Abstract

The RNA polymerase II enzyme from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a complex of 12 subunits, Rpb1 to Rpb12. Crystal structures of the full complex show that the polymerase consists of two separable components, a 10-subunit core including the catalytic active site and a heterodimer of the Rpb4 and Rpb7 subunits. To characterize the role of the Rpb4/7 heterodimer during transcription in vivo, chromatin immunoprecipitation was used to examine an rpb4Δ strain for effects on the behavior of the core polymerase as well as recruitment of other protein factors involved in transcription. Rpb4/7 cross-links throughout transcribed regions. Loss of Rpb4 results in a reduction of RNA polymerase II levels near 3′ ends of multiple mRNA genes as well as a decreased association of 3′-end processing factors. Furthermore, loss of Rpb4 results in altered polyadenylation site usage at the RNA14 gene. Together, these results indicate that Rpb4 contributes to proper cotranscriptional 3′-end processing in vivo.

The synthesis of eukaryotic mRNA by RNA polymerase II (RNApII) is a multistep process involving initiation, elongation, and termination. During the transcription cycle, RNApII associates with many proteins involved in the regulation of these processes, including the basal transcription factors, coactivators, elongation factors, and factors involved in 3′-end formation and termination (6). This regulation of transcription by RNApII and its associated proteins is critical for gene expression.

The RNApII enzyme from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a complex of 12 subunits, Rpb1 to Rpb12, that can dissociate into a 10-subunit core and a heterodimer consisting of Rpb4 and Rpb7 (6). Rpb4 is not essential during optimal growth conditions, although the deletion strain grows very slowly (32). RNApII purified from an rpb4Δ strain lacks Rpb4 but also contains no detectable level of Rpb7 (8). It has been shown that Rpb7, a subunit that is essential for cell viability (22), can interact with polymerase independently of Rpb4, but this interaction is weak and can easily be detected only when Rpb7 is overexpressed (28). RNApII lacking Rpb4/7 is catalytically active for polymerization, but the heterodimer is required for promoter-dependent transcription in vitro (8).

Crystal structures show the location of the Rpb4/7 heterodimer in the context of the complete RNApII complex (2, 3). Rpb4 makes very little contact with the core subunits; the dimer is held primarily through contacts between Rpb7 and core subunits Rpb1 and Rpb6. Rpb4/7 is found near both the transcript-exit groove and the linker to the C-terminal domain (CTD) of Rpb1, a location that would allow for interactions with the nascent RNA transcript as well as protein factors involved in transcription regulation. In fact, Rpb7 contains a potential oligonucleotide-binding domain that faces the presumed RNA exit site (6) and has recently been shown to cross-link to the emerging RNA transcript (31).

Recent reports also indicate that the heterodimer can interact with several transcription factors. Rpb7 from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe physically interacts in vitro with Seb1, a homolog of the S. cerevisiae CTD-binding protein and termination factor Nrd1 (23). Rpb4 has also been shown to physically interact with Fcp1, a CTD phosphatase (10, 17). Both the capability of Rpb4/7 to interact with these factors and the proximity of the heterodimer to the CTD suggest that Rpb4/7 might play a role in the recruitment of some CTD-binding proteins to transcribing RNApII.

Because RPB4 is nonessential in S. cerevisiae, it is possible to examine the role of the Rpb4/7 heterodimer in vivo by using an rpb4Δ strain. Cells that lack RPB4 are both heat and cold sensitive and also grow more slowly than wild-type strains at permissive temperatures (∼24 to 30°C) (32). The sensitivity of rpb4Δ cells to high temperatures has been associated with a general RNApII transcription defect (20, 24). In an attempt to better understand the in vivo effects of Rpb4 loss on the transcribing polymerase, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to map the cross-linking patterns of polymerase and multiple associated factors along transcribed genes in both wild-type and rpb4Δ strains. Deletion of RPB4 results in decreased polymerase occupancy at the 3′ end of mRNA genes. Additionally, Rpb4 is required for the association of the 3′-end processing factors Rna14 and Rna15 with RNApII and 3′ ends of genes. Our results therefore indicate an in vivo role for Rpb4 in the coupling of transcription and mRNA 3′-end processing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

S. cerevisiae strains.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

ChIPs.

Cells were grown in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 1% Bacto peptone, 2% glucose) at 23°C to an optical density (600 nm) of 0.8. Formaldehyde cross-linking, chromatin preparation, and immunoprecipitation were performed as described previously (11, 15). TAP-tagged proteins were precipitated with immunoglobulin G (IgG)-agarose (Sigma-Aldrich). Rpb3 and Rpb4 immunoprecipitations were done with commercially available mouse monoclonal antibodies (Neoclone). The Rna15 antibody was a gift from C. Moore (Tufts Medical School). Immunoprecipitations of hemagglutinin-tagged proteins were done with monoclonal 12CA5 antibody (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). All oligonucleotide sequences used are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. PCR conditions for SNR13 ChIPs and ChIPs with results shown in Fig. 6 were described previously (19). For ADH1, PYK1, and PMA1 ChIPs with results shown in other figures, multiplex PCRs were done using a protocol developed by TaeSoo Kim (Harvard Medical School). PCR conditions were as follows: 60 s at 94°C, followed by 25 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 45 s at 72°C, followed by a final 2 min at 72°C.

