Abstract

MDMX is an important regulator of p53 transcriptional activity and stress response. MDMX overexpression and gene amplification are implicated in p53 inactivation and tumor development. Unlike MDM2, MDMX is not inducible by p53, and little is known about its regulation at the transcriptional level. We found that MDMX levels in tumor cell lines closely correlate with promoter activity and mRNA level. Activated K-Ras and insulin-like growth factor 1 induce MDMX expression at the transcriptional level through mechanisms that involve the mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Ets-1 transcription factors. Pharmacological inhibition of MEK results in down-regulation of MDMX in tumor cell lines. MDMX overexpression was detected in ∼50% of human colon tumors and showed strong correlation with increased extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation. Therefore, MDMX expression is regulated by mitogenic signaling pathways. This mechanism may protect normal proliferating cells from p53 but also hamper p53 response during tumor development.

MDMX is a p53 binding protein and a regulator of p53 response to DNA damage and ribosomal stress (7, 14, 19). The physiological importance of MDMX was revealed by the embryonic lethality of MDMX-null mice, which can be rescued by the simultaneous knockout of p53 (13, 30, 33). MDMX overexpression has been reported in 40% of tumor cell lines (36) and 18.5% of breast, colon, and lung tumor samples (10). It is amplified in 4% of glioblastomas (37) and 5% of breast tumors (10). More recently, ∼60% of retinoblastomas have been found to have MDMX overexpression or gene amplification (22). MDMX overexpression prevents oncogenic Ras-induced premature senescence in mouse fibroblasts and cooperates with activated Ras to confer tumorigenic potential in nude mice (10). Taken together the evidence suggests that MDMX overexpression can efficiently suppress p53 and may alleviate or delay the selection for p53 mutation during tumor initiation and progression.

MDMX is structurally similar to its homolog and binding partner MDM2 (45). Unlike MDM2, which promotes p53 degradation, MDMX does not have significant intrinsic E3 ligase activity (46). MDMX forms heterodimers with MDM2 through C-terminal RING domain interactions (40, 47), which stimulates the ability of MDM2 to ubiquitinate and degrade p53 (16, 26). MDM2 can also ubiquitinate itself as well as MDMX. Under nonstress conditions, MDM2 and p53 have short half-lives whereas MDMX is relatively stable. Following DNA damage, both p53 and MDM2 are phosphorylated by several kinases (44). Most notably, ATM phosphorylates p53 on serine 15 and enhances its transcriptional activity (2). ATM also activates Chk2, which in turn phosphorylates p53 on serine 20 and inhibits binding to MDM2 (2, 6, 42, 43). ATM phosphorylation of MDM2 also inhibits its ability to degrade p53. The combination of these modifications results in the stabilization and activation of p53.

Although MDMX can regulate p53 stability by heterodimerization with MDM2, its impact on p53 level is moderate compared to MDM2. Recent studies suggest that the major mechanism of p53 regulation by MDMX is the formation of inactive p53-MDMX complexes. Therefore, elimination of MDMX is important for efficient p53 activation during stress response. DNA damage induces MDMX phosphorylation by ATM and Chk2 at several C-terminal serine residues (342, 367, and 403), generating a docking site for 14-3-3. These modifications stimulate MDMX degradation by MDM2, which facilitates p53 activation (8, 23, 31, 34). Ribosomal stress resulting from disruption of rRNA biogenesis also activates p53 in part by promoting MDMX degradation. However, ribosomal stress-induced signaling does not induce MDMX phosphorylation but promotes L11-MDM2 binding, which enhances MDMX degradation (14) and prevents p53 ubiquitination (4, 28, 52). Therefore, MDMX degradation is required for effective p53 response to DNA damage and ribosomal stress, although it occurs by different mechanisms.

MDM2 transcription is induced by p53, resulting in a classic negative feedback loop (3, 49). Furthermore, the MDM2 promoter is activated by the H-Ras oncogene through a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and c-Ets-1-dependent mechanism (38). The biological significance of MDM2 regulation at the transcriptional level is exemplified by the effect of a single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 promoter, which is associated with increased risk for cancer (5). In contrast, MDMX expression is not induced by p53, and the regulation of its promoter is still largely unknown. Recent reports suggest that the level of MDMX expression is also important in regulating p53 responses to stress signals, particularly to abnormal ribosomal biogenesis and deregulation of the Rb tumor suppressor pathway (14, 22). MDMX gene amplification accounts for only a subset of the cases of protein overexpression in cell lines and tumors, indicating that regulation of promoter activity is also responsible for MDMX overexpression.

In this report, we show that MDMX expression level is closely correlated with MDMX mRNA levels and MDMX promoter activity in different tumor cell lines. Analysis of the human MDMX proximal promoter revealed a cluster of transcription factor binding sites (c-Ets-1, Elk-1, and Aml-1) that are critical for elevated MDMX expression in tumor cell lines. However, unlike the MDM2 promoter, a survey of a large cell line panel did not reveal a sequence polymorphism in the MDMX promoter region. We also found that the K-Ras oncogene and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) induce MDMX expression through activation of mRNA transcription and that MDMX overexpression in colon tumors correlates with extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation. These results reveal that MDMX expression is under positive control by mitogenic signals and may contribute to p53 inactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and plasmids.

Tumor cell lines H1299 (lung, p53 null), A549 (lung), U2OS (bone), SJSA (bone, MDM2 amplification), MCF-7 (breast), and JEG-3 (placenta, MDM2 overexpression) were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. HCT116-p53−/− cells were kindly provided by Bert Vogelstein and maintained in McCoy 5A medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. p53-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts were provided by Gigi Lozano. 35.8 and DKO cells expressing activated K-Ras were generated by infection with retrovirus pBabe-HA-K-Ras (12V). Infected cells were selected with 1 μg/ml puromycin, and drug-resistant colonies were pooled.

Reagents.

IGF-1 (human recombinant; Sigma) was prepared as a 100-μg/ml stock solution in 0.1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Inhibitors LY294002, PD98059, SB203580, and cycloheximide were purchased from Calbiochem. At 45 min prior to IGF-1 treatment, LY294002, PD98059, or SB203580 was added to serum-deprived cells at a final concentration of 30, 37.5, or 30 μM, respectively. U0126 was purchased from Promega and used at a 30 μM concentration unless otherwise specified. Predesigned RNA interference oligonucleotides directed against c-Ets-1 or Elk-1 were purchased from Ambion, Inc.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR.

To determine levels of MDMX expression, total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit per the manufacturer's instructions. cDNAs were prepared by reverse transcription of total RNA using the SuperScript III Invitrogen kit. The primers used for Sybr green quantitative PCR of human and mouse MDMX mRNA were as follows: human MDMX, forward (FW), 5′-GCCTTGAGGAAGGATTGGTA; reverse (REV), 5′-TCGACAATCAGGGACATCAT; mouse MDMX, FW, 5′-CCATCTGACGACATGTTTCC; REV, 5′-TTACAAGCAGGACACGAAGC; 18S rRNA, FW, 5′-GATTAAGTCCCTGCCCTTTGTACA; REV, 5′-GATCCGAGGGCCTCACTAAAC.

