Abstract

Adenoviruses (Ads) with E1B55K mutations can selectively replicate in and destroy cancer cells. However, the mechanism of Ad-selective replication in tumor cells is not well characterized. We have shown previously that expression of several cell cycle-regulating genes is markedly affected by the Ad E1b gene in WI-38 human lung fibroblast cells (X. Rao, et al., Virology 350:418-428, 2006). In the current study, we show that the Ad E1B55K region is required to enhance cyclin E expression and that the failure to induce cyclin E overexpression due to E1B55K mutations prevents viral DNA from undergoing efficient replication in WI-38 cells, especially when the cells are arrested in the G0 phase of the cell cycle by serum starvation. In contrast, cyclin E induction is less dependent on the function encoded in the E1B55K region in A549 and other cancer cells that are permissive for replication of E1B55K-mutated viruses, whether the cells are in the S phase or G0 phase. The small interfering RNA that specifically inhibits cyclin E expression partially decreased viral replication. Our study provides evidence suggesting that E1B55K may be involved in cell cycle regulation that is important for efficient viral DNA replication and that cyclin E overexpression in cancer cells may be associated with the oncolytic replication of E1B55K-mutated viruses.

Adenoviruses (Ads) can infect cells at different cell cycle stages. After infection, viral proteins activate cellular factors and force quiescent G0 cells to enter S or S-like phase for viral DNA synthesis. It is believed that the primary role of the Ad E1A products is to regulate expression of host and viral genes to create a favorable cellular environment for viral replication. Instead of directly binding to specific DNA sequences in transcriptional regulation elements, E1A proteins target key regulators of cell proliferation by interacting with them (12, 17). The well-known cellular factors that E1A proteins bind with are products of the Rb gene and its structural relatives p107 and p130 (49, 88). Sequestration of the protein of Rb (pRB) by E1A frees transcriptional regulator E2F proteins from the pRB/E2F complex. Studies have suggested that the pRB/E2F complex actively represses the transcription from target genes and mediates G1 arrest triggered by p19(ARF)/p53, p16INK4a, TGFb, and contact inhibition (46, 72, 92). The free and active E2F proteins are required to induce cells to enter the S phase by transactivation of cellular promoters containing E2F-responsive elements, including the CDK2 and E-type cyclins (2, 3, 56, 71).

The Ad E1B55K protein performs several functions that are believed to be important for viral replication. E1B55K has been shown in some studies to counteract the E1A-induced stabilization of p53 (14, 64). Several groups have shown that expression of E1A triggers the accumulation of p53 protein and p53-dependent apoptosis (14, 39, 48, 53). E1B55K protein may inhibit the functions of p53 through at least two distinct mechanisms. E1B55K is reported to bind the amino terminus of p53 (40), and this binding may repress p53 transcriptional activation, as suggested in transcription assays (52) and transient transfection studies (91). E1B55K also may interfere with p53 function by cooperating with viral E4-orf6 protein to cause proteolytic degradation of p53 protein (31, 33, 55, 63, 89).

Ad dl1520 (ONYX-015) contains an 827-bp deletion and a point mutation generating a premature stop codon in the E1B55K coding sequence, preventing expression from the gene (4). Since cancer cells defective in the p53 gene or its pathway may not require the E1B55K protein function of inhibiting p53 activity, it was proposed that dl1520 could selectively replicate in these cells (9, 69). This hypothesis has been greatly challenged by several studies showing that a variety of tumor cell lines, regardless of their p53 status, allow efficient replication of dl1520 and other E1b-mutated Ads (13, 15). With E1B55K-mutated Ads unable to interact with p53 (78), studies have shown that the accumulated p53 protein in cells after Ad infection can neither efficiently induce apoptosis nor transcriptionally activate expression of p53-responsive genes (37, 59). The results suggest that Ads may have E1B55K-independent mechanisms to inhibit p53 function and that blocking of p53 activity by E1B55K protein is unlikely to be the major requirement for virus replication. In addition, the E1B55K region also encodes several other products, one of which promotes cell transformation independent of repression of p53 function (81). Therefore, selective replication of dl1520 in cancer cells may be related to the lack of any viral proteins encoded in the E1B55K region. An E1B55K insertion mutant, one specifically impairing the export of viral late mRNAs (25), exhibits defective viral replication in both transformed and normal human cells, suggesting the connection between E1B55K-mediated mRNA export and virus replication (24).

The E1B55K protein also enables the virus to overcome a restriction to its replication imposed by the G0/G1 state of the cell cycle (26). Unlike wt Ad, E1B55K mutants fail to produce progeny efficiently in HeLa cells infected during G0/G1. This restriction has been demonstrated to be independent of p53 status (26, 27) but may relate to functions of the viral E4 orf6 and orf3 proteins (28). E1B55K protein function in the transport of viral mRNA may not be related to the restriction of E1B55K mutant replication in cells infected during G0/G1, because it was reported that the total amount of cytoplasmic late viral mRNA was even greater in cells infected during G0/G1 than in those infected during S phase with either the wt or mutant viruses (28).

We have previously demonstrated that Ads with the wt E1b gene significantly increased expression of several cell cycle-related genes, including cyclin E1, cyclin E2, and CDC25A (66). Cyclin E (E1) is known to have an important role in oncogenic transformation (51, 54). Ectopic overexpression of cyclin E induces S-phase entry and DNA synthesis (73, 86). Studies with cyclin E1−/− E2−/− fibroblast cells have shown that cyclin E controls the DNA replication rate and is critically required for S-phase entry from the G0 state of the cell cycle (22, 60). A recent report has shown that cyclin E also has kinase-independent functions in cell cycle progression by loading minichromosome maintenance complex (MCM) helicases into the DNA replication complex (21). In organotypic cultures of primary human keratinocytes, wt Ad infection triggers high-level accumulation of cyclin E, which is associated with DNA replication (57).

In our current study, we show that the Ad E1B55K gene, or products encoded by the gene, has a function in the induction of cyclin E expression in virus-infected cells and that failure to induce cyclin E overexpression due to the mutations in the E1B55K region prevents viral DNA from undergoing efficient replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Abbreviations.

Ad, adenovirus; wt, wild-type; Ad5, Ad serotype 5; MOI, multiplicity of infection; CPE, cytopathic effect; Rb, retinoblastoma gene; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter; APH, aphidicolin; siRNA, small interfering RNA; Tet, tetracycline; TTA, Tet-off transcription activator; FBS, fetal bovine serum; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine; CDK2, cyclin-dependent kinase 2.

Cells and plasmids.

We used 293 cells (ATCC no. CRL-1573) for Ad amplification. TTA is stably expressed in 293-E2T cells (96). Cell lines used in the experiments included WI-38 (ATCC no. CCL-75), a human diploid cell line derived from normal embryonic lung tissue (35), and A549 (ATCC no. CCL-185), a human lung carcinoma cell line (23). Other cancer cell lines were colorectal carcinoma lines HCT116 (ATCC no. CCL-247), RKO (CRL-2577), and HT29 (HTB-38); hepatoma lines HepG2 (HB-8065) and Hep3B (HB-8064); osteosarcoma cell line Saos2 (HTB-85); and cervical cancer line HeLa (CCL-2) and breast cancer line MDA-MB-231 (HTB-26). All of the cells were cultured in media supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone, Logan, UT), 100 units of penicillin, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, according to ATCC recommendations.

Plasmids pRc/CMV-cycE containing cyclin E cDNA (36) and pGL2-10-4 with the cyclin E promoter region (20) were obtained from Addgene. From these two plasmids, we constructed plasmids pTet-cycE and pCycE-EGFP. In pTet-cycE, the cyclin E cDNA, which was cleaved with EcoRV and EcoRI from plasmid pRc/CMV-cycE, was inserted into the EcoRV-EcoRI site of a plasmid derived from the Tet-off inducible plasmid pUHD10-3 (29, 67). In pCycE-EGFP, the cyclin E promoter (−363 to +87 nucleotides, corresponding to the transcription start site) was cleaved with BamHI and KpnAI from pGL2-10-4 and used to control the EGFP reporter gene from the plasmid pIRES-EGFP (Clontech, Mountain View, CA).

Real-time PCR.

WI-38 cells infected with wt Ad5 and dl1520 were harvested at 12 h and 24 h postinfection. RNA was prepared using the RNeasy mini kit along with RNase-free DNase set to remove any traces of DNA contamination (both kits from Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was prepared from 500 ng of RNA with the TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (ABI/Roche, Branchburg, NJ) based on the manufacturer's instructions. The template cDNAs (12.5 ng/sample) from mock-, Ad5-, or dl1520-infected cells were mixed with SYBR green master mix. Mixtures were aliquoted into 96-well optical reaction plates along with forward and reverse primers for cyclin E (forward, AAGTACACCAGCCACCTCCAGA; reverse, CCCTCCACAGCTTCAAGCTTT) and β-actin (forward, CGATCCACACGGAGTACTTG; reverse, GGATGCAGAAGGAGATCACTG). Primers were designed using ABI primer express software (ABI/Roche, Branchburg, NJ). Each sample was run in duplicate. The ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system was used. Amplicon sizes were all below 200 bp. Data were analyzed using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method. The n-fold change of the target gene from the samples (Ad5 and dl1520 infected) normalized to the housekeeping gene (β-actin) relative to the calibrator (mock infected) is calculated by a 2-ΔΔCT equation: ΔΔCT = ΔCT (sample) − ΔCT (calibrator), where ΔCT is the CT value of the target gene subtracted from the CT value of the housekeeping gene. All were determined in the exponential phase of the reactions (47).