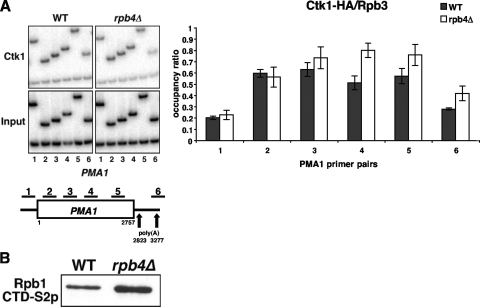

FIG. 6.

Loss of Rpb4 does not compromise serine 2 phosphorylation of the CTD. (A) Ctk1 kinase occupancy at the PMA1 gene is unaffected by loss of Rpb4. ChIP for Ctk1-hemagglutinin was performed with wild-type (WT) (YSB772) and rpb4Δ (YSB2225) strains. A schematic of PMA1 showing positions of PCR primers is shown below the gel. Quantification is shown in the right panel. Values represent the averages and standard errors from three independent experiments. (B) Loss of Rpb4 does not result in a decrease of cellular levels of serine 2-phosphorylated CTD. Whole-cell extracts from wild-type (YSB1140) and rpb4Δ (YSB1755) strains were analyzed by immunoblotting with H5 antibody (to detect serine 2-phosphorylated CTD [CTD-S2p]). The increase was similar to that in total Rpb1 levels (Fig. 1 and data not shown).

Protein analysis and immunoprecipitations.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared from S. cerevisiae grown in YPD medium at 23°C until an optical density (600 nm) of ≈0.7. Glass beads were used to disrupt cells in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.05% NP-40, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol) containing protease inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 1 μg/ml benzamidine) and phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM NaF and 0.5 mM NaVO3). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad), and 1.5 mg was used for IP in a 1-ml volume. TAP-tagged proteins were precipitated overnight at 4°C with rabbit IgG-agarose in either the absence or the presence of 0.1 mg/ml RNase A to determine whether interactions were RNA dependent. Precipitates were washed three times with the IP lysis buffer, dissolved in sample buffer, and separated by 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Immunoblotting was performed using standard methods. Immunoblotting of Rpb1 was performed using the 8WG16 anti-CTD antibody (Covance), and peroxidase antiperoxidase (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to recognize the TAP tag.

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA was prepared using hot phenol extraction from S. cerevisiae grown in YPD medium at 23°C until an optical density (600 nm) of ≈0.7. Either 20 or 40 μg of total RNA was separated on a 1.2% agarose formaldehyde-MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) gel and transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N+; Amersham). To create probes for the RPB1 and RNA14 analyses, DNA fragments were PCR amplified (see oligonucleotide sequences in Table S2 in the supplemental material) from the genomic loci and used for random hexamer labeling. After hybridization and washing, membranes were exposed to X-ray film or analyzed by phosphorimager.

RESULTS

Rpb4/7 travels with core RNApII along actively transcribed genes in vivo.

