two Zn2+ atoms (Zn1 and Zn2) appears in the channel of the Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn crystal structure in addition to AMP and DMASPP (SI Fig. 9B). DMASPP enters the channel from the side opposite the AMP-accessing site (Figs. 2B). The diphosphate moiety of DMASPP binds to Arg-138 by a charge–charge interaction, and to the p loop coordinating with Zn1 (Fig. 3C). Thr-10 forms a hydrogen bond to the sulfur atom of DMASPP in Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn. However, the AMP-binding mode of Tzs-AMP/DMASPP and Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn was the same as Tzs-AMP (data not shown). The dimethylallyl group of Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn is located almost parallel to the adenine ring of AMP at an angle of 9.7°, and makes van der Waals contacts with the adenine ring and the side chains of Asp-173, Tyr-211, and His-214. The distance for N-prenyl transfer between the carbon (C1) and nitrogen (N6) atoms is 3.3 Å (Fig. 3C). In the Tzs-PPi crystal, the electron density of the AMP molecule disappears, and a diphosphate appears instead at the p loop (Fig. 2C and SI Fig. 9C), indicating that the enzymatic reaction proceeds in the crystal, and that the solvent-accessible channel is its reaction center. The reaction in the crystal probably uses Mg2+ in the crystallization solution. The diphosphate is fixed to Lys-14 by a hydrogen bond or charge–charge interaction.

Proposed Reaction Mechanism.

Structural comparisons among the four crystal structures show that binding of a substrate or its analogue induces drastic changes in the arrangement and interactions of amino acid side chains, which are involved in the reaction process. Arg-138 forms a charge–charge interaction with Glu-141 in Tzs-AMP and Tzs-PPi, a hydrogen bond to the sulfur atom of DMASPP in Tzs-AMP/DMASPP, and a charge–charge interaction with the β-phosphate of DMASPP across the channel in Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn (Fig. 3 B and C). The hydroxyl group of Thr-10 forms a hydrogen bond to the sulfur atom of DMASPP in Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn, but forms a hydrogen bond to the α-phosphate in Tzs-AMP/DMASPP (Fig. 3 B and C). These tight interactions of Thr-10 and Arg-138 with DMASPP strongly suggest that the side chains facilitate the elimination of diphosphate by stabilizing the oxygen atom at the cleavage site in the transition state of the enzymatic reaction. Substitution of Thr-10 or Arg-138 with Ala severely reduces catalytic activity, an observation that supports this model (SI Fig. 10). The metal ion at position Zn1 plays a role in neutralizing the negative charge of diphosphate and in fixing DMASPP at the appropriate position to undergo catalytic reaction.

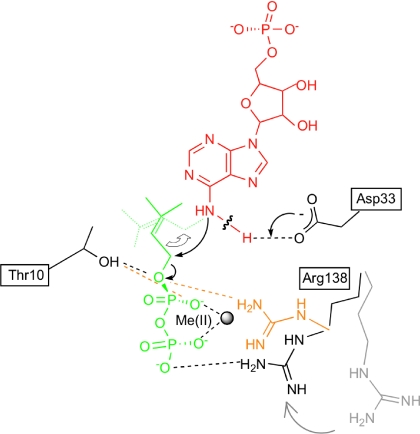

A proposed reaction model is shown in Fig. 4. The side chain of Asp-33 interacts with the N6 position of AMP (Fig. 3A), suggesting that Asp-33 functions as a general base by the deprotonation of the N6-amino group of AMP. Elimination of Tzs activity by substitution of Asp-33 with Ala supports this model (SI Fig. 10). In an IPT from hops (Humulus lupulus), Asp-62, which corresponds to Asp-33 of Tzs, is also indispensable for the enzymatic reaction (21). It should be noted that Thr-10, Asp-33, and Arg-138 are fully conserved among all IPTs (SI Fig. 6). Based on these results, we suggest that the IPT carbon-nitrogen-based prenylation reaction proceeds by the Sn2-reaction mechanism (Fig. 4) that is involved in carbon–carbon-based or carbon–oxygen-based prenylation of aromatic substrates (22), and farnesyl modification of proteins (23).

Fig. 4.

