Abstract

There is an urgent need for the development of serodiagnostic approaches with improved sensitivity for patients with acute leptospirosis. Immunoblots were performed on 188 sera collected from 74 patients with laboratory-confirmed early leptospiral infection to detect immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to antigens pooled from 10 leptospiral strains prevalent in Thailand. Sera from patients with other febrile diseases served as controls. IgM reactivity to seven distinct antigens, with apparent molecular masses of 14 to 18, 19 to 23, 24 to 30, 32, 35/36, 37, and 41/42 kDa, was observed. The low-molecular-mass 14- to 18-kDa band was the most frequently detected antigen, being recognized in sera from 82.4% of patients during the first 3 days after the onset of symptoms. We evaluated the accuracy of the IgM immunoblot (IgM-IB) test by using reactivity to the 14- to 18-kDa band and/or at least two bands among the 19- to 23-, 24- to 30-, 32-, 35/36-, 37-, and 41/42-kDa antigens as the diagnostic criterion. The sensitivities of the IgM-IB test and the microscopic agglutination test (MAT) were 88.2% and 2.0%, respectively, with sera from patients 1 to 3 days after the onset of symptoms. In contrast, the IgM-IB test was positive with only 2/48 (4.2%) sera from patients with other febrile illnesses. The high sensitivity and specificity of the IgM-IB test for acute leptospirosis would provide greatly improved diagnostic accuracy for identification of patients who would benefit from early antibiotic intervention. In addition, the antigens identified by the IgM-IB test may serve as components of a rapid, accurate, point-of-care diagnostic test for early leptospirosis.

Leptospirosis is the most widespread zoonotic disease (45) and has emerged as an important public health problem, especially when heavy rainfall results in flooding in areas with poor housing and sewage infrastructure (6, 26, 41). Patients with leptospirosis develop high fever, sudden onset of headache, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and muscle pain, all of which are easily confused with symptoms of other febrile illnesses (17, 28). These nonspecific presenting symptoms frequently lead to misdiagnosis of leptospirosis as influenza, hepatitis, dengue fever, hantavirus infection, and other causes of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (2, 27, 47). Untreated patients are at risk for life-threatening multiorgan system complications of severe leptospirosis, including renal failure, liver damage, massive pulmonary hemorrhage, cardiac arrhythmia, and circulatory collapse (28, 38). Timely and accurate diagnosis of acute leptospirosis would result in earlier administration of antibiotics, which are potentially effective in mitigating the adverse consequences of leptospiral infection (20, 39, 42).

A number of serological methods have been described for the laboratory diagnosis of leptospirosis, including the microscopic agglutination test (MAT) (11), macroscopic agglutination (7, 44), indirect hemagglutination (29), microcapsule agglutination (4, 5), and ELISA (14, 43). However, the sensitivities of reported serologic tests with acceptable levels of specificity are ≤72% for acute leptospirosis (31). The one exception is the recent report of 81% sensitivity during the first 7 days of illness for an immunoblot assay to detect antibodies to recombinant LigB (12). The MAT remains the most widely used standard reference technique (1). The MAT is a complex and technically demanding method, requiring knowledge of the prevalent strains causing infection in a particular region, maintenance of a large panel of leptospiral cultures for testing with sera, and proficiency testing to provide training and quality control (10). Commercial ELISA kits employ antigens derived from a nonpathogenic strain (e.g., Leptospira biflexa strain Patoc I) and have generally been found to have lower sensitivity than the MAT because the ELISA antigens do not support detection of all infecting serovars (1). Because of the problems with currently available serologic approaches, we have been interested in identifying leptospiral antigens with higher sensitivity for detection of antileptospiral antibodies during the acute phase of infection. Previous immunoblot studies identified a number of potentially useful leptospiral antigens in clinical leptospirosis sera (19, 32, 36). For this reason, we evaluated the analytic validity of an immunoglobulin M immunoblot (IgM-IB) assay for the diagnosis of acute leptospirosis. Using a mixture of local blood culture isolates (34, 40, 46), we identified several low-molecular-weight antigens that were recognized by antibodies in a high percentage of sera from patients with early disease. Inclusion of these low-molecular-weight antigens in the diagnostic criteria resulted in an IgM-IB test with superior sensitivity for diagnosis of acute leptospirosis. This is the first report that we are aware of describing >85% diagnostic sensitivity during the first week of illness due to leptospirosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimens.

Sera were obtained from patients with acute febrile illness on the day of first visit, day of discharge, and 14 days after the first visit to Loei Provincial Hospital during the period from July through October 2002 (35). A total of 188 serum samples were obtained from 74 patients with leptospirosis confirmed by either culture isolation, MAT, or both. Leptospiral cultivation was performed as described previously (17). Control sera were obtained from 25 healthy blood donors and 12 patients each with dengue hemorrhagic fever, melioidosis, viral hepatitis, and malaria. All study participants provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Medical Ethics Committee at Ramathibodi Hospital, Thailand.

Preparation of antigens and immunoblotting.

