Abstract

The main challenge of gene therapy is to provide long-term, efficient transgene expression. Long-term transgene expression from first generation adenoviral vectors (Advs) delivered to the central nervous system (CNS) is elicited in animals not previously exposed to adenovirus (Ad). However, upon systemic immunization against Ad, transgene expression from a first generation Adv is abolished. High-capacity Advs (HC-Advs) provide sustained very long-term transgene expression in the brain, even in animals pre-immunized against Ad. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that a HC-Adv in the brain would allow for long-term transgene expression, for up to 1 year, in the brain of mice immunized against Ad prior to delivery of the vector to the striatum. In naïve animals, the expression of β-galactosidase from Adv or HC-Adv was sustained for 1 year. In animals immunized prior to vector delivery, expression from a first generation Adv was abolished. These results point to a very long-term HC-Adv-mediated transgene expression in the brain, even in animals that had been immunized systemically against Ad before the delivery of HC-Adv into the brain. This study therefore indicates the utility of HC-Adv as a powerful gene therapy vector for chronic neurological disorders, even in patients who had been pre-exposed to Ad prior to gene therapy.

INTRODUCTION

First generation adenoviral vectors (Advs) are excellent gene transfer vehicles for implementing gene therapy approaches in neurological diseases. Their efficacy in experimental disease models has led to several clinical trials.1,2 The most common first generation Advs developed for gene therapy are based on Ad2 and Ad5 serotypes. The wild-type adenovirus (Ad) genome encodes five early transcription units, E1A, E1B, E2, E3, and E4, whose products regulate viral DNA replication, expression of late genes and viral packaging. Recombinant Ad are made replication-defective through deletions in the E1 region, into which the therapeutic transcriptional cassette is inserted. Thus, replication defective Advs maintain up to 90% of the wild-type Ad genome. These wild-type transcription units can be expressed at low levels, providing antigenic proteins that can be the potential targets of an activated anti-Ad immune response.

Adv-mediated transgene expression in the central nervous system (CNS) is sustained and long-term in animals not exposed to Ad. Although initially naïve animals injected with Advs into the brain parenchyma will develop a dose-dependent innate, local immune response, it subsides rapidly and does not compromise long-term transgene expression.3,4 However, systemic immunization against Ad curtails transgene expression from first generation Adv.5 Immunization against Ad following the intracranial injection of Adv results in the infiltration of T cells into the brain parenchyma clearing partially or totally virally transduced cells.5–7 Most likely the immune system targets antigenic epitopes from viral proteins expressed from the remaining portions of the wild-type Ad genome within these first generation vectors.

Long-term, safe, and efficacious gene transfer is central to therapeutic gene therapy since a majority of the human population has been exposed to Ad during childhood. For this reason, helper-dependent Ads (also known as high-capacity, “gutless” vectors; HC-Ads) have been engineered; these are devoid of all viral coding sequences.8–10 HC-Ads only contain minimal portions of the Ad genome; these are limited to cis-acting elements for viral DNA replication and packaging, i.e., the inverted terminal repeat (ITR) sequences and packaging signal. Since these elements are of restricted size, helper-dependent vectors have the capacity to carry up to ~36 kilobase of foreign DNA. The development of HC-Ad has permitted the efficient and sustained transduction of the brain even in the presence of systemic anti-Ad immune responses; so far, however, studies on long-term expression in animals systemically immunized against Ad before gene transfer, have been limited to only 2 months in Sprague–Dawley rats.6 Thus, it is important to determine the long-term fate of transgene expression from HC-Ad in the brain of animals previously exposed to Ad immunization, which, so far, remains unknown.11

In the present study, we demonstrate that transgene expression from HC-Ad is indeed sustained for up to 1 year, following the injection of these vectors into the brain of mice systemically immunized against Ad (before viral vector delivery to the brain). In addition, direct immunization with HC-Ad induces a cellular, but not humoral immune response; intriguingly, this immune response is unable to eliminate transgene expression from a first generation Adv injected into the brain. Thus, HC-Advs provide sustained long-term transgene expression in the CNS even in animals previously exposed to Ad, and induce a lower immune response when compared to first generation Ad. This immunological profile highlights the advantages of the HC-Ad system for the potential treatment of chronic neurological disease.

RESULTS

Brain cell types expressing vector-encoded transgenes

To characterize the cell types expressing vector-encoded transgenes 14 days following the injection of 1 × 107 infectious units (iu) of vector into the naive mouse brain, we double labeled transgene expressing cells with various cell type-specific markers using immunocytochemistry. Immunofluorescence for β-galactosidase combined with microtubule-associated protein-2 (for neurons), glial fibrillary acidic protein (for astrocytes), myelin basic protein (for oligodendrocytes), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (nuclear counterstain), was performed on brain sections of mice injected with Ad-mCMV-βgal (expressing β-galactosidase); this demonstrated that β-galactosidase is expressed in astrocytes (glial fibrillary acidic protein positive cells; 97%), occasional oligodendrocytes (not illustrated) (<1%), but not in neurons (microtubule-associated protein-2 positive cells; 0%) (Figure 1). However, brains of animals injected with HC-Ad (HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE) show expression of the transgene β-galactosidase in astrocytes (70%), and neurons (26%), but only in occasional oligodendrocytes (<1%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. β-galactosidase (β-gal) expression in neurons and astrocytes in non-immunized brains infected with adenovirus (Ad) (HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE).

Panel (a) illustrates confocal images of immunohistochemistry for β-gal combined with the astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (top row) or microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP-2) (marker for neurons) (second row) of mouse brain sections injected in the striatum with Ad-mCMV-βgal. The top row shows merged images illustrating the co-localization of β-gal and GFAP, thus confirming the expression of transgene in astrocytes (97%). The second row of images shows staining for β-gal combined with MAP-2. In the merged image no co-localization is observed demonstrating that β-gal is not expressed in neurons in mouse brains injected with Ad-mCMV-βgal (0%). Panel (b) shows confocal images of immunofluorescence for β-gal combined with GFAP (marker for astrocytes) (top row) or MAP-2 (marker for neurons) (second row) of sections of mouse brain injected in the striatum with HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE. The top row shows staining for β-gal combined with GFAP. In the merged image note the co-localization of β-gal and GFAP verifying the expression of transgene in astrocytes (70%). The second row of images show staining for β-gal combined with MAP-2. The merged image shows co-localization of β-gal with MAP-2 demonstrating that the transgene is expressed in neurons in the brain of mice injected with HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE (26%). Scale bar: 30 μm. mCMV, murine cytomegalovirus; WPRE, wood chuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element.