Proposed chemical reaction model of prenyl transfer from DMAPP to AMP in Tzs. Prenyl transfer proceeds by the SN2-nucleophilic displacement reaction. AMP is shown in red, DMAPP in green, and the amino acid residues of Tzs in black. Arg-138 in the absence of divalent metal ion [Me(II)] is shown in orange, and in the absence of prenyl-donor substrate in gray. The hydrogen-bonding network among the substrates and Thr-10, Asp-33, Arg-138, and Me(II) found in the Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn and Tzs-AMP/DMASPP is indicated as a dashed line. In this model, the carboxylate group of Asp-33 serves as a general base to deprotonate the N6-amino group of AMP. The resulting nucleophile attacks the carbon (C1) of DMAPP. Collapse of the penta-covalent transition state yields the products N6-(Δ2-isopentenyl)adenine riboside 5′-monophosphate and diphosphate. Thr-10 and Arg-138 stabilize the penta-covalent transition state.

Two Zn2+ Ions Are Present in Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn.

As described above, two Zn2+ ions are present in the Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn crystal. One (Zn1) is closely associated with DMASPP and is coordinated with the hydroxyl group of Thr-15 and two oxygen atoms of each of the α- and β-phosphate groups of DMASPP (Fig. 3C). The other (Zn2) is located near AMP and is coordinated to the side chains of Asp-173, Glu-213, and His-214 (Fig. 3C). The side-chain conformation of Glu-213 is altered between Tzs-AMP/DMASPP and Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn, but those of Asp-173 and His-214 are not (data not shown). Substitution of Glu-213 with Gln does not affect reactivity (Table 1). In contrast to Thr-10, Asp-33, and Arg-138, Glu-213 is not well conserved among IPTs (SI Fig. 6). In addition, the side-chain conformation of Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn around the AMP is similar to Tzs-AMP and Tzs-AMP/DMASPP, and there is no difference in the binding of AMP to Tzs among the three structures (data not shown). Thus, the biochemical significance of the Zn2 ions is unclear at present.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of recombinant IPTs

| Enzyme | Substrate | Km, μM | Vmax, nmol·min−1·mg protein−1 | kcat, min−1 | kcat/Km, min−1/M−1 | Sp. ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tzs | DMAPP | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 119.0 ± 10.1 | 3.2 | 4.1 × 105 | 2.3 |

| HMBDP | 8.2 ± 0.4 | 55.0 ± 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.8 × 105 | ||

| AMP | 0.035 ± 0.005 | |||||

| TzsD173G | DMAPP | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 50.8 ± 1.4 | 1.4 | 5.4 × 105 | 208 |

| HMBDP | 22.6 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 5.8 × 10−2 | 2.6 × 103 | ||

| TzsE210N | DMAPP | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 51.4 ± 0.7 | 1.4 | 3.3 × 105 | 15.0 |

| HMBDP | 26.1 ± 1.1 | 22.5 ± 0.7 | 0.6 | 2.2 × 104 | ||

| TzsY211T | DMAPP | 35.4 ± 2.1 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 0.13 | 3.6 × 103 | 9.0 |

| HMBDP | 33.5 ± 1.5 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.4 × 10−2 | 4.0 × 102 | ||

| TzsE213Q | DMAPP | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 72.5 ± 2.6 | 2.0 | 2.6 × 105 | 5.1 |

| HMBDP | 27.2 ± 0.8 | 51.5 ± 1.0 | 1.4 | 5.1 × 104 | ||

| TzsH214L | DMAPP | 10.8 ± 0.9 | 199.0 ± 16.0 | 5.4 | 5.0 × 105 | 1163 |

| HMBDP | 80.5 ± 9.6 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 3.5 × 10−2 | 4.3 × 102 |

The Km values for DMAPP and HMBDP were measured by using a nonradioisotope assay (30) with AMP (50 μM), and for AMP with DMAPP (100 μM). Means ± SD (n = 3). Sp. ratio, specificity ratio: the kcat/Km for DMAPP divided by the kcat/Km for HMBDP.

Identification of Amino Acid Residues Controlling Prenyl-Donor Substrate Specificity.

