Abstract

Chromatin remodeling is central to the regulation of transcription elongation. We demonstrate that the conserved Saccharomyces cerevisiae histone chaperone Nap1 associates with chromatin. We show that Nap1 regulates transcription of PHO5, and the increase in transcript level and the higher phosphatase activity plateau observed for Δnap1 cells suggest that the net function of Nap1 is to facilitate nucleosome reassembly during transcription elongation. To further our understanding of histone chaperones in transcription elongation, we identified factors that regulate the function of Nap1 in this process. One factor investigated is an essential mRNA export and TREX complex component, Yra1. Nap1 interacts directly with Yra1 and genetically with other TREX complex components and the mRNA export factor Mex67. Additionally, we show that the recruitment of Nap1 to the coding region of actively transcribed genes is Yra1 dependent and that its recruitment to promoters is TREX complex independent. These observations suggest that Nap1 functions provide a new connection between transcription elongation, chromatin assembly, and messenger RNP complex biogenesis.

Chromatin consists of DNA wrapped around the histone octamer to form regularly spaced nucleosomes. Chromatin assembly and disassembly play regulatory roles in many cellular processes and are central to transcription, replication, and DNA repair. The transcription of mRNA is a coordinated dynamic process, balancing promoter activation, chromatin remodeling, initiation, elongation, processing, termination, and export (4, 27, 45). Transcription is generally thought to correlate with a reduction in histone density on the DNA template allowing for the passage of RNA polymerase II (RNAP II), and it has been shown that histones can be selectively removed and replaced by chromatin remodeling factors and histone chaperones (27, 45). Reassembly of the octamers prevents initiation of transcription from cryptic sites within the open reading frame (ORF) (27). Critically for these processes, histone chaperones must target histones to the correct chromatin domains or to other chromatin assembly complexes. Histone chaperones play important roles in chromatin metabolism, although in most cases, their exact functions in transcription, nuclear import, replication, or DNA repair have yet to be elucidated.

The yeast nucleosome assembly protein Nap1 is an evolutionarily conserved histone chaperone. Nap1 is a particularly enigmatic member of this family, initially characterized by its ability to form nucleosomes using core histones on a plasmid template (18). Since then, numerous studies have revealed the role of Nap1 in both histone import and bud development, the structure of the Nap1 dimer, the in vitro activity of Nap1 in chromatin assembly, and interactions with ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes (40, 57). Genetic interactions identified so far have indicated an important role for Nap1 during bud development and the G2/M transition (40, 57). We set out to understand how chromatin assembly and disassembly regulates transcription and how this important histone chaperone functions in the nucleus. Previous work in our lab demonstrated that Nap1 facilitates the preferential association between the histones H2A and H2B with the nuclear import karyopherin Kap114 (36). Nap1 is also a nuclear shuttling protein, a function important for transcription of Ty elements (36). Additionally, Kap114 regulates the Nap1 deposition of histones in a Ran-GTP-sensitive fashion (35). This suggests coordination between karyopherin-mediated nuclear transport and the histone chaperone activity of Nap1. During transcription elongation, complexes like RSC and FACT and the histone chaperone Asf1 coordinate nucleosome rearrangement (7, 43, 47). Both RSC and FACT complexes appear to interact with Nap1 (9, 25). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that the RSC complex and Nap1 facilitate the disassembly of nucleosomes in vitro (30). However, in vivo evidence of Nap1 recruitment to chromatin has remained elusive.

Many of the factors involved in pre-mRNA elongation, splicing, and mRNA export are cotranscriptionally recruited to the pre-mRNA (4). From the first steps of initiation, the pre-mRNA exists as a messenger ribonucleoprotein complex (mRNP), bound by numerous proteins. Loading of elongation factors onto the pre-mRNP is important for RNAP II processivity. Several proteomic screens involving large-scale affinity purification schemes revealed numerous interacting partners for Nap1 (14, 25). As expected, Kap114, H2A, H2B, and several factors found at the yeast bud neck were identified. A common factor found in these screens is Yra1, a conserved essential component of the TREX mRNA transcription and export complex (14, 20, 25, 51). The TREX complex is composed of Yra1, Sub2, and the THO subcomplex (Mft1, Hpr1, Thp2, and Tho2) and links pre-mRNA formation during transcription elongation with mRNA export via interactions with the export factor Mex67 (15, 50, 51, 55, 56). The TREX complex associates with RNAP II within ORFs and is enriched at the 3′ end of the ORF (1, 22, 51, 56). While Nap1 may be targeted to a variety of chromatin regions through its interactions with histones, its interaction with Yra1 points to a new regulatory mechanism.

In this study, we provide unique physical and genetic evidence that support a role for Nap1-mediated nucleosome rearrangement during transcription elongation. We demonstrate that Nap1 associates with chromatin; moreover, its localization to ORFs of actively transcribed genes is Yra1 dependent. The functional interaction between Nap1 and the TREX complex represents a new connection between chromatin remodeling and mRNP biogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and yeast strains.

The Yra1 shuffle plasmid pYra1 was made by insertion of YRA1 (with intron) into pRS416ADH. The pYra1-FLAG plasmids were made by insertion of YRA1 (with intron) into pRS415ADH and YRA1 into pGEX-4T1 (Amersham) with a 3′ oligonucleotide encoding one FLAG epitope 5′ of the stop codon. The FLAG-green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression plasmid was made by insertion of the GFP ORF into pFLAG-2 (Sigma). A glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Yra1 expression plasmid was made by insertion of YRA1 into pGEX-4T1. pYra1-GFP2 was made using pGFP2-C-FUS (36). Hemagglutinin (HA)-Nap1 was expressed from pRS313 containing the NAP1 ORF with one HA epitope 3′ of the start codon flanked by the NAP1 promoter and terminator sequences. NAP1 overexpression was achieved using pRS425GPD. The yra1-1 and mex67-5 plasmids were previously described (48, 50).

Yeast strains used in this study were derived from DF5 (11) or BY4741 (Open Biosystems). The Yra1 shuffle strain was generated by integration of ClonNAT into the YRA1 ORF of cells transformed with pYra1. Cells expressing Yra1-FLAG or yra1-1 were made by shuffling the respective plasmid on selection media and 5-fluoroorotic acid. The MEX67 ORF was disrupted in cells exogenously expressing mex67-5 with KanMX. The NAP1 ORF was disrupted in Yra1-FLAG-, yra1-1-, and mex67-5-expressing cells with URA3, KanMX, and ClonNAT, respectively. Δnap1 double mutants were made by mating BY4741 deletion strains (Δmft1 and Δthp2) with the Δnap1::cloNAT strain (derived from strain Y2454 from C. Boone; MATα ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 his3Δ1 lys2Δ0 MFA1pr-HIS3 can1Δ0) and performing tetrad dissections. The NAP1-TAP strain was obtained commercially (Open Biosystems). NAP1-3HA was integrated into the NAP1 ORF of the yra1-1 strain using pFA6a-3HA-KanMX6 (29). The FLAG-H2B strain YZS276 was previously described (52). NAP1 was deleted in the FLAG-H2B strain by using KanMX.

Immunoprecipitations.

Nap1-TAP was isolated from a NAP1-TAP strain grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.5 in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose medium (YPD). Cells were washed, spheroplasted, and then lysed by sonication in 5 ml of 8% polyvinylpyrrolidone-0.025% Triton X-100-5 mM dithiothreitol-protease inhibitors. Whole-cell lysate was incubated with rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG)-Sepharose. Bound proteins were eluted with MgCl2 and precipitated (37). Proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and identified by Western blotting using rabbit IgG (ICN) or anti-Yra1 antibody (56). Nap1-3HA was similarly isolated from a yra1-1 NAP1-3HA strain using anti-HA antibody (clone 12CA5; University of Virginia Hybridoma Center) coupled to protein A agarose (Pierce). Yra1-FLAG was isolated from Yra1-FLAG-expressing cells grown to an OD600 of 1.5 in YPD. Whole-cell extract was made as described above. Lysate was cleared and incubated with anti-FLAG agarose (Sigma). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and identified by Western blotting using anti-Nap1 (Santa Cruz) or anti-FLAG (Sigma) antibodies. Lysate was also similarly made from Yra1-FLAG cells fixed with 1% formaldehyde. The resin was washed with 50 mM- and 100 mM MgCl2-containing buffer (37), and complexes were eluted with a buffer containing 1 M MgCl2. Proteins were precipitated and heated to reverse cross-links. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and identified by Western blotting using anti-Nap1 and anti-FLAG antibodies.