Western blot analysis.

Proteins isolated from WI-38 cells and A549 cells infected with Ad5 or dl1520 or mock infected were harvested at different time points after infection for Western blot analysis. Rabbit anti-cyclin E (M-20) polyclonal antibodies and mouse anti-cyclin A (BF683), cyclin B1 (D-11), and cyclin D1 (DCS-6) (Santa Cruz) were diluted 1:200 to 1:2,000. Mouse monoclonal antibody against human cyclin E (HE12) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was also used to confirm Western blot results. Binding of the primary antibody was detected using a secondary antibody or anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). ECL reagents were used to detect the signals, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL).

Synchronization of cells and virus infection.

Subconfluent cultures of WI-38 and A549 cells were synchronized in the G0 phase by using serum deprivation (serum free or 0.5% FBS). Approximately 4 × 105 cells were plated in a 60-mm plate and maintained in serum starvation medium for 2 or 3 days. Synchronization of cells in the S phase of the cell cycle was achieved by using APH, a reversible inhibitor of eukaryotic DNA polymerase. Cells were treated with 0.1 μg/ml of APH for 24 h and washed in drug-free medium three times before resuspension. Cells were released from the arrest by transferring them to prewarmed medium supplemented with 10% FBS. S-phase synchronization was confirmed by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry after 4 h of APH release. G0-phase and S-phase synchronous cells were mock infected or infected with Ad5 and dl1520 at an MOI of 10. After infection, the cells arrested in the G0 phase were continually maintained in serum-starving medium, while the S-phase cells were cultured in regular medium with 10% FBS. The infected cells were harvested at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h after infection for FACS cell cycle and Western blot analyses.

Viral replication and assessments of CPE.

G0-phase and S-phase synchronous or asynchronous cells were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well and were mock infected or infected with Ad5 or dl1520 at an MOI of 10. The cells were observed daily for CPE. Cells and culture supernatant were harvested at different times after infection. The cell lysate was prepared with three cycles of freezing and thawing. The titer of the Ad was evaluated by standard plaque-forming assay with the 293 cells in six-well plates, as described previously (30, 97).

BrdU incorporation assay.

Synchronous G0-phase A549 and WI-38 cells were prepared as described above. Cells were seeded in eight-well chamber slides with appropriate medium at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well and maintained in serum starvation medium for 48 h. Cells were then infected with Ad5 or dl1520 at an MOI of 10 for 2 h and kept in the serum-starving culture for 2 days. Ad5- and dl1520-infected cells were labeled by 10 mM BrdU for 60 min at 48 h after infection before fixation. Incorporated BrdU was detected by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody. The active sites of DNA replication after Ad infection were determined, according to the method described in a previous publication (87).

Viral DNA assay.

To compare viral DNA within infected cells, A549 and WI-38 cells were divided into 10-cm dishes at 2 × 106 cells/dish. Cells were infected with Ad5 or dl1520 at an MOI of 10 for 2 h. The cells were collected at 0 h, 24 h, and 48 h after infection. Subsequently, total DNA was isolated from the infected cells. After digestion with PstI, DNA samples (5 μg each) were added to 1.0% agarose gel for electrophoresis and transblotted to a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Arlington Heights, IL) for Southern blot analysis with the Ad DNA fragment, as described previously (93).

siRNA transfection and cyclin E-associated kinase assays.

RNA-mediated silencing of the cyclin E gene was performed by using a cyclin E siRNA/siAbTM assay kit (Dharmacon-Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) containing four pooled individual siRNA duplexes specific for targeting the cyclin E antisense strand and using a negative control containing four pooled nonspecific siRNA duplexes. WI-38 cells were transiently transfected with siRNA duplexes by using silMPORER siRNA transfection reagent (Dharmacon-Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) following the manufacturer's instructions. After 36 h, cells were either mock infected or infected with Ad5 at an MOI of 1. The cells were also observed daily for CPE. At the optimal time, gene silencing was monitored by Western blotting (usually 48 h after infection). Cells were lysed in CDK2 lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% Brij 35, 5 mM glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM dithiothreitol), according to the method described in a previous publication (11). Clarified supernatants were immunoprecipitated with anti-cyclin E antibody (Santa Cruz) at 4°C overnight and then 2 h more after adding protein A-Sepharose. Immunocomplexes were washed two times in CDK2 lysis buffer, once in ST buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol), and then once in 1.5× kinase buffer (30 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 15 mM MgCl2, 150 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 1 mM dithiothreitol). Pellets were resuspended in 20 μl of 1.5× kinase buffer, and kinase reactions were initiated by the addition of 10 μl of CDK2 kinase mixture containing 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham), 50 μM of ATP, and 4 μg of histone HI (Sigma). Reactions were performed at 37°C for 30 min and stopped by the addition of 6 μl of 5× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer. Reactions were fractionated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels followed by autoradiography to assess histone phosphorylation. Gels were scanned with a Typhoon 9400 laser scanner (Amersham Biosciences, Sunnyvale, CA). Phosphorylated proteins were analyzed with Image Quant software (v. 5.2; Amersham Biosciences, Sunnyvale, CA).

RESULTS

The Ad E1B55K region is required to enhance cyclin E overexpression.

We have previously observed that the Ad E1b gene products alter expression of various cellular genes in Ad-infected cells (66). After WI-38 human lung fibroblast cells were infected with wt Ad5 or Adhz60 (the latter lacks the entire E1b gene) (65), the cDNA microarray study showed that the E1b gene affected the expression of a diverse range of genes, including those involved in the cell cycle, apoptosis, stress responses, and angiogenesis (66). Among the genes important in cell cycle progression, expression levels of cyclin E1, cyclin E2, and CDC25A all were increased about threefold. The results suggest that Ad E1B products may be involved in manipulation of the host cell cycle.

We are especially interested in cyclin E expression affected by E1B because cyclin E has an important role in DNA replication and cell cycle progression (22, 60). Since the E1b gene encodes the two major proteins, E1B19K and E1B55K, we wished to determine whether one or both of the E1B proteins (or regions) are required for induction of cyclin E expression in virus-infected cells. We evaluated the cyclin E mRNA levels in WI-38 cells after infection with Ad5, Adhz60, or dl1520, each at an MOI of 10. At 12 h and 24 h after infection, RNAs were isolated from cells and converted to cDNA for quantitative real-time PCR using the primers that were indicated in Materials and Methods to determine cyclin E (E1) mRNA level changes. The results showed that infection with Ad5 resulted in a fourfold increase of cyclin E mRNA levels at 12 h postinfection compared to the level for mock infection (Fig. 1A). In contrast, cells infected with either dl1520 or Adhz60 could not induce cyclin E expression at 12 h. Ad5 infection further led to a 10-fold increase of cyclin E mRNA levels at 24 h, whereas dl1520 and Adhz60 only triggered a three- to fourfold increase at the same time point. dl1520 and Adhz60, with a partial or entire deletion of the E1b gene, can still increase cyclin E expression, consistent with the previous observation that expression of E1A increased cyclin E gene expression (19, 83). However, the expression of cyclin E induced by Ad5 (with the E1b gene) is consistently about threefold greater than that induced by dl1520 or Adhz60 at both 12 h and 24 h (Fig. 1A). The difference in cyclin E mRNA levels between the cells affected by dl1520 and Adhz60 was not significant. These results indicate that the deletion of the E1B55K region affects cyclin E gene transcription.

FIG. 1.

(A) Comparison of cyclin E mRNA levels in WI-38 cells infected with Ad5, dl1520, or Adhz60 using quantitative real-time PCR. The reaction was performed in duplicate for both the target gene and β-actin normalizer. The level of gene expression was calculated after normalizing against β-actin. The values indicate the n-fold change of cyclin E in cells at 12 h and 24 h postinfection at an MOI of 10 compared with the change in mock infection. The values are means ± standard errors of the means from two independent determinations (P of <0.01 by Student's t test). (B) Western blot analysis of cyclin E (cyc E) produced in WI-38 cells 2 days after mock infection or infection with Ad5, Adhz60, or dl1520 at an MOI of 10. Antibodies against cyclin E and β-actin were used. *, P < 0.01, Student's t test.

We further evaluated the cyclin E protein levels produced in WI-38 cells after infection with Ad5, Adhz60, or dl1520 at an MOI of 10. The cyclin E protein level significantly increased in WI-38 cells after Ad5 infection by 48 h (Fig. 1B). At this time point, the cyclin E protein was barely detected in WI-38 cells infected with dl1520 or Adhz60. The result is consistent with the quantitative real-time PCR result (Fig. 1A) and our previous cDNA microarray study (66). The products encoded in the E1B55K region in Ad5, lacking in both Adhz60 and dl1520, may be responsible for the increased cyclin E expression in WI-38 cells.