As previously described (33), immunoblot antigens consisted of 10 leptospira, the same strains as those used in the MAT (Table 1). Leptospires were grown to mid-logarithmic phase in 7 days at 29°C in liquid Ellinghausen-McCullough-Johnson-Harris medium (25). Equal numbers of all 10 leptospiral strains were mixed and solubilized in standard Laemmli buffer composed of 62.5 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 6.8), 10% glycerol, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate and then heated to 100°C for 5 min. After removal of insoluble material by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min, samples derived from 0.5 × 107 to 1.0 × 107 cells were loaded onto lanes of a 12.5% acrylamide gel. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed in a Hoefer Mighty Small II minigel apparatus (Amersham Biosciences, San Francisco, CA), using a constant voltage of 200 V for 1 h. The resolved antigens were transferred onto a 0.45-μm-thick polyvinylidene difluoride membrane by using a semidry system (TE70; Amersham Biosciences) with a constant current density of 1.5 mA/cm2 for 60 min. Rabbit antisera to LipL21, LipL32, LipL41, and GroEL were prepared as previously described (13, 21, 23, 37).

TABLE 1.

Leptospiral strains used for immunoblot and MAT studies

| Strain no. | Serogroup | Serovar | Strain | Leptospira species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Australis | Australis | Ballico | L. interrogans |

| 2 | Australis | Bratislava | Jez Bratislava | L. interrogans |

| 3 | Autumnalis | Autumnalis | Akiyami A | L. interrogans |

| 4 | Bataviae | Bataviae | Swart | L. interrogans |

| 5 | Canicola | Canicola | Hond Utrecht IV | L. interrogans |

| 6 | Icterohaemorrhagiae | Copenhageni | M20 | L. interrogans |

| 7 | Djasiman | Djasiman | Djasiman | L. interrogans |

| 8 | Grippotyphosa | Grippotyphosa | Moskva V | L. kirscheneri |

| 9 | Hebdomadis | Hebdomadis | Hebdomadis | L. interrogans |

| 10 | Sejroe | Sejroe | M84 | L. borgpetersenii |

IgM-IB test.

Detection of antibodies to leptospires was determined by immunoblotting as previously described (33). Briefly, the blotted membrane was washed three times (5 min each) with 100 mM phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (PBST) and incubated for 60 min with either control sera (1:25 dilution), acute-phase sera (obtained on the first day of visit) (1:25 dilution), or convalescent-phase sera (obtained ≥2 weeks after first visit) (1:250 dilution in 2% skim milk in PBST). The membrane was washed three times with PBST and incubated for 60 min with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-human IgM (1:1,000 dilution; Dakopatt, Copenhagen, Denmark). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using H2O2 and 3,3-diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as the substrate. Molecular masses of the immunoreactive bands were estimated using Amersham Bioscience standard protein markers.

MAT.

MAT was performed as previously described (11). Briefly, 50 μl of each serum sample was mixed with an equal volume of a suspension of live leptospires (approximately 2 × 108 leptospires/ml) in a 96-well microtiter plate. After incubation for 2 hours at room temperature, agglutination was examined by dark-field microscopy (Olympus DP70 BX51; Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan). Wells with >50% agglutination were considered positive. The most dilute titer with positive agglutination was reported.

RESULTS

Leptospiral antigens for IgM recognition during natural infection.

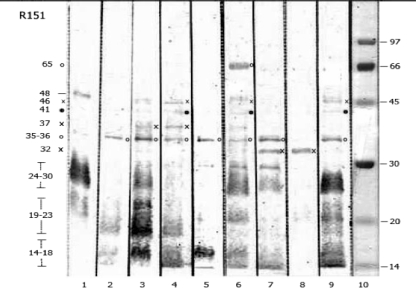

The IgM recognition profiles of various leptospiral antigens were evaluated in 188 acute- and convalescent-phase sera. IgM antibodies predominantly recognized antigens in the molecular mass range of 14 to 69 kDa. Eleven immunoreactive bands of 14- to 18-, 19- to 23-, 24- to 30-, 32-, 35/36-, 37-, 41/42-, 45-, 48-, 54-, and 64/69-kDa proteins were observed (Fig. 1). Antigens in the 14- to 18-, 19- to 23-, and 24- to 30-kDa ranges typically appeared as diffuse rather than discrete bands. IgM reactivity to the 35/36-kDa antigen appeared either as a single 35-kDa band or as a 35/36-kDa doublet. The 41/42-kDa antigen complex contained bands of 41 and 42 kDa that were difficult to discriminate.

FIG. 1.

IgM reactivities of sera from patients with leptospirosis. Representative immunoblots are shown in lanes 1 to 9. Symbols (×, ○, and •) indicate the locations of reactive antigen bands in the blots and their sizes on the left side of the figure. Lane 10 shows the locations of molecular size standards.

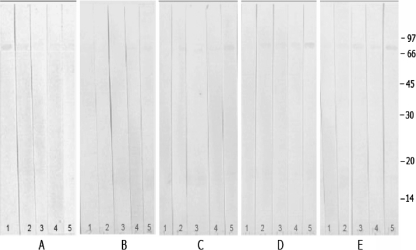

The specificity of seroreactivity with the various leptospirosis antigens was determined using sera from 25 blood donors and each of 12 patients with melioidosis, malaria, hepatitis, and dengue hemorrhagic fever (Fig. 2). Only one 64-kDa band was recognized by sera in the control blood donor group, whereas five immunoreactive bands, of 14 to 18, 19 to 23, 32, 54, and 64/69 kDa, were observed in sera from control febrile illness patients.