Purification of recombinant proteins and in vitro binding assays.

Recombinant proteins were expressed and isolated as previously described (36). GST-Yra1-FLAG and GST-Yra1 were purified with glutathione Sepharose (Amersham). The GST tag was cleaved from GST-Yra1-FLAG with thrombin (Sigma). In vitro binding assays were performed as previously described using anti-FLAG agarose (Sigma) (36).

In vitro plasmid supercoiling assays.

Plasmid supercoiling assays using recombinant Nap1, GST, and GST-Yra1 were performed as previously described (35).

ChIP assays and real-time PCR.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as previously described with the following changes (5). Briefly, formaldehyde-fixed cells were broken with 0.5-mm glass beads in 150 mM NaCl lysis buffer. Sheared chromatin was cleared of nonspecific binding activity with IgG-Sepharose. Immunoprecipitations were carried out with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma) coupled to protein G-agarose (Pierce), anti-RNAP II antibody (8WG16; Covance) coupled to protein A-agarose, or anti-HA antibody coupled to protein A agarose. Antibody-coupled agarose was blocked with 150 mM NaCl lysis buffer-10% bovine serum albumin. Background control ChIP was carried out with blocked agarose incubated without antibody. Prior to elution, immune complexes were washed with 150 mM NaCl lysis buffer, wash buffer, and Tris-EDTA. Oligonucleotide sets were designed to amplify ADH1 (146 to 372 and 935 to 1271), PHO5 (863 to 960), or the GAL1 upstream activation sequence (UAS) (−482 to −330) (positions are relative to the translational start site) or were previously described (1, 23, 24). Real-time PCR was performed using Sybr green (Invitrogen) and Taq polymerase (Roche) or SensiMix Plus Sybr and fluorescein (Quantace) with a MiniOpticon real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad). All experiments were performed in duplicate. Real-time PCRs with all primer pairs were performed in triplicate for each sample.

Reverse transcription real-time PCR.

To measure PHO5 transcript levels, early log-phase cultures were induced in phosphate-free medium, and total RNA was obtained after 0, 4, and 8 h with hot acidic phenol and chloroform extraction. cDNA was generated with SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed with oligonucleotide pairs for PHO5 (863 to 960) and ACT1 (699 to 851) and Sybr green at conditions near 100% PCR efficiency for both oligonucleotide sets. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to determine relative expression, with ACT1 signal serving as the reference (28).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Cells were incubated for 2 h at the indicated temperatures (see Fig. 2). mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization with a Cy3-labeled poly(dT)50 probe was carried out as previously described (16). Nuclei were visualized with the DNA stain Hoechst 33342.

FIG. 2.

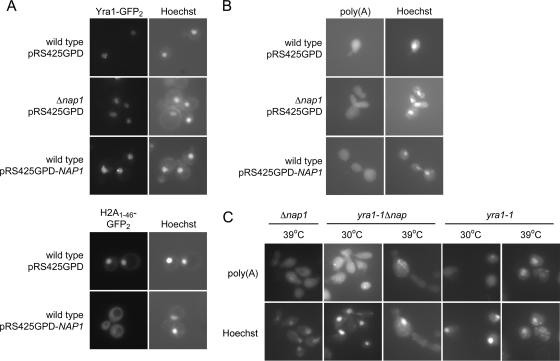

Nap1 is not essential for Yra1 nuclear import and Yra1-mediated mRNA export. (A) pYra1-GFP2 or pH2A1-46-GFP2 was expressed in wild-type or Δnap1 cells cotransformed with pRS425GPD or pRS425GPD-NAP1 and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. The coincident Hoechst images are shown. (B) Wild-type or Δnap1 cells were transformed with pRS425GPD or pRS425GPD-NAP1. mRNA localization was determined by poly(A) FISH using cells fixed at 30°C. The coincident Hoechst images are shown. (C) mRNA was localized by poly(A) FISH as described above, using strains of the indicated genotypes, after incubation at the indicated temperatures.

Microscopy.

Microscopy of GFP-expressing cells was performed using a Nikon Microphot-SA microscope (Melville, NY), and images were captured using OpenLab software (Improvision, Lexington, MA) with a ×100 objective as previously described (35). Cells were photographed using identical exposure settings, and all image manipulation was performed identically using Adobe Photoshop. The cell wall chitin of cells fixed with 1% formaldehyde was stained with 1 mg/ml calcofluor white (Sigma).

Acid phosphatase activity assays.

Cells were incubated in complete synthetic medium (CSM) plus 2% dextrose to an OD600 of 0.4. Cells were pelleted and induced in CSM-phosphate plus 2% dextrose and 1 g/liter KCl for the times indicated. Acid phosphatase assays were performed as previously described and were measured in Miller units (38). Statistically significant differences were determined using a two-tailed paired t test (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

mRNA export factor Yra1 interacts directly with Nap1.

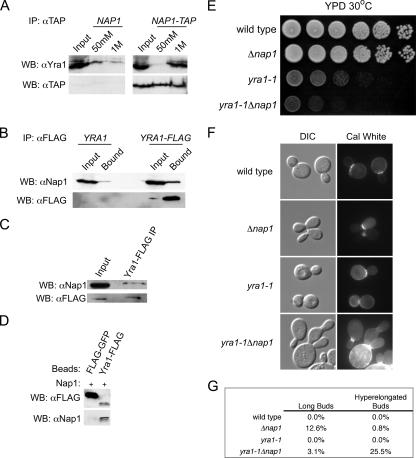

We wanted to test whether the TREX complex component Yra1 regulates the function of Nap1. Large-scale affinity purification experiments suggested that Yra1 interacts with Nap1, and we verified this interaction (14, 20, 25). We isolated Nap1-TAP or Yra1-FLAG from whole-cell extracts. Western blotting indicated that Yra1 and Nap1 specifically coimmunoprecipitated with the tagged proteins, compared to control experiments using untagged strains (Fig. 1A and B). To further confirm this interaction, we also made whole-cell extracts from Yra1-FLAG-expressing cells after formaldehyde fixation. Yra1-FLAG-containing complexes were immunoisolated, and after reversal of cross-links, we confirmed the presence of Nap1 by Western blotting (Fig. 1C). We also determined that the interaction was direct by performing an in vitro binding assay with recombinant Nap1 and Yra1-FLAG (Fig. 1D). Having established a physical interaction between Yra1 and Nap1, we also tested whether there is a functional relationship by examining the growth of a double mutant strain. YRA1 is essential, and a strain with a temperature-sensitive allele, yra1-1, and a concomitant deletion of NAP1 was generated. Strains expressing yra1-1 have a moderate growth defect at 23°C and complete growth impairment at 37°C (50). Interestingly, we observed that yra1-1Δnap1 cells grew slower at a semipermissive temperature than yra1-1 cells (Fig. 1E). We also compared bud morphology of yra1-1Δnap1 cells to those of a Δnap1 strain. A proportion of Δnap1 cells display a bud morphology defect where the daughter bud develops with impaired isotropic growth, resulting in elongated buds (21). We observed this phenotype for approximately 13% of cells in this background (Fig. 1F and G). Surprisingly, an asynchronous population of yra1-1Δnap1 cells grown at room temperature produced buds that were more aberrant than those observed for Δnap1 cells (Fig. 1F). The buds of the double mutants were longer than those of Δnap1 cells, and calcofluor white staining of cell wall chitin revealed that the double mutants had a cytokinetic defect. Typically, the daughter bud failed to undergo cytokinesis and initiated a third generation bud, distal from the mother bud neck (Fig. 1F). This observation is similar to that for cells with deletions of the DNA replication checkpoint factors (10). The hyperelongated morphology was observed for approximately 26% of yra1-1Δnap1 cells, compared with a frequency of <1% for Δnap1 cells, yra1-1 cells, or an isogenic wild-type strain (Fig. 1G). These data indicate that Yra1 and Nap1 share overlapping functions within the cell, and we hypothesized that yra1-1Δnap1 cells may have defects in the transcription of factors necessary for bud development and cytokinesis.

FIG. 1.

