Abstract

Researchers have conducted numerous pre-clinical and clinical gene transfer studies using recombinant viral vectors derived from a wide range of pathogenic viruses such as adenovirus, adeno-associated virus, and lentivirus. As viral vectors are derived from pathogenic viruses, they have an inherent ability to induce a vector specific immune response when used in vivo. The role of the immune response against the viral vector has been implicated in the inconsistent and unpredictable translation of pre-clinical success into therapeutic efficacy in human clinical trials using gene therapy to treat neurological disorders. Herein we thoroughly examine the effects of the innate and adaptive immune responses on therapeutic gene expression mediated by adenoviral, AAV, and lentiviral vectors systems in both pre-clinical and clinical experiments. Furthermore, the immune responses against gene therapy vectors and the resulting loss of therapeutic gene expression are examined in the context of the architecture and neuroanatomy of the brain immune system. The chapter closes with a discussion of the relationship between the elimination of transgene expression and the in vivo immunological synapses between immune cells and target virally infected brain cells. Importantly, although systemic immune responses against viral vectors injected systemically has thought to be deleterious in a number of trials, results from brain gene therapy clinical trials do not support this general conclusion suggesting brain gene therapy may be safer from an immunological standpoint.

“The world does not speak. Only we do.” Richard Rorty, Contingency, irony, and solidarity, 1989.

1. INTRODUCTION

Gene therapy is an attractive and promising tool for the treatment for neurological disorders. Viral vectors are ideal gene delivery vehicles to the CNS due to their ability to infect both dividing and non-diving cells and the ability to produce stocks of concentrations high enough to use as doses small enough required for administration to the nervous system. Numerous pre-clinical and clinical experiments have been performed using gene therapy strategies to treat neurological disorders including Parkinson's disease[During et al., 2001; Muramatsu et al., 2002; Wong et al., 2006; Kaplitt et al., 2007], Alzheimer's disease [Levi-Montalcini, 1987; Eriksdotter Jonhagen et al., 1998; Tuszynski et al., 2005], and glioma[Chiocca et al., 2004; Immonen et al., 2004; Aliet al., 2005]. Unfortunately, researchers have often had difficulty translating the success of preclinical animal gene therapy experiments into significant therapeutic outcomes in the clinic. The patient's immune response to the viral vector is a logical culprit for the lack of substantial therapeutic benefits in clinical trails for the treatment of neurological disorders. Here we examine the immune response against gene therapy vectors in the brain. Particular attention is paid to the unique immunological status of the brain. Transgene expression in the CNS mediated by first generation and high capacity, helper dependant adenoviral vectors is explored in the context both the both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system.

2. BRAIN IMMUNE REACTIVITY. LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

The type of immune responses that will be induced as a consequence of viral vector delivery into the brain will depend on which of the two main immune compartments will be targeted by the therapeutic viral vectors. Brain ventricles, meninges and choroid plexi contain all cellular, vascular and lymphatic elements of the immune system, as do most other organs in the body. This includes dendritic cells (DC), the major cell type capable of inducing primary T cell responses. DCs are located within the meninges, choroid plexus and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of the normal non-inflamed brain [McMenamin, 1999; Pashenkov et al., 2003]. These DCs are strategically located to capture foreign or self antigens. From their location throughout the brain ventricular system they can migrate to deep cervical lymph nodes (CLN), the primary lymph nodes draining the brain and CSF [Cserr et al., 1992]. The second brain immune compartment, the brain parenchyma itself, is devoid of DCs, typical lymphatic vessels, and is separated from the general circulation by the blood brain barrier formed by tight intercellular endothelial junctions[Bechmann et al., 2007]. A large number of molecular mechanisms serve to dampen immune reactivity in the brain parenchyma itself.

What are the immune consequences of making antigens available to either of the brain immune compartments? Injection of a particulate antigen or infectious agent (e.g. live influenza virus, BCG, non-replicative adenoviral vectors) only into the brain parenchyma causes innate inflammatory responses, but does not trigger systemic adaptive immune responses[Matyszak et al., 1996; Stevenson et al., 1997b; Cartmell et al., 1999; Lowenstein, 2002]; i.e. the systemic immune system remains ignorant of the delivery of antigens into the brain. However, injection of the same type of antigen into the ventricular system, will stimulate an innate inflammatory and a systemic adaptive immune response [Matyszak et al., 1996; Stevenson et al., 1997a; Matyszak, 1998]. Different rules apply upon the injection of a soluble diffusible ligand. Thus, injection of a soluble diffusible antigen (e.g. OVA) into either compartment, does induce a systemic B cell response [Knopf et al., 1998]. The reason for this is that independent of its site of delivery, the antigen will diffuse to reach the CLN and stimulate a systemic humoral immune response. Particulate antigens carefully delivered to the brain parenchyma fail to do so because they cannot diffuse out into the ventricular system to reach the CLN.

The differential distribution of DCs is very important to organize these differing brain immune responses. Throughout the body, DCs localize predominantly to lymphoid tissue, where they take up antigen and mature to potent antigen presenting cells (APC). Alternatively they acquire antigen at inflamed sites from where they migrate to secondary lymphoid organs to activate naïve T cells[Caux et al., 2000; Leon et al., 2007].

Could DCs follow similar pathways during brain infections, or inflammatory states caused by various agents including gene therapy vectors? DC could take up antigens in the brain ventricles, mature, and migrate to CLN. Alternatively, antigens could drain directly into deep CLN by diffusion. A possible reason underlying the different immune responses upon antigen delivery to either brain ventricles or parenchyma may be due to inability of particulate antigen to move from the brain parenchyma to the CLN, using either diffusion or cellular transport. Thus, particulate antigens injected into the brain parenchyma, though they may cause inflammation, are never transported to the lymph nodes to prime a systemic immune response, and thus, the systemic immune system remains ignorant of their presence. Soluble antigens on the other hand can and will diffuse from the brain to the ventricles, reach the lymph nodes, and stimulate systemic adaptive immune responses.

Independently of antigen transport routes to the lymph nodes, naïve T cells are primed in the CLN, expand, exit the lymph nodes, and traffic to the site of insult, where they will exert their effector function upon antigen re-encounter. Thus, although DCs can enter the CNS parenchyma during inflammation to sustain T cell function, initial T cell activation preceding disease onset is most likely to occur in the CLN. During chronic inflammation, however, brain infiltrating DC have been proposed to be able to present antigen to naïve T cells[McMahon et al., 2005].

3. IMMUNE RESPONSES AGAINST VIRAL VECTORS USED IN GENE THERAPY

a. Innate Immune Responses. Kickstarting the Defense

As many gene therapy strategies employ viral vector technology, the immunogenicity of the gene therapy must be thoroughly evaluated and characterized. Delivery of viral vectors into the CNS induces acute inflammation including microglial activation, macrophage recruitment, and antigen-non specific T cell infiltration. This innate immune response is dose-dependant and independent of the immune status of the particular compartment of the CNS to which the viral vectors are delivered. As recombinant viral vectors are packaged into identical capsids as wild type viruses, the two are indistinguishable by the immune system. In most cases the interaction between viral capsid proteins and specific innate immune receptors, such as Toll receptors, mediates the initial inflammatory response Due to the compartmentalization of the brain's immune system, injection of viral vectors into the immune-privileged brain parenchyma stimulates innate inflammatory responses without necessarily inducing a linked systemic adaptive immune response.

In a detailed dose response study, we examined the short term (3 days) and medium-to long term (30 days) inflammatory consequences of injecting increasing doses of adenoviral vectors delivered in small volumes directly into the mouse striatum[Thomas et al., 2001a]. A limited dose (small volume and low dose) of an adenoviral vector delivered directly into the brain parenchyma will not stimulate the systemic adaptive immune response. The limited, if any, availability of vector antigens to the general systemic circulation and lymphoid organs is thought to contribute to this systemic immune ignorance, and thus, lack of priming of an adaptive anti-vector immune response.

Vector doses ranging from 106 to 109 infectious units were injected directly into the striatum. Both transgene expression and cellular inflammation, including microglia activation, macrophage infiltration, antigen-non specific T cell recruitment, were evaluated at three and thirty days after vector administration. β-galactosidase expression was detected a early as 3 days post vector injection in brains injected with 106 infectious units. While expression levels increased with escalating doses, a plateaue was reached following administration of 108 infectious units of vector. In addition, cytotoxicity also increased in parallel with increasing doses of vectors injected. Minimal local cytotoxicity was observed at doses below 108 iu, but immuno-reactivity for the astrocyte marker GFAP and the neuronal marker NeuN suggested a substantial loss of astrocytes and neurons following the injection of 109 iu. Importantly, administration of high doses of heat inactivated adenoviral vectors (1×109 iu) failed to cause any significant inflammation and/or leukocyte infiltration into the brain. These data demonstrates that acute toxicity is indeed caused by intact viral particles, but not the viral proteins or vector genomes[Thomas et al., 2001a].

Importantly, when studied for medium-to long term periods of time (i.e. 30 days post intracranial vector injection) doses of vectors that elicited an increased inflammatory response consisting of increased markers for monocytes and lymphocytes at 3 days, had a corresponding elimination of transgene expression at 30 days; i.e., reduced transgene expression at doses of 108, and complete abrogation of transgene expression following the injection of 109 iu. However, stable transgene expression at 30 days was observed at the doses of 106 and 107.

