Abstract

Eighty years ago, Alexander Fleming discovered antibacterial activity in the asexual mold Penicillium, and the strain he studied later was replaced by an overproducing isolate still used for penicillin production today. Using a heterologous PCR approach, we show that these strains are of opposite mating types and that both have retained transcriptionally expressed pheromone and pheromone receptor genes required for sexual reproduction. This discovery extends options for industrial strain improvement programs using conventional genetical approaches.

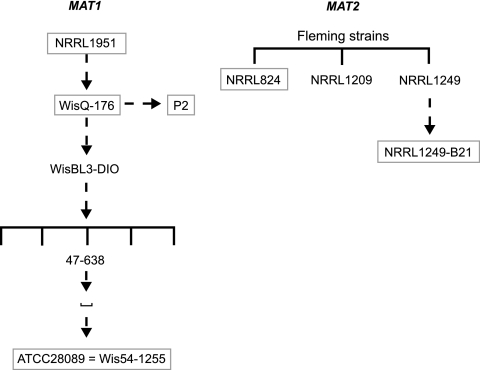

The observation that a mold could inhibit bacterial growth is perhaps the most important breakthrough in the history of therapeutic medicine. In 1928, Alexander Fleming noticed that the growth of staphylococcus colonies growing near a contaminating mold colony was disrupted. The following year, he published a paper describing the mold as Penicillium notatum and terming the active compound penicillin (15). The finding that penicillin was not toxic to animals only increased interest, and this was followed by the attempts of H. W. Florey, N. G. Heatley, and E. B. Chain, working at Oxford University, to purify penicillin. Later, D. C. Hodgkin and B. Low went on to determine its β-lactam structure using X-ray crystallography. However, it was not until 1941 that the first clinical trials with penicillin were undertaken (1), and since chemical synthesis was not found to be possible, fermentation became the commercial source of penicillin. Unfortunately, Fleming's original P. notatum strain (NRRL1249B21) produces only low levels of penicillin, so that strain improvement and large-scale production became essential. However, British industry was unable to produce the large amounts of required penicillin due to the restraints on resources caused by World War II. Therefore, Florey and Heatley went to the United States to raise the interest of the American pharmaceutical industry and U.S. Department of Agriculture in penicillin production. Here the problem of large-scale penicillin production was solved when Penicillium chrysogenum (Thom) strain NRRL1951 was isolated from a moldy cantaloupe obtained in a Peoria, IL, market (33). Strain WisQ-176, a derivative of strain NRRL1951, was obtained by conventional strain improvement programs and is the ancestor of all strains used today for biotechnical penicillin production (12, 18), with a total world market of about $8 billion (2) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Genealogy of P. chrysogenum strains containing either the MAT1 or MAT2 idiomorph. Strains used in this study are boxed.

The ability to mate fungi under controlled laboratory conditions is a valuable tool for genetic analysis and classical strain improvement (29). In ascomycetes, mating typically occurs between morphologically identical partners that are distinguished by their mating type. In most cases a single mating-type (MAT) locus conferring mating behavior consists of dissimilar DNA sequences in the mating partners, termed the MAT1 and MAT2 idiomorphs. MAT1 contains a gene encoding a protein with an alpha-box domain, whereas MAT2 carries a gene encoding a protein with a high-mobility group (HMG) domain. In addition to these genes, other genes may also be present at the MAT locus (6, 10, 29, 37, 38). In contrast to self-sterile (heterothallic) fungi, self-fertile (homothallic) filamentous ascomycetes contain genes indicative of both mating types in the same genome, either linked or unlinked (17, 28, 32, 34, 40).

The ubiquitous genus Penicillium consists of numerous important, apparently asexual species. Unfortunately, due to its asexuality, Penicillium is difficult to improve for penicillin production by conventional genetics approaches. However, analysis of the complete genome sequences of the asexual human pathogens Aspergillus fumigatus and Penicillium marneffei, relatives of P. chrysogenum, revealed the presence of genes associated with sexual reproduction, including mating-type genes and genes for pheromone production and detection (17, 25, 27, 39).