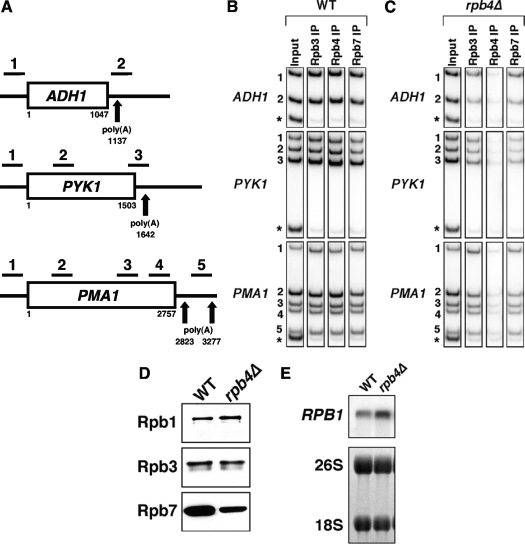

Due to the ease with which Rpb4/7 can be dissociated from the 10-subunit core of RNApII (8), as well as the finding that immunoprecipitated RNApII contains only substochiometric amounts of Rpb4/7 (18), it has been suggested that Rpb4/7 may interact with core RNApII only during certain stages of transcription, for example, only during initiation (4). To examine the involvement of Rpb4/7 during transcription in vivo, the occupancy of yeast Rpb4 and Rpb7 along three representative genes (ADH1, PYK1, and PMA1) was assayed by ChIP (Fig. 1A). In wild-type cells expressing TAP-tagged Rpb7, we find that Rpb4 and Rpb7-TAP cross-link at equal levels throughout the promoter, coding region, and 3′ end of each gene. This matches the cross-linking pattern seen for the core of the polymerase, determined by ChIP of Rpb3 as a representative subunit (Fig. 1B). As expected, an rpb4Δ strain showed no Rpb4 cross-linking. Cross-linking of Rpb7-TAP was reduced in an rpb4Δ strain compared to the level for the wild type, but the level of Rpb3 cross-linking was correspondingly reduced (Fig. 1C). Therefore, it appears that Rpb4/7 remains stoichiometrically associated with core polymerase throughout the transcription cycle. In agreement with our conclusions, human Rpb7 was recently shown to remain associated with core RNApII into the early elongation stage of transcription (5).

FIG. 1.

Relationship between the Rpb4/7 heterodimer and core of RNApII. (A) Schematic representation of the ADH1, PYK1, and PMA1 genes used in ChIP experiments. Numbers are nucleotide positions relative to the open reading frame beginning at +1. Bars above the genes represent the PCR products assayed by ChIP (see Table S2 in the supplemental material for primer sequences). Arrows indicate the major polyadenylation sites of each gene. (B) Rpb4/7 is associated with all transcribed regions. ChIP was performed using a strain expressing TAP-tagged Rpb7 (YF981). DNA coprecipitated with antibodies against Rpb3 or Rpb4 or with IgG-agarose (to precipitate TAP-tagged Rpb7) was analyzed by PCR using primers shown in panel A. The asterisk-marked PCR product is an internal background control from a nontranscribed region on chromosome VI. The input control is used to normalize for the PCR amplification efficiency of each primer pair. (C) Rpb7 associates with transcribing RNApII in the absence of Rpb4. ChIP analysis was performed as described for panel B, using an rpb4Δ strain expressing TAP-tagged Rpb7 (YSB2224). (D) Rpb7 protein levels are decreased and Rpb1 protein levels are increased in an rpb4Δ strain. Whole-cell extracts from wild-type (WT) and rpb4Δ strains expressing TAP-tagged Rpb7 were analyzed by immunoblotting with PAP to detect the TAP tag, with 8WG16 antibody (to detect Rpb1), and with anti-Rpb3. (E) RPB1 transcript levels are increased in an rpb4Δ strain. Northern blot analysis was performed for RPB1 in wild-type (YSB1140) and rpb4Δ (YSB1755) strains. Methylene blue-stained 18S and 26S rRNAs are shown as a loading control.

Immunoblotting of whole-cell extracts shows that Rpb7 levels are significantly decreased in the rpb4Δ strain (Fig. 1D). Normalized to total RNApII levels as measured by the Rpb3 subunit, loss of Rpb4 results in reduction of Rpb7 protein levels by 25 to 50%. Therefore, Rpb7 appears to be stabilized by binding to Rpb4 and this may largely account for the lack of Rpb7 in RNApII purified from rpb4Δ cells. Surprisingly, Rpb1 protein levels actually increase in the rpb4Δ strain. The increase in Rpb1 appears to be at least partly mediated by an increase in RPB1 mRNA levels (Fig. 1E) and may be a response of the cell to low levels of transcribing RNApII.

Decreased levels of RNApII are found near 3′ ends of mRNA genes in an rpb4Δ strain.