Long-term transgene expression from Ad injected into the mouse striatum of pre-immunized animals

We determined whether long-term transgene expression can be achieved following intracranial injection of HC-Ad, or first generation Ad, into the brain of animals that had been immunized systemically by intraperitoneal injection against Ad (preceding the injection of vectors into the brain), and compared this to naïve animals. Transgene expression was sustained up to 1 year after injection in naïve animals injected into the striatum with either vector (Figure 2). However, animals previously immunized against a first generation Ad, Ad-hCMV-HPRT, had a highly significant reduction in vector-mediated transgene expression (F= 57.08, df = 1, P < 0.001; two-way analysis of variance) already clearly evident 14 days after the intracranial injection (Figure 2). In animals injected with HC-Ad, however, there was no significant difference in transgene expression between immunized and non-immunized animals (F = 3.36, df = 1, P = 0.07; two-way analysis of variance) and expression levels were maintained for 1 year post-vector injection into the brain (Figure 2) (F = 1.2, df = 5, P = 0.33; two-way analysis of variance).

Figure 2. Long-term transgene expression following the injection of adenovirus (Ad) into naïve mice, or mice immunized against Ad preceding the delivery of vectors into the brain.

Panel (a) shows mouse brain sections injected with Ad-mCMV-βgal immunostained for β-galactosidase (β-gal) in naïve animals (top row), or animals preimmunized against Ad (second row) at different time points. Naïve animals show a robust expression of transgene even 1 year after the intrastriatal injection. However, preimmunized animals show a significant decrease of transgene expression 14 days after injection and finally loss of the transgene expression. Panel (b) shows the expression of β-gal in brain sections of mice injected with High-capacity Ad (HC-Ad) (HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE). Both naïve and preimmunized animals show sustained expression of the transgene even 1 year after vector injection into the brain. Scale bar: 1 mm. (c,d) shows the stereological quantification of β-gal expressing cells in animals injected with Ad-mCMV-βgal or HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE. The quantitative analysis demonstrates that the expression of the transgene is sustained following HC-Ad injection 1 year after the injection even in animals that have been pre-immunized against Adv. c shows the stereological estimation of the total number of β-gal expressing cells in mouse striatum 14, 30, 60, 90, 180, and 365 days after intracranial (IC) injection of Ad-mCMV-βgal in naïve and preimmunized animals. Note that naïve animals show sustained transgene expression that decreases slightly over 1 year. However preimmunized animals show a significant decrease of transgene expression 14 and 30 days after IC injection, and it is almost completely lost at 180 days [(F = 57.08, df = 1, P < 0.001; two way analysis of variance (ANOVA)]. d shows the stereological estimation of the total number of β-gal expressing cells in mouse striatum 14, 30, 60, 90, 180, and 365 days following the IC injection of HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE in naïve and preimmunized animals. Naïve and preimmunized animals illustrate sustained transgene expression over 1 year. There was no significant difference in transgene expression between immunized and non-immunized animals (F = 3.36, df = 1, P = 0.07; two way ANOVA) and expression levels were maintained for 1 year post-vector injection into the brain (Figure 2) (F = 1.2, df = 5, P = 0.33; two way ANOVA). IP, intraperitoneal; mCMV, murine cytomegalovirus; WPRE, wood chuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element.

To control for systemic immunization we measured the increase in the serum titer of neutralizing anti-Ad antibodies; in addition to determining whether the injection of either vector into the brain could influence serum anti-Ad titers, we determined the neutralizing antibody titer over time, following the injection of either vector into the brain. A robust titer of neutralizing antibodies against Ad was detected for up to 60 days in all immunized animals, decreasing at 90 days, and becoming very low or absent at later times (Figure 3). Importantly, serum titers of neutralizing antibodies were unaffected by the intracranial delivery of either vector, indicating that careful delivery of vectors into the brain parenchyma does not alter the nature of the systemic immune response.

Figure 3. Anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibody titers in animals injected with Ad into the brain.

Titer of neutralizing antibodies against Ad in serum of animals injected either with Ad-mCMV-βgal (a) or HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE (b) in the striatum of animals immunized against Ad (Ad-hCMV-HPRT), a month earlier. Sera were analyzed 14, 30, 60, 90, 180, and 365 days after the intracranial (IC) delivery of vectors. As expected, immunization with Ad-hCMV-HPRT induced a high titer neutralizing antibody response evidenced by approximately 1:200 titer 60 days after the IC injection. Very low titers were found 90 days post injection, which become very low or absent after 180 days. Note that naïve animals (sham-immunized) do not show any neutralizing antibodies against Ad. There were no differences in the serum antibody titers of animals injected into the brain with either vector. Ad, adenovirus; hCMV, human cytomegalovirus; HPRT, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; IP, intraperitoneal; mCMV, murine cytomegalovirus; WPRE, wood chuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element.

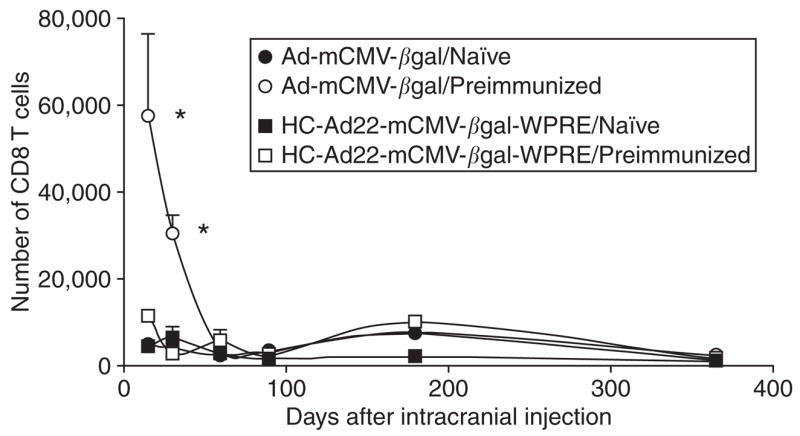

The number of CD8+ T cells in the striatum was quantified. A significant increase of CD8+ T cells was found in the striatum of pre-immunized animals injected intracranially with Ad-mCMV-βgal. The number of CD8+ T cells decreased by 90 days after the intracranial injection of vector, a time when transgene expression had almost been completely eliminated. No significant increase of CD8+ T cells was found in the striatum of pre-immunized animals injected with HC-Ad (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Infiltration of CD8+ T cells following the delivery of adenovirus (Ad) into the brain of immunized mice.