FIG. 2.

Representative immunoblots for sera from patients without leptospirosis. Sera were obtained from five patients each who were healthy blood donors (A) or had fever due to melioidosis (B), dengue fever (C), hepatitis (D), or malaria (E). The locations of molecular size standards are shown in kilodaltons on the right.

The frequencies of IgM-IB antibody reactivity to leptospiral antigens were determined with convalescent-phase sera of 74 leptospirosis patients and compared with the blood donor and febrile illness control groups (Table 2). The two smallest antigens, with apparent molecular masses of 14 to 18 and 19 to 23 kDa, were recognized most frequently in sera from leptospirosis patients. Control sera from patients with febrile illness reacted frequently with the 54- and 64/69-kDa antigens. IgM reactivity to the 24- to 30-, 32-, 35/36-, 37-, 41/42-, 45-, and 48-kDa antigens occurred exclusively in sera from patients with leptospirosis.

TABLE 2.

Percentages of cases showing IgM-IB reactivity to leptospiral antigen bands among leptospirosis patients, febrile individuals without leptospirosis, and healthy blood donors

| Leptospiral antigen (kDa) | % of cases (no. of patients) with positive IgM reactivity to leptospiral protein bands

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy donorsa (n = 25) | Leptospirosis patientsb (n = 74) | Nonleptospirosis patientsc (n = 48) | |

| 64/69 | 40 (10) | 67.6 (50) | 50.0 (24) |

| 54 | 0 | 10.8 (8) | 22.9 (11) |

| 48 | 0 | 9.5 (7) | 0.0 |

| 45 | 0 | 16.2 (12) | 0.0 |

| 41/42 | 0 | 45.9 (34) | 0.0 |

| 37 | 0 | 29.7 (22) | 0.0 |

| 35/36 | 0 | 31.1 (23) | 0.0 |

| 32 | 0 | 66.2 (49) | 4.2 (2)e |

| 24-30d | 0 | 59.5 (41) | 0.0 |

| 19-23d | 0 | 90.5 (67) | 4.2 (2)e |

| 14-18d | 0 | 91.9 (68) | 4.2 (2)e |

Healthy blood donors from Ramathibodi Blood Bank.

Confirmed by isolation and/or MAT results of seroconversion or a single titer of ≥400.

Twelve individuals each with melioidosis, dengue, hepatitis, and malaria, which represent nonleptospirosis control groups.

Mostly diffuse bands.

Found in two malaria cases.

Immunoreactive bands during acute and convalescent phases of leptospirosis.

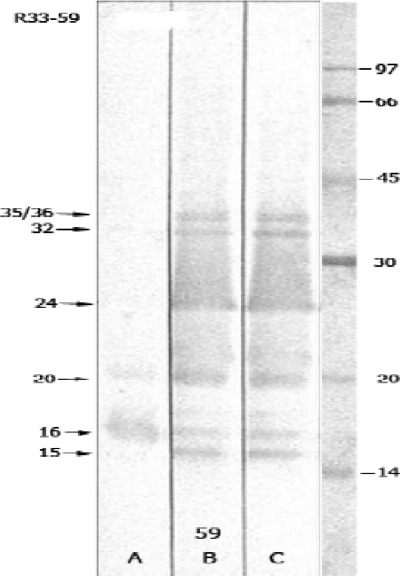

Serum samples collected at various times after the onset of symptoms from 74 patients with leptospirosis confirmed by either MAT, cultivation, or both (Table 3) were analyzed by IgM-IB. Overall, 62.2% (46/74 cases) and 75.7% (56/74 cases) of representative leptospirosis cases were positive by cultivation and microscopic agglutination methods, respectively. Figure 3 shows the evolution of IgM immunoblot reactivity in a single representative patient. In general, antibody reactivity to most bands increased during the acute phase (days 1 to 12) of leptospirosis. Exceptions to this pattern were the 35/36- and 37-kDa bands, which were variable and never exceeded 40% reactivity during the acute phase. Interestingly, a high frequency of antibodies to the low-molecular-mass (14 to 18 and 19 to 23 kDa) antigens was observed in sera from the earliest stages of illness.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of IgM reactive immunoblot bands in 188 serum samples collected from 74 patients with laboratory-confirmed cases of leptospirosis, compared with conventional MAT and culture resultsb

| Antigen band(s) (kDa) | % of serum samples with IgM reactivity in days after fever onset

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 3 (n = 51) | 4 to 6 (n = 41) | 7 to 9 (n = 22) | 10 to 12 (n = 8) | 13 to 15 (n = 10) | 16 to 18 (n = 45) | 19 to 28 (n = 11) | |

| 41/42 | 27.5 | 31.7 | 31.8 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 26.7 | 54.5 |

| 37 | 21.6 | 9.8 | 36.4 | 25.0 | 30.0 | 17.8 | 27.3 |

| 35/36 | 23.5 | 22.0 | 31.8 | 12.5 | 40.0 | 26.7 | 36.4 |

| 32 | 47.1 | 51.2 | 59.1 | 87.5 | 80.0 | 75.6 | 63.6 |

| 24-30a | 31.4 | 39.0 | 54.5 | 75.0 | 30.0 | 66.7 | 63.6 |

| 19-23a | 76.5 | 73.2 | 81.8 | 100.0 | 80.0 | 77.8 | 100.0 |

| 14-18a | 82.4 | 85.4 | 81.8 | 100.0 | 80.0 | 82.2 | 100.0 |

| 14-18 and/or at least two in 19-42 region | 88.2 | 90.2 | 90.9 | 100.0 | 90.0 | 84.4 | 100.0 |

Diffuse banding was determined by a single serum sample, with immunoreactive bands commonly detected in the range of 14 to 18, 19 to 23, and 24 to 30 kDa.

