Abstract

When the abundance of the FOX1 gene product is reduced, Chlamydomonas cells grow poorly in iron-deficient medium, but not in iron-replete medium, suggesting that FOX1-dependent iron uptake is a high-affinity pathway. Alternative pathways for iron assimilation, such as those involving ZIP family transporters IRT1 and IRT2, may be operational.

Iron is an essential nutrient for all forms of life because of its role as a catalyst in redox reactions that are the basis of life. Yet, because of the reduced solubility of ferric salts (the predominant species in the aerobic world), particularly in an alkaline soil environment, the bioavailability of iron can be poor and, hence, a limitation to life (6). Accordingly, the assimilation pathways include mechanisms for mobilizing iron from inaccessible forms, plus mechanisms for uptake.

Previously, we and others identified several genes that might constitute an iron uptake pathway in Chlamydomonas based on their increased expression in iron-poor growth conditions and/or on their sequence relationship to components of iron assimilation in fungi, plants, or animals (1, 14). These include FRE1, encoding a ferrireductase; FOX1, encoding a putative multicopper oxidase; FTR1, encoding a ferric transporter; FEA1/2, encoding abundant periplasmic proteins; and IRT1/2, encoding ZIP-family transporters. FRE1 and the IRT proteins are most-closely related to components found in the iron assimilation pathway of plants; FTR1-like proteins are found primarily in the fungi, although a homolog does occur in Physcomitrella; the FEA proteins are only in algae and a dinoflagellate; and FOX1 is a domain-rearranged version of animal ferroxidases, like ceruloplasmin and hephaestin, that function in iron homeostasis (1, 5, 14, 21, 23). Except for the FEA proteins, the evidence for the participation of these components in iron assimilation in Chlamydomonas is indirect. Furthermore, the role of a FOX1/FTR1-type transporter (analogous to fungal iron uptake components) versus that of the IRT-type transporter is not clear. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, there are multiple pathways that together participate in iron uptake, so that the organism can use a variety of iron sources supplied at a range of concentrations (reviewed in references 13 and 19).

FOX1 is localized to the plasma membrane of Chlamydomonas; its sequence indicates that it is a multicopper oxidase, and therefore, by analogy to S. cerevisiae Fet3p, FOX1 is proposed to oxidize ferrous to ferric iron for uptake by FTR1 (9, 14, 24). In S. cerevisiae and in animals, nutritional copper deficiency or genetic defects that result in copper deficiency have an impact also on iron nutrition because of the function of the multicopper oxidases, Fet3p and ceruloplasmin, in iron metabolism (reviewed in references 2, 7, and 11). Yet in our previous work, we have found that copper-deficient wild-type Chlamydomonas cells are not iron-deficient even when iron is supplied at nutritionally limiting concentrations (14). Nevertheless, this is not the case in the crd2 mutant and in a wild-type strain from another laboratory, where there is a dependence on copper for iron uptake (4, 8). The crd2 mutant is indistinguishable from the wild type in copper-replete medium, but in copper-deficient medium, the cells grow poorly. The phenotype is exacerbated in low-iron conditions and rescued by excess iron, suggesting a role for CRD2 in iron homeostasis. FOX1 and FTR1 show increased expression in copper-deficient crd2 strains relative to their expression levels in copper-deficient wild-type strains, indicative of internal iron deficiency. We suggested that CRD2 might encode either a copper-independent backup for FOX1 or a “facilitator” of the assembly of the polynuclear copper site in a situation of copper deficiency. To distinguish between these models and to directly assess the role of FOX1 in iron uptake and the contribution of additional pathways, we sought to test the phenotype of strains containing reduced FOX1.

To generate strains with reduced expression of FOX1, cells of the wild-type Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strain 17D− were transformed with linearized constructs (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) by electroporation (22), allowed to recover for 2 days in liquid TAP (tris-acetate-phosphate) medium under dim light, and then plated on a selective medium (TAP containing 1.5 mM l-tryptophan, 20 μg/ml paromomycin, and 5 μM 5-fluoroindole [5-FI]). The plates were kept in a box constructed with 1/8-in.-thick yellow-2208 acrylic (Polycast Technology, Inc., Stamford, CT) to avoid the degradation of l-tryptophan and 5-FI due to their high sensitivity to light (18). FOX1-silenced cells were selected by using a stepwise increase of 5-FI concentration from 5 μM to 10 μM to 20 μM. Total RNA was prepared and analyzed for the abundance of specific transcripts by real-time PCR as described previously (1, 20). After the reduction of FOX1 transcripts in individual clones was confirmed, they were maintained in selective medium containing 5 μM 5-FI. For all analyses, cells were first cultured in liquid TAP medium without selection for 5 days prior to inoculation into iron-deficient/-limited or copper-deficient TAP medium as described previously (17, 20).