Here we present the discovery of transcriptionally expressed mating-type genes in P. chrysogenum, the industrial producer of the β-lactam antibiotic penicillin. Moreover, we find homologs of pheromone and pheromone receptor genes that are known to function in mating and signaling in sexually reproducing filamentous ascomycetes. To the best of our knowledge, P. chrysogenum is the first industrial fungus for which transcriptionally expressed mating-type genes were discovered. Our findings open up the possibility of inducing mating and sexual reproduction for alternative strain improvement strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains, growth conditions, and preparation of nucleic acids.

A list of all P. chrysogenum isolates used, with source details, is provided in Table 1. Strains were routinely maintained at 27°C on CCM complete culture medium (0.3% [wt/vol] sucrose, 0.05% [wt/vol] NaCl, 0.05% [wt/vol] K2HPO4, 0.05% [wt/vol] MgSO4, 0.001% [wt/vol] FeSO4, 0.5% [wt/vol] tryptic soy broth, 0.1% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 0.1% [wt/vol] meat extract, 1.5% [wt/vol] dextrine, pH 6.9 to 7.1). For DNA and RNA extraction, P. chrysogenum strains were grown at 27°C and 130 rpm for 4 days in liquid CCM medium. After growth, resulting mycelia were removed, flash frozen, and ground under liquid nitrogen prior to DNA and RNA extraction. Fungal genomic DNA and RNA were extracted with phenol-chloroform and chloroform/isoamyl alcohol methods as previously described (24).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study including mating types, descriptions, and sources

| Strain or isolate | Mating type | Locus of isolation or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRRL1951 | MAT-1 | Moldy cantaloupe fruit; United States | ARS culture collection (NRRL), Peoria, IL |

| ATCC 28089, ATCC 16521, WisQ-176 P2 | MAT-1 | Derivatives of strain NRRL1951, obtained by random mutagenesis | Sandoz GmbH, Kundl, Austria |

| NRRL832 | MAT-1 | Contamination of must; Belgium | CBS fungus database, The Netherlands |

| NRRL807 | MAT-1 | Contamination from cheese; United States | CBS fungus database, The Netherlands |

| DAOM193710 | MAT-1 | Contamination from cheese; United States | 35 |

| DAOM155627 | MAT-1 | Contamination from paper; Canada | 35 |

| NRRL1249B21 | MAT-2 | Fleming strain (George A. Harrop) | DSMZ, Germany |

| NRRL824 | MAT-2 | Fleming strain (Charles Thom collection) | CBS fungus database, The Netherlands |

| DSM62858 | MAT-2 | Contamination from optical glass | DSMZ, Germany |

| DAOM155628 | MAT-2 | Contamination from paper; Canada | 35 |

| DAOM216701 | MAT-2 | Sesanum indicum; Korea | 35 |

| DAOM59494C | MAT-2 | Substrate unknown; Honduras | 35 |

PCR amplification and cloning of P. chrysogenum genes.

In an attempt to detect P. chrysogenum isolates containing a MAT1 or MAT2 idiomorph, primers Afapn2-f (5′-ACATTTATATGGGCTAGCGATTGGAAC-3′) and Afsla2-r (5′-CGTCAACGCCT TGGAGAGATGCGC-3′) were designed based on conserved region sequences of the A. fumigatus APN2 and SLA2 genes, respectively. The primers were used in a heterologous PCR screen of 12 P. chrysogenum isolates (Table 1) with 50-μl reaction mixtures containing 250 μg genomic DNA, 10 pmol of each primer, 1 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 5 U HotMaster Taq polymerase (5′ Prime, Germany). Cycle parameters were 2 min at 94°C, 40 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 5 min at 68°C, and a final step of 15 min at 25°C. Amplicons of strains ATCC 28089 and NRRL1249B21 of predicted sizes for the idiomorphs were cloned into the vector pDrive (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendation, and the insert sequence was determined (MWG-Biotech, Germany).

