Abstract

This study compares condom use reported two ways. 251 heterosexual participants (63% female) reported condom use on a prospective daily diary and on a retrospective questionnaire. Proportion of condom use with vaginal sex was calculated from the diary data and contrasted with retrospective categories. Responses were consistent for some participants, especially those who used condoms never or always, but responses from others show considerable variability. Participants with few sexual encounters were more likely than those with more encounters to use “never” and “every time” endpoints. The results call into question the way participants interpret the meaning of retrospective categories.

Keywords: condom use, retrospective questionnaires, daily diary

Introduction

Condoms provide substantial protection from the sexual transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Valid and reliable measures of condom use are needed to adequately measure condom use and to determine the success of risk reduction interventions (Weir, Roddy, Zekeng, & Ryan, 1999). To this end, retrospective self-report surveys have been used widely to collect information about sexual behavior, including condom use. However, self-report data on condom use may be biased (Zenilman et al., 1995), and little is known about how people interpret and respond to retrospective questions about condom use. Given that there is no agreed-upon best approach for measuring condom use, the validity and reliability of condom use reports collected via retrospective survey are uncertain.

The prospective daily diary is gaining favor as the closest approximation to a “gold standard” that is available for assessing the validity and reliability of sexual behavior measurement, including condom use (Graham, Catania, Brand, Duong, & Canchola, 2003; Schroder, Carey, & Vanable, 2003). Researchers have compared diary vs. retrospective reports, with inconsistent findings possibly due to differences between subject populations and the behaviors measured. A recent review (Schroder et al., 2003) concluded that existing studies show no clear trend toward under- or overreporting of sexual behavior on questionnaires, relative to diaries, and that variations in item content and the samples studied (adolescents, sex workers, college students, gay men) might affect general tendencies to overreport or underreport.

Questions that incorporate categorical answers (for example, “less than half the time,” “almost all the time,” etc.) are common for assessing condom use (Sheeran & Abraham, 1994). However, different participants may hold different interpretations of the meanings of the categories (Catania, Gibson, Chitwood, & Coates, 1990), and there may not be a sufficient number of categories to capture the information accurately (Jaccard, Wan, Dittus, & Quinlan, 2002). Fortenberry, Cecil, Zimet, and Orr (1997) examined the agreement of diaries and retrospectively collected self-reported condom use in a sample of adolescent women. The measure of condom use on the retrospective questionnaire incorporated the categories never, less than half the time, about half the time, more than half the time, and always. Although the diary and retrospective questionnaire displayed the expected linear relationship, approximately 20% of the reports were not in close agreement and called into question the assumption that of “all of the time” truly means with every act of intercourse.

This issue was also explored in a study in which participants were asked to match the categories never, rarely, sometimes, most of the time, and always to descriptions of a hypothetical couple’s condom use (Cecil & Zimet, 1998). A third of the participants described using a condom one out of 20 times as “never,” and a quarter equated two out of 20 times with “never.” Forty percent described using a condom 19 out of 20 times as “always,” and 23% said that 18 out of 20 times was “always.” The variability in these descriptions was most apparent for categories in the middle of the two extremes of never and always. Although the overall pattern of responses generally confirmed the validity of the response categories, there was sufficient variation in responses to bring into question both the meaning of these categories and the practice of collapsing them into dichotomies such as always versus not always.

Using data from an 8-week daily diary of sexual behavior and condom use, in this paper we describe variability in reports of condom use. We compare reported condom use from the diary with condom use reported by the same adolescent and adult heterosexual participants in a retrospective questionnaire administered after the diary collection was complete. By comparing the two kinds of measures, we can examine some of the ways in which retrospective, categorical reports may fail to capture these health-related behaviors.

Methods

Participants

The data come from a larger study of substance use and unprotected sex (Gillmore et al., 2002; Morrison et al., 2003). Participants included college students, adults visiting an STD clinic, and adolescents (see Gillmore et al., 2002; Morrison et al., 2003 for further details). College students were randomly sampled from student registration records at a large northwestern university. Mailed letters invited the students to participate in a study of health habits, including alcohol use and sexual activity. Students who responded to the letter were screened for eligibility (see below for criteria). Sexually experienced adolescents between the ages of 13 and 19 were recruited through flyers posted in locations that teenagers frequent (e.g., recreation centers) and distributed by clinicians in teen health clinics. For the adult sample, recruitment fliers were placed in the restrooms and waiting rooms of several public health clinics treating people with STDs. The posted fliers included tear-off coupons containing local and toll free telephone numbers for potential participants to call. To supplement this passive procedure in the largest clinic, a member of the project staff was located in a private area near the clinic to tell potential participants about the project and be available to answer questions. Clients in both the teen and STD clinics could also drop a card with their name and contact information into a sealed box located in the clinic.