TUNEL staining revealed an increase of apoptotic cells demonstrating cytotoxicity was caused by the acute inflammatory induced cell death resulting from the dose of 109 infectious units. Thomas et al. detected increases in persistent brain inflammation and activation of microglia, and continued presence of monocytes and leukocytes corresponding to an increase in the brain cell loss. Acute cytotoxicity was directly correlated with the long term persistence of macrophages, CD8+ T cells, and increased expression of MHC-I in the CNS. There was also a positive correlation between short-term and medium-to long term (>30 days) brain cellular inflammation and long term loss of transgene expression from adenoviral vectors. Inversely, when brains injected with noncytotoxic doses (i.e. below 1×108) were examined 30 days later, any initial inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltration and microglia activation had completely resolved. These data indicate that the acute innate inflammatory response caused by intracranial injection of adenoviral vectors in naïve animals is dose-dependent, transient, and self-limiting. Moreover, doses less than 1×108 provide therapeutically accepted levels of transgene expression without any long term inflammation, monocyte recruitment, or cytotoxicity.

In a follow-up work, we demonstrated that interferon regulated, and chemokine mRNAs were not unregulated[Zirger et al., 2006] at the non-cytotoxic doses established in the work of Thomas et al.[Thomas et al., 2001a] Also using a dose-response regime of increasing doses of adenovirus from 105 to 108, Zirger et al only observed an increase in αβ-interferon-regulated genes such as OAS, IRF-1, and PKR; and chemokines, such as RANTES, MCP-1, and IFN-γ-inducible protein 10, were only significantly increased at the dose of 108 infectious units, thus, above the threshold established for activation of local microglia, and recruitment of circulating mononuclear cells, established by Thomas et al.[Thomas et al., 2001a] Moreover production of mRNAs for αβ-interferon-regulated genes and chemokines was transient with expression of most mRNAs returning to baseline by 7 days post-injection into the brain. This indicates that innate inflammatory responses to adenovirus (i.e. increase in expression of interferon-inducible genes, and chemokine genes) are dose-dependent. The injection of adenoviral vectors above a particular threshold increases expression of chemokines and induces local cytotoxicity. Once this inflammatory threshold is crossed, long-term, potentially chronic (i.e., 6 months) brain inflammation can be expected.[Dewey et al., 1999]

b. Thresholds: A Guide to the Administration of Safe Gene Therapy

The inflammatory threshold to intracranial delivery of adenoviral vectors injected into the brain is 1 × 108 iu; once this threshold is crossed, increased expression of interferon-inducible and chemokine-encoding genes, the activation of local microglia, and the recruitment of circulating monocytes and lymphocytes is observed. Injections of vector doses below this threshold do not induce any innate increased recruitment of inflammatory cells to the brain, do not cause glial or neuronal toxicity, do not cause an increase in expression of interferon-regulated genes or chemokine genes, and achieve long term transgene expression of at least up to one year (Barcia et al. In Press). The consequences of this work demonstrate the necessity to consider the dose-dependent increased inflammatory gene expression or recruitment of inflammatory cells caused by adenoviral vectors when planning pre-clinical and/or clinical trials.

These studies highlight the importance of using high quality, well characterized viral vectors. Errors in the titration of these vectors and mistakes in the calculation of the amount of vectors administered will have serious, deleterious consequences for long term therapeutic transgene expression in the brain. Adenoviral vectors are very effective as therapeutic vehicles for gene therapy into the brain, but only at the right dose.

c. Adaptive Immune Responses Against Adenoviruses Injected Into The Brain: Calling in Reinforcements

As a result of the compartmentalization of the brain immune system, careful injection into the brain of non-replicating viral vectors at doses below the established immunological threshold provides long term therapeutic transgene expression and achieves therapeutically effective transgene expression in experimental models of neurological disorders. However, if the viral vectors escape to the peripheral organs or the lymphatic drainage, a systemic adaptive anti-adenoviral immune response mediates an almost complete elimination of transgene expression from the brain. T cells are the main cells responsible for eliminating transgene expression from the brain with very high efficiency. T cells are able to recognize as little as 1×103 iu of vector injected into the brain, an equivalent of 1000 transduced cells.[Barcia et al., 2006a]

If animals are injected with adenovirus intracranially and then immunized systemically against adenovirus within 30−60 days, transgene expression in the brain will be reduced by more 50% (Fig. 1). In studies by Barcia et al., our group demonstrated that an adaptive immune response was able to eliminate transgene expression from as little as 1000 infectious units injected into the brain.[Barcia et al., 2006a] For these experiments, a dose escalation of adenovirus was injected into the brain of naïve animals, followed by a systemic immunization against adenovirus. The resultant systemic immune response was able to eliminate transgene expression at doses from 107 to as low as 103 infectious units injected into the brain. The high efficiency by which the adaptive immune system eliminates transgene expression from the brain is highlighted by the detection and elimination of as little as 1000 infected cells in the brain.

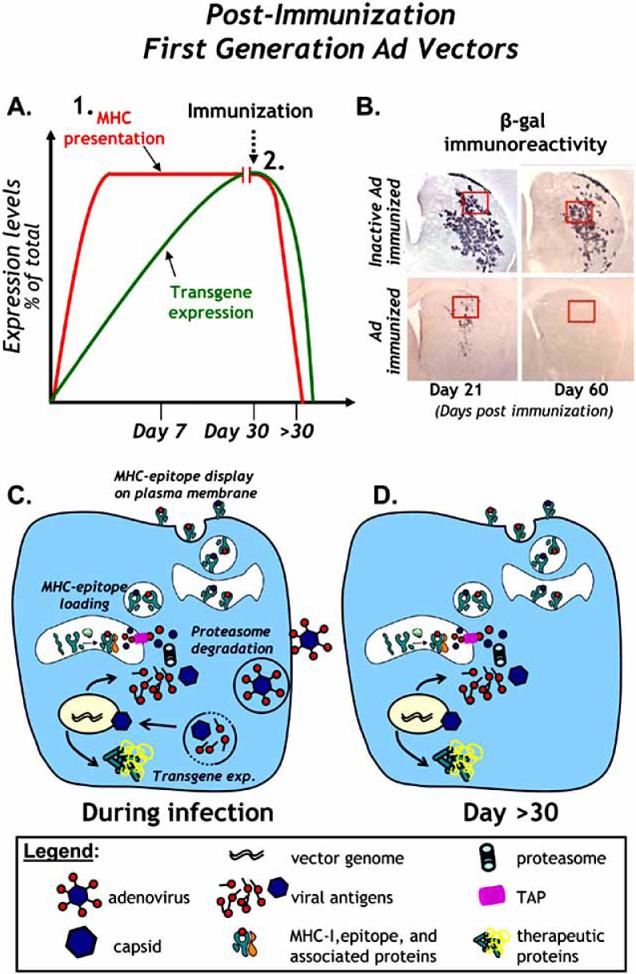

Fig. (1). Anti-adenoviral immune responses completely eliminate transgene expression from first generation adenoviral vectors.

A. The levels of transgene expression and MHC presentation of viral epitopes in animals injected with a first generation adenoviral vector into the CNS are illustrated. MHC-I presentation of viral epitopes peaks earlier due to intracellular degredation and presentation of capsid derived epitopes. Transgene expression (and consequent MHC antigen presentation) are completely abrogated following systemic immunization with adenovirus. B. Immunoreactivity for β-galactosidase illustrates the effects of a systemic immune response against adenovirus on transgene expression from first generation adenoviral vectors in the brain of rats immunized against inactivated adenovirus (top panels) or adenovirus (bottom panels). Short term (21 days post immunization, left panels) and medium term (60 days post immunization, right panels) expression of β-gal is shown. Note the sharp reduction of β-gal immunoreactivity in immunized animals compared to controls animals immunized with inactivated adenovirus. Sixty days later, transgene expression is completely eliminated in immunized animals while transgene expression is sustained in control immunized animals. C. A schematic of first generation vector infection, uncoating, nuclear transduction, production of transgene and presentation of viral antigenic epitopes on MHC-I is shown shortly after and during vector infection. D. A schematic of the same cells is shown >30 days later. Note the continued expression of viral proteins from the first generation adenoviral vector genomes and their presentation by MHC molecules on the cell surface.

Further experiments by Barcia et al[Barcia et al., 2006b], and Zirger et al. (in preparation), have shown that immune mediated elimination of transgene expression from the brain is dependant on the presence of CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells. We have also shown that the elimination of transgene expression was independent of the promoter used to drive transgene expression; whether viral, housekeeping, or cell type specific promoters are used to drive transgene expression, the immune system is able to eliminate transgene expression from all of these promoters[Barcia et al., 2006a].

d. High Capacity, Helper Dependent Adenoviruses. A Radical Makeover

The adverse immune responses would appear to mount an insurmountable block to stable, sustained, therapeutic gene therapy. Having identified the immune challenges, and in order to overcome these obstacles a new generation of viral vectors, known as high capacity, helper dependent adenoviruses (HC-Ad) have been recently developed to evade detection the immune system. These allow the insertion of up to 30 − 34 Kb of transgenic sequences but most importantly, the genomes of these vectors do not encode any viral proteins. Therefore, the HC-Ad genomes do not produce any adenoviral proteins in situ that could be recognized as antigenic epitopes by the immune system (Fig. 2). A series of papers by Thomas et al., [Thomas et al., 2000] Thomas et al., [Thomas et al., 2001a] Xiong et al,[Xiong et al., 2006] Barcia et al, (Molecular Therapy, In Press), O'Neal et al., [O'Neal et al., 2000] Mian et al., [Mian et al., 2005] Parks et al., [Parks et al., 1999] Maione et al., [Maione et al., 2001] and others have now demonstrated that transgene expression from these viruses remained stable, and was shown to persist for up to one year (Fig. 2B) Barcia et al, (Molecular Therapy, In Press), even in the presence of pre-existing immune response against adenovirus. Therefore, these vectors could be used even in human patients that have been pre-exposed to adenovirus before being subjected to gene therapy, as would be the case in the vast majority of human patients undergoing an experimental gene therapy using an adenoviral gene delivery system[Thomas et al., 2000; Thomas et al., 2001a; Xiong et al., 2006].