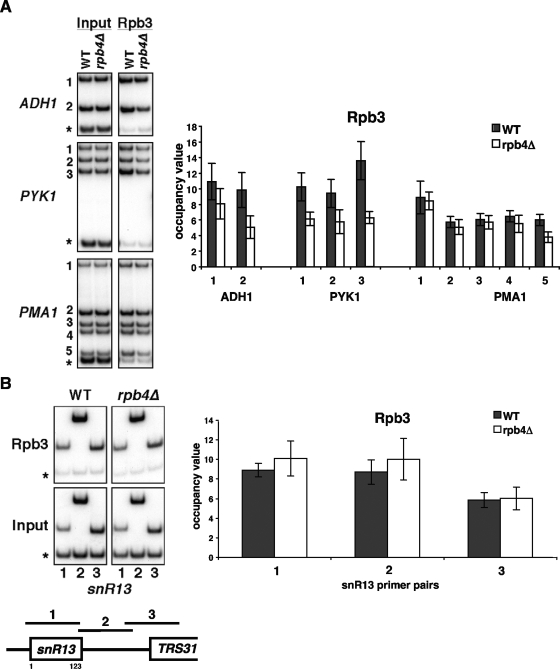

In vitro experiments show that RNApII lacking Rpb4/7 is capable of promoter-independent transcription but that the heterodimer is required for promoter-driven transcription (8). Interestingly, RNApII lacking Rpb4/7 still assembles into initiation complexes in vitro but seems unable to transition into elongation (8, 25). Since Rpb4/7 travels with core RNApII subunits along transcribed genes in vivo, it was important to test if loss of Rpb4 affected transcription elongation or termination. The ChIP assay was used to monitor the Rpb3 subunit of RNApII throughout mRNA genes in the context of both wild-type polymerase and polymerase lacking Rpb4 (Fig. 2A; also see later figures). At ADH1 and PYK1, Rpb3 cross-linking in an rpb4Δ strain is slightly reduced along the genes compared to wild-type levels, but this difference is most pronounced at the 3′ ends of the genes. At the PMA1 gene, the Rpb3 levels in the wild-type and rpb4Δ strains are roughly equal until the 3′ end of the gene, where there is a drop in Rpb3 levels in the rpb4Δ strain. It is interesting to note that the strongest decreases in Rpb3 levels coincide with the locations of the polyadenylation sites of all three genes tested. The occupancy of Rpb3 along the SNR13 gene was also analyzed. SNR13 is a snoRNA gene that is also transcribed by RNApII; like most snoRNA genes, it is much shorter than most mRNA genes. In contrast to the mRNA genes tested, Rpb3 is found at similar levels along SNR13 in the wild-type and rpb4Δ strains (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that Rpb4 might be important for RNApII processivity, particularly near 3′ ends of mRNA genes.

FIG. 2.

RNApII levels are reduced toward the 3′ ends of mRNA genes in an rpb4Δ strain. (A) ChIP was performed on the ADH1, PYK1, and PMA1 genes using anti-Rpb3 in wild-type (WT) (YSB772) and rpb4Δ strains (YSB2225). The left panel shows PCR products, and the right panel shows quantification of the results. The occupancy value is the ratio of the signal from specific primer products to the internal negative control after normalizing to the input controls. The values shown represent the averages and standard errors from three independent experiments. The asterisk-marked PCR product is an internal background control from a nontranscribed region on chromosome VI. (B) ChIP of Rpb3 shows that RNApII levels are equal along the SNR13 gene in wild-type and rpb4Δ strains. A schematic of SNR13 showing positions of PCR primers is shown below the gel. The asterisk-marked PCR product is an internal background control from a nontranscribed region on chromosome V.

Rpb4 is required for association of the 3′-end processing factor Rna14 with transcribed chromatin and RNApII.

To determine how the loss of Rpb4 affects the recruitment of various transcription factors involved in initiation, elongation, and 3′-end processing, various TAP-tagged fusion proteins were analyzed by ChIP in wild-type and rpb4Δ strains. Levels of cross-linking of initiation factors TATA-binding protein and TFIIF were equivalent at the 5′ ends of genes in wild-type and rpb4Δ strains (data not shown). Therefore, in agreement with in vitro results, Rpb4 is not necessary for preinitiation complex formation in vivo. There was also no difference in recruitment of the snoRNA termination factor Nrd1 (data not shown). Nrd1 is the homolog of S. pombe Seb1, which was shown to interact with Rpb7 in vitro (23). The lack of effect of rpb4Δ on Nrd1 may be due to the fact that Rpb7 is still associated with transcribing RNApII in this strain.

