INTRODUCTION

Evidence-based assessment of the effectiveness of interventions is increasingly being adopted in disciplines beyond medicine [1, 2], and a particular area of interest is social care (care that helps people with daily living, personal care, and independence) [3–5]. The resulting increase in the demand for systematic reviews of the effectiveness of social care interventions [1, 2, 6] is challenging for systematic reviewers, particularly regarding how to best identify appropriate evidence for inclusion [1–4, 7–8]. A range of databases can provide evidence on the effectiveness of social care interventions [1, 2, 9], including general medical databases (e.g., EMBASE and MEDLINE) and the increasing number of databases available that focus on social care (e.g., Sociological Abstracts and Social Services Abstracts). Systematic literature searches of the evidence in this field are problematic for two reasons: the optimal number and combination of databases is unknown [1–4, 7–9] and the creation of combinations of search terms that retrieve all the relevant references is difficult [1, 2].

The selection of search terms in social care topics is also problematic due to variations in the terminology used, the country of origin, and changes over time [1]. For example, although the term “carer” is often used in the United Kingdom, terms such as “caregiver” or “caretaker” are used in the United States. In addition, phrases such as “children caring for their elderly relatives” or “husbands supporting their wives” can be substituted for “carer.” The use of different definitions of “carers” can also impact the searching process. For example, some definitions include paid workers, while others include only volunteers. To identify papers relating to paid caregivers terms such as “health personnel,” “care worker,” or “health care assistant” may be appropriate, while for volunteers terms such as “neighbor,” “friend,” or “spouse” are more appropriate.

With a wide range of potentially useful databases and a lack of standardized terminology, searching a large number of databases with broad search strategies encompassing many variants of the terminology seems the most effective way to ensure identification of most of the relevant studies. However, this approach may also retrieve large numbers of irrelevant records. The aim of this study was to ascertain the relative contributions of a range of potentially useful databases and other sources for identifying evidence for a systematic review of social care.

METHODS

This study examined which resources (e.g., databases, hand searching) yielded references used in a recent systematic review of the effectiveness of respite care for carers of frail older people [10]. The original review was conducted according to published guidance [11].

Search strategy

To identify relevant papers for the original review on respite care, reviewers searched a range of databases with medical and/or social care content, as well as databases of different types of publications (e.g., gray literature and conferences) and studies (e.g., economic evaluations and randomized controlled trials [RCTs]) (Table 1 online). Studies were also sought by checking references, searching citations of key papers, and contacting authors and organizations [10].

The review question comprised three search facets: “carers,” “frail elderly,” and “respite care.” After many search iterations, the review team decided that the search strategy should focus on the search facets “carers” and “respite care” and not include search terms for “frail elderly,” as the team's previous experience [12] and exploratory searches indicated that some relevant references did not specify any age category in the bibliographic records. To capture as many of the relevant records as possible and overcome the variation in terminology for “carers” and “respite care,” the search strategies incorporated many different synonyms for these terms (Table 2 online). The search strategy was adapted for use in each database.

Retrospective analysis

In the retrospective analysis reported here, the authors recorded whether all of the original review's references were identified in each resource, using the search strategy described above. The authors also conducted simple searches in the resources for the citations included in the original review to identify whether they were available in each resource at the time of searching. To establish if each record was available at the time of searching, the entry date of the record was compared to the date of the original search. For references available in a database but not identified by the original review's search strategy, the bibliographic record of the reference was examined for terms or phrases used to denote “carers” and “respite care” in the title, abstract, or indexing to determine why it had not been identified.