Western blotting.

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g, and the insoluble debris was discarded. Cell lysate (10 to 50 μg of protein) was fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to Immobilon P filters (Millipore). The filter was blocked for 1 h with PBS containing 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20. The following antibodies were used: 3G9 for MDM2, 8C6 for human MDMX, 7A8 for mouse MDMX, DO-1 for p53 (Pharmingen), c-Ets-1 (N-276), Elk-1 (H-160), ERK-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-p44/p42 MAPK antibody for phosphorylated ERK (Cell Signaling Technology), and HA.11 for hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged K-Ras (Covance Research Products). The filter was developed using ECL-plus reagent (Amersham).

Construction of the MDMX promoter reporter plasmids.

To isolate the 5′ upstream region of MDMX, PCR was performed using an antisense primer in exon 1 of the MDMX gene (5′-AAGAGCCACACCTTACGGCA) and a sense primer in a 5′ genomic sequence (5′-CTATCTCGGCTCACTGCAAC) with genomic DNA isolated from MCF-7 cells as a template. The resulting 1,100-bp fragment was cloned into pDrive vector (Qiagen) and then transferred to the luciferase reporter plasmid pGL2-Basic (pGL2-FL MDMX) and was confirmed by sequencing. The mutant promoter constructs were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) in the context of the pGL2-FL MDMX according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transient-transfection and luciferase assays.

A total of 4 × 105 to 6 × 105 cells were seeded per well in 24-well plates and transfected with 50 ng of luciferase reporter plasmid, 10 ng of cytomegalovirus (CMV)-LacZ, 5 ng of green fluorescent protein, and 200 ng of single-stranded DNA using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Luciferase activity was normalized by β-galactosidase activity, and the data presented are the activation ± standard deviation from at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

ChIP assay.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was carried out using published procedures. Protein-DNA complexes from JEG-3, MCF-7, U2OS, and H1299 cells were immunoprecipitated using 1 μg of Ets-1 (N-276), Elk-1 (H-160), or YY1 (c-20) rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Coprecipitated chromatin was analyzed by PCR (30 to 32 cycles) using primers (5′-ACTCTCTCCCCGGACTAGGA and 5′-CGAGTAATGAAGCCGCAACT) to amplify the human basal MDMX promoter containing the c-Ets-1 and Elk-1 binding sites. Primers located 3 kb upstream of the basal promoter (5′-TAAACGATCCTCCCACCTTG and 5′-CCTGGAGCCTTGGAATATGA) were used as negative PCR controls.

Immunohistochemistry staining.

Tissue microarrays were deparaffinized in three changes of xylene, rehydrated, and incubated in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 20 min. Slides were incubated in 1% H2O2 for 10 min to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. The ABC staining system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used for staining. A rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against full-length His6-tagged human MDMX was affinity purified by the following procedure. Recombinant His6-MDMX protein was bound to a nitrocellulose filter and incubated with rabbit anti-MDMX serum. The filter was washed with PBS, and the bound antibody was eluted from the filter using 10 mM glycine-HCl (pH 2.7), neutralized by adding 1.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), and dialyzed in PBS. Normal goat serum (10%) was added to the final preparation as a stabilizer. The antibody was validated for its specificity using cell lines expressing different levels of endogenous and transfected MDMX. The colon tissue tumor array was stained with MDMX, phospho-ERK, and phospho-AKT (Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies. MDMX and phospho-AKT were scored based on staining intensity (1 for low intensity, 2 for intermediate staining, and 3 for intense staining). Phospho-ERK was scored as percent positive tumor cells (0 as 0%, 1 as 1 to 30%, 2 as 30 to 70%, and 3 as 70 to 100% positive).

RESULTS

MDMX level in tumor cell lines correlates with promoter activity.

Recent studies demonstrated that MDMX expression is needed for the proliferation of tumor cell lines with wild-type p53 in culture (10) and formation of tumor xenografts in nude mice (14). MDMX protein overexpression has been found in 40% of tumor cell lines (36). MDMX mRNA overexpression has also been observed in 18.5% of breast, colon, and lung tumor samples as determined by in situ hybridization (10). However, MDMX gene amplification occurs in only 5% of breast tumors (10), suggesting that in most cases activated transcription is responsible for its overexpression. Therefore, we decided to investigate the pathways that regulate MDMX transcription.

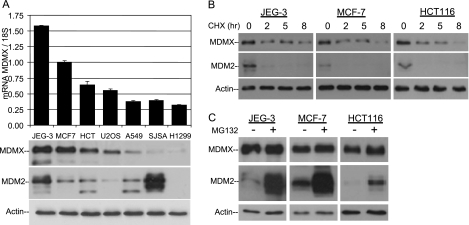

A survey of a panel of cell lines that express high (JEG-3 and MCF-7), moderate (U2OS and HCT116), and low (A549, SJSA, and H1299) levels of MDMX revealed that MDMX protein level correlated with its mRNA levels but showed no correlation with MDM2 (Fig. 1A). MDMX protein stability is much greater than that of MDM2 after treatment with cycloheximide (half-life, 4 to 8 h) and is unrelated to cellular MDM2 levels (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, blocking protein degradation with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 4 h dramatically increased the level of MDM2 but not MDMX (Fig. 1C), indicating that MDM2 but not MDMX undergoes rapid turnover in unstressed cells. Therefore, the rate of MDMX turnover is inherently low in unstressed cells and its overexpression in a subset of cell lines is not due to higher stability. These results suggest that mRNA expression is an important determinant of MDMX level in unstressed cells.

FIG. 1.

MDMX overexpression occurs at the transcriptional level. (A) Total RNAs and proteins from tumor cell lines were analyzed by quantitative PCR and Western blotting. The MDMX mRNA level was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 3). (B) JEG-3, MCF-7, and HCT116 cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX; 50 μg/ml) for 0, 2, 5, or 8 h and analyzed by Western blotting. (C) JEG-3, MCF-7, and HCT116 cells were treated with MG132 (25 μM) for 4 h and analyzed by Western blotting.