Extracted genomic DNA of P. chrysogenum was further used as a template for the amplification of a pheromone precursor gene using primers Appg1-f (5′-GGCTGCCGCC GCCGTCCAGGC-3′) and Appg1-r (5′-CGCTTGGCCTTGGCACAACCCTGGCC-3′) based on sequence comparison of the ppg1 genes of Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus terreus, and A. fumigatus. In order to amplify pheromone receptor genes from P. chrysogenum, primers were designed according to conserved regions of the A. fumigatus preA gene (AfpreA-f [5′-TGGCCCACGGACGATGTGGATTCATGGTGG-3′] and AfpreA-r [5′-AAGGAAAAATAGACGCAGGAATCTGGACTT-3′]) and the preB gene (AfpreB-f [5′-TGGCTAGAGAGTGCCGCCACGAATATC-3′] and AfpreB-r [5′-TGGGATGGTCA TAGTTTGGCAACCCAT-3′]), respectively. PCR was conducted using a total volume of 50 μl containing 250 μg genomic DNA, 10 pmol of each primer, 1 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 5 U Taq polymerase (5′ Prime, Germany). PCR conditions were as follows: 2 min at 94°C, 40 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 48 to 50°C, and 1.5 min at 72°C, and a final step of 15 min at 25°C. The resulting amplicons were sequenced (MWG-Biotech, Germany), and the arising data were analyzed using the BLAST program.

The full-length sequences of the genes were derived from cDNA clones detected in a P. chrysogenum cDNA library (Sandoz GmbH, Kundl, Austria) that was screened according to previously published procedures (22).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR for expression analyses.

For use in semiquantitative RT-PCR, cDNA synthesis was carried out as previously described (24) with the following modifications: 2-μg aliquots of total RNA were treated with DNase I (Invitrogen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and reverse transcription (RT) was performed with 400 U Superscript II (Invitrogen, Germany) and deoxynucleoside triphosphates at a concentration of 0.33 mM. As a control for successful DNase treatment, each reverse transcription was carried out twice, once with and once without reverse transcriptase. All samples were used as templates for the expression analysis of the MAT-1 and MAT-2 genes and the pheromone precursor and receptor genes Pcppg1, Pcpre1, and Pcpre2 using the following primers: (i) for the MAT-1 gene primers, MAT-1-f (5′-CTTCGTCCATTGAACTCTTTTATG-3′) and MAT-1-r (5′-ATCCCAAC CAGCCATCCTGAGATA-3′); (ii) for the MAT-2 gene primers, MAT-2-f (5′-CCAAGT CTATCCACGAGGCTG-3′) and MAT-2-r (5′-GCAGGCAGTTGGCACGGGAAC-3′); (iii) for the Pcppg1 gene primers, Pcppg1-f (5′-TTACTCGTCATCCTCTTCCTCGA-3′) and Pcppg1-r (5′-ATGAAGTTCACCTCCGTCGTC-3′); (iv) for the Pcpre1 gene primers, Pcpre1-f (5′-GTTCTGCGTGGCTGTTCCAGT-3′) and Pcpre1-r (5′-GGGATGCCAGG GGAGGGAGAGCAT-3′); and (v) for the Pcpre2 gene primers, Pcpre2-f (5′-GTCACTAAG CTCGGATTCGCC-3′) and Pcpre2-r (5′-CGATTGAATTGTTCCTTTGAAC-3′). RT-PCR was performed in a volume of 50 μl with HotMaster Taq polymerase (5′ Prime, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. PCR conditions were as follows: 2 min at 94°C, 40 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 53 to 55°C, and 5 min at 68°C, and a final step of 15 min 25°C.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the mating-type genes and the pheromone precursor and receptor genes have been deposited in the EMBL database under the accession numbers indicated: MAT-1, AM904544; MAT-2, AM904545; Pcppg1, AM904541; Pcpre1, AM904542; and Pcpre2, AM904543.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of opposite mating-type loci in Fleming's and penicillin production strains.