The abundance of the ferroxidase was assessed by immunoblot analysis of whole-cell extracts. Protein samples were generated as described previously (10), with the exception that EDTA (5 mM) was added to the 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer used for resuspending the cells. Electrophoretically separated proteins were transferred at room temperature onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA) with 24 mM Tris base, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol, and 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 150 min under a constant power of 4 W. The membrane was blocked overnight at 4°C with 1% milk in phosphate-buffered saline (9.5 mM phosphate, 148 mM sodium, 11 mM potassium, and 143 mM chloride, pH 7.0) containing 0.3% Tween 20. The primary antibody against ferroxidase was diluted 1:300 in blocking buffer and incubated at room temperature for 90 min. A 1:3,000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit alkaline phosphatase (Southern Biotech) in blocking buffer was used as the secondary antibody for colorimetric detection with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate. The membrane was scanned, and the process repeated with a 1:10,000 dilution of CF1 as the primary antibody. Cells were grown to stationary phase and their metal content was determined as described previously (1) at the Institute for Integrated Research in Materials, Environments, and Society (California State University Long Beach) by using the standard addition method, with the exception that a final concentration of 2.4% nitric acid was used.

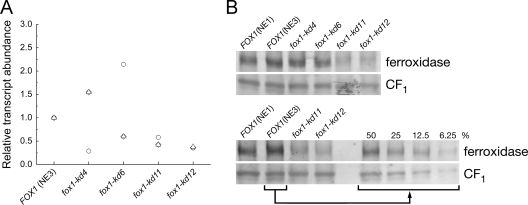

Only a few percent of all transformants subjected to several rounds of selection for knockdown of FOX1 mRNA abundance showed any reduction in transcript abundance, and four of these, fox1-kd4, -kd6, -kd11, and -kd12 (Fig. 1A), were chosen for further analysis. The decrease in FOX1 mRNA was most consistently notable in strains fox1-kd11 and fox1-kd12. This is not unusual, because the degree of knockdown and the ease with which knockdown strains can be obtained appears to be very locus dependent. When we analyzed the abundance of the ferroxidase polypeptide by immunoblot analysis in several experiments, only strains fox1-kd11 and -kd12 showed consistent and notable differences relative to control strains that carried only the empty vector. Strains fox1-kd4 and -kd6 had only slightly reduced amounts of the ferroxidase. By comparison to a dilution series, we could estimate that strains fox1-kd11 and fox1-kd12 had about 12 to 20% of the amount of ferroxidase in equivalent wild-type cells (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of FOX1 mRNA and ferroxidase content in fox1-kd strains. (A) The abundance of FOX1 mRNAs in various strains carrying fox1-kd constructs is shown relative to a strain carrying the empty vector (strain NE3). Cultures were grown in TAP medium containing 20 μM Fe supplementation. Each data point represents the assessment of RNA abundance in an independent culture. (B) The abundance of the ferroxidase in strains grown in TAP medium with 20 μM Fe supplementation was assessed by immunoblot analysis. The abundance of the α and β subunits of CF1, appearing as one band, were visualized as a loading control. (Top) Total protein, equivalent to 1.4 μg of chlorophyll, was loaded on sodium dodecyl sulfate-containing denaturing gels (7.5% acrylamide) in each lane. (Bottom) The amount of ferroxidase in strains fox1-kd11 and fox1-kd12 was assessed by comparison to dilutions of extract from the wild-type strain NE3.