This graph illustrates the unbiased stereological quantification of CD8+ T cells that infiltrated the striatum of mice preimmunized with Ad-hCMV-HPRT, following the intracranial injection of either Ad-mCMV-βgal or high capacity-Ad (HC-Ad). Preimmunized animals injected intracranially with HC-Ad do not show any statistically significant increase of CD8+ T cells in the striatum. However, preimmunized animals injected intracranially with Ad-mCMV-βgal show a dramatic increase in the number of CD8+ T cells in the striatum 14 and 30 days after the intracranial injection. *P < 0.05 with respect to naïve animals and preimmunized animals injected with HC-Adv. hCMV, human cytomegalovirus; HPRT, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; mCMV, murine cytomegalovirus; WPRE, wood chuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element.

Systemic immunization with HC-Ad elicits T-cell responses but not neutralizing antibodies

In order to test whether systemic immunization with HC-Ad is able induce a systemic immune response capable of eliminating transgene expression mediated by first generation Advs previously injected into the brain, animals were injected systemically with the control vector HC-Ad22-mCMV-TKnull-WPRE; results were compared to those obtained in another group of animals that were immunized with Ad-hCMV-HPRT, or saline alone. Mice were thus injected into the brain with Ad-mCMV-βgal, and 30 days later they were immunized systemically with either Ad-hCMV-HPRT or HC-Ad22-mCMV-TKnull-WPRE. Animals injected with Ad-hCMV-HPRT display an important increase in serum titers of anti-Adv antibodies (Figure 5a), and a corresponding loss of transgene expression from the striatum (Figure 5b). However, animals immunized with HC-Ad22-mCMV-TKnull-WPRE did neither demonstrate an increase in antibody titers, nor a loss in transgene expression. This demonstrates that HC-Ads are unable to induce a systemic anti-Ad immune response that is able to eliminate transgene expression from the brain (Figure 5b).

Figure 5. High capacity-adenovirus (HC-Ad) is not able to prime a systemic anti-Ad immune response.

(a) shows the serum neutralizing antibody titers against Ad of animals injected with Ad-mCMV-βgal in the striatum and immunized 30 days later, with either Ad (Ad-hCMV-HPRT) or HC-Ad22-mCMV-TKnull-WPRE; brains and sera were analyzed 30 and 60 days after immunization. Note that Ad-hCMV-HPRT immunization is able to generate a high neutralizing antibody response in comparison with the very low or absent titer induced by HC-Ad immunization. Control naïve animals (injected with saline) did not show any neutralizing antibodies against Ad. (b) shows the number of β-galactosidase (β-gal) expressing cells in the striatum of mice injected with Ad-mCMV-βgal in naïve animals (injected with saline; sham immunized), animals immunized with Ad (Ad-hCMV-HPRT), or animals immunized with HC-Ad22-mCMV-TKnull-WPRE. Animals immunized with Ad-hCMV-HPRT show an increase in the serum antibody titer, and a corresponding decrease in the number of β-gal expressing cells. However, animals immunized with HC-Ad show no statistical differences compared to the naïve animals. *P < 0.05 compare to saline. hCMV, human cytomegalovirus; HPRT, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; IC, intracranial; IP, intraperitoneal; mCMV, murine cytomegalovirus; TK, thymidine kinase; WPRE, wood chuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element.

To confirm the lack of a systemic immune response to HC-Ad we performed two additional experiments to assess the capacity of HC-Ad to induce either humoral or cell-mediated immune responses. In the experiment depicted in Figure 6a, we quantified antibody responses against two HC-Ads. In this experiment mice were injected into the brain with Ad-mCMV-βgal, and immunized 30 days later with two HC-Ads, HC-Ad22-mCMV-TKnull-WPRE, or HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE, or with a control first generation Ad, Ad-hCMV-HPRT. Again, only mice immunized systemically with the first generation vector Ad-mCMV-HPRT demonstrated the presence of neutralizing antibodies against Ad. HC-Advs elicited a negligible or nonexistent neutralizing antibody response against Ad (Figure 6a) further confirming the reduced ability of HC-Advs in eliciting a systemic humoral anti-Ad immune response, regardless of the vector configuration.

Figure 6. A systemic immunization with high capacity-adenovirus (HC-Ad) elicits an Ad specific T cell response but not neutralizing antibodies.

(a) indicates that anti-Ad neutralizing antibodies are increased 30 days post-immunization only after systemic injection of a first generation Ad vector (Adv) (Ad-hCMV-HPRT), but not following injection of two different HC-Advs. (b) demonstrates that both first generation Adv and HC-Advs elicit an Ad specific T cell response. Splenocytes isolated from animals immunized with first the generation Adv Ad-hCMV-HPRT, or with HC-Advs HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE or HC-Ad22-mCMV-TKnull-WPRE, were co-cultured with heat inactivated Ad capsid proteins and used for an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay. Systemic immunization of all three vectors induced an increase in the frequency of T cells secreting interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in response to stimulation with heat inactivated first generation Advs. hCMV, human cytomegalovirus; HPRT, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; IC, intracranial; mCMV, murine cytomegalovirus; TK, thymidine kinase; WPRE, wood chuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element.

To determine the potential existence of a cellular immune response to HC-Ad we used an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay to test for the presence of a specific T cell response against Ad capsid proteins in animals immunized systemically with HC-Ad or first generation Advs. To do so, animals were immunized systemically with HC-Ad22-mCMV-TKnull-WPRE, HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE, and the control first generation vector Ad-hCMV-HPRT. Animals were killed 7 days after immunization, at the peak of the potential T cell response, and splenocytes were isolated. Heat inactivated Ad-hCMV-HPRT was used to stimulate the splenocytes in vitro against Ad capsid proteins. An ELISPOT assay demonstrated that animals mounted a T-cell immune response against Ad capsid proteins regardless of the vector backbone used for immunization (whether, HC-Ad or first generation Advs) when compared to saline. Immunization with either HC-Ad or first generation Advs elicited an increase in the frequency of anti-Ad T cells secreting interferon-γ (IFN-γ) at 7 days post-immunization (Figure 6b).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we demonstrate that HC-Advs mediate sustained, long-term transgene expression for up to 1 year, even in animals exposed to a systemic immunization against Ad that preceded the injection of the vector into the brain. The experimental model utilized was implemented to mimic the clinical situation in which individuals had been exposed to Ad at a time preceding the delivery of gene therapy. We demonstrate that the systemic immunization with Ad-hCMV-HPRT primes an adaptive immune response that eliminates transgene expression mediated by the first generation Adv Ad-mCMV-βgal. However, this immune response is unable to eliminate transgene expression from the HC-Adv. Our experimental paradigm is designed to test the immune response against virion proteins, rather than the transgene, since the transgene encoded by the Ad used for the systemic immunization [i.e., hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT)] is different from the transgene expressed in the striatum (β-galactosidase).