The Glu-210 to His-214 region of α8 and Asp-173 on loop α6-α7 form a cavity for a prenyl moiety, and the side chains of His-214 and Asp-173 present a hydrophilic region on the surface of the reaction cavity surrounding the trans-side end of the dimethylallyl group. To assess which amino acid residue(s) determine substrate preference differences between bacterial and plant IPTs, we introduced amino acid substitutions into Tzs and evaluated the resulting kinetic parameters (Table 1). There were no severe negative effects on reactivity to DMAPP except for the Tyr-211 substitution, which greatly reduced reactivity to both prenyl donors. Although each substitution reduced relative reactivity to HMBDP, substitution of His-214 with Leu or Asp-173 with Gly greatly reduced both affinity and catalytic activity (Table 1). As a result, the specificity ratio (kcat/Km for DMAPP divided by kcat/Km for HMBDP) of TzsH214L and TzsD173G for DMAPP/HMBDP increased 505- and 90-fold, respectively. These results indicate that the hydrophilic region formed by the side chains of His-214 and Asp-173 determine the specificity of the prenyl donor in Tzs, thus allowing the use of HMBDP for direct synthesis of trans-zeatin, a highly active cytokinin.

To identify the critical amino acids governing prenyl-donor substrate specificity in higher-plant IPTs, we changed each of five positions of AtIPT4, an Arabidopsis IPT, to the corresponding residue of Tzs. However, there was no significant difference in HMBDP utilization associated with these mutations (SI Fig. 11). Additional amino acids would thus be necessary to identify the loci responsible for efficient utilization of HMBDP by plant IPTs.

As for the prenyl-acceptor substrate, Tzs exclusively uses AMP, whereas plant IPT uses either ADP or ATP. The Arg-34 and Ile-100 residues, which fix the phosphate group of AMP (Fig. 3A), are conserved with Lys and Asn, respectively, at the corresponding position of plant IPTs (SI Fig. 6). We substituted Arg-34 with Lys, Ile-100 with Asn, or both into Tzs. However, none of the three mutant enzymes were able to use ADP or ATP, nor did they lose catalytic activity (SI Fig. 12), suggesting that the specificity for prenyl-acceptor substrate is controlled by more than these two amino acid sites.

Molecular Evolution of IPT.

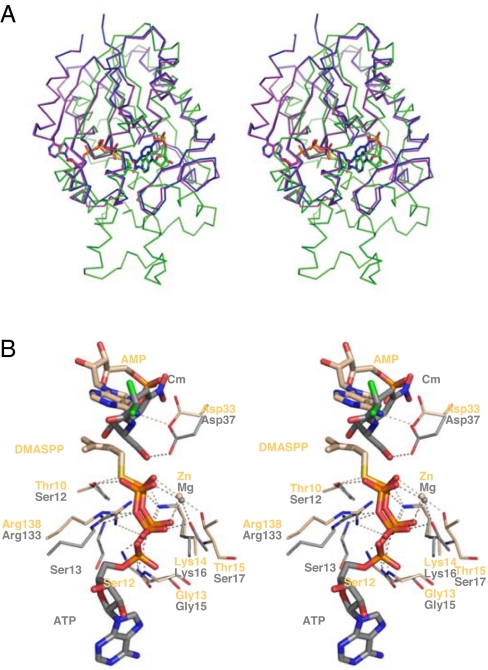

A three-dimensional structure DALI database search (24) revealed that the N-terminal domain of Tzs (residues 1–126) is structurally related to the p loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase (pNTPase) superfamily (8.1 ≥ Z ≥ 7.1). The α4 helix, the C-terminal part of α8, and the C terminus, all of which are close to the N-terminal domain in the tertiary structure, also have structural similarity to pNTPases (Fig. 1B). Among the pNTPases, notable similarity is found in and around the active site of chloramphenicol phosphotransferase from Streptomyces venezuelae [CPT (25, 26); Z = 7.7, rmsd of 3.1 Å for 132 Cα atoms] (Fig. 5A). CPT catalyzes the transfer of the γ-phosphate of ATP to the C-3 hydroxyl group of chloramphenicol, and the p loop binds to the β- and γ-phosphates of ATP, directly taking part in the cleavage and transfer of the γ-phosphate (25, 26). Superimposition of the reaction centers of Tzs and CPT (Fig. 5B) indicates that the interaction of the diphosphate moiety to the p loop is quite similar despite the different binding substrate, with an altered orientation.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of Tzs with CPT. (A) The Cα backbones of CPT-ATP (magenta) and CPT-Cm (blue) were superimposed onto Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn (green). AMP, DMASPP, ATP, and CPT are also shown. (B) Comparison of the catalytic sites of Tzs (light orange) and CPT (gray). Substrates and metal ions of the two structures are also shown. Interacting residues of Tzs are labeled. Cm, chloramphenicol.