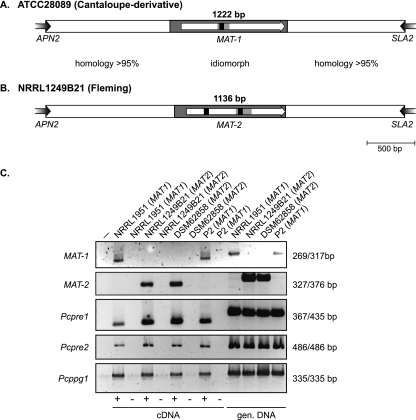

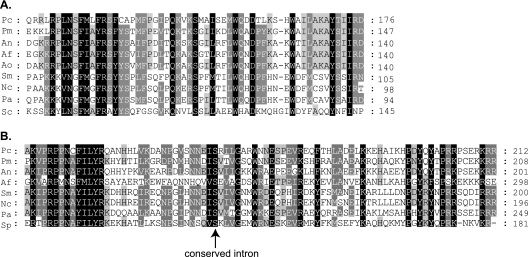

The APN2 gene, encoding a putative DNA lyase, and the SLA2 gene, encoding a cytoskeleton assembly control factor, have been found neighboring MAT loci in A. fumigatus and many other ascomycetes (14, 16, 17). Therefore, to determine whether mating-type genes are also present in the industrially relevant fungus P. chrysogenum, we designed primers corresponding to conserved regions of the A. fumigatus APN2 and SLA2 genes, respectively. Genomic DNA from Fleming's original strain, NRRL1249B21, and from 11 other isolates, including ATCC 28089, a derivative of the cantaloupe strain NRRL1951 (Table 1), was used. This strain most probably belongs to the same taxa as the original Fleming isolate, since both strains contain completely identical internal transcribed spacer 2 sequences (data not shown). This sequence is highly suitable for evaluating whether the taxa of a species can potentially interbreed and was already used with numerous eukaryotes (8). Two different types of amplicons of 3.6 and 3.7 kb were obtained. Six isolates, including the cantaloupe strain NRRL1951, generated the larger amplicon, while the other six, including the Fleming strain NRRL1249B21, generated the smaller one. Sequencing of the larger amplicon of strain ATCC 28089 revealed the presence of a putative 1,077-bp MAT-1 gene whose open reading frame (ORF) is interrupted by a 48-bp intron; splicing of this intron was confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 2A and C). The putative MAT-1 gene encodes a predicted protein of 342 amino acid residues harboring a conserved alpha-box domain (Fig. 3A). Surprisingly, sequencing of the smaller amplicon of the Fleming strain (NRRL1249B21) revealed a homology to other fungal MAT2 loci. This identified MAT2 locus is 1,136 bp in size and contains a single ORF interrupted by two introns of 53 bp and 50 bp, splicing of which was also confirmed by means of RT-PCR (Fig. 2B and C). The ORF encodes a protein of 303 amino acid residues with a conserved HMG-DNA-binding domain with an amino acid identity of 37 to 59% to HMG mating-type proteins from other ascomycetes. The second intron of the P. chrysogenum MAT-2 gene is located at a conserved position in a serine (S) codon of the HMG domain (Fig. 3B) and thus is at the same position as in all of the ascomycete HMG mating-type genes known to date (11). Similar to the structural organization of mating-type loci in many sexually reproducing filamentous ascomycetes, highly conserved flanking regions (95.8% identical nucleotides within a 1,318-bp upstream and 1,217-bp downstream flanking region) were found upstream and downstream of the MAT idiomorphs (Fig. 2A and B). Both P. chrysogenum mating-type loci are directly flanked by APN2 and SLA2. This is in accordance with the mating-type organization of A. fumigatus and other asexual species of the genus Aspergillus (14, 25) but clearly different from those of the recently characterized mating-type idiomorphs of the human pathogens Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, and Coccidioides posadasii. In H. capsulatum, the cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIa gene COX13 instead of the APN2 gene is located upstream of the mating-type locus, whereas in the Onygenales members C. immitis and C. posadasii, the dissimilarity between the two idiomorphs expands beyond the HMG and alpha-box regions and encompasses the adjacent APN2 and COX13 genes (16, 21). In contrast to the case with A. fumigatus, P. marneffei, C. immitis, and C. posadasii (16, 21, 39), no additional ORFs could be identified within the mating-type idiomorphs of P. chrysogenum.

FIG. 2.

Mating-type locus of Penicillium chrysogenum. (A and B) Schematic illustration of the mating-type idiomorphs and their flanking regions. Idiomorphs are presented as gray boxes and their flanking regions as white boxes. The positioning and transcriptional direction of the mating-type genes in each idiomorph are indicated by an arrow, and introns are shown in black. (A) MAT1 idiomorph of strain ATCC 28089 (accession no. AM904544). The relative position of the alpha-box domain of MAT-1 is indicated. (B) MAT2 idiomorph of strain NRRL1249B21 (accession no. AM904545). The relative position of the HMG domain of MAT-2 is indicated. (C) Expression of mating-type genes and genes involved in sexual reproduction in P. chrysogenum. RNA transcripts (cDNA) either with (+) or without (−) reverse transcriptase were amplified by RT-PCR. PCR amplification of genomic DNA (gen. DNA) was used as a positive control. The strain designation and mating type are indicated above each lane; sizes of cDNA and genomic DNA amplicons are given on the right.