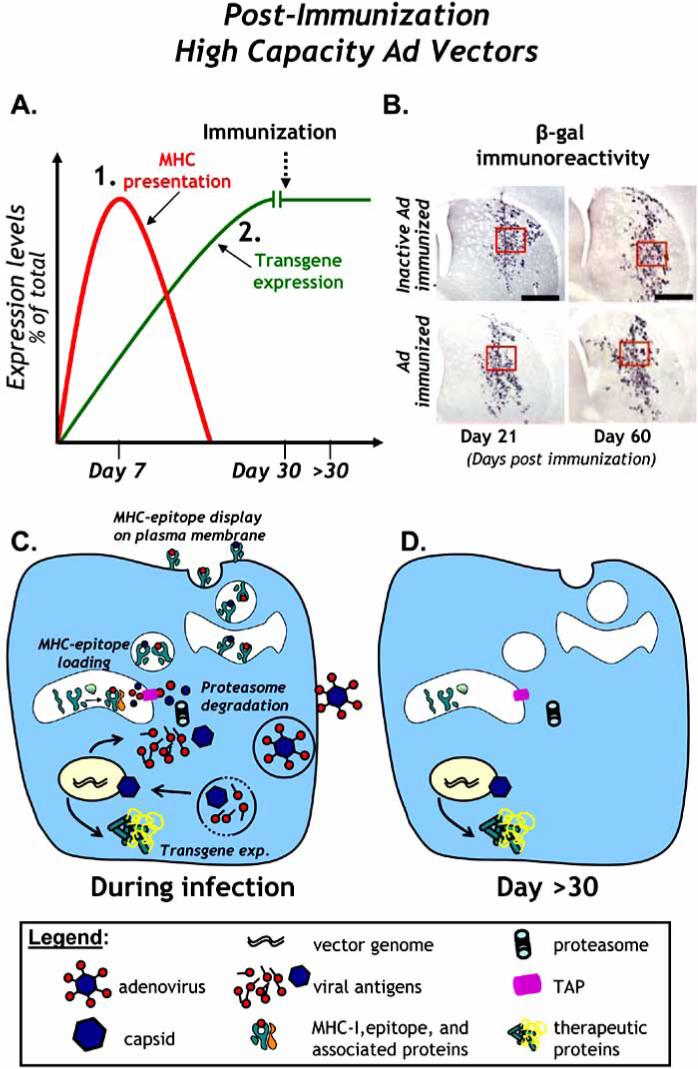

Fig. (2). Anti-adenoviral immune responses are incapable of eliminating transgene expression from HC-Ad vectors.

A. The levels of transgene expression and MHC presentation of viral epitopes in animals injected with a HC-Ad vector into the CNS are illustrated. MHC presentation of viral protein is short-term because only capsid derived epitopes can be presented during capsid degredation. Transgene expression in the brain is sustained, even after systemic immunization against adenovirus. B. Immunoreactivity for β-galactosidase illustrates the failure of a systemic immune response against adenovirus to eliminate transgene expression from HC-Ad vectors in the brain of rats immunized against adenovirus (top panels) or saline alone (bottom panels). Short term (21 days post immunization, left panels) and medium-long term (60 days post immunization, right panels) expression of β-gal is shown. Note the sustained expression of β-gal in both Ad-immunized animals and controls animals immunized with saline alone at 14 and 60 days immunization. C. A schematic of HC-Ad vector infection, uncoating, nuclear transduction, production of transgene and presentation of viral antigenic epitopes on MHC-I is shown after vector infection. D. A schematic of the same cells is shown >30 days later. Note the absence of expression of viral proteins from the HC-Ad vector and the lack of presentation of viral epitopes by MHC molecules on the cell surface.

Before HC-Ad vectors infect their target cells in the brain, the viral capsid of these vectors could, of course, be neutralized by anti-adenovirus antibodies. However, the adaptive arm of the immune system, the T cells, would have a very short period of time during which they can recognize cells that have been infected with HC-Ad vectors. Capsid proteins could be transiently presented on MHC Class1 molecules. However, such proteins would only be provided by the capsid directly administered, because the genome of these vectors does not encode for any viral proteins. Once these input virion proteins from the viral capsid have been metabolized, the HC-Ad vector effectively becomes immune to the antiviral T cells. Once the genome of these viruses has reached the nucleus, HC-Ad vectors are completely immune to the adaptive arm of the immune system (Fig. 2D). Therefore, further engineering of these vectors shows that adenoviruses are effective vehicles for long term therapeutic transgene expression in the brain.

e. Administering Gene Therapy to Pre-Immunized Animals: A Clinically Relevant Paradigm

To mimic the anti-adenovirus immunization status of patients unrolled in clinical trials using an adenoviral vectors, Thomas et al. and Barcia et al. performed experiments to assess the longevity of transgene expression in animals that had been pre-immunized against adenoviral before intracranial delivery of Ad vectors[Thomas et al., 2001b] and (Barcia et al., In press). This experimental paradigm was used to assess intracranial transgene expression in the presence of a systemic anti-adenoviral immune response in rats for up to 60 days post intracranial delivery [Thomas et al., 2001b] and also in mice for up to one year after intracranial delivery (Barcia et al., In press) (Fig. 3). In both species intracranial transgene expression mediated by first generation adenoviral vectors was nearly abolished (mouse) or totally abolished (rats) within 60 days in animals immunized systemically compared to control, saline immunized animals (Fig 3B). As expected, HC-Ad elicited sustained intracranial transgene expression even in the presence of an ant-adenoviral immune response in both rats and mice. We detected high levels of HC-Ad mediated transgene expression in the brains of animals at the longest timepoint tested (i.e 60 days in rats and 365 days in mice) (Fig 3C). In fact the levels of HC-Ad mediated transgene expression were indistinguishable between mice immunized with adenovirus or saline alone for all timepoints tested between 14 to 365 days (Barcia et al., In Press). These data further support implementing the HC-Ad vector platform into upcoming clinical trials for neurological disorders.

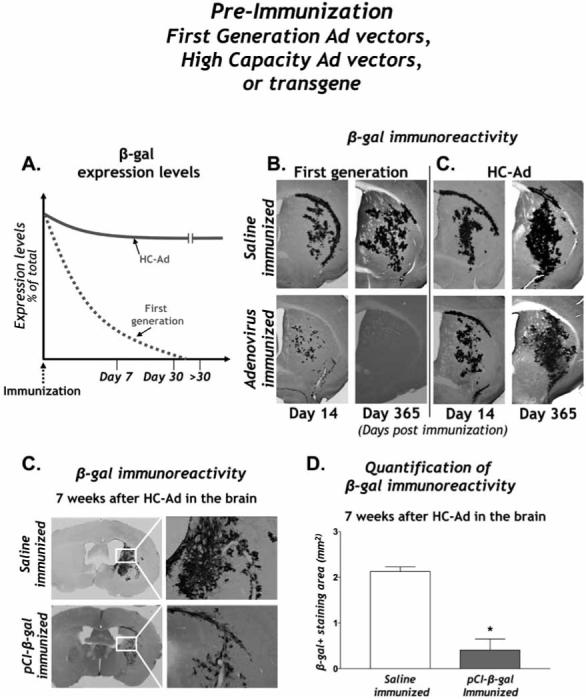

Fig. (3). Comparison of pre-existing responses against first generation adenovirus, high capacity adenovirus, and transgene.

A. The levels of intracranial transgene expression in the presence of a pre-existing systemic anti-adenovirus immune response are shown. Note the sharp reduction of transgene expression following intracranial delivery of first generation adenovirus compared to HC-Ad transgene expression. B. First generation adenovirus and C. HC-Ad mediated transgene expression in the mouse brain is visualized by β-gal immunoreactivity at 21 days and one year post intracranial vector delivery. Note the sustained expression of β-gal from both vectors in control immunized animals and persistence of expression in animals injected with HC-Ad even at one year post vector injection compared to the complete ablation of transgene expression in animals injected with first generation adenoviral vectors. C. β-gal immunoreactivity in the brain of animals pre-immunized with saline (top panels) or with β-gal (bottom panels) is shown seven weeks post intracranial vector delivery. Right panels depict high magnification images of immuoreactive area. D. Quantitative stereology of β-gal immunocytochemistry reveals a statistically significant decrease in β-gal immunoreactivity in animals pre-immunized with β-gal when compared to animals immunized with saline alone.