Nap1 interacts directly with Yra1. (A) Whole-cell lysates from a Nap1-TAP (right panel) and an untagged strain (left panel) were incubated with IgG Sepharose. Interacting proteins were eluted with the indicated MgCl2 concentrations. Yra1 and Nap1-TAP were detected by Western blotting (WB). (B) Whole-cell lysates from a Yra1-FLAG-tagged (right panel) and an untagged strain (left panel) were incubated with anti-FLAG resin. Bound proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (C) Yra1-FLAG was immunoisolated from whole-cell extract made from formaldehyde-fixed cells. Coprecipitating Nap1 was detected by Western blotting. (D) Immobilized FLAG-GFP or Yra1-FLAG (250 nM) was incubated with Nap1 (250 nM). Complexes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with FLAG and Nap1 antibodies. (E) Strains of the indicated genotype were equalized, spotted at 10-fold serial dilutions, and grown on YPD plates at 30°C for 2 days. (F) Strains of the indicated genotype were stained with calcofluor white (Cal White) and visualized by fluorescence and differential interference contrast microscopy. (G) The frequency of long and hyperelongated buds relative to normal buds in asynchronous populations of cells was determined. The length of long buds was approximately greater than the width, but not did not exceed the mother cell diameter. The length of hyperelongated buds was approximately greater than both the bud width and mother cell diameter. A minimum of 175 cells were characterized.

Nap1 does not mediate the nuclear import of Yra1 and is not essential for Yra1-mediated mRNA export.

If Nap1 and Yra1 share a common function, then Nap1 could play a role in transcription, mRNA export, or the nuclear import of Yra1. Yra1 nuclear import is mediated primarily by the karyopherins Kap121 and Kap123 (55). We tested the effect of deletion and overexpression of NAP1 on the subcellular localization of Yra1. Yra1-GFP2 was expressed in Δnap1 strains or in cells transformed with a NAP1 overexpression plasmid, and we observed that alteration of Nap1 levels did not result in decreased nuclear localization of Yra1-GFP2 (Fig. 2A). As a control, we showed that overexpression of NAP1 leads to the cytoplasmic mislocalization of a histone H2A-nuclear localization signal reporter (Fig. 2A). Therefore, the physical and genetic interaction of Nap1 and Yra1 appears unrelated to the nuclear import of Yra1, and we next asked if Nap1 functioned with Yra1 in mRNA export.

Cells expressing the yra1-1 allele at a nonpermissive temperature display a defect in mRNA export (50). We performed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to poly(A) mRNA to examine Nap1's role in mRNA export. We tested whether NAP1 overexpression or deletion leads to the accumulation of poly(A) RNA in the nucleus, and we found that neither condition affected the export of mRNA (Fig. 2B). As expected, poly(A) mRNA accumulated in the nucleus of yra1-1 cells shifted to a nonpermissive temperature (Fig. 2C). We next addressed whether Δnap1 exacerbates the yra1-1-dependent mRNA export defect at a semipermissive temperature (30°C). Intriguingly, Δnap1 did not appear to exacerbate the export phenotype, despite the growth defect observed (Fig. 2C). This suggests that Nap1 is not affecting the global nuclear export of transcripts regardless of expression level, although Nap1 nuclear functions are physically tied to Yra1.

NAP1 genetically interacts with MEX67 and the THO complex.

Since we postulated a role for Nap1 during transcription, we tested if Nap1 interacts with the essential mRNA export factor Mex67. Mex67 interacts with TREX complex components and is recruited to transcribing genes (15). While proteomic screens have not revealed a physical association between Nap1 and Mex67, we asked if NAP1 interacted genetically with MEX67, given the functional and physical overlap between Mex67 and Yra1. We used strains expressing the mex67-5 allele, which confers temperature sensitivity and an mRNA export defect at 37°C (48). We examined the growth and morphology of mex67-5 and mex67-5Δnap1 cells. Strikingly, we detected a strong growth defect in mex67-5Δnap1 cells at 30°C, which was not evident in mex67-5 cells (Fig. 3A). Moreover, a proportion of mex67-5Δnap1 cells grown at 25°C also displayed the hyperelongated long bud phenotype seen before in yra1-1Δnap1 cells (Fig. 3B). This morphology was observed for approximately 12% of mex67-5Δnap1 cells, compared to a frequency of <1% for mex67-5 cells, Δnap1 cells, or an isogenic wild-type strain (Fig. 3C and 1F). This demonstrated that there is a genetic interaction between NAP1 and MEX67 and that Nap1 functionally interacts with another mRNA export component. These results support the hypothesis that mRNP biogenesis and chromatin remodeling are linked.

FIG. 3.

NAP1 functionally interacts with MEX67 and the THO complex. (A) Strains of the indicated genotype were equalized, spotted at 10-fold serial dilutions, and grown on YPD at 30°C for 2 days. (B) The indicated cell types were stained with calcofluor white (Cal White) and visualized by differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence microscopy. (C) The frequency of long and hyperelongated buds relative to normal buds in asynchronous populations of the indicated cells was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 1. A minimum of 225 or 160 cells were characterized for the upper or lower tables, respectively.

We surmised that Nap1 might also interact with other components of the TREX complex, such as the THO complex. While there is no evidence of a physical Nap1-THO complex interaction, we anticipated a genetic interaction if Nap1 is linked to transcription elongation and export. A microscopic examination revealed that the Δmft1Δnap1 and Δthp2Δnap1 double deletions also display a cytokinetic defect (data not shown). The morphology observed is similar to that observed with yra1-1Δnap1 cells and was seen in approximately 5% of both Δmft1Δnap1 and Δthp2Δnap1 strains (Fig. 3C). The defect was not observed in a parallel comparison of the isogenic wild-type or the single deletions strains (Fig. 3C). This demonstrates a genetic interaction between NAP1 and MFT1 and THP2. Cells lacking THO complex components have defects in growth and mRNA export at 37°C (8, 51). Δmft1Δnap1 and Δthp2Δnap1 cells did not appear to have a growth defect at 37°C relative to the single deletion cells (data not shown), and as with yra1-1Δnap1 cells, we found that the loss of NAP1 did not markedly exacerbate the THO complex-dependent mRNA export defect at 37°C (data not shown). Collectively, this indicates that NAP1 and the TREX complex share a genetic interaction, suggesting overlapping functions.

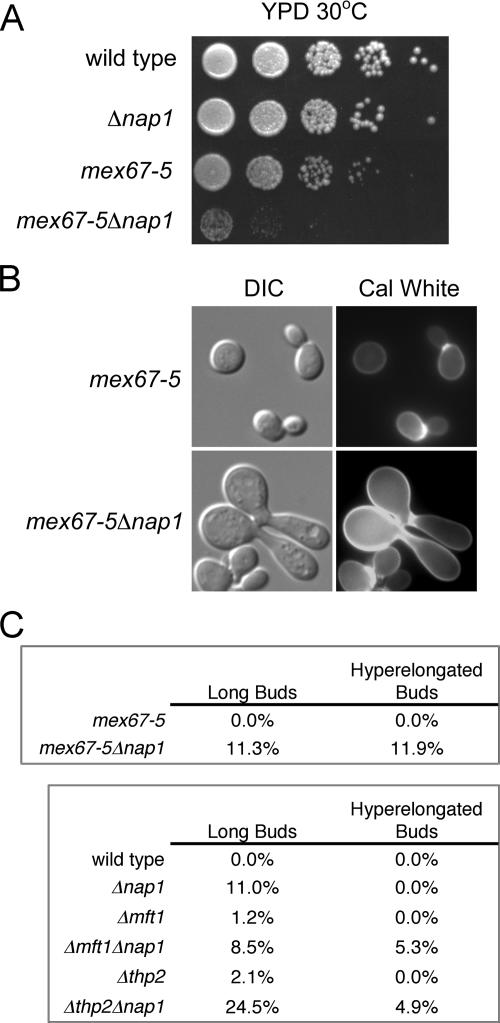

NAP1 deletions are sensitive to transcriptional stress and DNA damage.