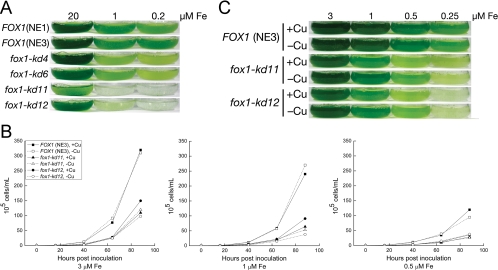

Each strain was tested for growth in media containing various amounts of iron supplementation (Fig. 2). Previously, we had distinguished at least three “stages” of iron nutrition for Chlamydomonas, dependent on the expression of iron assimilation markers and the appearance of visual symptoms of poor iron nutrition (17); 20 μM iron is considered iron replete, 1 to 3 μM iron is considered iron deficient (FOX1 is fully upregulated, but cells are not chlorotic or growth inhibited) and <0.5 μM iron is considered iron limited, because cell division is slowed. We found that the growth of all strains in iron-replete medium was comparable, but all the knockdown strains showed weaker growth in iron-poor medium (Fig. 2A). Strains fox1-kd11 and -kd12 showed the strongest phenotypes, as expected, since they had less FOX1 mRNA and ferroxidase protein than the control strains. We concluded that FOX1 was important for iron uptake in a situation of iron deficiency, while in an iron-replete situation other, presumably lower-affinity, transporters were adequate substitutes. The IRT transporters that belong to the ZIP family of transporters are likely candidates for function in the iron-replete situation.

FIG. 2.

Growth of fox1-kd strains in iron-deficient medium. Each strain (NE1 and NE3 represent wild-type controls carrying only the empty vector) was grown in TAP medium supplemented with the indicated amounts of iron. Growth was assessed by counting cells using a hemocytometer. (A) The flasks were photographed after 96 h of growth postinoculation into medium containing 20, 1, or 0.2 μM Fe. (B) Growth was assessed in iron-poor (3, 1, 0.5, and 0.25 μM Fe) medium with (2 μM; +Cu) or without (−Cu) copper supplementation. The cells were counted in a hemocytometer, and the cultures were photographed (C) after 96 h of growth.

During propagation of the fox1-kd strains, we noticed that one clone was restored to wild-type growth in iron-poor medium (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). When we examined the abundance of the ferroxidase, we noted that the protein was also restored to wild-type levels. This confirms the reduction in FOX1 as being causal for the growth phenotype.

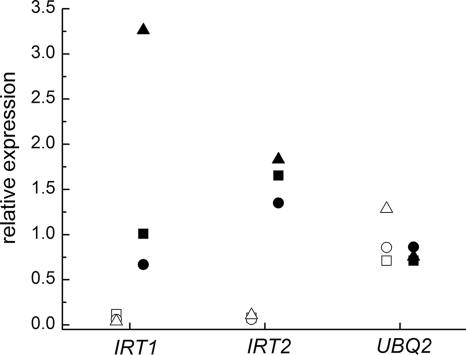

Based on the phenotype of the Chlamydomonas crd2 mutant, which showed a requirement for high-copper nutrition for normal iron assimilation, we had hypothesized that the CRD2 locus either encoded an alternate copper-independent iron assimilation pathway (that functioned only in copper-deficient cells) or that it encoded a factor that facilitated copper loading of the ferroxidase under conditions of copper deficiency (4). For instance, CRD2 might encode a Chlamydomonas homolog of S. cerevisiae Atx1p or Ccc2p (15, 27). To distinguish between these possibilities, we compared the growth of copper-supplemented versus copper-deficient strains fox1-kd11 and -kd12 on iron-poor medium (Fig. 2B and C). If FOX1 function could be covered by another protein in copper-deficient cells, we expected the phenotypes of the knockdowns to be conditional on copper nutrition, by analogy to the plastocyanin and cytochrome c6 situation (16). However, there was no noticeable copper-dependent change in phenotype. Therefore, it seems unlikely that a FOX1-independent pathway would substitute in copper-deficient cells. Rather, the latter hypothesis for CRD2 function is more likely. We noted that the IRT genes are upregulated in conditions of copper deficiency (Fig. 3). IRT1 upregulation at the level of mRNA abundance is dependent on the growth stage of the culture, and therefore, regulation varies between 8- and 80-fold in three independent experiments. IRT2 mRNA abundance is about 20-fold upregulated in conditions of copper deficiency. Nevertheless, this upregulation of IRT mRNA is not sufficient to compensate for the reduction in FOX1 function.

FIG. 3.

IRT expression in copper-deficient Chlamydomonas. RNA was isolated from copper-deficient (filled symbols) or -sufficient (open symbols) wild-type strain 2137 in three independent experiments. The abundance of IRT1 and IRT2 transcripts in each sample relative to their abundance in the mixture of all six samples was estimated by real-time PCR. CβLP was used for normalization. Each data point is the average of technical triplicates and represents one experiment. The regulation for each gene in the three experiments (indicated by square, circle, and triangle, respectively) was as follows: IRT1, 8.3-, 10.8- and 78.4-fold, and IRT2, 20.4-, 21.9-, and 16.9-fold. The UBQ2 gene, whose expression is trace metal nutrition independent, was analyzed in parallel as a control.