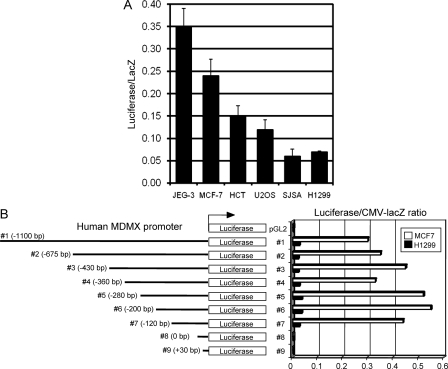

To test whether the activity of the MDMX promoter is responsible for its expression level, a 1.1-kb genomic DNA fragment upstream of the MDMX mRNA coding region was cloned by PCR and inserted into the pGL2 promoterless luciferase reporter. Transient transfection of the MDMX promoter construct into different tumor cell lines showed activity levels (normalized to cotransfected CMV and Rous sarcoma virus promoters) that generally correlated with their endogenous MDMX protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 2A), i.e., the promoter is highly active in cells overexpressing MDMX. Therefore, MDMX promoter activity is responsible for or contributes to the variations in protein levels in the tumor cell lines. It is noteworthy that MCF-7 cells in which the MDMX promoter is highly active also have abnormal MDMX gene copy number (five copies instead of two) (10), which may contribute to overexpression. Cotransfection of the MDMX promoter with several genes commonly involved in transformation (E2F1, c-myc, Stat3, Src, and AKT) did not show promoter activation (data not shown), ruling out a direct role for these factors in MDMX overexpression.

FIG. 2.

MDMX promoter analysis. (A) Cell lines were transfected with the 1.1-kb MDMX promoter-luciferase construct and CMV-LacZ. The luciferase/LacZ activity ratio is shown (n = 3). (B) MCF-7 (high endogenous MDMX expression) and H1299 (low endogenous MDMX expression) cells were transfected with MDMX promoter deletion constructs and normalized by CMV-LacZ expression (n = 3).

Identification of key transcription factor binding sites in the MDMX promoter.

To identify MDMX promoter elements necessary for promoter activity in the cell lines expressing high levels of MDMX, a series of 5′-deletion mutants were generated and transiently transfected into MCF-7 and H1299 cells (Fig. 2B). The full-length reporter fragment showed strong luciferase activity in MCF-7 cells, which have a high level of MDMX. Conversely, H1299 cells with low-level MDMX expressed weak luciferase activity. Serial deletion from bp −990 to bp −120 (0 bp being the putative transcription start site based on promoter prediction analysis and the 5′ end of the two longest cDNA sequences in GenBank, NM_002393 and BC067299) showed little effect on promoter activity in MCF-7 and H1299 cells. However, deleting the region from bp −120 to bp 0 resulted in a greater than 90% loss of promoter activity in both cell lines. These results suggest that transcription factors binding between −120 bp and 0 bp are critical for regulating both basal and cell line-specific hyperactivation of the MDMX promoter.

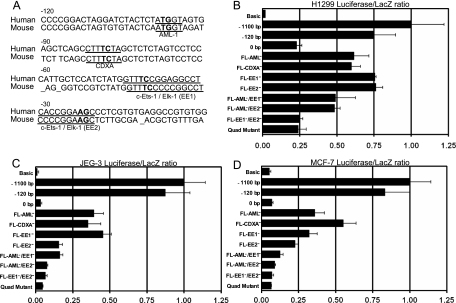

A database search for putative transcription factors which potentially bind to the region from bp −120 to 0 revealed Aml-1, Cdxa, c-Ets-1, and Elk-1 consensus sequences. These sites are largely conserved in the putative mouse MDMX promoter (Fig. 3A), suggesting that they are important for regulation of MDMX expression. c-Ets-1 and Elk-1 are downstream targets of Ras, regulated via ERK-mediated phosphorylation (15, 27). To confirm the function of these sites, point mutations at each of the potential transcription factor binding sites were introduced into the 1.1-kb promoter construct. Mutation of the Cdxa or Aml-1 sites resulted in a two- to threefold decrease in promoter activity, whereas c-Ets-1/Elk-1 individual site mutants had fourfold-reduced activity in JEG-3 and MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3C and D). Furthermore, 20-bp serial deletions of the region from bp −120 to 0 caused a stepwise decrease in promoter activity (data not shown), suggesting that multiple transcription factor binding sites are necessary for MDMX promoter activity. Compound mutations of the Aml-1 and c-Ets-1/Elk-1 sites resulted in greater than 90% reduction in promoter activity, similar to the activity of the 0-bp construct or full-length reporter with mutations in all four transcription factor binding sites (quad mutant) (Fig. 3C and D). The activity of mutant luciferase reporter constructs also changed in a pattern similar to that of H1299 cells but at a reduced magnitude (Fig. 3B), presumably because the same set of factors is functioning at a reduced level.

FIG. 3.

MDMX promoter mutation analysis. (A) Sequence of the human and mouse MDMX basal promoter (bp −120 to 0) with the positions of putative transcription factor binding sites underlined and mutated nucleotides in bold. (B to D) The full-length MDMX promoter and deletion mutations, as well as single, double, and quadruple point mutations in the full-length MDMX luciferase reporter construct, were tested for activity in H1299 (B), JEG-3 (C), and MCF-7 (D) cells (n = 3).

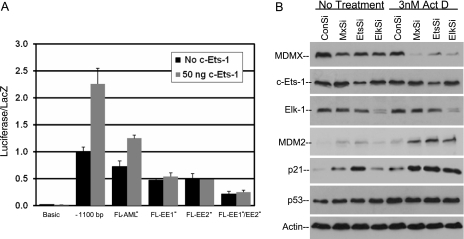

To determine whether addition of c-Ets-1 is sufficient to induce MDMX promoter activity, MDMX reporter constructs were cotransfected with a c-Ets-1 expression plasmid (Fig. 4A). c-Ets-1 induced the 1.1-kb promoter activity but was not able to activate the c-Ets-1/Elk-1 mutant promoter construct. To test the roles of endogenous c-Ets-1 and Elk-1 in regulating MDMX expression and p53 activity, U2OS cells were treated with short interfering RNA (siRNA). The results showed that transient knockdown of c-Ets-1 and Elk-1 expression reduced MDMX expression in U2OS cells (Fig. 4B). This was associated with increased expression of p53 target p21 and MDM2 without changes in p53 level. A low concentration of actinomycin D induces MDMX degradation and p53 activation by causing ribosomal stress (14). Ets-1 and Elk-1 knockdown cooperated with actinomycin D in further reducing the MDMX level and increasing p53 activity, similarly to the effect of MDMX knockdown (Fig. 4B). Therefore, c-Ets-1 and Elk-1 control MDMX transcription and contribute to the suppression of p53 activity.

FIG. 4.

MDMX basal promoter activity requires c-Ets-1 and Elk-1. (A) H1299 cells were transfected with the full-length MDMX promoter and 50 ng of c-Ets-1 plasmid to induce MDMX promoter activity. MDMX promoter mutants were also transfected with 50 ng c-Ets-1 to determine the response of each binding site mutant to c-Ets-1 expression. (B) Synthetic RNA interference oligonucleotides targeted to Elk-1, c-Ets-1, and MDMX mRNA were transfected into U2OS cells using Oligofectamine reagent. After 48 h, cells were treated with actinomycin D for 20 h and analyzed for the expression level of indicated markers by Western blotting.

Activation of MAPK pathway induces MDMX expression.