The immune response to the Ad injected into the brain depends on the precise anatomical site into which the vectors are delivered. Injection of vectors carefully into the brain parenchyma, fail to stimulate a systemic cellular or humoral immune response. Injection of vectors into the brain ventricles, choroid plexus, or meninges, has the potential to stimulate systemic humoral and cellular immune responses. The brain parenchyma’s peculiar immune reactivity is determined by a number of factors including a lack of classical lymphatic outflow channels, absence of professional afferent antigen presenting cells (i.e., dendritic cells),12 the presence of a blood–brain barrier that mainly limits the entry of antibodies into the brain,13 and production of a large number of immune-inhibitory molecules (e.g., transforming growth factor β); the brain ventricles, choroid plexus, and meninges, on the other hand have a population of resident dendritic cells, classical lymphatic outflow channels, and lack a blood–brain barrier. Therefore, the site of injection of vectors into the brain will determine the immune outcome; careful injections that limit the area of transduction to the brain parenchyma itself will not stimulate systemic anti-vector immune responses. If the vector, however, reaches the brain ventricles, a systemic immune response will ensue.14,15 Careful brain vector delivery is thus necessary to avoid priming a systemic immune response, regardless of the vector backbone (whether, first generation or HC-Ad), and regardless of the vector type used. Indeed, the “rules” of brain immune-reactivity described here, apply to any particulate antigen (e.g., including other viruses, and bacille calmette-guérin),14–16 and thus, ought to be taken into consideration in the planning and design of human clinical trials.

Following the administration of first generation Advs to peripheral organs, such as liver and lung, immune responses frequently result in the complete elimination of both vector and transgene expression in 2–3 weeks,17,18 although there are examples when expression from first generation Advs has persisted even in the presence of a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte and/or antibody response.19,20 However, following delivery of viral vectors to the CNS, transgene expression persists for long periods (i.e., 12 months).21,22 When administering injections of either first generation Adv or HC-Adv in the CNS, diligent care must be taken to avoid the ventricles, choroid plexus, and meninges as injection of the vector into these compartments of the brain will result in a systemic immune response capable of eliminating transgene expression from the CNS.14,15,23

In addition, we now demonstrate that the systemic immune reactivity of HC-Ad differs in important aspects from that of first generation Ad. Systemic immunization with first generation Ad causes both a humoral and cellular immune response. Unexpectedly, we determined that a systemic injection of HC-Ad stimulated an increase in the frequency of anti-Ad T cells secreting IFN-γ, but failed to increase the titer of neutralizing anti-Ad antibodies. Concomitantly, immunization with first generation Ad abrogated transgene expression from a first generation Ad injected into the brain, but systemic immunization with HC-Ad failed to do so. Although T cells have always been thought to be responsible for mediating the elimination of transduced cells from the brain, these data suggest that B cells and circulating anti-Ad antibodies may play an important role in the elimination of transgene expression. Previous studies from our laboratory have shown that B cells are necessary for transgene expression loss following anti-Ad immunization.24

The injection of 1 × 107 iu of either a first-generation or HC-Ad into the brain causes a self-limiting, reversible, and innate inflammatory reaction characterized by infiltration of macrophages and lymphocytes, increased expression of major histocompatibility complex class I, activation of local microglia and astrocytes localized to the injection site; however, a statistically significant increase in the expression of cytokine and chemokine genes is only observed at 1 × 108 iu and above.4,25,26 Importantly, this initial innate inflammatory response is transient and does not reduce long-term vector expression. However, acute Ad-induced cytotoxicity is seen when vector doses of ≥108 iu are used to transduce the brain.27 These early innate inflammatory immune responses are caused by Advs, but also by HC-Ad, or ultraviolet/psoralen-inactivated Ad; this confirms that viral genes are not necessary to stimulate innate immune responses.28,29 Nevertheless, continued expression of viral antigens encoded by the first generation Ad may be necessary to stimulate stronger humoral and cellular adaptive immune responses against Ad.3,5,30

This innate response while causing acute cellular- and cytokine-mediated inflammatory reactions, on its own, does not curtail long-term transgene expression from first generation Advs. However, following the stimulation of systemic adaptive anti-Ad immune responses, transgene expression from the first generation Ad is rapidly eliminated.3,27 Following the systemic administration of Ad, an adaptive immune response peaks 7–10 days later.31 This adaptive immune response consists in the generation of Ad capsid, or transgene-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, and capsid neutralizing antibodies.32,33 The adaptive immune response eliminates transgene expression from Ad transduced cells.31,33–36

HC-Advs lack all viral encoding proteins. As a result, the only potential antigenic proteins encountered by the immune system are those that comprise the viral particles (vps) that are directly administered in the HC-Ad dosing regime. On the other hand, first generation Advs retain most of the wild-type viral encoding sequences, and as such, produce viral antigenic proteins in situ. We have established previously that as little as 1 × 106 iu of a first generation Adv delivered systemically stimulates an immune response that eliminates transgene expression in the brain.37 In contrast, the viral capsid protein load associated with the systemic delivery of as many as 2 × 109 vp of the HC-Adv remains below this immunological threshold, being incapable of eliciting an immune response capable of eliminating transgene expression in the CNS. One can conclude that in situ viral gene expression from first generation Advs is responsible for the enhanced immune response capable of eliminating transgene expression from a first generation Adv, compared to the HC-Adv platform.

Mechanisms by which the adaptive immune response inhibits transgene expression have not yet been completely elucidated. Systemic immunization against Ad induces CD8+ and CD4+ T cells to infiltrate those areas of the brain that had been transduced with Adv. This immune response is able to significantly decrease the number of transgene expressing cells through a mixture of cytotoxic and non-cytotoxic mechanisms.38–40 Rats infected with an Ad whose transgene is expressed mainly in astrocytes show an elimination of the transgene and viral genomes with evidence of cell death.7 Both responses are mediated by CD8+ and/or CD4+ positive T cells. In mice, similar responses are encountered, with responses depending on CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factorα, and perforin. Thus, complex immune mechanisms mediate the elimination of transduced brain cells; the final response is determined by the vector used, the transcriptional cassette encoded, the species, and the strain of experimental animal.