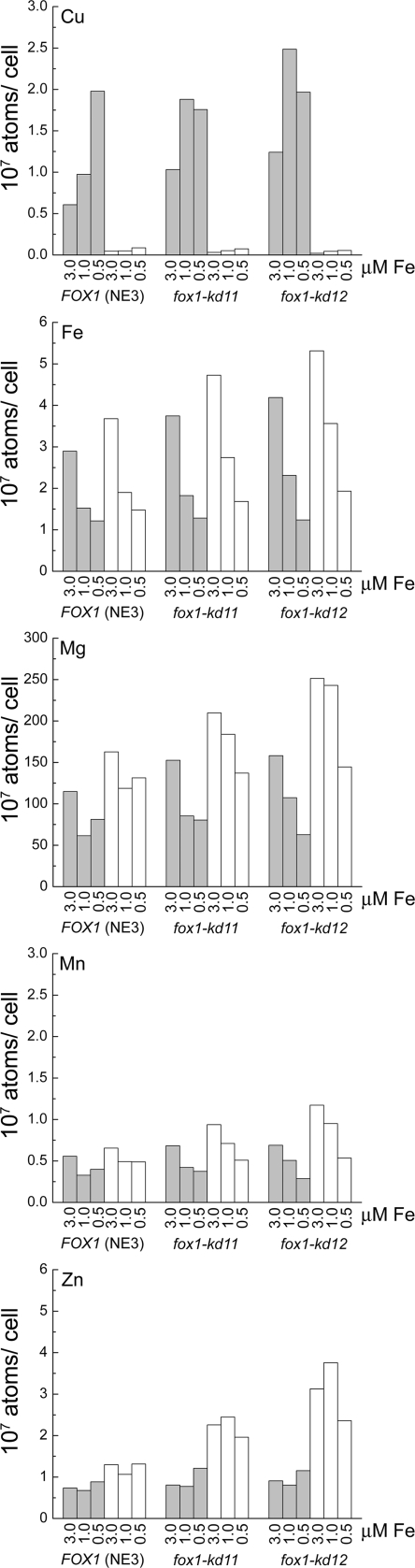

Interestingly, iron-deficient (but not iron-limited) fox1-kd11 and -kd12 strains do eventually reach the same cell density in stationary phase as the wild-type controls (data not shown), and their iron content is indistinguishable from that of the wild type (Fig. 4). This contrasts with the situation of wild-type cells grown in iron-poor medium, which have reduced iron content (17) (Fig. 4). This emphasizes the metabolic distinction between dietary versus genetically determined nutrient deficiencies. In Arabidopsis, the loss of IRT1 function results in chlorosis (25, 26); here, the fox1-kd strains do not get chlorotic. In the former situation, the phenotype is displayed in a different cell (in green organs) from the one (in roots) responsible for assimilation. These physiological distinctions suggest that there might be multiple signal transduction pathways for sensing iron deficiency that assess both external and internal iron supply.

FIG. 4.

Metal content of fox1-kd strains. Cells of each strain were grown in copper-deficient (open bars) or copper-replete (filled bars) TAP medium containing the indicated amounts of iron supplementation. The metal content was measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. The values represent the averages of the results of two independent experiments.

When we compared the metal content of the various strains, we noticed that copper-deficient knockdown strains showed consistently higher zinc content than did the corresponding copper-replete cells or the copper-deficient wild-type strains (Fig. 4). It is possible that the IRT transporters, which probably cannot discriminate between divalent zinc and iron (3, 12), are more greatly engaged in the copper-deficient knockdown strains.

We conclude that there are at least two pathways for iron uptake in Chlamydomonas, one dependent on FOX1 and effective at low concentrations of iron in the medium and other, lower affinity routes, possibly IRT1/2-dependent, that are less metal selective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant GM42143 from the National Institutes of Health. S.I.H. was supported in part by Institutional Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award GM07185.