Nap1 therefore appeared to function with TREX complex components and with the associated protein Mex67. Having ruled out potential roles in the nuclear import of Yra1 or a general role in mRNA export, we decided to test whether Nap1 functioned in transcription. Cells with defects in transcription components are often sensitive to 6-azauracil (6-AU), which affects the RNAP II elongation rate and processivity (32). Thus, we determined whether our double mutant strains were more sensitive to 6-AU than the relevant single mutants. Serial dilutions of yra1-1Δnap1 cells, mex67-5Δnap1 cells, the single mutants, and the isogenic wild-type strain were spotted onto plates containing 6-AU and incubated at 25°C or 30°C. Surprisingly, at 30°C, Δnap1 cells were sensitive to 6-AU, indicating that Nap1 has an important function during transcription elongation (Fig. 4A). This is the first genetic link between Nap1 and a nuclear function, such as transcription, that has been demonstrated in vivo. Moreover, the sensitivity to 6-AU was exacerbated in mex67-5Δnap1 cells even after 3 days of growth at 30°C (Fig. 4A). yra1-1Δnap1 cells were also more sensitive to 6-AU at 25°C than either yra1-1 or Δnap1 cells alone (Fig. 4B). This result indicates that Nap1 histone chaperone activity and TREX complex functions are indeed connected.

FIG. 4.

nap1 mutants are sensitive to transcriptional stress and DNA damage. Strains of the indicated genotype were equalized and spotted at 10-fold serial dilutions and grown (A) on plates lacking uracil (−Ura) with or without 100 μg/ml 6-azauracil (6-AU) and incubated for 3 days at 30°C, (B) as described for panel A except the plates were incubated for 4 days at 25°C, and (C) on CSM plates with or without 1 μM 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4-NQO) for 4 days at 25°C.

Deficiencies in transcription elongation can result in initiation from cryptic start sites and increased susceptibility to genomic instability (12, 33, 54). Cells lacking the histone chaperone Asf1 have increased sensitivity to cisplatin-induced DNA damage (42). Additionally, Mex67-TREX complex mutations negatively affect the survival of Δrad7 cells after UV irradiation, indicating their importance in nucleotide excision repair (12). The UV-mimetic 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide (4-NQO) increases the frequency of transcription-associated recombination (13). We tested whether yra1-1Δnap1 and mex67-5Δnap1 cells were more susceptible to DNA damage by 4-NQO. Serial dilutions of the mutants and the isogenic wild-type strain were spotted on plates containing 4-NQO and incubated at 25°C (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, Δnap1 cells were mildly sensitive to 4-NQO, indicating that Nap1 facilitates DNA damage repair mechanisms. As with 6-AU, both yra1-1Δnap1 and mex67-5Δnap1 strains were more sensitive to 4-NQO than the single mutants. This result indicates that the expression of mutant alleles of mRNA export factors in conjunction with Δnap1 makes cells more susceptible to DNA damage. This suggests that Nap1 is functionally linked to transcript elongation and export.

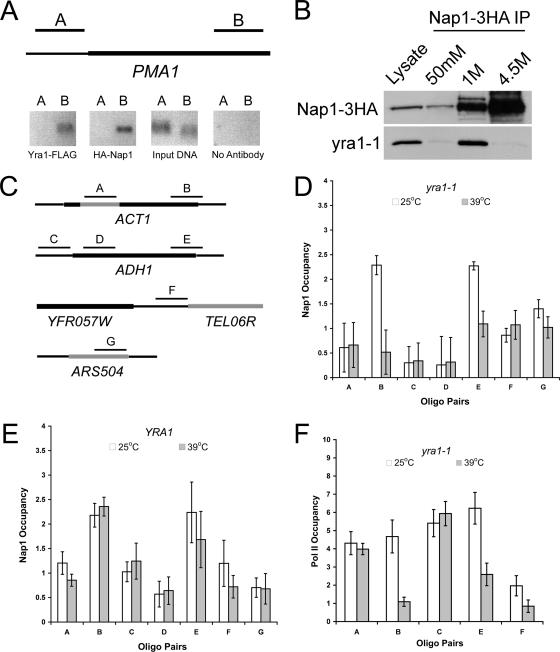

Yra1 recruits Nap1 to active sites of transcription in vivo.

Based on the previous data, we asked whether Nap1 is physically associated with actively transcribed genes. A direct association of Nap1 with chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae has not been demonstrated in vivo, and we tested this using ChIP. Since we found that Nap1 and TREX complex functions overlapped, we tested genes to which Yra1 is known to be recruited. In S. cerevisiae, TREX complex components are associated with actively transcribed ORFs with occupancy increasing from the 5′ to the 3′ end, and not in intergenic regions (1, 22, 51, 56). Using primers to the constitutively active gene PMA1, we confirmed that Yra1 is associated with this ORF and not the promoter region (Fig. 5A). We found that Nap1 displays a similar chromatin association pattern at PMA1. This result indicates that Nap1 is associated with chromatin in S. cerevisiae, and it also suggests that Yra1 and Nap1 are recruited to the same regions.

FIG. 5.

Nap1 recruitment to sites of active transcription is Yra1 dependent. (A) Chromatin was isolated from a Δyra1 Δnap1 strain expressing plasmids encoding Yra1-FLAG and HA-Nap1. Yra1 and Nap1 occupancy at the PMA1 promoter and ORF was determined by ChIP assay with conventional PCR using oligonucleotide pairs to the indicated regions of PMA1. The assay was also performed without antibody as a negative control. (B) yra1-1 was coimmunoprecipitated from whole-cell extracts with Nap1-3HA and detected by Western blotting. (C) Nap1 recruitment to the ACT1 and ADH1 ORFs and intergenic regions was tested by ChIP assay using the indicated oligonucleotide pairs. (D) Nap1 ChIP assays quantified by real-time PCR were performed with a Δyra1 Δnap1 strain expressing yra1-1 and HA-Nap1. Cells were grown for 2 h at 25°C or 39°C prior to fixation as indicated. Occupancy is expressed as the log2 difference (n-fold) between specific and background IP signals normalized to input, displayed as the mean and average standard deviation from two independent experiments. Oligo, oligonucleotide. (E) Nap1 ChIP assays quantified by real-time PCR were performed exactly as for panel D with a YRA1 Δnap1 strain expressing HA-Nap1. (F) RNAP II (Pol II) ChIP assays quantified by real-time PCR as for panel D were performed from a Δyra1 strain expressing yra1-1 exogenously. Means and standard deviations are indicated.

Due to the physical interactions of Nap1 with histones and chromatin remodeling complexes, we tested its association with transcribed and nontranscribed regions by ChIP and real-time PCR with the yra1-1 strain. Growing this strain at the permissive and nonpermissive temperatures allowed us to test if Nap1 recruitment to chromatin was dependent on Yra1. We confirmed that Nap1 interacted with yra1-1 by coimmunoprecipitation of yra1-1 with Nap1-3HA (Fig. 5B). We tested if Nap1 occupies coding regions of the constitutively active genes ACT1 and ADH1, as Yra1 is associated with these reading frames (1, 22). We also examined Nap1 occupancy at the ACT1 intron, ADH1 promoter, and two nontranscribed regions, ARS504 and TEL06R (Fig. 5C). The ChIP assays were performed with yra1-1 cells that had been incubated for 2 h at 25°C or 39°C prior to fixation. We determined occupancy by calculating the log2 differences (n-fold) in threshold cycles between the Nap1 IP and a background control IP. These values were then normalized to the amount of input DNA for each region tested. Using this method, we were able to determine if Nap1 occupancy changes in transcribed and nontranscribed regions in a Yra1-dependent manner, anticipating only changes in ORFs. We observed Nap1 occupancy above background levels at all regions tested (Fig. 5D). Importantly, this result indicates that Nap1 occupies a variety of chromatin regions. We also observed that while Nap1 was highly enriched at the 3′ end of the ACT1 and ADH1 ORFs, this occupancy was reduced when the cells were incubated at 39°C (Fig. 5D). Assays performed with wild-type cells revealed no substantial differences in occupancy at 25°C or 39°C (Fig. 5E). This suggested that Yra1 is necessary for the recruitment of Nap1 to the ORF of ACT1 and ADH1. Conversely, we found that Δnap1 had no affect on Yra1 recruitment to an ORF (data not shown).

We next tested if loss of functional Yra1 affects RNAP II association with reading frames of actively transcribed genes. We performed RNAP II ChIP assays from yra1-1 cells grown at 25°C or 39°C prior to fixation and determined occupancy by real-time PCR. At the elevated temperature, we observed that RNAP II was still recruited to the ADH1 promoter and is still associated with the 5′ end of ACT1 (Fig. 5F). However, we found decreased RNAP II association with the 3′ ends of the ACT1 and ADH1 ORFs at the high temperature. This result correlates with the observation that cells with deletions of THO complex components have defects in RNAP II processivity (32). Our data suggest that Yra1 may be mediating RNAP II processivity in a manner similar to that of other TREX complex components and also by directly recruiting the histone chaperone Nap1. We also cannot rule out the possibility that RNAP II may be responsible for recruitment of Yra1 and Nap1 to coding regions.