These results indicate that the use of first generation Ad is limited in immune competent individuals, making it necessary to develop vectors that are as close as possible to being invisible to the adaptive immune system. Thus, for first generation Ad long-term expression can only be achieved in the absence of stimulation of the systemic adaptive immune response. HC-Ad, however, are able to sustain long-term expression even in the presence of such an adaptive immune response that can clear most of the cells transduced by a first generation Ad in the CNS.

Since a majority of the human population is likely to have been exposed to Ad,41 and considering the difficulties in determining whether exposure to Ad has indeed occurred, it is important to develop vectors that can deliver sustained, safe, long-term transgene expression (in the presence of systemic adaptive immune responses against Ad). Using a pre-immunization paradigm, the experiments described here mimic as closely as possible (in a rodent model), the condition of many human patients likely to undergo gene therapy for a neurological disorder. Even the use of human Ad is unlikely to induce a stronger immune response due to the inability of human Ad to replicate in rodents. The mechanisms underlying the detrimental effects (of the combined humoral and cellular immune response) on brain viral vector-mediated transgene expression, following the systemic delivery of Adv remain to be fully elucidated. Nevertheless, we move forward toward human clinical trials using HC-Adv for treating neurological disorders such as glioma and Parkinson’s disease.

It is in order to solve this problem that HC-Ads or more commonly, “gutless” Ad have been developed, in which the entire viral genome is absent, a manipulation that makes vectors less immunogenic. Previous studies in rats have shown the potential of HC-Ads in providing long-term expression in animals pre-immunized against Ad;27 however, these previous studies had been limited to a short time post-vector delivery, not addressing the issue of how stable the expression from vectors actually would be in the presence of systemic immune responses that abolish expression from first generation vectors in under a month. This study now demonstrates that expression from HC-Ad is truly very long-term, being sustained for up to 1 year.

Other groups have demonstrated that systemic HC-Ad delivery elicits neutralizing antibodies against Ad42 or cytotoxic T-lymphocytes.43 However, our study has shown that the two different HC-Ad preparations developed in our laboratory are incapable of inducing neutralizing antibodies against Ad. At this time we can only speculate about the cause for these different responses. It could be that the particular species and strains used, the dose of vectors injected, the number of vector injections, and the purity of the vectors, could all influence the capacity to induce a humoral immune response. Although the reasons for the differences have not been investigated in our experiments, it will be important to do so in the future, especially if HC-Ad were to be used to stimulate humoral immune responses.

HC-Ad induces transgene expression in astroglia and neurons. Importantly, for therapies to be effective, vectors need to elicit transgene expression within different cell types in the brain, i.e., neurons, astrocytes, and/or oligodendrocytes. Advs have a number of positive characteristics, including the ability to infect many different cell types, both dividing and non-dividing, and have an extremely low probability of random integration into the host chromosomes. The brain cell-type expressing vector-encoded transgenes differed between the vectors used. Cell-type expression depends on the promoter elements utilized; however, in the context of viral vectors, transgene expression also depends on other factors. For example, from the vector’s perspective, the vector backbone and the transgene itself can influence transgene expression; in addition, the species, strain, and sex, also affect transgene expression. How each of these elements is weighed in the final outcome is still poorly understood. Nevertheless, both vectors express mostly in brain astrocytes, and our data conclusively demonstrate long-term expression from a HC-Adv and only short-term expression from a first-generation Adv in the presence of a pre-existing systemic anti-Ad immune response. It will be important to fully elucidate all factors that influence cell-type specific transgene expression.

In summary, we demonstrate that novel helper-dependent HC-Adv sustain transgene expression for up to 1 year, even when injected into the brains of animals immunized against Ad preceding brain gene transfer. This strongly supports the use of HC-Ad for gene transfer into the brain, not only for short-term gene expression, but also for long-term gene expression, and potentially for gene therapy in human neurological diseases. Further, the incapacity of HC-Ad to induce systemic anti-Ad immune responses further supports the safety and potential efficacy of these vectors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

First generation Adv development

Ad-mCMV-βgal (previously referred to as RAd36) and Ad-hCMV-HPRT (previously referred to as RAdHPRT) are first-generation, replication defective serotype 5 Advs with deletions in their E1 and E3 regions.3–6,44,45 Ad-mCMV-βgal contains an expression cassette consisting of Escherichia coli β-galactosidase gene driven by a 1.4-kilobase fragment from the major-immediate-early, murine cytomegalovirus promoter (mCMV). Ad-hCMV-HPRT contains an expression cassette consisting of the HPRT gene driven by the human cytomegalovirus (hCMV) intermediate-early promoter.

HC-Adv development

HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE and HC-Ad22-mCMV-TKnull-WPRE are novel HC-Advs (Figure 7) and were developed as follows:

Figure 7. Schematic representation of pC22.mCMV β gal.WPRE and pC22.mCMV.TKnull.WPRE plasmids.

(a) Plasmid map of pC22.mCMV. βgal.WPRE (left panel) and pC22.mCMV.TKnull.WPRE (right panel) indicates the constituents and orientation of the murine cytomegalovirus (mCMV)-driven β-galactosidase (β-gal) and TKnull cassettes respectively. Both expression cassettes contain a wood chuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element (WPRE). pC22.mCMV.TKnull.WPRE does not express herpes simplex virus 1 thymidine kinase due to the removal of its stop codon (b) Gel electrophoresis and restriction map analysis of pC22.mCMV.βgal.WPRE (left panel) and pC22.mCMV.TKnull. WPRE (right panel) plasmid were used to check for expected sizes. Lanes are as follows: lane 1, Hyperladder; lane 2, undigested plasmid; lane 3, HindIII digest; lane 4, PmeI digest; lane 5, EcoRV digest; lane 6, NotI + AscI digest; lane 7, Hyperladder. Note: An additional EcoRV site is present 104 base pair (bp) downstream from the site indicated in the TKnull transgene but is not illustrated in the schematic diagram for simplicity. (c) Linear depiction of HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE (top panel) and HC-Ad22-mCMV-TKnull-WPRE (bottom panel). The constructs indicate the individual components and the orientation of the cassettes as well as the constituents of the HC-Ad22 vector genome including left and right inverted terminal repeat (ITR)’s, packaging domain, and three inert stuffer sequences. TK, thymidine kinase.