FIG. 3.

Conserved domains of mating-type proteins from P. chrysogenum. (A) Multiple alignment of the alpha-box region of the P. chrysogenum MAT1 protein with alpha-box proteins from other ascomycetes. Abbreviations and accession numbers (Ac.) are as follows: Pc, Penicillium chrysogenum (Ac. AM904544); Pm, Penicillium marneffei (Ac. Q1A3S7); An, Aspergillus nidulans (Ac. Q7Z896); Af, Aspergillus fumigatus (Ac. AAX83123.1); Ao, Aspergillus oryzae (Ac. Q2U537); Sm, Sordaria macrospora (Ac. O42837); Nc, Neurospora crassa (Ac. P19392); Pa, Podospora anserina (Ac. P35692); Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Ac. YP_087100.1). (B) Multiple alignment of the HMG domain of the P. chrysogenum MAT2 protein with HMG mating-type proteins from other ascomycetes. For abbreviations and accession numbers, see panel A; also, for Pc,Ac. AM904545; for Pm, Ac. ABC68485.1; for An, Ac. Q7Z8M2; for Af, Ac. XP_751590.1); for Sm, Ac. CAA71624.1; for Nc, Ac. P36981; for Pa, Ac. P35693; for Sp (Schizosaccharomyces pombe), Ac. P10840. The position of a conserved intron is indicated by an arrow.

Equal distribution of MAT1 and MAT2 loci in geographically separated P. chrysogenum isolates.

To test whether the remaining 10 strains carry either the MAT1 or MAT2 locus, specific primer pairs amplifying either the HMG domain or the conserved alpha-box domain were designed. The detection of six MAT1 strains and six MAT2 strains confirmed the presence of both mating types in equal proportions (Table 1). A one-to-one distribution of MAT1:MAT2 strains indicates that occasionally sexual reproduction occurs in P. chrysogenum. Similar results were also obtained for the pathogens A. fumigatus (25) and Coccidioides (21). Moreover, investigation of the alpha-box and HMG domain genes provided no evidence for loss-of-function mutations. Further RT-PCR analyses showed that both genes are expressed (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data suggest that P. chrysogenum has the potential to reproduce sexually. This finding prompted us to search for homologs of pheromone and pheromone receptor genes that function in mating and pheromone signaling in sexually reproducing filamentous ascomycetes (19, 23, 25, 26, 30, 36).

Both mating-type strains carry transcriptionally expressed pheromone and pheromone receptor genes.

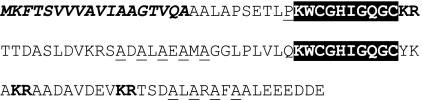

Two different classes of pheromones are known to be involved in sexual reproduction in outbreeding and in self-sterile filamentous ascomycetes (9, 19, 23, 36). One class of genes encodes peptide pheromone precursors that contain multiple copies of the mature peptides flanked by protease cleavage sites, while the other class of pheromone genes encodes a small protein with a CAAX motif at the C terminus. This motif is expected to produce a mature lipopeptide pheromone with a C-terminal carboxy methyl isoprenylated cysteine (7). To identify any putative pheromone precursors encoded by the P. chrysogenum genome, primers based on conserved-region sequences of the peptide pheromone precursor gene ppgA of A. fumigatus were used for PCR. Sequencing of the obtained amplicon of 214 bp revealed a similarity of 57.1% with the ppgA gene of A. fumigatus. Subsequently, a screen of a P. chrysogenum cDNA library led to the isolation of a putative P. chrysogenum gene encoding a 111-amino-acid peptide pheromone precursor. The identified P. chrysogenum gene was named Pcppg1. Within the polypeptide encoded by this gene, two identical repeats could be identified. The two repeats encode the decapeptide amino acid sequence KWCGHIGQGC (Fig. 4). The decapeptide sequence bears strong similarity to pheromones from other filamentous ascomycetes (31). Interestingly, a hydrophobic signal sequence was detected within the N terminus of P. chrysogenum PPG1. Therefore, the putative pheromone is most likely secreted from the cell via the classical secretion pathway. In A. fumigatus and other species of the genus Aspergillus, extensive TBLASTN analysis failed to identify a homolog encoding a lipopeptide pheromone. We therefore did not try to identify a P. chrysogenum lipopeptide pheromone gene by means of heterologous PCR. However, using the same strategy as for the isolation of the Pcppg1 gene, we were able to identify two pheromone receptor genes from P. chrysogenum. The gene products of Pcpre1 and Pcpre2 are predicted to have seven transmembrane spanning domains and displayed a high level of amino acid identity with the a-factor receptor Ste3p and the α-factor receptor Ste2p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, respectively, as well as with pheromone receptors of filamentous ascomycetes (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). Using the RT-PCR approach, we demonstrated that both the pheromone and receptor genes are expressed in strains of both mating types (Fig. 2C), an observation similar to that with A. fumigatus (25).