The E1B55K region is less important for induction of cyclin E protein in A549 cancer cells.

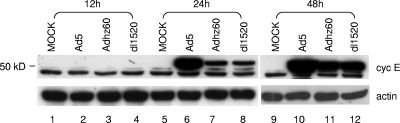

The role of cyclin E in tumorigenesis has recently been investigated (51, 54). Previously, we showed that viruses with partial or entire deletions of E1b are able to replicate in A549 human lung cancer cells (65). If oncolytic replication of E1b-mutated Ads is dependent on cyclin E overexpression in cancer cells, then A549 cells either may constitutively produce cyclin E or can be induced to overexpress cyclin E by the E1B-mutated viruses. To verify this, A549 cells were mock infected or infected with Ad5, dl1520, or Adhz60 and assessed by Western blotting, as described above for WI-38 cells. A small cyclin E isoform protein was clearly observed in samples from mock-infected cells. A larger cyclin E protein was strongly induced in A549 cells by Ad5 infection at 24 h and 48 h (Fig. 2, lanes 6 and 10). The production of the two forms of cyclin E protein may be caused by the use of different ATG start codes (58); this will be discussed later. Interestingly, dl1520 and Adhz60 also induced cyclin E production in A549 cells, although the levels were relatively lower than in Ad5-infected A549 cells (Fig. 2, lanes 7, 8, 11, and 12). We conclude that A549 cancer cells are less dependent on E1B55K for the induction of cyclin E expression.

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis of cyclin E (cyc E) produced in A549 cells after mock infection or infection with Ad5, Adhz60, or dl1520 at an MOI of 10. Cells were collected at the indicated times postinfection and subjected to Western blot analysis, as described in Materials and Methods. β-Actin was used as a control to demonstrate an equal loading and transfer.

E1A overexpression cannot completely compensate for the lack of E1B55K function in cyclin E induction.

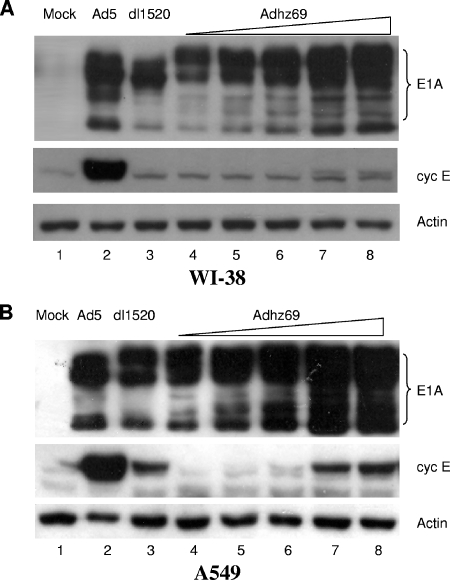

We have previously shown that E1B55K can increase E1A expression in virus-infected cells (95). It is well known that viral E1A displaces E2F transcription factors from the Rb pocket proteins, resulting in activation of E2F target genes (18, 54, 79, 80). A previous report has shown that E1A induced cyclin E expression (19). Thus, it is unclear whether E1B55K is a genuine activator of cyclin E expression or if the elevated level of cyclin E is primarily a consequence of higher E1A expression from Ad5. We used Adhz69 (94), a mutant with a deletion in the E1B55K gene, to determine the effect of E1A overexpression on cyclin E expression in virus-infected cells in the absence of E1B55K. The strong cytomegalovirus promoter was used to replace the E1a endogenous promoter in Adhz69, resulting in constant overexpression of the E1A proteins in infected cells (94, 95). We infected WI-38 and A549 cells with increasing levels of Adhz69 (MOIs of 0.25, 0.64, 1.6, 4, and 10). Separately, the cells were also infected with Ad5 or dl1520 at an MOI of 10. As expected, the increased Adhz69 resulted in increased levels of E1A products in both WI-38 and A549 cells compared with levels in cells infected with Ad5 or dl1520 (Fig. 3). E1A overexpression increased cyclin E expression about twofold in Adhz69-infected cells compared with levels in dl1520-infected cells (Fig. 3A and B, lanes 3 versus 8). However, cyclin E protein levels mediated by Adhz69 were still about 10-fold lower than those in Ad5-infected cells in at least three repeated experiments (Fig. 3A and B, lanes 2 versus 4 to 8). Therefore, E1A overexpression cannot entirely compensate for the E1B55K function in cyclin E induction.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of adenoviral E1A and cyclin E proteins produced in WI-38 (A) and A549 (B) cells after mock infection or infection with Ad5 or dl1520 at an MOI of 10 or with increasing amounts of Adhz69 (MOIs of 0.25, 0.64, 1.6, 4, and 10). Cells were collected at day 2 postinfection and subjected to Western blot analysis.

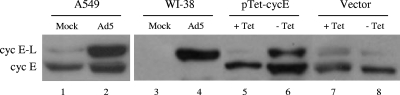

Ad5 increases cyclin E-L expression in A549 and WI-38 cells.

To confirm the cyclin E protein induced by Ad infection, we constructed a plasmid pTet-cycE, in which the cyclin E cDNA is under the control of the Tet-off inducible promoter (29, 67). Thus, the cyclin E expression from pTet-cycE can be induced by TTA in the absence of Tet. We introduced the pTet-cycE plasmid DNA into 293-E2T cells to determine cyclin E expression; 293-E2T cells can stably express the TTA protein and be efficiently transfected with plasmid DNA (96). Two days after transfection, proteins were isolated for Western blotting with the cyclin E antibody. Tet did not affect endogenous cyclin E expression in mock-transfected 293-E2F cells (Fig. 4, lanes 7 and 8). Removing Tet increased the small and large forms of cyclin E in 293-E2T cells transfected with pTet-cycE (Fig. 4, compare lanes 5 and 6). The two forms of cyclin E protein were identical to the ones observed with the Ad5-infected A549 cells; the large cyclin E (cyclin E-L) protein band was the primary form induced in Ad5-infected WI-38 cells (Fig. 4, lanes 1 to 4). Two alternatively spliced forms of cyclin E mRNA were detected in human cells (58). Translation of the cyclin E-L was reported to be initiated at an ATG codon located in exon 2. Cyclin E-L has an N terminus that is 15 amino acids longer than that of cyclin E, the small isoform, which initiates in frame from an ATG codon in exon 3. A549 cells constitutively produce the cyclin E protein. Ad5 infection appears to induce primarily the cyclin E-L in both A549 and WI-38 cells. The cyclin E cDNA in pTet-cycE contains exons 2 and 3, including the two translation start codons that are separated by the 15-amino-acid coding sequences. It is likely that both start codons can be used, resulting in the induction of the cyclin E-L and cyclin E in 293-E2T cells after pTet-cycE transfection. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies showing both cyclin E-L and cyclin E were produced when a similar plasmid with the identical cyclin E cDNA was used (34). Our results suggest that Ad5 infection primarily increases cyclin E-L expression.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis to confirm cyclin E (cyc E) protein induced by Ad infection. The pTet-cycE plasmid was introduced into 293-E2T cells to induce cyclin E expression by the Tet-off expression system. The cyclin E proteins induced by Ad5 infection are identical to the ones produced from the pTet-cycE plasmid when Tet was removed.

We further studied whether the cyclin E promoter activity may be affected by virus infection in cancer and normal cells. We constructed another plasmid pCycE-EGFP, in which the cyclin E promoter region (−363 to +87) was applied to control the reporter gene EGFP. We introduced pCycE-EGFP into both WI-38 cells and A549 cancer cells and then infected these cells with Ad5 or dl1520. Two days later, EGFP activity in WI-38 and A549 cells was evaluated (Fig. 5A). Without infection, EGFP expression driven by the cyclin E promoter was higher in A549 cells than in WI-38 cells, suggesting that the cyclin E promoter is more active in cancer cells than in normal cells. Ad5 infection significantly increased EGFP expression in both WI-38 and A549 cells. In contrast, the dl1520 could not increase EGFP expression as strongly as Ad5, especially in WI-38 cells. These results suggest that E1B55K may enhance cyclin E expression via activation of the transcription from the 450-bp cyclin E promoter (−363 to +87).

FIG. 5.

(A) The plasmid pCycE-EGFP was transfected into WI-38 and A549 cells, which were then mock infected or infected with Ad5 or dl1520. EGFP expression under the control of the cyclin E promoter was determined 2 days later. Ad5 infection activated the cyclin E promoter and resulted in higher EGFP expression. (B) Cell cycle profiles of A549 and WI-38 cells after incubation in 0.5% serum medium for 2 days. Cells were stained with propidium iodide for FACS analysis. (C) BrdU incorporation into serum-starved quiescent Ad-infected A549 and WI-38 cells. Ad5- and dl1520-infected cells were labeled by 10 mM BrdU for 60 min before fixation at 48 h postinfection. Incorporated BrdU was detected by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody. Hoechst staining was used to identify nucleus localization. Cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline and analyzed using a fluorescent microscope (Olympus X-70). (D) Southern blotting was used to determine the viral DNA synthesis within A549 and WI-38 cells infected at synchronous G0 versus S phase. The DNA was isolated from the cells at days 0, 1, and 2 postinfection and fragmented with the restriction enzyme PstI. The probe was Ad5 genome DNA.