Polymerase chain reaction amplification of the Ad and stuffer sequences and engineering of the high capacity backbone plasmid pC22

Ad sequences corresponding to the left ITR plus the packaging signal (Ψ) (L-ITR-Ψ), and the right (R-ITR) were polymerase chain reaction amplified. A 451-basepair (bp) DNA fragment of human Ad type 5 left-end sequence that includes the L-ITR was generated using the primers: L-ITR forward: 5′-TGTGTGGTACCGTTTAAACCATCATCAATAATAACCTTTTGGATTGAAGC-3′; and L-ITR reverse: 5′-GTGTGT GAGCTCGGCGCGCCGTGTGTTTAATTAAAAAACGCCAACTTGACCCGGAACG-3′. A 480-bp DNA fragment human Ad type 5 right-end sequence that includes the E4 promoter and the R-ITR was generated using the primers: R-ITR forward 5′-GTGTGTGGCGCGCCGTGTGTGCGGCCGCCCTTACCAGTAAAAAAGAAAAGGTATTAAAAAAACACC-3′; and R-ITR reverse 5′-GTGGTGTGAGCTCGTTTAAACCATCATCAATAATATACCTTATTTTGGATTGAAGC-3′.

Stuffer 1 (7,990 bp) was amplified from the human chromosome 22q 11.2 contig AC000093 by using the primers: Stuffer 1 forward 5′-GTGTGTGGCGCGCCCCATCAATGATGCAGGAAAAGAGGCTCTGGTCACC-3′; and Stuffer 1 reverse 5′-GTGTGTGCGGCCGCGCTGAGGCCAGGAGTGCCTGTGTGG-3′. Stuffer 2 (8,007 bp) was amplified from the human chromosome 22q 11.2 contig AC004463 by using the primers: Stuffer 2 forward 5′GTGTGTTTAATTAACTTAGTCTTGGGAAAACTGAGATGCAGATGCCTGGTCGTCACC-3′; and Stuffer 2 reverse 5′-GTGTGTGGCGCGCCCAAATCCATCCATGTGTCCCCCCTGTGGTCTGTGTGTGACACC-3′. Stuffer 3 (8,994 bp) was amplified from the human chromosome 22q 11.2 contig AC000551 by using the primers: Stuffer 3 forward 5′-GTGTGTTTAATTAATTTCAGTAGGTGCCCAATAAATGTTTGTGGG-3′; and Stuffer 3 reverse 5′-GTGTGTTTAATTAAAAGAAACTACCAGACTGTTTTCCAAAGTGGCTGCACC-3′. The three stuffer sequences were combined with the L-ITR-Ψ and R-ITR to generate the generating HC-Adv plasmid pC22 (28,922 bp).

The transgene cassette [mCMV-βGal-WPRE-polyA], was cloned into pC22 generating the vector pC22.mCMV.βGal.WPRE (31,581 bp) (Figure 7). The transgene cassette [mCMV-TKnull-WPRE-polyA], was cloned into pC22 generating the vector generating the vector pC22. mCMV.TK.WPRE (29,558 bp) (Figure 7). Testing of this vector in vitro indicated that herpes simplex virus 1 thymidine kinase activity is not detected in infected cells, and furthermore, herpes simplex virus 1 thymidine kinase immunoreactivity is also undetectable from infected cells. Thus, since neither herpes simplex virus 1 thymidine kinase activity nor immunoreactivity is expressed from this HC-Adv, we decided to utilize this vector as a control HC-Ad for immunization (Figure 7).

Vector rescue, scale up, purification, and characterization

First generation vectors were scaled as described previously.5,44 High capacity vectors were rescued and scaled up as described in detail previously.46,47

First generation vectors were titered for both total viral particles (vps/ml)44 and for iu [plaque forming units (PFU)/ml].44 The titers determined were as follows: Ad-mCMV-βgal45 was 2.51 × 1012 vps/ml and 8.19 × 1010 PFU/ml, Ad-hCMV-HPRT3–6 was 3.63 × 1012 vp/ml and 3.28 × 1011 PFU/ml. High capacity vectors were titered for total viral particles (vp/ml), blue forming units (bfu/ml), and contaminating helper virus (PFU/ml).44,48 The titers determined were as follows: HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal.WPRE was 5.5 × 1012 vps/ml, 1.64 × 1012 bfu/ml, and 1 × 105 PFU/ml; HC-Ad22-mCMV-TK-null-WPRE was 1.1 × 1013 vps/ml and 1 × 105 PFU/ml.

The vector preparations were screened for the presence of replication competent Ad44 and for lipopolysaccharide contamination (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ).44 Virus preparations used were free from replication competent Ad and lipopolysaccharide contamination.

Animals and surgical procedures

Female C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were injected systemically (using an intraperitoneal injection) with either 3.28 × 108 PFU of Ad-hCMV-HPRT in 100 μl of solution (n = 120) or saline (n = 120). Thirty days after viral vector systemic immunization mice were anesthetized using ketamine (75 mg/kg) and medetomidine (0.5 mg/kg) and injected into the right striatum as previously described24 with 1 × 107 PFU of first generation Adv Ad-mCMV-βgal (n = 120) or 1 × 107 bfu of HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE (n = 120). At experimental endpoints (14, 30, 60 90, 180, and 365 days) mice were anesthetized.24 All animal experiments were performed after prior approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to the policies and procedures of the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Comparative Medicine Department.

We also performed experiments to determine if HC-Ad can induce a systemic anti-Ad immune response upon intraperitoneal injection. To do so, we immunized female C57Bl/6 mice 30 days following an intracranial injection of Ad-mCMV-βgal. Systemic immunization consisted of either the injection of 2 × 109 vps of HC-Ad22-mCMV-βgal-WPRE (n = 10), 2 × 109 vps of HC-Ad22-mCMV-TK-null-WPRE (n = 10), or 3.28 × 108 PFU of Ad-hCMV-HPRT (n = 10) or saline (n = 10). Animals were killed 30 or 60 days after the systemic injection as described above.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Sections of the striatum (50 μm) were used for immunohistochemistry to detect transgene expression or specific immune cells using methodologies described previously.7 The primary antibodies used for immunohistochemical staining were the following: rabbit polyclonal anti-β-galactosidase (1:1,000) (produced by us49); Chicken anti microtubule-associated protein-2 (1:500) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), Guinea Pig anti glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:500) (Advanced Immunochemical, Long Beach, CA), mouse anti myelin basic protein (1:1,000) (Chemicon, Billerica, MA) and rat anti-mouse CD8α (1:1,000) (Serotec, Raleigh, NC). Appropriate secondary antibodies were used: biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (1:800), biotin-conjugated goat anti-rat immunoglobulin G (1:800) (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), Texas Red conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:1,000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-chicken (1:1,000), Alexa 594-conjugated goat anti-Rabbit (1:1,000), Alexa 647-conjugated goat anti Guinea Pig (1:1,000), Alexa 594-conjugated goat anti mouse (1:1,000) (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA).