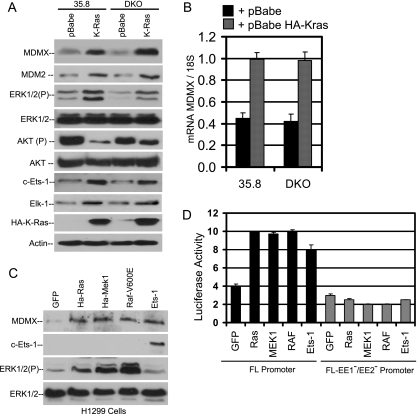

MDM2 expression is induced by oncogenic H-Ras through activation of MAPK and c-Ets-1 (38). Because c-Ets-1 also appeared to be critical for MDMX promoter activity, we tested the role of the Ras-MAPK pathway in MDMX induction. p53-null (35.8) and p53/ARF (alternate reading frame) double-null (DKO) mouse embryo fibroblasts were stably infected with retrovirus expressing HA-tagged mutant K-Ras oncogene (12V), which is more frequently involved in human cancer than H-Ras (39). K-Ras expression resulted in significant induction of MDMX in both 35.8 and DKO cells. As previously reported, levels of MDM2 were also increased in cells stably expressing mutant K-Ras. Additionally, levels of phosphorylated ERK and downstream targets c-Ets-1 and Elk-1 were elevated in K-Ras-expressing cells (Fig. 5A). Half-life comparison by cycloheximide treatment did not indicate a change in MDMX stability after K-Ras expression (data not shown). Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis showed that MDMX mRNA was increased by over twofold in K-Ras-overexpressing cells compared to vector-infected control (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the induction occurred at the transcriptional level.

FIG. 5.

MAPK activity induces MDMX expression. (A) 35.8 (p53-null) and DKO (p53/ARF-double-null) murine embryonic fibroblasts stably infected with pBabe-HA-K-Ras (12V) virus were analyzed by Western blotting for indicated markers. (B) Total RNAs from 35.8 and DKO cells expressing activated K-Ras were analyzed for MDMX mRNA level by quantitative PCR (n = 6). (C) H1299 cells were transiently transfected with HA-K-Ras, HA-MEK1, B-RafV600E, or c-Ets-1. Endogenous expression of MDMX, phospho-ERK, ERK1/2, and actin was analyzed by Western blotting. (D) H1299 cells were transfected with full-length or EE1/EE2 mutant MDMX reporter constructs and expression vectors for HA-K-Ras, HA-MEK1, B-RafV600E, or c-Ets-1. The luciferase reporter activity for each of the transfection conditions is shown (n = 3).

To further test whether downstream factors of the Ras signaling pathway have the same effect as activated K-Ras, H1299 cells with low endogenous MDMX were transiently transfected with constitutively active mutants of B-Raf (V600E) and MEK1. The results showed that expression of active B-Raf and MEK1 led to ERK phosphorylation and significant induction of MDMX protein level as expected (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, the MDMX promoter construct was stimulated by cotransfection with activated K-Ras, MEK1, and B-Raf, whereas a promoter with mutated Ets-1 binding sites was not responsive (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that activation of the Ras-Raf-MAPK pathway is sufficient to activate the MDMX promoter.

Inhibitors of the MAPK pathway down-regulate MDMX expression.

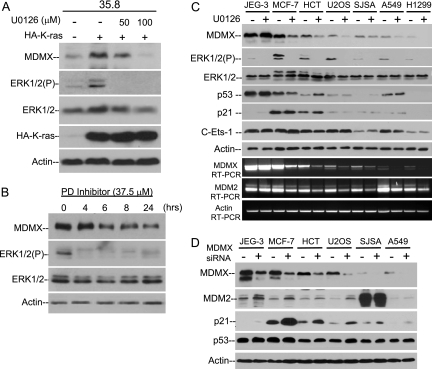

To confirm that K-Ras induction of ERK phosphorylation mediated the increase in MDMX level, 35.8-K-Ras cells were treated with the MEK inhibitor U0126 for 8 h. Inhibition of the MEK/ERK pathway by U0126 has been shown to prevent the effects of oncogenic H-Ras and K-Ras (51). U0126 treatment caused a reduction of MDMX in 35.8-K-Ras-expressing cells to levels equivalent to those in 35.8 control cells (Fig. 6A). Additionally, treatment of MCF-7 cells (high MDMX) with the MEK inhibitor PD98059 led to a time-dependent decrease in MDMX protein expression (Fig. 6B). Therefore, the results of the inhibitors were as predicted from the activation experiments.

FIG. 6.

Oncogenic K-Ras induces MDMX expression in an ERK-dependent manner. (A) 35.8 cells stably transfected with HA-K-Ras were treated with U0126 for 8 h and analyzed for expression of MDMX and phospho-ERK. (B) MCF-7 cells were treated with 37.5 μM PD98059 at indicated time points followed by Western blot analysis. (C) A panel of cell lines expressing different endogenous levels of MDMX were treated with 30 μM U0126 for 18 h and compared for expression of the indicated proteins and MDMX and MDM2 mRNA. (D) Cells were transfected with MDMX siRNA for 72 h and analyzed for expression of indicated markers by Western blotting.

To test whether there is a correlation between MAPK activation and MDMX overexpression, cell lines were compared for their p-ERK level, MDMX level, and response to UO126. The results from this small cell panel suggested a general association between high-level p-ERK and MDMX expression (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, U0126 inhibited MDMX expression in most cell lines. As expected, MDM2 levels were also decreased in the presence of U0126 (38). Therefore, strong activation signaling from the Ras/Raf/MEK/MAPK pathway may be responsible for MDMX overexpression in a majority of tumor cell lines. However, JEG-3 is an exception, with low p-ERK, high MDMX, and insensitivity to U0126 (Fig. 6C), suggesting an additional mechanism of MDMX overexpression independent of the hyperactive MAPK pathway. The activity of the MDMX promoter in JEG-3 cells still requires the Ets-1 and Elk-1 binding sites (Fig. 3C), suggesting that these transcription factors are activated by MAPK-independent mechanisms in JEG-3.

Although MAPK inhibitors suppressed MDMX expression, they did not lead to reproducible increases in p53 activity and p21 expression (Fig. 6C). U0126 treatment also failed to induce several other p53 target genes (PUMA, 14-3-3 sigma, cyclin G, and PIG-3) when tested by RT-PCR and did not activate the p53 response promoter in a reporter gene assay (data not shown). In contrast, direct knockdown of MDMX by siRNA consistently induced p21 expression in the same panel of cell lines (Fig. 6D). These results suggest that although the MAPK pathway regulates MDMX expression, targeting this pathway with MAPK inhibitors does not provide a net activation of p53. This may be due to the complex biological effects or lack of specificity of the kinase inhibitors.