We thank A. Zed Mason, California State University at Long Beach, for the use of his spectrometer.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 February 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, M. D., J. A. del Campo, J. Kropat, and S. S. Merchant. 2007. FEA1, FEA2, and FRE1, encoding two homologous secreted proteins and a candidate ferrireductase, are expressed coordinately with FOX1 and FTR1 in iron-deficient Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot. Cell 61841-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dancis, A. 1998. Genetic analysis of iron uptake in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Pediatr. 132S24-S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eide, D., M. Broderius, J. Fett, and M. L. Guerinot. 1996. A novel iron-regulated metal transporter from plants identified by functional expression in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 935624-5628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eriksson, M., J. L. Moseley, S. Tottey, J. A. del Campo, J. M. Quinn, Y. Kim, and S. Merchant. 2004. Genetic dissection of nutritional copper signaling in Chlamydomonas distinguishes regulatory and target genes. Genetics 168795-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guerinot, M. L. 2000. The ZIP family of metal transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1465190-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerinot, M. L., and Y. Yi. 1994. Iron: nutritious, noxious, and not readily available. Plant Physiol. 104815-820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hellman, N. E., and J. D. Gitlin. 2002. Ceruloplasmin metabolism and function. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 22439-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herbik, A., C. Bolling, and T. J. Buckhout. 2002. The involvement of a multicopper oxidase in iron uptake by the green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 1302039-2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbik, A., S. Haebel, and T. J. Buckhout. 2002. Is a ferroxidase involved in the high-affinity iron uptake in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii? Plant Soil 2411-9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howe, G., and S. Merchant. 1992. The biosynthesis of membrane and soluble plastidic c-type cytochromes of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is dependent on multiple common gene products. EMBO J. 112789-2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan, J., and T. V. O'Halloran. 1996. Iron metabolism in eukaryotes: Mars and Venus at it again. Science 2711510-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korshunova, Y. O., D. Eide, W. G. Clark, M. L. Guerinot, and H. B. Pakrasi. 1999. The IRT1 protein from Arabidopsis thaliana is a metal transporter with a broad substrate range. Plant Mol. Biol. 4037-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kosman, D. J. 2003. Molecular mechanisms of iron uptake in fungi. Mol. Microbiol. 471185-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.La Fontaine, S., J. M. Quinn, S. S. Nakamoto, M. D. Page, V. Göhre, J. L. Moseley, J. Kropat, and S. Merchant. 2002. Copper-dependent iron assimilation pathway in the model photosynthetic eukaryote Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot. Cell 1736-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin, S.-J., R. A. Pufahl, A. Dancis, T. V. O’ Halloran, and V. C. Culotta. 1997. A role for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATX1 gene in copper trafficking and iron transport. J. Biol. Chem. 2729215-9220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merchant, S., and L. Bogorad. 1987. Metal ion regulated gene expression: use of a plastocyanin-less mutant of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii to study the Cu(II)-dependent expression of cytochrome c-552. EMBO J. 62531-2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moseley, J. L., T. Allinger, S. Herzog, P. Hoerth, E. Wehinger, S. Merchant, and M. Hippler. 2002. Adaptation to Fe-deficiency requires remodeling of the photosynthetic apparatus. EMBO J. 216709-6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palombella, A. L., and S. K. Dutcher. 1998. Identification of the gene encoding the tryptophan synthase β-subunit from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 117455-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Philpott, C. C. 2006. Iron uptake in fungi: a system for every source. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763636-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quinn, J. M., and S. Merchant. 1998. Copper-responsive gene expression during adaptation to copper deficiency. Methods Enzymol. 297263-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson, N. J., C. M. Procter, E. L. Connolly, and M. L. Guerinot. 1999. A ferric-chelate reductase for iron uptake from soils. Nature 397694-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimogawara, K., S. Fujiwara, A. Grossman, and H. Usuda. 1998. High-efficiency transformation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by electroporation. Genetics 1481821-1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stearman, R., D. S. Yuan, Y. Yamaguchi-Iwai, R. D. Klausner, and A. Dancis. 1996. A permease-oxidase complex involved in high-affinity iron uptake in yeast. Science 2711552-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoj, C. S., and D. J. Kosman. 2005. Copper proteins: oxidases, p. 1134-1159. In R. B. King (ed.), Encyclopedia of inorganic chemistry. Wiley, New York, NY.

- 25.Varotto, C., D. Maiwald, P. Pesaresi, P. Jahns, F. Salamini, and D. Leister. 2002. The metal ion transporter IRT1 is necessary for iron homeostasis and efficient photosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 31589-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vert, G., N. Grotz, F. Dédaldéchamp, F. Gaymard, M. L. Guerinot, J. F. Briat, and C. Curie. 2002. IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell 141223-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan, D. S., R. Stearman, A. Dancis, T. Dunn, T. Beeler, and R. D. Klausner. 1995. The Menkes/Wilson disease gene homologue in yeast provides copper to a ceruloplasmin-like oxidase required for iron uptake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 922632-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.