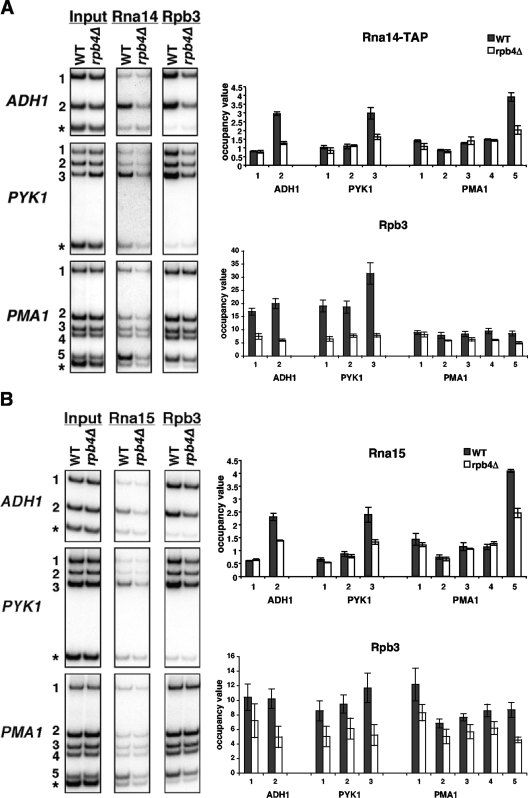

One factor that showed a marked reduction in recruitment in the rpb4Δ strain was Rna14, a core component of the 3′-end processing factor cleavage factor IA (CF IA) (14). Figure 3A shows ChIP results for Rna14-TAP in the wild-type and rpb4Δ strains at the ADH1, PYK1, and PMA1 genes. Rna14-TAP cross-linking, like other mRNA 3′-end processing factors, is strongest near the polyadenylation site of a gene in a wild-type strain (1). This signal is lost in the rpb4Δ strain at all three genes tested. To further confirm a loss of 3′-end processing factor recruitment in the rpb4Δ strain, ChIP was also performed using an antibody against the Rna15 subunit of the CF IA complex. As with Rna14, deletion of RPB4 also results in the loss of recruitment of Rna15 (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Loss of Rpb4 results in decreased occupancy of Rna14 and Rna15 at 3′ ends of mRNA genes. (A) ChIP was performed for Rna14-TAP and Rpb3 in wild-type (WT) (YSB1147) and rpb4Δ (YSB2033) strains. Quantification is shown as described in the legend for Fig. 2. The values shown represent the averages and standard errors from three independent experiments. The asterisk-marked PCR product is an internal background control from a nontranscribed region on chromosome VI. (B) ChIP was performed using antibodies against Rna15 and Rpb3 in wild-type (YSB1140 and YSB772) and rpb4Δ (YSB1755 and YSB2225) strains. Quantification is shown as described in the legend for Fig. 2.

To address the possibility that loss of Rna14 and Rna15 recruitment in the rpb4Δ strain is due either to slow growth of the strain or to a general defect in RNApII, ChIP of Rna14 and Rna15 was performed with an rpb9Δ strain. Rna14 and Rna15 recruitment is unaffected by deletion of the Rpb9 subunit of RNApII (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Normal levels of Rna14 and Rna15 at the ADH1 and PYK1 genes were also seen (data not shown) in a strain containing the slow-growing TFIIH mutant Kin28(T17D) (12, 27). This indicates that a general defect in growth or elongation is not sufficient to explain the loss of Rna14 and Rna15 recruitment in the rpb4Δ strain.

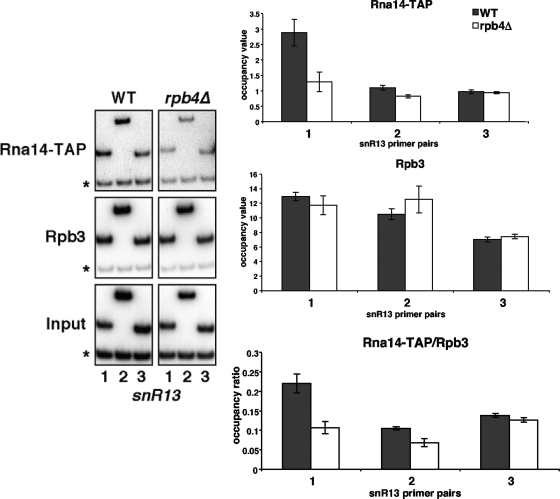

Because cross-linking for RNApII is also decreased at the 3′ ends of mRNA genes in the rpb4Δ strain, it was possible that the loss of 3′-end processing factors was simply due to the drop in total RNApII. Because Rna14 has previously been shown to cross-link to the SNR13 snoRNA gene (16) and RNApII occupancy at this gene is unaffected by RPB4 deletion (Fig. 2B), Rna14 recruitment at SNR13 was assayed. Although equivalent amounts of Rpb3 cross-linked along SNR13 in the wild-type and rpb4Δ strains, Rna14-TAP recruitment was lost in the mutant strain (Fig. 4). This finding suggests that Rpb4 is required for efficient recruitment of Rna14 to the RNApII elongation complex.

FIG. 4.

Loss of Rpb4 results in decreased occupancy of Rna14 at a snoRNA gene. ChIP for Rna14-TAP and Rpb3 was performed with wild-type (WT) (YSB1147) and rpb4Δ (YSB2033) strains. PCR analysis was performed with the SNR13 gene. The normalization (occupancy ratio) of Rna14-TAP relative to Rpb3 is shown in the bottom panel. The values shown represent the averages and standard errors from three independent experiments. The asterisk-marked PCR product is an internal background control from a nontranscribed region on chromosome V.

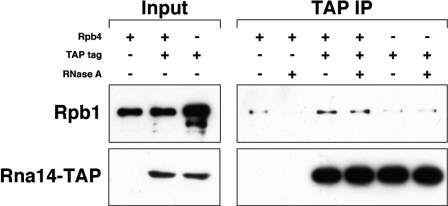

To test whether Rpb4 is required for a direct interaction between the CF IA complex and RNApII, TAP-tagged Rna14 was precipitated from whole-cell extracts of wild-type and rpb4Δ cells and assayed for the presence of Rpb1. An untagged wild-type strain was included as a negative control. As seen in Fig. 5, Rna14-TAP coprecipitates Rpb1 in a wild-type strain, but this association is lost in an rpb4Δ strain. Therefore, Rpb4 helps mediate the interaction between CF IA and RNApII. This could occur by several mechanisms. Rpb4/7 could interact directly with CF IA, Rpb4 could be required for recruiting another factor that helps recruit CF IA, or Rpb4/7 could have an effect on CTD phosphorylation at serine 2, which has been shown to promote cotranscriptional recruitment of polyadenylation factors (1).