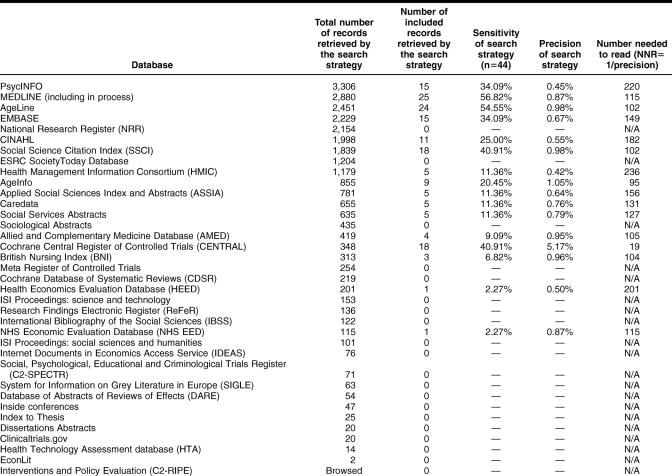

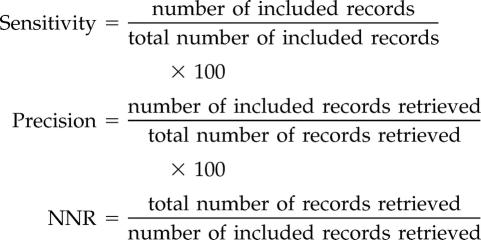

The sensitivity, precision, and number needed to read (NNR) were calculated for the search in each of the databases. NNR is an index of how many records need to be read to find one included record. The authors used the following definitions:

|

The minimum combination of databases required to identify all included studies was recorded. This analysis was also repeated with the subset of included RCTs.

RESULTS

References examined for the original review

The searches for evidence for the systematic review on respite care retrieved 13,092 unique records (25,374 before deduplication), and an additional 3,768 records (before deduplication) were retrieved from searches for ongoing studies. Searches in PsycINFO provided the greatest number of records, followed by MEDLINE and AgeLine (Table 3).

Table 3 Sensitivity, precision, and number needed to read for each database

Forty-four references were included in the systematic review: 57% (25/44) were RCTs; 30% (13/44) were quasi-experimental design (i.e., non-randomized controlled studies, where the control group may, for example, have been taken from a different geographic area and matched with the intervention group by age, gender, or clinical characteristics); and 14% (6/44) were uncontrolled studies. More than a third (16/44) of the included studies included an economic evaluation.

Most of the included references (37/44, 84%) were published as journal articles, 7% as books or book chapters (3/44), 5% as dissertations (2/44), 1 as a report, and 1 as a conference abstract.

Sources of included references

Where were the references available? Executing individual searches (e.g., author name, title word) in the resources for each of the references included in the original review, the authors found that 18 of the 36 databases contained at least 1 included reference at the time of searching (Figure 1 online): MEDLINE contained the highest number of included references (30/ 44, 68%), followed by Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI; 26/44, 59%) and AgeLine (25/44, 57%). Four databases contained 1 unique reference, each at the time of the original searches for the systematic review: AgeLine, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and SSCI. Three included references (1 book chapter, 1 conference abstract, 1 dissertation) were only available by checking references or contacting authors. The minimum combination of sources that contained all the included references was AgeLine, EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), MEDLINE, PsycINFO, SSCI, reference checking, and author contact.

Where were the references identified by the search strategies used in the original review? In the majority of the databases, the search strategies failed to retrieve all the included references available in that database (Figure 1 online), due to the bibliographic details containing:

no carer terms (ten records)

no respite terms (six records)

ambiguous carers terms (two records) (e.g., “families of the aged”)

ambiguous respite care terms (five records) (e.g., “practical and emotional help” or “support strategies”)

Fourteen bibliographic records contained no abstract, and two a limited abstract. Unique references (i.e., items available in only one of the searched resources) were identified by the search strategies used in the systematic review in four databases: AgeLine (two records), EMBASE (two records), PsycINFO (two records), and SSCI (one record).

The minimum combination of sources to retrieve all the included references with the search strategies used in the systematic review was the same combination of sources that contained all the included references: AgeLine, EMBASE, HMIC, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, SSCI, reference checking, and contacting authors.

Search strategy precision

The precision of the search strategies in the majority of the databases was very low (Table 3). The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) had the highest precision (5.17%), meaning that approximately 19 records would need to be read to retrieve 1 included reference. Specialized databases relating to the elderly had low precision (AgeInfo, 1.05%; AgeLine, 0.98%).

Sources of included randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Where were the RCTs available? Over half of the included references were RCTs (25/44, 57%). Fifteen of the 36 databases contained as least 1 included RCT at the time of searching (Figure 2 online). MEDLINE contained the greatest number of included RCTs (20/25), followed by AgeLine (18/25) and CENTRAL (18/25) (Figure 2 online). Unique included RCTs (i.e., RCTs only available in 1 resource) were available from searching AgeLine, by checking references, and by contacting authors.