Comparison of the structures also suggests that the functions of Asp-33 and Arg-138 in Tzs are equivalent to those of Asp-37 and Arg-133 in CPT (Fig. 5B): the Asp residue is proposed as a general base that deprotonates the conjugation site, and the Arg residue stabilizes the transferred group in catalysis (25, 26). Although IPT and CPT might have evolved from a common ancestral protein, IPT appears to have uniquely evolved to catalyze N-prenyl transfer to adenosine phosphate, because all of the other enzymes of the pNTPase superfamily catalyze transfer of a phosphate or sulfate group to the countersubstrate. During molecular evolution of IPT, the p loop must have been conserved to fix a diphosphate moiety of the donor substrate, but its function has changed to bind prenyl diphosphate (DMAPP or HMBDP) and to transfer the prenyl group, but not a phosphate group, to adenosine phosphate.

Conclusions

We have determined the crystal structures of natural substrate- and substrate analogue-bound forms of Agrobacterium IPT, which catalyzes the rate-limiting step of cytokinin biosynthesis. These structures provide the first insight into the reaction mechanism and molecular evolution of IPT. Structure-based mutagenesis pointed out two critical amino acid residues within the substrate-binding pocket that serve to distinguish the presence or absence of a hydroxyl group of the prenyl-donor substrate. These amino acids must be important for efficient Agrobacterium tumorigenesis because they create a metabolic bypass for direct trans-zeatin-type cytokinin production. The crystal structures also provide critical data for understanding the molecular evolution of cytokinin biosynthesis. Interestingly, the role of the p loop in IPT is distinct from that of other pNTPases, although they may have evolved from a common ancestral protein. Despite its obvious biological and agricultural importance, there are no inhibitors or modulators of cytokinin biosynthesis. These structural analyses may provide a template for the structure-based design of inhibitors of phytobacterial tumorigenesis and can help to develop plant growth regulators that modulate plant IPT activity.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

HMBDP (27) and dimethylallyl S-thiodiphosphate [(S)-3-methyl-2-buten-1-yl thiodiphosphate, DMASPP] (20) were synthesized by Wako Pure Chemical Industries.

Construction of Expression Plasmids.

For expression of Tzs and AtIPT4, the coding regions were amplified by PCR and cloned into expression vector pQE60 (Qiagen) to express His-tagged recombinant proteins (pQE-Tzs and pQE-IPT4, respectively). Site-directed mutants of Tzs (TzsT10A, TzsD33A, TzsR138A, TzsD173G, TzsE210N, TzsY211T, TzsE213Q, and TzsH214L) and AtIPT4 (IPTG191D, IPTN229E, IPTT230Y, IPTQ232E, and IPTL233H) were constructed by using QuikChange (Stratagene) according to the supplier's protocol.

Preparation of Tzs Proteins.

The Met-auxotroph Escherichia coli strain B834 (Novagen) harboring pREP4 (Qiagen) and pG-KJE8 (Takara Bio) was used as the host for the production of SeMet protein. The pQE-Tzs transformants were cultured with shaking in LeMaster medium supplemented with 1 M sorbitol and 25 μg/ml seleno-l-Met (28, 29), 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 1 ng/ml tetracycline, and 0.5 mg/ml d-arabinose at 37°C until the A600 was 0.5. The temperature of the medium was reduced to 25°C and isopropyl-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. Cultures were grown overnight with shaking, and cells were harvested and lysed with a sonicator. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 20 min and the supernatant was loaded onto a Ni-NTA superflow column (Qiagen) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 3.5 mM 2-merchaptoethanol. Adsorbed proteins were eluted with 500 mM imidazole. Gel filtration was successively performed on a HiLoad Superdex 75 prep-grade column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 25 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, and 3.5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. SeMet samples were dialyzed against 10 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.5 and 1 mM DTT. The expression and purification conditions for Tzs were the same as for SeMet-Tzs protein except that modified M9 medium (30) was used instead of LeMaster medium.

Crystallization and Data Collection.