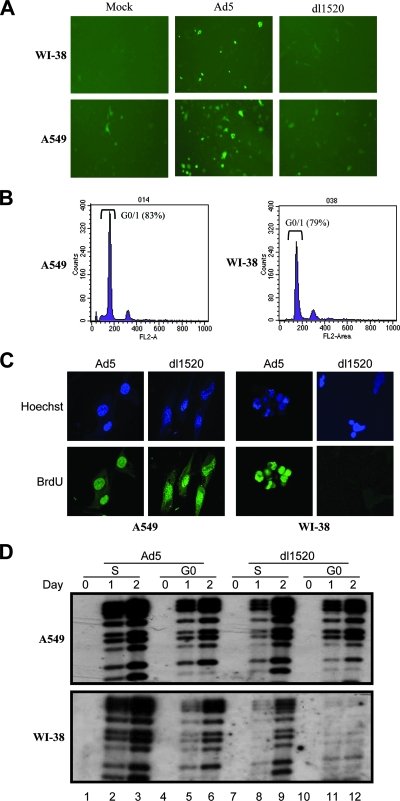

dl1520 viral DNA synthesis is more restricted in serum-starved normal cells.

In normal cells, cyclin E expression occurs during a brief window of time from late G1 into early S phase with a peak expression level near the restriction “R” point (44). Cyclin E is essential for cells to reenter the cell cycle from the G0 state (22, 60). Given that E1B55K has a function to induce cyclin E expression, it may be required for forcing G0 cells to enter an S-like phase for efficient virus DNA replication. To study E1B55K function associated with cyclin E induction, we analyzed viral DNA synthesis in A549 and WI-38 cells arrested in the G0 state. A549 and WI-38 cells were cultured in serum-starving media for 2 days, resulting in about 80% of A549 and WI-38 cells being arrested in their G0 phase (Fig. 5B). These cells were then infected with Ad5 or dl1520 at an MOI of 10. After virus infection, cells remained continually in the serum-starving cultures for the entire experiment. We compared DNA syntheses in A549 and WI-38 cells after infection with Ad5 or dl1520. A549 and WI-38 cells were labeled by 10 mM BrdU for 60 min at 48 h after infection. BrdU was incorporated into the DNA of A549 cells infected with Ad5 (98% of cells) or dl1520 (92% of cells) (Fig. 5C). The strong BrdU-positive cells (95%) were also detected among WI-38 cells infected with wt Ad5 but not among cells infected with dl1520 (Fig. 5C). Only weak labeling could be observed with a few G0-arrested WI-38 cells after infection with dl1520, indicating repressed DNA synthesis. For each of the above treatments, 100 or more cells were examined. To verify DNA synthesis, Southern blot analysis was applied to determine viral DNA changes in A549 and WI-38 cells (Fig. 5D). If the function of E1B55K is required for driving G0-arrested WI-38 cells to reenter an S-like phase, then WI-38 cells infected during S phase may be less dependent on the function of E1B55K for dl1520 replication. Synchronization of A549 and WI-38 cells in the S phase of the cell cycle was achieved by using APH, a reversible inhibitor of eukaryotic DNA polymerase. Cells were released from the arrest by culturing in a drug-free medium supplemented with 10% FBS. At 4 h after APH removal, A549 and WI-38 cells entered S phase and were mock infected or infected with Ad5 or dl1520. The G0-arrested A549 and WI-38 cells remained in serum-starving medium before and after infection. Total DNA was isolated from cells at day 0, 1, and 2 postinfection. The DNA was digested with PstI and then subjected to Southern blotting with an Ad DNA fragment. The dl1520 DNA was amplified in A549 cells infected during S and G0 phases and also in S-phase WI-38 cells, but dl1520 DNA replication was strongly inhibited in G0-arrested WI-38 cells (Fig. 5D). The control Ad5 increased in A549 and WI-38 cells infected in both S and G0 phases. Our results suggest that E1B55K may be involved in viral DNA synthesis by inducing cyclin E expression to overcome the G0-state restriction.

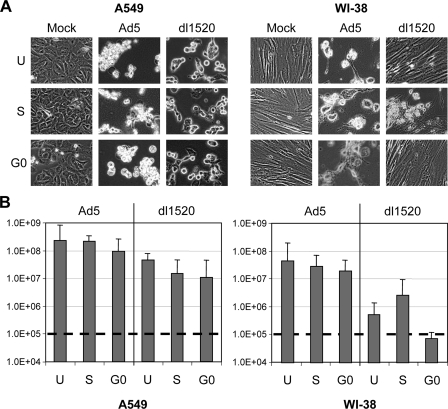

Replication of E1B55K-mutated virus is less restricted in S-phase cells.

We further investigated the replication of Ad5 and dl1520 in A549 and WI-38 cells in S, G0, or unsynchronized states. S and G0 cells were treated as described above. Figure 6A, representing one of three repeat experiments, shows the results of CPE analysis of A549 and WI-38 cells at 3 days postinfection with Ad5 or dl1520. Nearly 100% of the A549 cells showed CPE after infection with Ad5, regardless of having been infected in an S, G0, or unsynchronized state. This was also true for A549 cells infected by dl1520 (Fig. 6A). We also observed that most of the WI-38 cells in S phase or G0 phase infected by Ad5 displayed CPE (Fig. 6A). In contrast, dl1520 caused partial CPE in WI-38 cells infected in S phase, but no clear CPE was observed with WI-38 cells infected by dl1520 during G0 phase. It appears that the differences in the CPE were related to the phase of the WI-38 cell cycle and the E1B55K function. We then compared the titers of Ad5 and dl1520 that were produced in A549 and WI-38 cells at day 3 after infection (Fig. 6B). Ad5 could efficiently replicate in both cancer and normal cells in G0 and S phases. Although dl1520 replication is not as efficient as Ad5 in A549 cancer cells, dl1520 titers increased more than 100-fold, from 105 input level to 107 per ml, regardless of whether the cells were infected in S phase or G0 state. As expected, dl1520 replication was strongly inhibited in G0-arrested WI-38 cells. The restriction for dl1520 replication in WI-38 normal cells was partially released in the S phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

(A) Comparison of CPE in A549 and WI-38 cells infected with Ad5 and dl1520 at G0 or S phases. All microscopy is originally at a magnification of ×20 at 72 h postinfection. (B) Comparison of Ad5 and dl1520 replication in A549 and WI-38 cells. The dashed line indicates the level of virus added into the cell culture originally. The bars represent the means ± standard errors of the means obtained from triplicate determinations at 72 h postinfection. U, unsynchronized; S, S phase; G0, G0 phase.

Virus replication correlated with cyclin E expression.

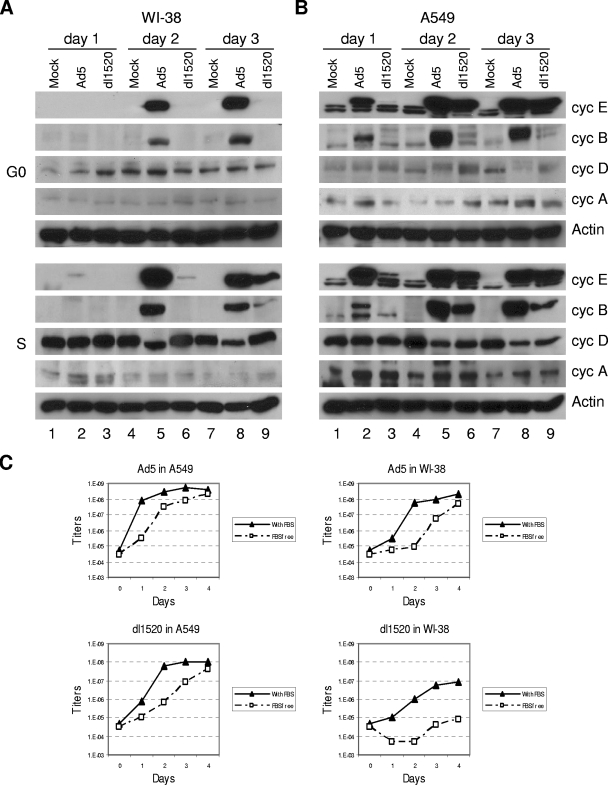

We isolated total cellular proteins from A549 and WI-38 cells infected with Ad5 or dl1520 to evaluate expression of various cyclins. To completely arrest cells in G0 phase for this experiment, cells were cultured in totally serum-free medium for 3 days before infection and remained in the serum-free culture after infection. Cells were infected with Ad5 or dl1520 at an MOI of 10. In synchronously S-phase and serum-starved G0 WI-38 cells, Ad5 infection increased cyclin E expression at day 2 and day 3 postinfection (Fig. 7A, lanes 5 and 8). Cyclin E expression was barely detected in the dl1520-infected WI-38 cells arrested in G0, whereas an increase of cyclin E expression was found in S-phase WI-38 cells at days 2 and 3 after infection with dl1520 (Fig. 7A, lanes 6 and 9), consistent with the delayed and lower cyclin E mRNA induction in dl1520-infected WI-38 cells (Fig. 1A). Both Ad5 and dl1520 could induce cyclin E expression in A549 cells in G0 or S phases (Fig. 7B). Again, the results suggest that E1B55K function is critically required for cyclin E induction in serum-starved WI-38 cells. We also evaluated productions of other cyclin proteins. Ad5 infection induced cyclin B in A549 and WI-38 cells (Fig. 7A and B). The induction of cyclin B may be enhanced by E1B55K because the lack of E1B55K in dl1520 resulted in less induction of cyclin B in both cells (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 6 and 9). In contrast to the clear effects on the induction of cyclin E and B proteins, only modest changes in the levels of cyclin A and D were observed in A549 and WI-38 cells after infection with Ad5 or dl1520. Cyclin B normally begins to accumulate in late S phase and forms an inactive complex with CDC2 kinase. It has been reported that the stable association of cyclin B/CDC2 to chromosome replication origins inhibits cellular DNA replication (90). Thus, it is possible that the induced cyclin E expression may increase viral DNA amplification and, at the same time, cyclin B expression may block host cellular DNA replication.