For MAT, a single serum with a titer of ≥400 was considered positive. With MAT, the percentages of serum samples with IgM reactivity 1 to 3, 4 to 6, 7 to 9, 10 to 12, 13 to 15, 16 to 18, and 19 to 28 days after the onset of fever were 2.0, 22.0, 68.2, 87.5, 30.0, 75.6, and 63.6%, respectively. For culture, the percentages of samples with leptospire positivity at 1 to 3, 4 to 6, 7 to 9, 10 to 12, and 13 to 15 days after the onset of fever were 45.9% (34/74 samples), 10.8% (8/74 samples), 2.7% (2/74 samples), 1.4% (1/74 samples), and 1.4% (1/74 samples), respectively.

FIG. 3.

Evolution of IgM immunoblot reactivity during leptospirosis. Lanes A, B, and C are immunoblots performed using sera obtained from a single patient 6, 11, and 21 days, respectively, after the onset of fever. The locations of immunoreactive bands are shown on the left. The locations of molecular size standards are shown in kilodaltons on the right.

Diagnostic criteria for IgM-IB test comparison with MAT.

Analysis of the sensitivity and specificity of bands recognized in the IgM-IB test led to the following diagnostic criteria: reactivity with the 14- to 18-kDa antigen and/or at least two positive bands from among the 19- to 23-, 24- to 30-, 32-, 35/36-, 37-, and 41/42-kDa antigens. Using these criteria, the IgM-IB assay and MAT were compared for all 188 sera from 74 patients with confirmed leptospirosis. As shown in Table 4, the IgM-IB assay was considerably more sensitive than the MAT during the first week after the onset of symptoms. The seropositivity rates for the IgM-IB test versus the MAT were 88.2% versus 2.0% and 90.2% versus 22.0% during days 1 to 3 and days 4 to 6 after the onset of symptoms. MAT sensitivity increased after the first week but did not exceed the IgM-IB seropositive rates for any time period during the first 28 days after the onset of symptoms. Among 188 tested samples, only 76 specimens (40.4%) were positive (titers of ≥400) by MAT, compared to 167 (88.8%) specimens which were positive by IgM-IB.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of IgM immunoblot and MAT results for 188 serum samples from 74 patients with confirmed cases of leptospirosis

| Days after onset (no. of samples) | % (no.) of samples positive

|

No. of samples with titer of:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM-IBa | MATb | ≤100 | 200 | 400 | 800 | 1,600 | ≥3,200 | |

| 1 to 3 (51) | 88.2 (45) | 2.0 (1) | 47 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 to 6 (41) | 90.2 (37) | 22.0 (9) | 23 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| 7 to 9 (22) | 90.9 (20) | 68.2 (15) | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| 10 to 12 (8) | 100.0 (8) | 87.5 (7) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 13 to 15 (10) | 90.0 (9) | 30.0 (3) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 16 to 18 (45) | 84.4 (38) | 75.6 (34) | 5 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 19 |

| 19 to 21 (9) | 100.0 (9) | 66.7 (6) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 24 to 28 (2) | 100.0 (2) | 50.0 (1) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal for days 1 to 6 (92) | 89.1 (82) | 10.9 (10) | 70 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Subtotal for days 7 to 15 (40) | 92.5 (36) | 62.5 (25) | 9 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 13 |

| Subtotal for days 16 to 28 (56) | 87.5 (49) | 73.2 (41) | 7 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 22 |

| Total (188) | 88.8 (167) | 40.4 (76) | 86 | 26 | 17 | 10 | 14 | 35 |

For the IgM-IB test, results were considered positive if bands were detected in the range of 14 to 18 kDa and/or two bands were detected among the following regions: 19 to 23, 24 to 30, 32, 35/36, 37, and 41/42 kDa.

A single serum with a titer of ≥400 was considered positive.

Evaluation of IgM-IB test accuracy.

The accuracy of the IgM-IB method was evaluated with sera from 122 patients with acute febrile illness. Table 5 shows the IgM-IB results for serum samples from 74 patients with leptospirosis and 48 control patients. The IgM-IB test was positive in 68 of 74 leptospirosis cases, yielding a sensitivity of 91.9%. Only 2 of 48 sera from nonleptospirosis controls were positive, yielding a specificity of 95.8%. For this selected patient population, the positive and negative predictive values were 97% and 88.5%, respectively.

TABLE 5.

Specificity and sensitivity of IgM-IB for 74 cases of leptospirosis and 48 cases of febrile illness not due to leptospirosisc

| IgM-IB result | No. of confirmed leptospirosis casesa

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positiveb | 68 | 2 | 70 |

| Negative | 6 | 46 | 52 |

| Total | 74 | 48 | 122 |

Leptospirosis cases confirmed by MAT and/or cultivation.