Eligible persons were unmarried, had engaged in heterosexual sex at least four times in the prior 2 months, were not in a current monogamous relationship of more than 6 months duration, had used condoms at least once in the last year, and had drunk alcohol at least 4 times in the last 2 months (the latter two requirements were necessary for the purposes of the larger study).

Procedure

The study was described as a “health habits” study examining daily patterns of various health-related behaviors. Participants were randomly assigned to fill out written daily diaries and return them by mail or to participate in daily telephone interviews, and were then mailed an initial entry questionnaire to obtain background information. Daily data collection (either written or by telephone) began when the entry questionnaire was returned. Participants in the telephone condition responded to a daily telephone interview to collect diary information. Each received a copy of the daily survey form, which was identical to that used by those in the diary condition, to follow as the interviewer asked the questions. At the conclusion of each interview, an appointment was made for the next day’s interview. Participants in the self-administered written diary condition were sent weekly packets containing instructions, seven daily diary forms and seven self-addressed, stamped envelopes in which to mail back each day’s diary. Research staff telephoned participants in the written diary condition weekly to offer encouragement and. provide an equivalent opportunity to get clarification about any items or ask any questions. The diary (identical in the telephone and self-administered conditions) included a checklist of questions about smoking, diet, dental care, exercise, seatbelt use, sleeping patterns, drug and alcohol use, and sexual behaviors. On the first day of daily data collection (for both collection methods), participants reported on their activities in the past 24 hours. Each day thereafter, respondents were asked “Since you filled out this form [talked with us] yesterday, did you …”

Following the 8 weeks of daily data collection, all participants were mailed a self-administered retrospective questionnaire to complete and return that asked about several of the behaviors listed on the diaries. They were randomly assigned to recall their behavior over the past week, past month (28 days), or past two months (56 days).

Participants were each paid $15 for the entry survey, then weekly for the daily diaries ($2 for each daily report, a $3 bonus for each week with no missing days), and $10 for the exit survey. All procedures were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Up to three occasions of sexual intercourse could be recorded in each day’s diary. For each occasion of sexual intercourse reported, participants were asked a series of questions including whether intercourse was vaginal, anal, or oral and whether a condom was used for each type of sexual behavior. For these analyses, only reports of vaginal sex were used; the proportion of vaginal sex occasions in which condoms were used was calculated.

The self-administered retrospective questionnaires asked, “In the past (week/month/2 months) how often were condoms used when you had vaginal sex?” Responses were recorded on a 7-point ordinal scale with responses from never to every time.

Data analysis

We compared the proportion of condom use calculated from the diary to responses on the retrospective questionnaire, and we also assessed this correspondence for (1) participants having lower and higher numbers of sexual encounters over the eight weeks of daily data collection (fewer than 5 and 5 or more), (2) type of participant (adolescent, college student, adult), (3) gender, (4) retrospective reporting period (1 week, 4 week, 8 week), (5) reporting condition (telephone vs. mail), and (6) whether participants’ retrospective reports over-, under-, or consistently matched their diary reports. For the latter, consistency of reporting was determined by categorizing diary proportions as follows: Never: 0%; Rarely: <25%; Less than half the time: 25% to <40%; About half the time: 40% to <60%; More than half the time: 60% to <75%; Almost always: 75–99%; Every time: 100%.

Results

Of 382 participants who completed the exit survey, 187 completed all 56 days of reporting, and 88% had fewer than 10 missing days. The mean number of missing days was 3.3 (2.9 in the written condition and 3.6 in the telephone condition (F(1,380)=1.64, ns).

Data from 251 participants (157 female) who had engaged in vaginal sex during the diary period and completed the retrospective survey were analyzed. About one third (36%, n = 91) of this sample were university students, 107 (43%) were STD clinic clients, and 53 (21%) were adolescents. Age for the combined sample ranged from 14 to 35 (mean 22.3; median 21). Participants were largely Caucasian (70%), but also included African American (8%), Asian American (9%), Latino (6%), and mixed ethnicity or other participants (7%).

Number of occasions of sexual intercourse reported for the eight weeks ranged from 1 to 85 per participant (mean=14.3, SD=12.6, median=11), and 45% of encounters were condom-protected. There were no differences in rates of behaviors reported by those in the telephone (n=127) and written diary (n=124) conditions (Gillmore et al., 2001).