Crystallization was performed by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. The drops consisted of 2 μl of a protein solution and 2 μl of a precipitating solution. Plate-like crystals (0.15 × 0.15 × 0.2 mm3) were obtained at 4°C after a few days in 1.4–2.0 M sodium formate, 5 mM Mg(OAc)2, and 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.8–5.4) when the protein solution was concentrated to 5 mg/ml. Protein crystals were also obtained with 15% (vol/vol) glycerol as a cryo-protectant in the solution. Crystallization conditions for native Tzs were the same as for SeMet-Tzs. Tzs-AMP/DMASPP and Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn crystals were obtained by introducing 0.5 μl of 20 mM DMASPP, 20 mM DMASPP, and 30 mM ZnCl2 into the crystallization drop [1.8 M sodium formate, 20% (vol/vol) glycerol and 100 mM sodium acetate pH 5.0], respectively, and incubating at 4°C for 15 h. For preparation of the Tzs-PPi crystal, 0.5 μl of 20 mM DMAPP was added to the Tzs crystallization drop and incubated at 4°C for 15 h. All crystals were flash-frozen in a nitrogen cold stream. X-ray diffraction data collections were performed on a SPring-8 beamline BL45XU (31) and processed by using HKL2000 software (32). Data collection statistics are listed in SI Table 2.

Structure Determination and Refinement.

The crystal structure of SeMet-Tzs was solved by a multiwavelength anomalous dispersion method by using the program SOLVE (33). Density modification and automated model building were performed with the program RESOLVE (34). Model building and manual fitting of the model were carried out by the program Xfit (35), and the model was partially refined by using the program CNS (36). Higher resolution of the native crystal, which has a different space group, was obtained in the process of building the initial model. Thus, the unfinished model of SeMet-Tzs was used for further analysis of the new crystal by the molecular replacement method. Finally, the model was refined with diffraction data from the new crystal, which was named native Tzs-AMP. Five percent of the reflections were set aside for Rfree calculations (37). The structures of Tzs-AMP/DMASPP and Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn were refined by rigid-body refinement by using Tzs-AMP, and that of Tzs-PPi by using SeMet-Tzs. Only the structure of Tzs-PPi was performed with noncrystallographic symmetry restraints during refinement. Finally, the models were refined by using the program REFMAC (38), including TLS refinement (39). The program AMoRe was used for the molecular replacement method (40). The quality of the final models was assessed by Ramachandran plots, and analysis of model geometry with the program PROCHECK (41). Refinement statistics are listed in SI Table 2. Secondary structure assignment was performed with the program PROMOTIF (42). Figures were created with the program PyMOL (43).

Enzyme Assays.

Activity of Tzs, AtIPT4, and the site-directed mutagenesis enzymes was measured by using a nonradioisotopic assay (30) with some modifications. The reaction was stopped by addition of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (10 units), and incubation for 10 min at 37°C. After addition of a one-tenth volume of 20% acetic acid to the mixture, it was subjected to HPLC (Alliance 2695/PDA detector 2996, Waters) with an ODS column (Symmetry C18, 3.5 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm cartridge, Waters). Cytokinin produced in the reaction was separated at a flow rate of 0.25 ml/min with a gradient of acetonitrile (solvent A) and 2% acetic acid (solvent B) set according to the following profile: 0 min, 1% A + 99% B; 1min, 1% A + 99% B; 20 min, 40% A + 60% B; 23 min, 60% A + 40% B; 30 min, 1% A + 99% B. The column temperature was 40°C. For determination of the Km values of Tzs for AMP and TzsH214L for HMBDP, reaction products were quantified by LC-MS because of their low reactivities. trans-[2H5]Zeatin riboside (0.5 pmol) was added to the reaction mixture after addition of acetic acid to determine recovery in the following steps. The reaction product was purified by passing through a reverse-phase column (Oasis HLB cartridge, Waters) and evaporated to dryness. The resulting materials were dissolved in 0.005% acetic acid and subjected to LC-MS (Alliance 2695/ZQ-MS2000, Waters) with an ODS column (Symmetry C18, 5 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm, Waters). Cytokinin riboside product was monitored with a positive ion mode of selected ion monitoring. Other conditions were as described in ref. 15.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank Dr. G. Kurisu for critical reading of this manuscript, M. Nanri for technical assistance, and Drs. M. Sato and H. Hashimoto for their help with preliminary crystallographic data collection. This work was supported by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Grant 18370023 (to H. Sakakibara).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 2ZE5 (Tzs-AMP), 2ZE6 (Tzs-AMP/DMASPP), 2ZE7 (Tzs-AMP/DMASPP/Zn, 2ZE8 (Tzs-PPi)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0707374105/DC1.