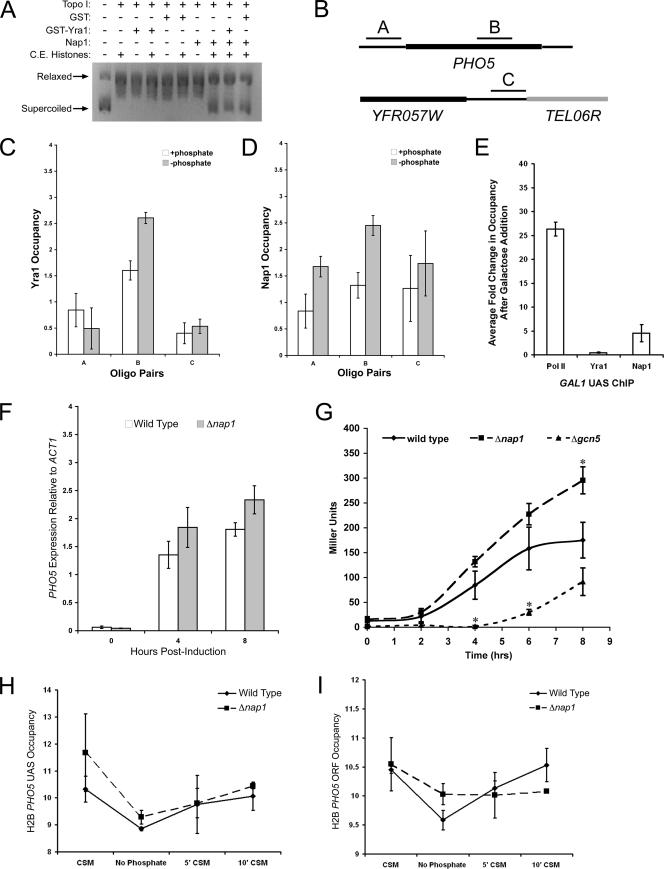

Nap1 histone chaperone activity influences transcription of an active gene.

Nap1 recruitment by Yra1 to an actively transcribed region indicates that it may function in chromatin disassembly, reassembly, or both. In an in vitro transcription system, Nap1 modulates histone mobilization from a DNA template (26). Before determining a role for Nap1 during transcription in vivo, we first verified that Yra1 is not inhibitory to Nap1 histone chaperone activity by using a plasmid supercoiling assay. We performed the assay with equal molar ratios of Nap1 and either GST or GST-Yra1. We observed that Nap1 retains histone deposition function in the presence of Yra1 (Fig. 6A). To determine if Nap1 functions are a requisite for efficient transcription in vivo, we examined the role of Nap1 in the transcription of the repressed acid phosphatase Pho5. We first verified that the nuclear import of the transcription factor Pho4, which binds to the PHO5 UAS, was not inhibited in a Δnap1 strain (data not shown). We next determined if Yra1 or Nap1 was associated with PHO5 before or after the induction of transcription by phosphate starvation by ChIP assay. Yra1 was recruited to the PHO5 ORF and not to intergenic regions after phosphate starvation (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, the occupancy of Nap1 at the promoter region and within the coding region increased substantially following induction of transcription (Fig. 6D). In contrast, there was no substantial increase at a telomeric region (Fig. 6D). This indicates that Yra1 may recruit Nap1 to the PHO5 coding region during transcription, as we observed at a constitutively active gene. In addition, we observed an increase in Nap1 occupancy at the promoter region, which is consistent with recent evidence that the Saccharomyces pombe homologs of Nap1 and Chd1p remodel nucleosomes at promoters (53). Nap1 also promotes the deposition of the histone variant H2A.Z in vitro, which is known to be deposited at the repressed PHO5 promoter (39, 44). Therefore, the recruitment of Nap1 to the promoter after induction is likely independent of Yra1.

FIG. 6.

The histone chaperone Nap1 regulates PHO5 transcription by mediating nucleosome mobilization. (A) Nap1 histone chaperone activity in the presence of Yra1 was tested by a plasmid supercoiling assay using recombinant Nap1 (500 nM) and GST or GST-Yra1 (500 nM). Topo I, topoisomerase I; C.E., chicken erythrocyte. (B) Yra1 and Nap1 occupancy at the PHO5 promoter, ORF, and a telomeric region was determined by ChIP assay with real-time PCR using the indicated primer pairs. Chromatin was prepared from a Δyra1Δnap1 strain expressing Yra1-FLAG and HA-Nap1 exogenously. Cells were grown in CSM-histidine at 30°C to an OD600 of ≈0.8 and were transferred to synthetic medium lacking phosphate for 4 h prior to fixation. Yra1 (C) or Nap1 (D) occupancy was determined as before. +phosphate, CSM-histidine with phosphate; −phosphate, CSM-histidine lacking phosphate; Oligo, oligonucleotide. (E) RNAP II (Pol II), Yra1, and Nap1 recruitment to the GAL1 UAS was tested by ChIP assays using real-time PCR performed with the cells used for panels C and D. Cells were grown to log phase in 2% raffinose or 2% raffinose followed by 2 h in 2% galactose. Data are expressed as changes (n-fold) in occupancy following galactose induction. Means and standard deviations from two independent experiments are shown. (F) RNA was isolated from wild-type and Δnap1 cells, and the expression of PHO5 transcript relative to ACT1 transcript was determined by reverse transcription real-time PCR. (G) Acid phosphatase activities of wild-type (BY4741), Δnap1, and Δgcn5 cells were measured following phosphate deprivation. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) relative to wild-type activity are indicated by an asterisk. H2B occupancy at the PHO5 promoter (H) and within the ORF (I) was determined by ChIP assay with real-time PCR. Chromatin was isolated from FLAG-H2B and FLAG-H2BΔnap1 cells prior to and during phosphate starvation (CSM, no phosphate) and 5 and 10 min after phosphate reintroduction (5′ CSM, 10′ CSM). Occupancy is expressed as the log2 difference (n-fold) between specific IP signal (UAS or ORF) and background normalized to input and TEL06R and displayed as the average and standard deviation from two independent experiments.

We confirmed that recruitment of Nap1 to promoter regions is dependent on transcription and independent of Yra1 by examining Nap1 recruitment to the GAL1 UAS. We performed RNAP II, Nap1, and Yra1 ChIP assays with real-time PCR from cells grown to log phase in raffinose or galactose. We determined the change (n-fold) in occupancy at the GAL1 UAS following galactose induction. As previously reported, RNAP II recruitment to the GAL1 promoter increases upon induction (33), whereas Yra1 is not recruited (Fig. 6E). We observed that Nap1 is recruited to the GAL1 promoter, and recruitment occurs independently of Yra1 (Fig. 6E). This further supports the idea that Nap1 has chromatin-related functions that are independent of the TREX complex.

Recruitment of Nap1 to the promoter and coding region of PHO5 indicates that it may function in both the transcription initiation and the elongation phases. We tested this by measuring PHO5 transcript levels in Δnap1 cells. We isolated RNA from log-phase Δnap1 and isogenic wild-type cells after 0, 4, and 8 h of phosphate starvation. The amount of PHO5 transcript was determined and normalized to that of ACT1 by real-time PCR. After 8 h of induction, we saw a small but reproducible increase in the amount of PHO5 transcript produced by Δnap1 cells relative to wild-type cells (Fig. 6F). This indicates that Nap1 may be functioning during transcription elongation and is not a requisite for regulating initiation. If Δnap1 resulted in hyperinitiation, we would have expected higher transcript levels prior to induction, and if Δnap1 led to hypoinitiation, we would have expected lower levels after induction. These findings are also consistent with previous work that indicates that Δnap1 does not result in hyper- or noninitiation of PHO5 transcription (17). As Δnap1 leads to an increase in the PHO5 transcript, we propose that Nap1 has an overall negative affect on elongation and is functioning in the reconstitution of template chromatin.