FIG. 4.

Amino acid sequence of the peptide pheromone from P. chrysogenum (accession no. AM904541). Repeats are shown in white and boxed in black, Kex2 processing sites (KR) indicated in bold, putative STE13 processing sites are underlined, and the hydrophobic leader sequence is indicated in bold italics.

Attempts to mate strains with opposite mating-type loci.

The results of our transcriptional expression data suggest the existence of a heterothallic sexual cycle in P. chrysogenum. This finding opens up the possibility of inducing mating and sexual reproduction in P. chrysogenum, as was previously shown for the typical “asexual” yeast, Candida albicans (3). While in C. albicans the discovery of mating-type genes led to the development of procedures for the mating of strains with opposite mating-type loci, similar attempts failed so far with the filamentous fungus A. fumigatus. We similarly tried to mate P. chrysogenum strains with opposite mating types (B. Hoff et al., unpublished data). This was done by combining all strains listed in Table 1 under different physiological conditions. For example, the plates were incubated in the dark as well as in light, and the cultures were grown on different rich media as well as minimal media. Moreover, we used sealed or unsealed plates of P. chrysogenum, conditions known to promote or prevent sexual differentiation in A. nidulans (4). However, microscopic analyses of plates after more than 10 weeks of incubation did not indicate the generation of cleistothecia. In contrast, teleomorphs of Penicillium belonging to the genus Eupenicillium (13) generated cleistothecia and ascospores on complete medium in the dark under limited air exchange after 2 weeks of incubation. At this point, it should be noted that all P. chrysogenum strains were derived from type culture collections and might have lost fertility during long storage. For the heterothallic H. capsulatum, it has been reported that fertility is rapidly lost during laboratory passage, and it has been suggested that selective pressures may serve to maintain fertility in the environment (16, 20). Moreover, despite molecular verification, mating compatibility tests of H. capsulatum strains of different mating types did not result in the formation of an ascocarp and ascospores (5). Thus, it will be more promising to repeat the P. chrysogenum experiments with strains directly isolated from nature.

Furthermore, we tested whether penicillin production of a given strain was changed in the presence of the opposite mating-type partners. Since only a high-producer strain and derivatives thereof with identical mating-type loci (MAT1) were available (Table 1), we had to use wild-type strains for these experiments. MAT2 strains, however, produce only low levels of penicillin. Therefore, moderate changes in antibiotic production were hard to detect by bioassays or high-performance liquid chromatography analysis. Further experiments will be required to demonstrate sexual reproduction in P. chrysogenum. A successful outcome of these attempts will extend the options for manipulating P. chrysogenum genetically and should ultimately provide the opportunity to generate genetically engineered penicillin production strains with novel metabolic properties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ingeborg Godehardt, Kerstin Kalkreuter, and Stefanie Mertens for technical assistance and Hubert Kürnsteiner, Thomas Specht, and Ivo Zadra (Kundl, Austria) for helpful discussion.

We acknowledge financial support from Sandoz GmbH (Kundl, Austria) and from the Christian Doppler Society (Vienna, Austria).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 January 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham, E. 1990. Selective reminiscences of beta-lactam antibiotics: early research on penicillin and cephalosporins. Bioessays 12601-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barber, S. M., U. Giesecke, A. Reichert, and W. Minas. 2004. Industrial enzymatic production of cephalosporin-based β-lactams. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 88179-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett, R. J., and A. D. Johnson. 2005. Mating in Candida albicans and the search for a sexual cycle. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59233-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braus, H. G., S. Krappmann, and S. E. Eckert. 2002. Sexual development in ascomycetes: fruit body formation of Aspergillus nidulans, p. 215-244. In H. D. Osiewacz (ed.), Molecular biology of fungal development. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY.