FIG. 7.

Western blot analysis of cyclin E (cyc E) and cyclins B, D, and A produced in (A) WI-38 and (B) A549 cells mock infected or infected with Ad5 or dl1520 during G0 or S phase. Cells were collected at days 1, 2, and 3 postinfection and subjected to Western blot analysis. β-Actin was used as a control to demonstrate an equal loading and transfer. (C) Viral growth kinetics in A549 and WI-38 cells cultured in 10% serum or serum-free medium. The virus titers produced in the cultures were determined at days 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4.

To correlate viral growth kinetics with expression of cyclin E in S-phase and G0-arrested cells, we determined virus titers produced in A549 and WI-38 cells from day 0 (4 h) to day 4 after infection (Fig. 7C). The Ad5 replication in serum-free A549 and WI-38 cells was delayed 1 or 2 days compared to cells growing with 10% serum medium. The dl1520 replication was also delayed in serum-free A549 cells. However, the final titers of Ad5 in A549 and WI-38 cells with or without serum were similar at day 4. This was also true for dl1520 in A549 cells. In contrast, the dl1520 replication was significantly inhibited in serum-free WI-38 cells. The titer of dl1520 was decreased for 2 days and then slightly increased until day 4. The final titer of dl1520 was 100-fold lower in serum-free WI-38 cells than in the same cells cultured with normal serum. These studies further demonstrated that virus replication is affected by cyclin E expression in Ad-infected cells.

Specific siRNA represses cyclin E activity and partially inhibits virus replication.

If cyclin E overexpression induced by viral infection is critical in the virus life cycle, we expect that blocking cyclin E expression may inhibit viral replication. siRNA, a short double-strand of RNA (19 to 23 bases in length), can sequence-specifically cleave up to 95% of the target mRNA in the cell (7, 85). A siRNA/siAbTM assay kit (Dharmacon-Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) that contains four pooled individual siRNA duplexes targeting cyclin E mRNA was applied to specifically inhibit cyclin E production. The negative control was a pool of nonspecific siRNA duplexes. Since cyclin E in WI-38 cells can be significantly induced by Ad5, we investigated the effect of the siRNA with Ad5-infected WI-38 cells. In this experiment, WI-38 cells were first transiently transfected with siRNA duplexes. After 36 h, WI-38 cells were then either mock infected or infected with Ad5 at an MOI of 1. At 48 h postinfection, gene silencing was monitored by Western blotting. Western blot analysis revealed that the cyclin E-specific siRNA inhibited expression of cyclin E by 90%, compared with the levels in cells transfected with the control nonspecific siRNA (Fig. 8A, lanes 2 and 4) and with the cyclin E protein standard of twofold serial dilution (lower part of Fig. 8A). We also examined the cyclin E-associated kinase activity. Anti-cyclin E immunoprecipitates were prepared, followed by in vitro kinase assays using histone HI as substrate in the presence of 32P-labeled ATP (11). Ad5 infection strongly upregulated the cyclin E-dependent kinase activity in cells treated with the control nonspecific siRNA (Fig. 8B, compare lanes 3 and 4). However, a partial decrease of cyclin E-associated kinase activation was observed in response to cyclin E siRNA transfection (Fig. 8B, compare lanes 2 and 4). The cyclin E kinase activity was consistent with the cyclin E protein level. Blockage of cyclin E expression with siRNA notably delayed CPE in Ad5-infected WI-38 cells, but it could not completely prohibit CPE (Fig. 8C). Furthermore, we observed that repressed cyclin E expression by siRNA led to a decrease of virus replication; the specific siRNA decreased the viral titer about threefold in the above experimental conditions, from an average of 7.7 × 106 to 2.5 × 106 in three repeated experiments (Fig. 8C). Thus, repressed cyclin E expression with siRNA decreased cyclin E expression and its associated kinase activity, and it partially inhibited the virus replication.

FIG. 8.

(A) At 36 h after transfection with the cyclin E (cycE)-specific or nonspecific siRNA, WI-38 cells were mock infected or infected with Ad5. Cyclin E protein levels in WI-38 cells were determined at 48 h postinfection with anti-cyclin E antibodies. Ad5-induced cyclin E is significantly inhibited by the cyclin E-specific siRNA. The cyclin E protein level standard is a twofold dilution series of Ad5-infected WI-38 cell lysates. (B) Cyclin E-associated kinase activity was determined by in vitro kinase assays using histone HI as substrate in the presence of 32P-labeled ATP. (C) Comparison of CPE and virus production in WI-38 cells treated with siRNA-cyclin E or nonspecific siRNA. The cyclin E-specific siRNA partially repressed CPE and led to a threefold decrease of viral titers in WI-38 cells.

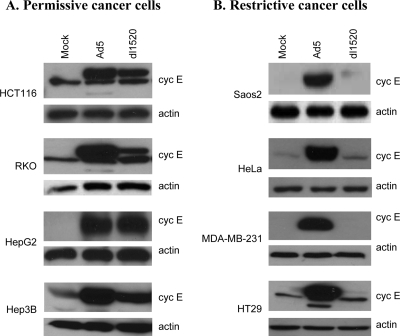

Cyclin E overexpression is correlated with virus replication in cancer cells.

The above results suggest that E1B55K is involved in enhancing cyclin E expression. The function of E1B55K appears to be required for virus replication, especially after infecting G0-arrested normal cells. However, the Ad E1B55K gene is less important in A549 cancer cells. According to previous studies, many cancer cells can support replication of E1B55K-mutated viruses, but other cancer cells are resistant to the replication. We suspect that the “permissive” cancer cells, which are able to support E1B55K-mutated virus replication, may be induced to express high levels of cyclin E after dl1520 infection, while the “restrictive” cancer cells may not be induced to express cyclin E. To correlate cyclin E expression and dl1520 oncolytic replication, four permissive cancer cell types (HCT116, RKO, HepG2, and Hep3B) and four restrictive cancer cell types (Saos2, HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and HT29) were infected with Ad5 or dl1520. Published reports have shown that after infection of the permissive cancer cells, dl1520 yields are either similar to (HCT116) (59) or only three- to fourfold lower (RKO and HepG2 [32, 59] and Hep3B [95]) than Ad5 yields. Studies also have shown that dl1520 replication is significantly repressed in all of the four restrictive cell types; the ratio of dl1520/Ad5 is only 1% in Saos2 (95) or 2 to 3% in HeLa (32) and MDA-MB-231 and HT29 (59) cells. We determined cyclin E protein levels in these virus-infected cells using Western blot analysis at day 3 after infection. Infection with dl1520 can efficiently induce cyclin E expression in all of the four permissive cancer cell types, HCT116, RKO, HepG2, and Hep3B, although it was less effective than wt Ad5 in HCT116 and RKO cells (Fig. 9A). Ad5 infection could also induce high levels of cyclin E expression in the restrictive cancer cell types Saos2, HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and HT29; however, the cyclin E expression was largely not induced in the restrictive cancer cells after dl1520 infection (Fig. 9B). Thus, Ad5 can induce cyclin E expression in all permissive and nonpermissive cancer cells, whereas dl1520 can only increase cyclin E expression in permissive cancer cells. It is likely that induction of cyclin E expression by dl1520 is correlated with selective replication of the virus in cancer cells.

FIG. 9.

Western blot analysis of cyclin E (cyc E) protein produced in (A) permissive cancer cells (HCT116, RKO, HepG2, and Hep3B) and (B) restrictive cancer cells (Saos2, HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and HT29) infected with Ad5 or dl1520. Ad5 infection significantly increased cyclin E protein levels in both permissive and restrictive cancer cells. dl1520 infection could only induce cyclin E expression in the four permissive cancer cell types but not in any of the restrictive cancer cell types.

DISCUSSION

Tumor-selective replication of E1b-mutated Ads is being evaluated clinically as a novel approach in cancer gene therapy (8, 10, 42, 68). Understanding the function of E1B55K in virus and host-cell interaction will enable us to improve the efficacy and safety of the virus-mediated oncolytic therapy. In the current report, we have demonstrated that the Ad E1B55K region is involved in the induction of cyclin E expression, that the function of cyclin E induction encoded in the E1b region is not critically required for virus replication in permissive cancer cells, and that failure to increase cyclin E expression prevents E1B55K-mutated viruses from undergoing effective replication.