To further investigate whether Nap1 was functioning during the elongation phase of transcription, we also measured the acid phosphatase activity from Δnap1, Δgcn5, and wild-type cells. Gcn5 promotes transcription initiation of PHO5 and acid phosphatase expression in Δgcn5 cells is delayed (6). As expected, we observed that the activity curve for Δgcn5 cells was significantly shifted to the right after induction, suggesting a delay in initiation compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 6G). In contrast, the phosphatase activity in Δnap1 cells was significantly greater than that for the isogenic wild type by eight hours (Fig. 6G). However, the curve was not shifted to the left or right, suggesting that Nap1 is not a requisite for initiation. Only the plateau level of the curve changed with Δnap1 cells and not the derivative, which supports the previous results and is consistent with the model that Nap1 functions during transcription elongation. Taken together, these results indicate that Nap1 appears to have an overall negative affect on PHO5 transcription, raising the possibility that the major role of Nap1 is in the reassembly of nucleosomes.

To investigate whether Nap1 is important for chromatin reassembly during the transcription of an ORF, we performed H2B ChIP assays. Cells expressing FLAG-H2B were grown in CSM to early log phase and then starved of phosphate for 4 h to induce PHO5 expression. The cells were returned to phosphate-containing medium (CSM) for 5 or 10 min, whereupon PHO5 should be repressed. Chromatin was isolated from aliquots of cells fixed prior to phosphate starvation, after starvation, and 5 or 10 min after phosphate readdition. We determined H2B occupancy at the PHO5 promoter, PHO5 reading frame, and TEL06R by real-time PCR. The log2 changes (n-fold) in H2B occupancy over background were normalized to input DNA signal and to PCRs using the TEL06R primer pair. As expected, there was no substantial difference between wild-type and Δnap1 cells in H2B mobilization at the PHO5 promoter (Fig. 6H). However, after 10 min of phosphate readdition, there was a difference in H2B occupancy in the PHO5 ORF. H2B levels were still reduced in the Δnap1 strain, while H2B occupancy in wild-type cells returned to near prestarvation levels (Fig. 6I). This result further supports the hypothesis that Nap1 is important for nucleosome rearrangement during transcription elongation and likely plays an important role in efficient chromatin reassembly.

DISCUSSION

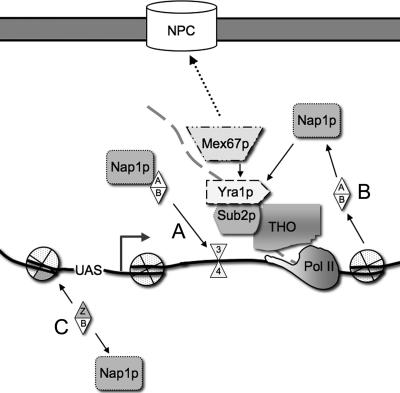

Transcription is regulated both by the recruitment of RNAP II to promoters and by the recruitment of factors that regulate transcription elongation (45). Many of these factors alter chromatin structure, allowing RNAP II to move through the chromatin barrier; others recruit proteins necessary to complete mRNP biogenesis (27, 45). Here, we show that Nap1 associates with chromatin and is necessary for normal transcription of an activated gene. We propose that Nap1 plays an important role as a histone chaperone during transcription elongation, and our evidence suggests that Nap1 functions in chromatin reassembly after the passage of the polymerase. Nap1 has genetic and physical interactions with components of the RNA TREX complex as well as with the export factor Mex67. Our results suggest a model whereby the TREX complex helps target Nap1 to elongating genes, where it acts as a chromatin assembly factor. Nap1 therefore represents a new connection between the chromatin remodeling and mRNP biogenesis machineries (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Model of Nap1 function during transcription. The TREX complex component Yra1 directly recruits Nap1 to a site of active transcription. (A) Nap1 facilitates the reincorporation of H2A/H2B dimers and octamer reassembly on the open template following RNAP II (Pol II) progression. (B) Nap1 may also function in H2A/H2B disassembly preceding RNAP II. (C) Nap1 also mediates histone mobilization at other regions, such as the promoter in Yra1-independent mechanisms.

We showed that combined loss of NAP1 and deficiencies in TREX complex components, or MEX67, led to exacerbated growth and bud morphology defects. The genetic interaction with TREX complex components and Mex67 suggested that Nap1 may share an important role in transcription or mRNP maturation. Nap1 interacts directly with Yra1, but so far we have no evidence that there is a direct physical interaction with the other components. There is no evidence that Nap1 is directly contributing to mRNA export, as deletion or overexpression of NAP1 did not result in changes in global mRNA export. While Nap1 is a nuclear shuttling protein, it is predominantly in the cytoplasm at steady state (36). A proportion of Nap1 is found at the incipient bud site and bud neck, and loss of Nap1 leads to a long bud phenotype in a proportion of cells, suggesting a delay in the activation of the mitotic cyclin Clb2. We considered the possibilities as to why loss of Nap1 and different TREX complex components would lead to a dramatic exacerbation of the elongated bud phenotype, as well as growth defects. We cannot exclude the possibility that in the Δnap1 strain, specific loss of Nap1 from the bud neck is responsible for the bud morphology defect, and this phenotype is exacerbated in the double mutants by the reduction of transcripts that are also important for G2/M progression. However, we favor the model in which Nap1 nuclear functions also regulate bud morphology. For example, Yra1 and Mex67 are physically associated with transcripts involved in cell wall development and other metabolic processes, and the concomitant absence of Nap1 and these proteins may affect the transcription of important G2/M regulators (16). It has also been shown that Rad53, Tel1, and Mec1, components of the DNA damage repair pathway, are requisites for proper bud formation (10). Interestingly, deletion of these components results in hyperelongated buds that resemble those of the yra1-1Δnap1 strain, giving further evidence that these buds are the product of defects in chromatin-templated processes.

A hallmark of genes involved in transcription elongation is the sensitivity of corresponding mutants to 6-AU and DNA damage (12, 32, 42). Consequently, we show that not only are Δnap1 cells are sensitive to 6-AU but also this effect is compounded for both yra1-1Δnap1 and mex67-5Δnap1 cells. This indicates that the Nap1 histone chaperone activity and TREX complex/Mex67 mRNP functions are linked, providing further evidence that intersecting nuclear functions are responsible for the phenotypes observed. Additionally, it has been shown that yra1-1 and mex67-5 cells are more susceptible to genomic instability (19). The observation that yra1-1Δnap1 and mex67-5Δnap1 cells are more sensitive to DNA damage by 4-NQO than either single mutant also supports our hypothesis. The double mutants likely have defects in nucleosome positioning, histone mobilization, and transcription elongation. The net effect of the defects likely results in abrogated DNA damage repair and genomic instability.

Many nuclear functions have been proposed for Nap1, and different chromatin assembly and disassembly activities have been observed in vitro (40, 57). Remarkably, there has been no evidence in S. cerevisiae of Nap1 association with chromatin in vivo. Here, we demonstrate that S. cerevisiae Nap1 is associated with chromatin. Importantly, we determined that Nap1 was associated with some of the same ORFs as Yra1, in addition to associating with nontranscribed regions and promoters. Furthermore, using a yra1-1 mutant strain grown at the restrictive temperature, we showed that Nap1 recruitment to these regions appeared to be dependent on Yra1. Previous studies have indicated that the yra1-1 mutant has five amino acid substitutions, with F223S being critical for the temperature-sensitive phenotype. This mutant is slightly overexpressed at 23°C, indicative of an inability to autoregulate expression (41, 50). Additionally, this mutation lies within a region important for binding Mex67 and the TREX complex component Sub2 (49, 55). We showed that at the permissive temperature, this mutant was still able to interact with Nap1. At 30°C, yra1-1 mutant cells are also more prone to transcription-associated recombination defects (19). The precise mechanism whereby this mutation leads to lethality at 37°C is not known. It is possible that the protein is less stable, or that the protein no longer interacts with chromatin, or that the protein is unable to interact with a subset of binding partners, particularly Sub2 and Mex67. The concomitant loss of Nap1 from the same regions of chromatin at 37°C is likely due to the loss of Yra1 function via one of the above mechanisms. We determined that that RNAP II association with the ORF also decreased in a Yra1-dependent fashion. This is not surprising, as cells lacking the TREX complex component Hpr1 demonstrate a loss of association of RNAP II with the 3′ end of ORFs, and it was proposed that the absence of Hpr1 impairs RNAP II processivity (32). We cannot rule out the possibility that RNAP II also coordinates Nap1 recruitment to ORFs. In this model, Nap1 could be recruited to both promoters and ORFs by the RNAP II-dependent disruption of chromatin, where it would be involved in replacing nucleosomes displaced by transcription. However, in this model, the observed role of Yra1 in Nap1 recruitment is unclear, unless it is an indirect effect of transcription not proceeding into the downstream regions of the gene. However, because of the direct physical interaction reported here, as well as the genetic interactions with YRA1 and other TREX complex components, we favor the model in which Yra1 is recruiting Nap1 to specific ORFs.