- 5.Bubnick, M., and A. G. Smulian. 2007. The MAT1 locus of Histoplasma capsulatum is responsive in a mating type-specific manner. Eukaryot. Cell 6616-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler, G. 2007. The evolution of MAT: the ascomycetes, p. 3-18. In J. Heitman, J. W. Kronstad, J. W. Taylor, and L. A. Casselton (ed.), Sex in fungi. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 7.Chen, P., S. K. Sapperstein, J. C. Choi, and S. Michaelis. 1997. Biogenesis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mating pheromone a-factor. J. Cell Biol. 136251-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman, A. W. 2007. Pan-eukaryote ITS2 homologies revealed by RNA secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 353322-3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coppin, E., C. de Renty, and R. Debuchy. 2005. The function of the coding sequences for the putative pheromone precursors in Podospora anserina is restricted to fertilization. Eukaryot. Cell 4407-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coppin, E., R. Debuchy, S. Arnaise, and M. Picard. 1997. Mating type and sexual development in ascomycetes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61411-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debuchy, R., and B. G. Turgeon. 2006. Mating-type structure, evolution, and function in euascomycetes, p. 293-324. In U. Kües and R. Fischer (ed.), The Mycota, vol. I: growth, differentiation and sexuality. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- 12.Demain, A. L., and P. R. Elander. 1999. The β-lactam antibiotics: past, present and future. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 755-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domsch, K. H., W. Gams, and T. H. Anderson. 2007. Compendium of soil fungi. IHW-Verlag, Eching, Germany.