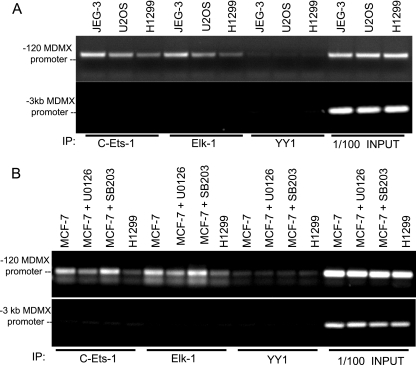

MDMX promoter activation correlates with increased Ets-1 and Elk-1 binding.

Knockdown of Ets-1 and Elk-1 by siRNA resulted in reduced MDMX expression and p53 activation, suggesting that Ets-1 and Elk-1 are important factors in mediating MDMX induction by mitogenic signals. To determine whether promoter occupancy of Ets-1 and Elk-1 correlates with MDMX promoter activity and expression level, cell lines with high and low levels of MDMX were analyzed by ChIP using Ets-1 and Elk-1 antibodies. The results confirmed that high-level MDMX expression was associated with increased promoter binding by Ets-1 and Elk-1, whereas YY1 binding was similar (Fig. 7A). The binding difference was specific for the basal promoter region and was not observed using PCR primers 3 kb upstream from the basal promoter.

FIG. 7.

c-Ets-1 and Elk-1 bind to the MDMX promoter in an ERK-dependent manner. (A) JEG-3 (high MDMX expression), U2OS, and H1299 (low MDMX expression) cells were analyzed by ChIP to detect binding of endogenous c-Ets-1 and Elk-1 to the basal MDMX promoter. YY1 was used as a negative control. PCR of a promoter element 3 kb upstream of the basal MDMX promoter was performed as a specificity control. (B) MCF-7 cells treated with 30 μM of MAPK (U0126) or p38 stress kinase inhibitor (SB203580) were compared to H1299 cells by ChIP analysis for c-Ets-1 and Elk-1 binding to the MDMX promoter.

When MCF-7 cells were treated with U0126 (MEK inhibitor) and SB203580 (p38 inhibitor), Ets-1 and Elk-1 binding to MDMX promoter was specifically reduced by U0126 but not by SB203580 (Fig. 7B). These results were also consistent with the effects of the inhibitors on MDMX expression level and promoter activity (Fig. 8). These results provide additional evidence that MAPK signaling stimulates Ets-1 and Elk-1 binding to the MDMX basal promoter, inducing MDMX expression.

FIG. 8.

IGF-1 induces ERK-dependent MCF-7 expression (A) MCF-7 cells were starved in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 0% serum for 24 h. IGF-1 (10 to 100 ng/ml) was added, and cells were analyzed 8 h later by Western blotting. (B) MCF-7 cells were transfected with MDMX promoter constructs for 24 h, serum starved for 24 h, and treated with 100 ng/ml IGF-1 for 8 h. Promoter activity was compared to that for MCF-7 cells in 10% serum (n = 3). (C) MCF-7 cells were serum starved for 24 h and treated with IGF-1 and inhibitors of PI3K (30 μM LY294002), MAPK (37.5 μM PD98059), or p38 kinase (30 μM SB203580) for 8 h. Cell lysate was analyzed by Western blotting. (D) Total RNAs from serum-starved MCF-7 cells treated with IGF-1, 30 μM LY294002, 37.5 μM PD98059, and 30 μM SB203580 were analyzed for MDMX mRNA levels by quantitative PCR (n = 3).

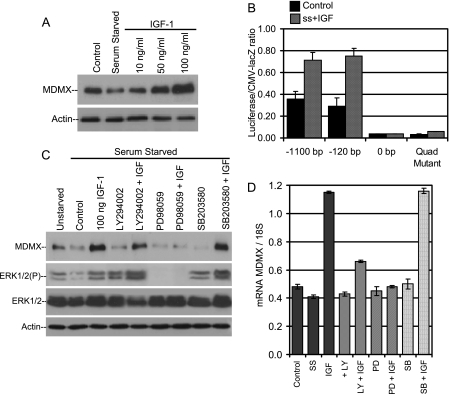

IGF-1 increases expression of MDMX in a MAPK-dependent manner.

The involvement of the Ras-MAPK pathway in stimulating MDMX expression suggests that extracellular growth factors may also influence MDMX expression. Mitogenic stimulation by fibroblast growth factor, IGF-1, or activated platelet-derived growth factor receptor has been shown to inhibit the p53 pathway by inducing MDM2 transcription (12, 41). Additionally, IGF-1-induced cell division correlates with nuclear exclusion of p53 and enhanced p53 degradation (20). MCF-7 cells have been shown to have up-regulated IGF receptor (IGFR-1) mRNA and protein (9). To address the role of MDMX in mitogenic signaling to p53, serum-starved MCF-7 cells were treated with IGF-1. This led to a marked increase of MDMX expression after 8 h (Fig. 8A). Additionally, IGF-1 stimulation of MCF-7 also led to an increase in activity of the transfected MDMX promoter (Fig. 8B). These results indicate that MDMX expression can be regulated by extracellular growth factors.

The biological effects of IGF-1 are mediated by the activation of the IGF-1 receptor, a transmembrane tyrosine kinase linked to the AKT and Ras-Raf-MAPK cascades (11). To evaluate which signaling pathway is involved in IGF-1-mediated MDMX induction, serum-starved MCF-7 cells were stimulated with IGF-1 in the presence of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor (LY294002), MEK inhibitor (PD98059), or p38 stress kinase inhibitor (SB203580). IGF-1 induction of MDMX was completely blocked by the MEK inhibitor PD98059 but not by the PI3K or p38 inhibitors (Fig. 8C). The level of phosphorylated ERK, which decreased following serum starvation, was increased upon the addition of IGF-1, confirming that IGF-1 was activating the MAPK pathway. As expected, PD98059 completely abrogated ERK phosphorylation whereas LY294002 and SB203580 had no effect (Fig. 8C). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that IGF-1 induced MDMX mRNA expression by threefold over unstimulated MCF-7 cells (Fig. 8D). Additionally, the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 completely abrogated the induction of MDMX mRNA, while the p38 inhibitor had no effect. The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 was able to partially suppress MDMX mRNA expression. This is likely due to the cooperation between the PI3K and Ras activation pathways, which may act synergistically to increase ERK phosphorylation.

MDMX overexpression correlates with ERK phosphorylation in colorectal tumors.

MDMX mRNA overexpression has been observed in 18.5% of breast, colon, and lung tumor samples as determined by in situ hybridization (10). MDMX protein expression was also observed in ∼80% of adult pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemias by immunohistochemical staining (17), suggesting that its expression is associated with common changes in signaling pathways in tumor cells.