FIG. 5.

Association of Rna14 with RNApII is dependent on Rpb4. IgG-agarose was used to precipitate TAP-tagged Rna14 from whole-cell extracts of wild-type (YSB1147) and rpb4Δ (YSB2033) strains. An untagged wild-type strain (YSB1140) was also included as a control. Immunoprecipitations were done both in the absence (−) and in the presence (+) of RNase A. Immunoblot analysis was then performed using 8WG16 antibody against Rpb1 (top) as well as the PAP antibody to detect expression of TAP-tagged Rna14 (bottom).

To examine the possibility that serine 2 phosphorylation is compromised in response to loss of Rpb4, we assayed the recruitment of Ctk1, the serine 2 kinase, in wild-type and rpb4Δ strains by ChIP. As shown in Fig. 6A, levels of Ctk1 recruitment to the PMA1 gene are equivalent in both wild-type and rpb4Δ strains. A drop is seen at the very 3′ end of the gene, which corresponds to the reduction in RNApII. Furthermore, immunoblotting of whole-cell extracts shows that levels of serine 2-phosphorylated CTD are not lost in the rpb4Δ strain (Fig. 6B). In fact, there are higher levels of phosphorylated CTD because of the higher levels of Rpb1 (Fig. 1 and data not shown). Based on these results, it appears that the loss of CF IA interaction with RNApII in an rpb4Δ strain is not due to an effect on CTD phosphorylation.

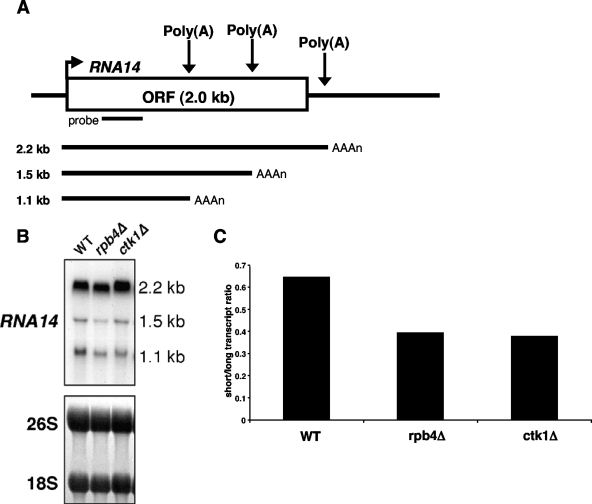

Loss of Rpb4 affects 3′-end processing in vivo.

If loss of Rpb4 results in decreased association between 3′-end processing factors and RNApII, one might expect to see 3′-end processing defects in the rpb4Δ strain. Previous experiments demonstrated that a ctk1Δ strain, which is also defective in cotranscriptional 3′-end processing factor recruitment, shows altered polyadenylation site usage at the RNA14 gene by Northern blotting (1, 29). The RNA14 gene (diagramed in Fig. 7A) produces three different transcripts (2.2, 1.5, and 1.1 kb) as a result of processing at different polyadenylation sites (30). A ctk1Δ strain produced reduced amounts of the shortest transcript (1.1 kb), while the amount of the largest transcript (2.2 kb) increased (1). This pattern is similar to that observed for strains with mutations in RNA14 or RNA15 (21), and this change may be part of a feedback mechanism to increase amounts of Rna14 in response to low levels of CF IA. The rpb4Δ strain showed a pattern very similar to that of the ctk1Δ strain, consistent with inefficient cotranscriptional polyadenylation (Fig. 7B and C). The results seen for the rpb4Δ strain are not caused by a defect in recruitment of the Ctk1 kinase, as ChIP experiments show that Ctk1 occupancy is normal in the rpb4Δ strain (Fig. 6).

FIG. 7.

Cotranscriptional 3′-end processing is compromised in an rpb4Δ strain. (A) Schematic representation of the RNA14 gene and its transcripts. ORF, open reading frame. (B) Northern blot analysis of RNA14 transcripts in wild-type (WT) (YSB1140) and rpb4Δ (YSB1755) strains. A ctk1Δ strain (YSB1142) is also shown as a control for compromised cotranscriptional 3′-end processing. Methylene blue-stained 18S and 26S rRNAs are shown as a loading control. (C) Quantification of the Northern blot experiment with results shown in panel B. Bars represent a ratio of the abundance of the two short transcripts to the abundance of the long transcript.

DISCUSSION

In vitro studies using the 10-subunit core of RNApII indicate that the Rpb4/7 heterodimer is required for promoter-dependent transcription initiation but not initiation complex assembly or promoter-independent elongation (8, 25). Here, we explore the in vivo role of Rpb4 and find that it contributes to cotranscriptional recruitment of 3′-end processing factors. In an rpb4Δ strain, fewer RNApII complexes are present at the 3′ ends of multiple mRNA genes than in a wild-type strain (Fig. 2A). This pattern of polymerase cross-linking has some similarity to that seen in cells treated with 6-azauracil, which inhibits transcription elongation by unbalancing the cellular nucleoside triphosphate concentrations (13, 33). Therefore, RNApII lacking Rpb4 may be partially defective in transcription elongation in vivo. This would be consistent with the fact that an rpb4Δ strain is sensitive to both 6-azauracil and mycophenolic acid, phenotypes often correlated with an elongation defect (7).