It is well known that viral E1A plays an important role in cell cycle alteration (6). Previous studies have shown that the inactivation of pRB family proteins and CDK inhibitor p21, through the binding of the E1A proteins, leads to the induction of cyclin E-CDK2 activity (50, 61). Consistent with this, we observed that viruses (dl1520 and Adhz60) expressing wt E1A without E1B55K could still increase cyclin E mRNA in the range of three- to fourfold in WI-38 cells in the late infection stage at 24 h (Fig. 1). However, infection with wt Ad5 expressing E1A and E1B55K increased cyclin E transcription over 10-fold at the same time point (Fig. 1). In addition, E1A overexpression cannot completely compensate for the cyclin E induction function encoded in the E1B55K region (Fig. 3).

Constructed from dl309, dl1520 also lacks E3 sequences and carries a mutation just upstream of the start of the VA1 gene. Since Adhz60 and Adhz69 are constructed based on Ad5, they do not carry the other mutations found in dl1520. The lack of cyclin E induction associated with dl1520, Adhz60, and Adhz69 should be related to the E1B55K region commonly deleted or mutated in those viruses. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that cyclin E induction may be affected by other products encoded in the E1B55K region. Although the E1B19K and E1B55K proteins are the major products encoded in the E1b gene, the 55K region also encodes at least three other polypeptides generated by alternative splicing of a common mRNA precursor (81, 84). A recent study has shown that the E1B 156R protein encoded in the E1B55K region has an important function in cell transformation (81). For the same reason, the selective replication of dl1520 in cancer cells may not be related exclusively to the E1B55K protein.

According to studies with a cyclin E1 and E2 double knockout, E-type cyclins have two essential functions: driving the G0 state into the S phase of the cell cycle and increasing the DNA replication rate (22, 60). Both functions are critical for virus DNA replication. Given the ability to induce cyclin E expression, the E1B55K region may be required for virus replication after infection of quiescent G0 cells. dl1520 failed to increase cyclin E expression and also could not undergo effective replication after infection of the G0-arrested WI-38 cells (Fig. 5 and 6). These restrictions were partially relieved when WI-38 cells were infected during S phase. In contrast, Ad5 could replicate in WI-38 cells in S and G0 states. The cyclin E induction and Ad DNA replication are less dependent on the E1B55K region in A549 cancer cells (Fig. 6 and 7). Thus, E1B55K protein (or other polypeptides encoded in this region) may have a specific function in the induction of cyclin E expression, and this function could be critically required for virus replication after infection in quiescent or G0-arrested normal cells.

The E1B55K-enhanced cyclin E induction may correlate with the clinical observation that dl1520 selectively replicates in and destroys tumor cells at the exclusion of surrounding normal tissue (42). Loss of normal cell cycle control is a hallmark of tumorigenesis. Molecular analysis of human tumors has shown that cyclin E is frequently overexpressed in many human tumors, including breast and lung cancers (16, 38, 51, 54, 82). In addition, cyclin E overexpression is correlated with tumor progression and predicts a poor prognosis in cancer patients (5, 41, 45). Thus, the abnormal regulation of cyclin E or its potent inhibitors (such as p21Cips and p27Kips) may contribute to cell cycle dysregulation and allow dl1520-selective replication in cancer cells. We have extended our study into several cancer cell types. We observed that the wt virus can replicate and also induce cyclin E expression in all tested cancer cells (Fig. 9). However, dl1520 can increase cyclin E expression in the permissive cancer cells that support dl1520 replication but cannot induce cyclin E expression in the restrictive cancer cells that are resistant dl1520 replication. These data suggest that cyclin E overexpression is correlated with dl1520 oncolytic replication.

E1B55K-enhanced cyclin E induction appears to be unrelated to the cellular p53 status. Among the permissive cancer cell types, HCT116, RKO, and HepG2 are p53 wt and Hep3B is p53 null. In the restrictive cancer cells, Saos2 and HeLa are p53 wt and MDA-MB-231 and HT29 are p53 mutants (27, 32, 70). It is also unlikely that the repressed cyclin E expression and restrictive dl1520 replication in the restrictive cancer cells are caused by poor Ad infection. Although Ad infection efficiency can be different from cell line to cell line, dl1520 and Ad5, having the same viral particles, should equally infect a given type of cell. In addition, our previous report has shown that the permissive Hep3B and restrictive Saos2 cells were equally infected by Ad vectors (95). We also demonstrated that cancer A549 and normal WI-38 cells were also equally infected by Ads (94).

There are several lines of studies suggesting that Ad E1B55K has a novel function related to cell cycle regulation that may be independent of its p53 inactivation. First, E1B55K-mutated viruses are highly impaired in their ability to produce viruses in HeLa cells (1, 62), which contain and express the human papillomavirus E6 protein (43, 76, 77). The E6 protein, having a function of interfering with p53 (74, 75), cannot compensate for E1B55K loss for virus replication in HeLa cells. Second, replication of E1B55K-mutated viruses in HeLa cells is less restricted in S phase than in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle, and this cell cycle restriction on viral replication was reportedly independent of p53 functions (26, 27). Third, our recent work with cDNA microarray analysis has demonstrated that various genes involved in the cell cycle were increased by E1B proteins (66). Finally, we now show that E1B55K is involved in the induction of cyclin E overexpression that is needed for virus-efficient replication, especially in quiescent cells. The obvious advantage of upregulating cyclin E expression by virus infection would be to force cells to enter into an S or S-like phase, in which the cell would express proteins and substrates that could be required for virus replication.

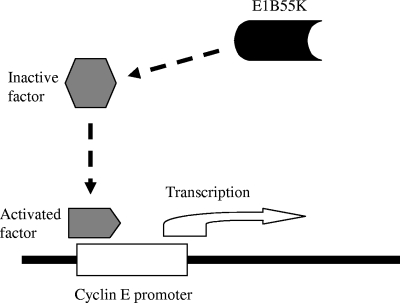

The results presented in this study suggest that E1B55K or products encoded in this region probably activate cellular factors to target the cyclin E promoter region (−363 to +87) for induction of cyclin E transcription (Fig. 10). Such cellular factors may be already activated or partially activated in permissive cancer cells; thus, these cancer cells are less dependent on the E1B55K function for cyclin E induction and viral DNA replication. Our studies suggest that E1B55K-enhanced cyclin E overexpression may be involved in cell cycle manipulation and may be associated with selective replication of E1B55K-mutated viruses in cancer cells. Identifying the factors that are targeted by E1B55K may help to reveal the mechanism of cyclin E overexpression and its functions in tumorigenesis.

FIG. 10.

E1B55K may activate cell factors which, in turn, target the cyclin E promoter to increase expression. The cell factors may already be activated in cancer cells; thus, cancer cells are less dependent on the E1B55K function for cyclin E induction and viral DNA replication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Donald Miller and Douglas Dean at the James Graham Brown Cancer Center and Piotr Sicinski at Harvard Medical School for their help and discussions. We also thank Margaret Abby and Andrew Marsh for editing.