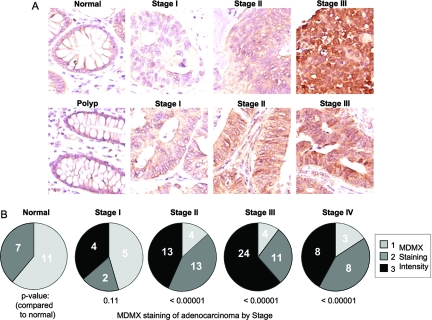

To verify the observation of MDMX overexpression in human tumors and to test the association with hyperactive MAPK signaling, we performed immunohistochemical staining of a panel of colon tumors and normal colon mucosa controls. The results showed that normal mucosa expressed low levels of MDMX, whereas ∼49% (49/99) of colon tumors expressed high-level MDMX as a diffused stain in both the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 9A). MDMX overexpression was more frequently observed in high-grade tumors (Fig. 9B). The tumor array was also analyzed for p53 overexpression, which serves as an indicator of p53 mutation. The results revealed that p53 and MDMX overexpression were independently associated with high-grade tumors (data not shown). These results suggest that MDMX expression is elevated in aggressive tumors and occurs independently of p53 mutation status.

FIG. 9.

MDMX expression increases with tumor stage. (A) Representative MDMX immunohistochemical staining of normal colon mucosa and stage I to III tumors from a colon cancer tissue microarray (brown). An increased staining intensity as a function of tumor stage was observed. (B) Each tumor in the array was manually scored according to MDMX staining intensity from 1 to 3 and displayed according to the stage of colon cancer progression. The correlation between intensity of MDMX staining and the stage of colon cancer was calculated using Spearman's correlation analysis (n = 117; r2 = 0.36; P < 0.0001). MDMX staining intensity in each stage was compared to that for normal colon mucosa, and the P value is indicated.

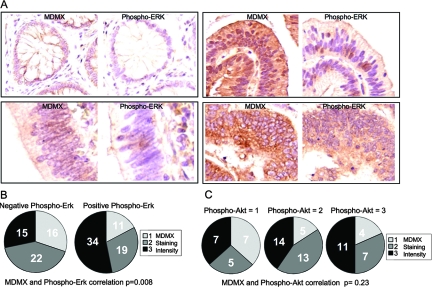

Staining of the same tumor array using a phospho-ERK monoclonal antibody revealed a mosaic pattern of staining (20 to 40% cells positive) in a subset of tumors (Fig. 10A). Tumors staining positive for phospho-ERK are twofold more likely to also have MDMX overexpression (Fig. 10B). Unlike phospho-ERK, the intensity of phospho-AKT staining showed no correlation with MDMX staining (Fig. 10C). These results are consistent with cell culture analysis and suggest that hyperactive MAPK signaling may stimulate MDMX overexpression and compromise the p53 pathway.

FIG. 10.

MDMX expression correlates with phospho-ERK level in colon cancer. (A) Representative pictures of colon tumors stained for MDMX (left) or phospho-ERK (right). Each pair of pictures is from consecutive sections of the same tumor at the same position. (B) Intensity of MDMX staining in the phospho-ERK-positive and -negative colon carcinomas. The correlation between intensity of MDMX staining and phospho-ERK was calculated using Spearman's correlation analysis (n = 117; r2 = 0.24; P = 0.008). (C) A comparison of MDMX and phospho-AKT staining intensities in the colon microarray. There is no significant correlation between intensity of MDMX staining and phospho-AKT as calculated using Spearman's correlation analysis (n = 73; r2 = 0.14; P = 0.22).

Absence of sequence polymorphism in the MDMX basal promoter.

The MDM2 P2 promoter (p53 responsive) contains a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP309) which is heterozygous in 40% and homozygous in 12% of the sample population, which results in increased binding by the Sp1 transcription factor and increased MDM2 expression (5). Importantly, the SNP309 allele is associated with a higher risk for cancer, presumably due to attenuated p53 function. Therefore, we asked whether promoter sequence polymorphism contributes to different levels of MDMX expression in tumor cell lines. A 0.7-kb region of the MDMX promoter (bp 0 to −700) was amplified from the genomic DNA of 30 human cell lines (27 tumor cell lines and three skin fibroblasts) and analyzed by DNA sequencing. The analysis identified only one cell line (K562) with a single nucleotide polymorphism, which is located outside of the region from bp −120 to 0 (data not shown). Sequencing results further upstream of the basal promoter were uninformative due to artifacts caused by multiple poly(T) tracks. Therefore, the MDMX basal promoter does not contain significant sequence polymorphism.

DISCUSSION

A significant difference between MDM2 and MDMX regulation is that MDMX transcription is not activated by p53. However, results described above identified important similarities in the induction of both MDM2 and MDMX by the Ras-MAPK and growth factor pathways (18, 24, 38). This finding provides an explanation for the frequent overexpression of MDMX in tumors, often in the absence of gene amplification. Induction of MDM2 and MDMX expression by the mitogenic pathways may serve to prevent unwanted p53 activation during normal cell proliferation in development and homeostasis. However, when inappropriately activated, this pathway also has oncogenic potential by blocking the tumor suppression functions of p53 during abnormal cell proliferation. Recent studies show that increased circulating IGF-1 levels put individuals at a higher risk for developing numerous types of cancers (21). Induction of MDM2 and MDMX may play a role in this process.

Following an initial oncogenic insult such as Ras mutation, MDMX and MDM2 induction by the MAPK pathway may suppress p53 activity and facilitate initial tumor progression. MDMX induction may also attenuate ARF activation of p53 (25). However, the lack of association between MDMX overexpression and p53 mutation in colon tumors suggests that MDMX is not sufficient to bypass the selection for p53 mutations. A previous study also showed that MDM2 gene amplification does not obviate the need for silencing ARF expression (29). It is possible that in advanced-stage tumors, strong ARF induction by multiple activated oncogenes is dominant over the MAPK-MDM2/MDMX pathway, creating selection pressure for p53 mutation or ARF silencing. Consistent with this notion, ARF overexpression stimulates MDMX ubiquitination and degradation by MDM2 (unpublished results) (32). Therefore, loss of ARF by epigenetic silencing or deletion is a key event that unleashes the oncogenic potential of the MAPK-MDM2/MDMX pathway, giving tumor cells with hyperactive MAPK an advantage in terms of resistance to p53.

MDM2 promoter polymorphism is prevalent among the human population, probably due to a certain level of evolutionary advantage that it confers on the carriers at the expense of increased cancer risk. It is unclear whether MDMX expression level is affected by promoter polymorphism. Our sequence analysis of 30 human cell lines did not reveal significant variation in a 1.4-kb region including the proximal promoter and transcription factor binding sites necessary for basal and Ras-induced expression. Therefore, it is possible that sequence variations in this region that lead to increased or decreased MDMX expression do not confer a selection advantage and failed to accumulate in the population. However, these results do not rule out the presence of sequence polymorphism in other parts of the MDMX gene that may affect its transcription, splicing, and ability to regulate p53.