Quantification and sterological analysis

e number of labeled cells were quantified as previously described.50 Data was expressed as an absolute number of positive cells in each anatomical region analyzed. Results were expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Confocal imaging

Sections were examined by confocal microscopy as described previously.7

Neutralizing antibody assay

Neutralizing antibody titers were measured in serum samples taken from mice that were killed at specific points of time following intraperitoneal injection of Adv as described.27 Results were expressed as the mean ± SEM.

ELISPOT assay

As a measure of the cell-mediated immune response to Ad we assessed the frequency of IFN-γ-producing T cells using the ELISPOT kit assay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, splenocytes (1 × 106 cells/well) were cultured in Millipore MultiScreen-HA plates (coated with anti-IFN-γ antibody) for 24 hours in X-Vivo media (Cambrex, Baltimore, MD) containing 1 × 109 PFU/ml of heat-inactived recombinant Ad Ad-hCMV-HPRT (inactivated at 85 °C for 15 minutes). The wells were then washed and incubated overnight at 4 °C with biotinylated anti-IFN-γ detection antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Reactions were visualized using streptavidin-alkaline phosphastase, and 5-bromo-4-chromo-3-indolylphosphatase p-toluidine salt, and nitro blue tetrazolium chloride as substrate. The number of spots per 106 splenocytes, which represents the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells, was counted with the KS ELISPOT automated image analysis system (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Results were expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by using one or two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s test; results were expressed as the mean ± SEM. A P value < 0.05 was considered the cut off for significance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [grant nos. 1 RO1 NS 42893.01, U54 NS045309-01, and 1R21 NS047298-01] (P.R.L.), and The Bram and Elaine Goldsmith Chair In Gene Therapeutics (P.R.L.); National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [grant no. 1R01 NS44556.01], National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [grant no. 1 RO3 TW006273-01] (M.G.C.), and The Medallion Chair in Gene Therapeutics (M.G.C.); and The Linda Tallen and David Paul Kane Foundation Annual Fellowship (M.G.C., P.R.L.). P.N. is supported by grant no. R01DK067324. We also thank the generous funding our Institute receives from the Board of Governors at Cedars Sinai Medical Center. The authors have no conflicting financial interests. We thank the support and academic leadership of Shlomo Melmed and David Meyer (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and David Geffen School of Medicine).