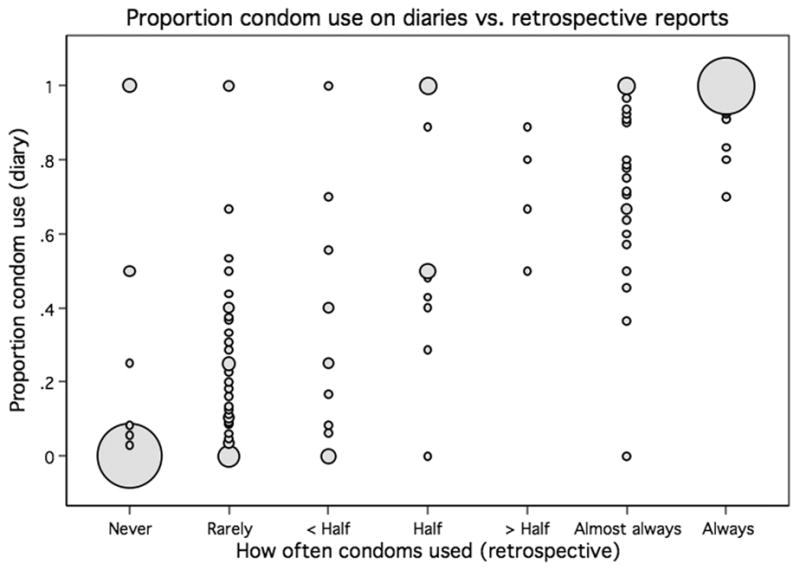

Figure 1 plots, for each participant, the response category chosen on the retrospective questionnaire against the mean proportion of condom use calculated from the diary data for the time period specified in the 3 recall conditions (one week [n=54], one month [n=95], and 2 months [n=102]).1 In this figure, the size of the plot point (circle) is proportional to the number of people who gave that set of responses. As shown in the figure, the largest concentration of perfectly consistent answers occurs among participants who used condoms “never” or “always” (lower left and upper right corners of the figure, n=76 and 59 respectively). This pattern is unsurprising given the relative ease of reporting accurately about a consistent habit. The polyserial correlation of .85 is largely driven by this clustering. Otherwise, the variability in agreement is striking: for example, among participants who stated retrospectively that they “almost always” used condoms, condom use as measured by the daily diary ranged from 0 to 100%.

Figure 1. Proportion of condom use reported on daily diaries vs. retrospective report.

Note. Size of points reflects number of participants represented at those coordinates.

The distribution of responses on the retrospective questionnaire differed by the frequency with which the participants had sex: participants (n=104) who reported having fewer than 5 sexual encounters during the two-month data collection period (as reported by diary) were more likely to concentrate their responses in the endpoints of the scale, compared to participants who had 5 or more sexual encounters (n=147). While 73% of the former group used the endpoints of the scale (always or never), the latter group used more of the scale, with 52% percent using the endpoints.

We assessed the correspondence of diary and retrospective reports by classifying participants as consistently reporting on both measures, over-reporting on the retrospective questionnaire relative to the diary, or underreporting. In the full sample, 73% were consistent reporters, with 15% overreporting and 12% underreporting condom use on the retrospective questionnaire. Almost 75% of the consistent reporters used condoms either “always” or “never.” College students displayed the most consistency, with 82% being consistent reporters compared to 64% of teenagers and 69% of adult STD clinic clients. Teenagers and college students were more likely to be overreporters than underreporters (24% and 11% for teenagers; 12% and 6% for college students); most of the inconsistency was due to using condoms 100% of the time as reported by diary, but choosing a response alternative other than “always” on the retrospective questionnaire. Consistency did not vary by gender or reporting period, but participants in the daily telephone collection condition were more likely than those in the daily written collection condition to be underreporters (16%) rather than overreporters (6%), a finding not evident in the written condition.

Discussion

We examined data from participants who filled out both daily diaries and retrospective reports of condom use and other behavior. The findings support others’ suggestions that participants vary in their interpretation of proportional categories of condom use (never, rarely, always, etc.) (Cecil & Zimet, 1998; Jaccard et al., 2002). Although proportional categories bore a general ordinal relationship to actual proportions of condom use calculated from daily reports, there was much variability in this agreement. For some participants, “never” using condoms did not mean 0% of the time, and “always” did not mean using condoms every time. Considering our results in conjunction with the findings of Cecil and Zimet (1998), it appears that people may view “never” and “always” not as absolute but as a range of behavior with exceptions.

Although these categories are meant to measure a proportional estimate—the proportion of intercourse occasions in which condoms were used—in practice they seem to be abstractions of proportions with no strict definition, and as such are subject to individual interpretation. One way to improve retrospective survey questions might be to add additional information to further describe or define response categories. Cecil and Zimet (1998) suggest adding additional verbal clarification to categories so that for example, “always means that a condom was used every time a person had intercourse, with no exceptions.” Another approach, used by Jaccard et al. (2002), is to incorporate percentile ranges with verbal categories to further describe response categories. Some of the observed consistency between daily reports and retrospective questionnaires may be due not to a good memory but simply to the existence of a regular pattern or habit. People who always or never use condoms may report this behavior consistently, both daily and after the fact. With sexual behavior, such habits may be the result of personal behavioral rules, such as always using condoms. Such rules would tend toward the extreme ends of a frequency distribution: that is, rarely would a person have a rule about using a condom “about half the time.” Moreover, summary questions are likely to be constructed not by counting discrete events but by using some kind of inference rule (Armstrong, White, & Saracci, 1992; Schwarz, 1990). These summary questions may elicit modal behavior rather than a true accounting of behavior over the relevant time period.