- 14.Dyer, P. S. 2007. Sexual reproduction and significance of MAT in the aspergilli, p. 123-142. In J. Heitman, J. W. Kronstad, J. W. Taylor, and L. A. Casselton (ed.), Sex in fungi. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 15.Fleming, A. 1929. On the antibacterial action of cultures of a penicillium with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenza. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 10226-236. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser, J. A., J. E. Stajich, E. J. Tarcha, G. T. Cole, D. O. Inglis, A. Sil, and J. Heitman. 2007. Evolution of the mating type locus: insights gained from the dimorphic primary fungal pathogens Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, and Coccidioides posadasii. Eukaryot. Cell 6622-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galagan, J. E., S. E. Calvo, C. Cuomo, L. J. Ma, J. R. Wortman, S. Batzoglou, S. I. Lee, M. Bastürkmen, C. C. Spevak, J. Clutterbuck, V. Kapitonov, J. Jurka, C. Scazzocchio, M. Farman, J. Butler, S. Purcell, S. Harris, G. H. Braus, O. Draht, S. Busch, C. D'Enfert, C. Bouchier, G. H. Goldman, D. Bell-Pedersen, S. Griffiths-Jones, J. H. Doonan, J. Yu, K. Vienken, A. Pain, M. Freitag, E. U. Selker, D. B. Archer, M. A. Peñalva, B. R. Oakley, M. Momany, T. Tanaka, T. Kumagai, K. Asai, M. Machida, W. C. Nierman, D. W. Denning, M. Caddick, M. Hynes, M. Paoletti, R. Fischer, B. Miller, P. Dyer, M. S. Sachs, S. A. Osmani, and B. W. Birren. 2005. Sequencing of Aspergillus nidulans and comparative analysis with A. fumigatus and A. oryzae. Nature 4381105-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller, N. P., G. Turner, and J. W. Bennett. 2005. Fungal secondary metabolism—from biochemistry to genomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3937-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, H., and K. A. Borkovich. 2006. Pheromones are essential for male fertility and sufficient to direct chemotropic polarized growth of trichogynes during mating in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 5544-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon-Chung, K. J., R. J. Weeks, and H. W. Larsh. 1974. Studies on Emmonsiella capsulata (Histoplasma capsulatum). II. Distribution of the two mating types in 13 endemic states of the United States. Am. J. Epidemiol. 9944-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandel, M. A., B. M. Barker, S. Kroken, S. D. Rounsley, and M. J. Orbach. 2007. Genomic and population analyses of the mating type loci in Coccidioides species reveal evidence for sexual reproduction and gene acquisition. Eukaryot. Cell 61189-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masloff, S., S. Jacobsen, S. Pöggeler, and U. Kück. 2002. Functional analysis of the C6 zinc finger gene pro1 involved in fungal sexual development. Fungal Genet. Biol. 36107-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayrhofer, S., J. M. Weber, and S. Pöggeler. 2006. Pheromones and pheromone receptors are required for proper sexual development in the homothallic ascomycete Sordaria macrospora. Genetics 1721-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nowrousian, M., C. Ringelberg, J. C. Dunlap, J. J. Loros, and U. Kück. 2005. Cross-species microarray hybridization to identify developmentally regulated genes in the filamentous fungus Sordaria macrospora. Mol. Genet. Genomics 273137-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paoletti, M., C. Rydholm, E. U. Schwier, M. J. Anderson, G. Szakacs, F. Lutzoni, J. P. Debeaupuis, J. P. Latgé, D. W. Denning, and P. S. Dyer. 2005. Evidence for sexuality in the opportunistic fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Curr. Biol. 151242-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paoletti, M., F. A. Seymour, M. J. Alcocer, N. Kaur, A. M. Calvo, D. B. Archer, and P. S. Dyer. 2007. Mating type and the genetic basis of self-fertility in the model fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Curr. Biol. 211384-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pöggeler, S. 2002. Genomic evidence for mating abilities in the asexual pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Curr. Genet. 42153-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pöggeler, S. 2007. MAT and its role in the homothallic ascomycete Sordaria macrospora, p. 171-188. In J. Heitman, J. W. Kronstad, J. W. Taylor, and L. A. Casselton (ed.), Sex in fungi. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 29.Pöggeler, S. 2001. Mating-type genes for classical strain improvements of ascomycetes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 56589-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pöggeler, S., and U. Kück. 2001. Identification of transcriptionally expressed pheromone receptor genes in filamentous ascomycetes. Gene 2809-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pöggeler, S., M. Nowrousian, and U. Kück. 2006. Fruiting body development in ascomycetes, p. 325-355. In U. Kües and R. Fischer (ed.), The Mycota, vol. I: growth, differentiation and sexuality. I. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- 32.Pöggeler, S., S. Risch, U. Kück, and H. D. Osiewacz. 1997. Mating-type genes from the homothallic fungus Sordaria macrospora are functionally expressed in a heterothallic ascomycete. Genetics 147567-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raper, K. B., D. F. Alexander, and R. D. Coghill. 1944. Penicillin. II. Natural variation and penicillin production in Penicillium notatum and allied species. J. Bacteriol. 48639-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rydholm, C., P. S. Dyer, and F. Lutzoni. 2007. DNA sequence characterization and molecular evolution of MAT1 and MAT2 mating-type loci of the self-compatible ascomycete mold Neosartorya fischeri. Eukaryot. Cell 6868-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott, J., W. A. Untereiner, B. Wong, N. A. Straus, and D. Malloch. 2004. Genotypic variation in Penicillium chrysogenum from indoor environments. Mycologia 961095-1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seo, J. A., K. H. Han, and J. H. Yu. 2004. The gprA and gprB genes encode putative G protein-coupled receptors required for self-fertilization in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 531611-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turgeon, B. G., and R. Debuchy. 2007. Cochliobolus and Podospora: mechanisms of sex determination and the evolution of reproductive lifestyle, p. 93-121. In J. Heitman, J. W. Kronstad, J. W. Taylor, and L. A. Casselton (ed.), Sex in fungi. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 38.Turgeon, B. G., and O. C. Yoder. 2000. Proposed nomenclature for mating type genes of filamentous ascomycetes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woo, P. C., K. T. Chong, H. Tse, J. J. Cai, C. C. Lau, A. C. Zhou, S. K. Lau, and K. Y. Yuen. 2006. Genomic and experimental evidence for a potential sexual cycle in the pathogenic thermal dimorphic fungus Penicillium marneffei. FEBS Lett. 5803409-3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yun, S. H., M. L. Berbee, O. C. Yoder, and B. G. Turgeon. 1999. Evolution of the fungal self-fertile reproductive life style from self-sterile ancestors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 965592-5597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.