Recent studies have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of MDMX as a drug target in cancer. Knockout experiments suggest that elimination of MDMX leads to significant activation of p53. Reduction of MDMX gene dosage delays myc-induced lymphoma in mice (48). Furthermore, short hairpin RNA knockdown of MDMX expression activates p53 in cell culture and abrogates tumor xenograft formation by HCT116 cells (14). Therefore, down-regulation of MDMX expression is a useful therapeutic strategy. However, our results in this report suggest that although the MAPK pathway regulates MDMX expression, targeting this pathway by kinase inhibitors may not provide a net activation of p53. This may be due to the complexity of the MAPK pathway, involvement of Ets-1 in regulating p21 expression (50), and toxicity of the kinase inhibitors. It has been shown that MEK activity is required for expression of p53 at the transcriptional level and also for p53 activation by genotoxic agents (1, 35). Therefore, more specific approaches that directly target MDMX expression or activity are necessary for effective p53 activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Moffitt Molecular Biology Core for DNA sequencing and quantitative PCR, Tissue Core for providing tumor arrays, Patrick Copock for cloning the MDMX promoter, and Zhixiong Xiao for helpful advice on IGF-1.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to J. Chen. D. M. Gilkes is a recipient of a Presidential Graduate Fellowship from the University of South Florida.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 January 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agarwal, M. L., C. V. Ramana, M. Hamilton, W. R. Taylor, S. E. DePrimo, L. J. Bean, A. Agarwal, M. K. Agarwal, A. Wolfman, and G. R. Stark. 2001. Regulation of p53 expression by the RAS-MAP kinase pathway. Oncogene 202527-2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banin, S., L. Moyal, S. Shieh, Y. Taya, C. W. Anderson, L. Chessa, N. I. Smorodinsky, C. Prives, Y. Reiss, Y. Shiloh, and Y. Ziv. 1998. Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 by ATM in response to DNA damage. Science 2811674-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barak, Y., T. Juven, R. Haffner, and M. Oren. 1993. mdm2 expression is induced by wild type p53 activity. EMBO J. 12461-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat, K. P., K. Itahana, A. Jin, and Y. Zhang. 2004. Essential role of ribosomal protein L11 in mediating growth inhibition-induced p53 activation. EMBO J. 232402-2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond, G. L., W. Hu, E. E. Bond, H. Robins, S. G. Lutzker, N. C. Arva, J. Bargonetti, F. Bartel, H. Taubert, P. Wuerl, K. Onel, L. Yip, S. J. Hwang, L. C. Strong, G. Lozano, and A. J. Levine. 2004. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 promoter attenuates the p53 tumor suppressor pathway and accelerates tumor formation in humans. Cell 119591-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chehab, N. H., A. Malikzay, M. Appel, and T. D. Halazonetis. 2000. Chk2/hCds1 functions as a DNA damage checkpoint in G(1) by stabilizing p53. Genes Dev. 14278-288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, L., D. M. Gilkes, Y. Pan, W. S. Lane, and J. Chen. 2005. ATM and Chk2-dependent phosphorylation of MDMX contribute to p53 activation after DNA damage. EMBO J. 243411-3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, L., C. Li, Y. Pan, and J. Chen. 2005. Regulation of p53-MDMX interaction by casein kinase 1 alpha. Mol. Cell. Biol. 256509-6520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke, R. B., A. Howell, and E. Anderson. 1997. Type I insulin-like growth factor receptor gene expression in normal human breast tissue treated with oestrogen and progesterone. Br. J. Cancer 75251-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danovi, D., E. Meulmeester, D. Pasini, D. Migliorini, M. Capra, R. Frenk, P. de Graaf, S. Francoz, P. Gasparini, A. Gobbi, K. Helin, P. G. Pelicci, A. G. Jochemsen, and J. C. Marine. 2004. Amplification of Mdmx (or Mdm4) directly contributes to tumor formation by inhibiting p53 tumor suppressor activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 245835-5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datta, S. R., A. Brunet, and M. E. Greenberg. 1999. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 132905-2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fambrough, D., K. McClure, A. Kazlauskas, and E. S. Lander. 1999. Diverse signaling pathways activated by growth factor receptors induce broadly overlapping, rather than independent, sets of genes. Cell 97727-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finch, R. A., D. B. Donoviel, D. Potter, M. Shi, A. Fan, D. D. Freed, C. Y. Wang, B. P. Zambrowicz, R. Ramirez-Solis, A. T. Sands, and N. Zhang. 2002. mdmx is a negative regulator of p53 activity in vivo. Cancer Res. 623221-3225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilkes, D. M., L. Chen, and J. Chen. 2006. MDMX regulation of p53 response to ribosomal stress. EMBO J. 255614-5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gille, H., M. Kortenjann, O. Thomae, C. Moomaw, C. Slaughter, M. H. Cobb, and P. E. Shaw. 1995. ERK phosphorylation potentiates Elk-1-mediated ternary complex formation and transactivation. EMBO J. 14951-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu, J., H. Kawai, L. Nie, H. Kitao, D. Wiederschain, A. G. Jochemsen, J. Parant, G. Lozano, and Z. M. Yuan. 2002. Mutual dependence of MDM2 and MDMX in their functional inactivation of p53. J. Biol. Chem. 27719251-19254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han, X., G. Garcia-Manero, T. J. McDonnell, G. Lozano, L. J. Medeiros, L. Xiao, G. Rosner, M. Nguyen, M. Fernandez, Y. A. Valentin-Vega, J. Barboza, D. M. Jones, G. Z. Rassidakis, H. M. Kantarjian, and C. E. Bueso-Ramos. 2007. HDM4 (HDMX) is widely expressed in adult pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia and is a potential therapeutic target. Mod. Pathol. 2054-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heron-Milhavet, L., and D. LeRoith. 2002. Insulin-like growth factor I induces MDM2-dependent degradation of p53 via the p38 MAPK pathway in response to DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 27715600-15606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu, B., D. M. Gilkes, B. Farooqi, S. M. Sebti, and J. Chen. 2006. MDMX overexpression prevents p53 activation by the MDM2 inhibitor Nutlin. J. Biol. Chem. 28133030-33035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson, M. W., L. E. Patt, G. A. LaRusch, D. B. Donner, G. R. Stark, and L. D. Mayo. 2006. Hdm2 nuclear export, regulated by insulin-like growth factor-I/MAPK/p90Rsk signaling, mediates the transformation of human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 28116814-16820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson, O., A. Girnita, and L. Girnita. 2005. Role of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor signalling in cancer. Br. J. Cancer 922097-2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laurie, N. A., S. L. Donovan, C. S. Shih, J. Zhang, N. Mills, C. Fuller, A. Teunisse, S. Lam, Y. Ramos, A. Mohan, D. Johnson, M. Wilson, C. Rodriguez-Galindo, M. Quarto, S. Francoz, S. M. Mendrysa, R. K. Guy, J. C. Marine, A. G. Jochemsen, and M. A. Dyer. 2006. Inactivation of the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma. Nature 44461-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeBron, C., L. Chen, D. M. Gilkes, and J. Chen. 2006. Regulation of MDMX nuclear import and degradation by Chk2 and 14-3-3. EMBO J. 251196-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leri, A., Y. Liu, P. P. Claudio, J. Kajstura, X. Wang, S. Wang, P. Kang, A. Malhotra, and P. Anversa. 