Coincident with lower Rpb3 occupancy at 3′ ends of mRNA genes, rpb4Δ strains do not show cotranscriptional recruitment of 3′-end processing factors Rna14 and Rna15. The decrease in polymerase may partially explain the drop in 3′-end processing factor recruitment. However, it is also possible that it is the loss of polyadenylation factor recruitment that leads to lower RNApII cross-linking at 3′ ends, particularly given findings suggesting that 3′-end signals trigger pausing of elongating polymerase (26). At each of the three mRNA genes tested, the most substantial reduction in RNApII levels in the rpb4Δ strain coincides with the polyadenylation site.

Several observations argue that Rpb4 is more directly involved in recruiting 3′-end processing factors. First, although polyadenylation factors are normally recruited to snoRNA genes (16), Rna14 recruitment to SNR13 is lost in the rpb4Δ strain (Fig. 4). This is not due to loss of RNApII, because levels of Rpb3 at SNR13 in the rpb4Δ strain are the same as levels in the wild type. The snoRNA genes are relatively short and therefore would be less susceptible to elongation defects. Second, alternative polyadenylation site usage at the RNA14 gene is altered in the rpb4Δ strain (Fig. 7). The altered usage pattern is very similar to that observed in yeast strains lacking Ctk1, a kinase necessary for cotranscriptional recruitment of polyadenylation factors (1, 21), or strains with mutations in RNA14 or RNA15 (1, 21).

A role for Rpb4 in 3′ processing factor recruitment is consistent with its location within the RNApII complex. Located near the CTD of Rpb1 as well as the transcript-exit groove (2, 3), Rpb4 is potentially in position to stabilize an interaction of 3′-end processing factors with the RNApII CTD and the polyadenylation site sequences on the emerging transcript. Such stabilization could be mediated by a direct interaction of Rpb4/7 with a polyadenylation factor, with the RNA, or with an intermediary factor. Alternatively, Rpb4/7 could be involved in modulating the CTD phosphorylation required for polyadenylation factor recruitment. In this respect, we did not observe any defects in recruitment of the CTD kinase Ctk1 (Fig. 6A) or in whole-cell levels of serine 2-phosphorylated CTD (Fig. 6B). However, others have demonstrated interactions of Rpb4/7 with the CTD phosphatase Fcp1 (10, 17).