We also performed pre-immunization studies to examine the effects of a systemic immune response against the vector encoded transgene. To do so, Xiong et al.. [Xiong et al., 2007] immunized naïve mice with a systemic administration of a mammalian expression plasmid containing the transgene β-galactosidase or saline alone. Animals then received an intracranial administration of an HC-Ad vector encoding β-gal and the brains were analyzed for β-gal immunoreactivity seven weeks later (Fig. 3C). Quantitative stereology revealed a statistically significant decrease in β-gal immunoreactivity in animals pre-immunized against β-gal when compared to mice immunized with saline alone (Fig. 3D). These data and data from other groups[Molnar-Kimber et al., 1998; Favre et al., 2002; Lena et al., 2005; Di Domenico et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2006] suggest that transgene-specific immune responses must also be taken into consideration when planning and implementing a gene therapy clinical trial. Whether the mechanisms that reduce transgene expression in the brain and peripheral organs are the same remains to be determined.

f. Immune Responses Against AAV Vectors Injected into the Brain

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a small single-stranded DNA virus that was originally discovered as a contaminant in cell lines used to study adenovirus [Muzyczka et al., 2001]. Similar to HC-Ad, all the viral encoding genes have been removed from the recombinant AAV (rAAV) and replaced with a transgene and transcriptional elements inserted between two ITRs [Muzyczka et al., 2001]. Wild-type AAV is not associated with any known human disease and requires helper functions from Ad or other cytotoxic viruses in order to replicate and infect new host cells [Muzyczka et al., 2001]. Also, like Ad5, the majority of the human population has been exposed to the most common AAV serotype (AAV2) resulting in circulating neutralizing antibodies [Blacklow et al., 1968; Blacklow et al., 1971; Chirmule et al., 1999; Erles et al., 1999]. Immune responses to rAAV2 have been reported in the peripheral immune system, where competent DCs and lymph drainage exists[Zaiss et al., 2005; Mingozzi et al., 2007].

rAAV has been used extensively in the brain [Mandel et al., 2006] and is currently in several clinical trials for neurological disorders [Mandel et al., 2004; Kaplitt et al., 2007]. Due to the immune compartmentalization of the brain and lack of an adaptive immune response as discussed above[Matyszak et al., 1996; Stevenson et al., 1997b; Cartmell et al., 1999; Lowenstein, 2002], intra-parenchymal brain administration of rAAV has been thought to induce little immunogenicity especially when injected once in the parenchyma of naïve animals [Mandel et al., 1998; Lo et al., 1999; Mastakov et al., 2002; Peden et al., 2004].

As with adenovirus, transient, innate inflammatory responses to highly purified rAAV also occur when higher doses are administered into the naïve brain parenchyma [Reimsnider et al., 2007]. The discrepancy regarding the innate inflammatory responses between earlier reports from our lab [Mandel et al., 1998] and our recent data [Reimsnider et al., 2007] is most likely due to the increased titers of rAAV injected. Thus, although no formal study of a dose-dependant innate immune response to rAAV have been undertaken, there was little or no detectable innate immune response when injecting lower titers of rAAV2 vectors (2 × 108 particles [Mandel et al., 1998], 4 × 108 [Peden et al., 2004]) 4 weeks after intrastriatal transduction. However when injecting higher titers rAAV2 vectors (≈ 4 × 1010 particles) [Reimsnider et al., 2007] a significant transient GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) response was observed. Thus, the observation of an increased striatal inflammatory response to increasing titers of rAAV2 could be considered similar to the observation that intrastriatal injections of increasing titers of adenoviral vectors also leads to an innate immune response once a threshold Ad titer is reached [Thomas et al., 2001a].

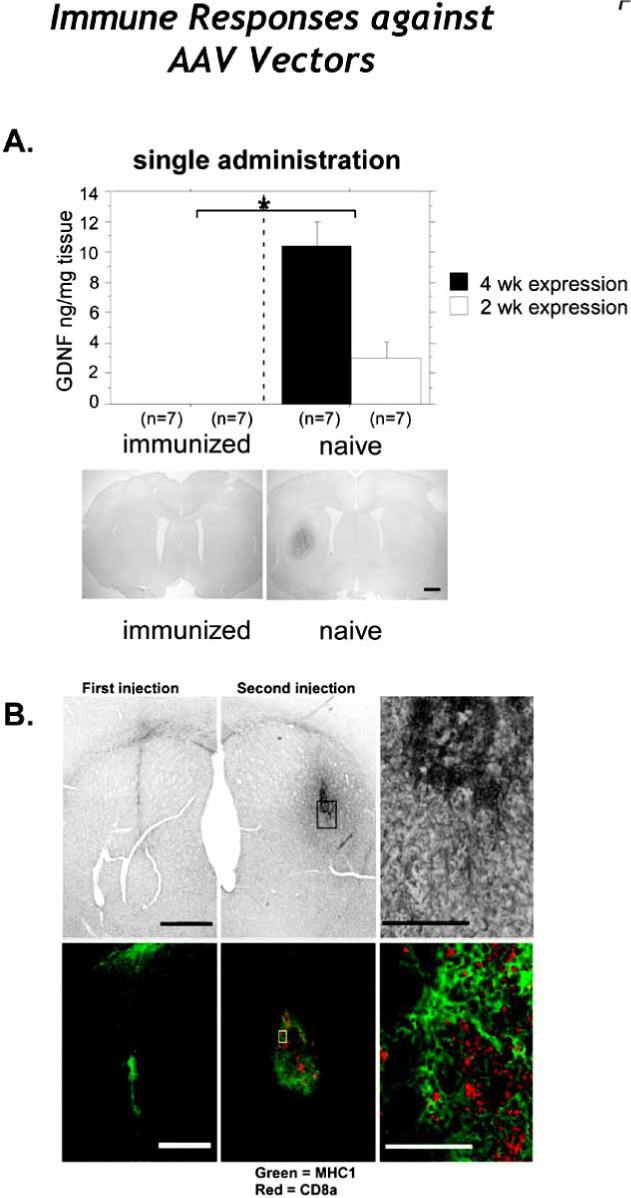

In addition to single injections of rAAV2 into naïve rats, re-administration of rAAV2 vectors in the opposite hemisphere either 2 or 4 weeks apart induces a significantly greater inflammatory response in the second injection site [Mastakov et al., 2002; Peden et al., 2004] (Fig. 4a). Mastakov et al. [Mastakov et al., 2002] also reported reduced expression of the rAAV2-mediated luciferase transgene in the second injection site whereas Peden et al. [Peden et al., 2004], did not observe reduced transgene expression when using human glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) as the transgene [Peden et al., 2004]. However, we have subsequently replicated the loss of rAAV2-mediated transgene expression in the second injection site when using GFP as the transgene (Peden and Mandel, unpublished observations).

Fig. (4). Pre-existing responses against AAV vectors.

A. Intrastriatal GDNF expression as determined by ELISA (top panels) and immunohistochemistry (bottom panels). Immunization with wt AAV2 completely blocked GDNF expression at both the 2- and 4-week time points following rAAV2-GDNF striatal transduction.as evidenced the striatum by both ELISA and ICC when compared to naïve animals. Injection of rAAV2 in the right striatum completely blocked GDNF expression when AAV2-GDNF was readministered in the left striatum (bottom left panel). The bottom right panels shows a representative section from a naive animal 4 weeks after rAAV2-GDNF injection in right striatum, with no further treatment. B. Striatal sections were immunostained with for MHC-I (green) and CD8α (red) in animals injected with rAAV. Note the increase of CD8α immunoreactivity in the brains of animals that received a second injection (middle panel) as compared to those animals only receiving a single injection (left panel). The right panel is a higher magnification image of the middle panel.

Upon first consideration, a significant rAAV-induced re-administration immune response in the brain is difficult to explain since no viral genes are expressed after rAAV transduction due to the lack of genes encoding viral proteins. However, rAAV2 vectors have been reported to uncoat slowly, thus potentially allowing processed capsid peptides to be presented via MHC-I [Lowenstein, 2004; Thomas et al., 2004; Herzog, 2007] (Fig. 2C). Antigen presentation of AAV2 capsid peptides as the etiology of an increased inflammatory response in the second injection site is supported by increased MHC-I expression that we observe in the second injection site after intrastriatal delivery of rAAV2 vectors [Peden et al., 2004](Fig. 4b). The other possibility besides the extended presentation of AAV2 capsid peptides is a transgene specific inflammatory response. However, when we re-administer a different serotype, rAAV5 expressing GFP in the second injection site, no enhanced inflammation or reduction of rAAV-transduced GFP+ neurons was observed (Reimsnider, Manfredsson and Mandel, unpublished observations). Further supporting the hypothesis of extended presentation of AAV2 capsid peptides , Mastakov et al. reported that transgene expression was unaffected following re-administration of rAAV2 three months after the first intrastriatal injection [Mastakov et al., 2002]. We have also recently replicated the phenomenon that a longer delay between rAAV2 administrations allows high levels of transgene expression following re-administration of the vector (Reimsnider, Manfredsson, and Mandel unpublished observations). Finally, we have shown that acute re-administration of rAAV5 vectors, which uncoat more rapidly than rAAV2 capsids, does not result in increased inflammation or transgene reduction in the second injection site.