1999. Insulin-like growth factor-1 induces Mdm2 and down-regulates p53, attenuating the myocyte renin-angiotensin system and stretch-mediated apoptosis. Am. J. Pathol. 154567-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, C., L. Chen, and J. Chen. 2002. DNA damage induces MDMX nuclear translocation by p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 227562-7571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linares, L. K., A. Hengstermann, A. Ciechanover, S. Muller, and M. Scheffner. 2003. HdmX stimulates Hdm2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10012009-12014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, S., Y. Liang, H. Huang, L. Wang, Y. Li, J. Li, X. Li, and H. Wang. 2005. ERK-dependent signaling pathway and transcriptional factor Ets-1 regulate matrix metalloproteinase-9 production in transforming growth factor-beta 1 stimulated glomerular podocytes. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 16207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohrum, M. A., R. L. Ludwig, M. H. Kubbutat, M. Hanlon, and K. H. Vousden. 2003. Regulation of HDM2 activity by the ribosomal protein L11. Cancer Cell 3577-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu, W., J. Lin, and J. Chen. 2002. Expression of p14ARF overcomes tumor resistance to p53. Cancer Res. 621305-1310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Migliorini, D., E. Lazzerini Denchi, D. Danovi, A. Jochemsen, M. Capillo, A. Gobbi, K. Helin, P. G. Pelicci, and J. C. Marine. 2002. Mdm4 (Mdmx) regulates p53-induced growth arrest and neuronal cell death during early embryonic mouse development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 225527-5538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okamoto, K., K. Kashima, Y. Pereg, M. Ishida, S. Yamazaki, A. Nota, A. Teunisse, D. Migliorini, I. Kitabayashi, J. C. Marine, C. Prives, Y. Shiloh, A. G. Jochemsen, and Y. Taya. 2005. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of MdmX at serine 367 activates p53 by targeting MdmX for Mdm2-dependent degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 259608-9620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan, Y., and J. Chen. 2003. MDM2 promotes ubiquitination and degradation of MDMX. Mol. Cell. Biol. 235113-5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parant, J. M., V. Reinke, B. Mims, and G. Lozano. 2001. Organization, expression, and localization of the murine mdmx gene and pseudogene. Gene 270277-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pereg, Y., S. Lam, A. Teunisse, S. Biton, E. Meulmeester, L. Mittelman, G. Buscemi, K. Okamoto, Y. Taya, Y. Shiloh, and A. G. Jochemsen. 2006. Differential roles of ATM- and Chk2-mediated phosphorylations of Hdmx in response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 266819-6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Persons, D. L., E. M. Yazlovitskaya, and J. C. Pelling. 2000. Effect of extracellular signal-regulated kinase on p53 accumulation in response to cisplatin. J. Biol. Chem. 27535778-35785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramos, Y. F., R. Stad, J. Attema, L. T. Peltenburg, A. J. van der Eb, and A. G. Jochemsen. 2001. Aberrant expression of HDMX proteins in tumor cells correlates with wild-type p53. Cancer Res. 611839-1842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riemenschneider, M. J., R. Buschges, M. Wolter, J. Reifenberger, J. Bostrom, J. A. Kraus, U. Schlegel, and G. Reifenberger. 1999. Amplification and overexpression of the MDM4 (MDMX) gene from 1q32 in a subset of malignant gliomas without TP53 mutation or MDM2 amplification. Cancer Res. 596091-6096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ries, S., C. Biederer, D. Woods, O. Shifman, S. Shirasawa, T. Sasazuki, M. McMahon, M. Oren, and F. McCormick. 2000. Opposing effects of Ras on p53: transcriptional activation of mdm2 and induction of p19ARF. Cell 103321-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sebolt-Leopold, J. S., and R. Herrera. 2004. Targeting the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to treat cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4937-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharp, D. A., S. A. Kratowicz, M. J. Sank, and D. L. George. 1999. Stabilization of the MDM2 oncoprotein by interaction with the structurally related MDMX protein. J. Biol. Chem. 27438189-38196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaulian, E., D. Resnitzky, O. Shifman, G. Blandino, A. Amsterdam, A. Yayon, and M. Oren. 1997. Induction of Mdm2 and enhancement of cell survival by bFGF. Oncogene 152717-2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shieh, S. Y., J. Ahn, K. Tamai, Y. Taya, and C. Prives. 2000. The human homologs of checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Cds1 (Chk2) phosphorylate p53 at multiple DNA damage-inducible sites. Genes Dev. 14289-300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shieh, S. Y., M. Ikeda, Y. Taya, and C. Prives. 1997. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53 alleviates inhibition by MDM2. Cell 91325-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shiloh, Y. 2003. ATM: ready, set, go. Cell Cycle 2116-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shvarts, A., W. T. Steegenga, N. Riteco, T. van Laar, P. Dekker, M. Bazuine, R. C. van Ham, W. van der Houven van Oordt, G. Hateboer, A. J. van der Eb, and A. G. Jochemsen. 1996. MDMX: a novel p53-binding protein with some functional properties of MDM2. EMBO J. 155349-5357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stad, R., N. A. Little, D. P. Xirodimas, R. Frenk, A. J. van der Eb, D. P. Lane, M. K. Saville, and A. G. Jochemsen. 2001. Mdmx stabilizes p53 and Mdm2 via two distinct mechanisms. EMBO Rep. 21029-1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanimura, S., S. Ohtsuka, K. Mitsui, K. Shirouzu, A. Yoshimura, and M. Ohtsubo. 1999. MDM2 interacts with MDMX through their RING finger domains. FEBS Lett. 4475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terzian, T., Y. Wang, C. S. Van Pelt, N. F. Box, E. L. Travis, and G. Lozano. 2007. Haploinsufficiency of Mdm2 and Mdm4 in tumorigenesis and development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 275479-5485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu, X., J. H. Bayle, D. Olson, and A. J. Levine. 1993. The p53-mdm-2 autoregulatory feedback loop. Genes Dev. 71126-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang, C., M. M. Kavurma, A. Lai, and L. M. Khachigian. 2003. Ets-1 protects vascular smooth muscle cells from undergoing apoptosis by activating p21WAF1/Cip1: ETS-1 regulates basal and inducible p21WAF1/Cip1 transcription via distinct cis-acting elements in the p21WAF/Cip1 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 27827903-27909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, J., and H. F. Lodish. 2004. Constitutive activation of the MEK/ERK pathway mediates all effects of oncogenic H-ras expression in primary erythroid progenitors. Blood 1041679-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang, Y., G. W. Wolf, K. Bhat, A. Jin, T. Allio, W. A. Burkhart, and Y. Xiong. 2003. Ribosomal protein L11 negatively regulates oncoprotein MDM2 and mediates a p53-dependent ribosomal-stress checkpoint pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 238902-8912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]