Nap1 has diverse functions in the cell; however, its precise role in nucleosome assembly in vivo is largely uncharacterized. One function that may be dependent on Nap1-mediated nucleosome rearrangement is chromatin remodeling at an activated promoter. Our data demonstrate that PHO5 and GAL1 are examples of genes where Nap1 is recruited to the promoter regions upon transcription activation. Moreover, Nap1 recruitment to the promoter is occurring independently of Yra1. This suggests that in vivo, Nap1 also has chromatin functions that are distinct from Yra1 and are regulated by other mechanisms. The function of Nap1 at the promoter is likely also tied to nucleosome mobilization. The eviction and incorporation of histones at the PHO5 promoter occurs in trans and can be mediated by the histone chaperones Asf1, Hir1, and Spt6 as well as by the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex (2, 3, 24, 46). Our data show that Nap1 is required for normal transcription of PHO5, although measurements of mRNA levels, phosphatase activity assays, and H2B ChIP suggested that Nap1 is not a requisite for PHO5 transcription initiation. However, recruitment of Nap1 to promoter regions suggests that Nap1 is involved in chromatin remodeling of the promoter. Interestingly the S. pombe homologs of Nap1 and the ATP-dependent remodeling factor Chd1 have also recently been shown to be associated with both coding and nontranscribed regions. They are believed to cooperate to displace histones from promoters in vivo (53). One role for S. cerevisiae Nap1 at the PHO5 promoter could be in the mobilization of the H2A variant H2A.Z. This histone is poised at the repressed PHO5 promoter and then removed during activation (44). Nap1 and Chz1 are redundant histone chaperones for H2A.Z; therefore, the loss of NAP1 alone may not alter PHO5 transcription initiation (31, 34). The identification of Nap1 at chromatin regions independently of Yra1 raises the question of how Nap1 is targeted to the correct chromatin domain. We speculate that this may involve the SWR1 or other protein complexes, or possibly Nap1 itself, via recognition of different modifications within the histone N-terminal tails.

The occupancy with Yra1 at the PHO5 ORF, the modest changes in PHO5 transcript level and phosphatase activity observed for Δnap1 cells, and the delay in H2B redeposition during transcription repression suggest that Nap1 may also be important for chromatin remodeling during transcription elongation. Our data are consistent with the model whereby the net function of Nap1 is to facilitate nucleosome reassembly. This function is in contrast to the role of Nap1 with Chd1 in S. pombe, where it was shown to function in chromatin disassembly, suggesting that at specific chromatin domains, Nap1 may act both in assembly and disassembly (53). Asf1p has been shown to mediate both the eviction and the deposition of H3 during elongation, and both Spt6 and the FACT complex have chromatin reassembly activity (45, 47). We propose that Nap1 serves that same purpose for H2A/H2B dimers and that chromatin reassembly is important during elongation to prevent transcription initiation within the coding region. Nap1 interacts with histones directly but must be targeted to the correct chromatin domains. We propose a model whereby during elongation, Yra1 recruits Nap1 to the actively transcribed region where Nap1-mediated H2A/H2B mobilization occurs (Fig. 7). Nap1 may be either a histone acceptor and donor or an active participant in the disassembly and reconstitution phases during RNAP II progression. Given the redundancy of histone chaperones, Nap1 may facilitate disassembly reactions during elongation in concert with other factors. A likely mechanism for Nap1 histone chaperone activity during elongation would therefore also involve interactions with other factors, like Chd1, the RSC complex, or the FACT complex.