Band recognition of leptospirosis, including the 14- to 18-kDa band and/or two other reactive bands among the 19- to 41/42-kDa bands.

The sensitivity of IgM-IB was 91.9%, the specificity was 95.8%, the positive predictive value was 97%, the negative predictive value was 88.5%, and the accuracy was 93.4%.

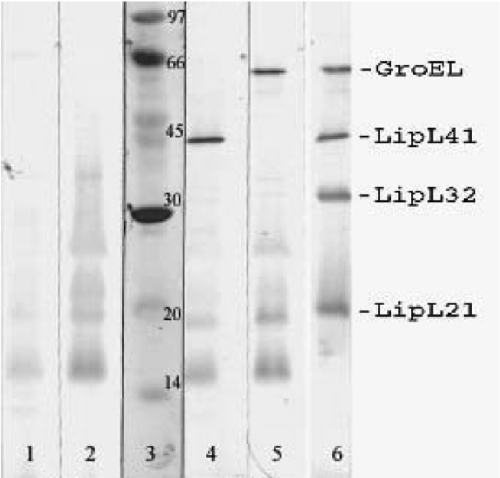

Identification of antigens recognized by the IgM-IB test.

Additional immunoblot studies were performed to determine the identities of some of the antigens recognized by patient sera in the IgM-IB test. As shown in Fig. 4, the locations of several lipoproteins and the heat shock protein GroEL were determined using rabbit polyclonal antisera specific for these proteins. By comparison with immunoblots performed using patient sera, it was determined that LipL21, LipL32, LipL41, and GroEL account, at least in part, for the 24-to 30-, 32-, 41-, and 64/69-kDa antigens, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Reactivities of sera from leptospirosis patients with protein antigens. Sera were obtained from patients 2 days (lane 1), 16 days (lane 2), 6 days (lane 4), and 11 days (lane 5) after the onset of leptospirosis. Lane 3 shows the locations of molecular size standards. Lane 6 is an immunoblot of leptospiral antigens probed with antisera to leptospiral proteins GroEL, LipL41, LipL32, and LipL21.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe an IgM-IB method with high sensitivity for detection of leptospiral antibodies in patients during the first several days after the onset of symptoms. This approach has important advantages over existing diagnostic techniques. Leptospiral isolation in artificial culture medium remains the definitive method for the diagnosis of leptospirosis. However, cultivation is restricted to reference laboratories and takes too much time because of the slow growth of leptospires in artificial media (17). Among serologic techniques, MAT is the reference method for routine laboratory use. Unfortunately, MAT does not achieve high sensitivity for detection of circulating antibodies until 8 to 10 days after the onset of illness (3, 7, 14). Alternative serologic approaches developed to date also have poor sensitivity at the time when patients present to health care providers with symptoms of early infection (31). For these reasons, we evaluated whether immunoblotting is able to detect antibodies present in the sera of patients with acute leptospirosis. The IgM-IB analyses showed that seven distinctive groups of leptospiral antigens, with molecular masses of 14 to 18, 19 to 23, 24 to 30, 32, 35/36, 37, and 41/42 kDa, were useful as antigens for serodiagnosis of acute leptospirosis. During the acute and subacute phases of illness, IgM reactivities against the 14- to 18- and 19- to 21-kDa antigens were observed with the highest frequencies (88.2 to 100%), illustrating their usefulness in early diagnosis.

The diffuse banding pattern of the three antigens with apparent molecular masses of 14 to 18, 19 to 23, and 24 to 30 kDa is characteristic of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The carbohydrate component of these LPS antigens was previously demonstrated by periodate silver staining of gels containing leptospiral outer membranes (24). The studies we report here expand on earlier work to define the LPS and protein antigens recognized by the humoral immune response to leptospirosis (8, 9). Chapman et al. (8) compared immunoblots for acute- and convalescent-phase sera from a small number of patients infected with serovar Hardjo and observed a high frequency of IgM reactivity to an LPS antigen with an apparent molecular mass of 28 kDa. Immunoblot reactivity to LPS was confirmed by Ribeiro et al. (36), who described a proteinase K-resistant, diffuse band of 14.8 to 22 kDa recognized by IgMs from a large percentage of sera from patients with leptospirosis. The 14.8- to 22-kDa antigen described by Ribeiro et al. (36) may reflect a combination of the 14- to 18- and 19- to 23-kDa antigens described in our study. We were able to distinguish between reactivities to the 14- to 18- and 19- to 23-kDa antigens and found a slightly higher seroreactivity rate for the smaller antigen, particularly during the first 6 days after the onset of symptoms.

The agglutination of leptospires by clinical sera, which is the basis for the MAT, is thought to be mediated by LPS-specific antibodies (19). In this regard, it is interesting that only 2% of sera obtained within 3 days after the onset of symptoms were positive by MAT, while 82.4% and 76.5% of sera were reactive with the 14- to 18- and 19- to 23-kDa LPS antigens, respectively. At least two explanations for this discrepancy are possible. One possibility is that immunoblotting is a more sensitive method of antibody detection than the MAT, that is, a higher titer of LPS antibodies is required for agglutination of leptospires in the MAT than that required for band recognition by immunoblotting. A second possibility is that the larger, 24- to 30-kDa LPS antigen, not the smaller, 14- to 18- and 19- to 23-kDa LPS antigens, is the target of agglutinating antibodies. The latter explanation has biological plausibility in that the larger LPS antigen is likely to extend further from the outer membrane and to be more accessible to antibodies that cross-link organisms, which is required for agglutination to occur.