All of the foregoing experiments were carried out in animals that were naïve to wt-AAV since wt-AAV does not ordinarily infect rodents. However, because a significant portion of the human population has been exposed to wt-AAV [Blacklow et al., 1968; Blacklow et al., 1971; Chirmule et al., 1999; Erles et al., 1999], it is important to study any potential immune response against rAAV in the CNS of pre-immunized animals. Thus, two studies demonstrated that intrastriatal rAAV2-mediated transduction was completely blocked by systemic pre-immunization against wt-AAV2 [Peden et al., 2004] or against rAAV2 [Sanftner et al., 2004]. In both studies, high levels of circulating anti-AAV2 neutralizing antibodies were observed and these antibodies were specific for AAV2 since rAAV5-mediated transduction was unaffected [Peden et al., 2004]. These studies clearly establish that circulating neutralizing antibodies can affect intracerebral rAAV-mediated transduction. Moreover, when rAAV2 pre-immunized rats underwent an rAAV2 re-administration paradigm, a qualitatively greater immune response was seen in the second injection site as compared to the second injection site in non-immunized rats [Peden et al., 2004]. These data suggest that the adaptive arm of the immune system can be primed by intracerebral rAAV2 administration. This consideration is especially important because memory T cell responses to AAV1, AAV2, and AAV8 have been demonstrated in healthy individuals[Mingozzi et al., 2007]. Moreover, as mentioned above, it has been proposed that parencyhmal inflammation can lead to the infiltration of the brain by dendritic cells that may be able to present antigen to naïve T cells [McMahon et al., 2005]. Therefore, although the naïve brain is relatively immunoprivileged, especially with regard to its incapacity to prime T cells, CD8+ T cells can be found in the brain in pre-immunized animals inoculated with intrastriatal rAAV2 [Peden et al., 2004]. Thus, utilizing careful in vitro assays to detect AAV capsid pre-exisiting CD8+ T cell responses to proteins, such as those described by Mingozzi et al. [Mingozzi et al., 2007] prior to rAAV administration, might be useful in rAAV clinical trials for neurological disorders. This may be especially important when using AAV vectors. Because of their smaller size they may be able to diffuse out of the brain, even following careful delivery into the brain parenchyma; this does not occur following the injection of the larger adenoviral vectors.

In a recent Phase I clinical trial for Parkinson's Disease using a 50μL injection of AAV2 vector expressing glutamic acid decarboxlyase (GAD) into the subthalamic nucleus, there was no change in the levels of pre-existing anti-AAV2 circulating antibodies and/or neutralizing at any of the time points tested following treatment (1, 3, 6, and 12 months) compared to baseline levels. The work published by Kaplitt and co-workers suggests that careful administration of small volumes of AAV2 into the brain did not induce a measurable systemic antibody immune response against AAV2. Moreover, neutralizing antibodies against the therapeutic protein were not detected for up to one year following administration of the viral vector[Kaplitt et al., 2007]. The existence of T cell responses, much more difficult to detect, but potentially more deleterious remain to be explored in gene therapy brain clinical trials. In a clinical trial for Canavan disease using 900μL of AAV2 expressing aspartocylase (ASPA) split amongst six injection sites, investigators found low to moderately high levels of neutralizing antibodies to AAV2 in 3 out of 10 patients compared to pre-gene therapy levels [McPhee et al., 2006]. The differences in the neutralizing antibody responses between these two clinical trials could be attributed to differences in intracerebral injection volumes, anatomical site of injection, and the underlying brain pathology. These issues remain to be monitored in future ongoing studies.

In summary, in contrast to Ad, there have been few studies of the immune response after rAAV administration in the brain. However, the studies that exist indicate that there can be rAAV-induced immune reactions especially when using high titer viruses [Reimsnider et al., 2007]. The existence of a dose threshold above which inflammation is caused indicates the need to carefully monitor the dose and purity of the vector to keep within safe, non-toxic parameters. Thus, it is clear that more careful analysis of rAAV-mediated immune responses in the brain, similar to the studies that have been carried out with Ad, should be undertaken.

4. WHAT CAUSES LOSS OF TRANSGENE EXPRESSION? TO BE KILLED, SILENCED, OR COMMIT SUICIDE, THE ULTIMATE EXISTENTIAL QUESTION

While the case has clearly been made that the adaptive immune response is able to eliminate transgene expression from the brain, the mechanisms by which transgene expression is eliminated is not yet understood. Moreover, the consequences or “the fate” of the cell infected by the viral vector has yet to be definitely elucidated. In theory, two main possibilities could account for the loss of transgene expression. On the one hand, T cells, through the secretion of the effector molecules like IFNγ, could selectively turn off or silence transgene expression from transduced cells of the CNS while maintaining the presence of the vector genome. Alternatively, T cells could be able to eliminate transgene expression by killing transduced cells by cytotoxic pathways. The consequences of the particular mechanism of clearance of virally transfused cells are of paramount important. If T cells are able to silence expression from the viral genome, no anatomical damage is being done. Moreover, it could be possible to restart transgene expression from the quiescent vector genome. However, if cytotoxic T cells eliminate transgene expression by killing transduced cells, the consequences to gene therapy clinical trials would be more severe. So far, work done in various laboratories has been inconclusive on this issue.

Sorting out whether the immune system can kill brain cells directly has been difficult to determine beyond reasonable doubt. From a teleological point of view if would clearly be preferably to protect brain cells from immune-mediated cell death. However, this preconception clearly cannot influence the outcome of neuroimmune interactions. If CTLs could kill brain cells these would need to express MHC-I. Although emphasis has been placed on determining whether brain cells, astrocytes and neurons, express MHC-I, information on whether the full complement of the intracellular machinery needed to load antigenic peptide onto MHC-I is present in brain cells is not known. Thus, even if expression of MHC-I has been shown in some cases, strong evidence that MHC-I on neurons can truly server to bind the TCR of CTLs remains to be uncovered. It is also highly likely that whether the immune system can eliminate brain cells will depend on the antigens expressed by brain cells, which virus they are being expressed from, and the nature of the immune response that was stimulated to detect infected cells in the brain. Dissecting these issues is part of important ongoing investigations by several laboratories.

Some of the limitations in detecting brain cell death relate to the number of infected cells in target brain areas. Because the number of infected cells is low (i.e. generally below 5% for the total amount of brain cells in any particular brain regions) loss of such relatively small percentage of brain cells be very difficult to detect experimentally. Added to this, the brain repairs itself rather effectively through astrocytosis, and dead brain cells are quickly phagocytosed by local microglial cells and possibly incoming macrophages, thereby keeping brain inflammation at a reasonable minimum.

For the long term success of clinically effective neurological gene therapy, the ultimate consequences of the mechanisms of elimination of transgene expression are of crucial importance. If the immune system turns off transgene expression through inhibitory transcriptional mechanisms, no permanent anatomical damage will ensue. However, if the immune system kills transduced cells, the underlying disease could worsen. Therefore, the detailed mechanisms by which the immune system abolishes transgene expression from transduced brain cells needs to be determined in order to develop alternative manners to escape, manipulate, or hide, from the immune system. A potential solution would be short-term immunosuppression while the viral capsid epitopes are displayed on MHC-I during vector uncoating [Herzog et al., 2001; Lowenstein, 2005; Mingozzi et al., 2007]. As discussed above (Figs. 1 and 2), the duration of viral capsid antigen presentation on MHC-I, and consequent necessary immunosuppression, would be determined by the half-life of the viral capsid proteins (i.e first generation Ads, HC-Ads or AAV vectors).

5. THE CELLULAR SUBSTRATE OF BRAIN IMMUNE RESPONSES: THE IMMUNOLOGICAL SYNAPSES

Recent advances in optical imaging and molecular methods allow to study immune reactions at the single cell level. Thus, the biology of immune responses can now be studied at level of single cell interactions in vivo, in addition to analysis of the function of large populations of immune cells studied using methods such as CTL and ELISPOT assays. Over the last ten years a structural rearrangement of proteins at the interfaces of interacting immune cells has been characterized as immunological synapses. Immunological synapses form between T cells and various types of antigen presenting cells, and consist of a reorganization of membrane proteins (i.e., intercellular adhesion molecules [e.g. ICAM-1], TCR), intracellular TCR downstream signaling tyrosine kinases, as well as cytoskeletal structures, and intracellular organelles of the secretory pathway of the T cells [Monks et al., 1998; Grakoui et al., 1999; Dustin et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2002; Huppa et al., 2003; Friedl et al., 2005; Huse et al., 2006; Cemerski et al., 2007]. The formation of immunological synapses is thought to represent the morphological expression of vectorial immune exchanges between T cells and antigen presenting cells.

A canonical structure, described as the mature immunological synapse has been described as consisting of the following arrangement: a peripheral supramolecular activation cluster (pSMAC), consists of a ring of adhesion molecules that anchor the membrane of the T cell to the membrane of the APC, while a central-SMAC (cSMAC), consists of a higher concentration of TCR and signaling molecules. Immunological synapses have been described for both CD4+ and CD8+T cells, and NK cells in contact with various types of APCs, e.g. dendritic cells, B cells, or target cells. Most studies on immunological synapses have studied the interactions between T and APCs in vitro, or the interaction of T cells with artificial bilayer membranes.