In summary, we present evidence that suggests that Nap1 functions in transcription elongation and that recruitment of Nap1 to some chromatin domains is dependent on the TREX complex. Furthermore, at an activated gene, Nap1 appears to be important for chromatin reassembly. Generally, factors involved in pre-mRNA processing are recruited by the RNAP II C-terminal domain, and the Yra1-Nap1 interaction would demonstrate a unique mechanism of recruitment of a histone chaperone to an actively transcribed gene (4). Thus, Nap1 represents a new connection between chromatin assembly and mRNP biogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ed Hurt, Erin O'Shea, Mary Ann Osley, and Françoise Stutz for reagents and the Pemberton lab for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a NIH research grant to L.F.P. (RO1 GM65385).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 January 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abruzzi, K. C., S. Lacadie, and M. Rosbash. 2004. Biochemical analysis of TREX complex recruitment to intronless and intron-containing yeast genes. EMBO J. 232620-2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adkins, M. W., S. R. Howar, and J. K. Tyler. 2004. Chromatin disassembly mediated by the histone chaperone Asf1 is essential for transcriptional activation of the yeast PHO5 and PHO8 genes. Mol. Cell 14657-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adkins, M. W., and J. K. Tyler. 2006. Transcriptional activators are dispensable for transcription in the absence of Spt6-mediated chromatin reassembly of promoter regions. Mol. Cell 21405-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguilera, A. 2005. Cotranscriptional mRNP assembly: from the DNA to the nuclear pore. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17242-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aparicio, O. 1999. Characterization of proteins bound to chromatin by immunoprecipitation from whole-cell extracts, p. 21.3.1-21.3.12. In R. B. F. M. Ausubel, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology, vol. 4. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbaric, S., J. Walker, A. Schmid, J. Q. Svejstrup, and W. Horz. 2001. Increasing the rate of chromatin remodeling and gene activation—a novel role for the histone acetyltransferase Gcn5. EMBO J. 204944-4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey, M., B. Li, and J. L. Workman. 2006. RSC exploits histone acetylation to abrogate the nucleosomal block to RNA polymerase II elongation. Mol. Cell 24481-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chavez, S., T. Beilharz, A. G. Rondon, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, J. Q. Svejstrup, T. Lithgow, and A. Aguilera. 2000. A protein complex containing Tho2, Hpr1, Mft1 and a novel protein, Thp2, connects transcription elongation with mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 195824-5834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins, S. R., K. M. Miller, N. L. Maas, A. Roguev, J. Fillingham, C. S. Chu, M. Schuldiner, M. Gebbia, J. Recht, M. Shales, H. Ding, H. Xu, J. Han, K. Ingvarsdottir, B. Cheng, B. Andrews, C. Boone, S. L. Berger, P. Hieter, Z. Zhang, G. W. Brown, C. J. Ingles, A. Emili, C. D. Allis, D. P. Toczyski, J. S. Weissman, J. F. Greenblatt, and N. J. Krogan. 2007. Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature 446806-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enserink, J. M., M. B. Smolka, H. Zhou, and R. D. Kolodner. 2006. Checkpoint proteins control morphogenetic events during DNA replication stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 175729-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finley, D., E. Ozkaynak, and A. Varshavsky. 1987. The yeast polyubiquitin gene is essential for resistance to high temperatures, starvation, and other stresses. Cell 481035-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaillard, H., R. E. Wellinger, and A. Aguilera. 2007. A new connection of mRNP biogenesis and export with transcription-coupled repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 353893-3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Rubio, M., P. Huertas, S. Gonzalez-Barrera, and A. Aguilera. 2003. Recombinogenic effects of DNA-damaging agents are synergistically increased by transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. New insights into transcription-associated recombination. Genetics 165457-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gavin, A. C., M. Bosche, R. Krause, P. Grandi, M. Marzioch, A. Bauer, J. Schultz, J. M. Rick, A. M. Michon, C. M. Cruciat, M. Remor, C. Hofert, M. Schelder, M. Brajenovic, H. Ruffner, A. Merino, K. Klein, M. Hudak, D. Dickson, T. Rudi, V. Gnau, A. Bauch, S. Bastuck, B. Huhse, C. Leutwein, M. A. Heurtier, R. R. Copley, A. Edelmann, E. Querfurth, V. Rybin, G. Drewes, M. Raida, T. Bouwmeester, P. Bork, B. Seraphin, B. Kuster, G. Neubauer, and G. Superti-Furga. 2002. Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature 415141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gwizdek, C., N. Iglesias, M. S. Rodriguez, B. Ossareh-Nazari, M. Hobeika, G. Divita, F. Stutz, and C. Dargemont. 2006. Ubiquitin-associated domain of Mex67 synchronizes recruitment of the mRNA export machinery with transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10316376-16381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hieronymus, H., and P. A. Silver. 2003. Genome-wide analysis of RNA-protein interactions illustrates specificity of the mRNA export machinery. Nat. Genet. 33155-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, S., and E. K. O'Shea. 2005. A systematic high-throughput screen of a yeast deletion collection for mutants defective in PHO5 regulation. Genetics 1691859-1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishimi, Y., and A. Kikuchi. 1991. Identification and molecular cloning of yeast homolog of nucleosome assembly protein I which facilitates nucleosome assembly in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2667025-7029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimeno, S., A. G. Rondon, R. Luna, and A. Aguilera. 2002. The yeast THO complex and mRNA export factors link RNA metabolism with transcription and genome instability. EMBO J. 213526-3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kashyap, A. K., D. Schieltz, J. Yates III, and D. R. Kellogg. 2005. Biochemical and genetic characterization of Yra1p in budding yeast. Yeast 2243-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kellogg, D. R., A. Kikuchi, T. Fujii-Nakata, C. W. Turck, and A. W. Murray. 1995. Members of the NAP/SET family of proteins interact specifically with B-type cyclins. J. Cell Biol. 130661-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim, M., S. Ahn, N. J. Krogan, J. F. Greenblatt, and S. Buratowski. 2004. Transitions in RNA polymerase II elongation complexes at the 3′ ends of genes. EMBO J. 23354-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komarnitsky, P., E. J. Cho, and S. Buratowski. 2000. Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev. 142452-2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korber, P., T. Luckenbach, D. Blaschke, and W. Hörz. 2004. Evidence for histone eviction in trans upon induction of the yeast PHO5 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2410965-10974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krogan, N. J., G. Cagney, H. Yu, G. Zhong, X. Guo, A. Ignatchenko, J. Li, S. Pu, N. Datta, A. P. Tikuisis, T. Punna, J. M. Peregrin-Alvarez, M. Shales, X. Zhang, M. Davey, M. D. Robinson, A. Paccanaro, J. E. Bray, A. Sheung, B. Beattie, D. P. Richards, V. Canadien, A. Lalev, F. Mena, P. Wong, A. Starostine, M. M. Canete, J. Vlasblom, S. Wu, C. Orsi, S. R. Collins, S. Chandran, R. Haw, J. J. Rilstone, K. Gandi, N. J. Thompson, G. Musso, P. St Onge, S. Ghanny, M. H. Lam, G. Butland, A. M. Altaf-Ul, S. Kanaya, A. Shilatifard, E. O'Shea, J. S. Weissman, C. J. Ingles, T. R. Hughes, J. Parkinson, M. Gerstein, S. J. Wodak, A. Emili, and J. F. Greenblatt. 2006. Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 440637-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levchenko, V., and V. Jackson. 2004. Histone release during transcription: NAP1 forms a complex with H2A and H2B and facilitates a topologically dependent release of H3 and H4 from the nucleosome. Biochemistry 432359-2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, B., M. Carey, and J. L. Workman. 2007. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 128707-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorch, Y., B. Maier-Davis, and R. D. Kornberg. 2006. Chromatin remodeling by nucleosome disassembly in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1033090-3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luk, E., N. D. Vu, K. Patteson, G. Mizuguchi, W. H. Wu, A. Ranjan, J. Backus, S. Sen, M. Lewis, Y. Bai, and C. Wu. 2007. Chz1, a nuclear chaperone for histone H2AZ. Mol. Cell 25357-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mason, P. B., and K. Struhl. 2005. Distinction and relationship between elongation rate and processivity of RNA polymerase II in vivo. Mol. Cell 17831-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason, P. B., and K. Struhl. 2003. The FACT complex travels with elongating RNA polymerase II and is important for the fidelity of transcriptional initiation in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 238323-8333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizuguchi, G., X. Shen, J. Landry, W. H. Wu, S. Sen, and C. Wu. 2004. ATP-driven exchange of histone H2AZ variant catalyzed by SWR1 chromatin remodeling complex. Science 303343-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosammaparast, N., B. C. Del Rosario, and L. F. Pemberton. 2005. Modulation of histone deposition by the karyopherin Kap114. Mol. Cell. Biol. 251764-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosammaparast, N., C. S. Ewart, and L. F. Pemberton. 2002. A role for nucleosome assembly protein 1 in the nuclear transport of histones H2A and H2B. EMBO J. 216527-6538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mosammaparast, N., K. R. Jackson, Y. Guo, C. J. Brame, J. Shabanowitz, D. F. Hunt, and L. F. Pemberton. 2001. Nuclear import of histone H2A and H2B is mediated by a network of karyopherins. J. Cell Biol. 153251-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neef, D. W., and M. P. Kladde. 2003. Polyphosphate loss promotes SNF/SWI- and Gcn5-dependent mitotic induction of PHO5. Mol. Cell. Biol. 233788-3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park, Y. J., J. V. Chodaparambil, Y. Bao, S. J. McBryant, and K. Luger. 2005. Nucleosome assembly protein 1 exchanges histone H2A-H2B dimers and assists nucleosome sliding. J. Biol. Chem. 2801817-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park, Y. J., and K. Luger. 2006. Structure and function of nucleosome assembly proteins. Biochem. Cell Biol. 84549-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preker, P. J., K. S. Kim, and C. Guthrie. 2002. Expression of the essential mRNA export factor Yra1p is autoregulated by a splicing-dependent mechanism. RNA 8969-980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramey, C. J., S. Howar, M. Adkins, J. Linger, J. Spicer, and J. K. Tyler. 2004. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint in yeast lacking the histone chaperone anti-silencing function 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2410313-10327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinberg, D., and R. J. Sims III. 2006. de FACTo nucleosome dynamics. J. Biol. Chem. 28123297-23301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santisteban, M. S., T. Kalashnikova, and M. M. Smith. 2000. Histone H2A. Z regulates transcription and is partially redundant with nucleosome remodeling complexes. Cell 103411-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saunders, A., L. J. Core, and J. T. Lis. 2006. Breaking barriers to transcription elongation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7557-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schermer, U. J., P. Korber, and W. Horz. 2005. Histones are incorporated in trans during reassembly of the yeast PHO5 promoter. Mol. Cell 19279-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwabish, M. A., and K. Struhl. 2006. Asf1 mediates histone eviction and deposition during elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell 22415-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segref, A., K. Sharma, V. Doye, A. Hellwig, J. Huber, R. Luhrmann, and E. Hurt. 1997. Mex67p, a novel factor for nuclear mRNA export, binds to both poly(A)+ RNA and nuclear pores. EMBO J. 163256-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strasser, K., and E. Hurt. 2001. Splicing factor Sub2p is required for nuclear mRNA export through its interaction with Yra1p. Nature 413648-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strasser, K., and E. Hurt. 2000. Yra1p, a conserved nuclear RNA-binding protein, interacts directly with MEx67p and is required for mRNA export. EMBO J. 19410-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strasser, K., S. Masuda, P. Mason, J. Pfannstiel, M. Oppizzi, S. Rodriguez-Navarro, A. G. Rondon, A. Aguilera, K. Struhl, R. Reed, and E. Hurt. 2002. TREX is a conserved complex coupling transcription with messenger RNA export. Nature 417304-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun, Z. W., and C. D. Allis. 2002. Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast. Nature 418104-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walfridsson, J., O. Khorosjutina, P. Matikainen, C. M. Gustafsson, and K. Ekwall. 2007. A genome-wide role for CHD remodelling factors and Nap1 in nucleosome disassembly. EMBO J. 262868-2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wellinger, R. E., F. Prado, and A. Aguilera. 2006. Replication fork progression is impaired by transcription in hyperrecombinant yeast cells lacking a functional THO complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 263327-3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zenklusen, D., P. Vinciguerra, Y. Strahm, and F. Stutz. 2001. The yeast hnRNP-like proteins Yra1p and Yra2p participate in mRNA export through interaction with Mex67p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 214219-4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zenklusen, D., P. Vinciguerra, J. Wyss, and F. Stutz. 2002. Stable mRNP formation and export require cotranscriptional recruitment of the mRNA export factors Yra1p and Sub2p by Hpr1p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 228241-8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zlatanova, J., C. Seebart, and M. Tomschik. 2007. Nap1: taking a closer look at a juggler protein of extraordinary skills. FASEB J. 211294-1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]