References

- 1.Gan S, Amasino RM. Science. 1995;270:1986–1988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sachs T, Thimann KV. Am J Bot. 1967;54:134–144. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka M, Takei K, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Mori H. Plant J. 2006;45:1028–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashikari M, Sakakibara H, Lin S, Yamamoto T, Takashi T, Nishimura A, Angeles ER, Qian Q, Kitano H, Matsuoka M. Science. 2005;309:741–745. doi: 10.1126/science.1113373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurakawa T, Ueda N, Maekawa M, Kobayashi K, Kojima M, Nagato Y, Sakakibara H, Kyozuka J. Nature. 2007;445:652–655. doi: 10.1038/nature05504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris RO. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1986;37:509–538. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mok DW, Mok MC. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2001;52:89–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakakibara H. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:431–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taya Y, Tanaka Y, Nishimura S. Nature. 1978;271:545–547. doi: 10.1038/271545a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akiyoshi DE, Klee H, Amasino RM, Nester EW, Gordon MP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5994–5998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.19.5994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kakimoto T. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:677–685. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackwell JR, Horgan R. Phytochemistry. 1993;34:1477–1481. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakakibara H, Kasahara H, Ueda N, Kojima M, Takei K, Hishiyama S, Asami T, Okada K, Kamiya Y, Yamaya T, Yamaguchi S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9972–9977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500793102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krall L, Raschke M, Zenk MH, Baron C. FEBS Lett. 2002;527:315–318. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takei K, Yamaya T, Sakakibara H. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41866–41872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.John MC, Amasino RM. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:790–795. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.790-795.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell GK, Hommes NG, Kuo J, Castle LA, Morris RO. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1988;1:235–242. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-1-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akiyoshi DE, Morris RO, Hinz R, Mischke BS, Kosuge T, Garfinkel DJ, Gordon MP, Nester EW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:407–411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saraste M, Sibbald PR, Wittinghofer A. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:430–434. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90281-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phan RM, Poulter CD. J Org Chem. 2001;66:6705–6710. doi: 10.1021/jo010505n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakano Y, Okada Y, Matsunaga A, Suwama T, Kaneko T, Ito K, Noguchi H, Abe I. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:2439–2446. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuzuyama T, Noel JP, Richard SB. Nature. 2005;435:983–987. doi: 10.1038/nature03668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long SB, Casey PJ, Beese LS. Nature. 2002;419:645–650. doi: 10.1038/nature00986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holm L, Sander C. Science. 1996;273:595–603. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izard T, Ellis J. EMBO J. 2000;19:2690–2700. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izard T. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1508–1513. doi: 10.1002/pro.101508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takei K, Dekishima Y, Eguchi T, Yamaya T, Sakakibara H. J Plant Res. 2003;116:259–263. doi: 10.1007/s10265-003-0098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeMaster DM, Richards FM. Biochemistry. 1985;24:7263–7268. doi: 10.1021/bi00346a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hendrickson WA, Horton JR, LeMaster DM. EMBO J. 1990;9:1665–1672. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takei K, Sakakibara H, Sugiyama T. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26405–26410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto M, Kumasaka T, Fujisawa T, Ueki T. J Synchrotron Radiat. 1998;5:222–225. doi: 10.1107/S0909049597014738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:849–861. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terwilliger TC. Acta Crystallogr D. 2000;56:965–972. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McRee DE. J Struct Biol. 1999;125:156–165. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brünger AT. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:366–396. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Lebedev A, Wilson KS, Dodson EJ. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:247–255. doi: 10.1107/S090744499801405X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN. Acta Crystallogr D. 2001;57:122–133. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900014736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Navaza J. Acta Crystallogr A. 1994;50:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hutchinson EG, Thornton JM. Protein Sci. 1996;5:212–220. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeLano WL. PyMol. Palo Alto, CA: Delano Scientific; 2002. Available at: http://pymol.sourceforge.net/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.