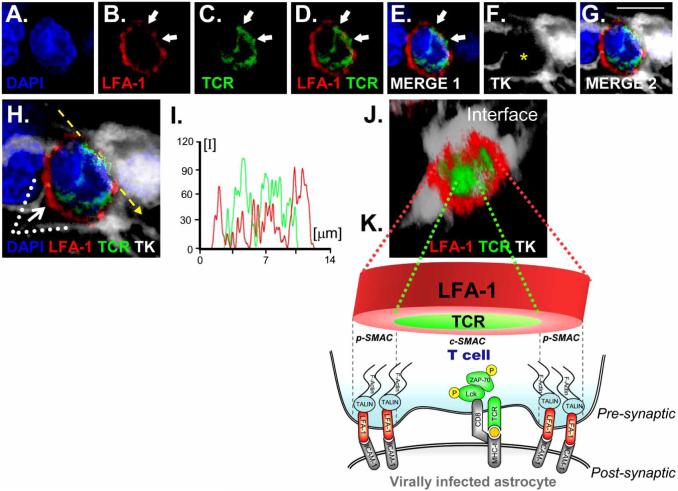

Most recently, the existence of mature type immunological synapses has also been described in the brain in vivo during an immune-mediated elimination of adenovirally infected cells from infected astrocytes. Anti-adenoviral CD8+ T cells infiltrate the brain and form Kupfer-type mature immunological synapses with astrocytes that express MHC-I[Barcia et al., 2006a; Barcia et al., 2006b]. Immunological synapses displayed the typical organization of TCR and LFA-1 into supramolecular activation clusters (SMACS), which constitute the hallmark of immunological synapses originally described by the group of Abraham Kupfer (Fig.5).

Fig. (5). SMAC formation at immunological synapses in vivo, between T cells and infected astrocytes in the brain.

Upper panels illustrate confocal images of: DAPI (blue), LFA-1 (red), TCR (green), and the virally infected cell (TK; in white) (Fig. 1A-F). Scale bars=15 μm. The yellow asterisk in F indicates the location of the T cell. Low (G) and high (H) magnifications of the synapse are illustrated. 3D reconstructed images (J) illustrate the characteristic structure of the p-SMAC (outer LFA-1 ring) and c-SMAC (inner TCR cluster) of the immunological synapse. The image shown in J was rotated so that the plane of the interface of the immunological synapse (broken arrow in 1H) could be observed from above (white arrow in H shows the angle of vision of the 3D reconstruction in J). I illustrates the intensity of fluorescence measured at the interface (yellow line in H) of the immunological synapse. The graph shows the relative intensity values of fluorescence of LFA-1 (in red) and TCR (in green), showing the expected distribution with more intense LFA-1 staining towards the outside p-SMAC, and stronger TCR in the c-SMAC. K is diagrammatic view of a T-cell contacting an infected astrocyte illustrating the localization of molecules involved in the immunological synapse as well as polarized phosphorylated tyrosine kinases. LFA-1 transduces signals to the cytoskeleton through talin, and binds to ICAM-1 on the target cells.

The characteristics of our experimental model to characterize the cellular and molecular biology of adaptive immune responses against a non-replicating adenoviral gene therapy vector are the following. A first generation adenoviral vector was used to target astrocytes in the rat brain. This virus is replication-defective and thus unable to directly kill infected cells. As the parenchymal CNS infection itself does not induce significant inflammation nor a systemic anti-adenoviral immune response, systemic anti-adenoviral immunization to target the infected brain cells was induced by immunizing systemically with a different Ad vector injected subcutaneously. Systemic anti-adenoviral immunization triggered a systemic anti-adenoviral immune response, which led to brain infiltration of antiviral T cells and brain inflammation. Brain inflammation consisted mainly of an infiltration of the brain parenchyma with CD8 T cells and macrophages that homed in to the area occupied by infected astrocytes, and a perivascular infiltration of CD4 T cells.

The systemic anti-adenoviral immune response resulted in a significant reduction in the number of transduced brain astrocytes; this was accompanied by a reduction in the number of viral genome copy numbers present in the CNS, as would be expected if the lymphocytes were killing infected brain cells. The presence of CD8 T cells within the brain parenchyma suggested the operation of direct cytotoxicity, though no direct evidence for apoptotic astrocytes was obtained. Nevertheless, macrophages containing remains of infected astrocytes were found, indicating that infected cells had been cleared by brain monocyte-derived cells.

We thus proposed that immunological synapses represent the microanatomical substrate underlying CD8 T cell effector functions in the CNS (Fig. 6) and mediate the clearing of infected astrocytes by CD8 T cells. The importance of these studies is the demonstration that immunological synapse do form indeed in vivo in the brain during the clearing of virally infected astrocytes by the adaptive immune response. Their in vivo description in the context of an anti-viral immune response highlights their physiological role as the structure underlying neuroimmune interactions in vivo. These data further demonstrate that CD8+ T cells are able to directly interact with and eliminate infected astrocytes. If we consider immunological synapses as the substrate of T cell interactions with target cells in vivo, we can then use them to help us to dissect whether effector mechanisms are exerted through direct or indirect interactions. For example, the visualization of CD8+ T cells directly interacting with astrocytes to be cleared argues for a direct cytotoxic mechanism underlying the elimination of infected astrocytes; however, if we would only be able to visualize CD8+ T cells interacting with macrophages, we would have to postulate an indirect mechanism to account for the clearing of virally infected astrocytes. The study of the in vivo cell biology of effector immune mechanisms in the brain will allow us to dissect the detailed cellular pathways through which the immune system achieves its functions in vivo.

6. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The communication between CD8+T cells and resident cells of the CNS is highly sophisticated; yet our understanding of these complex in vivo interactions is only now emerging. Major limitations reside in the unique interactions and crosstalk between CNS cells amongst themselves, their fully differentiated state in mature individuals, and their complex three dimensional structures. The network of the brain makes it difficult to extrapolate results obtained from in vitro studies using primary cultures from neonatal tissue exposed to lymphocytes removed from whole animals, to events occuring in vivo. Although glial cells and neurons are capable of expressing MHC-I in vitro and thus acting as targets for in vitro stimulated CD8+ T cells, the mode of CD8+ T cell function in vivo has largely been deducted from indirect evidence, such as viral clearance, loss of detection of viral genomes, demyelination or tissue atrophy. How T cells eliminate viral infections from the CNS, and whether they could do so by directly contacting infected brain cells, or indirectly through interactions with brain microglial cells remains contested.

How lymphocytes clear viral brain infections, and brain cells transduced with viral vectors is likely to depend crucially on the individual virus and/or vector, its capacity to remain latent or persistent in brain cells, the exact nature of the infected cell type, the anatomical region infected, and the level of T cell activation. Additional characteristics, such as sex and age are also likely to be crucial determinants of the outcome of T cell mediated clearing of viral infections.

Teleologically, non-cytolytic clearing of non-dividing infected brain cells may be preferable to killing of postmitotic neurons, the alternative needs to be thoroughly examined. Direct contact or even proximity of Class I expressing cells and CD8+ T cells in situ has only been demonstrated in isolated reports. Similarly, the notion of curative rather than cytolytic virus clearance should be regarded critically, as demonstration of apoptotic or dead CNS resident cells in situ, especially if the numbers are sparse are technically challenging.

The technical challenge of determining cell death in vivo is substantial and crucial for our understanding of the consequences for gene therapy of immune-mediated responses to vector-transduced brain cells. Immune-mediated killing cell assays rely on removing T cells from the target organ and exposing them to artificial target cells in vitro. While such studies have demonstrated the capacity of T cells isolated from infected brains to kill pre-selected target cells, this comes short of demonstrating that these cells indeed kill brain cells in vivo. In vivo killing assays using CFSE labeled target cells have been developed, yet their application to CNS tissue has not yet been achieved. While such assays come closer to demonstrating that T cells can kill within the animal, whether T cells can directly kill brain target cells in situ, remains to be explored further. It is likely that novel methods will need to be developed to examine directly the capacity of T cells to do so.

Finally, it is likely that a combination of novel microanatomical imaging techniques will encourage new analyses of T cell activity in the CNS. We believe that a novel examination of the interactions of T cells with target brain cells at the individual cellular level in vivo, will allow new perspectives on T cell function in the CNS. New morpho-functional approaches, such as the study of immunological synaptic function in vivo utilizing confocal microscopy, or direct in vivo analysis of T cell – CNS cell interactions using two photon microscopical approaches will usher in further understandings of T cell function in the brain in vivo, either during the beneficial clearing of viral infections, immunopathology in response to brain infection, or autoimmune attack.

For the last ten years we and other groups have shown that immune responses against adenoviral vectors can be deleterious for brain structure in function, eventually leading to the loss of transgene expression and brain cell death. The evidence suggests that the T cell response that can identify infected cells in the brain and either eliminate them physically or functionally. Further evidence has accumulated in at least two species that T cells can actually physically eliminate vector-transduced brain cells. Should these data be correct, the logical conclusions would be to avoid the use of such vectors in clinical gene therapy trials. However, questions remain, since it is difficult to compare immune responses across species, especially, when the overall magnitude of the immune response may be what determines the clinical outcome. Further complications arise from trying to gauge the strength of the immune response in humans, who may have been exposed to wild type adenovirus decades before being exposed to gene therapy. While the threat of a deleterious immune response remains, it is almost impossible to model such responses in experimental animal species towards establishing credible expectations when translating these experiments into humans.