References

- 1.Trask TW, Trask RP, Aguilar-Cordova E, Shine HD, Wyde PR, Goodman JC, et al. Phase I study of adenoviral delivery of the HSV-tk gene and ganciclovir administration in patients with current malignant brain tumors. Mol Ther. 2000;1:195–203. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Immonen A, Vapalahti M, Tyynela K, Hurskainen H, Sandmair A, Vanninen R, et al. AdvHSV-tk gene therapy with intravenous ganciclovir improves survival in human malignant glioma: a randomised, controlled study. Mol Ther. 2004;10:967–972. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas CE, Birkett D, Anozie I, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Acute direct adenoviral vector cytotoxicity and chronic, but not acute, inflammatory responses correlate with decreased vector-mediated transgene expression in the brain. Mol Ther. 2001;3:36–46. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zirger JM, Barcia C, Liu C, Puntel M, Mitchell N, Campbell I, et al. Rapid upregulation of interferon-regulated and chemokine mRNAs upon injection of 108 international units, but not lower doses, of adenoviral vectors into the brain. J Virol. 2006;80:5655–5659. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00166-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas CE, Schiedner G, Kochanek S, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Peripheral infection with adenovirus causes unexpected long-term brain inflammation in animals injected intracranially with first-generation, but not with high-capacity, adenovirus vectors: toward realistic long-term neurological gene therapy for chronic diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7482–7487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120474397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas CE, Schiedner G, Kochanek S, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Preexisting antiadenoviral immunity is not a barrier to efficient and stable transduction of the brain, mediated by novel high-capacity adenovirus vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:839–846. doi: 10.1089/104303401750148829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barcia C, Thomas CE, Curtin JF, King GD, Wawrowsky K, Candolfi M, et al. In vivo mature immunological synapses forming SMACs mediate clearance of virally infected astrocytes from the brain. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2095–2107. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kochanek S, Clemens PR, Mitani K, Chen HH, Chan S, Caskey CT. A new adenoviral vector: replacement of all viral coding sequences with 28 kb of DNA independently expressing both full-length dystrophin and β-galactosidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5731–5736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parks RJ, Chen L, Anton M, Sankar U, Rudnicki MA, Graham FL. A helper-dependent adenovirus vector system: removal of helper virus by Cre-mediated excision of the viral packaging signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13565–13570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umana P, Gerdes CA, Stone D, Davis JR, Ward D, Castro MG, et al. Efficient FLPe recombinase enables scalable production of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors with negligible helper-virus contamination. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:582–585. doi: 10.1038/89349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Addison CL, Braciak T, Ralston R, Muller WJ, Gauldie J, Graham FL. Intratumoral injection of an adenovirus expressing interleukin 2 induces regression and immunity in a murine breast cancer model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8522–8526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMenamin PG. Distribution and phenotype of dendritic cells and resident tissue macrophages in the dura mater, leptomeninges, and choroid plexus of the rat brain as demonstrated in wholemount preparations. J Comp Neurol. 1999;405:553–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bechmann I, Galea I, Perry VH. What is the blood-brain barrier (not)? Trends Immunol. 2007;28:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matyszak MK, Perry VH. The potential role of dendritic cells in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases in the central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1996;74:599–608. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevenson PG, Hawke S, Sloan DJ, Bangham CR. The immunogenicity of intracerebral virus infection depends on anatomical site. J Virol. 1997;71:145–151. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.145-151.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cartmell T, Southgate T, Rees GS, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR, Luheshi GN. Interleukin-1 mediates a rapid inflammatory response after injection of adenoviral vectors into the brain. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1517–1523. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01517.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elkon KB, Liu CC, Gall JG, Trevejo J, Marino MW, Abrahamsen KA, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha plays a central role in immune-mediated clearance of adenoviral vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9814–9819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang R, Zhang X, Zhang J, Xiu R. Gene transfer of vascular endothelial growth factor plasmid/liposome complexes in glioma cells in vitro: the implication for the treatment of cerebral ischemic diseases. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2000;23:303–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wadsworth SC, Zhou H, Smith AE, Kaplan JM. Adenovirus vector-infected cells can escape adenovirus antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte killing in vivo. J Virol. 1997;71:5189–5196. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5189-5196.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tripathy SK, Black HB, Goldwasser E, Leiden JM. Immune responses to transgene-encoded proteins limit the stability of gene expression after injection of replication-defective adenovirus vectors. Nat Med. 1996;2:545–550. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zermansky AJ, Bolognani F, Stone D, Cowsill CM, Morrissey G, Castro MG, et al. Towards global and long-term neurological gene therapy: unexpected transgene dependent, high-level, and widespread distribution of HSV-1 thymidine kinase throughout the CNS. Mol Ther. 2001;4:490–498. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soudais C, Skander N, Kremer EJ. Long-term in vivo transduction of neurons throughout the rat CNS using novel helper-dependent CAV-2 vectors. FASEB J. 2004;18:391–393. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0438fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matyszak MK. Inflammation in the CNS: balance between immunological privilege and immune responses. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;56:19–35. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zirger JM, Liu C, Barcia C, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Immune regulation of transgene expression in the brain: B cells regulate an early phase of elimination of transgene expression from adenoviral vectors. Viral Immunol. 2006;19:508–517. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.19.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowenstein PR. Un pour tous, tous pour un. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:467–468. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01648-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byrnes AP, Rusby JE, Wood MJ, Charlton HM. Adenovirus gene transfer causes inflammation in the brain. Neuroscience. 1995;66:1015–1024. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00068-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas CE, Abordo-Adesida E, Maleniak TC, Stone D, Gerdes G, Lowenstein PR. Gene transfer into rat brain using adenoviral vectors. In: Gerfen JN, McKay R, Rogawski MA, Sibley DR, Skolnick P, editors. Current Protocols in Neuroscience. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 2000. pp. 4.23.21–24.23.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Q, Zaiss AK, Colarusso P, Patel K, Haljan G, Wickham TJ, et al. The role of capsid-endothelial interactions in the innate immune response to adenovirus vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:627–643. doi: 10.1089/104303403321618146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muruve DA. The innate immune response to adenovirus vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:1157–1166. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kafri T, Morgan D, Krahl T, Sarvetnick N, Sherman L, Verma I. Cellular immune response to adenoviral vector infected cells does not require de novo viral gene expression: implications for gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11377–11382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Ertl HC, Wilson JM. MHC class I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes to viral antigens destroy hepatocytes in mice infected with E1-deleted recombinant adenoviruses. Immunity. 1994;1:433–442. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y, Nunes FA, Berencsi K, Furth EE, Gonczol E, Wilson JM. Cellular immunity to viral antigens limits E1-deleted adenoviruses for gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4407–4411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Li Q, Ertl HC, Wilson JM. Cellular and humoral immune responses to viral antigens create barriers to lung-directed gene therapy with recombinant adenoviruses. J Virol. 1995;69:2004–2015. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2004-2015.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barr D, Tubb J, Ferguson D, Scaria A, Lieber A, Wilson C, et al. Strain related variations in adenovirally mediated transgene expression from mouse hepatocytes in vivo: comparisons between immunocompetent and immunodeficient inbred strains. Gene Ther. 1995;2:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dai Y, Schwarz EM, Gu D, Zhang WW, Sarvetnick N, Verma IM. Cellular and humoral immune responses to adenoviral vectors containing factor IX gene: tolerization of factor IX and vector antigens allows for long-term expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1401–1405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Y, Wilson JM. Clearance of adenovirus-infected hepatocytes by MHC class I-restricted CD4+ CTLs in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;155:2564–2570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barcia C, Gerdes C, Xiong W, Thomas CE, Liu C, Kroeger KM, et al. Immunological thresholds in neurological gene therapy: highly efficient elimination of transduced cells may be related to the specific formation of immunological synapses between T cells and virus-infected brain cells. Neuron Glial Biology. 2007;2:309–327. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X07000579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byrnes AP, Wood MJ, Charlton HM. Role of T cells in inflammation caused by adenovirus vectors in the brain. Gene Ther. 1996;3:644–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kajiwara K, Byrnes AP, Charlton HM, Wood MJ, Wood KJ. Immune responses to adenoviral vectors during gene transfer in the brain. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:253–265. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.3-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wood MJA, Byrnes AP, McMenamin M, Kajiwara K, Vine A, Gordon I, et al. Immune responses to viruses: practical implications for the use of viruses as vectors for experimental and clinical gene therapy. In: Lowenstein PR, Enquist LW, editors. Protocols for Gene Transfer in Neuroscience. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1996. pp. 365–376. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chirmule N, Propert K, Magosin S, Qian Y, Qian R, Wilson J. Immune responses to adenovirus and adeno-associated virus in humans. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1574–1583. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parks R, Evelegh C, Graham F. Use of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors of alternative serotypes permits repeat vector administration. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1565–1573. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muruve DA, Cotter MJ, Zaiss AK, White LR, Liu Q, Chan T, et al. Helper-dependent adenovirus vectors elicit intact innate but attenuated adaptive host immune responses in vivo. J Virol. 2004;78:5966–5972. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5966-5972.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Southgate T, Kingston P, Castro MG. Gene transer into neural cells in vivo using adenoviral vectors. In: Gerfen CR, McKay R, Rogawski MA, Sibley DR, Skolnick P, editors. Current Protocols in Neuroscience. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 2000. pp. 4.23.21–24.23.40. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerdes CA, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Strong promoters are the key to highly efficient, noninflammatory and noncytotoxic adenoviral-mediated transgene delivery into the brain in vivo. Mol Ther. 2000;2:330–338. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ng P, Parks RJ, Graham FL. Preparation of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors. Methods Mol Med. 2002;69:371–388. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-141-8:371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palmer D, Ng P. Improved system for helper-dependent adenoviral vector production. Mol Ther. 2003;8:846–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiong W, Goverdhana S, Sciascia SA, Candolfi M, Zirger JM, Barcia C, et al. Regulatable gutless adenovirus vectors sustain inducible transgene expression in the brain in the presence of an immune response against adenoviruses. J Virol. 2006;80:27–37. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.27-37.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith-Arica JR, Morelli AE, Larregina AT, Smith J, Lowenstein PR, Castro MG. Cell-type-specific and regulatable transgenesis in the adult brain: adenovirus-encoded combined transcriptional targeting and inducible transgene expression. Mol Ther. 2000;2:579–587. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suwelack D, Hurtado-Lorenzo A, Millan E, Gonzalez Nicolini V, Wawrowsky K, Lowenstein PR, et al. Neuronal expression of the transcription factor Gli1 using the Tubulin a-1 promoter is neuroprotective in an experimental model of Parkinson’s disease. Gene Therapy. 2004;11:1742–1752. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]