The minimum combinations of sources that contained all the included RCTs were AgeLine, reference checking, and contacting authors plus:

a. MEDLINE and EMBASE

b. CENTRAL and MEDLINE

c. CENTRAL and EMBASE

Where were the RCTs identified? In most databases, the search strategies failed to retrieve all the included RCTs available in that database (Figure 2 online). The minimum necessary combination of sources to retrieve all the included RCTs with the search strategies used in the systematic review was the same combination as those that contained all the included references: AgeLine, reference checking, and contacting authors plus:

a. MEDLINE and EMBASE

b. CENTRAL and MEDLINE

c. CENTRAL and EMBASE

The combination of AgeLine, CENTRAL, and EMBASE plus reference checking and contacting authors had the highest precision and 100% sensitivity.

DISCUSSION

Databases

Post-hoc analysis demonstrated that complete retrieval of included references for a systematic review on respite care could be achieved by searching six databases plus reference checking and contacting authors. The six databases that needed to be searched to identify all the included references for this systematic review were two first-line health databases (EMBASE, MEDLINE), three specialist databases (AgeLine, HMIC, and PsycINFO), and a social science database (SSCI). This range of databases probably reflects the multidisciplinary nature of the topic, which is typical of reviews of social care [2, 11]. These results also reinforced the results of other studies outside the traditional medical arena that have indicated the value of searching more than one or two databases [6, 13–15].

The minimum number of sources needed to retrieve all included RCTs was easier to predict: CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE are suggested as the best sources [16–18]. Searches beyond these databases are sometimes recommended [15, 19–21], and the value of searching specialist databases dependent on the topic has also been emphasized (e.g., PsycINFO for mental health topics [4], the Transport database for transport topics [8], AgeInfo for home care services for older people [1], and CINAHL for nurse related topics [22]). These results were similar to those of Bayliss et al., who found that the minimum combination of databases to identify RCTs for a psychological intervention was a specialist database (PsycINFO) plus CENTRAL, EMBASE, and MEDLINE [4].

The usefulness of reference checking, contacting experts, and other more serendipitous means of identifying relevant information has often been emphasized [20, 23–25] and is supported by the current retrospective analysis: both reference checking and contacting authors produced at least one unique reference included in the review.

Search strategies

Despite using a very broad search strategy, with many synonyms for “carer” and “respite” terms and no restrictions with “frail” or “elderly” terms or by study design, most of the searches did not retrieve all the available included references, demonstrating the variability in the use of terms for social care concepts. It also indicates the value of including abstracts in citation records and appropriate indexing: many of the records that were missed by the database searches for the systematic review did not have an abstract and/or appropriate indexing terms.

Limitations

The current study is limited to one systematic review, so generalizability of the results has not been tested on other systematic reviews. In addition, the analysis did not take into consideration the impact on the results of the systematic review if some of the studies had not been identified (e.g., if only MEDLINE had been searched, would the review conclude differently on the effectiveness of respite care?).

To accurately predict the ideal combination of databases identified in the current retrospective analysis would be virtually impossible and is unlikely to be generalizable to other areas of social care. However, analyses of other systematic reviews in similar topic areas are still recommended as, although they are unlikely to uncover a definitive set of databases to search for evidence in systematic reviews of social care, they may provide a useful insight into which databases frequently contain or rarely contain included references, allowing for more efficient use of searching effort.

CONCLUSION

It is widely accepted that search strategies for systematic reviews of social care interventions should contain a range of synonyms and few limits to increase sensitivity [2]. The current study demonstrates, however, that information professionals need to be aware that even sensitive search strategies with a broad range of synonyms may not identify all the references meeting the inclusion criteria that are available in a particular database. Searching a number of different sources is likely one key way to compensate for these issues.

This paper also demonstrates that a systematic review of a social care topic may require a range of databases covering different disciplines. Reference checking and contacting authors are also valuable sources of unique relevant references and provides materials not available through the use of databases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Hilary Arksey and Caroline Glendinning from the Social Policy Research Unit, University of York; Helen Weatherly and Michael Drummond from the Centre for Health Economics; University of York and Joy Adamson from the Department of Health Sciences, University of York, for their contributions to the original systematic review. The authors also thank Jane Burch, Julie Glanville, and Marie Westwood from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

FUNDING

The authors received funding from the UK Department of Health's National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment (NCCHTA) to carry out the systematic review on the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of different models of community-based respite care for frail older people and their carers. The opinions and conclusions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the UK National Health Service or Department of Health.

No funding was received for the retrospective analysis of the references included in this review.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This article has been approved for the Medical Library Association's Independent Reading Program <http://www.mlanet.org/education/irp/>.

Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 and Figures 1 and 2 are available with the online version of this journal.

REFERENCES

- Grayson L, Gomersall A. A difficult business: finding the evidence for social science reviews (working paper 19). London, UK: Economic and Social Research Council, UK Centre for Evidence Based Policy and Practice, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BJ, Dempster M, and Donnelly M. Hidden gems: systematically searching electronic databases for research publications for social work and social care. Br J Soc Work. 2003 Jun; 33(4):423–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss S, Dretzke J. Health technology assessment in social care: a case study of randomized controlled trial retrieval. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2006 Winter; 22(1):39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor MH. Social care: family and community support systems. Ann Amer Acad Pol Soc Sci. 1989 May; (503):99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Campbell Collaboration. The Campbell Collaboration, what helps? what harms? based on what evidence? [web document]. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research, 2007. [cited 15 Jun 2007]. <http://www.campbellcollaboration.org>. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver N, Williams JL, Weightman AL, Kitcher HN, Temple JM, Jones P, and Palmer S. Taking STOX: developing a cross disciplinary methodology for systematic reviews of research on the built environment and the health of the public. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002 Jan; 56(1):48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie D, Hamilton V, Egan M, and Petticrew M. Systematic reviews of health effects of social interventions: 1. finding the evidence: how far should you go? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005 Sep; 59(9):804–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomersall A. Finding the evidence: looking further afield. Evidence & Policy. 2005 May; 1(2):269–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mason A, Weatherly H, Spilsbury K, Golder S, Arksey H, Adamson J, Drummond M, and Glendinning C. A systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different models of community-based care for frail older people and their carers. Health Technol Assess. 2007 Apr; 11(15):1–157.iii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness (CRD report 4). 2nd ed. York, UK: University of York, National Health Service Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, Jackson K, Croucher K, Weatherly H, Golder S, Hare P, Newbronner E, and Baldwin S. Review of respite services and short-term breaks for carers for people with dementia. London, UK: National Health Service Service Delivery and Organisation, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brettle A, Long A. Comparison of bibliographic databases for information on the rehabilitation of people with severe mental illness. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001 Oct; 89(4):353–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews E, Edwards A, Barker J, Bloor M, Covey J, Hood K, Pill R, Russell I, Stott N, and Wilkinson C. Efficient literature searching in diffuse topics: lessons from a systematic review of research on communicating risk to patients in primary care. Health Libr Rev. 1999 Jun; 16(2):112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevinson C, Lawlor D. Searching multiple databases for systematic reviews: added value or diminishing returns? Complement Ther Med. 2004 Dec; 12(4):228–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Juni P, Bartlett C, Holenstein F, and Sterne J. How important are comprehensive literature searches and the assessment of trial quality in systematic reviews? empirical study. Health Technol Assess 2003;7(1):1–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royle P, Milne R. Literature searching for randomized controlled trials used in Cochrane reviews: rapid versus exhaustive searches. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003 Fall; 19(4):591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royle P, Bain L, and Waugh N. Sources of evidence for systematic reviews of interventions in diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005 Oct; 22(10):1386–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumley ET, Wiebe N, Cramer K, Klassen TP, and Hartling L. Which resources should be used to identify RCT/CCTs for systematic reviews: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol [serial online]. 2005;5:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoie I, Helmer D, Green CJ, and Kazanjian A. Beyond Medline: reducing bias through extended systematic review search. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003 Winter; 19(1):168–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betran A, Say L, Gulmezoglu A, Allen T, and Hampson L. Effectiveness of different databases in identifying studies for systematic reviews: experience from the WHO systematic review of maternal morbidity and mortality. BMC Med Res Methodol [serial online]. 2005;5:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subirana M, Sola I, Garcia JM, Gich I, and Urrutia G. A nursing qualitative systematic review required MEDLINE and CINAHL for study identification. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005 Jan; 58(1):20–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus RJ, Wilson S, Delaney BC, Fitzmaurice DA, Hyde CJ, Tobias RS, Jowett S, and Hobbs FD. Review of the usefulness of contacting other experts when conducting a literature search for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1998 Dec 5; 317(7172):1562–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmer D, Savoie I, Green C, and Kazanjian A. Evidence-based practice: extending the search to find material for the systematic review. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001 Oct; 89(4):346–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ. 2005 Nov 5; 331(7524):1064–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.