Two options remain. Either experiments are performed in humans never exposed to adenovirus before, or, in whom such a response cannot be detected, or novel vectors are developed specifically for clinical trials use. The first option will retain the threat of an immune response that, at a minimum, may eliminate therapeutic transgene expression, and, at a maximum compromise normal brain tissue, thereby worsening the underlying disease. The second option, is more complicated, but a number of novel viral vectors exist with a much more favorable immune profile. Within the area of adenoviral vectors, the vector structure of the HC-Adv is such that, following established gene transfer, no antigenic viral epitopes remain within infected cells; barred the development of an immune response against the therapeutic transgene, these vectors are effectively invisible to the immune system. Thus, HC-Ad are likely to represent a major step towards the implementation of gene therapy for neurological diseases, especially those therapeutic approaches requiring long term, stable, sustained expression of one or more therapeutic transgenes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders & Stroke (NIH/NINDS) Grant 1R01 NS44556.01, Minority Supplement NS445561.01; 1R21-NSO54143.01; 1UO1 NS05 2465.01, 1 RO3 TW006273-01 to M.G.C.; NIH/NINDS Grants 1 RO1 NS 054193.01; RO1 NS 42893.01, U54 NS045309-01 and 1R21 NS047298-01 to P.R.L.. The Bram and Elaine Goldsmith and the Medallions Group Endowed Chairs in Gene Therapeutics to PRL and MGC, respectively, The Linda Tallen & David Paul Kane Foundation Annual Fellowship and the Board of Governors at CSMC. We thank S. Melmed, R. Katzman, and D. Meyer for their support and academic leadership. The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Ali S, King GD, Curtin JF, Candolfi M, Xiong W, Liu C, Puntel M, Cheng Q, Prieto J, Ribas A, Kupiec-Weglinski J, van Rooijen N, Lassmann H, Lowenstein PR, Castro MG. Combined immunostimulation and conditional cytotoxic gene therapy provide long-term survival in a large glioma model. Cancer Res. 2005;65(16):7194–7204. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcia C, Gerdes C, Xiong W, Thomas CE, Liu C, Kroeger KM, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Immunological thresholds in neurological gene therapy: highly efficient elimination of transduced cells may be related to the specific formation of immunological synapses between T cells and virus-infected brain cells. Neuron Glial. Biology. 2006a;2(4):309–327. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X07000579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcia C, Thomas CE, Curtin JF, King GD, Wawrowsky K, Candolfi M, Xiong WD, Liu C, Kroeger K, Boyer O, Kupiec-Weglinski J, Klatzmann D, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. In vivo mature immunological synapses forming SMACs mediate clearance of virally infected astrocytes from the brain. J. Exp. Med. 2006b;203(9):2095–2107. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechmann I, Galea I, Perry VH. What is the blood-brain barrier (not)? Trends Immunol. 2007;28(1):5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacklow NR, Hoggan MD, Rowe WP. Serologic evidence for human infection with adenovirus-associated viruses. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1968;40(2):319–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacklow NR, Hoggan MD, Sereno MS, Brandt CD, Kim HW, Parrott RH, Chanock RM. A seroepidemiologic study of adenovirus-associated virus infection in infants and children. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1971;94(4):359–366. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartmell T, Southgate T, Rees GS, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR, Luheshi GN. Interleukin-1 mediates a rapid inflammatory response after injection of adenoviral vectors into the brain. J. Neurosci. 1999;19(4):1517–1523. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01517.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caux C, Ait-Yahia S, Chemin K, de Bouteiller O, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Homey B, Massacrier C, Vanbervliet B, Zlotnik A, Vicari A. Dendritic cell biology and regulation of dendritic cell trafficking by chemokines. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 2000;22(4):345–369. doi: 10.1007/s002810000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cemerski S, Das J, Locasale J, Arnold P, Giurisato E, Markiewicz MA, Fremont D, Allen PM, Chakraborty AK, Shaw AS. The stimulatory potency of T cell antigens is influenced by the formation of the immunological synapse. Immunity. 2007;26(3):345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiocca EA, Abbed KM, Tatter S, Louis DN, Hochberg FH, Barker F, Kracher J, Grossman SA, Fisher JD, Carson K, Rosenblum M, Mikkelsen T, Olson J, Markert JM, Rosenfeld S, Nabors LB, Brem S, Phuphanich S, Freeman S, Kaplan RS, Zwiebel J. A Phase I open-label, dose-escalation, multi-institutional trial of injection with an E1B-attenuated adenovirus, ONYX-015, into the peritumoral region of recurrent malignant gliomas, in the adjuvant setting. Mol. Ther. 2004;10(5):958–966. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirmule N, Propert K, Magosin S, Qian Y, Qian R, Wilson J. Immune responses to adenovirus and adeno-associated virus in humans. Gene Ther. 1999;6(0969−7128):1574–1583. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserr HF, Knopf PM. Cervical lymphatics, the blood-brain barrier and the immunoreactivity of the brain: a new view. Immunol. Today. 1992;13(12):507–512. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey RA, Morrissey G, Cowsill CM, Stone D, Bolognani F, Dodd NJ, Southgate TD, Klatzmann D, Lassmann H, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Chronic brain inflammation and persistent herpes simplex virus 1 thymidine kinase expression in survivors of syngeneic glioma treated by adenovirus-mediated gene therapy: implications for clinical trials. Nat. Med. 1999;5(11):1256–1263. doi: 10.1038/15207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Domenico C, Di Napoli D, Gonzalez YRE, Lombardo A, Naldini L, Di Natale P. Limited transgene immune response and long-term expression of human alpha-L-iduronidase in young adult mice with mucopolysaccharidosis type I by liver-directed gene therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006;17(11):1112–1121. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- During MJ, Kaplitt MG, Stern MB, Eidelberg D. Subthalamic GAD gene transfer in Parkinson disease patients who are candidates for deep brain stimulation. Hum. Gene Ther. 2001;12(12):1589–1591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustin ML, Cooper JA. The immunological synapse and the actin cytoskeleton: molecular hardware for T cell signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1(1):23–29. doi: 10.1038/76877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksdotter Jonhagen, M., Nordberg A, Amberla K, Backman L, Ebendal T, Meyerson B, Olson L, Seiger, Shigeta M, Theodorsson E, Viitanen M, Winblad B, Wahlund LO. Intracerebroventricular infusion of nerve growth factor in three patients with Alzheimer's disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 1998;9(5):246–257. doi: 10.1159/000017069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erles K, Sebokova P, Schlehofer JR. Update on the prevalence of serum antibodies (IgG and IgM) to adeno- associated virus (AAV). J. Med. Virol. 1999;59(0146−6615):406–411. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199911)59:3<406::aid-jmv22>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre D, Blouin V, Provost N, Spisek R, Porrot F, Bohl D, Marme F, Cherel Y, Salvetti A, Hurtrel B, Heard JM, Riviere Y, Moullier P. Lack of an immune response against the tetracycline-dependent transactivator correlates with long-term doxycycline-regulated transgene expression in nonhuman primates after intramuscular injection of recombinant adeno-associated virus. J. Virol. 2002;76(22):11605–11611. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11605-11611.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, den Boer AT, Gunzer M. Tuning immune responses: diversity and adaptation of the immunological synapse. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5(7):532–545. doi: 10.1038/nri1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, Allen PM, Dustin ML. The immunological synapse: a molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285(5425):221–227. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog RW. Immune responses to AAV capsid: are mice not humans after all? Mol. Ther. 2007;15(4):649–650. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog RW, Mount JD, Arruda VR, High KA, Lothrop CD., Jr. Muscle-directed gene transfer and transient immune suppression result in sustained partial correction of canine hemophilia B caused by a null mutation. Mol. Ther. 2001;4(3):192–200. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppa JB, Davis MM. T-cell-antigen recognition and the immunological synapse. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3(12):973–983. doi: 10.1038/nri1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse M, Lillemeier BF, Kuhns MS, Chen DS, Davis MM. T cells use two directionally distinct pathways for cytokine secretion. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:247–255. doi: 10.1038/ni1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immonen A, Vapalahti M, Tyynela K, Hurskainen H, Sandmair A, Vanninen R, Langford G, Murray N, Yla-Herttuala S. AdvHSV-tk gene therapy with intravenous ganciclovir improves survival in human malignant glioma: a randomised, controlled study. Mol. Ther. 2004;10(5):967–972. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplitt MG, Feigin A, Tang C, Fitzsimons HL, Mattis P, Lawlor PA, Bland RJ, Young D, Strybing K, Eidelberg D, During MJ. Safety and tolerability of gene therapy with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) borne GAD gene for Parkinson's disease: an open label, phase I trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9579):2097–2105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopf PM, Harling-Berg CJ, Cserr HF, Basu D, Sirulnick EJ, Nolan SC, Park JT, Keir G, Thompson EJ, Hickey WF. Antigen-dependent intrathecal antibody synthesis in the normal rat brain: tissue entry and local retention of antigen-specific B cells. J. Immunol. 1998;161(2):692–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Holdorf AD, Dustin ML, Chan AC, Allen PM, Shaw AS. T cell receptor signaling precedes immunological synapse formation. Science. 2002;295(5559):1539–1542. doi: 10.1126/science.1067710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lena AM, Giannetti P, Sporeno E, Ciliberto G, Savino R. Immune responses against tetracycline-dependent transactivators affect long-term expression of mouse erythropoietin delivered by a helper-dependent adenoviral vector. J. Gene Med. 2005;7(8):1086–1096. doi: 10.1002/jgm.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon B, Lopez-Bravo M, Ardavin C. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells formed at the infection site control the induction of protective T helper 1 responses against Leishmania. Immunity. 2007;26(4):519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Montalcini R. The nerve growth factor 35 years later. Science. 1987;237(4819):1154–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.3306916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo WD, Qu G, Sferra TJ, Clark R, Chen R, Johnson PR. Adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer to the brain: duration and modulation of expression. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999;10:201–213. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein PR. Dendritic cells and immune responses in the central nervous system. Trends Immunol. 2002;23(2):70. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein PR. Input virion proteins: cryptic targets of antivector immune responses in preimmunized subjects. Mole. Ther. 2004;9:771–774. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein PR. The case for immunosuppression in clinical gene transfer. Mol. Ther. 2005;12(2):185–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.06.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maione D, Rocca C. Della, Giannetti P, D'Arrigo R, Liberatoscioli L, Franlin LL, Sandig V, Ciliberto G, La Monica N, Savino R. An improved helper-dependent adenoviral vector allows persistent gene expression after intramuscular delivery and overcomes preexisting immunity to adenovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98(11):5986–5991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101122498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel RJ, Burger C. Clinical trials in neurological disorders using AAV vectors: promises and challenges. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2004;6(5):482–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel RJ, Manfredsson FP, Foust KD, Rising A, Reimsnider S, Nash K, Burger C. Recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors as therapeutic agents to treat neurological disorders. Mol. Ther. 2006;13(3):463–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel RJ, Rendahl KG, Spratt SK, Snyder RO, Cohen LK, Leff SE. Characterization of intrastriatal recombinant adeno-associated virus mediated gene transfer of human tyrosine hydroxylase and human GTP-cyclohydroxylase I in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:4271–4284. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-11-04271.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastakov MY, Baer K, Symes CW, Leichtlein CB, Kotin RM, During MJ. Immunological aspects of recombinant adeno-associated virus delivery to the mammalian brain. J. Virol. 2002;76(16):8446–8454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8446-8454.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyszak MK. Inflammation in the CNS: balance between immunological privilege and immune responses. Prog. Neurobiol. 1998;56(1):19–35. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyszak MK, Perry VH. The potential role of dendritic cells in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases in the central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1996;74(2):599–608. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon EJ, Bailey SL, Castenada CV, Waldner H, Miller SD. Epitope spreading initiates in the CNS in two mouse models of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Med. 2005;11(3):335–339. doi: 10.1038/nm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin PG. Distribution and phenotype of dendritic cells and resident tissue macrophages in the dura mater, leptomeninges, and choroid plexus of the rat brain as demonstrated in wholemount preparations. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999;405(4):553–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee SW, Janson CG, Li C, Samulski RJ, Camp AS, Francis J, Shera D, Lioutermann L, Feely M, Freese A, Leone P. Immune responses to AAV in a phase I study for Canavan disease. J. Gene Med. 2006;8(5):577–588. doi: 10.1002/jgm.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian A, Guenther M, Finegold M, Ng P, Rodgers J, Lee B. Toxicity and adaptive immune response to intracellular transgenes delivered by helper-dependent vs. first generation adenoviral vectors. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;84(3):278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingozzi F, Hasbrouck NC, Basner-Tschkarajan E, Edmonson SA, Hui DJ, Sabatino DE, Zhou S, Wright JF, Jiang H, Pierce GF, Arruda VR, High KA. Modulation of tolerance to the transgene product in a non-human primate model of AAV-mediated gene transfer to liver. Blood. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-080093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar-Kimber KL, Sterman DH, Chang M, Kang EH, ElBash M, Lanuti M, Elshami A, Gelfand K, Wilson JM, Kaiser LR, Albelda SM. Impact of preexisting and induced humoral and cellular immune responses in an adenovirus-based gene therapy phase I clinical trial for localized mesothelioma. Hum. Gene Ther. 1998;9(14):2121–2133. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.14-2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks CR, Freiberg BA, Kupfer H, Sciaky N, Kupfer A. Three-dimensional segregation of supramolecular activation clusters in T cells. Nature. 1998;395(6697):82–86. doi: 10.1038/25764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu S, Fujimoto K, Ikeguchi K, Shizuma N, Kawasaki K, Ono F, Shen Y, Wang L, Mizukami H, Kume A, Matsumura M, Nagatsu I, Urano F, Ichinose H, Nagatsu T, Terao K, Nakano I, Ozawa K. Behavioral recovery in a primate model of Parkinson's disease by triple transduction of striatal cells with adeno-associated viral vectors expressing dopamine-synthesizing enzymes. Hum. Gene Ther. 2002;13(3):345–354. doi: 10.1089/10430340252792486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzyczka N, Berns KI. Parvoiridae; The viruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Williams and Wilkins; Lippincott: 2001. pp. 2327–2360. [Google Scholar]