This work was supported by NIH R01 grant CA90784-01A1 (K.M.M.), research grant G030983 from the Kentucky Lung Cancer Research Program, and a pilot grant from the James Graham Brown Cancer Center at the University of Louisville (H.S.Z.). X.Z. is partially supported by the Nature Science Fund of China (30371625).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 January 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Babiss, L. E., and H. S. Ginsberg. 1984. Adenovirus type 5 early region 1b gene product is required for efficient shutoff of host protein synthesis. J. Virol. 50202-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagchi, S., P. Raychaudhuri, and J. R. Nevins. 1990. Adenovirus E1A proteins can dissociate heteromeric complexes involving the E2F transcription factor: a novel mechanism for E1A trans-activation. Cell 62659-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandara, L. R., and N. B. La Thangue. 1991. Adenovirus E1a prevents the retinoblastoma gene product from complexing with a cellular transcription factor. Nature 351494-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker, D. D., and A. J. Berk. 1987. Adenovirus proteins from both E1B reading frames are required for transformation of rodent cells by viral infection and DNA transfection. Virology 156107-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berglund, P., and G. Landberg. 2006. Cyclin e overexpression reduces infiltrative growth in breast cancer: yet another link between proliferation control and tumor invasion. Cell Cycle 5606-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berk, A. J. 2005. Recent lessons in gene expression, cell cycle control, and cell biology from adenovirus. Oncogene 247673-7685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernstein, E., A. A. Caudy, S. M. Hammond, and G. J. Hannon. 2001. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature 409363-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biederer, C., S. Ries, C. H. Brandts, and F. McCormick. 2002. Replication-selective viruses for cancer therapy. J. Mol. Med. 80163-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bischoff, J. R., D. H. Kirn, A. Williams, C. Heise, S. Horn, M. Muna, L. Ng, J. A. Nye, A. Sampson-Johannes, A. Fattaey, and F. McCormick. 1996. An adenovirus mutant that replicates selectively in p53-deficient human tumor cells. Science 274373-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiocca, E. A., K. M. Abbed, S. Tatter, D. N. Louis, F. H. Hochberg, F. Barker, J. Kracher, S. A. Grossman, J. D. Fisher, K. Carson, M. Rosenblum, T. Mikkelsen, J. Olson, J. Markert, S. Rosenfeld, L. B. Nabors, S. Brem, S. Phuphanich, S. Freeman, R. Kaplan, and J. Zwiebel. 2004. A phase I open-label, dose-escalation, multi-institutional trial of injection with an E1B-attenuated adenovirus, ONYX-015, into the peritumoral region of recurrent malignant gliomas, in the adjuvant setting. Mol. Ther. 10958-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chou, M. M., J. M. Masuda-Robens, and M. L. Gupta. 2003. Cdc42 promotes G1 progression through p70 S6 kinase-mediated induction of cyclin E expression. J. Biol. Chem. 27835241-35247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cobrinik, D. 2005. Pocket proteins and cell cycle control. Oncogene 242796-2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crompton, A. M., and D. H. Kirn. 2007. From ONYX-015 to armed vaccinia viruses: the education and evolution of oncolytic virus development. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 7133-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debbas, M., and E. White. 1993. Wild-type p53 mediates apoptosis by E1A, which is inhibited by E1B. Genes Dev. 7546-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobbelstein, M. 2004. Replicating adenoviruses in cancer therapy. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 273291-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donnellan, R., and R. Chetty. 1999. Cyclin E in human cancers. FASEB J. 13773-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyson, N., and E. Harlow. 1992. Adenovirus E1A targets key regulators of cell proliferation. Cancer Surv. 12161-195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flint, J., and T. Shenk. 1997. Viral transactivating proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 31177-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furstoss, O., G. Manes, and S. Roche. 2002. Cyclin E and cyclin A are likely targets of Src for PDGF-induced DNA synthesis in fibroblasts. FEBS Lett. 52682-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geng, Y., E. N. Eaton, M. Picon, J. M. Roberts, A. S. Lundberg, A. Gifford, C. Sardet, and R. A. Weinberg. 1996. Regulation of cyclin E transcription by E2Fs and retinoblastoma protein. Oncogene 121173-1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geng, Y., Y. M. Lee, M. Welcker, J. Swanger, A. Zagozdzon, J. D. Winer, J. M. Roberts, P. Kaldis, B. E. Clurman, and P. Sicinski. 2007. Kinase-independent function of cyclin E. Mol. Cell 25127-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geng, Y., Q. Yu, E. Sicinska, M. Das, J. E. Schneider, S. Bhattacharya, W. M. Rideout, R. T. Bronson, H. Gardner, and P. Sicinski. 2003. Cyclin E ablation in the mouse. Cell 114431-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giard, D. J., S. A. Aaronson, G. J. Todaro, P. Arnstein, J. H. Kersey, H. Dosik, and W. P. Parks. 1973. In vitro cultivation of human tumors: establishment of cell lines derived from a series of solid tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 511417-1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez, R., W. Huang, R. Finnen, C. Bragg, and S. J. Flint. 2006. Adenovirus E1B 55-kilodalton protein is required for both regulation of mRNA export and efficient entry into the late phase of infection in normal human fibroblasts. J. Virol. 80964-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez, R. A., and S. J. Flint. 2002. Effects of mutations in the adenoviral E1B 55-kilodalton protein coding sequence on viral late mRNA metabolism. J. Virol. 764507-4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodrum, F. D., and D. A. Ornelles. 1997. The early region 1B 55-kilodalton oncoprotein of adenovirus relieves growth restrictions imposed on viral replication by the cell cycle. J. Virol. 71548-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodrum, F. D., and D. A. Ornelles. 1998. p53 status does not determine outcome of E1B 55-kilodalton mutant adenovirus lytic infection. J. Virol. 729479-9490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodrum, F. D., and D. A. Ornelles. 1999. Roles for the E4 orf6, orf3, and E1B 55-kilodalton proteins in cell cycle-independent adenovirus replication. J. Virol. 737474-7488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gossen, M., and H. Bujard. 1992. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 895547-5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham, F. L. 1991. Manipulation of adenovirus vectors, p. 109-128. In E. J. Murray (ed.), Methods in molecular biology, vol. 7. The Humana Press Inc., Clifton, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grand, R. J., M. L. Grant, and P. H. Gallimore. 1994. Enhanced expression of p53 in human cells infected with mutant adenoviruses. Virology 203229-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harada, J. N., and A. J. Berk. 1999. p53-independent and -dependent requirements for E1B-55K in adenovirus type 5 replication. J. Virol. 735333-5344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harada, J. N., A. Shevchenko, D. C. Pallas, and A. J. Berk. 2002. Analysis of the adenovirus E1B-55K-anchored proteome reveals its link to ubiquitination machinery. J. Virol. 769194-9206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harwell, R. M., D. C. Porter, C. Danes, and K. Keyomarsi. 2000. Processing of cyclin E differs between normal and tumor breast cells. Cancer Res. 60481-489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayflick, L., et al. 1962. Preparation of poliovirus vaccines in a human fetal diploid cell strain. Am. J. Hyg. 75240-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hinds, P. W., S. Mittnacht, V. Dulic, A. Arnold, S. I. Reed, and R. A. Weinberg. 1992. Regulation of retinoblastoma protein functions by ectopic expression of human cyclins. Cell 70993-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hobom, U., and M. Dobbelstein. 2004. E1B-55-kilodalton protein is not required to block p53-induced transcription during adenovirus infection. J. Virol. 787685-7697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hubalek, M. M., A. Widschwendter, M. Erdel, A. Gschwendtner, H. M. Fiegl, H. M. Muller, G. Goebel, E. Mueller-Holzner, C. Marth, C. H. Spruck, S. I. Reed, and M. Widschwendter. 2004. Cyclin E dysregulation and chromosomal instability in endometrial cancer. Oncogene 234187-4192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Itamochi, H., J. Kigawa, Y. Kanamori, T. Oishi, C. Bartholomeusz, R. Nahta, F. J. Esteva, N. Sneige, N. Terakawa, and N. T. Ueno. 2007. Adenovirus type 5 E1A gene therapy for ovarian clear cell carcinoma: a potential treatment strategy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 6227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kao, C. C., P. R. Yew, and A. J. Berk. 1990. Domains required for in vitro association between the cellular p53 and the adenovirus 2 E1B 55K proteins. Virology 179806-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keyomarsi, K., S. L. Tucker, and I. Bedrosian. 2003. Cyclin E is a more powerful predictor of breast cancer outcome than proliferation. Nat. Med. 9152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirn, D., R. L. Martuza, and J. Zwiebel. 2001. Replication-selective virotherapy for cancer: biological principles, risk management and future directions. Nat. Med. 7781-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazo, P. A. 1987. Structure, DNaseI hypersensitivity and expression of integrated papilloma virus in the genome of HeLa cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 165393-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lew, D. J., V. Dulic, and S. I. Reed. 1991. Isolation of three novel human cyclins by rescue of G1 cyclin (Cln) function in yeast. Cell 661197-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindahl, T., G. Landberg, J. Ahlgren, H. Nordgren, T. Norberg, S. Klaar, L. Holmberg, and J. Bergh. 2004. Overexpression of cyclin E protein is associated with specific mutation types in the p53 gene and poor survival in human breast cancer. Carcinogenesis 25375-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu, Y., M. E. Costantino, D. Montoya-Durango, Y. Higashi, D. S. Darling, and D. C. Dean. 2007. The zinc finger transcription factor ZFHX1A is linked to cell proliferation by Rb-E2F1. Biochem. J. 40879-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lowe, S. W., and H. E. Ruley. 1993. Stabilization of the p53 tumor suppressor is induced by adenovirus 5 E1A and accompanies apoptosis. Genes Dev. 7535-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ludlow, J. W., and G. R. Skuse. 1995. Viral oncoprotein binding to pRB, p107, p130, and p300. Virus Res. 35113-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mal, A., D. Chattopadhyay, M. K. Ghosh, R. Y. Poon, T. Hunter, and M. L. Harter. 2000. p21 and retinoblastoma protein control the absence of DNA replication in terminally differentiated muscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 149281-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malumbres, M., and M. Barbacid. 