In conclusion, our results demonstrate a new function for Rpb4 in the coupling of transcription with 3′-end processing. Combined with previous findings that Rpb4 is required for promoter-dependent transcription (8, 25) and a recent study suggesting that Rpb4 has a role in mRNA export (9), it is clear that Rpb4 plays an integral role in various stages of transcription.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Claire Moore for antibodies, TaeSoo Kim for the multiplex PCR protocol, Seong-Hoon Ahn for Kin28 mutant strains, and all members of the Buratowski lab for helpful advice and discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grants GM46498 and GM56663 to S.B.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 January 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, S. H., M. Kim, and S. Buratowski. 2004. Phosphorylation of serine 2 within the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain couples transcription and 3′ end processing. Mol. Cell 1367-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armache, K. J., H. Kettenberger, and P. Cramer. 2003. Architecture of initiation-competent 12-subunit RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1006964-6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bushnell, D. A., and R. D. Kornberg. 2003. Complete, 12-subunit RNA polymerase II at 4.1-A resolution: implications for the initiation of transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1006969-6973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choder, M. 2004. Rpb4 and Rpb7: subunits of RNA polymerase II and beyond. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29674-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cojocaru, M., C. Jeronimo, D. Forget, A. Bouchard, D. Bergeron, P. Cote, G. G. Poirier, J. Greenblatt, and B. Coulombe. 2008. Genomic location of the human RNA polymerase II general machinery: evidence for a role of TFIIF and Rpb7 at both early and late stages of transcription. Biochem. J. 409139-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer, P. 2004. RNA polymerase II structure: from core to functional complexes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14218-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desmoucelles, C., B. Pinson, C. Saint-Marc, and B. Daignan-Fornier. 2002. Screening the yeast “disruptome” for mutants affecting resistance to the immunosuppressive drug, mycophenolic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 27727036-27044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards, A. M., C. M. Kane, R. A. Young, and R. D. Kornberg. 1991. Two dissociable subunits of yeast RNA polymerase II stimulate the initiation of transcription at a promoter in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 26671-75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farago, M., T. Nahari, C. Hammel, C. N. Cole, and M. Choder. 2003. Rpb4p, a subunit of RNA polymerase II, mediates mRNA export during stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 142744-2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamenski, T., S. Heilmeier, A. Meinhart, and P. Cramer. 2004. Structure and mechanism of RNA polymerase II CTD phosphatases. Mol. Cell 15399-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keogh, M. C., and S. Buratowski. 2004. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation to map cotranscriptional mRNA processing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol. Biol. 2571-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keogh, M. C., E. J. Cho, V. Podolny, and S. Buratowski. 2002. Kin28 is found within TFIIH and a Kin28-Ccl1-Tfb3 trimer complex with differential sensitivities to T-loop phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 221288-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keogh, M. C., V. Podolny, and S. Buratowski. 2003. Bur1 kinase is required for efficient transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 237005-7018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler, M. M., J. Zhao, and C. L. Moore. 1996. Purification of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cleavage/polyadenylation factor I. Separation into two components that are required for both cleavage and polyadenylation of mRNA 3′ ends. J. Biol. Chem. 27127167-27175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, M., S. H. Ahn, N. J. Krogan, J. F. Greenblatt, and S. Buratowski. 2004. Transitions in RNA polymerase II elongation complexes at the 3′ ends of genes. EMBO J. 23354-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, M., L. Vasiljeva, O. J. Rando, A. Zhelkovsky, C. Moore, and S. Buratowski. 2006. Distinct pathways for snoRNA and mRNA termination. Mol. Cell 24723-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura, M., H. Suzuki, and A. Ishihama. 2002. Formation of a carboxy-terminal domain phosphatase (Fcp1)/TFIIF/RNA polymerase II (pol II) complex in Schizosaccharomyces pombe involves direct interaction between Fcp1 and the Rpb4 subunit of pol II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 221577-1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolodziej, P. A., N. Woychik, S. M. Liao, and R. A. Young. 1990. RNA polymerase II subunit composition, stoichiometry, and phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 101915-1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komarnitsky, P., E. J. Cho, and S. Buratowski. 2000. Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev. 142452-2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maillet, I., J. M. Buhler, A. Sentenac, and J. Labarre. 1999. Rpb4p is necessary for RNA polymerase II activity at high temperature. J. Biol. Chem. 27422586-22590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandart, E. 1998. Effects of mutations in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA14 gene on the abundance and polyadenylation of its transcripts. Mol. Gen. Genet. 25816-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKune, K., K. L. Richards, A. M. Edwards, R. A. Young, and N. A. Woychik. 1993. RPB7, one of two dissociable subunits of yeast RNA polymerase II, is essential for cell viability. Yeast 9295-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitsuzawa, H., E. Kanda, and A. Ishihama. 2003. Rpb7 subunit of RNA polymerase II interacts with an RNA-binding protein involved in processing of transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 314696-4701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyao, T., J. D. Barnett, and N. A. Woychik. 2001. Deletion of the RNA polymerase subunit RPB4 acts as a global, not stress-specific, shut-off switch for RNA polymerase II transcription at high temperatures. J. Biol. Chem. 27646408-46413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orlicky, S. M., P. T. Tran, M. H. Sayre, and A. M. Edwards. 2001. Dissociable Rpb4-Rpb7 subassembly of RNA polymerase II binds to single-strand nucleic acid and mediates a post-recruitment step in transcription initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 27610097-10102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orozco, I. J., S. J. Kim, and H. G. Martinson. 2002. The poly(A) signal, without the assistance of any downstream element, directs RNA polymerase II to pause in vivo and then to release stochastically from the template. J. Biol. Chem. 27742899-42911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez, C. R., E. J. Cho, M. C. Keogh, C. L. Moore, A. L. Greenleaf, and S. Buratowski. 2000. Kin28, the TFIIH-associated carboxy-terminal domain kinase, facilitates the recruitment of mRNA processing machinery to RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20104-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheffer, A., M. Varon, and M. Choder. 1999. Rpb7 can interact with RNA polymerase II and support transcription during some stresses independently of Rpb4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 192672-2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skaar, D. A., and A. L. Greenleaf. 2002. The RNA polymerase II CTD kinase CTDK-I affects pre-mRNA 3′ cleavage/polyadenylation through the processing component Pti1p. Mol. Cell 101429-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sparks, K. A., and C. L. Dieckmann. 1998. Regulation of poly(A) site choice of several yeast mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 264676-4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ujvari, A., and D. S. Luse. 2006. RNA emerging from the active site of RNA polymerase II interacts with the Rpb7 subunit. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 1349-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woychik, N. A., and R. A. Young. 1989. RNA polymerase II subunit RPB4 is essential for high- and low-temperature yeast cell growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 92854-2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang, L., S. Schroeder, N. Fong, and D. L. Bentley. 2005. Altered nucleosome occupancy and histone H3K4 methylation in response to ‘transcriptional stress’. EMBO J. 242379-2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.