- O'Neal WK, Zhou H, Morral N, Langston C, Parks RJ, Graham FL, Kochanek S, Beaudet AL. Toxicity associated with repeated administration of first-generation adenovirus vectors does not occur with a helper-dependent vector. Mol. Med. 2000;6(3):179–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks R, Evelegh C, Graham F. Use of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors of alternative serotypes permits repeat vector administration. Gene Ther. 1999;6(9):1565–1573. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashenkov M, Teleshova N, Link H. Inflammation in the central nervous system: the role for dendritic cells. Brain Pathol. 2003;13(1):23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peden CS, Burger C, Muzyczka N, Mandel RJ. Circulating anti-wt-AAV2 Antibodies Inhibit rAAV2-, but not rAAV5-mediated Gene Transfer in the Brain. J. Virol. 2004;78:6344–6359. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6344-6359.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimsnider S, Manfredsson FP, Muzyczka N, Mandel RJ. Time Course of Transgene Expression After Intrastriatal Pseudotyped rAAV2/1, rAAV2/2, rAAV2/5, and rAAV2/8 Transduction in the Rat. Mol. Ther. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanftner LM, Suzuki BM, Doroudchi MM, Feng L, McClelland A, Forsayeth JR, Cunningham J. Striatal delivery of rAAV-hAADC to rats with preexisting immunity to AAV. Mol. Ther. 2004;9(3):403–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Wilcox DA, Fahs SA, Weiler H, Wells CW, Cooley BC, Desai D, Morateck PA, Gorski J, Montgomery RR. Factor VIII ectopically targeted to platelets is therapeutic in hemophilia A with high-titer inhibitory antibodies. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116(7):1974–1982. doi: 10.1172/JCI28416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson PG, Freeman S, Bangham CR, Hawke S. Virus dissemination through the brain parenchyma without immunologic control. J. Immunol. 1997a;159(4):1876–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson PG, Hawke S, Sloan DJ, Bangham CR. The immunogenicity of intracerebral virus infection depends on anatomical site. J. Virol. 1997b;71(1):145–151. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.145-151.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CE, Birkett D, Anozie I, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Acute direct adenoviral vector cytotoxicity and chronic, but not acute, inflammatory responses correlate with decreased vector-mediated transgene expression in the brain. Mol. Ther. 2001a;3(1):36–46. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CE, Schiedner G, Kochanek S, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Peripheral infection with adenovirus causes unexpected long-term brain inflammation in animals injected intracranially with first-generation, but not with high-capacity, adenovirus vectors: toward realistic long-term neurological gene therapy for chronic diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97(13):7482–7487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120474397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CE, Schiedner G, Kochanek S, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Preexisting antiadenoviral immunity is not a barrier to efficient and stable transduction of the brain, mediated by novel high-capacity adenovirus vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2001b;12(7):839–846. doi: 10.1089/104303401750148829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CE, Storm TA, Huang Z, Kay MA. Rapid uncoating of vector genomes is the key to efficient liver transduction with pseudotyped adeno-associated virus vectors. J. Virol. 2004;78(6):3110–3122. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.3110-3122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuszynski MH, Thal L, Pay M, Salmon DP, Bakay HSU,R, Patel P, Blesch A, Vahlsing HL, Ho G, Tong G, Potkin SG, Fallon J, Hansen L, Mufson EJ, Kordower JH, Gall C, Conner J. A phase 1 clinical trial of nerve growth factor gene therapy for Alzheimer disease. Nat. Med. 2005;11(5):551–555. doi: 10.1038/nm1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong LF, Goodhead L, Prat C, Mitrophanous KA, Kingsman SM, Mazarakis ND. Lentivirus-mediated gene transfer to the central nervous system: therapeutic and research applications. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W, Goverdhana S, Sciascia SA, Candolfi M, Zirger JM, Barcia C, Curtin JF, King GD, Jaita G, Liu C, Kroeger K, Agadjanian H, Medina-Kauwe L, Palmer D, Ng P, Lowenstein PR, Castro MG. Regulatable gutless adenovirus vectors sustain inducible transgene expression in the brain in the presence of an immune response against adenoviruses. J. Virol. 2006;80(1):27–37. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.27-37.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W, Puntel M, Mondkar S, Curtin JF, Candolfi M, Kroeger KM, Liu C, Larocque D, Palmer D, Ng P, Lowenstein PR, Castro MG. Immune responses against tetracycline-dependant transactivators do not affect long-term transgene expression delivered by a helper-dependant adenoviral vector (HC-Ad). Mol. Ther. 2007;15(Supplement 1):S96–S97. [Google Scholar]

- Zaiss AK, Muruve DA. Immune responses to adeno-associated virus vectors. Curr. Gene Ther. 2005;5(3):323–331. doi: 10.2174/1566523054065039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirger JM, Barcia C, Liu C, Puntel M, Mitchell N, Campbell I, Castro M, Lowenstein PR. Rapid upregulation of interferon-regulated and chemokine mRNAs upon injection of 108 international units, but not lower doses, of adenoviral vectors into the brain. J. Virol. 2006;80(11):5655–5659. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00166-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]