An important difference between our approach and earlier serodiagnostic studies is our use of a mixture of relevant leptospiral strains in the preparation of the immunoblot antigens, an important consideration in looking at antibody reactivity to LPS antigens in sera from patients with potential exposure to a diverse population of leptospiral serovars. During the planning phase of our study, immunoblot studies had suggested that combining 10 leptospiral serovars might be of benefit in the diagnosis of leptospirosis (33). Serogroup-specific antibody reactivity with LPS is typically reflected by the presence bands in the 19- to 30-kDa size range (15). In particular, serovar Bratislava was included in the pool of antigens used in the current study because of prior MAT results using sera from the same study participants (34).

Previously, Guerreiro et al. (19) provided a detailed description of the protein antigens recognized by acute- and convalescent-phase sera from leptospirosis patients. The percentages of sera reacting with various protein antigens reported by Guerreiro et al. are similar to what we observed. For example, the p32 antigen was recognized by 37% and 84% of acute- and convalescent-phase sera, respectively, and only 5% of healthy community controls in the study by Guerreiro et al. (19). In comparison, we observed positive reactions to the p32 antigen in 47.1 and 87.5% of sera from patients in the early acute phase (1 to 3 days after onset) and the late stage (10 to 12 days after onset) of leptospirosis, respectively, while none of the sera from blood donors recognized the p32 antigen. The p32 antigen was identified as LipL32 by two-dimensional immunoblotting by Guerreiro et al., and our studies confirm that conclusion. The p41/42 antigen appears to be composed of at least two proteins, one of which is the outer membrane lipoprotein LipL41 (37) and the other of which is a 42-kDa inner membrane protein (19). A 45.9% IgM reaction was found, similar to the reaction of 41.8% in an earlier study (32). Other proteins that appear to be recognized by antibodies in sera from leptospirosis patients include the outer membrane lipoproteins LipL21 and LipL46, the 35- to 36-kDa endoflagellar proteins, and the heat shock protein GroEL (8, 13, 19, 21, 30, 48).

The high degree of sequence conservation of some leptospiral proteins is a potential serodiagnostic advantage compared to the more variable LPS antigens. For example, LipL32 has been shown to have 99% amino acid sequence identity across a broad range of leptospiral species and strains, compared to 95% and 91% sequence identity for LipL41 and OmpL1, respectively (22). Purified recombinant proteins are also relatively easy to prepare compared to leptospiral LPS. When various recombinant protein antigens were examined by ELISA for their utility in serodiagnosis of leptospirosis, LipL32 had the highest sensitivity and specificity (18). Although the LipL32 ELISA had high sensitivity and specificity with convalescent-phase sera, it performed poorly with acute-phase sera, emphasizing the need to identify new antigens and approaches with the potential for improved serodiagnostic sensitivity for detection of early leptospirosis.

A novel aspect of our study was the examination of the serodiagnostic utility of proteins in combination with LPS antigens. The combination of protein and LPS bands, especially the p14-18 antigen, increased the sensitivity during early infection. The sensitivity of the combination of p14-18 and/or p19-41/42 increased from 82.4% to 88.2%, 85.4% to 90.2%, 81.8% to 90.9%, and 80.0 to 90.0% at 1 to 3, 4 to 6, 7 to 9, and 13 to 15 days after onset, respectively. Overall, a high proportion of IgM (82.4%) to the low-molecular-mass antigens (14 to 18 kDa) of combined pathogenic Leptospira spp. was detectable at the very early stage of the disease, within 3 days, compared with 48% positivity of the IgM response to LPS (13 to 21 and 28 kDa) from Leptospira biflexa in leptospiral uveitis patients (35) and 32.6% positivity for the leptospiral proteins p14 and p25 in acute-phase sera in a previous report (32). This came from an appropriate use of the detection antigens. Our IgM-IB test appears to be highly specific for leptospiral infection. In fact, it is possible that the 4.2% IgM seropositivity in the malaria group is due to coinfection or dual infection with malaria and leptospirosis, as reported elsewhere (16).

In summary, the combination of p14-18 and/or at least two bands for the 19- to 23-, 24- to 30-, 32-, 35/36-, 37-, and 41/42-kDa antigens has been detected with high degrees of sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy (91.9, 95.8, and 93.4%, respectively) by IgM-IB. This laboratory-based method will be modified in the future for field diagnosis of Leptospira infection in larger populations or during outbreaks of leptospirosis. Thus, further characterization of the 14- to 18-kDa antigen may help to lead to the development of improved rapid serodiagnostic methods when used in combination with other LPS or protein antigens.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Albert I. Ko and Visith Thongboonkerd for their useful comments. We thank Oranard Wattanawong and the staff of the Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Kannika Niwatayakul of Loei Provincial Hospital, Thailand, and Apichat Pradermwong and Kanjana Sirisidth of Mahidol University.