The existence of such rules may help explain our findings that participants who had more sexual encounters used intermediate scale categories more than did participants with fewer sexual encounters. People with more sexual encounters have more opportunity to deviate from rules or habits. A person who has sex twice and uses condoms both times is more consistent than a person who has sex 20 times and uses a condom 19 times, but the latter person has more occasions on which the rule could potentially be broken.

In this study, the diary period was the same as the period covered by the retrospective questionnaire. Completion of the diary may have enhanced memory for the relevant behaviors, leading to stronger correlations of diary and retrospective measures than would be obtained without prior diary assessment. Studies that have compared correlations of diary measures to retrospective questionnaires administered before and after the diary period have suggested that the magnitude of this over-agreement is small (see for example Giovanucci et al., 1991; Pietinen et al., 1998), and studies of accuracy in recall have shown that diary-keeping does not facilitate more accurate recall (Stone et al., 2003; Thomas & Diener, 1990). In interpreting the results of the present study, it is prudent to consider the agreement of diary and retrospective measures as an upper bound.

Our findings are limited to condom use with vaginal sex among heterosexuals. In addition, some of the participants had few sexual encounters from which to calculate proportion of condom use, and the resulting estimates could be unstable. Additional qualitative studies would be of interest to better understand how these categories are used and the meaning behind the use of various categories.

As discussed above, there is a great deal of variability among people as they try to fit their behavior into categories, and this variability affects the psychometric properties of the measures (Jaccard et al., 2002). Furthermore, biases in these measures can affect estimates of the association of behaviors to outcomes. Given that departures from ordinality of rating scales or frequency categories has important implications, diary reports can help identify these departures and illuminate potential sources of error in the more commonly-used, and easier to implement, retrospective measures of behavior.

Acknowledgments

Supported by AA013688, AA000183 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

Mary Gillmore is now at the School of Social Work, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ

There were equal numbers of participants in the three recall conditions. Fewer participants in the one-week condition appear in this analysis because many had not had sex in the one week previous to completing the retrospective questionnaire.

References

- Armstrong BK, White E, Saracci R. Principles of exposure measurement in epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Gibson DR, Chitwood DD, Coates TJ. Methodological problems in AIDS behavioral research: Influences on measurement error and participation bias in studies of sexual behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:339–362. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecil H, Zimet GD. Meaning assigned by undergraduates to frequency statements of condom use. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1998;27(5):493–505. doi: 10.1023/a:1018756614107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore MR, et al. Daily data collection of sexual and other health-related behaviors. Journal of Sex Research. 2001;38(1):35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore MR, et al. Does “high=high risk”? An event-based analysis of the relationship between substance use and unprotected anal sex among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6(4):361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Giovanucci E, et al. The assessment of alcohol consumption by a simple self-administered questionnaire. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1991;133:810–817. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham CA, Catania J, Brand R, Duong T, Canchola J. Recalling sexual behavior: A methodological analysis of memory recall bias via interview using the diary as the gold standard. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40(4):325–332. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Wan CK, Dittus P, Quinlan S. The accuracy of self-reports of condom use and sexual behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32(9):1863–1905. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DM, et al. Adolescent drinking and sex: Findings from a daily diary study. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35(4):162–168. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.162.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietinen P, et al. Reproducibility and validity of dietary assessment instruments. I. A self-administered food use questionnaire with a portion size picture booklet. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1988;128:655–666. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder KEE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(2):104–123. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N. Assessing frequency reports of mundane behaviors: Contributions of cognitive psychology to questionnaire construction. In: Hendrick C, Clark MS, editors. Research methods in personality and social psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. pp. 98–119. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, Abraham C. Measurement of condom use in 72 studies of HIV-preventive behaviour: a critical review. Patient Education and Counseling. 1994;24:199–216. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(94)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, et al. Intensive momentary reporting of pain with an electronic diary: reactivity, compliance, and patient satisfaction. Pain. 2003;104(1–2):343–351. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DL, Diener E. Memory accuracy in the recall of emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:291–297. [Google Scholar]

- Weir SS, Roddy RE, Zekeng L, Ryan KA. Association between condom use and HIV infection: a randomised study of self reported condom use measures. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1999;53(7):417–422. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.7.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenilman JM, et al. Condom use to prevent incident STDs: the validity of self-reported condom use. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1995;22(1):15–21. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]