2001. To cycle or not to cycle: a critical decision in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 1222-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin, M. E., and A. J. Berk. 1998. Adenovirus E1B 55K represses p53 activation in vitro. J. Virol. 723146-3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mathai, J. P., M. Germain, R. C. Marcellus, and G. C. Shore. 2002. Induction and endoplasmic reticulum location of BIK/NBK in response to apoptotic signaling by E1A and p53. Oncogene 212534-2544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moroy, T., and C. Geisen. 2004. Cyclin E. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 361424-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nevels, M., S. Rubenwolf, T. Spruss, H. Wolf, and T. Dobner. 1997. The adenovirus E4orf6 protein can promote E1A/E1B-induced focus formation by interfering with p53 tumor suppressor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 941206-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nevins, J. R., G. Leone, J. DeGregori, and L. Jakoi. 1997. Role of the Rb/E2F pathway in cell growth control. J. Cell. Physiol. 173233-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Noya, F., C. Balague, N. S. Banerjee, D. T. Curiel, T. R. Broker, and L. T. Chow. 2003. Activation of adenovirus early promoters and lytic phase in differentiated strata of organotypic cultures of human keratinocytes. J. Virol. 776533-6540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ohtsubo, M., A. M. Theodoras, J. Schumacher, J. M. Roberts, and M. Pagano. 1995. Human cyclin E, a nuclear protein essential for the G1-to-S phase transition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 152612-2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O'Shea, C. C., L. Johnson, B. Bagus, S. Choi, C. Nicholas, A. Shen, L. Boyle, K. Pandey, C. Soria, J. Kunich, Y. Shen, G. Habets, D. Ginzinger, and F. McCormick. 2004. Late viral RNA export, rather than p53 inactivation, determines ONYX-015 tumor selectivity. Cancer Cell 6611-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parisi, T., A. R. Beck, N. Rougier, T. McNeil, L. Lucian, Z. Werb, and B. Amati. 2003. Cyclins E1 and E2 are required for endoreplication in placental trophoblast giant cells. EMBO J. 224794-4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parreno, M., J. Garriga, A. Limon, J. H. Albrecht, and X. Grana. 2001. E1A modulates phosphorylation of p130 and p107 by differentially regulating the activity of G1/S cyclin/CDK complexes. Oncogene 204793-4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pilder, S., M. Moore, J. Logan, and T. Shenk. 1986. The adenovirus E1B-55K transforming polypeptide modulates transport or cytoplasmic stabilization of viral and host cell mRNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6470-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Querido, E., P. Blanchette, Q. Yan, T. Kamura, M. Morrison, D. Boivin, W. G. Kaelin, R. C. Conaway, J. W. Conaway, and P. E. Branton. 2001. Degradation of p53 by adenovirus E4orf6 and E1B55K proteins occurs via a novel mechanism involving a Cullin-containing complex. Genes Dev. 153104-3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Querido, E., R. C. Marcellus, A. Lai, R. Charbonneau, J. G. Teodoro, G. Ketner, and P. E. Branton. 1997. Regulation of p53 levels by the E1B 55-kilodalton protein and E4orf6 in adenovirus-infected cells. J. Virol. 713788-3798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rao, X. M., M. T. Tseng, X. Zheng, Y. Dong, A. Jamshidi-Parsian, T. C. Thompson, M. K. Brenner, K. M. McMasters, and H. S. Zhou. 2004. E1A-induced apoptosis does not prevent replication of adenoviruses with deletion of E1b in majority of infected cancer cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 11585-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rao, X. M., X. Zheng, S. Waigel, W. Zacharias, K. M. McMasters, and H. S. Zhou. 2006. Gene expression profiles of normal human lung cells affected by adenoviral E1B. Virology 350418-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Resnitzky, D., M. Gossen, H. Bujard, and S. I. Reed. 1994. Acceleration of the G1/S phase transition by expression of cyclins D1 and E with an inducible system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 141669-1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ries, S., and W. M. Korn. 2002. ONYX-015: mechanisms of action and clinical potential of a replication-selective adenovirus. Br. J. Cancer 865-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rogulski, K. R., S. O. Freytag, K. Zhang, J. D. Gilbert, D. L. Paielli, J. H. Kim, C. C. Heise, and D. H. Kirn. 2000. In vivo antitumor activity of ONYX-015 is influenced by p53 status and is augmented by radiotherapy. Cancer Res. 601193-1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rothmann, T., A. Hengstermann, N. J. Whitaker, M. Scheffner, and H. zur Hausen. 1998. Replication of ONYX-015, a potential anticancer adenovirus, is independent of p53 status in tumor cells. J. Virol. 729470-9478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rowland, B. D., and R. Bernards. 2006. Re-evaluating cell-cycle regulation by E2Fs. Cell 127871-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rowland, B. D., S. G. Denissov, S. Douma, H. G. Stunnenberg, R. Bernards, and D. S. Peeper. 2002. E2F transcriptional repressor complexes are critical downstream targets of p19(ARF)/p53-induced proliferative arrest. Cancer Cell 255-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Santoni-Rugiu, E., J. Falck, N. Mailand, J. Bartek, and J. Lukas. 2000. Involvement of Myc activity in a G1/S-promoting mechanism parallel to the pRb/E2F pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 203497-3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scheffner, M., J. M. Huibregtse, R. D. Vierstra, and P. M. Howley. 1993. The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53. Cell 75495-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scheffner, M., B. A. Werness, J. M. Huibregtse, A. J. Levine, and P. M. Howley. 1990. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell 631129-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schneider-Gadicke, A., and E. Schwarz. 1986. Different human cervical carcinoma cell lines show similar transcription patterns of human papillomavirus type 18 early genes. EMBO J. 52285-2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schwarz, E., U. K. Freese, L. Gissmann, W. Mayer, B. Roggenbuck, A. Stremlau, and H. zur Hausen. 1985. Structure and transcription of human papillomavirus sequences in cervical carcinoma cells. Nature 314111-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shen, Y., G. Kitzes, J. A. Nye, A. Fattaey, and T. Hermiston. 2001. Analyses of single-amino-acid substitution mutants of adenovirus type 5 E1B-55K protein. J. Virol. 754297-4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shenk, T. 2001. Adenoviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 2265-2300. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4 ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shepherd, S. E., J. A. Howe, J. S. Mymryk, and S. T. Bayley. 1993. Induction of the cell cycle in baby rat kidney cells by adenovirus type 5 E1A in the absence of E1B and a possible influence of p53. J. Virol. 672944-2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sieber, T., and T. Dobner. 2007. Adenovirus type 5 early region 1B 156R protein promotes cell transformation independently of repression of p53-stimulated transcription. J. Virol. 8195-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singhal, S., A. Vachani, D. Antin-Ozerkis, L. R. Kaiser, and S. M. Albelda. 2005. Prognostic implications of cell cycle, apoptosis, and angiogenesis biomarkers in non-small cell lung cancer: a review. Clin. Cancer Res. 113974-3986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Spitkovsky, D., P. Jansen-Durr, E. Karsenti, and I. Hoffman. 1996. S-phase induction by adenovirus E1A requires activation of cdc25a tyrosine phosphatase. Oncogene 122549-2554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Takayesu, D., J. G. Teodoro, S. G. Whalen, and P. E. Branton. 1994. Characterization of the 55K adenovirus type 5 E1B product and related proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 75789-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ui-Tei, K., S. Zenno, Y. Miyata, and K. Saigo. 2000. Sensitive assay of RNA interference in Drosophila and Chinese hamster cultured cells using firefly luciferase gene as target. FEBS Lett. 47979-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vigo, E., H. Muller, E. Prosperini, G. Hateboer, P. Cartwright, M. C. Moroni, and K. Helin. 1999. CDC25A phosphatase is a target of E2F and is required for efficient E2F-induced S phase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 196379-6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wersto, R. P., E. R. Rosenthal, P. K. Seth, N. T. Eissa, and R. E. Donahue. 1998. Recombinant, replication-defective adenovirus gene transfer vectors induce cell cycle dysregulation and inappropriate expression of cyclin proteins. J. Virol. 729491-9502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Whyte, P., K. J. Buchkovich, J. M. Horowitz, S. H. Friend, M. Raybuck, R. A. Weinberg, and E. Harlow. 1988. Association between an oncogene and an anti-oncogene: the adenovirus E1A proteins bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Nature 334124-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wienzek, S., J. Roth, and M. Dobbelstein. 2000. E1B 55-kilodalton oncoproteins of adenovirus types 5 and 12 inactivate and relocalize p53, but not p51 or p73, and cooperate with E4orf6 proteins to destabilize p53. J. Virol. 74193-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wuarin, J., V. Buck, P. Nurse, and J. B. Millar. 2002. Stable association of mitotic cyclin B/Cdc2 to replication origins prevents endoreduplication. Cell 111419-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yew, P. R., and A. J. Berk. 1992. Inhibition of p53 transactivation required for transformation by adenovirus early 1B protein. Nature 35782-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang, H. S., A. A. Postigo, and D. C. Dean. 1999. Active transcriptional repression by the Rb-E2F complex mediates G1 arrest triggered by p16INK4a, TGFbeta, and contact inhibition. Cell 9753-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhao, T., X. M. Rao, X. Xie, L. Li, T. C. Thompson, K. M. McMasters, and H. S. Zhou. 2003. Adenovirus with insertion-mutated E1A selectively propagates in liver cancer cells and destroys tumors in vivo. Cancer Res. 633073-3078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zheng, X., X. M. Rao, C. Snodgrass, M. Wang, Y. Dong, K. M. McMasters, and H. S. Zhou. 2005. Adenoviral e1a expression levels affect virus-selective replication in human cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 41255-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zheng, X., X. M. Rao, C. L. Snodgrass, K. M. McMasters, and H. S. Zhou. 2006. Selective replication of E1B55K-deleted adenoviruses depends on enhanced E1A expression in cancer cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 13572-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhou, H., and A. Beaudet. 2000. A new vector system with inducible cell line E2T for production of safer and higher titer adenoviral vectors. Virology 275348-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhou, H., W. O'Neal, N. Morral, and A. L. Beaudet. 1996. Development of a complementing cell line and a system for construction of adenovirus vectors with E1 and E2a deleted. J. Virol. 707030-7038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]