This study was supported by grants from the Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. D.A.H. was supported by VA Medical Research funds and by NIH/NIAID grant AI-34431.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 January 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad, S. N., S. Shah, and F. M. Ahmad. 2005. Laboratory diagnosis of leptospirosis. J. Postgrad. Med. 51:195-200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoniadis, A., S. Alexiou-Daniel, L. Finadin, and E. F. K. Bautz. 1995. Comparison of the clinical and serologic diagnosis of haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and leptospirosis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 8:228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appassakij, H., K. Silpapojakul, R. Wansit, and J. Woodtayakorn. 1995. Evaluation of the immunofluorescent antibody test for the diagnosis of human leptospirosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 52:340-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arimitsu, Y., S. Kobayashi, K. Akama, and T. Matuhasi. 1982. Development of a simple serological method for diagnosing leptospirosis: a microcapsule agglutination test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 15:835-841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arimitsu, Y., K. Fukumura, and Y. Shintaki. 1989. Distribution of leptospirosis among stray dogs in the Okinawa Islands, Japan: comparison of the microcapsule and microscopic agglutination tests. Br. Vet. J. 145:473-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bharti, A. R., J. E. Nally, J. N. Ricaldi, M. A. Matthias, M. M. Diaz, M. A. Lovett, P. N. Levett, R. H. Gilman, M. R. Willig, E. Gotuzzo, and J. M. Vinetz. 2003. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3:757-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandão, A. P., E. D. da Silva Camargo, M. V. Silva, and R. V. Abrão. 1998. Macroscopic agglutination test for rapid diagnosis of human leptospirosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3138-3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman, A. J., B. Adler, and S. Faine. 1988. Antigens recognised by the human immune response to infection with Leptospira interrogans serovar hardjo. J. Med. Microbiol. 25:269-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman, A. J., C. O. Everard, S. Faine, and B. Adler. 1991. Antigens recognized by the human immune response to severe leptospirosis in Barbados. Epidemiol. Infect. 107:143-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chappel, R. J., M. Goris, M. F. Palmer, and R. A. Hartskeerl. 2004. Impact of proficiency testing on results of the microscopic agglutination test for diagnosis of leptospirosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5484-5488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole, J. R., Jr., C. R. Sulzer, and A. R. Pursell. 1973. Improved microtechnique for the leptospiral microscopic agglutination test. Appl. Microbiol. 25:976-980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croda, J., J. G. Ramos, J. Matsunaga, A. Queiroz, A. Homma, L. W. Riley, D. A. Haake, M. G. Reis, and A. I. Ko. 2007. Leptospiral immunoglobulin-like (Lig) proteins are a serodiagnostic marker for acute leptospirosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1528-1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullen, P. A., D. A. Haake, D. M. Bulach, R. L. Zuerner, and B. Adler. 2003. LipL21 is a novel surface-exposed lipoprotein of pathogenic Leptospira species. Infect. Immun. 71:2414-2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cumberland, P. C., C. O. R. Everard, and P. N. Levett. 1999. Assessment of the efficacy of the IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and the microscopic agglutination test (MAT) in the diagnosis of acute leptospirosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 61:731-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doungchawee, G., W. Sirawaraporn, A. I. Ko, S. Kongtim, P. Naigowit, and V. Thongboonkerd. 2007. Use of immunoblotting as an alternative method for serogrouping Leptospira. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:587-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis, R. D., M. M. Fukuda, P. McDaniel, K. Welch, A. Nisalak, C. K. Murray, M. R. Gray, N. Uthaimongkol, N. Buathong, S. Sriwichai, R. Phasuk, K. Yingyuen, C. Mathavarat, and R. S. Miller. 2006. Causes of fever in adults on the Thai-Myanmar border. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 74:108-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faine, S., B. Adler, C. Bolin, and P. Perolat. 1999. Leptospira and leptospirosis, 2nd ed. MedSci, Melbourne, Australia.

- 18.Flannery, B., D. Costa, F. P. Carvalho, H. Guerreiro, J. Matsunaga, E. D. Da Silva, A. G. P. Ferreira, L. W. Riley, M. G. Reis, D. A. Haake, and A. I. Ko. 2001. Evaluation of recombinant Leptospira antigen-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for the serodiagnosis of leptospirosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3303-3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerreiro, H., J. Croda, B. Flannery, M. Mazel, J. Matsunaga, M. G. Reis, P. N. Levett, A. I. Ko, and D. A. Haake. 2001. Leptospiral proteins recognized during the humoral immune response to leptospirosis in humans. Infect. Immun. 69:4958-4968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guidugli, F., A. A. Castro, and A. N. Atallah. 2000. Antibiotics for treating leptospirosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2:CD 001306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haake, D. A., G. Chao, R. L. Zuerner, J. K. Barnett, D. Barnett, M. Mazel, J. Matsunaga, P. N. Levett, and C. A. Bolin. 2000. The leptospiral major outer membrane protein LipL32 is a lipoprotein expressed during mammalian infection. Infect. Immun. 68:2276-2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haake, D. A., M. A. Suchard, M. M. Kelley, M. Dundoo, D. P. Alt, and R. L. Zuerner. 2004. Molecular evolution and mosaicism of leptospiral outer membrane proteins involve horizontal DNA transfer. J. Bacteriol. 186:2818-2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haake, D. A., and J. Matsunaga. 2002. Characterization of the leptospiral outer membrane and description of three novel leptospiral membrane proteins. Infect. Immun. 70:4936-4945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haake, D. A., E. M. Walker, D. R. Blanco, C. A. Bolin, J. N. Miller, and M. A. Lovett. 1991. Changes in the surface of Leptospira interrogans serovar Grippotyphosa during in vitro cultivation. Infect. Immun. 59:1131-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson, R. C., and V. G. Harris. 1967. Differentiation of pathogenic and saprophytic leptospires. I. Growth at low temperatures. J. Bacteriol. 94:27-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko, A. I., M. G. Reis, C. M. D. Ribeiro, W. D. Johnson, Jr., L. W. Riley, and the Salvador Leptospirosis Study Group. 1999. Urban epidemic of severe leptospirosis in Brazil. Lancet 354:820-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levett, P. N., S. L. Branch, and C. N. Edwards. 2000. Detection of dengue infection in patients investigated for leptospirosis in Barbados. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 62:112-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levett, P. N. 2001. Leptospirosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:296-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levett, P. N., and C. U. Whittington. 1998. Evaluation of the indirect hemagglutination assay for diagnosis of acute leptospirosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsunaga, J., K. Werneid, R. L. Zuerner, A. Frank, and D. A. Haake. 2006. LipL46 is a novel surface-exposed lipoprotein expressed during leptospiral dissemination in the mammalian host. Microbiology 152:3777-3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McBride, A. J., D. A. Athanazio, M. G. Reis, and A. I. Ko. 2005. Leptospirosis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18:376-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Natarajaseenivasan, K., P. Vijayachari, A. P. Sugunan, S. Sharma, and S. C. Sehgal. 2004. Leptospiral proteins expressed during acute and convalescent phases of human leptospirosis. Indian J. Med. Res. 120:151-159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niwetpathomwat, A., and G. Doungchawee. 2006. Western immunoblot analysis using a ten leptospira serovars combined antigen for serodiagnosis of leptospirosis. SEA J. Trop. Med. Pub. Health 37:309-311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niwetpathomwat, A., K. Niwatayakul, and G. Doungchawee. 2005. Surveillance of leptospirosis after flooding at Loei Province, Thailand by year 2002. SEA J. Trop. Med. Pub. Health 36(Suppl. 4):185-188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Priya, C. G., K. Bhavani, S. R. Rathinam, and V. R. Muthukkaruppan. 2003. Identification and evaluation of LPS antigen for serodiagnosis of uveitis associated with leptospirosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:667-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ribeiro, M. A., E. E. Sakata, M. V. Silva, E. D. Camargo, A. J. Vaz, and T. De Brito. 1992. Antigens involved in the human antibody response to natural infections with Leptospira interrogans serovar copenhageni. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 95:239-245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shang, E. S., T. A. Summers, and D. A. Haake. 1996. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding LipL41, a surface-exposed lipoprotein of pathogenic leptospiral species. Infect. Immun. 64:2322-2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sitprija, V., K. Losuwanrak, and T. Kanjanabuch. 2003. Leptospiral nephropathy. Semin. Nephrol. 23:42-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suputtamongkol, Y., K. Niwattayakul, C. Suttinont, K. Losuwanaluk, R. Limpaiboon, W. Chierakul, V. Wuthiekanun, S. Triengrim, M. Chenchittikul, and N. J. White. 2004. An open, randomized, controlled trial of penicillin, doxycycline, and cefotaxime for patients with severe leptospirosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:1417-1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tangkanakul, W., H. L. Smits, L. S. Jatanasen, and D. A. Ashford. 2005. Leptospirosis: an emerging health problem in Thailand. SEA J. Trop. Med. Public Health 36:281-288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vinetz, J. M. 2001. Leptospirosis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 14:527-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watt, G., L. P. Padre, M. L. Tuazon, C. Calubaquib, E. Santiago, C. P. Ranoa, and L. W. Laughlin. 1988. Placebo-controlled trial of intravenous penicillin for severe and late leptospirosis. Lancet i:433-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winslow, W. E., D. J. Merry, M. L. Pirc, and P. L. Devine. 1997. Evaluation of a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of immunoglobulin M antibody in diagnosis of human leptospiral infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1938-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolff, J. W., and H. J. Bohlander. 1966. Evaluation of Galton's macroscopic slide test for the serodiagnosis of leptospirosis in human serum samples. Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Trop. 46:123-133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization. 1999. Leptospirosis worldwide. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 74:237-242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wuthiekanun, V., N. Sirisukkarn, P. Daengsupa, P. Sakaraserane, A. Sangkakam, W. Chierakul, L. D. Smythe, M. L. Symonds, M. F. Dohnt, T. Andrew, A. T. Slack, N. P. Day, and S. J. Peacock. 2007. Clinical diagnosis and geographic distribution of leptospirosis, Thailand. EID 13:124-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zaki, S. R., and W. J. Shieh. 1995. Leptospirosis associated with outbreak of acute febrile illness and pulmonary haemorrhage, Nicaragua, 1996. Lancet 24:535-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zuerner, R. L., W. Knudtson, C. A. Bolin, and G. Trueba. 2001. Characterization of outer membrane and secreted proteins of Leptospira interrogans serovar pomona. Microb. Pathog. 10:311-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]